Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Byungjin Kim | -- | 1500 | 2022-04-25 08:13:43 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | -12 word(s) | 1488 | 2022-04-26 04:01:50 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Kim, B.; , . Structure of Miruk-Jõn Hall Kumsan-Sa Temple in Korean. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22221 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Kim B, . Structure of Miruk-Jõn Hall Kumsan-Sa Temple in Korean. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22221. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Kim, Byungjin, . "Structure of Miruk-Jõn Hall Kumsan-Sa Temple in Korean" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22221 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Kim, B., & , . (2022, April 25). Structure of Miruk-Jõn Hall Kumsan-Sa Temple in Korean. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22221

Kim, Byungjin and . "Structure of Miruk-Jõn Hall Kumsan-Sa Temple in Korean." Encyclopedia. Web. 25 April, 2022.

Copy Citation

The Miruk-jõn Hall of Kumsan-sa Temple (reconstructed in 1635, National Treasure No. 62) is in Gimje-si, Jeollabuk-do in the southern region of Korea. The Miruk-jõn Hall is a pagoda hall with a diminished structure, and the interior is thought to have been built in an ancient style. Miruk-jõn is a three-storied building, and the pillar spacing is five ken (2) (bays) for the first story, five ken for the second story, and three ken for the third story. In the second story, both Hatamas (the last interval between pillars) are narrowed.

Kiwari

Korean traditional building

temple architecture

construction scale

1. Introduction

South Korea and Japan, both located in East Asia, constructed wooden buildings that had many similarities, owing to their interactions with China in ancient times. In particular, their temple architecture incorporated these similarities and developed different characteristics over the ages, leading up to what we see now. These changes possibly occurred because of the development of elaborate structural systems and design techniques, while the overall external form, that is, the shape of the roof and the way in which the wooden structure transmits load, was maintained.

2. Miruk-Jõn Hall Kumsan-Sa Temple

Miruk-jõn is a three-storied building, and the pillar spacing is five ken (2) (bays) for the first story, five ken for the second story, and three ken for the third story. In the second story, both Hatamas (the last interval between pillars) are narrowed. The last interval between pillars is narrower in the two-tiered structure, and the question arises as to what the standard was for the five- and three-ken structures at the time of planning. It is particularly difficult to grasp the relationship between the dimensions of the building components, because the first and second layers of the five front pillars and the third layer of the three front pillars are planned as a single unit without breaking.

In Korea, the minimum standard size for a Buddhist temple is three ken (bays) at the front and three ken at the side (three ken × three ken), and there are a few five ken × five ken and seven ken × seven ken buildings. In the case of buildings larger than three ken × three ken, there are many buildings with different pillar spacings for the front and sides (five ken × four ken, five ken × three ken, seven ken × five ken, seven ken × three ken). This may be because in the Taung-jõn Hall (Buddhist temple) in Korea, the front of the building is more important than the sides, so the scale of the front is larger than that of the sides. This is perhaps because the principle of the ancient Chinese pillar configuration of “Moya” (the central space under the main roof of the hall)– “Hisasi” (eaves), described in the so-called “Kenmenkihou” technique, was followed in Korea even after the Middle Ages. Moreover, the front five-bay configuration is a three-bay four-sided hall consisting of a Moya with four sides and Hisasi, but the two sides of the core bay have side bays that are too narrow for the core bay, and nearly all the side ends become Hisasi, in which case the three bays consisting of a core bay and side bay become the building’s Moya [1][2][3][4][5].

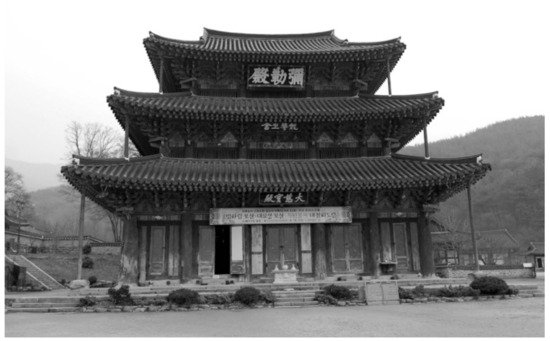

The Miruk-jõn Hall of Kumsan-sa Temple (reconstructed in 1635, National Treasure No. 62) is in Gimje-si, Jeollabuk-do in the southern region of Korea (Figure 1). The Miruk-jõn Hall is a unique, three-story Buddhist temple. The history of the building can be found in the records of “Jinpyojyonganzo (眞表傳簡條)” and “Kandongpungakbalyonsusokkizo (關東楓岳鉢淵藪石記條)” in the documents on the Miruk-jõn Hall, “Kumsan-sa Temple magazine (金山寺誌)”, and “The Heritage of the Three States (三國遺事)” (4). In each of these records, there are references to the Miruk-jõn Hall in the first year of Baekje’s reign (Baekje BubWang: 599), but it is unclear when exactly the hall was built. It is known that the building was destroyed by fire in 1597; reconstructed in 1635; repaired in 1748, 1897, 1926, 1938, and 1962; and that the roof frame was dismantled and repaired in 1975. The building has a tablet inscribed with Dejabozon (大慈寶殿) on the first story, Yongwhajioe (龍華之會) on the second story, and Miruk-jõn (彌勒殿) on the third story. All of these mean “World of Buddha” (Buddha’s doctrine).

