Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Giorgia Schena | -- | 2740 | 2022-04-29 17:33:05 | | | |

| 2 | Jessie Wu | -1 word(s) | 2739 | 2022-05-05 08:38:42 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Schena, G.; Caplan, M. Beta-3 Adrenergic Receptor. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22517 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Schena G, Caplan M. Beta-3 Adrenergic Receptor. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22517. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Schena, Giorgia, Michael Caplan. "Beta-3 Adrenergic Receptor" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22517 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Schena, G., & Caplan, M. (2022, April 29). Beta-3 Adrenergic Receptor. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22517

Schena, Giorgia and Michael Caplan. "Beta-3 Adrenergic Receptor." Encyclopedia. Web. 29 April, 2022.

Copy Citation

The beta-3 adrenergic receptor (β3-AR) is by far the least studied isotype of the beta-adrenergic sub-family. Despite its study being long hampered by the lack of suitable animal and cellular models and inter-species differences, a substantial body of literature on the subject has built up in the last three decades and the physiology of β3-AR is unraveling quickly. As will become evident in this work, β3-AR is emerging as an appealing target for novel pharmacological approaches in several clinical areas involving metabolic, cardiovascular, urinary, and ocular disease.

beta-3 adrenergic receptor

therapeutic target

gene

1. Gene and Protein

The gene encoding β3-AR has been identified in several species such as rat [1], mouse [2], bovine, sheep, goat [3], and dog [4]. In humans, the gene is localized on chromosome 8 and shares a 51% and 46% identity with β1- and β2-AR amino-acid sequences, respectively. This is mostly limited to the transmembrane domains and membrane-proximal regions of the intracellular loops, parts of the receptor respectively involved in ligand binding and G-protein interactions [5][6]. The mouse and human β3-AR are 81% identical, with the highest homology in the transmembrane domains (94%), and the lowest in the C-terminal tail and third intracellular loop. Consistently, their C-terminal regions differ in sequence and length, ranging from 6 (human) to 12 (mouse and rat) additional residues. β3-AR gene also contains introns. The number of exons/introns of the human and rodent genes differs and can be summarized as follows: the human β3-AR gene is composed of two exons and a single intron while in mouse, there are three exons and two introns [7]. In both species, exon 1 spans the 5′ untranslated region and the major part of the coding block; however, in humans, exon 2 only contains 19 bp of the coding region (last 6 aa of the C-terminus) and the 3‘ untranslated region; in mouse it contains 37 coding nucleotides and 31 bp of 3‘ untranslated region, the remainder of which is carried by exon 3 [8]. Despite intron presence, no spliced variants have been described for the human β3-AR gene, whereas two have been characterized in the mouse [8][9][10].

β3-AR gene encodes a single 408–amino acid residue–long peptide chain that, together with β1- and β2-AR, belongs to the G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) family characterized by seven transmembrane (TM) domains, with three intracellular and three extracellular loops. The N-terminal region of β3-AR is extracellular and glycosylated, whereas the C-terminus is intracellular. Unlike in β1- and β2-AR, it lacks sites for phosphorylation by protein kinase A (PKA) and β-adrenoceptor kinase (βARK) thereby making β3-AR relatively resistant to desensitization [6][11][12]. Among others, this feature contributed in making β3-AR an interesting therapeutic target that would potentially be suitable for chronic treatments. From a molecular point of view, desensitization of β3-AR might not be mediated by internalization/degradation of the receptor, as for β1-AR [13], but rather by downregulation of downstream components of the signaling pathway [14] or even mRNA regulation (reviewed in [12]). However, caution must be used when evaluating the data present in literature as results were not always consistent (reviewed in [12]). Transmembrane domains TM3, TM4, TM5, and TM6 are essential for ligand binding, whereas TM2 and TM7 are involved in Gαs activation [15]. The disulphide bond between extracellular loops 2 and 3 is also essential for ligand binding and activity of the receptor. The Cys361 residue in the fourth intracellular loop is palmitoylated. Palmitoylation has been shown to mediate adenylyl cyclase stimulation by the agonist bound receptor, possibly by promoting the insertion of several adjacent residues into the membrane and thus forming an additional intracellular loop, resulting in an active conformation for G-protein coupling [16].

