| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Niels Grote Beverborg | -- | 4895 | 2022-04-11 10:54:26 | | | |

| 2 | Vicky Zhou | + 2 word(s) | 4897 | 2022-04-11 11:37:31 | | | | |

| 3 | Vicky Zhou | -35 word(s) | 4862 | 2022-04-11 11:53:26 | | |

Video Upload Options

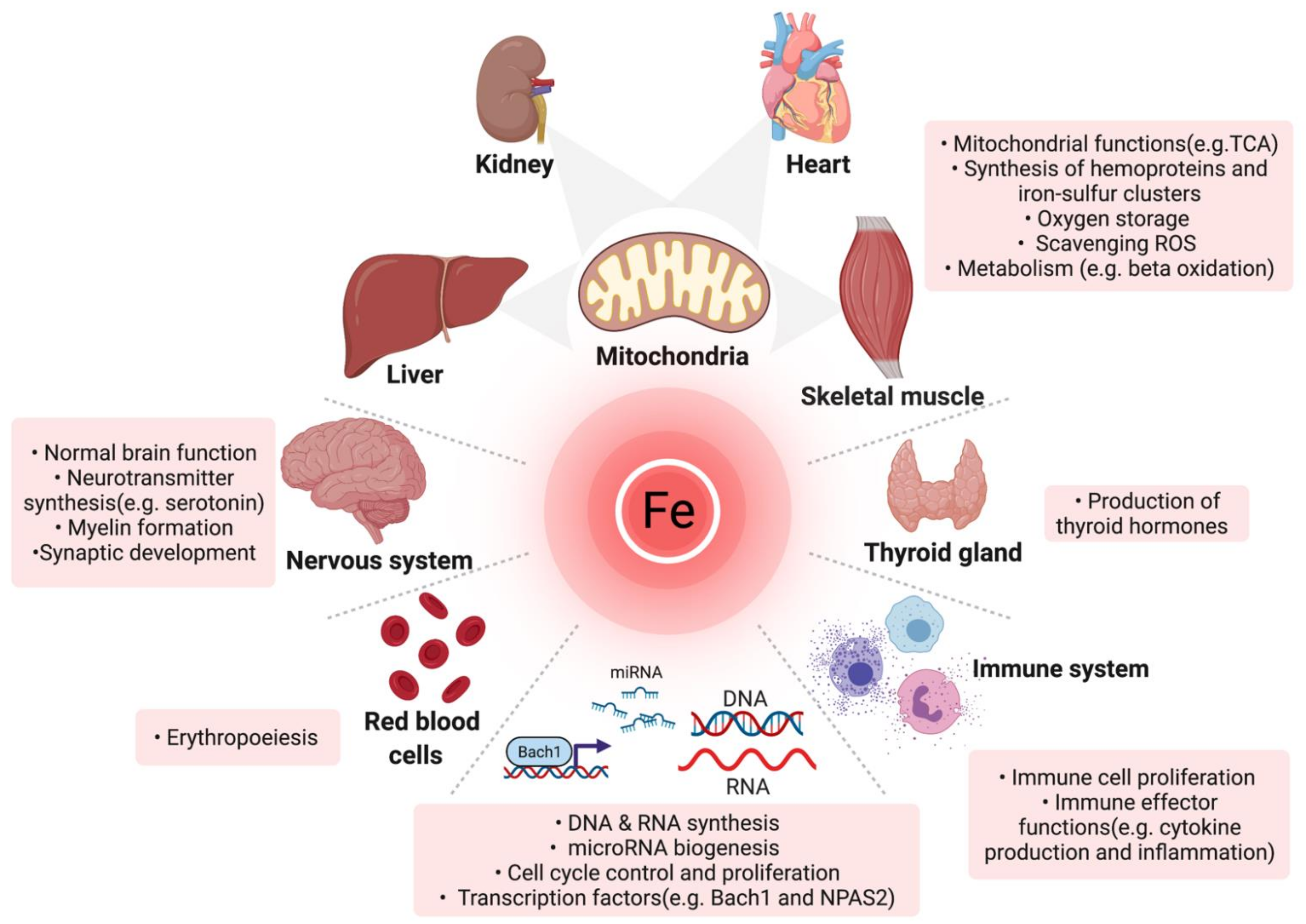

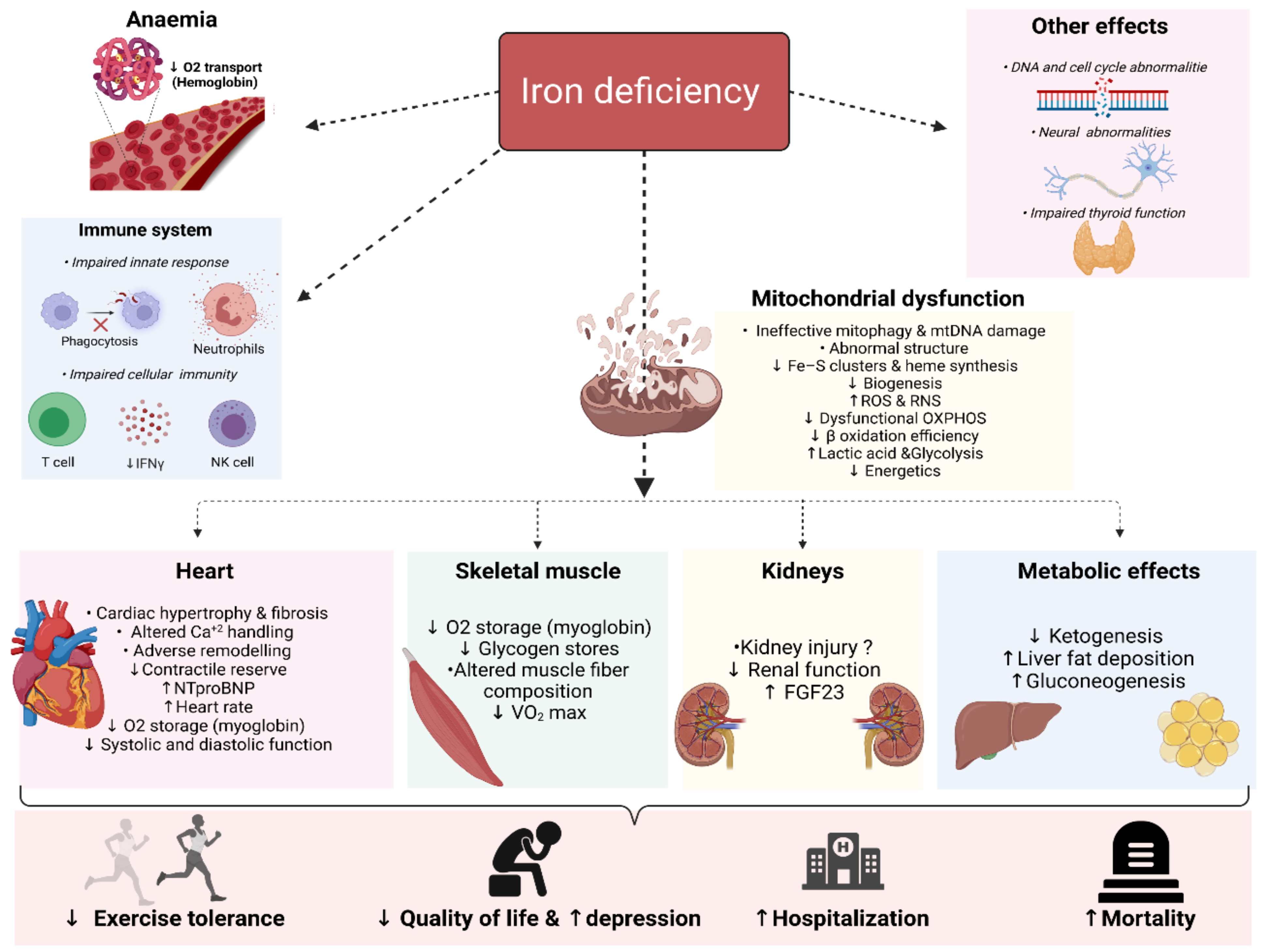

Iron is an essential micronutrient for a myriad of physiological processes in the body beyond erythropoiesis. Iron deficiency (ID) is a common comorbidity in patients with heart failure (HF), with a prevalence reaching up to 59% even in non-anaemic patients. ID impairs exercise capacity, reduces the quality of life, increases hospitalisation rate and mortality risk regardless of anaemia. Intravenously correcting ID has emerged as a promising treatment in HF as it has been shown to alleviate symptoms, improve quality of life and exercise capacity and reduce hospitalisations. However, the pathophysiology of ID in HF remains poorly characterised. Recognition of ID in HF triggered more research with the aim to explain how correcting ID improves HF status as well as the underlying causes of ID in the first place. In the past few years, significant progress has been made in understanding iron homeostasis by characterising the role of the iron-regulating hormone hepcidin, the effects of ID on skeletal and cardiac myocytes, kidneys and the immune system.

1. Introduction

1.1. Physiologic Roles and Regulation of Iron

| Function | Protein |

|---|---|

| Oxygen transport | Hemoglobin |

| Oxygen storage | Myoglobin |

| Lipid and cholesterol biosynthesis | NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase, fatty acid desaturases, cytochrome P-450 subfamily 51 and Cytochrome P450 Family 7 Subfamily A Member 1 |

| Oxygen sensing and regulation of hypoxia | Hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylases |

| Synthesis catecholamines and neurotransmitters | Tryptophan hydroxylase, tyrosine hydroxylase, monoamine oxidase and aldehyde oxidase |

| Host defence, inflammation and production of nitric oxide | Myeloperoxidase, NADPH oxidase, indoleamine 2,3- dioxygenase, nitric oxide synthase and lipoxygenases |

| DNA synthesis, replication and repair | Ribonucleotide reductases, DNA polymerases, DNA glycolsylases, DNA primases, DNA helicasess and DNA endonucleases. Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenas |

| Collagen synthesis | Proline hydroxylase |

