| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yousef Yari Kamrani | -- | 3397 | 2022-04-14 15:15:33 | | | |

| 2 | Amina Yu | -1 word(s) | 3396 | 2022-04-15 04:55:53 | | |

Video Upload Options

Plants undergo diurnal oscillations that are generated and maintained by an endogenous system known as the circadian clock. The circadian system is a complex, inter-connected, and reciprocally regulated network. The core oscillator consists of many coupled feedback loops in plants. Circadian rhythms are governed by a molecular clock system that synchronizes plant function with daily light and temperature cycles to maintain homeostasis, and the efficient functioning of plants depends on the proper operation of the circadian clock system. In fact, many plant processes follow a rhythmic sinusoidal pattern over the course of a 24 h period, in perfect sync with the diurnal cycle. These oscillations persist in the absence of environmental stimuli (under continuous light and constant temperature), and can be sustained for several weeks.

1. Circadian Clock Plays a Central Role in Plant Fitness

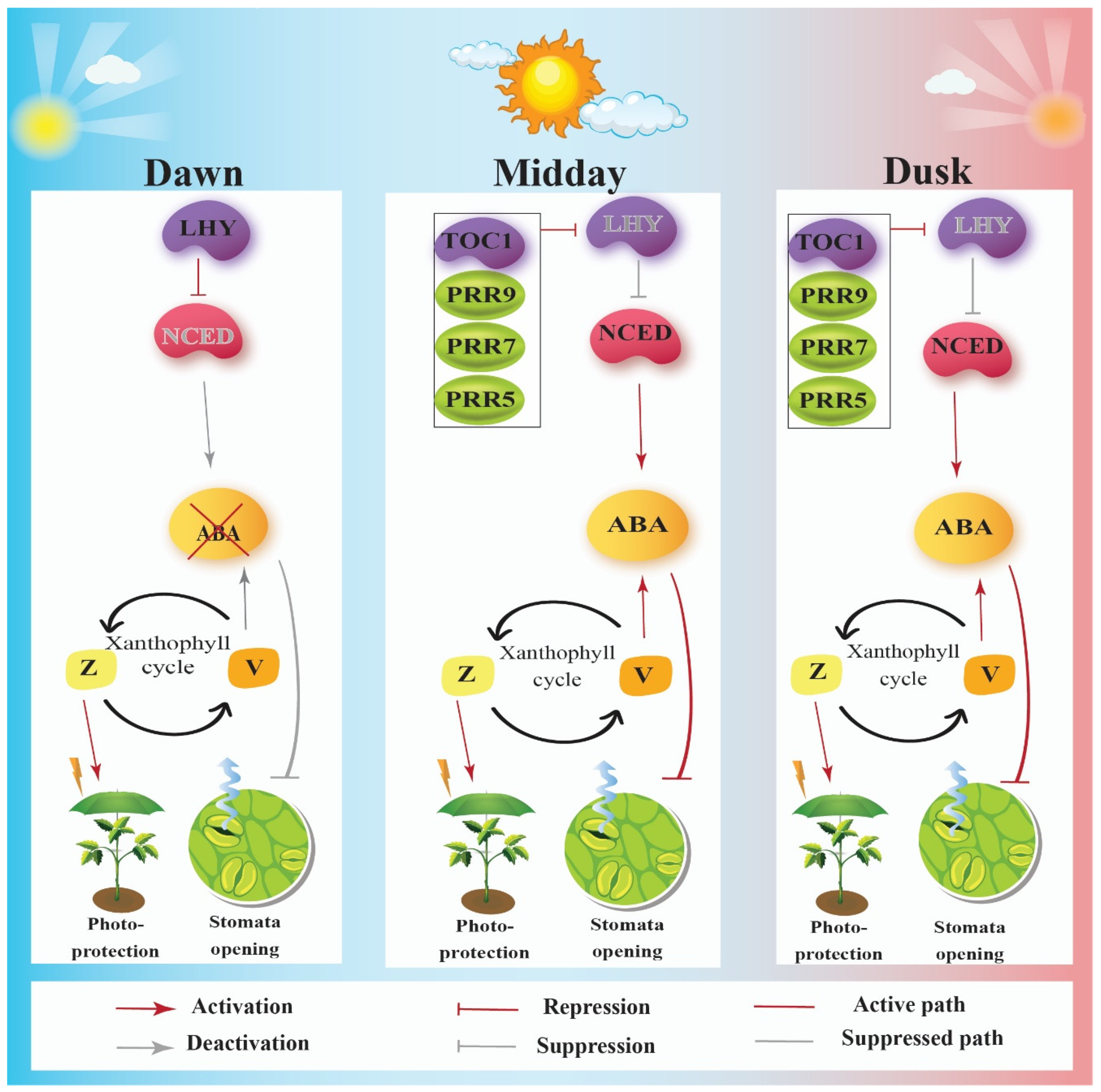

2. Circadian Clock Enhances Fitness by Controlling Photoprotection via the Xanthophyll Cycle

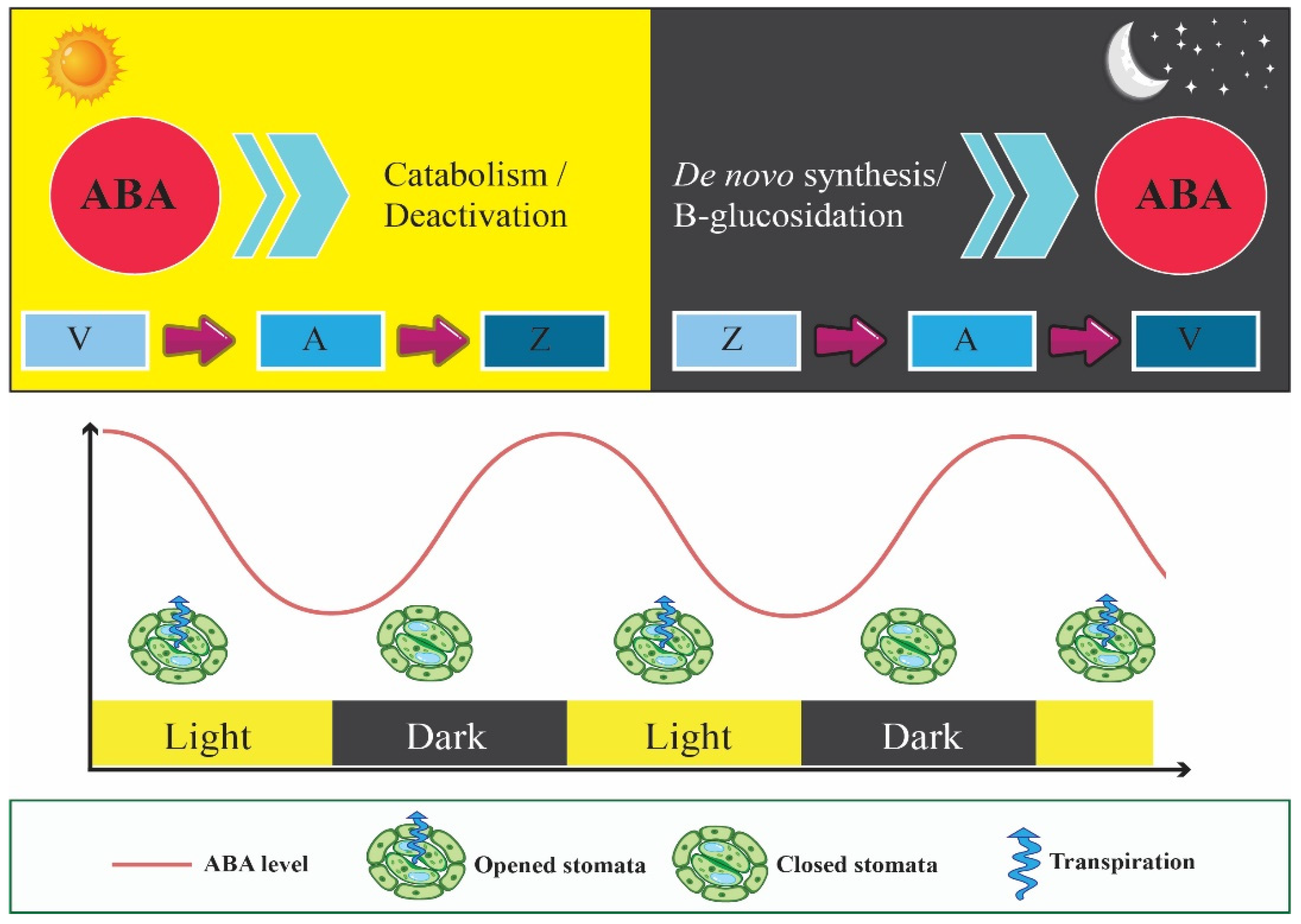

