Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Arman Tsaturyan | -- | 2988 | 2022-04-17 13:57:04 | | | |

| 2 | Dean Liu | -1 word(s) | 2987 | 2022-04-18 04:20:22 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Tsaturyan, A.; , .; Liatsikos, E. Different Nerve-Sparing Techniques during Radical Prostatectomy. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21852 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Tsaturyan A, , Liatsikos E. Different Nerve-Sparing Techniques during Radical Prostatectomy. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21852. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Tsaturyan, Arman, , Evangelos Liatsikos. "Different Nerve-Sparing Techniques during Radical Prostatectomy" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21852 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Tsaturyan, A., , ., & Liatsikos, E. (2022, April 17). Different Nerve-Sparing Techniques during Radical Prostatectomy. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21852

Tsaturyan, Arman, et al. "Different Nerve-Sparing Techniques during Radical Prostatectomy." Encyclopedia. Web. 17 April, 2022.

Copy Citation

Nerve-sparing technique during RP has a major impact to both oncological and functional outcomes of the procedure and various different techniques have been developed aiming to optimize its outcomes. Nerve-sparing techniques can be distinguished based on the fascial planes of dissection (intrafascial, interfascial or extrafascial), the direction of dissection (retrograde or antegrade), the timing of the neurovascular bundle dissection off the prostate (early vs. late release), the use of cautery, the application of traction and the number of the neurovascular bundles which are preserved.

prostate cancer

radical prostatectomy

nerve-sparing

techniques

1. Basic Principles of NS Techniques

NS techniques can be distinguished depending on the fascial planes which are dissected (intrafascial, interfascial or extrafascial), the direction used during dissection (antegrade, retrograde or a combination of two), the timing of the NVB release off the prostate (before or after manipulations on the prostatic vascular pedicles), the use of cautery (thermal or athermal), the application of traction (traction-free or non-traction-free techniques) and the number of the NVBs which are preserved (unilateral or bilateral NS). Transection, cautery, crush and traction are underlying mechanisms by which the cavernous nerves can be injured during manipulations, and many NS techniques have been developed in order to avoid one or more of them [1]. Despite this rough categorization, several alternative NS techniques have been developed which cannot be integrated into one of the categories described above.