2. β3-AR as Therapeutic Target

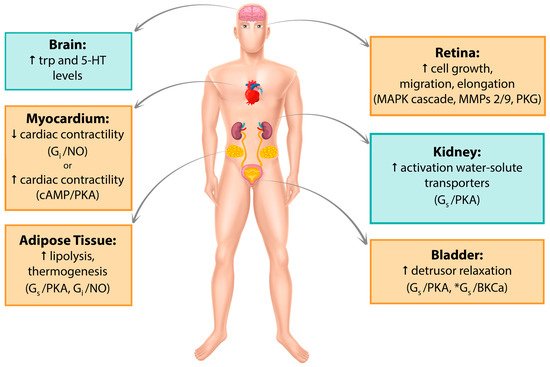

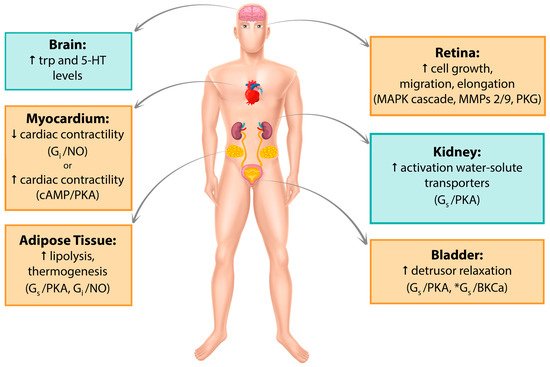

Since its discovery in the late 1980s, β3-AR has been detected in several human tissues such as myocardium, retina, myometrium, adipose tissue, gallbladder, brain, urinary bladder, and blood vessels. Its expression has been recorded both at the mRNA and protein levels, and its activation involves a variety of cellular pathways. A recent comprehensive quantitative analysis of the human transcriptome reported β3-AR expression to be far more restricted than previously hypothesized [17]; however, significant findings continue to be published. In the following sections, major tissues in which β3-AR expression has been studied so far, their associated signaling pathways and clinical implications in humans will be discussed. Figure 1 summarize the data reported in this section.

Figure 1. Graphic summary of β3-AR localization. Pathways that have been studied and reported in human tissue/cell lines are in yellow boxes. Pathways studied in mouse but not yet found in humans are in blue boxes. *Alternative cAMP-independent pathway. Trp, tryptophan; 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MMPs, metalloproteinases, PKG, protein kinase G; NO, nitric oxide; PKA, protein kinase A.

2.1. Urinary System

β3-AR has been localized in kidneys [18] and in the lower urinary tract [19] including ureters [20], urethra [21], prostate [22], and bladder [23] where it appears to be the predominant subtype [24] although this idea was recently challenged in a wide transcriptomics analysis across several human tissues [17].

The presence of an atypical β-receptor in human detrusor was first suggested in the 1970s [25][26] and was confirmed by evidence that muscle relaxation in pre-contracted samples could not be evoked by stimulation with β1- and β2-AR agonists but only with β3-AR agonists such as BRL37344A. Consistently, β3-AR antagonists SR58894A and L748337 both induced a rightward shift in the concentration–relaxation curve of isoproterenol-treated detrusor muscle preparations [27][28]. The presence of β3-AR transcript was first reported in human detrusor smooth muscle cells [28] while the protein was found later on in the detrusor and urothelium [23]. Determination of the relative abundance of each one of the three β-AR in the bladder muscle by quantitative analysis revealed β3-AR mRNA to be the most represented (97%) against 1.5% and 1.4% of β1- and β2-AR respectively [24]. However, the physiological significance of this result is limited as the tissue mRNA concentration does not necessarily correlate with the protein level.

As for the β3-AR signaling pathway in the bladder, several different and not always consistent hypotheses have been offered. Beta adrenergic signaling often relies on the cAMP/PKA pathway [29][30][31] and cAMP is a key player in smooth muscle relaxation, however the extent of its involvement in this process is still a matter of debate. Stimulation of non-contracted muscle strips with the β3-AR agonist FR165101 have been shown to induce a concentration dependent decrease in muscle basal tension and an increase in the cAMP levels. Furthermore, pre-incubation with adenylate cyclase inhibitor SQ22536 markedly suppressed both of these effects [32]. However, Maki et al. recently reported a milder effect of SQ22536 on human and pig pre-contracted detrusor strips treated with mirabegron supporting the hypothesis of a cAMP-independent mechanism, potentially via activation of myosin light chain phosphatase [33]. Along the same line, Frazier et al. previously showed that only Rp-cAMPS, among other PKA inhibitors had a small significant effect on isoproterenol responses against passive tension on non-contracted rat bladder strips, not supporting a major role for cAMP and/or PKA in β-AR-mediated bladder relaxation. They hypothesized an alternate signaling pathway involving a direct interaction of β-AR, or its linked Gs, with a different partner such as the large conductance Ca2+ activated K+ channel (BKCa) [34]. Both Uchida and Frazier showed that BKCa selective block had a negative effect on isoproterenol-stimulated pre-contracted rat bladder strips. In conclusion, these studies support a potential, and somewhat partial role, for cAMP/PKA pathway in β-adrenergic-mediated relaxation from passive tension of rat detrusor muscle; at the same time, they hypothesize a cAMP-independent mechanism involving BKCa channels in β-adrenergic modulation of smooth muscle active tone in the urinary bladder. Thus, the contribution of the two mechanisms seems to be dependent on the condition of the detrusor muscle. Additionally, D’Agostino et al. used electrical field stimulation (EFS) to show that β3-AR activation strikingly inhibits EFS-evoked contraction and acetylcholine (Ach) release from cholinergic nerves in a concentration-dependent manner in human detrusor bladder strips [35]. The fact that BKCa channel activation at prejunctional sites has a hyperpolarizing effect on parasympathetic nerve terminals [36] and that they are potentially involved in β3-AR signaling [32][34] might explain how β3-AR stimulation reduces neurotransmitter release. β3-AR modulation of ACh release is also supported by a recent immunohistochemistry study showing β3-AR expression on the detrusor cholinergic fibers in close proximity to sympathetic bundles innervating the human bladder. This arrangement is physiologically logical, as adrenergic fibers can release noradrenalin necessary to activate β3-AR [37].

