Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jae-Young Jeong | -- | 2292 | 2022-04-27 11:36:42 | | | |

| 2 | Dean Liu | -10 word(s) | 2282 | 2022-04-28 03:48:02 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Jeong, J.; Cho, M.; Lee, M. Effect of Non-Parking Facilities in Parking-Only Buildings. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22364 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Jeong J, Cho M, Lee M. Effect of Non-Parking Facilities in Parking-Only Buildings. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22364. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Jeong, Jae-Young, Mi-Jeong Cho, Myeong-Hun Lee. "Effect of Non-Parking Facilities in Parking-Only Buildings" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22364 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Jeong, J., Cho, M., & Lee, M. (2022, April 27). Effect of Non-Parking Facilities in Parking-Only Buildings. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22364

Jeong, Jae-Young, et al. "Effect of Non-Parking Facilities in Parking-Only Buildings." Encyclopedia. Web. 27 April, 2022.

Copy Citation

The designation parking-only building (POB) was first introduced in the Parking Lot Act on 14 December 1991. According to the law, POBs can be used for purposes other than parking facilities, that is, non-parking facilities (NPFs), up to 70% of the total floor area. In addition, the POB is an infrastructure in accordance with the National Land Planning and Utilization Act.

parking-only buildings

non-parking facilities

change of use

traffic

1. Introduction

The increasing population in large cities and the unbalanced urban growth associated with massive use of private cars in metropolitan areas often lead to traffic jams and road congestion that warrant the construction of such capital-intensive buildings as off-street parking facilities [1]. The government is deregulating POBs and strengthening construction support, such as allowing housing installations in POBs to improve the sale-ability of POBs and revitalize the supply of parking facilities in downtown areas [2]. As a result, the off-street parking lot, which was mainly used two-dimensionally, was used three-dimensionally and complexly, which improved the efficiency of land use and increased the possibility of providing complex services. The use of POBs can have a positive effect, enabling transit-oriented development (TOD), a near-workplace city, low-carbon, an energy-saving city, and a compact city [3][4][5][6][7][8].

However, on the other hand, the focus is on the commercial use of NPFs rather than the supply of parking lots, which has the adverse effect of transforming parking facilities into warehouses of NPFs or into annexed parking lots [9]. Due to this problem of change of use, there are cases in which the supply of POBs promoted by the private investment method BTO (build-transfer-operate) is canceled due to opposition from local residents [10][11].

There are opposing views on POBs. As a result of LHI’s expert perception survey in 2015, the opinion that private business operators should increase the ratio of NPFs to promote POB sales was 50.0%, which was higher than that of other occupational groups. On the other hand, researchers from research institutes answered that the ratio of NPFs should be reduced (34.6%) and public officials said that the current regulations are appropriate (31.8%). Additionally, in the case of university professors, other opinions (42.9%) were high. Specific opinions include “Differential application according to location and use”, “Considering the sale situation, it is inevitable to maintain the current regulations”, “Adjust the ratio of NPFs according to local demand”, “Need criteria for determining the suitability of the ratio of NPFs”, “The demand for parking at NPFs erodes the demand for parking facilities, so the demand for parking at NPFs is excluded from the demand for parking facilities and secured separately” [12].

To solve this problem, appropriate standards are needed, and the current National Land Planning and Utilization Act (hereinafter referred to as the “National Land Planning Act”) and the Parking Lot Act stipulates the ratio and allowable use of NPFs. However, what is important here is whether the various types of NPFs equally weaken the public interest of the parking lot. It is necessary to prepare relevant standards through research on NPFs. Recently the Supreme Court also pointed out that in the case of the Audi maintenance center in Naegok-dong, it is necessary to prepare detailed installation standards for parking auxiliary facilities [13].

If a neighborhood living facility or sales facility is introduced as a NPF in a POB, it will face opposition from nearby merchants, and if a rental house is introduced, it will face opposition from rental business [14]. In addition, through the case of a transfer center in the station area developed by the private sector, an ironic situation can occur that rather induces traffic demand by attracting non-parking facilities centered on sales facilities [15].