2. The Fascial Planes for NS

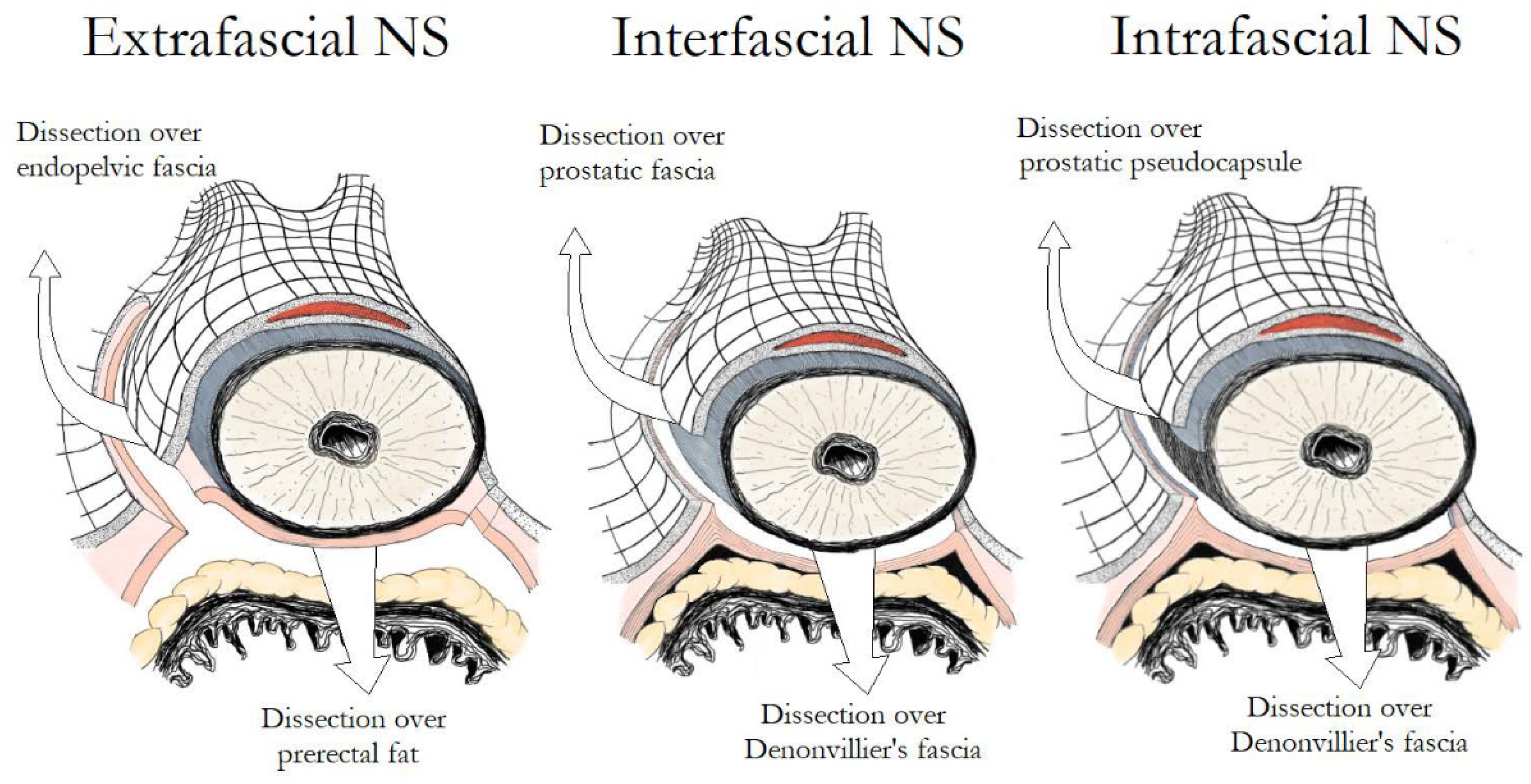

The prostate and the bladder are covered by a multilayer fascia called the endopelvic fascia, which is linked with both of them by collagen fibers. At the level of the prostate, the endopelvic fascia has an inner part overlying the prostate (prostatic fascia) and an outer part (Levator fascia or Lateral Pelvic Fascia). Posteriorly, the prostate and the seminal vesicles are covered by the Denonvilliers’ fascia, which laterally merges with the endopelvic fascia. Finally, a layer of fibromuscular smooth muscle located between the prostatic glandular units and the periprostatic connective tissue, along with vessels and nerves, constitute the prostatic capsule [2]. Based on the exact fascial plane of dissection, three different NS techniques can be described (Figure 1). In extrafascial NS, dissection is performed under the Denonvilliers’ fascia, as evidenced by the presence of perirectal fat on the posterior aspect of the dissection plane. In interfascial NS, the prostatic fascia is retained intact and dissection is performed within the plane between the prostatic fascia and the lateral pelvic fascia, which extends posteriorly as the plane between the prostatic fascia and the Denonvilliers’ fascia. Although the original NS procedure described by Walsh was performed using the interfascial technique, the discovery of supplementary nerve fibers on the anterolateral surface of the prostate promoted the development of the intrafascial technique in an attempt to preserve them [3]. In intrafascial NS, dissection is performed within the plane between the prostatic capsule and the prostatic fascia. At the end of the intrafascial dissection, no additional tissue over the prostate is identified.

Figure 1. Main differences in fascial development between extrafascial, interfascial and intrafascial nerve-sparing.