Scarce and controversial information regarding β3-AR presence in the kidney has been reported up to date, with some publications describing functional and transcriptional evidence [38][39][40] while some others fail to report its presence at all [17]. Recently, we provided evidence regarding the localization of β3-AR to the vasopressin-sensitive segments of the mouse nephron. The agonist BRL37344 was used on freshly isolated kidney tubules and slices from wt and β3-AR knock out (KO) mice to demonstrate β3-AR coupling to Gs/adenylyl cyclase and its positive effects on key water and solute transporters, such as Aquaporin 2 (AQP2) and Na-K-2Cl (NKCC2). All effects reported were blocked upon pre-incubation with the antagonist L748337 or PKA inhibitor H89, suggesting a potential activation of the cAMP/PKA axis. Ex vivo findings are strengthened by in vivo data, showing that KO mice for β3-AR are mildly polyuric and highlighting a role for β3-AR in renal homeostasis. Interestingly, administration of BRL37344 to a mouse model of X-linked nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (NDI), known to be heavily polyuric, completely reverted the phenotype within 1 h from injection [18]. In light of these findings, it is tempting to speculate on the use of β3-AR as therapeutic target in conditions where water-solute homeostasis and/or vasopressin signaling are impaired (see Section 6).

β3-AR are also present in the lower urinary tract where they undergo pathophysiological changes in expression upon the initiation of lower urinary tract symptoms due to ureteral stenosis [20], chronic kidney disease, end stage renal disease, or certain carcinomas [41]. The β3-AR agonist mirabegron for the oral pharmacotherapy of patients affected by overactive bladder syndrome (OAB) is currently the most promising agent in over 30 years. This drug has been extensively studied, with a good number of Phase II and Phase III trials all over the world, exhibiting a good balance between efficacy and tolerability in all of them [42]. It was licensed for the treatment of OAB and approved for use in Japan in 2011 (Betanis), USA and Canada in 2012 (Myrbetriq), and Europe in 2013 (Betmiga). Safety and tolerability of mirabegron in the treatment of OAB have been extensively reviewed by Michel et al. [43]. Several repurposing studies are currently exploring potential uses for mirabegron in the treatment of heart and metabolic conditions. Other molecules have made it to Phase III clinical trials: ritobegron however appears to have been discontinued (Clinicaltrials.gov, NCT01003405) while the new potent and selective β3-AR agonist, vibegron, has recently passed the later stages [44] and has been approved in Japan for the treatment of OAB [45].

2.2. Adipose Tissue

β3-AR is abundantly expressed in rodent white (WAT) and brown (BAT) adipose tissue where it mediates lipolysis and thermogenesis [2][46]. In humans, β3-AR mRNA levels appeared to be much lower in these tissues. The transcript was mainly identified in infant peri-renal BAT and in various deposits of WAT in the adults [7][47] while its presence at the protein level was published later through the use of a monoclonal antibody directed against the human receptor [48][49]. Of note, one of the greatest obstacles in the study of β3-AR role and function in humans is represented by the little presence of BAT in adults; however, studies in the last decade are overturning these findings, showing proof for a metabolic role of BAT in healthy adults [50][51]. Similarly, to rodents, selective activation of β3-AR stimulates lipolysis in human isolated white adipocytes [52][53].

A major trigger of both lipolysis and thermogenesis is the sympathetic nervous system. From a molecular point of view, noradrenaline (NA) released by sympathetic nerve endings binds to β3-AR, which couples to the α-subunit of Gs-proteins and triggers the activation of the cAMP-PKA axis. Final targets of this cascade include lipid droplet proteins, like hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) and perilipin, that start the lipolytic process in white adipocytes. However, β3-AR signaling in adipocytes is promiscuous in that HSL activation can also be triggered by β3-AR coupling to Gi and consequent initiation of the ERK1/2 MAP kinase cascade [54][55]. The net result is the release of free fatty acids (FFAs) derived from the hydrolysis of triglycerides stored in the lipid droplet. In brown adipocytes FFAs activate Uncoupling-Protein 1 (UCP1) in the mitochondria, triggering thermogenesis. Of note, β3-AR activation can also lead to lipolysis by increasing the transcription/expression of the inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and thus nitric oxide levels in a PKA-dependent fashion [56].

