Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yasuka Matsunaga | -- | 2774 | 2022-04-06 17:24:02 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | Meta information modification | 2774 | 2022-04-07 04:26:34 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Matsunaga, Y.; Inoue, M.; Nakatsu, Y.; Yamamotoya, T.; , .; Sakoda, H.; Fujishiro, M.; Ono, H.; Asano, T. Pin1. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21425 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Matsunaga Y, Inoue M, Nakatsu Y, Yamamotoya T, , Sakoda H, et al. Pin1. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21425. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Matsunaga, Yasuka, Masa-Ki Inoue, Yusuke Nakatsu, Takeshi Yamamotoya, , Hideyuki Sakoda, Midori Fujishiro, Hiraku Ono, Tomoichiro Asano. "Pin1" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21425 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Matsunaga, Y., Inoue, M., Nakatsu, Y., Yamamotoya, T., , ., Sakoda, H., Fujishiro, M., Ono, H., & Asano, T. (2022, April 06). Pin1. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21425

Matsunaga, Yasuka, et al. "Pin1." Encyclopedia. Web. 06 April, 2022.

Copy Citation

Pin1 is one of the three known prolyl-isomerase types and its hepatic expression level is markedly enhanced in the obese state. Pin1 plays critical roles in favoring the exacerbation of both lipid accumulation and fibrotic change accompanying inflammation.

Pin1

NASH

NAFLD

fibrosis

lipid

1. Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is characterized as hepatic steatosis that is not caused by factors such as significant alcohol consumption, chronic viral hepatitis and the side effects of medicines. In recent years, the number of NAFLD patients has been rising, showing trends similar to those of other diseases included in the metabolic syndrome category. In addition, approximately 10% of these NAFLD patients are categorized as suffering from nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which is characterized by inflammatory steatosis and fibrosis, eventually progressing to liver cirrhosis and/or cancer [1][2]. NASH/NAFLD patients are currently estimated to comprise 20–40% of the global population [3][4][5][6]. Several clinical studies have suggested that dietary and exercise therapies for NASH/NAFLD improve biochemical indicators but do not ameliorate liver fibrosis [7][8].

Accordingly, various drugs, such as antidiabetic agents, have been studied as potential treatments for NASH/NAFLD. However, there are still no drugs that have gained general acceptance for treating NASH/NAFLD. Therefore, the elucidation of the molecular mechanisms underlying NASH development is essential for developing novel treatments [9][10][11][12][13][14], which should also be based on confirmed clinical evidence. Regarding these molecular mechanisms, the abnormalities impacting transcriptional factors, signal transduction molecules and post-translational modifications of these factors have been extensively investigated [3].

On the other hand, peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase Pin1 has the unique feature of associating with the domain containing the phospho-serine/proline or the phospho-threonine/proline motif, unlike the other prolyl isomerases (PPIases), e.g., FK506 Binding Protein and cyclophilin. Pin1 reportedly affects the function, stability and/or subcellular localization of its target proteins and thereby controls cellular proliferation, metabolism, fibrosis and inflammation [15]. The proline-directed serine/threonine phosphorylations are reportedly carried out by kinases such as cyclin-dependent kinases and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) [16][17][18]. Therefore, the Pin1 expression level, as well as the phosphorylating activities mediated by serine/threonine-directed kinases, are important for the cis/trans isomerization at the proline residue of target proteins [19][20][21].