2.1. Intrafascial vs. Interfascial NS

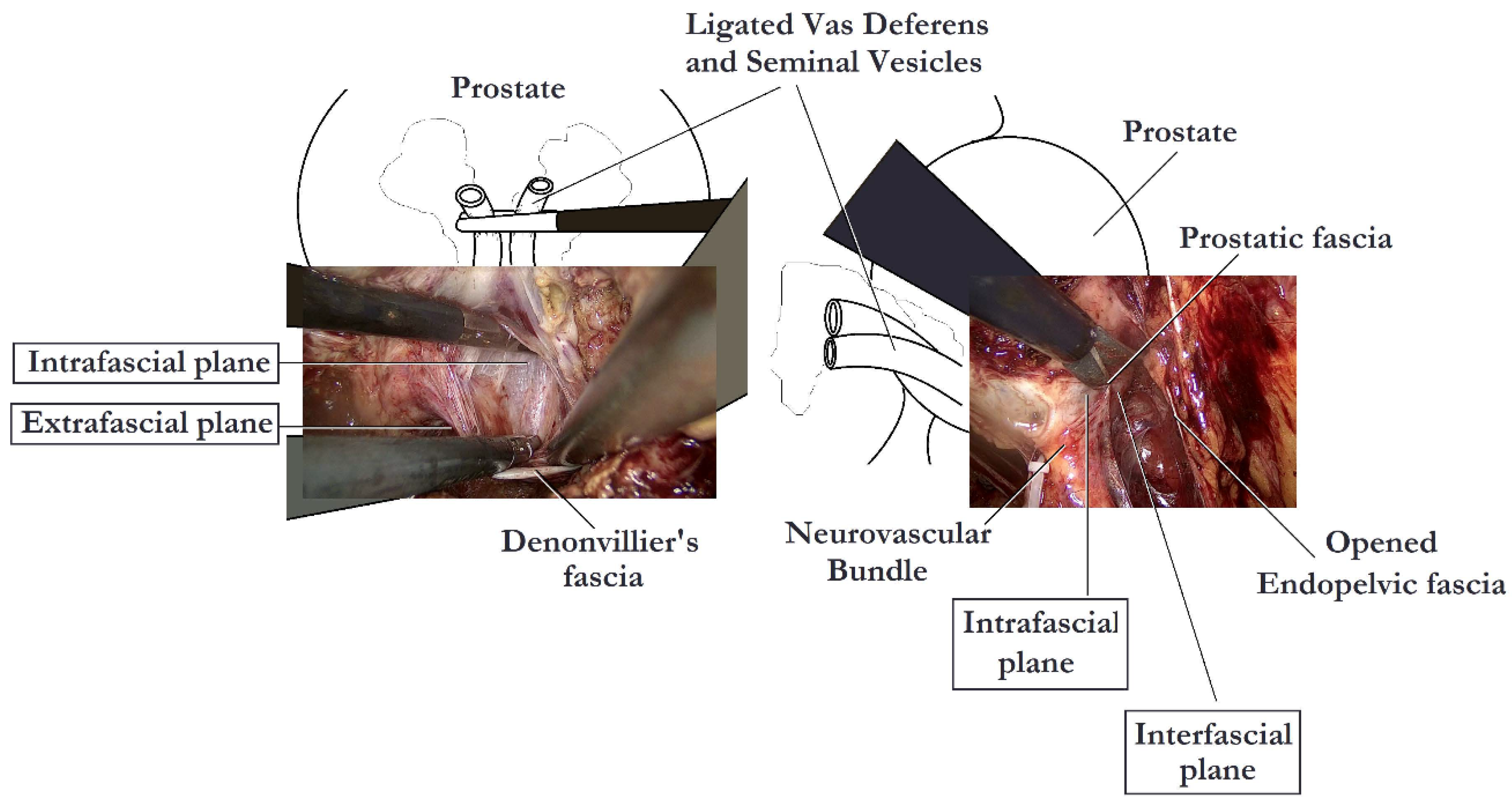

Several studies have examined the impact of different fascial planes of NS on the functional outcomes of RP. Khoder et al. conducted a prospective study, in which 430 patients were included, comparing open complete intrafascial with interfascial RP. They concluded that the intrafascial prostatectomy offers better functional results in comparison to the interfascial approach, without compromising the oncological results a year after the procedure [4]. In another study including 147 patients, Potdevin et al. compared the outcomes of intrafascial versus interfascial NS in robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP). The authors observed a higher potency rate and a shortened time of the return of continence following the intrafascial technique. Nevertheless, the positive surgical margin rates were higher in patients with pT3 disease in the intrafascial group [5]. Stolzenburg et al. compared the outcomes for interfascial and intrafascial NS endoscopic extraperitoneal RP, coming to the conclusion that the intrafascial technique is associated with significantly better potency in patients <55 years of age at 12 months and in patients 55–65 years of age at 6 and 12 months, with probably limited effect on the oncological outcomes. Moreover, the intrafascial technique was also associated with significantly improved continence rates at 3 and 6 months after surgery as compared with the interfascial approach [3]. Although many studies report better outcomes following the intrafascial technique, the oncological safety of this procedure has been called into question. Curto et al. found a positive surgical margin rate of 30.7%, associated with the intrafascial approach, a rate much higher than that of other interfascial series [6]. In contrast, Wang et al. noted that the intrafascial NS, when cases are carefully selected, could offer an acceptable or, at least, equivalent positive surgical margin rate compared with the conventional interfascial approach [7]. In a recent meta-analysis, performed by Weng et al., the intrafascial technique has proven to be superior to the interfascial technique in terms of functional outcomes, likely due to lesser nerve damage. The research demonstrated better continence at 6 months and 36 months and better potency recovery at 6 months and 12 months postoperatively, associated with the intrafascial approach. Surprisingly, cancer control was also better with the intrafascial technique, possibly because patients in the interfascial group presented higher-risk cancer than patients in the intrafascial group [8]. The key steps of intrafascial NS are depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Nerve-sparing intrafascial laparoscopic radical prostatectomy.

2.2. Extrafascial vs. Non-Extrafascial (Intrafascial and Interfascial) NS

Shikanov et al. compared 110 cases of bilateral extrafascial NS versus 703 cases of interfascial NS. They observed significantly better sexual function in patients undergoing bilateral interfascial NS, while in lower-risk patients, bilateral interfascial NS did not result in significantly higher positive surgical margins rates [9]. Zhao et al. in a meta-analysis including 2096 patients from 7 eligible studies, compared the oncological and functional outcomes of intrafascial with non-intrafascial RP (including interfascial, extrafascial and no nerve-sparing approaches) in patients with low-risk localized prostate cancer. The meta-analysis demonstrated that the oncological outcomes were similar between the two groups, while the intrafascial approach was associated with lower postoperative complication rates, higher continence rates at 3 months and higher potency rates at 6 and 12 months following surgery, as compared to the non-intrafascial approaches [10].

