Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Javier Gomez-Ambrosi | -- | 1999 | 2022-04-21 10:08:15 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | -5 word(s) | 1994 | 2022-04-21 10:33:25 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Gomez-Ambrosi, J.; Catalán, V.; Aviles-Olmos, I.; Rodríguez, A.; Becerril, S.; , .; Kiortsis, D.; Portincasa, P.; Frühbeck, G. Exposome Hypothesis in Obesity Pandemic. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22080 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Gomez-Ambrosi J, Catalán V, Aviles-Olmos I, Rodríguez A, Becerril S, , et al. Exposome Hypothesis in Obesity Pandemic. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22080. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Gomez-Ambrosi, Javier, Victoria Catalán, Iciar Aviles-Olmos, Amaia Rodríguez, Sara Becerril, , Dimitris Kiortsis, Piero Portincasa, Gema Frühbeck. "Exposome Hypothesis in Obesity Pandemic" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22080 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Gomez-Ambrosi, J., Catalán, V., Aviles-Olmos, I., Rodríguez, A., Becerril, S., , ., Kiortsis, D., Portincasa, P., & Frühbeck, G. (2022, April 21). Exposome Hypothesis in Obesity Pandemic. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/22080

Gomez-Ambrosi, Javier, et al. "Exposome Hypothesis in Obesity Pandemic." Encyclopedia. Web. 21 April, 2022.

Copy Citation

The obesity epidemic shows no signs of abatement. Genetics and overnutrition together with a dramatic decline in physical activity are the alleged main causes for this pandemic. While they undoubtedly represent the main contributors to the obesity problem, they are not able to fully explain all cases and current trends. A body of knowledge related to exposure to as yet underappreciated obesogenic factors, which can be referred to as the “exposome”, merits detailed analysis. Contrarily to the genome, the “exposome” is subject to a great dynamism and variability, which unfolds throughout the individual’s lifetime.

obesogens

“exposome”

environment

epigenetics

microbiota

1. Introduction

If practitioners are asked about the current key public health challenges, in addition to the COVID-19 pandemic, many will mention obesity among the top priorities. The prevalence of obesity has tripled during the last decades, imposing an enormous burden not only on people’s health, but also on society at large with obesity increasing worldwide [1][2][3]. Risk factor exposure, relative risk, and imputable disease burden have been addressed in a comprehensive and standardized way by the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study [4]. A rigorous analysis of the trends and specific levels of risk factor exposure together with a quantitative assessment of the plausible human health effects is of utmost importance. In this context, deep knowledge is required about when current efforts are being inadequate as opposed to when public health initiatives are showing fruitful effects. Identifying the ecological factors and external drivers of change that are currently tipping the balance may prove extraordinarily useful. This approach represents a biomedical challenge and public health need. Thus, it is worthwhile considering the conceptual basis to better understand alterations at the population level as well as their potential interaction with the surrounding with an innovative perspective on, as yet, underappreciated but conceivable factors. A search for original articles and reviews published between January 1990 and February 2022 focusing on causes and contributors was performed in PubMed and MEDLINE using the following search terms (or combination of terms): “obesity”, “epidemic or pandemic”, “comorbidity or comorbidities”, “outcomes”, “mortality”, “drivers”, “sedentarism”, “physical inactivity”, “environment or environmental”, “antibiotics”, “microbiota”, “genetics”, “epigenetics”, “viral infection”, “infectobesity”, “sleep”, “chronobiology”, “obesogens”, “endocrine disrupters”, “thermogenesis”, “urban planning”, “climate change” and “exposome”. Only English-language, full-text articles were included. Additional articles that were identified from the bibliographies of the retrieved articles were also used, as well as selected very recent references from March 2022. Articles in journals with explicit policies governing conflicts-of-interest, and stringent peer-review processes were favored. Data from larger replicated studies with longer periods of observation, when possible, were systematically chosen to be presented. More weight was given to randomized controlled trials, prospective case–control studies, meta-analyses and systematic reviews.