| Electron transport and respiratory chain | Cytochrome C oxidase, Cytochrome b, cytochrome c1, Cytochrome oxidase P540, NADH dehydrogenase, aconitase, citrate synthase, Succinyl dehydogease, cytochrome reductase, Complex I-III, rieske protein, NADH ferrocyanide oxidoreductase |

| Adrenoxin | Steroid hydoxylation |

| Antioxidant defence | Catalase |

| Response to oxidative stress | Glutathione peroxidase 2, lactoperoxidase |

| Amino acid metabolism | Tryptophan pyrrolase, Phenaylalanine hydroxylase, deoxyhypusine hydroxylase |

| Carnitine biosynthesis | α-ketoglutarate (αKG)-dependent oxygenases |

| Synthesis of thyroid hormone | Thyroid peroxidase |

| Drug detoxification | Cytochrome P450 , NADPH cytochrome P450 reductase |

| Prostaglandin thromboxane synthesis, inflammation and response to oxidative stress | Cyclooxyenase |

| microRNA biogenesis | DiGeorge Syndrome Critical Region Gene 8 |

| Ribosome function and tRNA modification | ABCE1, CDKRAP1, TYW1 and CDKAL1, Methylthiotransferase |

| Haeme biosynthesis | Ferrochelatase |

| Apoptosis and oxygen transport in the brain | Neuroglobin |

| Purine metabolism and synthesis | Xanthine oxidase, amidophosphoribosyltransferase |

1.2. Definition of Iron Deficiency

2. Deleterious Biological Consequences of Iron Deficiency

2.1. Mitochondrial Function and Metabolic Effects

2.2. Heart

2.3. Skeletal Muscles

2.4. Kidneys

2.5. The Immune System

2.6. The Brain

2.7. Thyroid Gland

3. Novel Therapeutic Options for Targeting Iron Metabolism

4. Conclusions

References

- Muckenthaler, M.U.; Rivella, S.; Hentze, M.W.; Galy, B. A Red Carpet for Iron Metabolism. Cell 2017, 168, 344–361.

- Andrews, N.C.; Schmidt, P.J. Iron homeostasis. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2007, 69, 69–85.

- Cairo, G.; Bernuzzi, F.; Recalcati, S. A precious metal: Iron, an essential nutrient for all cells. Genes Nutr. 2006, 1, 25–39.

- Ponka, P.; Schulman, H.M.; Woodworth, R.C.; Richter, G.W. Iron Transport and Storage; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2000.

- Pasricha, S.R.; Tye-Din, J.; Muckenthaler, M.U.; Swinkels, D.W. Iron deficiency. Lancet 2021, 397, 233–248.

- Partin, A.C.; Ngo, T.D.; Herrell, E.; Jeong, B.C.; Hon, G.; Nam, Y. Heme enables proper positioning of Drosha and DGCR8 on primary microRNAs. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1737.

- Zhang, C. Essential functions of iron-requiring proteins in DNA replication, repair and cell cycle control. Protein Cell 2014, 5, 750–760.