3. Different NS Grading Systems

Various alternative grading systems have been proposed to describe the different degrees of NS. The intrafascial plane corresponds to the maximal extent of NS, while the extrafascial plane corresponds to the minimal extent. Montorsi et al. divided NS into full, partial and minimal as matching intrafascial, interfascial and partial extrafascial dissections, respectively [11]. Tewari et al. proposed a new 4-degree stratification for the preservation of the neurovascular bundles, using the veins which are situated on the lateral aspect of the prostate as landmarks. According to them, grade 1 matches a complete intrafascial dissection and is a dissection between the periprostatic veins and the pseudocapsule of the prostate. Grade 2 matches an interfascial dissection and is a dissection performed just over the veins, while grade 3 dissection leaves more tissue over the veins and the prostate. Finally, grade 4 matches an extrafascial dissection [12]. Schatloff et al. proposed a 5-degree stratification for the definition of the dissection planes, using the “landmark artery” (LA), which runs on the lateral aspect of the prostate, as a reference point. The LA can be recognized, intraoperatively, in up to 73% of cases. A grade 5 dissection, during which the prostate and the NVBs can be separated without the need for sharp dissection, matches a maximal NS (complete intrafascial dissection) and is performed medially to the LA just outside the prostatic fascia. A grade 4 dissection is performed using sharp dissection in a plane between the LA and the prostatic pseudocapsule across the NVB, while in a grade 3 dissection, the plane of NS is created laterally to the LA, and thus the artery is clipped at the level of the prostate pedicle. Finally, for a grade 2 dissection, NS is performed several millimeters laterally to the artery, while for a grade 1 dissection, an extrafascial dissection is performed and the NVBs are not spared (Figure 1) [13]. A summary of the different grading systems is demonstrated in Table 1.

Table 1. Different nerve-sparing grading systems.

| Nerve-Sparing Grading System | References | Anatomical Landmark | Number of Grades | Description of Different Grades |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fascial planes | Stolzenburg et al. [3] | Periprostatic fasciae | 3 |

|

| Extent of nerve-sparing | Montorsi et al. [11] | Neurovascular bundles | 3 |

|

| 4-degree approach for preservation of the neurovascular bundles | Tewari et al. [12] | The veins which are situated on the lateral aspect of the prostate | 4 |

|

| 5-degree approach for the definition of the dissection planes | Schatloff et al. [13] | The “landmark artery” (LA), which runs on the lateral aspect of the prostate | 5 |

