Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Elvi Chang | -- | 2926 | 2022-04-20 10:22:45 | | | |

| 2 | Vivi Li | -2 word(s) | 2924 | 2022-04-21 05:30:09 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Chang, E.; , .; Rambaree, K. Youth Empowerment for Sustainable Development. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21991 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Chang E, , Rambaree K. Youth Empowerment for Sustainable Development. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21991. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Chang, Elvi, , Komalsingh Rambaree. "Youth Empowerment for Sustainable Development" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21991 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Chang, E., , ., & Rambaree, K. (2022, April 20). Youth Empowerment for Sustainable Development. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21991

Chang, Elvi, et al. "Youth Empowerment for Sustainable Development." Encyclopedia. Web. 20 April, 2022.

Copy Citation

Youth, generally defined as young people aged between 15 and 24, are a key population. Their empowerment as members of our societies is vital for the societal ecosocial transition from a human-centered to an ecosocial focus, in pursuit of Sustainable Development (SD) and the United Nations “The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” with its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In relation to sustainability, ecosocial transition is a holistic perspective with ecological, economic, and social dimensions of development focusing on the interlinkage between social and ecological sustainability.

youth empowerment

ecosocial work

sustainable development

Foucauldian discourse

1. Introduction

Youth, generally defined as young people aged between 15 and 24, are a key population. Their empowerment as members of societies is vital for the societal ecosocial transition from a human-centered to an ecosocial focus, in pursuit of Sustainable Development (SD) and the United Nations “The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” with its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In relation to sustainability, ecosocial transition is a holistic perspective with ecological, economic, and social dimensions of development focusing on the interlinkage between social and ecological sustainability [1]. From this perspective, it is argued that youth can create and become a positive and dynamic force for SD if they are given the knowledge and opportunities to thrive and be involved in decision-making processes [2]. Youth inclusion in decision-making processes for SD is therefore one of the key variables associated with youth empowerment.

Youth empowerment, and empowerment in general, occurs at individual and collective levels, in the form of, amongst others, psychological, social, economic and political empowerment. Rocha [3] presented empowerment as a ladder, with individual empowerment focusing on changing the individual (individual level), and political empowerment focusing on changing the community (collective level). Youth empowerment emphasizes youth strength instead of weaknesses. It enables and promotes greater active youth participation and influence in the settings in which they are involved and which affect their lives [4]. Variables associated with youth empowerment include “increased skills, critical awareness and mastery of the environment, higher levels of self-determination, shared decision-making, and participatory competence” [5] (p. 403). These variables can be observed in the movement initiated by the Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg, who in 2018 at the age of 15 started a protest outside the Swedish Parliament for stronger action on climate change with a sign reading “Skolstrejk för klimatet” (School Strike for Climate). This strike initiated the Fridays for Future movement, in which youth on school strike protested every Friday against the lack of professional and political responses towards climate actions. In particular, professionals such as social workers across the world are being blamed by climate-engaged groups of young people for not doing enough to secure their future in terms of SD [6].

In 1987, the World Commission on Environment and Development published a report, Our Common Future, including a now widely cited definition of SD as being “a development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [7] (p. 54). SD (references to SD inherently cover the SDGs, as the SDGs are the embodiment of SD) aims for a balanced, harmonious, and integrated set of goals that meet urgent environmental, social, and economic challenges by focusing on people, the planet, prosperity, peace, and partnership. Nevertheless, some have argued that SD and the SDGs are still very anthropocentric [8][9], though some SDGs can be interpreted as comprising biocentric or ecocentric aspects [8][9][10]. This means that these SDGs do recognize not only human values but the intrinsic value of all living beings [8]. SD ranges from eradicating poverty to promoting sustainable cities and communities [11]; it consists of interlinked goals relating to the dimensions of economic prosperity, environmental protection, and social equity; these are widely known as the “triple bottom line”, a notion coined by John Elkington in 1994 [12]. These three dimensions (sometimes referred to as elements) are widely acknowledged as the “three pillars” in discussions of SD.