3. Circadian Clock Enhances Fitness by Assisting Adaptive Stomatal Movements

4. Circadian Clock Enhances Fitness by Controlling WUE through Affecting Stomatal Movements

5. Circadian Clock Enhances Fitness by Improving Plant Drought-Stress Responses

References

- Yerushalmi, S.; Yakir, E.; Green, R.M. Circadian clocks and adaptation in Arabidopsis. Mol. Ecol. 2011, 20, 1155–1165.

- Chen, P.; Liu, P.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, L.; Hao, X.; Liu, L.; Bu, C.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, D.; Song, Y. Dynamic physiological and transcriptome changes reveal a potential relationship between the circadian clock and salt stress response in Ulmus pumila. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2022, 297, 303–317.

- Harmer, S.L.; Hogenesch, J.B.; Straume, M.; Chang, H.-S.; Han, B.; Zhu, T.; Wang, X.; Kreps, J.A.; Kay, S.A. Orchestrated Transcription of Key Pathways in Arabidopsis by the Circadian Clock. Science 2000, 290, 2110–2113.

- Gendron, J.M.; Pruneda-Paz, J.L.; Doherty, C.J.; Gross, A.M.; Kang, S.E.; Kay, S.A. Arabidopsis circadian clock protein, TOC1, is a DNA-binding transcription factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 3167–3172.