β3-AR activation was recently found to be involved in the generation of hyperthermia arising from WAT, instead of the more classically thermogenic BAT, with simultaneous WAT remodeling and increased beiging in mice with impairment in triglyceride storage capabilities [57]. β3-AR KO mice also showed impaired cold-induced thermogenesis with a reduction in white adipocyte beiging [58]. This is consistent with recent findings that β3-AR activation induces trans-differentiation of mature white adipocytes but that cold-induced beiging occurs via β1-AR [59]. In contrast, others argued that β3-AR is dispensable for thermogenesis, showing that adaptive response to cold is not affected in KO mice [60].

Regardless of these effects, β3-AR KO mice lack a major phenotype, with only moderate fat accumulation in females vs. males and no altered adipose-related functional response to β-agonists [61]. KO mice also show a compensatory over-expression of β1-AR in WAT and BAT and they are able to survive cold exposure through β1-AR mediated thermogenesis and UCP1 increase [61][62]. More recent findings, however, reported that β3-AR KO mice generated on the same background show an increased susceptibility to high fat diet, developing more severe obesity with white adipocyte hypertrophy and inflammation in comparison to wild type mice [63]. Consistently, Hong at al showed that the ERK-β3-AR axis is a key player in obesity-driven increases in lipolysis and that administration of MEK inhibitors is efficient in blunting both in vivo lipolysis in diet-induced obese mice and ex vivo lipolysis induced by β3-AR agonist treatment on human and murine WAT explants [64].

Lipid and carbohydrate metabolism are influenced by β3-AR agonists with normalizing effects on hyperinsulinemia, increases in resting energy expenditure (REE) and decreases in circulating FFAs, fat/non-fat mass ratio and body weight gain in rats or in obese mice [65][66][67]. In humans, β3-AR expression level is reduced in obese patients [49]. These observations raised interest in the development of compounds for the treatment of obesity and type 2 diabetes [68][69], but clinical studies [70][71] were disappointing due to poor selectivity of the drugs for the human β3-AR and different contributions of white and brown adipocytes in rodents and humans [72].

No agonist has yet progressed beyond phase II clinical trials. It is unclear whether this is because of the lack of compounds with suitable drug properties (e.g., oral bioavailability), because of a lesser role for β3-AR in modulating adipogenesis in humans than in rodents or due to the little presence of BAT in adults, although this concept has been challenged in the last decade [50][51]. However, there is still active speculation in regard to β3-AR as a target for metabolic conditions. A short review by Jonathan Arch. discusses this long-standing issue, proposing some alternatives like combined administration of β3-AR agonists and other compounds aimed at increasing BAT amount in patients [73]. A recent study investigated the repurposing of mirabegron, determining its ability to stimulate BAT activity and REE in healthy subjects [74]. Despite study limitations of size and gender, these findings show that administration of supra-therapeutic doses of mirabegron leads to an increase in REE via cardiovascular stimulation and BAT activation but also causes unwanted cardiovascular effects, likely due to β1-AR off-target binding. Finally, even in cases where weight reduction is not achieved, β3-AR stimulation could generally exert positive metabolic effects [74]. This study might contribute to the re-opening of a debate about β3-AR role as a possible candidate for the treatment of obesity and metabolic diseases, highlighting the necessity for the development of more subtype-selective agonists so as to limit side effects to a minimum.

Along the same line and based on all these pre-clinical and clinical considerations, new beta-phenylethylamine compounds were recently synthetized and tested in rats with alloxan-induced type II diabetes. All of these compounds markedly decreased levels of total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and triglycerides and increased the values of antiatherogenic HDL cholesterol. Moreover, the effects were significantly more intense than the reference substance BRL37344 [75]. In light of these considerations it appears that, although theoretically appealing, the amount of data that is currently available is not enough for β3-AR agonists to proceed into a clinical stage and more insights into the receptor physiology are ultimately needed for this purpose.

References

- Granneman, J.G.; Lahners, K.N.; Chaudhry, A. Molecular cloning and expression of the rat β3-adrenergic receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 1991, 40, 895–899.

- Nahmias, C.; Blin, N.; Elalouf, J.M.; Mattei, M.G.; Strosberg, A.D.; Emorine, L.J. Molecular characterization of the mouse β3-adrenergic receptor: Relationship with the atypical receptor of adipocytes. EMBO J. 1991, 10, 3721–3727.

- Forrest, R.H.; Hickford, J.G. Rapid communication: Nucleotide sequences of the bovine, caprine, and ovine beta3-adrenergic receptor genes. J. Anim. Sci. 2000, 78, 1397–1398.

- Sasaki, N.; Uchida, E.; Niiyama, M.; Yoshida, T.; Saito, M. Anti-obesity effects of selective agonists to the β3-adrenergic receptor in dogs. I. The presence of canine β3-adrenergic receptor and in vivo lipomobilization by its agonists. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 1998, 60, 459–463.