Based on this awareness, research on parking-only buildings is necessary, but research so far has mainly focused on off-street parking lots in residential land development districts. Accordingly, researchers aim to suggest implications for establishing parking-related policies by examining the current status of NPF use of POBs located in 31 cities and counties in Gyeonggi-do, establishing the concept of traffic inducement rate (TIR), and analyzing factors affecting it.

The spatial scope was targeted at 302 POBs in Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea. Since Gyeonggi-do is a metropolitan government with a considerable number of POBs, it was determined that the analysis target could be secured, and the characteristics of 31 cities in Gyeonggi-do could be compared. The temporal scope of the study was based on 2020 when a list of POBs was obtained from local governments.

The contents can be divided into the data collection process through literature research and the statistical analysis process of the collected data. First, a list of POBs was obtained from the local government, and basic data such as the NPF usage status were investigated through building registers for each POB. Next, the TIR was calculated using the traffic inducement coefficient (TIC) according to the Urban Traffic Improvement Promotion Act. In addition, variables affecting the TIR were selected through review of existing studies and literature. Finally, significant influencing factors were extracted through multiple linear regression analysis (MLRA).

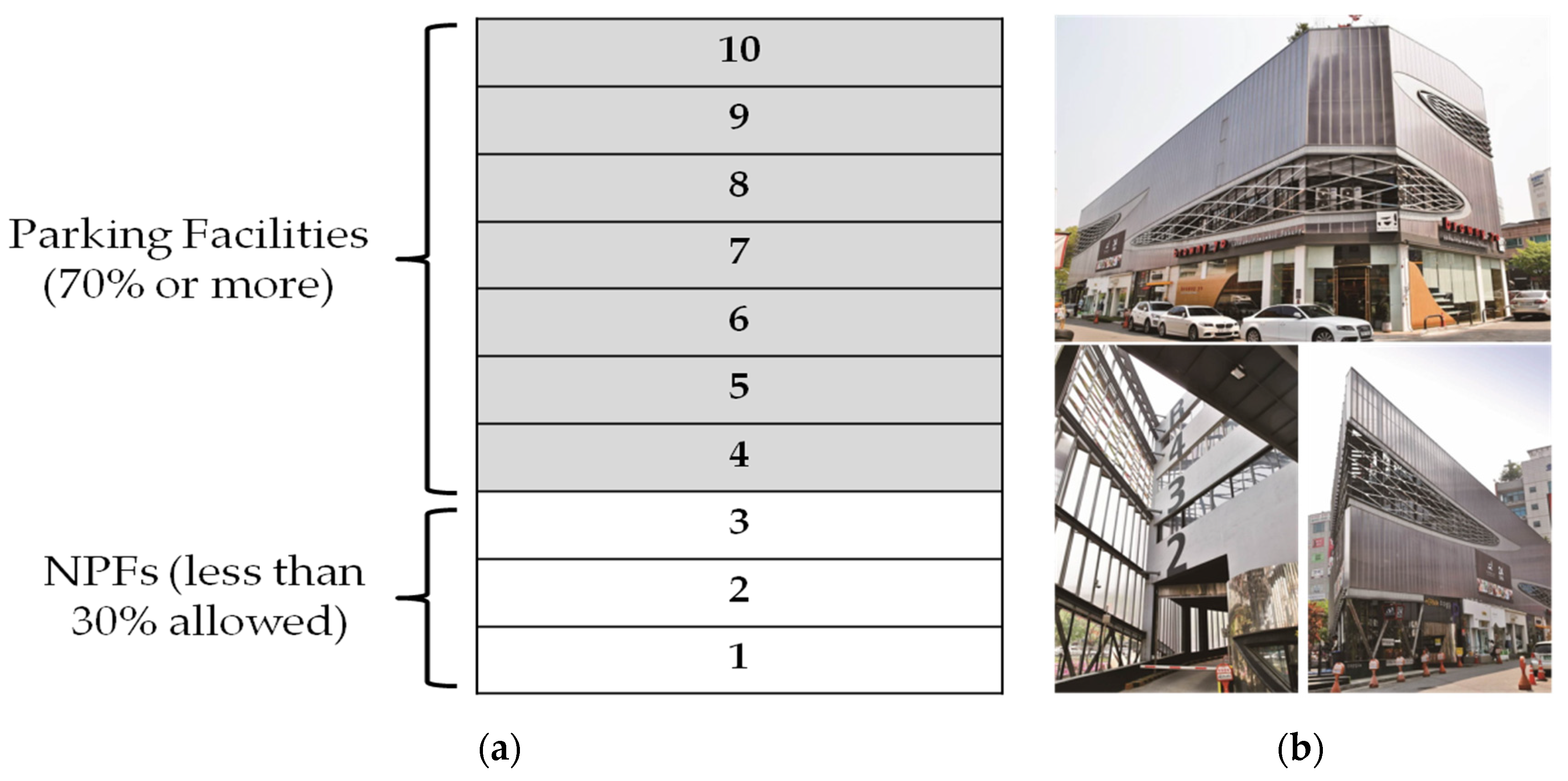

Figure 1. (a) Is a POB concept drawing on the premise of the 10th floor (drawings by the author based on [16][17]), (b) Is a picture of Herma POB in 8–19, Jukjeon-ro 15beon-gil, Giheung-gu, Yongin city, Gyeonggi-do, Korea [18].

2. Legal Status of Parking-Only Buildings

The legal transition process was investigated in relation to the legal definition of a POB, the subject of the study, and the permitted use of NPFs.

2.1. Concept of Parking-Only Building

A POB uses more than 95% of the total area of the building as parking facilities. However, when NPFs are installed in the POB, 70% of the total area of the POB can be used as parking facilities. NPFs are detached houses, apartment houses, type 1 neighborhood living facilities, type 2 neighborhood living facilities, cultural and congregational facilities, religious facilities, sales facilities, transportation facilities, sports facilities, office facilities, warehouse facilities, and automobile-related facilities [16][17]. A POB is a type of off-street parking lot, which is an infrastructure according to the National Land Planning Act, and is a public facility (limited to parking lots installed by administrative agencies) where ownership is transferred to local governments free of charge after completion. It is also a facility that can be designated as an urban planning facility that requires strong public interest [19][20]. In accordance with the Enforcement Decree of the Parking Lot Act, there is no need to install a separate parking lot except for sales facilities (department stores, shopping centers, large stores) and cultural and congregationalfacilities (movies, exhibition halls, wedding halls) among NPFs [21]. In addition, in accordance with the Special Cases of the Parking Lot Act, the building-to-land ratio, floor area ratio, minimum site area, and height restrictions of buildings exclusively for parking may be differently determined as follows, notwithstanding the National Land Planning Act [22].

