A firm’s corporate social responsibility (CSR) approach can encompass a wide variety of activities. These may include philanthropy (donating to charities), volunteering by employees, ethical labor practices, and implementing environmentally friendly operations. Diverse stakeholders and nationalities may view certain social initiatives as less or more important than others. As a result, firms respond by prioritizing those CSR activities that stakeholders in their operating environment consider important. This leads to firms having CSR preferences for some social and environmental activities over others. Traditionally, CSR in South Africa was delivered through corporate social investment (CSI): a philanthropic effort with firms implementing their social responsibility through charitable donations targeted at the education and healthcare of a firm’s surrounding communities.

1. Introduction

A firm’s corporate social responsibility (CSR) approach can encompass a wide variety of activities. These may include philanthropy (donating to charities), volunteering by employees, ethical labor practices, and implementing environmentally friendly operations

[1]. Firms do not implement the entire range of CSR activities. To guide their choice of activities, firms look to the desires and requirements of different stakeholders and institutions in their respective countries of operation. Diverse stakeholders and nationalities may view certain social initiatives as less or more important than others

[2][3]. As a result, firms respond by prioritizing those CSR activities that stakeholders in their operating environment consider important. This leads to firms having CSR preferences for some social and environmental activities over others.

One observes, for example, that while firms from Europe may prioritize climate change

[4], firms from the Middle East and Africa regions pay attention to the social issues facing the surrounding communities

[3]. While some regions allow for voluntary activities, others prescribe certain CSR activities. Firms in state-led market economies, such as France, are faced with regulated versions of CSR. In contrast, firms from liberal market economies, such as the U.S.A., are free to select CSR activities

[5][6][7].

CSR preferences may also align with subnational influences of industry norms and regulations

[8][9]. For example, the food industry prioritizes consumers willing to pay for environmentally friendly products when firms select CSR activities related to environmental responsibility

[10]. Influential stakeholders, such as large customers, may also drive preferences

[11][12][13].

As South Africa is a country of the Global South, burdened with socio-economic problems, researchers have yet to learn whether firms from South Africa possess different CSR preferences to firms of the other countries explored by researchers to date. Overall, the overarching driver of CSR preferences is a mix of institutional pressures often activated through stakeholders

[14]. In South Africa, with BEE policy featuring an important institutional driver and a state-driven variant of CSR, it will be interesting to explore whether the topmost CSR activities also feature in the BEE codes of practice. Additionally, to capture any heterogeneity in management responses, researchers believe stakeholder pressures across industries become salient. Mining firms, for example, are located next door to local communities that serve as essential stakeholders, while service companies tend to be in cities full of middle-class consumers. With various CSR preferences across nations, this entry explores what leads firms in South Africa to select specific CSR initiatives over others.

2. CSR in South Africa

Earlier, Bowen

[15] referred to CSR as the obligation of managers to act in the interest of society. Davis

[16] suggested that these actions must be beyond the firm’s direct economic interest. The components of CSR, proposed by Carroll

[17], include legal, ethical, discretionary, philanthropic, and economic aspects. Notably, the economic component includes the principle of fairness, where businesses are obliged to sell their goods and services at a fair price to make a profit.

As various difficulties experienced by society have arisen, public expectations of corporate responsibility have also evolved. From the original focus on social issues, CSR scholars now argue that social issues include the “stewardship of the natural environment” where environmental issues are viewed “as trespasses against society” (

[18] p. 107). This has led to viewing corporate performance as a triple bottom line: economic, social and environmental

[19]. A helpful guide to the key performance indicators of each dimension of CSR can be found in the Directive 2014/95/EU

[20].

As a result of the rigorous discussion about implementing corporate responsibility in Europe, CSR has been revised from its voluntary posture, originating in the U.S., to a hybrid of voluntary and regulated elements

[7][19] For example, in Europe, it has been proposed that “public authorities should play a supporting role through a smart mix of voluntary policy measures and, where necessary, complementary regulation” (

[21] p. 7). It has been argued that the spirit of regulatory measures is not to reduce the discretion afforded to firms; instead, they should guide firms

[22].