- Ferrari, C.; Proost, S.; Janowski, M.; Becker, J.; Nikoloski, Z.; Bhattacharya, D.; Price, D.; Tohge, T.; Bar-Even, A.; Fernie, A.; et al. Kingdom-wide comparison reveals the evolution of diurnal gene expression in Archaeplastida. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 737.

- Monnier, A.; Liverani, S.; Bouvet, R.; Jesson, B.; Smith, J.Q.; Mosser, J.; Corellou, F.; Bouget, F.Y. Orchestrated transcription of biological processes in the marine picoeukaryote Ostreococcus exposed to light/dark cycles. BMC Genom. 2010, 11, 192.

- Michael, T.P.; Mockler, T.C.; Breton, G.; McEntee, C.; Byer, A.; Trout, J.D.; Hazen, S.P.; Shen, R.; Priest, H.D.; Sullivan, C.M.; et al. Network discovery pipeline elucidates conserved time-of-day-specific cis-regulatory modules. PLoS Genet. 2008, 4, e14.

- Serrano-Bueno, G.; Romero-Campero, F.J.; Lucas-Reina, E.; Romero, J.M.; Valverde, F. Evolution of photoperiod sensing in plants and algae. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2017, 37, 10–17.

- Huner, N.P.A.; Oquist, G.; Hurry, V.M.; Krol, M.; Falk, S.; Griffith, M. Photosynthesis, photoinhibition and low temperature acclimation in cold tolerant plants. Photosynth. Res. 1993, 37, 19–39.

- Müller, P.; Li, X.P.; Niyogi, K.K. Non-photochemical quenching. A response to excess light energy. Plant Physiol. 2001, 125, 1558–1566.