-

Building-to-land ratio: 90% or less

-

Floor area ratio: 1500% or less

-

Minimum site area: 45 m2 or more

-

Height restriction:

- -

-

When the site is in contact with a road less than 12 m in width: The height of each part of the building is three times the horizontal distance from that part to the boundary line on the opposite side of the road in contact with the site;

- -

-

When the site is in contact with a road with a width of 12 m or more: The height of each part of the building is 36 times the horizontal distance from that part to the boundary line on the opposite side of the road facing the site/times the width of the road (1.8 times if the magnification is less than 1.8 times).

2.2. Parking Lot Law Change Process

Over time, researchers investigated how the government changed the parking lot law as a policy, and what NPFs were allowed for POBs. In order to actively cope with the urban parking problem, which is getting worse day by day due to the rapid increase of automobiles, dedicated parking buildings are emerging. At the time of the enactment of the Parking Lot Act (17 April 1979), there was no mention of a POB [23]. However, due to the revision of the Parking Lot Act (31 March 1983), the part of the parking lot with buildings exceeding the statutory area was allowed to be converted into an off-street parking lot [24]. This can be seen as the beginning of the POB. The first POB was specified in the Act on 14 December 1991 when the Parking Lot Act was amended. In the revised law, standards such as building-to-land ratio and floor area ratio, minimum site area and height restrictions were entrusted to the Enforcement Decree [25].In 1992, the ratio of parking facilities was divided into 70%, 80%, and 90% based on whether the POB was decided as an urban planning facility and had a total floor area of 1000m2. The types of NPFs were the same as before [26]. In 1995, when POB was an urban planning facility, the ratio of permitted uses other than parking lots was expanded to 20%, and office facilities, sports facilities, and exhibition facilities were added to permitted uses [27]. In 1996, to promote the creation of parking lots, the ratio of NPFs was increased to 30% regardless of the presence or absence of urban planning facilities or the total floor area, and sales facilities and viewing hall facilities were added as permissible uses. The obligation to install an attached parking lot to NPFs was also exempted. In consideration of the conditions between local governments, the permitted use of NPFs was restricted in some areas through the ordinance [28]. In 1999, cultural facilities and office facilities were added as permitted uses for NPFs [29]. In 2007, religious facilities and transportation facilities were added as permitted uses for NPFs [30], and detached houses and apartment houses were added in 2014 [31]. In 2016, a warehouse facility was added [32] (Table 1).

