Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Konark Mukherjee | -- | 2426 | 2022-04-19 18:28:38 | | | |

| 2 | Beatrix Zheng | + 109 word(s) | 2535 | 2022-04-20 06:19:25 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Mukherjee, K.; , .; Srivastava, S. The Molecular Function of Calcium/Calmodulin-Dependent Serine Protein Kinase. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21960 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Mukherjee K, , Srivastava S. The Molecular Function of Calcium/Calmodulin-Dependent Serine Protein Kinase. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21960. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Mukherjee, Konark, , Sarika Srivastava. "The Molecular Function of Calcium/Calmodulin-Dependent Serine Protein Kinase" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21960 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Mukherjee, K., , ., & Srivastava, S. (2022, April 19). The Molecular Function of Calcium/Calmodulin-Dependent Serine Protein Kinase. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21960

Mukherjee, Konark, et al. "The Molecular Function of Calcium/Calmodulin-Dependent Serine Protein Kinase." Encyclopedia. Web. 19 April, 2022.

Copy Citation

MICPCH (microcephaly and pontocerebellar hypoplasia) is a monogenic condition that results from variants of an X-linked gene, CASK (calcium/calmodulin-dependent serine protein kinase). CASK variants are associated with a wide range of clinical presentations, from lethality and epileptic encephalopathies to intellectual disabilities, microcephaly, and autistic traits. The researches point to a highly complex relationship between the potential molecular function/s of CASK and the phenotypes observed in model organisms and humans.

CASK

MICPCH

pontocerebellar hypoplasia

pathogenesis

1. The Molecular Function of CASK

CASK (calcium/calmodulin-dependent serine protein kinase) can interact with a large number of proteins, leading to the idea that CASK is a scaffolding molecule [1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13]. Mammalian CASK was identified due to its ability to bind neurexin [14]. CASK can also interact with other membrane proteins such as syndecan and syncam [13][15][16]. CASK forms an evolutionarily conserved tripartite complex with two other molecules—Mint1 (lin-3) and veli (lin-7) [2][17]. Although at first glance, these data support the notion that CASK might participate in the let-23 pathway, within neurons, this conserved complex is thought to be presynaptic. The interaction of Mint-1 with CASK is competitive with other molecules such as Caskin, Tiam, and liprin-α [18][19][20]. The interaction of CASK with liprin-α is specific to vertebrates. Liprin-α can also additionally interact with the CASK-neurexin complex, an interaction which is modifiable by phosphorylation of neurexins [18][20]. Due to specific substitutions in the primary structure, both the CaM kinase domain and GuK domain of CASK were initially assumed to be enzymatically inactive [21][22]. Careful analysis, however, indicated that the CASK CaM kinase domain was an unusual kinase inhibited by divalent ions, including the kinase co-factor magnesium [23][24]. Due to its slow activity, CASK can only phosphorylate its interacting partners, such as neurexin. Such phosphorylation events are likely to alter protein–protein interactions, as has been demonstrated for the CASK-neurexin-liprin-α interaction [18]. Although the CASK–neurexin interaction is typically described to be PDZ domain-mediated, biochemical experiments have indicated that the entire C-terminus region may be involved in this interaction [14]. The structural basis for this has been also described, demonstrating that the PDZ, SH3, and GuK domain form an integrated supradomain, which is required for the interaction between CASK and neurexin [25]. By analyzing CASK missense variants associated with MICPCH, the researchers uncovered that disruption of this integrated C-terminus-mediated interaction, rather than the CASK-Tbr1 interaction, is more likely to be critical for inducing MICPCH [26]. This finding has been reproduced by another group [27]. However, variants throughout CASK are associated with developmental delay and MICPCH, demonstrating the difficulty of genotype–phenotype correlations at a protein structure level [26][28][29][30][31]. The researchers have shown that many of the missense variants may actually lead to destabilization of the CASK structure and thus affect its overall function.

Much of the available literature on CASK points to a putative synaptic function (Figure 1). As mentioned above, CASK can interact with the presynaptic protein neurexin and link it with active zone organizer liprin-α in a regulated manner. Further, liprin-α may regulate CASK turnover within the presynaptic active zone [32]. These function/s of CASK could be crucial for neurotransmission. Human-induced neurons with CASK variants showed a reduction in presynaptic protein levels, but this data is difficult to interpret because the research team found the opposite effect when knocking down CASK in wild-type neurons. Further complicating the effort to look at effects on gene expression was the fact that the proportion of the neuron type (excitatory vs. inhibitory) that developed was altered in induced cells with CASK variants [33]. These data exemplify the difficulties of interpreting data acquired from cultured neurons in general and induced neurons specifically. On the postsynaptic side, CASK may interact with syndecan or CamKII via its interaction with Tbr1, and it can also alter the function of NMDA receptors by upregulating the NR2b subunit [15][34][35]. CASK thus may function in spinogenesis [36], synaptic plasticity, and neurotransmission. Indeed Mori et al. demonstrated that in the absence of CASK in post-synaptic neurons, there is a reduction in action potential-independent inhibitory current frequency and an increase in action potential-independent excitatory current frequency [37]. These data are consistent with findings in neurons from constitutive Cask knockout mice [38]. In the Cask+/− mouse, the researchers have demonstrated a decrease in release sites in the retinogeniculate connections [39]. The researchers have also uncovered a decrease in the level of all active zone proteins and a concomitant increase in many glutamatergic post-synaptic proteins, further strengthening the notion of a synaptic role for CASK [40]. Additionally, CASK can interact with CNTNAP2 to stabilize dendritic arbors, specifically in cortical GABAergic inhibitory neurons [41].