- Niyogi, K.K. Photoprotection revisited: Genetic and molecular approaches. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 1999, 50, 333–359.

- Walters, R.G. Towards an understanding of photosynthetic acclimation. J. Exp. Bot. 2005, 56, 435–447.

- Davison, P.A.; Hunter, C.N.; Horton, P. Overexpression of β-carotene hydroxylase enhances stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Nature 2002, 418, 203–206.

- Hager, A.; Holocher, K. Localization of the xanthophyll-cycle enzyme violaxanthin de-epoxidase within the thylakoid lumen and abolition of its mobility by a (light-dependent) pH decrease. Planta 1994, 192, 581–589.

- Faure, S.; Turner, A.S.; Gruszka, D.; Christodoulou, V.; Davis, S.J.; Von Korff, M.; Laurie, D.A. Mutation at the circadian clock gene EARLY MATURITY 8 adapts domesticated barley (Hordeum vulgare) to short growing seasons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 8328–8333.

- McClung, C.R. Beyond Arabidopsis: The circadian clock in non-model plant species. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2013, 24, 430–436.

- Yarkhunova, Y.; Guadagno, C.R.; Rubin, M.J.; Davis, S.J.; Ewers, B.E.; Weinig, C. Circadian rhythms are associated with variation in photosystem II function and photoprotective mechanisms. Plant Cell Environ. 2018, 41, 2518–2529.

- Litthauer, S.; Battle, M.W.; Lawson, T.; Jones, M.A. Phototropins maintain robust circadian oscillation of PSII operating efficiency under blue light. Plant J. 2015, 83, 1034–1045.

- Galvez-Valdivieso, G.; Fryer, M.J.; Lawson, T.; Slattery, K.; Truman, W.; Smirnoff, N.; Asami, T.; Davies, W.J.; Jones, A.M.; Baker, N.R.; et al. The high light response in arabidopsis involves ABA signaling between vascular and bundle sheath cells W. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 2143–2162.

- Teng, K.; Li, J.; Liu, L.; Han, Y.; Du, Y.; Zhang, J.; Sun, H.; Zhao, Q. Exogenous ABA induces drought tolerance in upland rice: The role of chloroplast and ABA biosynthesis-related gene expression on photosystem II during PEG stress. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2014, 36, 2219–2227.

- Huang, J.; Zhao, X.; Chory, J. The Arabidopsis Transcriptome Responds Specifically and Dynamically to High Light Stress. Cell Rep. 2019, 29, 4186–4199.e3.

- Suzuki, N.; Miller, G.; Salazar, C.; Mondal, H.A.; Shulaev, E.; Cortes, D.F.; Shuman, J.L.; Luo, X.; Shah, J.; Schlauch, K.; et al. Temporal-spatial interaction between reactive oxygen species and abscisic acid regulates rapid systemic acclimation in plants. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 3553–3569.

- van Meeteren, U.; Aliniaeifard, S. Stomata and postharvest physiology. Postharvest Ripening Physiol. Crop. 2016, 1, 157–216.

- Hetherington, A.M.; Woodward, F.I. The role of stomata in sensing and driving environmental change. Nature 2003, 424, 901–908.

- Hubbard, K.E.; Webb, A.A.R. Circadian Rhythms in Stomata: Physiological and Molecular Aspects. In Rhythms in Plants; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 231–255. ISBN 9783319205175.

- Adams, S.; Grundy, J.; Veflingstad, S.R.; Dyer, N.P.; Hannah, M.A.; Ott, S.; Carré, I.A. Circadian control of abscisic acid biosynthesis and signalling pathways revealed by genome-wide analysis of LHY binding targets. New Phytol. 2018, 220, 893–907.

- Legnaioli, T.; Cuevas, J.; Mas, P. TOC1 functions as a molecular switch connecting the circadian clock with plant responses to drought. EMBO J. 2009, 28, 3745–3757.