- Ponikowski, P.; Kirwan, B.A.; Anker, S.D.; Dorobantu, M.; Drozdz, J.; Fabien, V.; Filippatos, G.; Haboubi, T.; Keren, A.; Khintibidze, I.; et al. Rationale and design of the AFFIRM-AHF trial: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial comparing the effect of intravenous ferric carboxymaltose on hospitalisations and mortality in iron-deficient patients admitted for acute heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 1651–1658.

- Jankowska, E.A.; Von Haehling, S.; Anker, S.D.; MacDougall, I.C.; Ponikowski, P. Iron deficiency and heart failure: Diagnostic dilemmas and therapeutic perspectives. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 816–829.

- Beard, J.L. Iron biology in immune function, muscle metabolism and neuronal functioning. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 568S–580S.

- Zohora, F.; Bidad, K.; Pourpak, Z.; Moin, M. Biological and Immunological Aspects of Iron Deficiency Anemia in Cancer Development: A Narrative Review. Nutr. Cancer 2018, 70, 546–556.

- Hentze, M.W.; Muckenthaler, M.U.; Galy, B.; Camaschella, C. Two to Tango: Regulation of Mammalian Iron Metabolism. Cell 2010, 142, 24–38.

- Silva, B.; Faustino, P. An overview of molecular basis of iron metabolism regulation and the associated pathologies. Biochim. Biophys. Acta—Mol. Basis Dis. 2015, 1852, 1347–1359.

- Ganz, T. Systemic iron homeostasis. Physiol. Rev. 2013, 93, 1721–1741.

- Lawen, A.; Lane, D.J.R. Mammalian iron homeostasis in health and disease: Uptake, storage, transport, and molecular mechanisms of action. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2013, 18, 2473–2507.

- Cleland, J.G.F.; Zhang, J.; Pellicori, P.; Dicken, B.; Dierckx, R.; Shoaib, A.; Wong, K.; Rigby, A.; Goode, K.; Clark, A.L. Prevalence and outcomes of anemia and hematinic deficiencies in patients with chronic heart failure. JAMA Cardiol. 2016, 1, 539–547.

- Graham, F.J.; Masini, G.; Pellicori, P.; Cleland, J.G.F.; Greenlaw, N.; Friday, J.; Kazmi, S.; Clark, A.L. Natural history and prognostic significance of iron deficiency and anaemia in ambulatory patients with chronic heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2021.

- Jankowska, E.A.; Kasztura, M.; Sokolski, M.; Bronisz, M.; Nawrocka, S.; Oleśkowska-Florek, W.; Zymliński, R.; Biegus, J.; Siwołowski, P.; Banasiak, W.; et al. Iron deficiency defined as depleted iron stores accompanied by unmet cellular iron requirements identifies patients at the highest risk of death after an episode of acute heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 2468–2476.

- Van der Wal, H.H.; Grote Beverborg, N.; Dickstein, K.; Anker, S.D.; Lang, C.C.; Ng, L.L.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Voors, A.A.; van der Meer, P. Iron deficiency in worsening heart failure is associated with reduced estimated protein intake, fluid retention, inflammation, and antiplatelet use. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 3616–3625.

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726.

- Martens, P.; Grote Beverborg, N.; van der Meer, P. Iron deficiency in heart failure—Time to redefine. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2020, zwaa119.

- Ueda, T.; Kawakami, R.; Nogi, K.; Nogi, M.; Ishihara, S.; Nakada, Y.; Nakano, T.; Hashimoto, Y.; Nakagawa, H.; Nishida, T.; et al. Serum iron: A new predictor of adverse outcomes independently from serum hemoglobin levels in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2395.

- Beverborg, N.G.; Klip, I.T.; Meijers, W.C.; Voors, A.A.; Vegter, E.L.; Van Der Wal, H.H.; Swinkels, D.W.; Van Pelt, J.; Mulder, A.B.; Bulstra, S.K.; et al. Definition of iron deficiency based on the gold standard of bone marrow iron staining in heart failure patients. Circ. Heart Fail. 2018, 11, e004519.

- Sierpinski, R.; Josiak, K.; Suchocki, T.; Wojtas-Polc, K.; Mazur, G.; Butrym, A.; Rozentryt, P.; Meer, P.; Comin-Colet, J.; Haehling, S.; et al. High soluble transferrin receptor in patients with heart failure: A measure of iron deficiency and a strong predictor of mortality. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2021, 23, 919–932.

- Anker, S.D.; Comin Colet, J.; Filippatos, G.; Willenheimer, R.; Dickstein, K.; Drexler, H.; Lüscher, T.F.; Bart, B.; Banasiak, W.; Niegowska, J.; et al. Ferric Carboxymaltose in Patients with Heart Failure and Iron Deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 2436–2448.

- Mei, Z.; Cogswell, M.E.; Parvanta, I.; Lynch, S.; Beard, J.L.; Stoltzfus, R.J.; Grummer-Strawn, L.M. Hemoglobin and ferritin are currently the most efficient indicators of population response to iron interventions: An analysis of nine randomized controlled trials. J. Nutr. 2005, 135, 1974–1980.

- Dignass, A.; Farrag, K.; Stein, J. Limitations of Serum Ferritin in Diagnosing Iron Deficiency in Inflammatory Conditions. Int. J. Chronic Dis. 2018, 2018, 9394060.

- Palau, P.; Llàcer, P.; Domínguez, E.; Tormo, J.P.; Zakarne, R.; Mollar, A.; Martínez, A.; Miñana, G.; Santas, E.; Almenar, L.; et al. Iron deficiency and short-term adverse events in patients with decompensated heart failure. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2021, 110, 1292–1298.

- Gentil, J.R.d.S.; Fabricio, C.G.; Tanaka, D.M.; Suen, V.M.M.; Volpe, G.J.; Marchini, J.S.; Simões, M.V. Should we use ferritin in the diagnostic criteria of iron deficiency in heart failure patients? Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2020, 39, 119–123.

- Moliner, P.; Jankowska, E.A.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Farre, N.; Rozentryt, P.; Enjuanes, C.; Polonski, L.; Meroño, O.; Voors, A.A.; Ponikowski, P.; et al. Clinical correlates and prognostic impact of impaired iron storage versus impaired iron transport in an international cohort of 1821 patients with chronic heart failure. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 243, 360–366.

- Anker, S.D.; Kirwan, B.-A.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Filippatos, G.; Comin-Colet, J.; Ruschitzka, F.; Lüscher, T.F.; Arutyunov, G.P.; Motro, M.; Mori, C.; et al. Effects of ferric carboxymaltose on hospitalisations and mortality rates in iron-deficient heart failure patients: An individual patient data meta-analysis. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2018, 20, 125–133.