In Sweden, as in many other countries, one way that young people learn about SD is through Lärande för Hållbar Utveckling (Education for Sustainable Development, ESD) in schools. ESD was developed to response the need for education to address sustainability challenges; at the 2019 UNESCO General Conference, the Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) for 2030 was adopted, which is a continuation of UNESCO’s four-year Global Action Program (GAP) for Education for Sustainable Development [13]. ESD is widely recognized as an integral component of The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, as well as a key enabler of all SDGs in achieving societal transformation towards a more sustainable society by emphasizing on education’s role for the SDGs, the focus on the transformation and member states’ leadership [14]. Although many of the SDGs are explicitly directed towards the wellbeing of young people, SD in general and youth engagement in SD in particular have not been major subjects of discussion in mainstream social work [15]; this is also the case in social work in Sweden, where the planetary focus on the ecosystem in relation to human wellbeing has only been marginally investigated [16][17], and few empirical studies have been conducted. Youth as community members are often seen as individuals who lack capacity and agency in comparison to adults, and thus they are rarely actively engaged as community members in decision-making and social change processes [18][19]. An extensive review of social work literature addressing environmental topics between 1991 and 2015 [20] found no title or abstract including the words “youth”, “young people” or “children”, indicating the marginal focus on the role of youth within this area. It is vital to engage and empower youth within the practice of social work, as they are the future agents of change, particularly concerning changes towards SD. In this connection, youth empowerment within the ecosocial transition towards SD needs to gain more attention within social work, both internationally and in Sweden. In this context, some authors have pointed out the need to involve and empower young people in SD work, which amongst other has been amplified by global calls being made to social workers in engaging key partners such as the youth in SD through ecosocial work [21][22].

The concept of an “ecosocial” approach is still fuzzy, ranging from human harmony with nature to a philosophical paradigm of the human position in a “person-in-environment” perspective. Different organizations with different priorities and backgrounds use different definitions of the term. Within social work, the ecosocial approach is one way to address socio-ecological crises and societal transition towards sustainability. Ecosocial work is understood as emancipatory and political [19][23], as it calls upon social workers to act collectively with community members to support social and economic equality, human dignity, ecological sustainability, and collective wellbeing [24][25]. Ecosocial work recognizes the interrelation and interdependency between the wellbeing of the Earth and its inhabitants [26], taking into consideration the broader biophysical aspects (including the biotic, abiotic, natural, and built environments) and social environment in a way that conjoins social, ecological, cultural, and economic sustainability [23][24][27]. Ecosocial work also challenges the modernist view of the place of humans in the natural world [26], which has been taken for granted; thus, ecosocial work adapts the philosophy of post-anthropocentricism by decentering the position of humans in the natural world.

The anthropocentric view is commonly dualistic and binary, with humans considered to be masters above “the other” and “outside” the ecosystem [21], and nature considered to be at the service of fulfilling human needs. Post-modernist social work is challenged with socio-ecological crises, leading to discussions of the need for a paradigm shift from anthropocentrism to a more ecocentric perspective in viewing the relations between human/nature and human/animals [21][28][29][30][31]. Social work and societies at large are therefore required to decenter human exceptionalism by extending “rights” to non-humans [10] in order to address contemporary socio-ecological challenges [26]. There is a need for a “post-anthropocentric turn” in social work [31] by rejecting the twin ideas of human supremacy and human exceptionalism [32].