- Pokhilko, A.; Mas, P.; Millar, A.J. Modelling the widespread effects of TOC1 signalling on the plant circadian clock and its outputs. BMC Syst. Biol. 2013, 7, 23.

- Correia, M.J.; Pereira, J.S.; Chaves, M.M.; Rodrigues, M.L.; Pacheco, C.A. ABA xylem concentrations determine maximum daily leaf conductance of field-grown Vitis vinifera L. plants. Plant Cell Environ. 1995, 18, 511–521.

- Snaith, P.J.; Mansfield, T.A. The circadian rhythm of stomatal opening: Evidence for the involvement of potassium and chloride fluxes. J. Exp. Bot. 1986, 37, 188–199.

- Dodd, A.N.; Salathia, N.; Hall, A.; Kévei, E.; Tóth, R.; Nagy, F.; Hibberd, J.M.; Millar, A.J.; Webb, A.A.R. Plant circadian clocks increase photosynthesis, growth, survival, and competitive advantage. Science 2005, 309, 630–633.

- Zhang, C.; Xie, Q.; Anderson, R.G.; Ng, G.; Seitz, N.C.; Peterson, T.; McClung, C.R.; McDowell, J.M.; Kong, D.; Kwak, J.M.; et al. Crosstalk between the Circadian Clock and Innate Immunity in Arabidopsis. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003370.

- Yang, M.; Han, X.; Yang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Hu, Y. The Arabidopsis circadian clock protein PRR5 interacts with and stimulates ABI5 to modulate abscisic acid signaling during seed germination. Plant Cell 2021, 33, 3022–3041.

- Lee, H.G.; Mas, P.; Seo, P.J. MYB96 shapes the circadian gating of ABA signaling in Arabidopsis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 17754.

- Webb, A.A.R.; Satake, A. Understanding Circadian Regulation of Carbohydrate Metabolism in Arabidopsis Using Mathematical Models. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015, 56, 586–593.

- Göring, H.; Koshuchowa, S.; Deckert, C. Influence of Gibberellic Acid on Stomatal Movement. Biochem. Physiol. Pflanz. 1990, 186, 367–374.

- Aliniaeifard, S.; van Meeteren, U. Can prolonged exposure to low VPD disturb the ABA signalling in stomatal guard cells? J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 3551–3566.

- Tallman, G. Are diurnal patterns of stomatal movement the result of alternating metabolism of endogenous guard cell ABA and accumulation of ABA delivered to the apoplast around guard cells by transpiration? J. Exp. Bot. 2004, 55, 1963–1976.

- Kushiro, T.; Okamoto, M.; Nakabayashi, K.; Yamagishi, K.; Kitamura, S.; Asami, T.; Hirai, N.; Koshiba, T.; Kamiya, Y.; Nambara, E. The Arabidopsis cytochrome P450 CYP707A encodes ABA 8′-hydroxylases: Key enzymes in ABA catabolism. EMBO J. 2004, 23, 1647–1656.

- Hassidim, M.; Dakhiya, Y.; Turjeman, A.; Hussien, D.; Shor, E.; Anidjar, A.; Goldberg, K.; Green, R.M. CIRCADIAN CLOCK ASSOCIATED1 (CCA1) and the Circadian Control of Stomatal Aperture. Plant Physiol. 2017, 175, 1864–1877.

- Chowdhury, F.I.; Arteaga, C.; Alam, M.S.; Alam, I.; Resco de Dios, V. Drivers of nocturnal stomatal conductance in C3 and C4 plants. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 814, 151952.

- Nakamichi, N.; Takao, S.; Kudo, T.; Kiba, T.; Wang, Y.; Kinoshita, T.; Sakakibara, H. Improvement of Arabidopsis Biomass and Cold, Drought and Salinity Stress Tolerance by Modified Circadian Clock-Associated PSEUDO-RESPONSE REGULATORs. Plant Cell Physiol. 2016, 57, 1085–1097.

- Panchal, S.; Melotto, M. Stomate-based defense and environmental cues. Plant Signal. Behav. 2017, 12, e1362517.