Up-to-date the thinking on the obesity epidemic has focused mainly on direct causes, such as genetic and behavioral determinants of energy intake and expenditure [5][6]. The combination of increased sedentarism and life expectancy have contributed to the obesity epidemic and its comorbidities with people exhibiting a poorer physical function [7][8][9]. Exercise produces extraordinarily complex physiological responses at the same time as inducing changes in cellular energy balance, leading to intensity-dependent activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in skeletal muscle [7][10], via effects on diverse intramuscular and hormonal factors adaptations to increased physical activity include amelioration of the cardiorespiratory fitness, as shown by an augmented maximal oxygen uptake together with an elevated muscle oxidative capacity promoted by an increased mitochondrial biogenesis and angiogenesis. Elicited signals include enhanced catecholamine signaling, sarcoplasmic calcium release, changes in mechanical stretch and force, metabolic alterations, disruptions to the redox state and acid–base balance, increased muscle temperature, and increased circulating adrenaline concentrations. These signals operate on transmembrane receptors, thereby activating downstream signaling pathways, or directly stimulate the release of exercise-responsive signaling molecules. Interestingly, exercise stimulates the secretion of metabolites, extracellular vesicles, and myokines that enable crosstalk with other organs, like adipose tissue, pancreas, liver, heart, gut, and brain as well as the vascular and immune systems.

When focusing on the time scale, two quite diverse influences can be distinguished that exert their effects on ingestive behavior, as well as on other aspects of energy homeostasis [11]. The evolutionary time frame, on the one hand, determines the selection of metabolic and behavioral traits embedded within a concrete genome. Famine, as a continuous peril to survival, has led to the selection of the so-called “thrifty genes”. Within a given environmental context, this thriftiness can be manifested at different levels, such as (i) the ‘energy-sparing’ metabolism to increase efficiency (metabolic), (ii) the proclivity to quick adipose tissue accretion (adipogenic), (iii) the capability to slow down or even switch off non-essential processes (physiologic), (iv) the propensity to hastily swallow available food (gluttony), (v) the proneness towards sedentarism to spare or conserve energy (sloth), and, finally, (vi) behavioural adaptations that can even result in selfish hoarding to warrant survival (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the factors involved in energy homeostasis. The classical Venn diagram shows how in obesity the intersection between increased food intake, nutrient absorption, and fat accumulation, together with decreased energy expenditure, the main factors determining energy homeostasis, are simultaneously under the broader influence of the environment as well as genetics and epigenetics.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the factors involved in energy homeostasis. The classical Venn diagram shows how in obesity the intersection between increased food intake, nutrient absorption, and fat accumulation, together with decreased energy expenditure, the main factors determining energy homeostasis, are simultaneously under the broader influence of the environment as well as genetics and epigenetics.2. The “Exposome” as a Plausible Underlying Mechanism of Action