- Jockers, R.; Da Silva, A.; Strosberg, A.D.; Bouvier, M.; Marullo, S. New molecular and structural determinants involved in β2-adrenergic receptor desensitization and sequestration. Delineation using chimeric β3/β2-adrenergic receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 9355–9362.

- Nantel, F.; Bonin, H.; Emorine, L.J.; Zilberfarb, V.; Strosberg, A.D.; Bouvier, M.; Marullo, S. The human β3-adrenergic receptor is resistant to short term agonist-promoted desensitization. Mol. Pharmacol. 1993, 43, 548–555.

- Granneman, J.G.; Lahners, K.N.; Chaudhry, A. Characterization of the human β3-adrenergic receptor gene. Mol. Pharmacol. 1993, 44, 264–270.

- Van Spronsen, A.; Nahmias, C.; Krief, S.; Briend-Sutren, M.M.; Strosberg, A.D.; Emorine, L.J. The promoter and intron/exon structure of the human and mouse β3-adrenergic-receptor genes. Eur. J. Biochem. 1993, 213, 1117–1124.

- Evans, B.A.; Papaioannou, M.; Hamilton, S.; Summers, R.J. Alternative splicing generates two isoforms of the β3-adrenoceptor which are differentially expressed in mouse tissues. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999, 127, 1525–1531.

- Hutchinson, D.S.; Bengtsson, T.; Evans, B.A.; Summers, R.J. Mouse β3a- and β3b-adrenoceptors expressed in chinese hamster ovary cells display identical pharmacology but utilize distinct signalling pathways. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002, 135, 1903–1914.

- Milano, S.; Gerbino, A.; Schena, G.; Carmosino, M.; Svelto, M.; Procino, G. Human β3-adrenoreceptor is resistant to agonist-induced desensitization in renal epithelial cells. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 48, 847–862.

- Okeke, K.; Angers, S.; Bouvier, M.; Michel, M.C. Agonist-induced desensitisation ofβ3-adrenoceptors: Where, when and how? Br. J. Pharmacol. 2019.

- Lefkowitz, R.J. G protein-coupled receptors. III. New roles for receptor kinases and β-arrestins in receptor signaling and desensitization. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 18677–18680.

- Michel-Reher, M.B.; Michel, M.C. Agonist-induced desensitization of human β3-adrenoceptors expressed in human embryonic kidney cells. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2013, 386, 843–851.

- Strosberg, A.D.; Pietri-Rouxel, F. Function and regulation of the β3-adrenoceptor. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1996, 17, 373–381.

- Moffett, S.; Mouillac, B.; Bonin, H.; Bouvier, M. Altered phosphorylation and desensitization patterns of a human β2-adrenergic receptor lacking the palmitoylated Cys341. EMBO J. 1993, 12, 349–356.

- Uhlen, M.; Fagerberg, L.; Hallstrom, B.M.; Lindskog, C.; Oksvold, P.; Mardinoglu, A.; Sivertsson, A.; Kampf, C.; Sjostedt, E.; Asplund, A.; et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 2015, 347, 1260419.

- Procino, G.; Carmosino, M.; Milano, S.; Dal Monte, M.; Schena, G.; Mastrodonato, M.; Gerbino, A.; Bagnoli, P.; Svelto, M. Beta3 adrenergic receptor in the kidney may be a new player in sympathetic regulation of renal function. Kidney Int. 2016, 90, 555–567.

- Michel, M.C.; Vrydag, W. α1-, α2- and β-adrenoceptors in the urinary bladder, urethra and prostate. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 147 (Suppl. 2), S88–S119.

- Shen, H.; Chen, Z.; Mokhtar, A.D.; Bi, X.; Wu, G.; Gong, S.; Huang, C.; Li, S.; Du, S. Expression of beta-adrenergic receptor subtypes in human normal and dilated ureter. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2017, 49, 1771–1778.

- Limberg, B.J.; Andersson, K.E.; Aura Kullmann, F.; Burmer, G.; de Groat, W.C.; Rosenbaum, J.S. β-adrenergic receptor subtype expression in myocyte and non-myocyte cells in human female bladder. Cell Tissue Res. 2010, 342, 295–306.

- Calmasini, F.B.; Candido, T.Z.; Alexandre, E.C.; D’Ancona, C.A.; Silva, D.; de Oliveira, M.A.; De Nucci, G.; Antunes, E.; Monica, F.Z. The β-3 adrenoceptor agonist, mirabegron relaxes isolated prostate from human and rabbit: New therapeutic indication? Prostate 2015, 75, 440–447.

- Otsuka, A.; Shinbo, H.; Matsumoto, R.; Kurita, Y.; Ozono, S. Expression and functional role of β-adrenoceptors in the human urinary bladder urothelium. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2008, 377, 473–481.