Table 1. Change of ratio of NPFs and permitted use according to the revision of the Parking Lot Act.

| Year | Percentage of NPFs and Permitted Uses |

|---|---|

| 1992 | <Urban planning facility> 90%: Neighborhood living facility, automobile-related facility, and neighborhood public facility <Non-urban planning facility>

|

| 1995 | <Urban planning facility> 80%: Neighborhood living facility, automobile-related facility, neighborhood public facility, office facility, sports facility, and exhibition facility <Non-urban planning facility>

|

| 1996 | 70%: Neighborhood living facility, automobile-related facility, neighborhood public facility, office facility, sports facility, exhibition facility, sales facility, and viewing and congregational facility |

| 1999 | 70%: Type 1 and type 2 neighborhood living facility, cultural and congregational facility, sales and business facility, sports facility, office facility, and automobile-related facility |

| 2007 | 70%: Type 1 and type 2 neighborhood living facility, cultural and congregational facility, religious facility, sales facility, transportation facility, sports facility, office facility, and automobile-related facility |

| 2014 | 70%: Detached house, apartment house, type 1 and type 2 neighborhood living facility, cultural and congregational facility, religious facility, sales facility, transportation facility, sports facility, office facility, and automobile-related facility |

| 2016 | 70%: Detached house, apartment house, type 1 and type 2 neighborhood living facility, cultural and congregational facility, religious facility, sales facility, transportation facility, sports facility, office facility, warehouse facility, and automobile-related facility |

In relation to the obligation to install an attached parking lot for NPFs, the process of changing the parking lot laws was investigated [33]. In 1995, when an attached parking lot was installed in the POB, it was amended to acquire the ownership of the building [34]. In 1999, it was amended to arbitrarily install an attached parking lot for all NPFs [35]. In 2004, when NPFs were department stores, shopping centers, large stores among sales and business facilities, and movie theaters, exhibition halls, and wedding halls among cultural and congregational facilities, it was amended to install an attached parking lot [36]. The current legislation is the same.

3. Traffic Inducement Coefficient

In order to calculate the amount of traffic caused by NPFs permitted in a POB, the characteristics of the TIC according to the Urban Traffic Improvement Promotion Act were investigated. Through this, researchers intended to define the TIR to be used as a dependent variable. The TIC is a coefficient for calculating the traffic inducement charge under the Urban Traffic Improvement Promotion Act. It is a relative indicator that shows the degree of congestion load that generated traffic exerts throughout the entire urban area by facility use and region [37].The traffic inducement charge is an economic burden imposed on facilities that cause congestion in accordance with the principle of the causative factor to alleviate traffic congestion [38].

Its formula is as follows [39]:

Traffic inducementcharge = Total floor area of each floor of the facility × Unit charge × TIC

The TIC was first introduced in 1990 to calculate the traffic inducement charge, and at that time, the coefficient was classified into 19 facilities and four regions for a total of 76 items. The regional classification was broadly classified into Seoul Metropolitan City and other regions, which were then subdivided into downtown and outlying regions, respectively. In 1994, general restaurants were added to the facility use, adding a total of 80 classification systems. In 1996, the use of facilities was divided into 34 facilities and 4 regions, expanding to a total of 136 classification systems. In the regional division, there is no division between the city center and the suburbs, and cities are classified into four types according to the size of the population. The TIC is a relative number. Based on a city with a population of 500,000 or more and less than 1 million, the TIC of office facilities is 1. For other facilities, the TIC (0.47~5.56) is determined by reflecting the relative difference based on this value [37][40]. Bergman, D. investigated 127 ordinances to prepare a comprehensive parking standard report for 180 land uses, including airports, universities, post offices, and telecommunication facilities. Within each land use, the criteria vary from requiring the least amount of parking to the most [41].