Figure 1. Working models of CASK molecular function. Model 1 shows CASK forming a complex with CASK-interacting nucleosome assembly protein (CINAP) and T-Box brain transcription factor 1 (Tbr1) to upregulate transcription of reelin and NR2b. Model 2 depicts CASK interacting with presynaptic adhesion molecule neurexin to nucleate a complex with Mint-1, veli, and the active zone (AZ) organizer liprin-α. SV = synaptic vesicle cluster. Model 3 depicts CASK interacting with transmembrane proteoglycan called syndecan on the postsynaptic side. Interaction of CASK with protein 4.1 (P4.1) via its hook motif allows nucleation of actin and spine maintenance.

Could all these putative functions of CASK underlie the MICPCH phenotype? The cerebellar hypoplasia in MICPCH most predominantly affects glutamatergic granule cells rather than GABAergic Purkinje cells [42][43]. Furthermore, the CNTNAP2 knockout mice do not display lethality or cerebellar hypoplasia [44]. Granule cells degenerate before formation of the inner granule layer and parallel fiber connections to Purkinje cells. In fact almost all synapses on Purkinje cells in MICPCH were found to be perisomatic and likely belonging to climbing fibers [43]. Further, abolishing neuronal activity or synaptic transmission in granule cells does not produce cerebellar degeneration ([45][46] and personal communication with Michael Fox). Finally, the researchers' experiment with acute deletion of CASK did not produce locomotor incoordination, indicating that the synaptic function(s) of CASK may not directly translate into symptomatology [43]. Thus although CASK may participate in many synaptic functions which could contribute to some phenotypes seen with CASK variants, there are likely to be additional cellular functions of CASK that are responsible for the phenotypes seen in MICPCH.

A fraction of CASK expressed by a cell is cytosolic and exists as part of larger protein complexes [42]. To fully describe the protein complexes associated with CASK, the researchers have performed extensive immunoprecipitation and pulldown experiments. First, the researchers performed such experiments in the fly model and were able to confirm many of the previously known CASK interactions, including with Mint, veli, neurexin, and CaMKII [47]. Surprisingly, the researchers found that CASK likely interacts with different proteins in different neurons, allowing for functional diversification of CASK. A common set of proteins that immunoprecipitated with CASK were mitochondrial [47]. Strikingly, none of the mitochondrial genome-encoded proteins were precipitated with CASK, indicating that CASK was not interacting with mature complexes present in mitochondria, but rather with mitochondrial proteins outside of the mature mitochondria. The researchers also performed pulldown experiments from the rat brain and found that CASK was part of four distinct complexes: (1) synaptic, (2) ribosomal/protein chaperone, (3) cytoskeletal, and (4) mitochondrial [40]. CASK protein–protein interactions may thus be conserved in different animal models.

The researchers next tested whether these interactions have any physiological relevance. They examined transcriptomic changes in the Cask+/− mouse brain by using an RNAseq approach; only ~100 transcripts exhibited significant changes, of which many were extracellular matrix (ECM) molecules. Changes in the ECM are noted in other neurodegenerative conditions [48] and may reflect ECM turnover. And although CASK purportedly interacts with Tbr1, strikingly, they did not observe changes in the transcript levels of the proteins proposed to be regulated by the CASK-Tbr1 complex (reelin and Nr2b). Others have also observed that Tbr1 may not regulate reelin expression in the cerebellum [49].