The South African environment presents private firms with abundant opportunities to help to address social ills. South Africa has the highest level of inequality globally, with a Gini index of 63

[23] and about a third of its population lives in poverty

[24]. A significant reason for this inequality is the stubborn unemployment rate, now at 35%

[25]. Many of the unemployed are less educated and unskilled, and the demand for them arising from, for example, primary industries, such as agriculture and mining, has continued to decline. Structural changes in the economy have demanded more skilled labor. South Africa has been described as a land of “two nations”

[26]: a rich, formal economy and a poor, informal economy. With low national skill and education levels, high crime rates, and poor access to clean drinking water and housing, the provision of social services, traditionally supported by charities and the government, is under severe strain

[27]. In this case, the private sector’s social responsibility efforts, using private resources that can be used efficiently and effectively, become valuable to compensate for the inadequate social services delivered by the government.

Traditionally, CSR in South Africa was delivered through corporate social investment (CSI): a philanthropic effort with firms implementing their social responsibility through charitable donations targeted at the education and healthcare of a firm’s surrounding communities

[28][29]. Education efforts, for example, included providing monies towards schooling infrastructure, teacher training, and equipment. Firms’ move to broader versions of CSR can be traced to their international activity and subject to corporate governance rules in London, for example, and the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) abroad; the local King Code of corporate governance and formation of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange’s (JSE) socially responsible investment (SRI) index; and state legislation in terms of Mines Health and Safety Act of 1996 and Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) policy

[23].

BEE has since become a “prominent local variant of the global CSR movement” (

[29] p. 573). However, the BEE Codes of Good Practice “focus on one area of CSR, namely, social issues directed at direct and indirect empowerment of Black people” (

[30] p. 677). Specifically, the Codes recognize the firm’s efforts towards introducing Black owners, executives, and other employees and managers, and the skills development of both internal and external beneficiaries (see

Table 1). For example, external beneficiaries may be targeted for internships and bursaries, contributing to the nation’s attempts to increase its tertiary educated population. The Codes also encourage firms to develop new Black-owned enterprises and existing suppliers across the supply chain. This involves support through procurement as well as funding. Lastly, the Codes encourage firms to contribute at least one percent of net profit after tax to the nation’s socio-economic development initiatives. This might take the form of grants and pro bono services towards the development of local communities. Many of the CSI efforts of firms in the past fall within this socio-economic development element of the Codes, reflecting the breadth of the post-apartheid state’s CSR requirements compared to historical CSI efforts.

Table 1. BEE Codes of South Africa.

| Element |

Weighting |

| Black ownership |

25 |

| Management |

15 |

| Skills development |

20 |

| Enterprise and supplier development |

40 |

| Socio economic development |

5 |

Notably, BEE policy has been designed to be implemented via state procurement and licensing. The SA state has legislated BEE in the government sector allowing state departments and state-owned enterprises to procure goods and services from the market based on two criteria: price and BEE. The state will also view the BEE status of license applicants in certain industries, e.g., a license for mining rights and a license to provide telecommunication services. Notably, when business is conducted between two private-sector firms, BEE compliance remains voluntary. In practice, firms that wish to conduct business with the state must also demonstrate that they procure goods and services from suppliers that comply with BEE regulations. In this way, BEE policy affects the entire supply chain of firms that conduct business with the state

[31][32].

Except for Black ownership and management control, the general upliftment of Black people through human resource and skills development and socio-economic development, as a version of social responsibility, has been uncontested

[33]. However, ownership and management control may be considered as “special measures” accommodated in international human rights law

[34]. In addition, Black ownership has a recursive relationship with efforts to promote procurement and enterprise development type equity (compared to employment equity). These efforts rely on the state and established private firms locating Black-owned enterprises across all sectors of the South African economy. Additionally, currently, they remain scarcely represented in the South African economy.

The King Codes of Governance for South Africa is another influential regulation. Firms are required to report their CSR performance and make those CSR disclosures to be independently assured

[35]. Although these reports do not oblige firms to engage in CSR projects, the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) has, since 2010, mandated integrated reporting and requires all listed firms to comply with its principles

[36]. Firms that are part of the FTSE/JSE All Share Index are invited to participate in the annual assessment. Performance criteria are aligned with the “environmental, social and economic pillars of the triple bottom line” (

[37] p. 246). As a result of all these initiatives, sustainability reporting is now commonplace in South Africa with the publication of spheres of the triple bottom line in corporate economic performance reports

[38].