- Martens, P.; Dupont, M.; Dauw, J.; Nijst, P.; Herbots, L.; Dendale, P.; Vandervoort, P.; Bruckers, L.; Tang, W.H.W.; Mullens, W. The effect of intravenous ferric carboxymaltose on cardiac reverse remodelling following cardiac resynchronization therapy—the IRON-CRT trial. Eur. Heart J. 2021, ehab411.

- Ponikowski, P.; Kirwan, B.-A.; Anker, S.D.; McDonagh, T.; Dorobantu, M.; Drozdz, J.; Fabien, V.; Filippatos, G.; Göhring, U.M.; Keren, A.; et al. Ferric carboxymaltose for iron deficiency at discharge after acute heart failure: A multicentre, double-blind, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 2020, 396, 1895–1904.

- Cao, G.Y.; Li, Y.; Jin, P.F.; Hu, X. Circadian rhythm in serum iron levels. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2012, 147, 63–66.

- Tomasz, G.; Ewa, W.; Jolanta, M. Biomarkers of iron metabolism in chronic kidney disease. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2021, 53, 935–944.

- Yu, P.H.; Lin, M.Y.; Chiu, Y.W.; Lee, J.J.; Hwang, S.J.; Hung, C.C.; Chen, H.C. Low serum iron is associated with anemia in CKD stage 1–4 patients with normal transferrin saturations. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8343.

- Pfeiffer, C.M.; Looker, A.C. Laboratory methodologies for indicators of iron status: Strengths, limitations, and analytical challenges. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 106, 1606S–1614S.

- Manckoundia, P.; Konaté, A.; Hacquin, A.; Nuss, V.; Mihai, A.M.; Vovelle, J.; Dipanda, M.; Putot, S.; Barben, J.; Putot, A. Iron in the general population and specificities in older adults: Metabolism, causes and consequences of decrease or overload, and biological assessment. Clin. Interv. Aging 2020, 15, 1927–1938.

- Leszek, P.; Sochanowicz, B.; Szperl, M.; Kolsut, P.; Brzóska, K.; Piotrowski, W.; Rywik, T.M.; Danko, B.; Polkowska-Motrenko, H.; Rózański, J.M.; et al. Myocardial iron homeostasis in advanced chronic heart failure patients. Int. J. Cardiol. 2012, 159, 47–52.

- Wolf, M.; Rubin, J.; Achebe, M.; Econs, M.J.; Peacock, M.; Imel, E.A.; Thomsen, L.L.; Carpenter, T.O.; Weber, T.; Brandenburg, V.; et al. Effects of Iron Isomaltoside vs Ferric Carboxymaltose on Hypophosphatemia in Iron-Deficiency Anemia: Two Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA 2020, 323, 432–443.

- Hirsch, V.G.; Tongers, J.; Bode, J.; Berliner, D.; Widder, J.D.; Escher, F.; Mutsenko, V.; Chung, B.; Rostami, F.; Guba-Quint, A.; et al. Cardiac iron concentration in relation to systemic iron status and disease severity in non-ischaemic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2020, 22, 2038–2046.

- Klip, I.T.; Comin-Colet, J.; Voors, A.A.; Ponikowski, P.; Enjuanes, C.; Banasiak, W.; Lok, D.J.; Rosentryt, P.; Torrens, A.; Polonski, L.; et al. Iron deficiency in chronic heart failure: An international pooled analysis. Am. Heart J. 2013, 165.

- Okonko, D.O.; Mandal, A.K.J.; Missouris, C.G.; Poole-Wilson, P.A. Disordered iron homeostasis in chronic heart failure: Prevalence, predictors, and relation to anemia, exercise capacity, and survival. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 58, 1241–1251.

- Jankowska, E.A.; Rozentryt, P.; Witkowska, A.; Nowak, J.; Hartmann, O.; Ponikowska, B.; Borodulin-Nadzieja, L.; Von Haehling, S.; Doehner, W.; Banasiak, W.; et al. Iron deficiency predicts impaired exercise capacity in patients with systolic chronic heart failure. J. Card. Fail. 2011, 17, 899–906.

- Van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Ponikowski, P.; Van Der Meer, P.; Metra, M.; Böhm, M.; Doletsky, A.; Voors, A.A.; MacDougall, I.C.; Anker, S.D.; Roubert, B.; et al. Effect of Ferric Carboxymaltose on Exercise Capacity in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure and Iron Deficiency. Circulation 2017, 136, 1374–1383.

- Paul, B.T.; Manz, D.H.; Torti, F.M.; Torti, S.V. Mitochondria and Iron: Current questions. Expert Rev. Hematol. 2017, 10, 65–79.

- Sheeran, F.L.; Pepe, S. Mitochondrial bioenergetics and dysfunction in failing heart. In Mitochondrial Dynamics in Cardiovascular Medicine; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 982, pp. 65–80.

- Rensvold, J.W.; Ong, S.E.; Jeevananthan, A.; Carr, S.A.; Mootha, V.K.; Pagliarini, D.J. Complementary RNA and protein profiling identifies iron as a key regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis. Cell Rep. 2013, 3, 237–245.

- Baughman, J.M.; Perocchi, F.; Girgis, H.S.; Plovanich, M.; Belcher-Timme, C.A.; Sancak, Y.; Bao, X.R.; Strittmatter, L.; Goldberger, O.; Bogorad, R.L.; et al. Integrative genomics identifies MCU as an essential component of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature 2011, 476, 341–345.

- Walter, P.B.; Knutson, M.D.; Paler-Martinez, A.; Lee, S.; Xu, Y.; Viteri, F.E.; Ames, B.N. Iron deficiency and iron excess damage mitochondria and mitochondrial DNA in rats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 2264–2269.

- Hoes, M.F.; Grote Beverborg, N.; Kijlstra, J.D.; Kuipers, J.; Swinkels, D.W.; Giepmans, B.N.G.; Rodenburg, R.J.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; de Boer, R.A.; van der Meer, P. Iron deficiency impairs contractility of human cardiomyocytes through decreased mitochondrial function. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2018, 20, 910–919.

- Kitamura, N.; Yokoyama, Y.; Taoka, H.; Nagano, U.; Hosoda, S.; Taworntawat, T.; Nakamura, A.; Ogawa, Y.; Tsubota, K.; Watanabe, M. Iron supplementation regulates the progression of high fat diet induced obesity and hepatic steatosis via mitochondrial signaling pathways. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10753.

- Finch, C.A.; Gollnick, P.D.; Hlastala, M.P.; Miller, L.R.; Dillmann, E.; Mackler, B. Lactic acidosis as a result of iron deficiency. J. Clin. Invest. 1979, 64, 129–137.