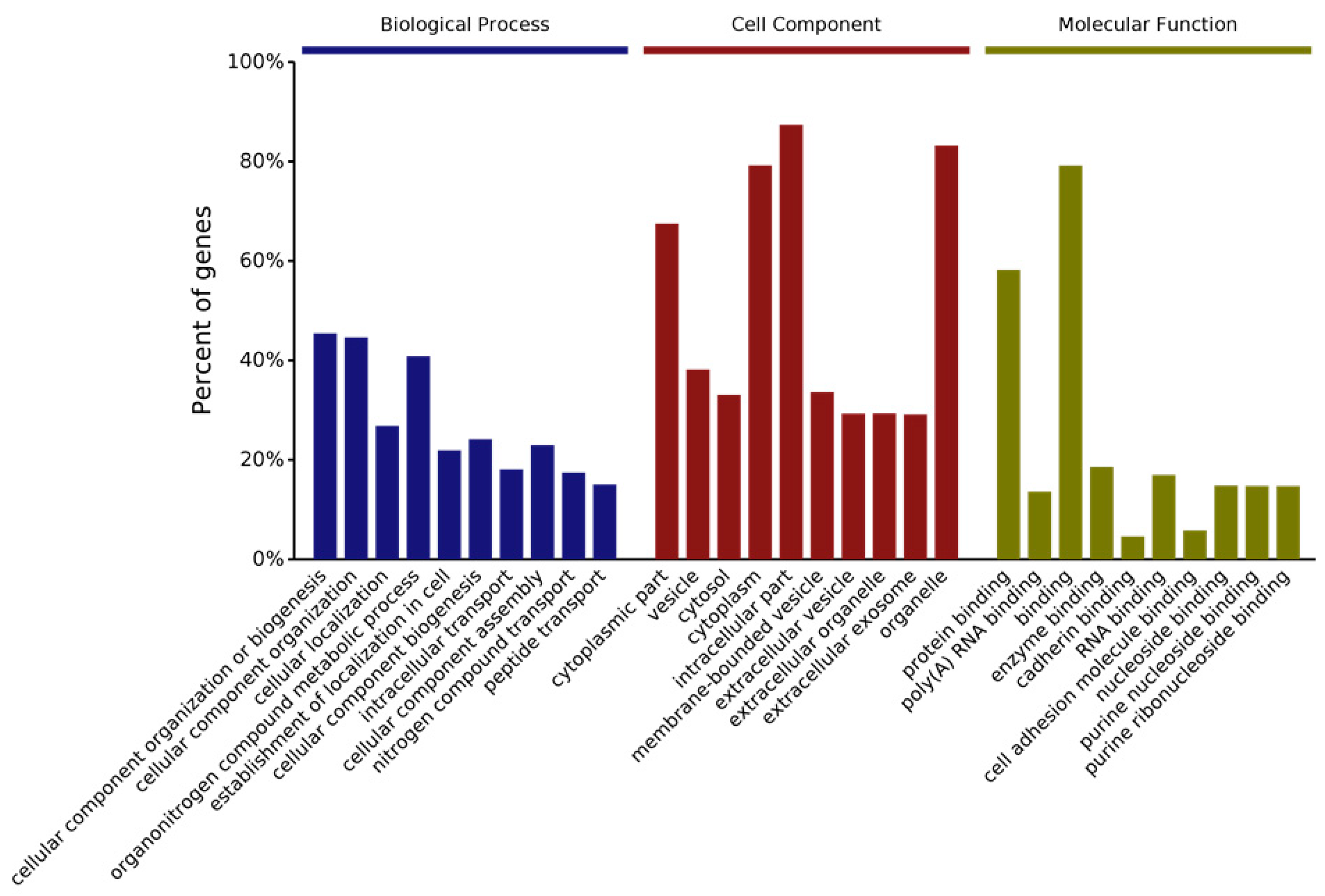

The researchers have also examined changes in protein levels by using quantitative proteomics. More than 500 proteins are differentially expressed in Cask+/− mice. Interestingly, these differentially expressed proteins fall into the same categories occupied by the proteins with which CASK forms complexes [40]. Ninety-nine of the proteins belong to the mitochondrial group, affirming the researchers' earlier findings of a link between CASK and the mitochondrion and suggesting that CASK regulates mitochondrial function in addition to synaptic function [40]. Gene ontology or GO analysis, which broadly classifies proteins based on their properties (molecular function, cellular component, or biological process), was used to look at what types of proteins change with CASK loss. In the “molecular functions” category, most affected proteins are related to protein binding (including enzymes) and nucleic acid binding. CASK loss affects proteins associated with a wide range of cellular components, both membranous and cytoplasmic, consistent with CASK’s distribution. And finally, according to the GO classification, the biological processes most affected with CASK loss range from metabolism to cellular organization and intracellular transport of proteins (Figure 2). Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genetics and Genomics (KEGG) pathway analysis of protein changes with CASK loss indicates that the highest significance is associated with neurodegenerative conditions such as Parkinson’s disease and the metabolic pathway of oxidative phosphorylation (Figure 3). These bioinformatics findings are corroborated by the researchers' experimental work, in which the researchers indeed observed a loss of the substantia nigra pars compacta in the brain lacking CASK and also have biochemical evidence that mitochondrial respiration and glucose oxidation are reduced in the brains of Cask+/− mice. In addition to metabolism, other fundamental pathways including protein translation and intra- and inter-cellular signaling are also affected by CASK loss (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Gene ontology (GO) analysis of protein changes from whole brain of Cask+/− mice compared to wild-type littermates. iTRAQ quantitative proteomic analysis was performed to evaluate global changes at protein level. Bar graphs shows top 10 GO annotation categories including biological process (blue), cell component (red), and molecular function (green).

Figure 3. KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) pathway analysis of protein changes from whole brain of Cask+/− mice compared to wild-type littermates. iTRAQ quantitative proteomic analysis was performed to evaluate global changes at protein level. KEGG pathway analysis was performed on the molecules. Significantly affected pathways are shown in metabolism (upper panel) and human disease pathway (lower panel) are shown. The full figure can be found in the supplemental file.