|

3. The Direction of NS

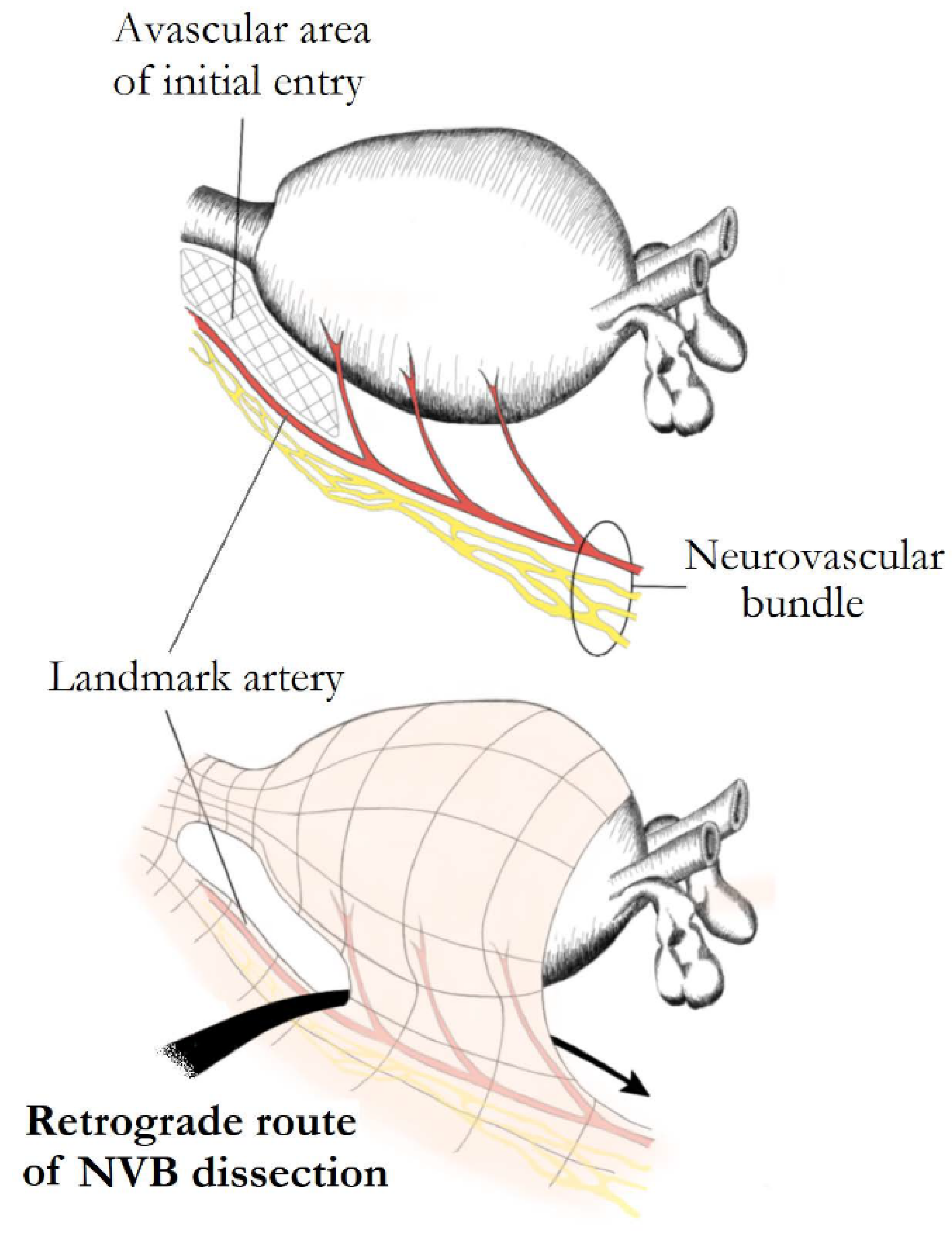

The conventional open retropubic RP, proposed by Walsh, includes a completely retrograde NS dissection. The direction of dissection is from the prostatic apex towards the base, while the vascular pedicles are taken last after the dissection of the NVBs. A similar retrograde approach has also been described in laparoscopic and robotic surgery. The retrograde approach has the advantage of early recognition and release of the NVBs from the prostate, before controlling the posterior pedicle [1][14]. Patel et al. described their technique of early retrograde release of the NVBs during RARP in an athermal way with minimization of traction. In order to perform this approach, the LA must first be recognized in the lateral aspect of the prostate. A plane is developed between the LA and the prostate, which is continued posteriorly, and then the dissection proceeds in a retrograde way towards the base of the prostate (Figure 3). Prostatic pedicles are clipped last, resulting in a natural traction-free release of the NVBs off the prostate. Describing their results in 397 patients, they reported that 87.7% of patients with Sexual Health Inventory for Men (SHIM) >21, and 73% with SHIM between 17 and 21 preoperatively, were potent with or without the use of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors, after a 3-month follow-up [2][13][14].

Figure 3. Retrograde nerve-sparing. After posterior prostatic dissection, an avascular area at the lateral margins of the prostatic apex overlying the landmark artery (LA) of neurovascular bundles is identified and used as the initial point of dissection. The bundles are further dissected in a retrograde fashion. Preservation of the LA ensures complete preservation of the ipsilateral main neural branch.

Conversely, in the antegrade approach, the direction of the dissection is from the prostatic base towards the apex with the vascular pedicles being transected first [1][14]. Antegrade NS is a widely used practice among laparoscopic and robotic surgeons. The procedure starts with gentle upward traction of the vas and seminal vesicles in order to reveal the prostatic pedicles. Counter traction of the prostate exposes the triangular space between the lateral pelvic fascia, the Denonvilliers’ fascia and the prostatic fascia and either the interfascial or the intrafascial dissection is performed [13][14]. An antegrade approach has been described in open surgery as well [15][16]. According to Carini et al., open antegrade NS constitutes a less challenging procedure with similar results to those reported by the retrograde approach [15]. Finally, a partial retrograde approach has been described which preserves the advantages of the antegrade NS, but takes the vascular pedicles last as in the retrograde NS [1].

Regarding the impact of different directions of NS on functional outcomes, a questionnaire-based assessment demonstrated that 67% of patients undergoing retrograde, and 76% of patients undergoing antegrade NS laparoscopic RP, were able to engage in sexual intercourse (with or without phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors) postoperatively [17]. On the contrary, in a nonrandomized comparative study, Ko et al. reported that, in patients with normal preoperative erectile function, a retrograde direction of nerve-sparing during RARP was associated with significantly higher potency rates at 3, 6 and 9 months compared with an antegrade direction of NS, without compromising cancer control [18].

4. The Functional Impact of Using Energy and Nerve Traction during NS RP

The potential injury and functional recovery of the nerves depend first of all on the nature of the nerves. While some studies have failed to identify myelinated nerve fibers originating from inferior hypogastric plexus [19], others have shown both myelinated and unmyelinated components in prostatic nerves [20][21]. There are several classifications used for evaluating and terming nerve injuries [22]. Based on Seddon’s classification, the nerve injuries can be divided into 3 types: neurapraxia, axonotmesis and neurotmesis [23]. Neurapraxia is a first-degree injury, commonly caused by mechanic blunt trauma to the nerves. The recovery after this injury may take as long as 12 weeks. Axonotmesis, the second-degree injury, is termed so due to axonal injury, yet preserving the surrounding connective tissue. Depending on the injury distance and with the axonal growth rate of 1 mm/day delayed nerve recovery, up to 24 months may be required. Neurotmesis is the most severe injury of the nerve commonly resulting in an irreversible loss of nerve function [24].

The nerves of NVBs, are sensitive to thermal energy which is diffused during current use in adjacent structures [2]. Suspecting that thermal injury of NVBs could be responsible for the postoperative loss of potency, many investigators tried to develop totally athermal methods. Theoretically, cautery-free techniques manage adequate hemostasis, while improving the return of erectile function by minimizing injury to the NVBs. Vascular clips, suture ligation and bulldog clamps with suturing constitute the most common cautery-free techniques, used during prostatic vascular pedicle manipulations [1]. In addition, several hemostatic agents have been used for the purpose of controlling bleeding. Although hemostatic agents were used in Ahlering’s initial report, their inability to manage hemostasis in 15% of the cases led to their substitution by suture ligation [25]. Gill et al. also reported problems with FloSealTM in their laparoscopic RP series, frequently requiring secondary clip placement [26]. Moreover, usage of bioadhesives near the NVBs can potentially injure them, as a result of a lymphocytic inflammatory reaction and fibrosis [1].

