Though diversity among cardiothoracic surgeons performing pediatric and adult heart transplantations (HTxs) has increased over the past years, the majority of the field remains male and White. This is particularly striking when compared with the composition of the United States population (49.2% male, 60.1% White in 2019). These findings are particularly important, given that prior studies have identified sex and racial disparities in access and outcomes following HTx among adult patients, and that racial concordance between physicians and patients improves patient outcomes in settings of known racial disparities. These results demonstrate the need for further research to analyze the causes of sex and racial disparities and initiate more effective efforts to increase diversity of the workforce.

1. Introduction

Historically, there has been a lack of female and non-White cardiothoracic surgeons. Several factors within surgical training such as racial discrimination, sexual discrimination, and harassment have been implicated in perpetuating this lack of diversity

[1][2]. Despite these factors, recent studies have demonstrated an increase in the number of female cardiothoracic surgeons

[3]; however, there is a paucity of literature regarding trends in the racial composition of the cardiothoracic surgeon workforce.

Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that patients undergoing cardiothoracic operations experience sex and racial disparities in care and outcomes

[4]. Similar patterns have also been observed among adult patients undergoing heart transplantation (HTx)

[5]. Increasing the diversity of the cardiothoracic surgery workforce is one potential approach towards mitigating these disparities. The findings of Greenwood and colleagues have supported this notion by demonstrating that physician–patient racial concordance was associated with improved infant survival after childbirth, which has demonstrable racial disparities in patient outcomes

[6]. In a similar study, Greenwood and colleagues found that female patients with acute myocardial infarction treated by female physicians had better outcomes than when treated by male physicians

[7]. Moreover, Wallis et al. recently demonstrated that surgeon–patient sex discordance adversely affected outcomes of common surgical procedures

[8].

2. Adult Heart Transplant Surgeon Workforce

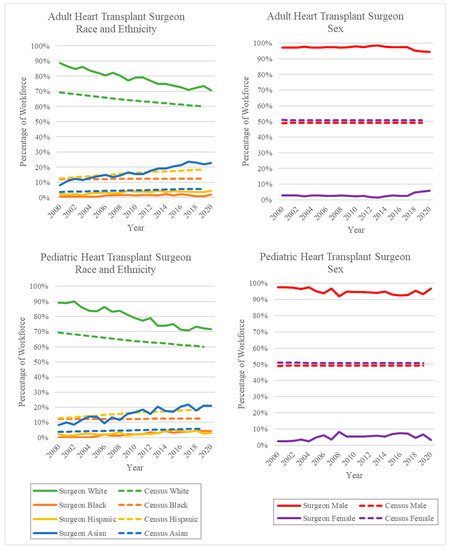

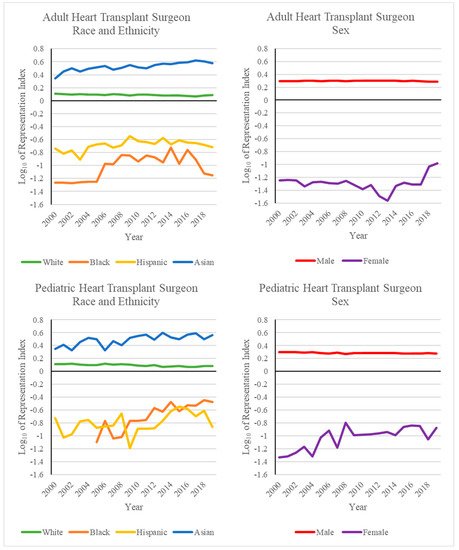

The diversity of the adult HTx workforce has increased over the past 20 years. The majority of surgeons in this workforce remain White, although the percentage of White adult HTx surgeons decreased from 88.8% in 2000 to 73.6% in 2019. This roughly mirrors the rate of change of the White population of the United States from 69.4% to 60.1% in the same time period

[9][10]. Despite this decrease, the percentage of White adult HTx surgeons was higher than the percentage of the White population of the United States for the entire study period (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). The percentage of Asian adult HTx surgeons similarly exceeded the percentage of the Asian population of the US throughout the study period. However, unlike White adult HTx surgeons, the percentage of Asian adult HTx surgeons increased during the study period. Asian adult HTx surgeons comprised 8.2% of the workforce in 2000 and 22.0% in 2019, compared to US Asian population percentages of 3.7% in 2000 and 5.8% in 2019

[9][10]. The percentages of Black and Hispanic adult HTx surgeons remained far below their respective US population percentages during the study period. The percentage of Black adult HTx surgeons increased from 0.7% in 2000 to 2.0% in 2020. The percentage of Hispanic adult HTx surgeons also increased, from 2.3% in 2000 to 4.4% in 2020.

Figure 1. Percentage of workforce by year of surgeons performing at least one HTx. Solid lines represent the HTx surgeon workforce percentage, and dashed lines represent the US population percentages as reported by the US Census

[9][10].