- Chung, Y.J.; Swietach, P.; Curtis, M.K.; Ball, V.; Robbins, P.A.; Lakhal-Littleton, S. Iron-Deficiency Anemia Results in Transcriptional and Metabolic Remodeling in the Heart Toward a Glycolytic Phenotype. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 7, 361.

- Biegus, J.; Zymliński, R.; Sokolski, M.; Jankowska, E.A.; Banasiak, W.; Ponikowski, P. Elevated lactate in acute heart failure patients with intracellular iron deficiency as an identifier of poor outcome. Kardiol. Pol. 2019, 77, 347–354.

- Xu, W.; Barrientos, T.; Mao, L.; Rockman, H.A.; Sauve, A.A.; Andrews, N.C. Lethal Cardiomyopathy in Mice Lacking Transferrin Receptor in the Heart. Cell Rep. 2015, 13, 533–545.

- Dong, F.; Zhang, X.; Culver, B.; Chew, H.G.; Kelley, R.O.; Ren, J. Dietary iron deficiency induces ventricular dilation, mitochondrial ultrastructural aberrations and cytochrome c release: Involvement of nitric oxide synthase and protein tyrosine nitration. Clin. Sci. 2005, 109, 277–286.

- Toblli, J.E.; Cao, G.; Rivas, C.; Kulaksiz, H. Heart and iron deficiency anaemia in rats with renal insufficiency: The role of hepcidin. Nephrology 2008, 13, 636–645.

- Dziegala, M.; Kasztura, M.; Kobak, K.; Bania, J.; Banasiak, W.; Ponikowski, P.; Jankowska, E.A. Influence of the availability of iron during hypoxia on the genes associated with apoptotic activity and local iron metabolism in rat H9C2 cardiomyocytes and L6G8C5 skeletal myocytes. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 14, 3969–3977.

- Kasztura, M.; Dziegała, M.; Kobak, K.; Bania, J.; Mazur, G.; Banasiak, W.; Ponikowski, P.; Jankowska, E.A. Both iron excess and iron depletion impair viability of rat H9C2 cardiomyocytes and L6G8C5 myocytes. Kardiol. Pol. 2017, 75, 267–275.

- Dziegala, M.; Kobak, K.; Kasztura, M.; Bania, J.; Josiak, K.; Banasiak, W.; Ponikowski, P.; Jankowska, E. Iron Depletion Affects Genes Encoding Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain and Genes of Non Oxidative Metabolism, Pyruvate Kinase and Lactate Dehydrogenase, in Primary Human Cardiac Myocytes Cultured upon Mechanical Stretch. Cells 2018, 7, 175.

- Kamei, A.; Watanabe, Y.; Ishijima, T.; Uehara, M.; Arai, S.; Kato, H.; Nakai, Y.; Abe, K. Dietary iron-deficient anemia induces a variety of metabolic changes and even apoptosis in rat liver: A DNA microarray study. Physiol. Genomics 2010, 42, 149–156.

- Narula, J.; Kolodgie, F.D.; Virmani, R. Apoptosis and cardiomyopathy. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2000, 15, 183–188.

- Brown, D.A.; Perry, J.B.; Allen, M.E.; Sabbah, H.N.; Stauffer, B.L.; Shaikh, S.R.; Cleland, J.G.F.; Colucci, W.S.; Butler, J.; Voors, A.A.; et al. Expert consensus document: Mitochondrial function as a therapeutic target in heart failure. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2017, 14, 238–250.

- Kaludercic, N.; Giorgio, V. The dual function of reactive oxygen/nitrogen species in bioenergetics and cell death: The role of ATP synthase. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 3869610.

- Koskenkorva-Frank, T.S.; Weiss, G.; Koppenol, W.H.; Burckhardt, S. The complex interplay of iron metabolism, reactive oxygen species, and reactive nitrogen species: Insights into the potential of various iron therapies to induce oxidative and nitrosative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 65, 1174–1194.

- Inoue, H.; Hanawa, N.; Katsumata, S.I.; Katsumata-Tsuboi, R.; Takahashi, N.; Uehara, M. Iron deficiency induces autophagy and activates Nrf2 signal through modulating p62/SQSTM. Biomed. Res. 2017, 38, 343–350.

- Melenovsky, V.; Petrak, J.; Mracek, T.; Benes, J.; Borlaug, B.A.; Nuskova, H.; Pluhacek, T.; Spatenka, J.; Kovalcikova, J.; Drahota, Z.; et al. Myocardial iron content and mitochondrial function in human heart failure: A direct tissue analysis. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2016, 19, 522–530.

- Tsutsui, H.; Kinugawa, S.; Matsushima, S. Mitochondrial oxidative stress and dysfunction in myocardial remodelling. Cardiovasc. Res. 2009, 81, 449–456.

- Toblli, J.E.; Cao, G.; Rivas, C.; Giani, J.F.; Dominici, F.P. Intravenous iron sucrose reverses anemia-induced cardiac remodeling, prevents myocardial fibrosis, and improves cardiac function by attenuating oxidative/nitrosative stress and inflammation. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 212, 84–91.

- Paterek, A.; Kępska, M.; Sochanowicz, B.; Chajduk, E.; Kołodziejczyk, J.; Polkowska-Motrenko, H.; Kruszewski, M.; Leszek, P.; Mackiewicz, U.; Mączewski, M. Beneficial effects of intravenous iron therapy in a rat model of heart failure with preserved systemic iron status but depleted intracellular cardiac stores. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15758.

- Inserte, J.; Barrabés, J.A.; Aluja, D.; Otaegui, I.; Bañeras, J.; Castellote, L.; Sánchez, A.; Rodríguez-Palomares, J.F.; Pineda, V.; Miró-Casas, E.; et al. Implications of Iron Deficiency in STEMI Patients and in a Murine Model of Myocardial Infarction. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2021, 6, 567–580.

- Knutson, M.D.; Walter, P.B.; Ames, B.N.; Viteri, F.E. Both iron deficiency and daily iron supplements increase lipid peroxidation in rats. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 621–628.

- Bhandari, S. Impact of intravenous iron on cardiac and skeletal oxidative stress and cardiac mitochondrial function in experimental uraemia chronic kidney disease. Front. Biosci.—Landmark 2021, 26, 442–464.

- Wong, A.-P.; Niedzwiecki, A.; Rath, M. Myocardial energetics and the role of micronutrients in heart failure: A critical review. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2016, 6, 81–92.