The impact of different hemostatic energy sources on the integrity of NVBs was initially documented in the experimental setting. Ong et al. evaluated cavernous nerve function on 12 dogs, which were divided into 4 groups, each subjected to NS using conventional dissection with suture ligatures, monopolar electrosurgery, bipolar electrosurgery or ultrasonic shears, respectively. The authors observed that the use of energy sources near the NVBs was associated with a considerable decrease in erectile response both acutely and after 2 weeks; while following conventional dissection with suture ligatures, the erectile response to nerve stimulation was unaffected [27]. It has been also shown that monopolar and bipolar energy have an almost similar risk of heat generation and potential tissue injury [28]. However, a decreased risk of nerve injury with bipolar energy can be observed when cut and caterization is performed, so-called touch cautery, due to preservation of adjacent blood flow [29].

In accordance with these findings, several clinical studies confirmed the importance of athermal dissection. Ahlering et al. described a clipless cautery-free approach for NS, using bulldog vascular clamps and sutures, and reported a nearly 5-fold rate of improvement in potency recovery as compared to a group where NS took place using cautery. Defining potency as “erections hard enough for vaginal penetration with or without the use of PDE-5 inhibitors” in the cautery group, 14.7% of patients were potent after 9 months and 63.2% after 24 months, as compared to 69.8% (after 9 months) and 92% (after 24 months) for the cautery-free group [25][30][31]. Likewise, Chien et al. described analogous findings during a completely athermal RARP procedure, reporting a faster return and preservation of sexual function. In their modified clipless antegrade NS technique, after developing the posterior plane of the prostate towards the apex in the midline, they released the vascular pedicles and the NVBs in a medial-to-lateral direction using a combination of sharp and cold scissors. They only used judiciously bipolar cautery, avoiding clips and monopolar cautery. According to them, the potency rates after this approach, using a 36-item health survey questionnaire, were 47%, 54%, 66% and 69% after 1, 3, 6 and 12 months, respectively [32]. Gill et al. using real-time Doppler transrectal ultrasound showed that bulldog clamping of the lateral vascular pedicles was associated with preservation of blood flow in the NVBs and restriction of the need for cautery [26]. Finally, Fagin et al. compared three different NS techniques (selective bipolar cautery, an athermal “clip and peel” posterior dissection technique and an athermal combined anterior and posterior dissection technique with clips and sharp dissection). The authors reported better recovery of potency with the athermal techniques, with the combined anterior and posterior approach being the superior of the two athermal techniques. This approach was also associated with the lowest positive margin rates [33].

Regarding the impact of different energy sources on functional outcomes, the available data are limited. Pagliarulo et al. compared the athermal and the ultrasonic NS laparoscopic RP procedures, coming to the conclusion that the use of an ultrasonic device did not have a negative impact on long-term potency and continence outcomes, nor did it lead to early biochemical recurrence, as compared to the athermal approach [34]. Pastore et al. performed a prospective randomized study, comparing radiofrequency and ultrasound scalpels on functional outcomes of laparoscopic RP and documented that the radiofrequency scalpel was associated with better functional outcomes [35].

With regard to the impact of traction on the integrity of NVBs, many studies have documented the positive effects of traction-free techniques. Kowalczyk et al. observing 610 patients who underwent RARP, 342 of whom were with avoidance of countertraction of the NVBs during NS, reported earlier sexual function recovery in the traction-free group (45% versus 28% at five months). However, potency rates were the same among the two groups at 1 year [36]. Similar results were reported by Masterson et al., who modified their technique in order to avoid countertraction of the NVBs during RARP and observed improved rates of erectile function recovery during a six-month period [37]. Finally, Mattei et al. presented the results of their lateral approach for the interfascial dissection of the NVBs without tension and any use of electrocautery. In their study, one week after catheter removal, 80% of patients had complete early urinary continence and a high rate of patients reported spontaneous erections or penile tumescence, while at the 4-month follow-up visit, 92.4% of patients were completely continent and 65% of patients were considered potent [38].

References

- Rodriguez, E.; Melamud, O.; Ahlering, T.E. Nerve-sparing techniques in open and laparoscopic prostatectomy. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2008, 8, 475–479.

- Chauhan, S.; Coelho, R.F.; Rocco, B.; Palmer, K.J.; Orvieto, M.A.; Patel, V.R. Techniques of nerve-sparing and potency outcomes following robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy. Int. Braz. J. Off. J. Braz. Soc. Urol. 2010, 36, 259–272.