Figure 2. Common logarithm of the representation index by year of surgeons performing at least one HTx. Values greater than zero indicate overrepresentation, and values less than zero indicate underrepresentation. The representation index was calculated with respect to US Census data

[9][10].

The majority of adult HTx surgeons during the study period were male. Female surgeons comprised 2.9% of the workforce in 2000 and 5.7% in 2020. The percentage of female adult HTx surgeons remained relatively constant from 2000 to 2017 (2.9% and 2.5%, respectively). However, a substantial uptick in the percentage of female adult HTx surgeons occurred between 2017 and 2018, where the percentage of female HTx surgeons increased from 2.5% to 4.7%.

3. Pediatric Heart Transplant Surgeon Workforce

The diversity of the pediatric HTx workforce similarly increased over the past 20 years. The majority of the pediatric HTx workforce remains White. Despite this, the percentage of White pediatric HTx surgeons decreased from 89.3% in 2000 to 72.3% in 2019. The percentage of White pediatric HTx surgeons remained higher than the White population percentage of the US over the entire study period (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Similarly, the percentage of Asian pediatric HTx surgeons remained higher than the percentage of the Asian population of the US over the same period. The percentage of Asian pediatric HTx surgeons increased from 8.3% in 2000 to 21.0% in 2019. The percentage of Black and Hispanic pediatric HTx surgeons fell far below their respective US population percentages. The percentage of Black pediatric HTx surgeons increased from 0.0% in 2000 to 4.2% in 2020. It is worth noting that prior to 2005 in this research, there were no Black pediatric HTx surgeons. The percentage of Hispanic pediatric HTx surgeons increased from 2.4% in 2000 to 3.2% in 2020.

The majority of pediatric HTx surgeons between 2000 and 2020 were male. The percentage of female HTx surgeons remained relatively constant between 2000 and 2020. The percentage of female HTx surgeons increased from 2.4% in 2000 to 3.2% in 2020.

4. Trends in Diversity

When looking at the distribution of HTxs by race and ethnicity, it was found that Black and Hispanic surgeons have remained far below their respective US population percentages in the context of both adult and pediatric HTxs. This trend is likely partially due to there being less Black and Hispanic students entering medical school; therefore, there are fewer applicants for positions as HTx surgeons

[11]. The proportion of Asian surgeons, on the other hand, has remained above the respective proportion of Asians in the US population. This could be due to cardiac transplants being typically performed at academic centers at which Asian surgical faculty have been previously found to be overrepresented when compared with the US population

[12].

The analysis by sex found that the number of female HTx surgeons remained below 5% from 2000–2020. The greatest increase, from 2.5% to 4.7%, was seen from 2017 to 2018 in the context of adult HTxs. This could have been an effect of the steady increase in the number of women in cardiothoracic surgery as a specialty from the year 2000. Additionally, more integrated and fast-track residency programs in cardiothoracic surgery have been created in the past few years

[13]. These could be serving as an incentive for women to enter the field, as they allow completion of training in a shorter amount of time. This differs from the discrepancy between the HTx percentages when looking at race and ethnicity, because medical schools do not lack in the representation of women as they do with minority populations. This indicates that there could be a problem during medical school in recruiting women to cardiothoracic surgery, rather than a problem with accepting women to medical school, as is the case with minority individuals.

The general United States population was used as a baseline rather than the practicing physician population because the barriers that exist to becoming a cardiothoracic transplant surgeon also exist for other subspecialties in medicine. Social determinants of health, such as income and access to education, affect the general population from entering the practicing physician population

[14]. Structural racism, discrimination, and implicit bias exist as barriers that impact minorities within the medical community

[15]. Additionally, a physician workforce should be representative of the population it stems from and serves. The practicing physician population must be explored in its entirety for new trends in diversity before it can be used as a baseline population for a subspecialty of physicians.

This research led to more information about the trends in diversity over the last 20 years within the cardiothoracic surgery workforce in the context of heart transplantation. It was generalized across the entire United States, but it would be interesting to investigate how historical patterns affect the sex and racial disparities across different regions in the United States that are seen today. For example, it could be theorized that there could be a higher proportion of Black surgeons in the Southeastern United States in the current day due to the transatlantic slave trade. Immigration patterns of different races and ethnicities should be explored as well, as minority status is separate from immigration status. The lack of diversity present in the cardiothoracic surgery workforce in the context of heart transplants demonstrates the need to investigate the demographic patterns in other sub-specialized fields of medicine to determine whether this lack of diversity is present across the board, or whether it is only occurring in some fields such as surgery as whole

[16]. Future implications of this type of research include investigating the need for policy changes at institutional, community, and societal levels to address this lack of diversity. There should be incentives and support provided for underrepresented individuals at each of these levels of healthcare. These findings serve as objective data illustrating the need for more research to analyze the root of the disparities seen in cardiothoracic surgery.