- Rineau, E.; Gaillard, T.; Gueguen, N.; Procaccio, V.; Henrion, D.; Prunier, F.; Lasocki, S. Iron deficiency without anemia is responsible for decreased left ventricular function and reduced mitochondrial complex I activity in a mouse model. Int. J. Cardiol. 2018, 266, 206–212.

- Naito, Y.; Tsujino, T.; Matsumoto, M.; Sakoda, T.; Ohyanagi, M.; Masuyama, T. Adaptive response of the heart to long-term anemia induced by iron deficiency. Am. J. Physiol.—Heart Circ. Physiol. 2009, 296, 585–593.

- Tanne, Z.; Coleman, R.; Nahir, M.; Shomrat, D.; Finberg, J.P.M.; Youdim, M.B.H. Ultrastructural and cytochemical changes in the heart of iron-deficient rats. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1994, 47, 1759–1766.

- Kobak, K.A.; Radwańska, M.; Dzięgała, M.; Kasztura, M.; Josiak, K.; Banasiak, W.; Ponikowski, P.; Jankowska, E.A. Structural and functional abnormalities in iron-depleted heart. Heart Fail. Rev. 2019, 24, 269–277.

- Chung, Y.J.; Luo, A.; Park, K.C.; Loonat, A.A.; Lakhal-Littleton, S.; Robbins, P.A.; Swietach, P. Iron-deficiency anemia reduces cardiac contraction by downregulating RyR2 channels and suppressing SERCA pump activity. JCI Insight 2019, 4, e125618.

- Haddad, S.; Wang, Y.; Galy, B.; Korf-Klingebiel, M.; Hirsch, V.; Baru, A.M.; Rostami, F.; Reboll, M.R.; Heineke, J.; Flögel, U.; et al. Iron-regulatory proteins secure iron availability in cardiomyocytes to prevent heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 38, ehw333.

- Martens, P.; Verbrugge, F.H.; Nijst, P.; Dupont, M.; Mullens, W. Limited contractile reserve contributes to poor peak exercise capacity in iron-deficient heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2018, 20, 806–808.

- Núñez, J.; Miñana, G.; Cardells, I.; Palau, P.; Llàcer, P.; Fácila, L.; Almenar, L.; López-Lereu, M.P.; Monmeneu, J.V.; Amiguet, M.; et al. Noninvasive Imaging Estimation of Myocardial Iron Repletion Following Administration of Intravenous Iron: The Myocardial-IRON Trial. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e014254.

- Grote Beverborg, N.; Van Der Wal, H.H.; Klip, I.T.; Anker, S.D.; Cleland, J.; Dickstein, K.; Van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Voors, A.A.; Van Der Meer, P. Differences in Clinical Profile and Outcomes of Low Iron Storage vs. Defective Iron Utilization in Patients with Heart Failure: Results from the DEFINE-HF and BIOSTAT-CHF Studies. JAMA Cardiol. 2019, 4, 696–701.

- Petrak, J.; Havlenova, T.; Krijt, M.; Behounek, M.; Franekova, J.; Cervenka, L.; Pluhacek, T.; Vyoral, D.; Melenovsky, V. Myocardial iron homeostasis and hepcidin expression in a rat model of heart failure at different levels of dietary iron intake. Biochim. Biophys. Acta—Gen. Subj. 2019, 1863, 703–713.

- Santas, E.; Miñana, G.; Cardells, I.; Palau, P.; Llàcer, P.; Fácila, L.; Almenar, L.; López-Lereu, M.P.; Monmeneu, J.V.; Sanchis, J.; et al. Short-term changes in left and right systolic function following ferric carboxymaltose: A substudy of the Myocardial-IRON trial. ESC Heart Fail. 2020, 7, 4222–4230.

- Toblli, J.E.; Di Gennaro, F.; Rivas, C. Changes in echocardiographic parameters in iron deficiency patients with heart failure and chronic kidney disease treated with intravenous iron. Heart Lung Circ. 2015, 24, 686–695.

- Usmanov, R.I.; Zueva, E.B.; Silverberg, D.S.; Shaked, M. Intravenous iron without erythropoietin for the treatment of iron deficiency anemia in patients with moderate to severe congestive heart failure and chronic kidney insufficiency. J. Nephrol. 2008, 21, 2236–2242.

- Gaber, R.; Kotb, N.A.; Ghazy, M.; Nagy, H.M.; Salama, M.; Elhendy, A. Tissue doppler and strain rate imaging detect improvement of myocardial function in iron deficient patients with congestive heart failure after Iron replacement therapy. Echocardiography 2012, 29, 13–18.

- Núñez, J.; Monmeneu, J.V.; Mollar, A.; Núñez, E.; Bodí, V.; Miñana, G.; García-Blas, S.; Santas, E.; Agüero, J.; Chorro, F.J.; et al. Left ventricular ejection fraction recovery in patients with heart failure treated with intravenous iron: A pilot study. ESC Heart Fail. 2016, 3, 293–298.

- Martens, P.; Verbrugge, F.; Nijst, P.; Dupont, M.; Tang, W.H.W.; Mullens, W. Impact of Iron Deficiency on Response to and Remodeling After Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy. Am. J. Cardiol. 2017, 119, 65–70.

- Lacour, P.; Dang, P.L.; Morris, D.A.; Parwani, A.S.; Doehner, W.; Schuessler, F.; Hohendanner, F.; Heinzel, F.R.; Stroux, A.; Tschoepe, C.; et al. The effect of iron deficiency on cardiac resynchronization therapy: Results from the RIDE-CRT Study. ESC Heart Fail. 2020, 7, 1072–1084.

- Nijst, P.; Martens, P.; Mullens, W. Heart Failure with Myocardial Recovery—The Patient Whose Heart Failure Has Improved: What Next? Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2017, 60, 226–236.

- Chang, H.C.; Shapiro, J.S.; Ardehali, H. Getting to the “heart” of Cardiac Disease by Decreasing Mitochondrial Iron. Circ. Res. 2016, 119, 1164–1166.

- Lupu, M.; Tudor, D.V.; Filip, G.A. Influence of mitochondrial and systemic iron levels in heart failure pathology. Heart Fail. Rev. 2019, 24, 647–659.

- Sawicki, K.T.; Shang, M.; Wu, R.; Chang, H.C.; Khechaduri, A.; Sato, T.; Kamide, C.; Liu, T.; Naga Prasad, S.V.; Ardehali, H. Increased Heme Levels in the Heart Lead to Exacerbated Ischemic Injury. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2015, 4, e002272.

- Khechaduri, A.; Bayeva, M.; Chang, H.C.; Ardehali, H. Heme levels are increased in human failing hearts. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 61, 1884–1893.