- Stolzenburg, J.U.; Kallidonis, P.; Do, M.; Dietel, A.; Hafner, T.; Rabenalt, R.; Sakellaropoulos, G.; Ganzer, R.; Paasch, U.; Horn, L.C.; et al. A comparison of outcomes for interfascial and intrafascial nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. Urology 2010, 76, 743–748.

- Khoder, W.Y.; Waidelich, R.; Buchner, A.; Becker, A.J.; Stief, C.G. Prospective comparison of one year follow-up outcomes for the open complete intrafascial retropubic versus interfascial nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy. SpringerPlus 2014, 3, 335.

- Potdevin, L.; Ercolani, M.; Jeong, J.; Kim, I.Y. Functional and oncologic outcomes comparing interfascial and intrafascial nerve sparing in robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomies. J. Endourol. 2009, 23, 1479–1484.

- Curto, F.; Benijts, J.; Pansadoro, A.; Barmoshe, S.; Hoepffner, J.L.; Mugnier, C.; Piechaud, T.; Gaston, R. Nerve sparing laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: Our technique. Eur. Urol. 2006, 49, 344–352.

- Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Guo, J.; Chen, H.; Weng, X.; Liu, X. Oncological safety of intrafascial nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy compared with conventional process: A pooled review and meta-regression analysis based on available studies. BMC Urol. 2019, 19, 41.

- Weng, H.; Zeng, X.T.; Li, S.; Meng, X.Y.; Shi, M.J.; He, D.L.; Wang, X.H. Intrafascial versus interfascial nerve sparing in radical prostatectomy for localized prostate cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11454.

- Shikanov, S.; Woo, J.; Al-Ahmadie, H.; Katz, M.H.; Zagaja, G.P.; Shalhav, A.L.; Zorn, K.C. Extrafascial versus interfascial nerve-sparing technique for robotic-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy: Comparison of functional outcomes and positive surgical margins characteristics. Urology 2009, 74, 611–616.

- Zhao, Z.; Zhu, H.; Yu, H.; Kong, Q.; Fan, C.; Meng, L.; Liu, C.; Ding, X. Comparison of intrafascial and non-intrafascial radical prostatectomy for low risk localized prostate cancer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17604.

- Montorsi, F.; Wilson, T.G.; Rosen, R.C.; Ahlering, T.E.; Artibani, W.; Carroll, P.R.; Costello, A.; Eastham, J.A.; Ficarra, V.; Guazzoni, G.; et al. Best practices in robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: Recommendations of the Pasadena Consensus Panel. Eur. Urol. 2012, 62, 368–381.

- Tewari, A.K.; Srivastava, A.; Huang, M.W.; Robinson, B.D.; Shevchuk, M.M.; Durand, M.; Sooriakumaran, P.; Grover, S.; Yadav, R.; Mishra, N.; et al. Anatomical grades of nerve sparing: A risk-stratified approach to neural-hammock sparing during robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP). BJU Int. 2011, 108, 984–992.

- Tavukcu, H.H.; Aytac, O.; Atug, F. Nerve-sparing techniques and results in robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Investig. Clin. Urol. 2016, 57, S172–S184.

- Kumar, A.; Patel, V.R.; Panaiyadiyan, S.; Seetharam Bhat, K.R.; Moschovas, M.C.; Nayak, B. Nerve-sparing robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: Current perspectives. Asian J. Urol. 2021, 8, 2–13.

- Carini, M.; Masieri, L.; Minervini, A.; Lapini, A.; Serni, S. Oncological and functional results of antegrade radical retropubic prostatectomy for the treatment of clinically localised prostate cancer. Eur. Urol. 2008, 53, 554–561.

- Carrerette, F.B.; Carvalho, E.; Machado, H.; Freire, F.C.; Damiao, R. Open anterograde anatomic radical retropubic prostatectomy technique: Description of the first fiftyfive procedures. Int. Braz. J. Off. J. Braz. Soc. Urol. 2019, 45, 1071–1072.

- Rassweiler, J.; Wagner, A.A.; Moazin, M.; Gozen, A.S.; Teber, D.; Frede, T.; Su, L.M. Anatomic nerve-sparing laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: Comparison of retrograde and antegrade techniques. Urology 2006, 68, 587–591.

- Ko, Y.H.; Coelho, R.F.; Sivaraman, A.; Schatloff, O.; Chauhan, S.; Abdul-Muhsin, H.M.; Carrion, R.J.; Palmer, K.J.; Cheon, J.; Patel, V.R. Retrograde versus antegrade nerve sparing during robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: Which is better for achieving early functional recovery? Eur. Urol. 2013, 63, 169–177.

- Alsaid, B.; Karam, I.; Bessede, T.; Abdlsamad, I.; Uhl, J.F.; Delmas, V.; Benoit, G.; Droupy, S. Tridimensional computer-assisted anatomic dissection of posterolateral prostatic neurovascular bundles. Eur. Urol. 2010, 58, 281–287.

- Reeves, F.; Battye, S.; Borin, J.F.; Corcoran, N.M.; Costello, A.J. High-resolution Map of Somatic Periprostatic Nerves. Urology 2016, 97, 160–165.