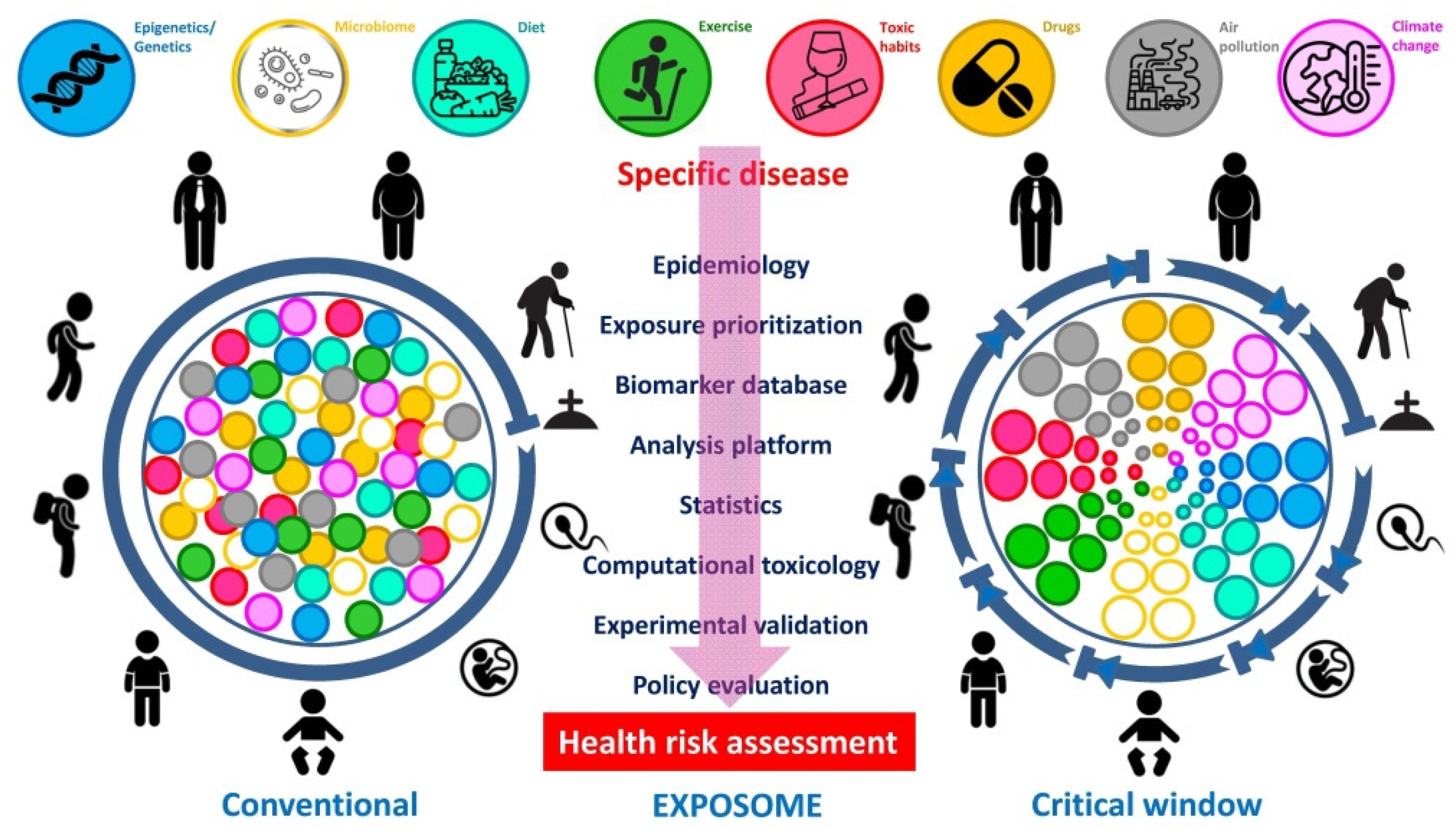

The word “exposome” stands for the assessment over the whole life of a person of all the exposures and its relationship to disease. This concept has been fostered by the success in mapping the human genome [12][13]. Of note, the exposure of a person starts at conception and in utero, continuing over childhood and adolescence (Figure 2). Job-related insults as well as influences from leisure time and the environment further accumulate during adulthood progressing up to senescence. Many single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are genetic variants of low penetrance involved in the control of food intake, body weight, and lipid metabolism, among others.

Figure 2. Conventional versus critical window “exposome” views in assessment of health risk in humans. The comprehensive portrait of an individual’s “exposome” evolves throughout the lifetime with the possibility of prioritized exposure factors, during specific time-points or critical windows as opposed to a standard, random or linear exposure. The diagram emphasizes the relevance of measurements at different time-points (modified from Fang et al. [14]).

Figure 2. Conventional versus critical window “exposome” views in assessment of health risk in humans. The comprehensive portrait of an individual’s “exposome” evolves throughout the lifetime with the possibility of prioritized exposure factors, during specific time-points or critical windows as opposed to a standard, random or linear exposure. The diagram emphasizes the relevance of measurements at different time-points (modified from Fang et al. [14]).Despite their low penetrance, the SNPs’ high prevalence implies a potential substantial contribution to the disease burden at the population level. This means that in a concrete exposure scenario the majority of SNPs, although being of low penetrance, will emerge because of strong environmental influences. While exposures of the surrounding exhibit an exceedingly relevant protagonism in the development of NCDs, a clear association is not easy to unravel. The “exposome” will be best deciphered by obtaining deeper knowledge on how dietary and lifestyle exposures interplay with the individual’s unique genetic, epigenetic, and physiologic characteristics translate into disease. In this scenario, the “exposome” can be contemplated from a conventional point of view, in which insults are randomly distributed along the whole lifecycle, or with the lens of the critical window exposure, in which insults are non-randomly allocated to specific time-periods during life [14]. Improvement in disease etiology identification at the population level will come from complementing the emphasis on genotyping by a detailed analysis of the plentiful environmental exposures [15][16], with its accurate assessment remaining a formidable and pending demand in obesity assessment. Moreover, the development of methods that accurately capture both the external environment as well as the internal chemical background of the individual are urgently needed (Figure 3). In order to complement the “genome” with its matching “exposome” the same precision for an individual’s environmental exposure for the subject’s genome which should be pursued.