- Yamaguchi, O. β3-adrenoceptors in human detrusor muscle. Urology 2002, 59, 25–29.

- Nergardh, A.; Boreus, L.O.; Naglo, A.S. Characterization of the adrenergic beta-receptor in the urinary bladder of man and cat. Acta Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1977, 40, 14–21.

- Larsen, J.J. Alpha and beta-adrenoceptors in the detrusor muscle and bladder base of the pig and β-adrenoceptors in the detrusor muscle of man. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1979, 65, 215–222.

- Wuest, M.; Eichhorn, B.; Grimm, M.O.; Wirth, M.P.; Ravens, U.; Kaumann, A.J. Catecholamines relax detrusor through β2-adrenoceptors in mouse and β3-adrenoceptors in man. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2009, 328, 213–222.

- Igawa, Y.; Yamazaki, Y.; Takeda, H.; Hayakawa, K.; Akahane, M.; Ajisawa, Y.; Yoneyama, T.; Nishizawa, O.; Andersson, K.E. Functional and molecular biological evidence for a possible β3-adrenoceptor in the human detrusor muscle. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999, 126, 819–825.

- Peirce, V.; Carobbio, S.; Vidal-Puig, A. The different shades of fat. Nature 2014, 510, 76–83.

- Tagaya, E.; Tamaoki, J.; Takemura, H.; Isono, K.; Nagai, A. Atypical adrenoceptor-mediated relaxation of canine pulmonary artery through a cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent pathway. Lung 1999, 177, 321–332.

- Tanaka, Y.; Horinouchi, T.; Koike, K. New insights into beta-adrenoceptors in smooth muscle: Distribution of receptor subtypes and molecular mechanisms triggering muscle relaxation. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2005, 32, 503–514.

- Uchida, H.; Shishido, K.; Nomiya, M.; Yamaguchi, O. Involvement of cyclic amp-dependent and -independent mechanisms in the relaxation of rat detrusor muscle via β-adrenoceptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2005, 518, 195–202.

- Maki, T.; Kajioka, S.; Itsumi, M.; Kareman, E.; Lee, K.; Shiota, M.; Eto, M. Mirabegron induces relaxant effects via camp signaling-dependent and -independent pathways in detrusor smooth muscle. Low. Urin. Tract Symptoms 2019.

- Frazier, E.P.; Mathy, M.J.; Peters, S.L.; Michel, M.C. Does cyclic amp mediate rat urinary bladder relaxation by isoproterenol? J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005, 313, 260–267.

- Michel, M.C.; Korstanje, C. Beta3-adrenoceptor agonists for overactive bladder syndrome: Role of translational pharmacology in a repositioning clinical drug development project. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 159, 66–82.

- Patel, H.J.; Giembycz, M.A.; Keeling, J.E.; Barnes, P.J.; Belvisi, M.G. Inhibition of cholinergic neurotransmission in guinea pig trachea by ns1619, a putative activator of large-conductance, calcium-activated potassium channels. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998, 286, 952–958.

- Coelho, A.; Antunes-Lopes, T.; Gillespie, J.; Cruz, F. β-3 adrenergic receptor is expressed in acetylcholine-containing nerve fibers of the human urinary bladder: An immunohistochemical study. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2017, 36, 1972–1980.

- Kaufmann, J.; Martinka, P.; Moede, O.; Sendeski, M.; Steege, A.; Fahling, M.; Hultstrom, M.; Gaestel, M.; Moraes-Silva, I.C.; Nikitina, T.; et al. Noradrenaline enhances angiotensin ii responses via p38 mapk activation after hypoxia/re-oxygenation in renal interlobar arteries. Acta Physiol. 2015, 213, 920–932.

- Rojek, A.; Nielsen, J.; Brooks, H.L.; Gong, H.; Kim, Y.H.; Kwon, T.H.; Frokiaer, J.; Nielsen, S. Altered expression of selected genes in kidney of rats with lithium-induced ndi. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 2005, 288, F1276–F1289.

- Rains, S.L.; Amaya, C.N.; Bryan, B.A. β-adrenergic receptors are expressed across diverse cancers. Oncoscience 2017, 4, 95–105.

- Chen, S.F.; Lee, C.L.; Kuo, H.C. Changes in sensory proteins in the bladder urothelium of patients with chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease. Low. Urin. Tract Symptoms 2018.

- Chapple, C.R.; Cardozo, L.; Nitti, V.W.; Siddiqui, E.; Michel, M.C. Mirabegron in overactive bladder: A review of efficacy, safety, and tolerability. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2014, 33, 17–30.

- Michel, M.C.; Gravas, S. Safety and tolerability of β3-adrenoceptor agonists in the treatment of overactive bladder syndrome-insig.ht from transcriptosome and experimental studies. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016, 15, 647–657.

- Yoshida, M.; Takeda, M.; Gotoh, M.; Nagai, S.; Kurose, T. Vibegron, a novel potent and selective β3-adrenoreceptor agonist, for the treatment of patients with overactive bladder: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Eur. Urol. 2018, 73, 783–790.