- Shomali, A.; Aliniaeifard, S. Overview of Signal Transduction in Plants under Salt and Drought Stresses. In Salt and Drought Stress Tolerance in Plants; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 231–258.

- Aliniaeifard, S.; Shomali, A.; Seifikalhor, M.; Lastochkina, O. Calcium Signaling in Plants under Drought. In Salt and Drought Stress Tolerance in Plants; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 259–298.

- Zhang, S.; Wu, Q.R.; Liu, L.L.; Zhang, H.M.; Gao, J.W.; Pei, Z.M. Osmotic stress alters circadian cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations and OSCA1 is required in circadian gated stress adaptation. Plant Signal. Behav. 2020, 15, 1836883.

- Somers, D.E.; Webb, A.A.R.; Pearson, M.; Kay, S.A. The short-period mutant, toc1-1, alters circadian clock regulation of multiple outputs throughout development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 1998, 125, 485–494.

- Dodd, A.N.; Parkinson, K.; Webb, A.A.R. Independent circadian regulation of assimilation and stomatal conductance in the ztl-1 mutant of Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2004, 162, 63–70.

- Simon, N.M.L.; Graham, C.A.; Comben, N.E.; Hetherington, A.M.; Dodd, A.N. The circadian clock influences the long-term water use efficiency of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2020, 183, 317–330.

- Graf, A.; Schlereth, A.; Stitt, M.; Smith, A.M. Circadian control of carbohydrate availability for growth in Arabidopsis plants at night. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 9458–9463.

- Resco de Dios, V.; Gessler, A.; Ferrio, J.P.; Alday, J.G.; Bahn, M.; del Castillo, J.; Devidal, S.; García-Muñoz, S.; Kayler, Z.; Landais, D.; et al. Circadian rhythms have significant effects on leaf-to-canopy scale gas exchange under field conditions. Gigascience 2016, 5, 43.

- Chaves, M.M.; Costa, J.M.; Zarrouk, O.; Pinheiro, C.; Lopes, C.M.; Pereira, J.S. Controlling stomatal aperture in semi-arid regions—The dilemma of saving water or being cool? Plant Sci. 2016, 251, 54–64.

- Resco de Dios, V. Circadian regulation and diurnal variation in gas exchange. Plant Physiol. 2017, 175, 3–4.

- Hauser, F.; Waadt, R.; Schroeder, J.I. Evolution of Abscisic Acid Synthesis and Signaling Mechanisms. Curr. Biol. 2011, 21, R346–R355.

- Kimura, Y.; Aoki, S.; Ando, E.; Kitatsuji, A.; Watanabe, A.; Ohnishi, M.; Takahashi, K.; Inoue, S.; Nakamichi, N.; Tamada, Y.; et al. A flowering integrator, SOC1, affects stomatal opening in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015, 56, 640–649.

- Kinoshita, T.; Ono, N.; Hayashi, Y.; Morimoto, S.; Nakamura, S.; Soda, M.; Kato, Y.; Ohnishi, M.; Nakano, T.; Inoue, S.; et al. FLOWERING LOCUS T Regulates Stomatal Opening. Curr. Biol. 2011, 21, 1232–1238.

- Ando, E.; Ohnishi, M.; Wang, Y.; Matsushita, T.; Watanabe, A.; Hayashi, Y.; Fujii, M.; Ma, J.F.; Inoue, S.; Kinoshita, T. TWIN SISTER OF FT, GIGANTEA, and CONSTANS Have a Positive But Indirect Effect on Blue Light-Induced Stomatal Opening in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162, 1529–1538.

- Liu, X.L. ELF3 Encodes a Circadian Clock-Regulated Nuclear Protein That Functions in an Arabidopsis PHYB Signal Transduction Pathway. Plant Cell 2001, 13, 1293–1304.

- Chen, C.; Xiao, Y.-G.; Li, X.; Ni, M. Light-Regulated Stomatal Aperture in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 2012, 5, 566–572.