Figure 3. Characterization of the “exposome”. The “exposome” of a given person represents the combined exposures from all external sources that reach the internal chemical environment. Specific biomarkers or potential signatures of the “exposome” might be detected in the bloodstream.

Figure 3. Characterization of the “exposome”. The “exposome” of a given person represents the combined exposures from all external sources that reach the internal chemical environment. Specific biomarkers or potential signatures of the “exposome” might be detected in the bloodstream.2.1. Need for an Integral Consideration of the Collective Impact of Simultaneously Acting Drivers

Contrarily to the genome, the “exposome” is subject to a great dynamism and variability, which unfolds throughout the individual’s lifetime. The development of precise ways of determination that capture the full exposure spectrum of a person is extraordinarily demanding. These considerations are particularly relevant for children and adolescents with obesity, given that the increased exposure is expected to translate into larger adverse effects than weight gain only during adulthood [17][18]. Furthermore, the concept of epigenetics comprises the study of changes in the organism caused by alterations in gene expression rather than modifications of the genetic code itself [19][20]. Interestingly, epigenetic marks can be affected by air pollution, organic pollutants, exposure to benzene, metals, and electromagnetic radiation. Other potential environmental stressors capable of changing the epigenetic landscape include chemical and xenobiotic compounds present in the atmosphere or water.