References

- Eskandari, M.; Nookabadi, A.S. Off-street Parking Facility Location on Urban Transportation Network Considering Multiple Objectives: A Case Study of Isfahan (Iran). Transport 2018, 33, 1067–1078.

- The Korean Government’s PLAN to Alleviate Parking Problems and Develop Parking Culture (Announced on 24 September 2014). Available online: http://www.molit.go.kr/USR/NEWS/m_71/dtl.jsp?lcmspage=3&id=95074526 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- Woo-Won, C.; Woo-Hyun, Y. Mixed-use Development of Public Parking Lot with Public Housing in the Subway Station Area: Case Study of Outdoor Public Parking Site in Seoul, Korea. J. Urban Des. Inst. Korea Urban Des. 2018, 19, 69–82.

- Song, Y.; Shao, G.; Song, X.; Liu, Y.; Pan, L.; Ye, H. The Relationships between Urban Form and Urban Commuting: An Empirical Study in China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1150.

- Ye, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, K.; Wu, Q.; Su, Y. Low-Carbon Transportation Oriented Urban Spatial Structure: Theory, Model and Case Study. Sustainability 2018, 10, 19.

- Koning, R.D.; Tan, W.G.Z.; Nes, A.V. Assessing Spatial Configurations and Transport Energy Usage for Planning Sustainable Communities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8146.

- Nadeem, M.; Aziz, A.; Al-Rashid, M.A.; Tesorierez, G.; Asim, M.; Campisi, T. Scaling the Potential of Compact City Development: The Case of Lahore, Pakistan. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5257.

- Nes, A.V. Spatial Configurations and Walkability Potentials. Measuring Urban Compactness with Space Syntax. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5785.

- Kim, E.-J. Type Study According to the Usage of Parking Lot in Development Project: Focusing on Dongtan (1) Newtown. Master’s Thesis, University of Seoul, Seoul, Korea, 2018.

- Kang, E.-G. A Study on the Financial Feasibility of Parking-only Buildings in Public Parking Lots in Incheon City. Master’s Thesis, Incheon University, Incheon, Korea, 2011.

- Gyesan Residential Land Private Parking Tower Is a Public Project. Available online: http://www.incheonilbo.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=917420 (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Yun-Sang, L.; Tae-Kyun, K.; Wan-Hee, B.; Dong-Wook, O.; Seok-Gyu, L. To Promote Rational Supply of off-Street Parking Lots, A Study on Measures to Improve the Legal System: Targeting LH Business Districts; Korea Land and Housing Research Institute (LHI): Daejeon, Korea, 2015; Volume 51.

- The Adjudication of Korean Supreme Court for ‘The Installation of the Audi Maintenance Center in Naegok-dong POB’. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/precInfoP.do?precSeq=178635 (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Jin, H.-S. The Perception of Happy Rental Housing in Seoul and Analysis of Household Characteristics. J. Korean Hous. Assoc. 2018, 29, 43–50.

- Kim, H.-B. A Scheme for Developing Complex Transfer Center. Transp. Technol. Policy 2010, 7, 37–45.