Figure 1. Miruk-jõn Hall, Kumsan-sa Temple.

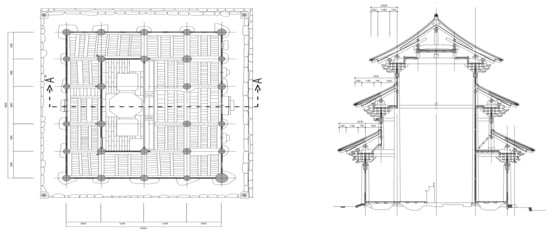

Figure 2 shows that the Miruk-jõn Hal is not a pagoda structure with a Shinbashira (the central pillar of a pagoda) at the center of the building, but is a hall structure, including the roof style. In Korea, the styles distinguished by the entablature are Dapo (Tumegumi: A complex bracket style which is both on top of each pillar and in between pillars) and Jusimpo (Amagumi: A bracket situated directly above a pillar).

Figure 2. Floor plan and A–A cross-section of Miruk-jõn Hall [6].

First story: pillars are round, untreated natural wood pillars.

Second story: pillars are round, standing on a beam (Tunagibari: tie beam) that is connected to a pillar (Tukahasira: short pillar standing between the beam and the ridge).

Third story: the pillar is also round, with one to three through-pillars. For the sake of convenience, it refers to these through-pillars as triple pillars.

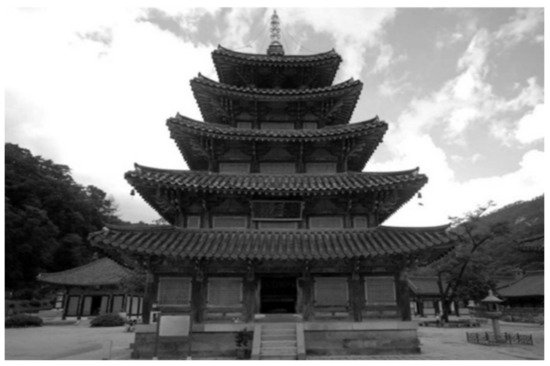

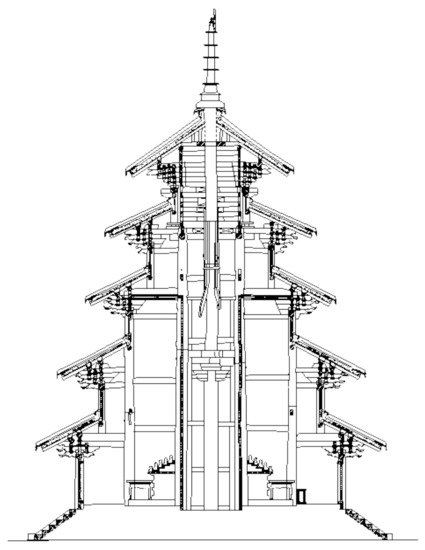

Among the major Buddhist temples in Korea, the two buildings with more than three stories are the Miruk-jõn Hall and the Palsang-jðn Hall of the Beopjusa Temple (a five-story hall rebuilt in 1626, National Treasure No. 55). The latter has a Sorin (a metal pinnacle) of a pagoda on the roof, a Shitenbashira (four pillars placed around a Buddhist altar), and a Shinbashira (the central pillar of a pagoda), as shown in Figure 3, suggesting that the building was converted from a pagoda to a hall (Figure 4). The cross-sectional structure shows that the three-story pillars are Irigawahasira (pillar of the sanctum of a temple) and the five-story pillars are through-pillars (the four heavenly pillars) of the Shinbashira, and each story is narrower by a half. Since the structure of this building, which creates a degression up to the third story, is similar to that of the Miruk-jõn Hall, it is possible to suppose that the similar part of Miruk-jõn was changed from a structure up to the third story of the five-story pagoda. There are no wooden pagodas in Korea, but there are stone pagodas.

Figure 3. Palsang-jðn Hall, Beopjusa Temple.

Figure 4. A–A cross-section of Palsang-jðn Hall, Beopjusa Temple [7] (6).

Analysis of the Decreasing Rate

With respect to the tapering of the building, the Palsang-jðn Hall of Beopjusa and the Miruk-jõn Hall, which have the appearance (tapering) of a pagoda, are built with a short pillar standing between a beam and roof ridge and eaves. A Tukahasira (short pillar standing between a beam and roof ridge) on top of a Tunagibari (a beam and a roof ridge), or the method of narrowing each layer by half, is characteristic of Korean multistory buildings, and there are no buildings with the same structure in China or Japan. The Dulesi Guanyinge (China), the Fogongsi Shijiata (China), and the five-storied Pagoda Houryuji (Japan) have distinct floors, while the Korean Miruk-jõn Hall and the Palsang-jaðn Hall of Beopjusa are multistory constructions (having a continuous integral construction system) without floors.