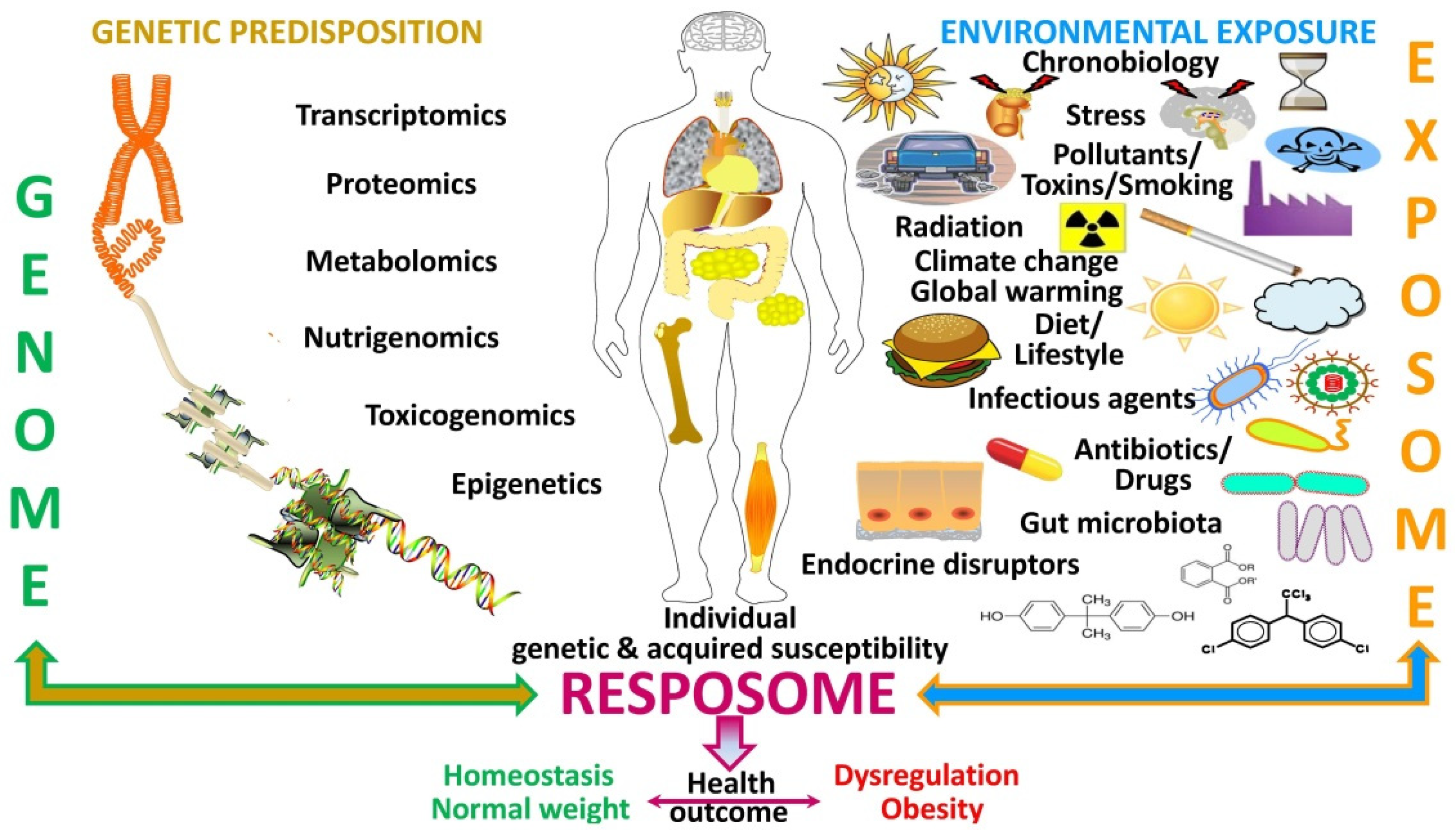

Moreover, while responses to certain specific exposures are invariable, to other external insults responses may change (“resposome”), with disparity depending on genome and epigenome changes (Figure 4). While some alterations reveal chronicity in exposure, certain cases reveal a latent response, based on “priming” for a late pathogenesis via epigenetic changes.

Figure 4. Factors influencing the resposome. Schematic diagram on how the genetic predisposition (genome) interacts with the environmental exposure (“exposome”) to influence an individual’s genetic and acquired susceptibility shaping its responses (resposome) that yield the ultimate health outcome as regards body weight control.

Figure 4. Factors influencing the resposome. Schematic diagram on how the genetic predisposition (genome) interacts with the environmental exposure (“exposome”) to influence an individual’s genetic and acquired susceptibility shaping its responses (resposome) that yield the ultimate health outcome as regards body weight control.Analysis of the current human “exposome” emphasizes the challenges represented by the concepts of lifelong exposure and the need to compute all environmental factors in order to obtain the whole real life exposomic scenario [14]. To overcome these limitations and establish the relation between human health and the “exposome” focusing on critical-window periods can be combined with data- and hypothesis-driven exposomics. Moreover, analysis of high-throughput and multidimensional data of both internal and external exposure factors are welcome [14]. Useful tools to analyze the “exposome” and foster exposomics should comprise different steps, i.e., (i) the development of biomarkers capturing exposure effect, susceptibility to exposure, and disease progression; (ii) the application of advances that integrate systems biology with environmental big data; and (iii) exploratory data mining to analyze the relationships between exposure effects, and other factors that ultimately lead to obesity development and thereby provide potential mechanistic information (Figure 5). Artificial intelligence will broadly reshape medicine, thereby improving the experiences of both patients and clinicians. In fact, artificial intelligence is already being applied in an ever-increasing number of medical fields moving from what might have been considered speculation years ago to reality right now. Progress in data analysis, including image deconvolutions, non-image data sources, unconventional problem formulations, sophisticated algorithms, and human–artificial intelligence collaborations, will reduce the gap between research and clinical practice. While these challenges are being addressed, artificial intelligence will develop exponentially, making healthcare more accessible, efficient, and accurate for patients worldwide [21].

Figure 5. Evolution of the individual’s genetic and environmental framework across the lifespan. Over a lifetime, genetic and environmental influences may change reciprocally with acute and chronic exposures translating into a specific information with predictive interest as well as effective biomarkers that may provide mechanistic insight of pragmatic application.

Figure 5. Evolution of the individual’s genetic and environmental framework across the lifespan. Over a lifetime, genetic and environmental influences may change reciprocally with acute and chronic exposures translating into a specific information with predictive interest as well as effective biomarkers that may provide mechanistic insight of pragmatic application.In order to be particularly helpful, “exposome” assessment should combine GWAS together with epigenome-wide association trials and detailed metabolic-endocrinological phenotyping of the individuals. Moreover, these combined analyses should be applied at multiple time-points to establish the potential interaction effect. The large amount of data on exposures provided by these projects hinders the interpretation of their relationship with health outcomes and omics. In this regard, similar or parallel databases to genetics (OMIN, dbSNP, or TCGA) may be developed for exposomics. Together with handling and archiving large data volumes, the lack of standard nomenclature, the quality of output from each analytical platform, or the heterogeneity of data constitute important issues to be resolved. Given the important public health problem posed by the rise in NCDs like obesity, the presented proposal of integration of elements that constitute the “exposome” will strengthen the better comprehension of the intricate underlying mechanisms, thereby opening pathways to innovative preventive and therapeutic strategies.