- Keam, S.J. Vibegron: First global approval. Drugs 2018, 78, 1835–1839.

- Arch, J.R.; Ainsworth, A.T.; Cawthorne, M.A.; Piercy, V.; Sennitt, M.V.; Thody, V.E.; Wilson, C.; Wilson, S. Atypical β-adrenoceptor on brown adipocytes as target for anti-obesity drugs. Nature 1984, 309, 163–165.

- Krief, S.; Lonnqvist, F.; Raimbault, S.; Baude, B.; Van Spronsen, A.; Arner, P.; Strosberg, A.D.; Ricquier, D.; Emorine, L.J. Tissue distribution of β3-adrenergic receptor mrna in man. J. Clin. Investig. 1993, 91, 344–349.

- Chamberlain, P.D.; Jennings, K.H.; Paul, F.; Cordell, J.; Berry, A.; Holmes, S.D.; Park, J.; Chambers, J.; Sennitt, M.V.; Stock, M.J.; et al. The tissue distribution of the human β3-adrenoceptor studied using a monoclonal antibody: Direct evidence of the β3-adrenoceptor in human adipose tissue, atrium and skeletal muscle. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord 1999, 23, 1057–1065.

- De Matteis, R.; Arch, J.R.; Petroni, M.L.; Ferrari, D.; Cinti, S.; Stock, M.J. Immunohistochemical identification of the β3-adrenoceptor in intact human adipocytes and ventricular myocardium: Effect of obesity and treatment with ephedrine and caffeine. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord 2002, 26, 1442–1450.

- Cypess, A.M.; Lehman, S.; Williams, G.; Tal, I.; Rodman, D.; Goldfine, A.B.; Kuo, F.C.; Palmer, E.L.; Tseng, Y.H.; Doria, A.; et al. Identification and importance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 1509–1517.

- Hibi, M.; Oishi, S.; Matsushita, M.; Yoneshiro, T.; Yamaguchi, T.; Usui, C.; Yasunaga, K.; Katsuragi, Y.; Kubota, K.; Tanaka, S.; et al. Brown adipose tissue is involved in diet-induced thermogenesis and whole-body fat utilization in healthy humans. Int. J. Obes. 2016, 40, 1655–1661.

- Sennitt, M.V.; Kaumann, A.J.; Molenaar, P.; Beeley, L.J.; Young, P.W.; Kelly, J.; Chapman, H.; Henson, S.M.; Berge, J.M.; Dean, D.K.; et al. The contribution of classical (β1/2-) and atypical beta-adrenoceptors to the stimulation of human white adipocyte lipolysis and right atrial appendage contraction by novel β3-adrenoceptor agonists of differing selectivities. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1998, 285, 1084–1095.

- Tavernier, G.; Barbe, P.; Galitzky, J.; Berlan, M.; Caput, D.; Lafontan, M.; Langin, D. Expression of β3-adrenoceptors with low lipolytic action in human subcutaneous white adipocytes. J. Lipid Res. 1996, 37, 87–97.

- Robidoux, J.; Kumar, N.; Daniel, K.W.; Moukdar, F.; Cyr, M.; Medvedev, A.V.; Collins, S. Maximal β3-adrenergic regulation of lipolysis involves src and epidermal growth factor receptor-dependent ERK1/2 activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 37794–37802.

- Soeder, K.J.; Snedden, S.K.; Cao, W.; Della Rocca, G.J.; Daniel, K.W.; Luttrell, L.M.; Collins, S. The β3-adrenergic receptor activates mitogen-activated protein kinase in adipocytes through a Gi-dependent mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 12017–12022.

- Hodis, J.; Vaclavikova, R.; Farghali, H. β-3 agonist-induced lipolysis and nitric oxide production: Relationship to ppargamma agonist/antagonist and amp kinase modulation. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 2011, 30, 90–99.

- Banfi, S.; Gusarova, V.; Gromada, J.; Cohen, J.C.; Hobbs, H.H. Increased thermogenesis by a noncanonical pathway in angptl3/8-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E1249–E1258.

- Barbatelli, G.; Murano, I.; Madsen, L.; Hao, Q.; Jimenez, M.; Kristiansen, K.; Giacobino, J.P.; De Matteis, R.; Cinti, S. The emergence of cold-induced brown adipocytes in mouse white fat depots is determined predominantly by white to brown adipocyte transdifferentiation. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 298, E1244–E1253.

- Jiang, Y.; Berry, D.C.; Graff, J.M. Distinct cellular and molecular mechanisms for β3 adrenergic receptor-induced beige adipocyte formation. Elife 2017, 6, e30329.

- De Jong, J.M.A.; Wouters, R.T.F.; Boulet, N.; Cannon, B.; Nedergaard, J.; Petrovic, N. The β3-adrenergic receptor is dispensable for browning of adipose tissues. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 312, E508–E518.