The first CASK ortholog (C. elegans) to be discovered (lin-2) in 1978 was found to be a part of an evolutionarily conserved tripartite complex (with lin-7 and lin-10) [2][17], which may be localized to the Golgi complex [17][50][51]. In flies, CASK has been isolated with mitochondrial membranes [47]. Within the soma of a mammalian neuron, CASK can be found in a distinct punctate (organelle) distribution [16]. It has been suggested that CASK is localized to the endoplasmic reticulum, whereas its interactor Mint-1 (lin-10) has been localized to the Golgi complex and veli (lin-7) has been found on mitochondria [6][52][53]. Multiple studies have identified CASK as a probable constituent of mitochondria-associated membrane [54][55]. It is thus conceivable that CASK is involved in a more general protein folding and trafficking process, thereby affecting a wide range of functions including synaptic neurotransmission and metabolism [40]. This notion is in line with the ubiquitous expression of CASK in nearly all tissue types [14][56].

Several important questions remain to be answered about the molecular, cellular, and biological functions of CASK. For instance, does CASK have different functions in different cellular types? Experiments from Drosophila suggest that CASK may interact with different sets of proteins in different neuronal populations. The studies described here in-depth have all been done in brain tissue; CASK interactions may be even more diverse in different organs [47]. The cellular function of CASK is thus likely to be context-specific in different cell types, and the cumulative loss of these CASK functions contribute to the overall phenotype of MICPCH. The role of CASK throughout the body has been postulated to be impressively broad, including possible contributions to insulin secretion and signaling, cell proliferation, kidney development, heart conductivity, epithelial cell polarization, cancer biology, and sperm development, just to name a few [11][57][58][59][60][61][62], suggesting that CASK dysfunction leads to systemic effects that are hard to disentangle from each other.

2. Reconciling CASK’s Molecular Function with Its Loss-of-Function Pathology

It is often not easy to correlate the pathology of a genetic disorder with the specific molecular function/s of the gene. For example, mitochondrial encephalopathies can have phenotypes that overlap substantially with those caused by variants in proteins that glycosylate macromolecules [63]. The researchers are, however, able to provide a rough outline of the connection between genotype and phenotype from the researchers' studies of CASK. Loss of CASK produces PCH [64]. In most instances, PCH has been classified as a degenerative disorder with a prenatal onset [65]. At present, more than 11 subtypes of PCH have been described based on clinical and radiographic features. Many of the genes that have been tied to PCH are involved in tRNA function [65]. Other genes associated with PCH include the mitochondrial arginylyl tRNA synthetase (RARS2) and the exosome genes Exosc 3 and 8 [65]. Careful consideration of these associations strongly suggests that dysfunction in protein translation, mitochondrial metabolism, and exosomal dysfunction positively correlate with the occurrence of PCH. What remains to be uncovered is why defects in these particular functions specifically affect the hindbrain.

PCH with CASK loss also begins prenatally in the third trimester. As seen with PCH, proteomic changes in the brains of mice with heterozygous deletion of Cask feature mitochondrial and exosomal proteins, as well as proteins involved in translation (Figure 2 and Figure 3). It is possible that loss of CASK destabilizes these vital cellular functions and thus produces PCH. PCH caused by CASK variants has traditionally been considered non-degenerative. Some authors have gone further and concluded that CASK-linked PCH arises via a unique mechanism because there are no observed deficits in supratentorial structures (it is important to note, however, that many of those conclusions were drawn from the investigation of female heterozygous cases) [66][67]. Unlike other PCH-associated genes, CASK is an X-linked gene subject to random inactivation, meaning that in females with a heterozygous CASK variant, at least 50% of their brain cells have a normal complement of CASK (mosaic status); in this setting, the disorder produced by CASK variant is non-progressive in nature. The researchers have demonstrated, however, that total deletion of Cask produces progressive cerebellar atrophy and that supratentorial atrophy is, in fact, present in CASK-linked PCH in males [68][69]. Much evidence thus strongly suggests that CASK-linked PCH is mechanistically similar to other forms of PCH. In line with this notion, there is substantial overlap in the clinical and neuroradiological presentations of CASK and TSEN54-related disorders [70]. Moreover, CASK variants have been associated with PCH 2, 3, and 4 [66][71]. CASK variants may, in fact, be one of the most common causes of PCH [70]. Clearly, more human case studies are necessary to gather definitive evidence of neurodegeneration in these disorders.

A confounding property of CASK’s pathogenesis is that neuronal loss due to CASK loss-of-function occurs in a non-cell-autonomous fashion. How the dysfunction produced within cells by loss of CASK gives rise to non-cell-autonomous neuronal loss remains unclear. It is not known whether PCH associated with other genes also occurs due to similar non-cell-autonomous effects. It is pertinent to mention that non-cell-autonomous toxicity has been proposed to underlie many neurodegenerative conditions [72]. Further research on CASK is likely to shed light on the mechanism of non-cell-autonomous toxicity and the hindbrain’s vulnerability to CASK dysfunction. In addition to PCH, CASK variants also cause microcephaly. Microcephaly is a co-morbidity of several other PCH types and not unique to CASK variants [73].

References

- Biederer, T.; Südhof, T.C. CASK and Protein 4.1 Support F-actin Nucleation on Neurexins. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 47869–47876.

- Butz, S.; Okamoto, M.; Südhof, T.C. A Tripartite Protein Complex with the Potential to Couple Synaptic Vesicle Exocytosis to Cell Adhesion in Brain. Cell 1998, 94, 773–782.