However, the Korean continuous integral construction system is a structure that partially exists in Japan; for example, Gondo Hudoin. In China too, there is Chanzhuzao in 『営造法式 (Yingzao Fashi)』, which has a similar structure to that of the Miruk-jõn Hall, though there is no actual structure that exists. This is perhaps because the techniques did not emerge in the Middle Ages in Korea but have existed since ancient times.

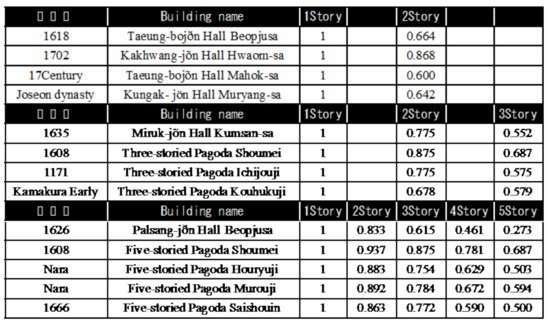

Based on the diminishing rate of the Palsang-jðn Hall and Miruk-jõn Hall, it is evident that they are similar to Japanese pagodas (five-storied pagodas, three-storied pagoda). The numerical values of the total interstable dimensions of the first, second, and third stories of the Shomei (匠明三重塔) three-storied pagoda correspond to the numerical value of the first, third, and fifth stories of the five-storied pagoda (Figure 5) (7). From Figure 5, it is evident that the three-storied Miruk-jõn Hall is similar to the three-storied Ichijouji pagoda and the five-storied Saishouin pagoda (the three- and five-story parts).

Compared to Japanese pagodas, the difference between the two becomes greater from the third story onward, and the Palsang-jðn Hall, Beopjusa, shows an elevation plane with a high rate of tapering. In the case of the two-story halls, the rate of tapering is generally high, with only the Kakhwang-jõn Hall, Hwaom-sa, being slower and closer to the rate of tapering of the Shomei pagoda.

The Miruk-jõn Hall is a pagoda hall with a diminished structure, and the interior is thought to have been built in an ancient style. It is assumed that the pagoda was built before the transformation from a five-story pagoda to a three-story pagoda and then to a two-story pagoda (the roof style and other features were changed, but the structural form remained the same).

References

- Ito, N. Study on the Wayo Architecture in the Middle Ages of Japan; Shokokusha: Tokyo, Japan, 1961.

- Sekiguchi, K. The Interior of ZEN Style, Its Cross Section and the Influence on Japanese Traditional Style (1). J. Archit. Inst. Jpn 1966, 120, 60–87.

- Sekiguchi, K. The Interior of ZEN Style, Its Cross Section and the Influence on Japanese Traditional Style (2). J. Archit. Inst. Jpn. 1966, 123, 55–75.

- Sekiguchi, K. On the Distribution of Bays in ZEN STYLE (1). J. Archit. Inst. Jpn. 1965, Volume 115, 44–51.

- Sekiguchi, K. On the Distribution of Bays in ZEN STYLE (2). J. Archit. Inst. Jpn. 1965, Volume 116, 58–65.

- Cultural Heritage Administration. Miruk-Jõn Hall Kumsan-Sa Temple Survey Report; Cultural Heritage Administration: Daejeon, Korea, 2001.

- Cultural Heritage Administration. Palsang-Jðn Hall Beopjusa Temple Survey Report; Cultural Heritage Administration: Daejeon, Korea, 2013.

- Cultural Heritage Administration. Kakhwang-Jõn Hall Hwaom-Sa Temple Survey Report; Cultural Heritage Administration: Daejeon, Korea, 2009.

- Cultural Heritage Administration. Geungnakjeon Hall Muryangsa Temple Survey Report; Cultural Heritage Administration: Daejeon, Korea, 2011.

- Cultural Heritage Administration. Taeung-Bojðn Hall Beopjusa Temple Survey Report; Cultural Heritage Administration: Daejeon, Korea, 2005.

- Cultural Heritage Administration. Taeung-Bojõn Hall Mahok-Sa Temple Survey Report; Cultural Heritage Administration: Daejeon, Korea, 2012.

- Takeshima, T. Plane composition of Horyuji Five storied Pagoda. Tokai Branch Res. Rep. Collect. 1964, 3, 39–45.

- Sekino, T. Golden Hall, Toba, Inner gate of Horyu-ji Temple no reconstruction theory. J. Archit. Build. Sci. 1905, 218, 67–82.

- Hamasima, M. Pagoda Collection in Japan; Central Public Arts Publishing: Tokyo, Japan, 2001.

More

Information

Subjects:

Construction & Building Technology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.8K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

26 Apr 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No