- Mancini, D.M.; Walter, G.; Reichek, N.; Lenkinski, R.; McCully, K.K.; Mullen, J.L.; Wilson, J.R. Contribution of skeletal muscle atrophy to exercise intolerance and altered muscle metabolism in heart failure. Circulation 1992, 85, 1364–1373.

- Stugiewicz, M.; Tkaczyszyn, M.; Kasztura, M.; Banasiak, W.; Ponikowski, P.; Jankowska, E.A. The influence of iron deficiency on the functioning of skeletal muscles: Experimental evidence and clinical implications. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2016, 18, 762–773.

- Haas, J.D.; Brownlie IV, T. Iron deficiency and reduced work capacity: A critical review of the research to determine a causal relationship. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 676S–690S.

- Finch, C.A.; Miller, L.R.; Inamdar, A.R.; Person, R.; Seiler, K.; Mackler, B. Iron deficiency in the rat. Physiological and biochemical studies of muscle dysfunction. J. Clin. Invest. 1976, 58, 447–453.

- Rineau, E.; Gueguen, N.; Procaccio, V.; Geneviève, F.; Reynier, P.; Henrion, D.; Lasocki, S. Iron deficiency without anemia decreases physical endurance and mitochondrial complex i activity of oxidative skeletal muscle in the mouse. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1056.

- Burden, R.J.; Morton, K.; Richards, T.; Whyte, G.P.; Pedlar, C.R. Is iron treatment beneficial in, irondeficient but nonanaemic (IDNA) endurance athletes? A systematic review and metaanalysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 1389–1397.

- Barrientos, T.; Laothamatas, I.; Koves, T.R.; Soderblom, E.J.; Bryan, M.; Moseley, M.A.; Muoio, D.M.; Andrews, N.C. Metabolic Catastrophe in Mice Lacking Transferrin Receptor in Muscle. EBioMedicine 2015, 2, 1705–1717.

- Ponikowski, P.; Van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Comin-Colet, J.; Ertl, G.; Komajda, M.; Mareev, V.; McDonagh, T.; Parkhomenko, A.; Tavazzi, L.; Levesque, V.; et al. Beneficial effects of long-term intravenous iron therapy with ferric carboxymaltose in patients with symptomatic heart failure and iron deficiency. Eur. Heart J. 2015, 36, 657–668.

- Charles-Edwards, G.; Amaral, N.; Sleigh, A.; Ayis, S.; Catibog, N.; McDonagh, T.; Monaghan, M.; Amin-Youssef, G.; Kemp, G.J.; Shah, A.M.; et al. Effect of Iron Isomaltoside on Skeletal Muscle Energetics in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure and Iron Deficiency: FERRIC-HF II Randomized Mechanistic Trial. Circulation 2019, 139, 2386–2398.

- Forbes, J.M.; Thorburn, D.R. Mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2018, 14, 291–312.

- Thévenod, F.; Lee, W.K.; Garrick, M.D. Iron and Cadmium Entry Into Renal Mitochondria: Physiological and Toxicological Implications. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 848.

- Van Swelm, R.P.L.; Wetzels, J.F.M.; Swinkels, D.W. The multifaceted role of iron in renal health and disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2020, 16, 77–98.

- Del Greco, F.M.; Foco, L.; Pichler, I.; Eller, P.; Eller, K.; Benyamin, B.; Whitfield, J.B.; Pramstaller, P.P.; Thompson, J.R.; Pattaro, C.; et al. Serum iron level and kidney function: A Mendelian randomization study. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2017, 32, 273–278.

- El-Shimi, M.S.; El-Farrash, R.A.; Ismail, E.A.; El-Safty, A.; Nada, A.S.; El-Gamel, O.A.; Salem, Y.M.; Shoukry, S.M. Renal functional and structural integrity in infants with iron deficiency anemia: Relation to oxidative stress and response to iron therapy. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2015, 30, 1835–1842.

- Toblli, J.E.; Lombraña, A.; Duarte, P.; Di Gennaro, F. Intravenous Iron Reduces NT-Pro-Brain Natriuretic Peptide in Anemic Patients With Chronic Heart Failure and Renal Insufficiency. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2007, 50, 1657–1665.

- Ponikowski, P.; Filippatos, G.; Colet, J.C.; Willenheimer, R.; Dickstein, K.; Lüscher, T.; Gaudesius, G.; Von Eisenhart Rothe, B.; Mori, C.; Greenlaw, N.; et al. The impact of intravenous ferric carboxymaltose on renal function: An analysis of the FAIR-HF study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2015, 17, 329–339.

- Stöhr, R.; Sandstede, L.; Heine, G.H.; Marx, N.; Brandenburg, V. High-Dose Ferric Carboxymaltose in Patients With HFrEF Induces Significant Hypophosphatemia. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 2270–2271.

- Courbon, G.; Martinez-Calle, M.; David, V. Simultaneous management of disordered phosphate and iron homeostasis to correct fibroblast growth factor 23 and associated outcomes in chronic kidney disease. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2020, 29, 359–366.

- Stöhr, R.; Schuh, A.; Heine, G.H.; Brandenburg, V. FGF23 in cardiovascular disease: Innocent bystander or active mediator? Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 351.

- Lanser, L.; Fuchs, D.; Kurz, K.; Weiss, G. Physiology and inflammation driven pathophysiology of iron homeostasis—mechanistic insights into anemia of inflammation and its treatment. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3732.

- Van der Wal, H.H.; Beverborg, N.G.; ter Maaten, J.M.; Vinke, J.S.J.; de Borst, M.H.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; Voors, A.A.; van der Meer, P. Fibroblast growth factor 23 mediates the association between iron deficiency and mortality in worsening heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2020, 22, 903–906.

- Mu, Q.; Chen, L.; Gao, X.; Shen, S.; Sheng, W.; Min, J.; Wang, F. The role of iron homeostasis in remodeling immune function and regulating inflammatory disease. Sci. Bull. 2021, 66, 1806–1816.

- Cherayil, B.J. Iron and immunity: Immunological consequences of iron deficiency and overload. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 2010, 58, 407–415.

- Weiss, G. Iron and Immunity: A Double-Edged Sword. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2002, 32, 70–78.

- Ward, R.J.; Crichton, R.R.; Taylor, D.L.; Della Corte, L.; Srai, S.K.; Dexter, D.T. Iron and the immune system. J. Neural Transm. 2011, 118, 315–328.

- Cronin, S.J.F.; Woolf, C.J.; Weiss, G.; Penninger, J.M. The Role of Iron Regulation in Immunometabolism and Immune-Related Disease. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2019, 6, 116.