- Kie bowicz-Matuk, A.; Rey, P.; Rorat, T. Interplay between circadian rhythm, time of the day and osmotic stress constraints in the regulation of the expression of a Solanum Double B-box gene. Ann. Bot. 2014, 113, 831–842.

- Marcolino-Gomes, J.; Rodrigues, F.A.; Fuganti-Pagliarini, R.; Bendix, C.; Nakayama, T.J.; Celaya, B.; Molinari, H.B.C.; de Oliveira, M.C.N.; Harmon, F.G.; Nepomuceno, A. Diurnal oscillations of soybean circadian clock and drought responsive genes. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86402.

- Wilkins, O.; Bräutigam, K.; Campbell, M.M. Time of day shapes Arabidopsis drought transcriptomes. Plant J. 2010, 63, 715–727.

- Li, J.; Liu, Y.-H.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, C.; Yu, X.; Yu, S.-W. Drought stress modulates diurnal oscillations of circadian clock and drought-responsive genes in Oryza sativa L. Yi Chuan = Hereditas 2017, 39, 837–846.

- Mizuno, T.; Yamashino, T. Comparative transcriptome of diurnally oscillating genes and hormone-responsive genes in Arabidopsis thaliana: Insight into circadian clock-controlled daily responses to common ambient stresses in plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008, 49, 481–487.

- Chen, J.; Song, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, D. Genome-Wide Analysis of Gene Expression in Response to Drought Stress in Populus simonii. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2013, 31, 946–962.

- Syed, N.H.; Prince, S.J.; Mutava, R.N.; Patil, G.; Li, S.; Chen, W.; Babu, V.; Joshi, T.; Khan, S.; Nguyen, H.T. Core clock, SUB1, and ABAR genes mediate flooding and drought responses via alternative splicing in soybean. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 7129–7149.

- Valim, H.F.; McGale, E.; Yon, F.; Halitschke, R.; Fragoso, V.; Schuman, M.C.; Baldwin, I.T. The Clock Gene TOC1 in Shoots, Not Roots, Determines Fitness of Nicotiana attenuata under Drought. Plant Physiol. 2019, 181, 305–318.

- Baek, D.; Kim, W.-Y.; Cha, J.-Y.; Park, H.J.; Shin, G.; Park, J.; Lim, C.J.; Chun, H.J.; Li, N.; Kim, D.H.; et al. The GIGANTEA-ENHANCED EM LEVEL Complex Enhances Drought Tolerance via Regulation of Abscisic Acid Synthesis. Plant Physiol. 2020, 184, 443–458.

- Wang, J.; Du, Z.; Huo, X.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Pan, A.; Wang, X.; Wang, F.; Zhang, J. Genome-wide analysis of PRR gene family uncovers their roles in circadian rhythmic changes and response to drought stress in Gossypium hirsutum L. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9936.

- Nakamichi, N.; Kudo, T.; Makita, N.; Kiba, T.; Kinoshita, T.; Sakakibara, H. Flowering time control in rice by introducing Arabidopsis clock-associated PSEUDO-RESPONSE REGULATOR 5. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2020, 84, 970–979.

- Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Gene networks involved in drought stress response and tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 221–227.

- Sanchez, A.; Shin, J.; Davis, S.J. Abiotic stress and the plant circadian clock. Plant Signal. Behav. 2011, 6, 223–231.

- Matsui, A.; Ishida, J.; Morosawa, T.; Mochizuki, Y.; Kaminuma, E.; Endo, T.A.; Okamoto, M.; Nambara, E.; Nakajima, M.; Kawashima, M.; et al. Arabidopsis transcriptome analysis under drought, cold, high-salinity and ABA treatment conditions using a tiling array. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008, 49, 1135–1149.

- Robertson, F.C.; Skeffington, A.W.; Gardner, M.J.; Webb, A.A.R. Interactions between circadian and hormonal signalling in plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 2009, 69, 419–427.