2. Conceptual and Theoretical Framework

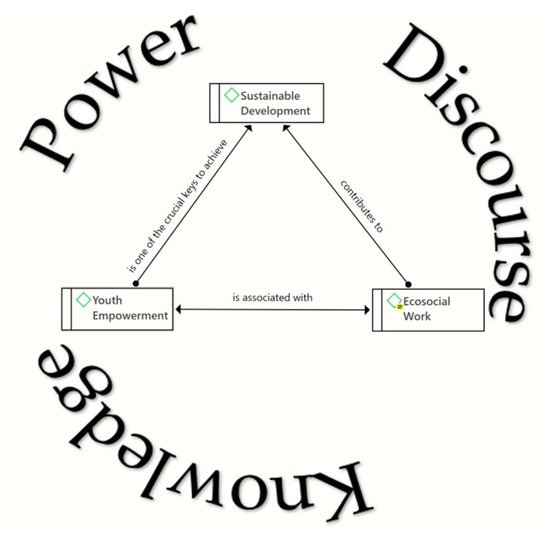

A theoretical and conceptual framework (Figure 1) was developed on the basis of existing literature and used in conducting this entry. An abductive approach was chosen in which the framework guided the data generation and the gathered data were explored with reference to the framework, moving back and forth between the framework and data during the analytical process [33]. The conceptualization and theorization therefore provided a basis for exploring and understanding ecosocial work discourse and youth empowerment within the context of SD. A narrative explanation including the reasoning behind this framework is given below.

Figure 1. Theoretical and conceptual framework based on Foucauldian discourse analysis.

Empowerment is a central concept within social work, particularly in enhancing the wellbeing and strength of all people by engaging individuals and structures in addressing life and societal challenges [34]. Empowerment in social work refers to both the desired state of being empowered through interventions, and the intervention method itself in improving wellbeing; it is multidimensional and multifaceted, but is often defined as having the means to control one’s life situation in achieving personal and societal goals [35]. The concept empowerment is connected to individual and collective health, wellbeing and environments [36][37][38][39][40]; it is also understood as a social action process in which community members have, assume, or expand their power and responsibility in creating desired societal changes [41]. This means empowerment occurs at different and multiple levels, such as individual, family, organization, and community/collective [37][42]

Individual empowerment is empowerment on psychological, individual case work levels [43] stressing individual capacity-building, personal control, a positive life view, and may also include a comprehension of the sociopolitical environment [44][45]. In this relation, the adults working with youth empowerment and sociopolitical learning experiences has empowering role in “challenging deficit assumptions of youth political capabilities” [46] (p. 53). On the other side, collective empowerment is on group, social, political, and structural levels [43] focusing on sociopolitical and political empowerment [3] involving “processes and structures that enhance members’ skills, provide them with mutual support necessary to effect change, improve their collective wellbeing, and strengthen intra- and inter-organizational networks and linkages to improve or maintain the quality of community life” [37] (pp. 33–34). In this relation, youth empowerment on the collective level can be carried out through educational, interpersonal, or civic engagement opportunities based on the activities provided by those working with the youth [46], where these activities also engage and mobilize the youth towards social action [42]. Both the individual and collective empowerment as described above may indicate the traditional top-down approach to empowerment, rather than the circular reciprocal empowerment. The top-down empowerment is linear power -over exchanges [47] whereas the ones with power empowering the ones without; while reciprocal empowerment is circular and it is not only empowering others but also oneself: a mutual empowerment rather than one-sided [47][48].

Empowerment can, amongst other things, be gained through an ecosocial work perspective which strives to empower people and enhance their agency over their lives, through a more ecocentric approach; it also aims to promote and enhance the wellbeing of people and the planet. When discussing empowerment, notions of power and the implications of the powerful–powerless dichotomy are unavoidable. Power is a central concept in Foucault’s works, such as The Archaeology of Knowledge (1972), Discipline and Punish (1995), and The Order of Things (2005). In these works, Foucault opines that institutions can be understood in terms of techniques of power that are a form of “power/knowledge” that observes, monitors, shapes and controls people’s behavior [49][50][51]. Power is comprised of the rationalities by which one governs the conduct of others. It is not only repressive, negative, or destructive, but also positive and constructive in the sense of being constitutive in the shaping of people’s lives and ideas [49]; however, power is not exercised solely by those who hold institutional power; it is also located in a more diffuse assembly of groupings, including those who are oppressed, as through resistance they can possess “power against” [50][52].