- Howden, A.J.M.; Hukelmann, J.L.; Brenes, A.; Spinelli, L.; Sinclair, L.V.; Lamond, A.I.; Cantrell, D.A. Quantitative analysis of T cell proteomes and environmental sensors during T cell differentiation. Nat. Immunol. 2019, 20, 1542–1554.

- Omara, F.O.; Blakley, B.R. The effects of iron deficiency and iron overload on cell-mediated immunity in the mouse. Br. J. Nutr. 1994, 72, 899–909.

- Spear, A.T.; Sherman, A.R. Iron deficiency alters DMBA-induced tumor burden and natural killer cell cytotoxicity in rats. J. Nutr. 1992, 122, 46–55.

- Ganz, T.; Nemeth, E. Iron homeostasis in host defence and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 500–510.

- Pagani, A.; Nai, A.; Corna, G.; Bosurgi, L.; Rovere-Querini, P.; Camaschella, C.; Silvestri, L. Low hepcidin accounts for the proinflammatory status associated with iron deficiency. Blood 2011, 118, 736–746.

- Shayganfard, M. Are Essential Trace Elements Effective in Modulation of Mental Disorders? Update and Perspectives. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2021, 1–28.

- Ferreira, A.; Neves, P.; Gozzelino, R. Multilevel impacts of iron in the brain: The cross talk between neurophysiological mechanisms, cognition, and social behavior. Pharmaceuticals 2019, 12, 126.

- Todorich, B.; Pasquini, J.M.; Garcia, C.I.; Paez, P.M.; Connor, J.R. Oligodendrocytes and myelination: The role of iron. Glia 2009, 57, 467–478.

- Kim, J.; Wessling-Resnick, M. Iron and mechanisms of emotional behavior. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2014, 25, 1101–1107.

- Belmaker, R.H.; Agam, G. Major Depressive Disorder. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358, 55–68.

- Di Palo, K.E. Psychological Disorders in Heart Failure. Heart Fail. Clin. 2020, 16, 131–138.

- Barandiarán Aizpurua, A.; Sanders-van Wijk, S.; Brunner-La Rocca, H.P.; Henkens, M.T.H.M.; Weerts, J.; Spanjers, M.H.A.; Knackstedt, C.; van Empel, V.P.M. Iron deficiency impacts prognosis but less exercise capacity in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. ESC Heart Fail. 2021, 8, 1304–1313.

- Huang, K.W.; Bilgrami, N.L.; Hare, D.L. Iron Deficiency in Heart Failure Patients and Benefits of Iron Replacement on Clinical Outcomes Including Comorbid Depression. Heart Lung Circ. 2021.

- Vargas-Uricoechea, H.; Bonelo-Perdomo, A. Thyroid Dysfunction and Heart Failure: Mechanisms and Associations. Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. 2017, 14, 48–58.

- Razvi, S.; Jabbar, A.; Pingitore, A.; Danzi, S.; Biondi, B.; Klein, I.; Peeters, R.; Zaman, A.; Iervasi, G. Thyroid Hormones and Cardiovascular Function and Diseases. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 1781–1796.

- Maldonado-Araque, C.; Valdés, S.; Lago-Sampedro, A.; Lillo-Muñoz, J.A.; Garcia-Fuentes, E.; Perez-Valero, V.; Gutierrez-Repiso, C.; Goday, A.; Urrutia, I.; Peláez, L.; et al. Iron deficiency is associated with Hypothyroxinemia and Hypotriiodothyroninemia in the Spanish general adult population: study. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6571.

- Beard, J.; Tobin, B.; Green, W. Evidence for thyroid hormone deficiency in iron-deficient anemic rats. J. Nutr. 1989, 119, 772–778.

- Crielaard, B.J.; Lammers, T.; Rivella, S. Targeting iron metabolism in drug discovery and delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 400–423.

- Anand, I.S.; Gupta, P. Anemia and Iron Deficiency in Heart Failure: Current Concepts and Emerging Therapies. Circulation 2018, 138, 80–98.

- Sheetz, M.; Barrington, P.; Callies, S.; Berg, P.H.; McColm, J.; Marbury, T.; Decker, B.; Dyas, G.L.; Truhlar, S.M.E.; Benschop, R.; et al. Targeting the hepcidin–ferroportin pathway in anaemia of chronic kidney disease. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 85, 935–948.

- Pergola, P.E.; Devalaraja, M.; Fishbane, S.; Chonchol, M.; Mathur, V.S.; Smith, M.T.; Lo, L.; Herzog, K.; Kakkar, R.; Davidson, M.H. Ziltivekimab for treatment of anemia of inflammation in patients on hemodialysis: Results from a phase 1/2 multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2021, 32, 211–222.

- Alnuwaysir, R.I.S.; Grote Beverborg, N.; Hoes, M.F.; Markousis-Mavrogenis, G.; Gomez, K.A.; Wal, H.H.; Cleland, J.G.F.; Dickstein, K.; Lang, C.C.; Ng, L.L.; et al. Additional Burden of Iron Deficiency in Heart Failure Patients beyond the Cardio-Renal-Anaemia Syndrome: Findings from the BIOSTAT-CHF Study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2021.

- Crugliano, G.; Serra, R.; Ielapi, N.; Battaglia, Y.; Coppolino, G.; Bolignano, D.; Bracale, U.M.; Pisani, A.; Faga, T.; Michael, A.; et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor stabilizers in end stage kidney disease: “Can the promise be kept”? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12590.

- Liu, J.; Zhang, A.; Hayden, J.C.; Bhagavathula, A.S.; Alshehhi, F.; Rinaldi, G.; Kontogiannis, V.; Rahmani, J. Roxadustat (FG-4592) treatment for anemia in dialysis-dependent (DD) and not dialysis-dependent (NDD) chronic kidney disease patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 155, 104747.

- Chen, H.; Cheng, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, S. Long-term efficacy and safety of hypoxia-inducible factor prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors in anaemia of chronic kidney disease: A meta-analysis including 13,146 patients. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2021, 46, 999–1009.

- Provenzano, R.; Besarab, A.; Wright, S.; Dua, S.; Zeig, S.; Nguyen, P.; Poole, L.; Saikali, K.G.; Saha, G.; Hemmerich, S.; et al. Roxadustat (FG-4592) versus epoetin alfa for anemia in patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis: A phase 2, randomized, 6- to 19-week, open-label, active-comparator, dose-ranging, safety and exploratory efficacy study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2016, 67, 912–924.

- Haase, V.H. HIF-prolyl hydroxylases as therapeutic targets in erythropoiesis and iron metabolism. Hemodial. Int. 2017, 21, S110–S124.