- The Parking Lot Act Article 2 No. 11. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/Law/Parking Lot Act/(20210713,17900,20210112)/Article 2 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- The Parking Lot Act Enforcement Decree Article 1-2. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/Law/Enforcement Decree of Parking Lot Act/(20210713,31636,20210420)/Article 1-2 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- Herma POB Source. Available online: https://ggarchimap.gg.go.kr/archives/gg_building-presentday/07/57/2641/#img_2 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- The National Land Planning Act Article 2 No. 6 and No. 13. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/Acts/Land Planning and Utilization Act/(20220113,17893,20210112)/Article 2 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- The Enforcement Decree of the National Land Planning Act Article 4. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/Law/Enforcement Decree of National Land Planning and Utilization Act/(20220218,32447,20220217)/Article 4 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- The Enforcement Decree of the Parking Lot Act Article 6 Paragraph 1 and Attached Table 1. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/Law/Enforcement Decree of Parking Lot Act/(20210713,31636,20210420)/Article 6 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- The Parking Lot Act Article 12-2. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/Law/Parking Lot Act/(20210713,17900,20210112)/Article 12-2 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- First Enactment of the Parking Lot Act. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/Law/Parking Lot Act/(03165,19790417) (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- The Parking Lot Act Amended on 31 December 1983. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/Law/Parking Lot Act/(03708,19831231) (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- The Parking Lot Act Amended on 14 December 1991. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/Law/Parking Lot Act/(04437,19911214) (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- The Enforcement Decree of the Parking Lot Act Amended on 30 June 1992. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/Law/Enforcement Decree of Parking Lot Act/(19920701,13672,19920630)/Article 1-22 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- The Enforcement Decree of the Parking Lot Act Amended on 18 February 1995. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/Law/Enforcement Decree of Parking Lot Act/(19950218,14530,19950218)/Article 1-22 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- The Enforcement Decree of the Parking Lot Act Amended on 4 June 1996. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/Law/Enforcement Decree of Parking Lot Act/(19960630,15017,19960604)/Article 1-2 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- The Enforcement Decree of the Parking Lot Act Amended on 30 June 1999. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/Law/Enforcement Decree of Parking Lot Act/(19990630,16428,19990630)/Article 1-2 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- The Enforcement Decree of the Parking Lot Act Amended on 20 December 2007. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/Act/Enforcement Decree of Parking Lot Act/(20080101,20459,20071220)/Article 1-2 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- The Enforcement Decree of the Parking Lot Act Amended on 30 December 2014. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/Law/Enforcement Decree of Parking Lot Act/(20141230,25935,20141230)/Article 1-2 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- The Enforcement Decree of the Parking Lot Act Amended on 19 January 2016. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/Law/Enforcement Decree of Parking Lot Act/(20160119,26911,20160119)/Article 1-2 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- Kim, M.-B. A Study on the Change Process and System Improvement Direction of Parking-only Buildings in New Town Housing Site Development Districts after 1990. Master’s Thesis, Hanyang University, Seoul, Korea, 2007.

- The Enforcement Decree of the Parking Lot Act Article 6 Paragraph 1 and Attached Table 1 Amended on 18 February 1995. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/Law/Enforcement Decree of Parking Lot Act/(19950218,14530,19950218)/Article 6 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- The Enforcement Decree of the Parking Lot Act Article 6 Paragraph 1 and Attached Table 1 Amended on 30 June 1999. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/Law/Enforcement Decree of Parking Lot Act/(19990630,16428,19990630)/Article 6 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- The Enforcement Decree of the Parking Lot Act Article 6 Paragraph 1 and Attached Table 1 Amended on 29 June 2004. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/Law/Enforcement Decree of Parking Lot Act/(20040701,18467,20040629)/Article 6 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- Korea Transport Institute. The National Transportation Survey and DB Construction Project: Transportation Inducement Unit Analysis Study; Korea Transport Institute: Seoul, Korea, 2013; pp. 18–20.

- The Definition of Traffic Inducement Levy According to the Urban Traffic Improvement Promotion Act Article 2, No. 9. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/Laws/Urban Traffic Improvement Promotion Act/(20210706,17871,20210105)/Article 2 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- The Calculation of Traffic Inducement Charges According to the Urban Traffic Improvement Promotion Act Article 37. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/Law/Urban Traffic Improvement Promotion Act/(20210706,17871,20210105)/Article 37 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- TIC by Facility According to the Enforcement Rule of the Urban Traffic Improvement Promotion Act Article 3-3 and Attached Table 4. Available online: https://www.law.go.kr/Laws/Enforcement Rules of the Urban Traffic Improvement Promotion Act/(20210827,00882,20210827)/Article 3-3 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- Bergman, D. Off-Street Parking Requirements; American Planning Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 1991.

More

Information

Subjects:

Regional & Urban Planning

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

749

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

28 Apr 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No