As in the work of Foucault, the notion of power in this entry is inextricably related to knowledge, since those in power produce the dominant knowledge within the discourse studied. Knowledge governs the discursive practices that determine what is “true” or “false” [53]. Within the Foucauldian perspective, alternative forms of knowledge are recognized, allowing consideration that power is not possessed and “one way”, but rather is exercised and circuitous with multiple sources [54]. Foucault developed the “power/knowledge” unity, discussing how knowledge is an exercise of power and power is a function of knowledge [55]. Power produces knowledge, and the operation of power is used through the construction of knowledge [56]. Power/knowledge is “the deployment of force and the establishment of truth” [50] (p. 184). This means that knowledge relies on an acceptance of truth established, and power/knowledge operates everywhere where there is any kind of power relation, in all interactions, and in the institutions and systems that people create.

Within the modernist social work approach towards empowerment, there is a power relationship between professionals/practitioners and clients. The professionals/practitioners have certain power over the clients, which is embedded within their professional roles and positions [57]. This power, if not exercised carefully, could instead unintentionally disempower the clients and service users, such as the youth population. As power is not given/possessed but rather exercised [54][55], “giving” the power to the youth to create a new narrative for their lives, but without giving them proper support, tools, knowledge and resources in how to exercise the power, will be meaningless. On top of that, those working with the youth should recognize that the distribution of power exercise among the youth could carry disempowering effects, if it is for example based on which youth can/most likely to participate (for example, most youth who participated in the activities provided by the youth centers in this entry, were mostly boys, with some efforts by the centers in recruiting more girls by offering e.g.“movie night for girls”).

Following the work of Foucault, which is rooted in post-modernist, post-structuralist, and deconstructionist philosophy, postmodern social work theorists have identified that the concept of empowerment in social work is centered excessively around sovereignty, state control, and institutional power, instead of realizing that power is everywhere and relational [52]. Postmodern analysis of empowerment in social work encourages social work practitioners to consider their own interpretations [58], and to not only consult the service users but also offer them the interpretive framework to determine interventions [59]; it also inspires deconstruction of the main modernist concepts in social work, and simultaneously provides new ways for social workers to conceptualize power and empowerment in constructing more relevant approaches to contemporary social work [52].

While adult empowerment is dominated by civic participation, youth empowerment is often concerned more with preventative intervention; that is, the prevention of problem behaviors and negative outcomes [5], and at the same time, enhancement of resilience among the youth through educational settings [42]. This preventative work is based on the knowledge of the practitioners who work with young people, which can mean that these practitioners have the power of imposing surveillance upon the youth (see Ref. [48]). The knowledge of these practitioners is a result of their interaction with their colleagues and other actors working with youth, forming a community of practice that focuses on the management of knowledge and how it is used [60]. The preventative intervention approach in youth empowerment can be translated as empowerment on an individual basis, aiming to prevent and/or reduce undesired behaviors and at the same time to develop and strengthen the individual; however, this individual strength perspective carries a risk that the empowerment might become too individualized. While individual empowerment is important, in addressing structural issues such as SD and the SDGs there is a need to combine it with collective empowerment based on collective identity. In relation to SD and the SDGs, as well as the Fridays for Future, youth are seen and act collectively as a community and identity: a homogenous group with joint interests consisting of heterogeneous individuals and identities. According to Foucault, individual identities are recognized, socially constructed and regulated within certain discourses [61]. Consequently, collective identity is when two or more individuals act as social objects based on reciprocal attribution and shared affirmation. When there is a collective identity, it can be assumed that there is a community and vice versa. Community refers to local community, residential area, neighborhood, local society, interest groups, togetherness, and more-which includes both social and geographical aspects [17]. In this entry, the youth is seen as a community with a collective identity based on the shared social aspects, such as being left behind in relation to climate issue discourse, which affect their need for a liveable planet.