- Tabuchi, K.; Biederer, T.; Butz, S.; Südhof, T.C. CASK Participates in Alternative Tripartite Complexes in which Mint 1 Competes for Binding with Caskin 1, a Novel CASK-Binding Protein. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 4264–4273.

- Marble, D.D.; Hegle, A.P.; Snyder, E.D., 2nd; Dimitratos, S.; Bryant, P.J.; Wilson, G.F. Camguk/CASK enhances Ether-a-go-go potassium current by a phosphorylation-dependent mechanism. J. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 4898–4907.

- Kuo, T.-Y.; Hong, C.-J.; Chien, H.-L.; Hsueh, Y.-P. X-linked mental retardation gene CASK interacts with Bcl11A/CTIP1 and regulates axon branching and outgrowth. J. Neurosci. Res. 2010, 88, 2364–2373.

- Jeyifous, O.; Waites, C.L.; Specht, C.G.; Fujisawa, S.; Schubert, M.; Lin, E.I.; Marshall, J.; Aoki, C.; de Silva, T.; Montgomery, J.M.; et al. SAP97 and CASK mediate sorting of NMDA receptors through a previously unknown secretory pathway. Nat. Neurosci. 2009, 12, 1011–1019.

- Huang, T.-N.; Chang, H.-P.; Hsueh, Y.-P. CASK phosphorylation by PKA regulates the protein-protein interactions of CASK and expression of the NMDAR2b gene. J. Neurochem. 2010, 112, 1562–1573.

- Hodge, J.; Mullasseril, P.; Griffith, L. Activity-Dependent Gating of CaMKII Autonomous Activity by Drosophila CASK. Neuron 2006, 51, 327–337.

- Chung, W.C.; Huang, T.N.; Hsueh, Y.P. Targeted deletion of CASK-interacting nucleosome assembly protein causes higher locomotor and exploratory activities. Neurosignals 2011, 19, 128–141.

- Aravindan, R.G.; Fomin, V.P.; Naik, U.P.; Modelski, M.J.; Naik, M.U.; Galileo, D.S.; Duncan, R.L.; Martin-DeLeon, P.A. CASK interacts with PMCA4b and JAM-A on the mouse sperm flagellum to regulate Ca2+ homeostasis and motility. J. Cell. Physiol. 2011, 227, 3138–3150.

- Ahn, S.Y.; Kim, Y.; Kim, S.T.; Swat, W.; Miner, J.H. Scaffolding Proteins DLG1 and CASK Cooperate to Maintain the Nephron Progenitor Population during Kidney Development. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 24, 1127–1138.

- Márquez-Rosado, L.; Singh, D.; Rincón-Arano, H.; Solan, J.L.; Lampe, P.D. CASK (LIN2) interacts with Cx43 in wounded skin and their coexpression affects cell migration. J. Cell Sci. 2012, 125, 695–702.

- Biederer, T.; Sara, Y.; Mozhayeva, M.; Atasoy, D.; Liu, X.; Kavalali, E.T.; Südhof, T.C. SynCAM, a Synaptic Adhesion Molecule That Drives Synapse Assembly. Science 2002, 297, 1525–1531.

- Hata, Y.; Butz, S.; Südhof, T.C. CASK: A novel dlg/PSD95 homolog with an N-terminal calmodulin-dependent protein kinase domain identified by interaction with neurexins. J. Neurosci. 1996, 16, 2488–2494.

- Cohen, A.R.; Wood, D.F.; Marfatia, S.M.; Walther, Z.; Chishti, A.H.; Anderson, J.M. Human CASK/LIN-2 Binds Syndecan-2 and Protein 4.1 and Localizes to the Basolateral Membrane of Epithelial Cells. J. Cell Biol. 1998, 142, 129–138.

- Hsueh, Y.-P.; Yang, F.-C.; Kharazia, V.; Naisbitt, S.; Cohen, A.R.; Weinberg, R.; Sheng, M. Direct Interaction of CASK/LIN-2 and Syndecan Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycan and Their Overlapping Distribution in Neuronal Synapses. J. Cell Biol. 1998, 142, 139–151.

- Kaech, S.M.; Whitfield, C.W.; Kim, S.K. The LIN-2/LIN-7/LIN-10 complex mediates basolateral membrane localization of the C. elegans EGF receptor LET-23 in vulval epithelial cells. Cell 1998, 94, 761–771.

- LaConte, L.E.; Chavan, V.; Liang, C.; Willis, J.; Schonhense, E.M.; Schoch, S.; Mukherjee, K. CASK stabilizes neurexin and links it to liprin-alpha in a neuronal activity-dependent manner. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 3599–3621.

- Stafford, R.L.; Ear, J.; Knight, M.J.; Bowie, J.U. The Molecular Basis of the Caskin1 and Mint1 Interaction with CASK. J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 412, 3–13.

- Wei, Z.; Zheng, S.; Spangler, S.A.; Yu, C.; Hoogenraad, C.C.; Zhang, M. Liprin-mediated large signaling complex organization revealed by the liprin-alpha/CASK and liprin-alpha/liprin-beta complex structures. Mol. Cell 2011, 43, 586–598.

- Boudeau, J.; Miranda-Saavedra, D.; Barton, G.; Alessi, D.R. Emerging roles of pseudokinases. Trends Cell Biol. 2006, 16, 443–452.