References

- Finucane, M.M.; Stevens, G.A.; Cowan, M.J.; Danaei, G.; Lin, J.K.; Paciorek, C.J.; Singh, G.M.; Gutierrez, H.R.; Lu, Y.; Bahalim, A.N.; et al. National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: Systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9.1 million participants. Lancet 2011, 377, 557–567.

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128.9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2017, 390, 2627–2642.

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration. Rising rural body-mass index is the main driver of the global obesity epidemic in adults. Nature 2019, 569, 260–264.

- Collaborators, G.R.F. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1223–1249.

- Hill, J.O. Understanding and addressing the epidemic of obesity: An energy balance perspective. Endocr. Rev. 2006, 27, 750–761.

- Loos, R.J.F.; Yeo, G.S.H. The genetics of obesity: From discovery to biology. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 120–133.

- McGee, S.L.; Hargreaves, M. Exercise adaptations: Molecular mechanisms and potential targets for therapeutic benefit. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2020, 16, 495–505.

- Dixon, B.N.; Ugwoaba, U.A.; Brockmann, A.N.; Ross, K.M. Associations between the built environment and dietary intake, physical activity, and obesity: A scoping review of reviews. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13171.

- Woessner, M.N.; Tacey, A.; Levinger-Limor, A.; Parker, A.G.; Levinger, P.; Levinger, I. The evolution of technology and physical inactivity: The good, the bad, and the way forward. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 655491.

- Rodríguez, A.; Becerril, S.; Ezquerro, S.; Méndez-Giménez, L.; Frühbeck, G. Crosstalk between adipokines and myokines in fat browning. Acta. Physiol. 2017, 219, 362–381.

- Prentice, A.M. Early influences on human energy regulation: Thrifty genotypes and thrifty phenotypes. Physiol. Behav. 2005, 86, 640–645.

- Rappaport, S.M.; Smith, M.T. Epidemiology. Environment and disease risks. Science 2010, 330, 460–461.

- Zhang, P.; Carlsten, C.; Chaleckis, R.; Hanhineva, K.; Huang, M.; Isobe, T.; Koistinen, V.M.; Meister, I.; Papazian, S.; Sdougkou, K.; et al. Defining the scope of exposome studies and research needs from a multidisciplinary perspective. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2021, 8, 839–852.

- Fang, M.; Hu, L.; Chen, D.; Guo, Y.; Liu, J.; Lan, C.; Gong, J.; Wang, B. Exposome in human health: Utopia or wonderland? Innovation 2021, 2, 100172.

- Wild, C.P. Complementing the genome with an "exposome": The outstanding challenge of environmental exposure measurement in molecular epidemiology. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarks Prev. 2005, 14, 1847–1850.

- Wild, C.P. The exposome: From concept to utility. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 41, 24–32.

- The, N.S.; Suchindran, C.; North, K.E.; Popkin, B.M.; Gordon-Larsen, P. Association of adolescent obesity with risk of severe obesity in adulthood. JAMA 2010, 304, 2042–2047.

- Golding, J.; Gregory, S.; Northstone, K.; Iles-Caven, Y.; Ellis, G.; Pembrey, M. Investigating possible trans/intergenerational associations with obesity in young adults using an exposome approach. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 314.

- Wu, Y.; Perng, W.; Peterson, K.E. Precision Nutrition and Childhood Obesity: A Scoping Review. Metabolites 2020, 10, 235.

- Mahmoud, A.M. An overview of epigenetics in obesity: The role of lifestyle and therapeutic interventions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1341.

- Rajpurkar, P.; Chen, E.; Banerjee, O.; Topol, E.J. AI in health and medicine. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 31–38.

More

Information

Subjects:

Nutrition & Dietetics

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.2K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

21 Apr 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No