Youth engagement through youth empowerment is said to increase youth’s developmental assets and understanding of complex issues such as environmental protection [19]. It is important to engage youth in working towards all the SDGs at all levels [62], especially as many of the SDGs are directed towards them. Through youth empowerment, combined with the acknowledgment that young people are future agents of change and that their developmental processes are pivotal in building a prosperous and sustainable future, youth are crucial in assisting the realizations of the SDGs. Good health and wellbeing are both requirements for and outcomes of the SDGs, and can also promote sustainable work-life capacities for all; however, good health and wellbeing are important and necessary not only for humans, but also for non-humans and for the planet people live on. It is thus important to promote and advocate for human and non-human wellbeing, as well as human work-life capacities, through ecosocial work and an SD framework. Even though SD and the SDGs were created in anthropocentric terms, there are possibilities to promote the health and wellbeing of non-human sentient animals and non-sentient parts of nature such as plants, oceans, and the ecosystem directly within the SD framework through some of the goals [9].

References

- Matthies, A.-L. The Conceptualization of Ecosocial Transition. In The Ecosocial Transition of Societies: The Contribution of Social Work and Social Policy; Matthies, A.-L., Närhi, K., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 17–35.

- Hwang, S.; Kim, J. UN and SDGs: A Handbook for Youth. Available online: https://www.unescap.org/resources/un-and-sdgs-handbook-youth (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Rocha, E.M. A Ladder of Empowerment. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1997, 17, 31–44.

- Wiley, A.; Rappaport, J. Empowerment, Wellness and the Politics of Development. In The Promotion of Wellness in Children and Adolescents; Cicchetti, D., Rappaport, J., Sandler, I., Weissberg, R.P., Eds.; Child Welfare League of America Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; pp. 59–99. ISBN 0878687912.

- Rivera, A.C.; Seidman, E. Empowerment Theory and Youth. In Encyclopedia of Applied Developmental Science; Fisher, C.B., Lerner, R.M., Eds.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 401–403. ISBN 0-7619-2820-0.

- SDSN-Youth. Youth Solutions Report; SDSN-Youth: New York, NY, USA, 2020.

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future; World Commission on Environment and Development: New York, NY, USA, 1987.

- Keitsch, M. Structuring Ethical Interpretations of the Sustainable Development Goals—Concepts, Implications and Progress. Sustainability 2018, 10, 829.

- Torpman, O.; Röcklinsberg, H. Reinterpreting the SDGs: Taking Animals into Direct Consideration. Sustainability 2021, 13, 843.

- Ife, J. Radically Transforming Human Rights for Social Work Practice. Available online: https://www.aasw.asn.au/document/item/9560 (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Sustainable Development: History. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Elkington, J. Enter the Triple Bottom Line. In The Triple Bottom Line: Does It All Add Up; Henriques, A., Richardson, J., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–16. ISBN 978-1-84407-016-9.

- Svenska Unescorådet. ESD for 2030. Available online: https://unesco.se/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/ESD-for-2030.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2022).

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development: A Roadmap; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2020; ISBN 9789231003943.

- Bexell, S.M.; Sparks, J.L.D.; Tejada, J.; Rechkemmer, A. An Analysis of Inclusion Gaps in Sustainable Development Themes: Findings from A Review of Recent Social Work Literature. Int. Soc. Work 2019, 62, 864–876.

- Barthel, S.; Colding, J.; Hiswåls, A.-S.; Thalén, P.; Turunen, P. Urban Green Commons for Socially Sustainable Cities and Communities. Nord. Soc. Work Res. 2021, 1–13.

- Sjöberg, S.; Turunen, P. Samhällsförändringar som Utmanar. In Samhällsarbete: Aktörer, Arenor och Perspektiv; Sjöberg, S., Turunen, P., Eds.; Studentlitteratur AB: Lund, Sweden, 2018; pp. 45–65.

- Finn, J.L.; Checkoway, B. Young People as Competent Community Builders: A Challenge to Social Work. Soc. Work 1998, 43, 335–345.

- Schusler, T.; Krings, A.; Hernández, M. Integrating Youth Participation and Ecosocial Work: New Possibilities to Advance Environmental and Social Justice. J. Community Pract. 2019, 27, 460–475.

- Krings, A.; Victor, B.G.; Mathias, J.; Perron, B.E. Environmental Social Work in the Disciplinary Literature, 1991–2015. Int. Soc. Work 2020, 63, 275–290.