- Susulic, V.S.; Frederich, R.C.; Lawitts, J.; Tozzo, E.; Kahn, B.B.; Harper, M.E.; Himms-Hagen, J.; Flier, J.S.; Lowell, B.B. Targeted disruption of the β3-adrenergic receptor gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 29483–29492.

- Mattsson, C.L.; Csikasz, R.I.; Chernogubova, E.; Yamamoto, D.L.; Hogberg, H.T.; Amri, E.Z.; Hutchinson, D.S.; Bengtsson, T. β1-Adrenergic receptors increase UCP1 in human MADS brown adipocytes and rescue cold-acclimated β3-adrenergic receptor-knockout mice via nonshivering thermogenesis. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 301, E1108–E1118.

- Preite, N.Z.; Nascimento, B.P.; Muller, C.R.; Americo, A.L.; Higa, T.S.; Evangelista, F.S.; Lancellotti, C.L.; Henriques, F.S.; Batista, M.L., Jr.; Bianco, A.C.; et al. Disruption of β3 adrenergic receptor increases susceptibility to dio in mouse. J. Endocrinol. 2016, 231, 259–269.

- Hong, S.; Song, W.; Zushin, P.H.; Liu, B.; Jedrychowski, M.P.; Mina, A.I.; Deng, Z.; Cabarkapa, D.; Hall, J.A.; Palmer, C.J.; et al. Phosphorylation of β-3 adrenergic receptor at serine 247 by erk map kinase drives lipolysis in obese adipocytes. Mol. Metab. 2018, 12, 25–38.

- Decara, J.; Rivera, P.; Arrabal, S.; Vargas, A.; Serrano, A.; Pavon, F.J.; Dieguez, C.; Nogueiras, R.; Rodriguez de Fonseca, F.; Suarez, J. Cooperative role of the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor and β3-adrenergic-mediated signalling on fat mass reduction through the downregulation of pka/akt/ampk signalling in the adipose tissue and muscle of rats. Acta Physiol. 2018, 222, e13008.

- Clookey, S.L.; Welly, R.J.; Shay, D.; Woodford, M.L.; Fritsche, K.L.; Rector, R.S.; Padilla, J.; Lubahn, D.B.; Vieira-Potter, V.J. β3 adrenergic receptor activation rescues metabolic dysfunction in female estrogen receptor alpha-null mice. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 9.

- Xiao, C.; Goldgof, M.; Gavrilova, O.; Reitman, M.L. Anti-obesity and metabolic efficacy of the β3-adrenergic agonist, CL316243, in mice at thermoneutrality compared to 22 °C. Obesity 2015, 23, 1450–1459.

- Bhadada, S.V.; Patel, B.M.; Mehta, A.A.; Goyal, R.K. β3 receptors: Role in cardiometabolic disorders. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 2, 65–79.

- Oana, F.; Takeda, H.; Matsuzawa, A.; Akahane, S.; Isaji, M.; Akahane, M. Adiponectin receptor 2 expression in liver and insulin resistance in DB/DB mice given a β3-adrenoceptor agonist. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2005, 518, 71–76.

- Larsen, T.M.; Toubro, S.; van Baak, M.A.; Gottesdiener, K.M.; Larson, P.; Saris, W.H.; Astrup, A. Effect of a 28-d treatment with L-796568, a novel β3-adrenergic receptor agonist, on energy expenditure and body composition in obese men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 76, 780–788.

- Van Baak, M.A.; Hul, G.B.; Toubro, S.; Astrup, A.; Gottesdiener, K.M.; DeSmet, M.; Saris, W.H. Acute effect of L-796568, a novel β3-adrenergic receptor agonist, on energy expenditure in obese men. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2002, 71, 272–279.

- Michel, M.C.; Ochodnicky, P.; Summers, R.J. Tissue functions mediated by β3-adrenoceptors-findings and challenges. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2010, 382, 103–108.

- Arch, J.R. Challenges in β3-adrenoceptor agonist drug development. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 2, 59–64.

- Baskin, A.S.; Linderman, J.D.; Brychta, R.J.; McGehee, S.; Anflick-Chames, E.; Cero, C.; Johnson, J.W.; O’Mara, A.E.; Fletcher, L.A.; Leitner, B.P.; et al. Regulation of human adipose tissue activation, gallbladder size, and bile acid metabolism by a β3-adrenergic receptor agonist. Diabetes 2018, 67, 2113–2125.

- Negreș, S.; Chiriță, C.; Arsene, A.L.; Margină, D.; Moroșan, E.; Zbârcea, C.E. New potential β-3 adrenergic agonists with β-phenylethylamine structure, synthesized for the treatment of dyslipidemia and obesity. In Adiposity: Epidemiology and Treatment Modalities; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2017.

More

Information

Subjects:

Cell Biology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

2.2K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

05 May 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No