- Olsen, O.; Bredt, D.S. Functional Analysis of the Nucleotide Binding Domain of Membrane-associated Guanylate Kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 6873–6878.

- Mukherjee, K.; Sharma, M.; Jahn, R.; Wahl, M.C.; Südhof, T.C. Evolution of CASK into a Mg2+ -Sensitive Kinase. Sci. Signal. 2010, 3, ra33.

- Mukherjee, K.; Sharma, M.; Urlaub, H.; Bourenkov, G.P.; Jahn, R.; Südhof, T.C.; Wahl, M.C. CASK Functions as a Mg2+-Independent Neurexin Kinase. Cell 2008, 133, 328–339.

- Li, Y.; Wei, Z.; Yan, Y.; Wan, Q.; Du, Q.; Zhang, M. Structure of Crumbs tail in complex with the PALS1 PDZ–SH3–GK tandem reveals a highly specific assembly mechanism for the apical Crumbs complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 17444–17449.

- LaConte, L.E.W.; Chavan, V.; Elias, A.F.; Hudson, C.; Schwanke, C.; Styren, K.; Shoof, J.; Kok, F.; Srivastava, S.; Mukherjee, K. Two microcephaly-associated novel missense mutations in CASK specifically disrupt the CASK-neurexin interaction. Hum. Genet. 2018, 137, 231–246.

- Pan, Y.E.; Tibbe, D.; Harms, F.L.; Reissner, C.; Becker, K.; Dingmann, B.; Mirzaa, G.; Kattentidt-Mouravieva, A.A.; Shoukier, M.; Aggarwal, S.; et al. Missense mutations in CASK, coding for the calcium-/calmodulin-dependent serine protein kinase, interfere with neurexin binding and neurexin-induced oligomerization. J. Neurochem. 2021, 157, 1331–1350.

- LaConte, L.E.W.; Chavan, V.; Mukherjee, K. Identification and Glycerol-Induced Correction of Misfolding Mutations in the X-Linked Mental Retardation Gene CASK. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e88276.

- LaConte, L.E.W.; Chavan, V.; DeLuca, S.; Rubin, K.; Malc, J.; Berry, S.; Summers, C.G.; Mukherjee, K. An N-terminal heterozygous missense CASK mutation is associated with microcephaly and bilateral retinal dystrophy plus optic nerve atrophy. Am. J. Med Genet. Part A 2018, 179, 94–103.

- Bozarth, X.; Foss, K.; Mefford, H.C. A de novo in-frame deletion of CASK gene causes early onset infantile spasms and supratentorial cerebral malformation in a female patient. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2018, 176, 2425–2429.

- Studtmann, C.; LaConte, L.E.W.; Mukherjee, K. Comments on: A de novo in-frame deletion of CASK gene causes early onset infantile spasms and supratentorial cerebral malformation in a female patient. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2019, 179, 2514–2516.

- Spangler, S.A.; Schmitz, S.K.; Kevenaar, J.T.; de Graaff, E.; de Wit, H.; Demmers, J.; Toonen, R.F.; Hoogenraad, C.C. Liprin-alpha 2 promotes the presynaptic recruitment and turnover of RIM1/CASK to facilitate synaptic transmission. J. Cell. Biol. 2013, 201, 915–928.

- Becker, M.; Mastropasqua, F.; Reising, J.P.; Maier, S.; Ho, M.-L.; Rabkina, I.; Li, D.; Neufeld, J.; Ballenberger, L.; Myers, L.; et al. Presynaptic dysfunction in CASK-related neurodevelopmental disorders. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 312.

- Hsueh, Y.-P.; Wang, T.-F.; Yang, F.-C.; Sheng, M. Nuclear translocation and transcription regulation by the membrane-associated guanylate kinase CASK/LIN-2. Nature 2000, 404, 298–302.

- Lu, C.S.; Hodge, J.J.; Mehren, J.; Sun, X.X.; Griffith, L.C. Regulation of the Ca2+/CaM-responsive pool of CaMKII by scaffold-dependent autophosphorylation. Neuron 2003, 40, 1185–1197.

- Samuels, B.A.; Hsueh, Y.-P.; Shu, T.; Liang, H.; Tseng, H.-C.; Hong, C.-J.; Su, S.C.; Volker, J.; Neve, R.L.; Yue, D.T.; et al. Cdk5 Promotes Synaptogenesis by Regulating the Subcellular Distribution of the MAGUK Family Member CASK. Neuron 2007, 56, 823–837.

- Mori, T.; Kasem, E.A.; Suzuki-Kouyama, E.; Cao, X.S.; Li, X.; Kurihara, T.; Uemura, T.; Yanagawa, T.; Tabuchi, K. Deficiency of calcium/calmodulin-dependent serine protein kinase disrupts the excitatory-inhibitory balance of synapses by downregulating GluN2B. Mol. Psychiatry 2019, 24, 1079–1092.

- Atasoy, D.; Schoch, S.; Ho, A.; Nadasy, K.A.; Liu, X.; Zhang, W.; Mukherjee, K.; Nosyreva, E.D.; Fernandez-Chacon, R.; Missler, M.; et al. Deletion of CASK in mice is lethal and impairs synaptic function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 2525–2530.