- Powers, M.; Rinkel, M.; Kumar, P. Co-Creating a “Sustainable New Normal” for Social Work and Beyond: Embracing an Ecosocial Worldview. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10941.

- Truell, R. News from Our Societies–IFSW: Social Work and Co-building A New Eco-social World. Int. Soc. Work 2021, 64, 625–627.

- Närhi, K. The Eco-Social Approach in Social Work and the Challenges to the Expertise of Social Work; University of Jyväskylän: Jyväskylä, Finland, 2004.

- Närhi, K.; Matthies, A.-L. The Ecosocial Approach in Social Work as A Framework for Structural Social Work. Int. Soc. Work 2018, 61, 490–502.

- Peeters, J. The place of social work in sustainable development: Towards ecosocial practice. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2012, 21, 287–298.

- Boetto, H. A Transformative Eco-Social Model: Challenging Modernist Assumptions in Social Work. Br. J. Soc. Work 2017, 47, 48–67.

- Turunen, P.; Matthies, A.-L.; Närhi, K.; Boeck, T.; Albers, S. Practical Models and Theoretical Findings in Combating Social Exclusion. In The Eco-Social Approach in Social Work; Matthies, A.-L., Närhi, K., Ward, D., Eds.; SoPhi, University of Jyväskylä: Jyväskylä, Finland, 2001; pp. 108–123.

- Bell, K. A Philosophy of Social Work beyond the Anthropocene. In Post-Anthropocentric Social Work Critical Posthuman and New Materialist Perspectives; Bozalek, V., Pease, B., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 58–67. ISBN 978-0-429-32998-2.

- Ramsay, S.; Boddy, J. Environmental Social Work: A Concept Analysis. Br. J. Soc. Work 2017, 47, 68–86.

- Bozalek, V.; Pease, B. Towards Post-Anthropocentric Social Work. In Post-Anthropocentric Social Work Critical Posthuman and New Materialist Perspectives; Bozalek, V., Pease, B., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–15.

- Webb, S. What Comes after the Subject? Towards a Critical Posthumanist Social Work. In Post-Anthropocentric Social Work Critical Posthuman and New Materialist Perspectives; Bozalek, V., Pease, B., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 19–31. ISBN 978-0-429-32998-2.

- Susen, S. Reflections on the (Post-) Human Condition: Towards New Forms of Engagement with the World. Soc. Epistemol. 2022, 36, 63–94.

- Rambaree, K.; Faxelid, E. Considering Abductive Thematic Network Analysis with ATLAS.ti 6.2. In Advancing Research Methods with New Media Technologies; Sappleton, N., Ed.; IGI Global: Hersley, PA, USA, 2003; pp. 170–186.

- IFSW Global Definition of Social Work. Available online: www.ifsw.org/what-is-social-work/global-definition-of-social-work/ (accessed on 28 March 2021).

- Adams, R. Social Work and Empowerment; Macmillan Press, Ltd.: London, UK, 1996; ISBN 978-0-333-65809-3.

- Freire, P. The Pedagogy of the Oppressed; Seabury Press: New York, NY, USA, 1970.

- Jennings, L.B.; Parra-Medina, D.B.; Hilfinger-Messias, D.K.; McLoughlin, K. Toward a Critical Social Theory of Youth Empowerment. J. Community Pract. 2008, 14, 31–55.

- Rappaport, J. Terms of Empowerment/Exemplars of Prevention: Toward a Theory for Community Psychology. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1987, 15, 121–148.

- Goodman, R.M.; Speers, M.A.; McLeroy, K.; Fawcett, S.; Kegler, M.; Parker, E.; Smith, S.R.; Sterling, T.D.; Wallerstein, N. Identifying and Defining the Dimensions of Community Capacity to Provide a Basis for Measurement. Health Educ. Behav. 1998, 25, 258–278.

- Zimmerman, M.A.; Rappaport, J. Citizen Participation, Perceived Control, and Psychological Empowerment. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1988, 16, 725–750.