- Yoon, Y.; Jeon, S.H.; Park, Y.H.; Jang, W.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, K.H. Visualization of prostatic nerves by polarization-sensitive optical coherence tomography. Biomed. Opt. Express 2016, 7, 3170–3183.

- Kaya, Y.; Sarikcioglu, L. Sir Herbert Seddon (1903–1977) and his classification scheme for peripheral nerve injury. Child’s Nerv. Syst. 2015, 31, 177–180.

- Seddon, H.J. Three types of nerve injury. Brain 1943, 66, 237–288.

- Chhabra, A.; Ahlawat, S.; Belzberg, A.; Andreseik, G. Peripheral nerve injury grading simplified on MR neurography: As referenced to Seddon and Sunderland classifications. Indian J. Radiol. Imaging 2014, 24, 217–224.

- Ahlering, T.E.; Eichel, L.; Chou, D.; Skarecky, D.W. Feasibility study for robotic radical prostatectomy cautery-free neurovascular bundle preservation. Urology 2005, 65, 994–997.

- Gill, I.S.; Ukimura, O.; Rubinstein, M.; Finelli, A.; Moinzadeh, A.; Singh, D.; Kaouk, J.; Miki, T.; Desai, M. Lateral pedicle control during laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: Refined technique. Urology 2005, 65, 23–27.

- Ong, A.M.; Su, L.M.; Varkarakis, I.; Inagaki, T.; Link, R.E.; Bhayani, S.B.; Patriciu, A.; Crain, B.; Walsh, P.C. Nerve sparing radical prostatectomy: Effects of hemostatic energy sources on the recovery of cavernous nerve function in a canine model. J. Urol. 2004, 172, 1318–1322.

- Khan, F.; Rodriguez, E.; Finley, D.S.; Skarecky, D.W.; Ahlering, T.E. Spread of thermal energy and heat sinks: Implications for nerve-sparing robotic prostatectomy. J. Endourol. 2007, 21, 1195–1198.

- Hofmann, M.; Huang, E.; Huynh, L.M.; Kaler, K.; Vernez, S.; Gordon, A.; Morales, B.; Skarecky, D.; Ahlering, T.E. Retrospective Concomitant Nonrandomized Comparison of “Touch” Cautery versus Athermal Dissection of the Prostatic Vascular Pedicles and Neurovascular Bundles During Robot-assisted Radical Prostatectomy. Eur. Urol. 2022, 81, 104–109.

- Ahlering, T.E.; Rodriguez, E.; Skarecky, D.W. Overcoming obstacles: Nerve-sparing issues in radical prostatectomy. J. Endourol. 2008, 22, 745–750.

- Ahlering, T.E.; Skarecky, D.; Borin, J. Impact of cautery versus cautery-free preservation of neurovascular bundles on early return of potency. J. Endourol. 2006, 20, 586–589.

- Chien, G.W.; Mikhail, A.A.; Orvieto, M.A.; Zagaja, G.P.; Sokoloff, M.H.; Brendler, C.B.; Shalhav, A.L. Modified clipless antegrade nerve preservation in robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy with validated sexual function evaluation. Urology 2005, 66, 419–423.

- Fagin, R. Da Vinci prostatectomy: Athermal nerve sparing and effect of the technique on erectile recovery and negative margins. J. Robot. Surg. 2007, 1, 139–143.

- Pagliarulo, V.; Alba, S.; Gallone, M.F.; Zingarelli, M.; Lorusso, A.; Minafra, P.; Ludovico, G.M.; Di Stasi, S.; Ditonno, P. Athermal versus ultrasonic nerve-sparing laparoscopic radical prostatectomy: A comparison of functional and oncological outcomes. World J. Urol. 2021, 39, 1453–1462.

- Pastore, A.L.; Palleschi, G.; Silvestri, L.; Leto, A.; Sacchi, K.; Pacini, L.; Petrozza, V.; Carbone, A. Prospective randomized study of radiofrequency versus ultrasound scalpels on functional outcomes of laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. J. Endourol. 2013, 27, 989–993.

- Kowalczyk, K.J.; Huang, A.C.; Hevelone, N.D.; Lipsitz, S.R.; Yu, H.Y.; Ulmer, W.D.; Kaplan, J.R.; Patel, S.; Nguyen, P.L.; Hu, J.C. Stepwise approach for nerve sparing without countertraction during robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: Technique and outcomes. Eur. Urol. 2011, 60, 536–547.

- Masterson, T.A.; Serio, A.M.; Mulhall, J.P.; Vickers, A.J.; Eastham, J.A. Modified technique for neurovascular bundle preservation during radical prostatectomy: Association between technique and recovery of erectile function. BJU Int. 2008, 101, 1217–1222.

- Mattei, A.; Naspro, R.; Annino, F.; Burke, D.; Guida, R., Jr.; Gaston, R. Tension and energy-free robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy with interfascial dissection of the neurovascular bundles. Eur. Urol. 2007, 52, 687–694.

More

Information

Subjects:

Urology & Nephrology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

2.5K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

18 Apr 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No