- Liang, C.; Kerr, A.; Qiu, Y.; Cristofoli, F.; Van Esch, H.; Fox, M.A.; Mukherjee, K. Optic Nerve Hypoplasia Is a Pervasive Subcortical Pathology of Visual System in Neonates. Investig. Opthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2017, 58, 5485–5496.

- Patel, P.; Liang, C.; Arora, A.; Vijayan, S.; Ahuja, S.; Wagley, P.; Settlage, R.; LaConte, L.; Goodkin, H.; Lazar, I.; et al. Haploinsufficiency of X-linked intellectual disability gene CASK induces post-transcriptional changes in synaptic and cellular metabolic pathways. Exp. Neurol. 2020, 329, 113319.

- Gao, R.; Piguel, N.; Melendez-Zaidi, A.; Martin-De-Saavedra, M.D.; Yoon, S.; Forrest, M.; Myczek, K.; Zhang, G.; Russell, T.A.; Csernansky, J.G.; et al. CNTNAP2 stabilizes interneuron dendritic arbors through CASK. Mol. Psychiatry 2018, 23, 1832–1850.

- Srivastava, S.; McMillan, R.; Willis, J.; Clark, H.; Chavan, V.; Liang, C.; Zhang, H.; Hulver, M.; Mukherjee, K. X-linked intellectual disability gene CASK regulates postnatal brain growth in a non-cell autonomous manner. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2016, 4, 30.

- Patel, P.A.; Hegert, J.V.; Cristian, I.; Kerr, A.; LaConte, L.E.W.; Fox, M.A.; Srivastava, S.; Mukherjee, K. Complete loss of the X-linked gene CASK causes severe cerebellar degeneration. J. Med Genet. 2022.

- Penagarikano, O.; Abrahams, B.S.; Herman, E.I.; Winden, K.D.; Gdalyahu, A.; Dong, H.; Sonnenblick, L.I.; Gruver, R.; Almajano, J.; Bragin, A.; et al. Absence of CNTNAP2 leads to epilepsy, neuronal migration abnormalities, and core autism-related deficits. Cell 2011, 147, 235–246.

- Somaiya, R.D.; Stebbins, K.; Xie, H.; Garcia, A.D.R.; Fox, M.A. Sonic hedgehog-dependent recruitment of GABAergic interneurons into the developing visual thalamus. bioRxiv 2022.

- Galliano, E.; Gao, Z.; Schonewille, M.; Todorov, B.; Simons, E.; Pop, A.S.; D’Angelo, E.U.; Maagdenberg, A.M.V.D.; Hoebeek, F.E.; De Zeeuw, C.I. Silencing the Majority of Cerebellar Granule Cells Uncovers Their Essential Role in Motor Learning and Consolidation. Cell Rep. 2013, 3, 1239–1251.

- Mukherjee, K.; Slawson, J.B.; Christmann, B.L.; Griffith, L.C. Neuron-specific protein interactions of Drosophila CASK-beta are revealed by mass spectrometry. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2014, 7, 58.

- Bonneh-Barkay, D.; Wiley, C.A. Brain Extracellular Matrix in Neurodegeneration. Brain Pathol. 2009, 19, 573–585.

- Fink, A.J.; Englund, C.; Daza, R.A.M.; Pham, D.; Lau, C.; Nivison, M.; Kowalczyk, T.; Hevner, R.F. Development of the Deep Cerebellar Nuclei: Transcription Factors and Cell Migration from the Rhombic Lip. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 3066–3076.

- Horvitz, H.R.; Sulston, J.E. Isolation and genetic characterization of cell-lineage mutants of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 1980, 96, 435–454.

- Gauthier, K.D.; Rocheleau, C.E. Golgi localization of the LIN-2/7/10 complex points to a role in basolateral secretion of LET-23 EGFR in the Caenorhabditis elegans vulval precursor cells. Development 2021, 148, dev194167.

- Thyrock, A.; Ossendorf, E.; Stehling, M.; Kail, M.; Kurtz, T.; Pohlentz, G.; Waschbüsch, D.; Eggert, S.; Formstecher, E.; Müthing, J.; et al. A New Mint1 Isoform, but Not the Conventional Mint1, Interacts with the Small GTPase Rab6. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e64149.

- Ferrari, I.; Crespi, A.; Fornasari, D.; Pietrini, G. Novel localisation and possible function of LIN7 and IRSp53 in mitochondria of HeLa cells. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2016, 95, 285–293.

- Hung, V.; Lam, S.S.; Udeshi, N.D.; Svinkina, T.; Guzman, G.; Mootha, V.K.; Carr, S.A.; Ting, A.Y. Proteomic mapping of cytosol-facing outer mitochondrial and ER membranes in living human cells by proximity biotinylation. eLife 2017, 6, e24463.

- Poston, C.N.; Krishnan, S.C.; Bazemore-Walker, C.R. In-depth proteomic analysis of mammalian mitochondria-associated membranes (MAM). J. Proteom. 2013, 79, 219–230.