- Minkler, M.; Wallerstein, N. Improving Health through Community Organization and Community Building: Perspectives from Health Education and Social Work. In Community Organizing and Community Building for Health and Welfare; Minkler, M., Ed.; Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 37–58. ISBN 978-0-8135-5314-6.

- Maton, K.I. Empowering Community Settings: Agents of Individual Development, Community Betterment, and Positive Social Change. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 41, 4–21.

- Sjöberg, S.; Rambaree, K.; Jojo, B. Collective Empowerment: A Comparative Study of Community Work in Mumbai and Stockholm. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2015, 24, 364–375.

- Zimmerman, M.A. Psychological Empowerment: Issues and Illustrations. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1995, 23, 581–599.

- Zimmerman, M.A. Empowerment Theory: Psychological, Organizational and Community Levels of Analysis. In Handbook of Community Psychology; Rappaport, J., Seidman, E., Eds.; Plenum Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 46–63. ISBN 978-1-4615-4193-6.

- Nicholas, C.; Eastman-Mueller, H.; Barbich, N. Empowering Change Agents: Youth Organizing Groups as Sites for Sociopolitical Development. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2019, 63, 46–60.

- Kim, D.J. Reciprocal Empowerment for Civil Society Peacebuilding: Sharing Lessons between the Korean and Northern Ireland Peace Processes Lessons between the Korean and Northern Ireland Peace Processes. Globalizations 2022, 19, 238–252.

- Darlington, P.S.E.; Mulvaney, B.M. Women, Power, and Ethnicity: Working toward Reciprocal Empowerment; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2003; ISBN 9781315865218.

- Foucault, M. The Archaeology of Knowledge and the Discourse on Language; Pantheon Books: New York, NY, USA, 1972; ISBN 0-394-71106-8.

- Foucault, M. Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison, 2nd ed.; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1995.

- Foucault, M. The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences; Routledge: London, UK, 2005; ISBN 9781444334067.

- Pease, B. Rethinking Empowerment: Emancipatory Practice. Br. J. Soc. Work 2002, 32, 135–147.

- Foucault, M.; Gros, F.; Ewald, F.; Fontana, A. The Government of Self and Others: Lectures at the Collège de France 1982–1983; Gros, F., Ewald, F., Fontana, A., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2010; pp. 285–297. ISBN 978-0-230-27473-0.

- Khan, T.H.; MacEachen, E. Foucauldian Discourse Analysis: Moving Beyond a Social Constructionist Analytic. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2021, 20, 1–9.

- Foucault, M. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972–1977; Gordon, C., Ed.; Pantheon Books: New York, NY, USA, 1980; ISBN 0394513576.

- Foucault, M. The History of Sexuality, Volume 1: An Introduction; Pantheon Books: New York, NY, USA, 1978; ISBN 0394417755.

- Adams, R. Empowerment, Participation and Social Work, 4th ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-1-137-05053-3.

- Healy, B.; Fook, J. Reinventing Social Work. In Advances in Social Work and Welfare Education; Ife, J., Leitman, S., Murphy, P., Eds.; AASWWE: Perth, WA, Australia, 1994; pp. 42–55.

- Parker, S.; Fook, J.; Pease, B. Empowerment: The Modern Social Work Concept Par Excellence. In Transforming Social Work Practice: Postmodern Critical Perspectives; Pease, B., Fook, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 150–160. ISBN 9780203164969.

- Wenger, E. Knowledge Management as A Doughnut: Shaping Your Knowledge Strategy through Communities of Practice. Ivey Bus. J. 2004, 68, 1–8.

- Baxter, J. Positioning Language and Identity. In The Routledge Handbook of Language and Identity; Preece, S., Ed.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 34–49. ISBN 9780367353896.

- Kleinert, S.; Horton, R. Adolescent Health and Wellbeing: A Key to A Sustainable Future. Lancet 2016, 387, 2355–2356.

More

Information

Subjects:

Social Work

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

4.1K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

21 Apr 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No