Researchers' approach to CSR emanates from the debate about the suitability of the Global North approach to social responsibility indices (SRI) for the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) (see, for example, Heese

[39]). Eventually, the JSE developed its version of a SRI by borrowing from, among others, the FTSE4Good Index, the GRI, King Codes of Good Governance, and the Sullivan Principles

[39][40][41]. Though the Index includes metrics connected to the natural environment, South African organizations have prioritized the socio-economic aspects of international standards. These include training and development, employee and community relations, equal opportunities, health and safety, stakeholder engagement, BEE, and HIV/Aids

[39][41].

With the efforts of South African organizations at CSR thus far, South Africa is the top performer on the African continent with an overall CSR index of 55 out of 100

[42]. By comparison, the top-performing country in Europe, Latvia, has 64. South Africa was also ranked at 106 of the 165 countries rated on the 17 sustainable development goals

[43].

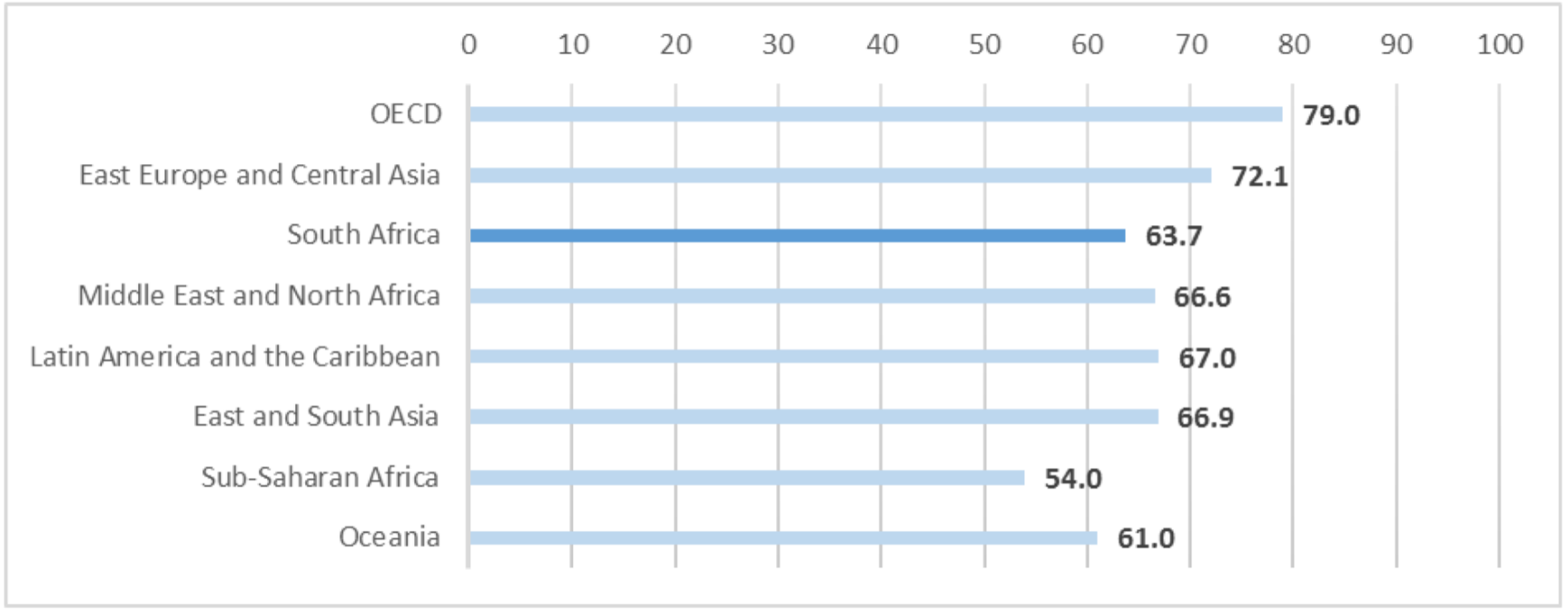

Figure 1 below shows that South Africa has an SDG Index score of 63.7 out of 100 based on all 17 SDGs. The low SDG Index scores in low-income countries have been attributed to putting less effort on environmental aspects, ending extreme poverty, and providing access to essential services and infrastructure.

Figure 1. Sustainable Development Goals Index Scores.