- Stevenson, D.; Laverty, H.G.; Wenwieser, S.; Douglas, M.; Wilson, J.B. Mapping and expression analysis of the human CASK gene. Mamm. Genome 2000, 11, 934–937.

- Caruana, G. Genetic studies define MAGUK proteins as regulators of epithelial cell polarity. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2002, 46, 511–518.

- Qi, J.; Su, Y.; Sun, R.; Zhang, F.; Luo, X.; Yang, Z.; Luo, X. CASK inhibits ECV304 cell growth and interacts with Id1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 328, 517–521.

- Ding, B.; Bao, C.; Jin, L.; Xu, L.; Fan, W.; Lou, W. CASK Silence Overcomes Sorafenib Resistance of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Through Activating Apoptosis and Autophagic Cell Death. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 681683.

- Burkin, H.R.; Zhao, L.; Miller, D.J. CASK is in the mammalian sperm head and is processed during epididymal maturation. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2004, 68, 500–506.

- Mustroph, J.; Sag, C.M.; Bähr, F.; Schmidtmann, A.-L.; Gupta, S.N.; Dietz, A.; Islam, M.T.; Lücht, C.M.; Beuthner, B.E.; Pabel, S.; et al. Loss of CASK Accelerates Heart Failure Development. Circ. Res. 2021, 128, 1139–1155.

- Liu, X.; Sun, P.; Yuan, Q.; Xie, J.; Xiao, T.; Zhang, K.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, L.; Han, X. Specific Deletion of CASK in Pancreatic beta Cells Affects Glucose Homeostasis and Improves Insulin Sensitivity in Obese Mice by Reducing Hyperinsulinemia Running Title: Beta Cell CASK Deletion Reduces Hyperinsulinemia. Diabetes 2022, 71, 104–115.

- Gardeitchik, T.; Wyckmans, J.; Morava, E. Complex Phenotypes in Inborn Errors of Metabolism: Overlapping Presentations in Congenital Disorders of Glycosylation and Mitochondrial Disorders. Pediatric Clin. 2018, 65, 375–388.

- Burglen, L.; Chantot-Bastaraud, S.; Garel, C.; Milh, M.; Touraine, R.; Zanni, G.; Petit, F.; Afenjar, A.; Goizet, C.; Barresi, S.; et al. Spectrum of pontocerebellar hypoplasia in 13 girls and boys with CASK mutations: Confirmation of a recognizable phenotype and first description of a male mosaic patient. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2012, 7, 18.

- Van Dijk, T.; Baas, F.; Barth, P.G. What’s new in pontocerebellar hypoplasia? An update on genes and subtypes. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2018, 13, 92.

- Valayannopoulos, V.; Michot, C.; Rodriguez, D.; Hubert, L.; Saillour, Y.; Labrune, P.; De Laveaucoupet, J.; Brunelle, F.; Amiel, J.; Lyonnet, S.; et al. Mutations of TSEN and CASK genes are prevalent in pontocerebellar hypoplasias type 2 and 4. Brain 2011, 135, e199.

- Van Dijk, T.; Barth, P.; Baas, F.; Reneman, L. Postnatal Brain Growth Patterns in Pontocerebellar Hypoplasia. Neuropediatrics 2021, 52, 163–169.

- Moog, U.; Bierhals, T.; Brand, K.; Bautsch, J.; Biskup, S.; Brune, T.; Denecke, J.; de Die-Smulders, C.E.; Evers, C.; Hempel, M.; et al. Phenotypic and molecular insights into CASK-related disorders in males. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2015, 10, 44.

- Mukherjee, K.; Patel, P.A.; Rajan, D.S.; LaConte, L.E.W.; Srivastava, S. Survival of a male patient harboring CASK Arg27Ter mutation to adolescence. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2020, 8, e1426.

- Nuovo, S.; Micalizzi, A.; Romaniello, R.; Arrigoni, F.; Ginevrino, M.; Casella, A.; Serpieri, V.; D’Arrigo, S.; Briguglio, M.; Salerno, G.G.; et al. Refining the mutational spectrum and gene–phenotype correlates in pontocerebellar hypoplasia: Results of a multicentric study. J. Med. Genet. 2021.

- Nakamura, K.; Nishiyama, K.; Kodera, H.; Nakashima, M.; Tsurusaki, Y.; Miyake, N.; Matsumoto, N.; Saitsu, H.; Jinnou, H.; Ohki, S.; et al. A de novo CASK mutation in pontocerebellar hypoplasia type 3 with early myoclonic epilepsy and tetralogy of Fallot. Brain Dev. 2014, 36, 272–273.

- Ilieva, H.; Polymenidou, M.; Cleveland, D.W. Non–cell autonomous toxicity in neurodegenerative disorders: ALS and beyond. J. Cell Biol. 2009, 187, 761–772.

- Pacheva, I.H.; Todorov, T.; Ivanov, I.; Tartova, D.; Gaberova, K.; Todorova, A.; Dimitrova, D. TSEN54 Gene-Related Pontocerebellar Hypoplasia Type 2 Could Mimic Dyskinetic Cerebral Palsy with Severe Psychomotor Retardation. Front. Pediatr. 2018, 6, 1.

More

Information

Subjects:

Neurosciences

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

986

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

20 Apr 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No