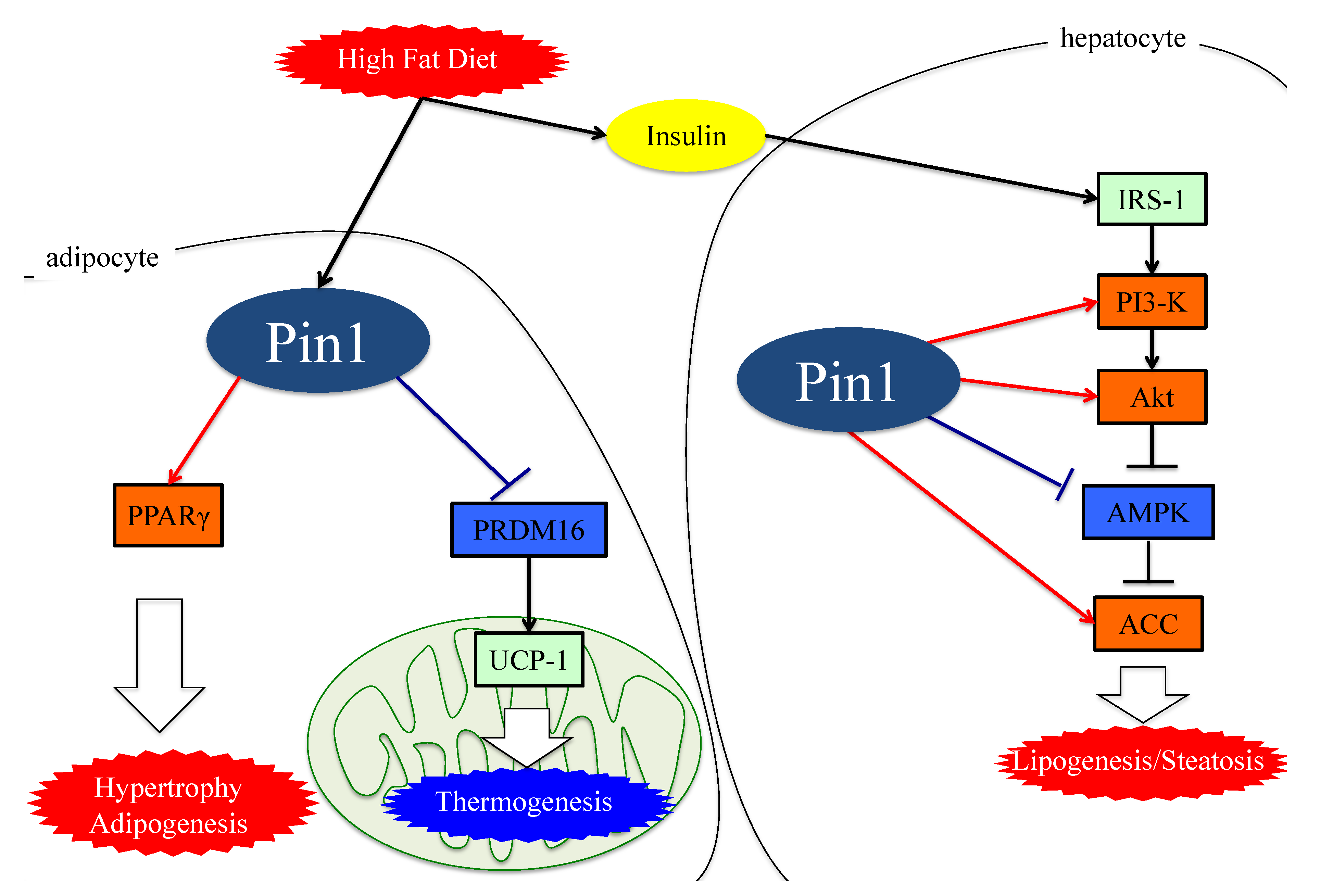

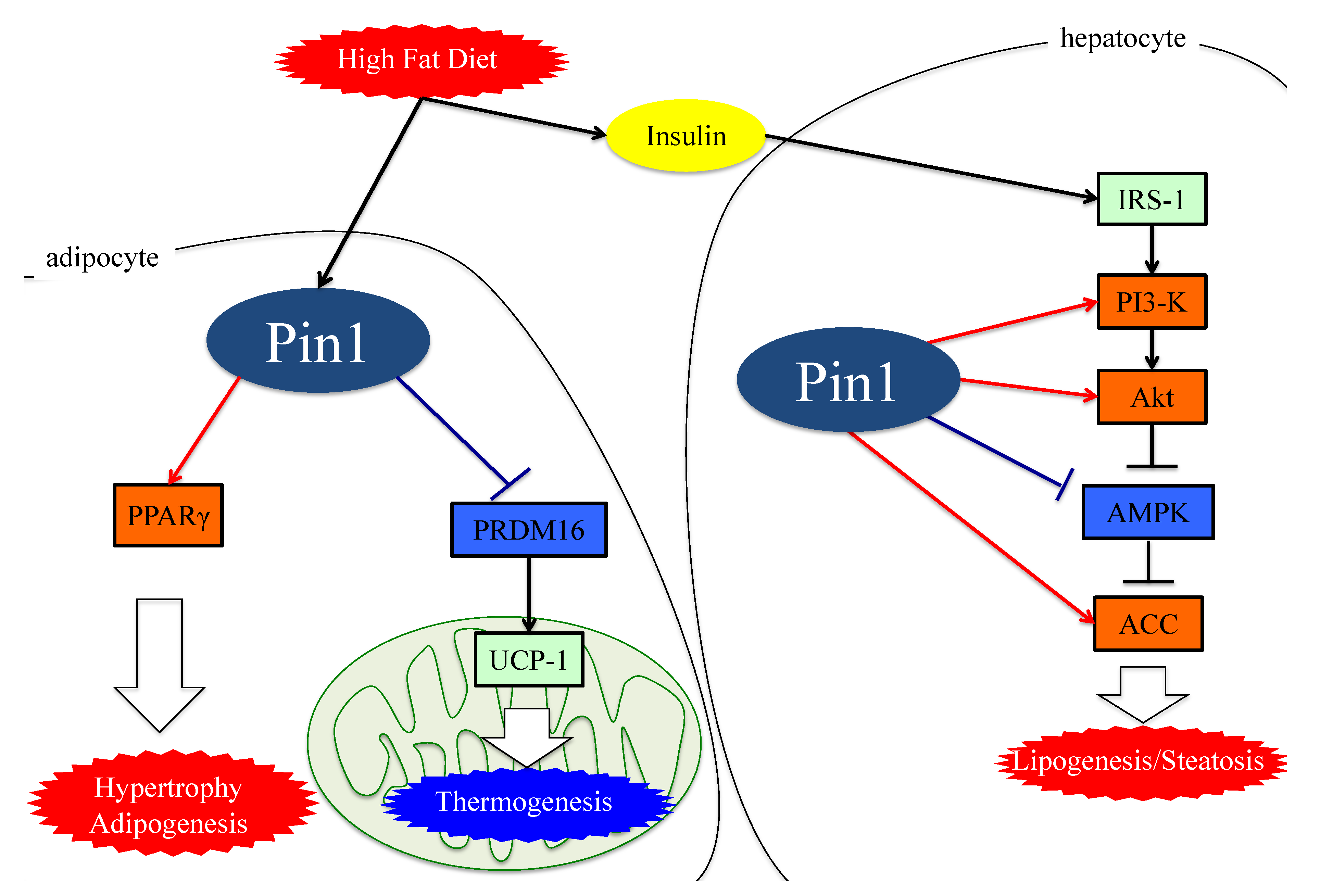

Figure 1. The functions of Pin1 in the molecular mechanism of lipogenesis in adipocytes. Either an HFD or MCDD increases Pin1 expressions in the liver and adipocytes. In adipocytes and hepatocytes, Pin1 enhances lipogenesis through an insulin-signaling-dependent mechanism by associating with IRS-1 and Akt, exerting AMPK-dependent and direct actions on lipid enzymes such as ACC1 and FASN. In the energy consumption pathway, Pin1 downregulates the expressions of thermogenic genes, such as UCP-1, and reduces O2 consumption. Pin1 also enhances adipocyte differentiation by activating transcription of PPARγ protein in adipocytes. IRS-1: insulin receptor substrate 1. ACC: acetyl CoA carboxylase. PRDM16: PR domain containing 16. UCP-1: Uncoupling protein 1. PPARγ: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ.

Figure 1. The functions of Pin1 in the molecular mechanism of lipogenesis in adipocytes. Either an HFD or MCDD increases Pin1 expressions in the liver and adipocytes. In adipocytes and hepatocytes, Pin1 enhances lipogenesis through an insulin-signaling-dependent mechanism by associating with IRS-1 and Akt, exerting AMPK-dependent and direct actions on lipid enzymes such as ACC1 and FASN. In the energy consumption pathway, Pin1 downregulates the expressions of thermogenic genes, such as UCP-1, and reduces O2 consumption. Pin1 also enhances adipocyte differentiation by activating transcription of PPARγ protein in adipocytes. IRS-1: insulin receptor substrate 1. ACC: acetyl CoA carboxylase. PRDM16: PR domain containing 16. UCP-1: Uncoupling protein 1. PPARγ: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ.

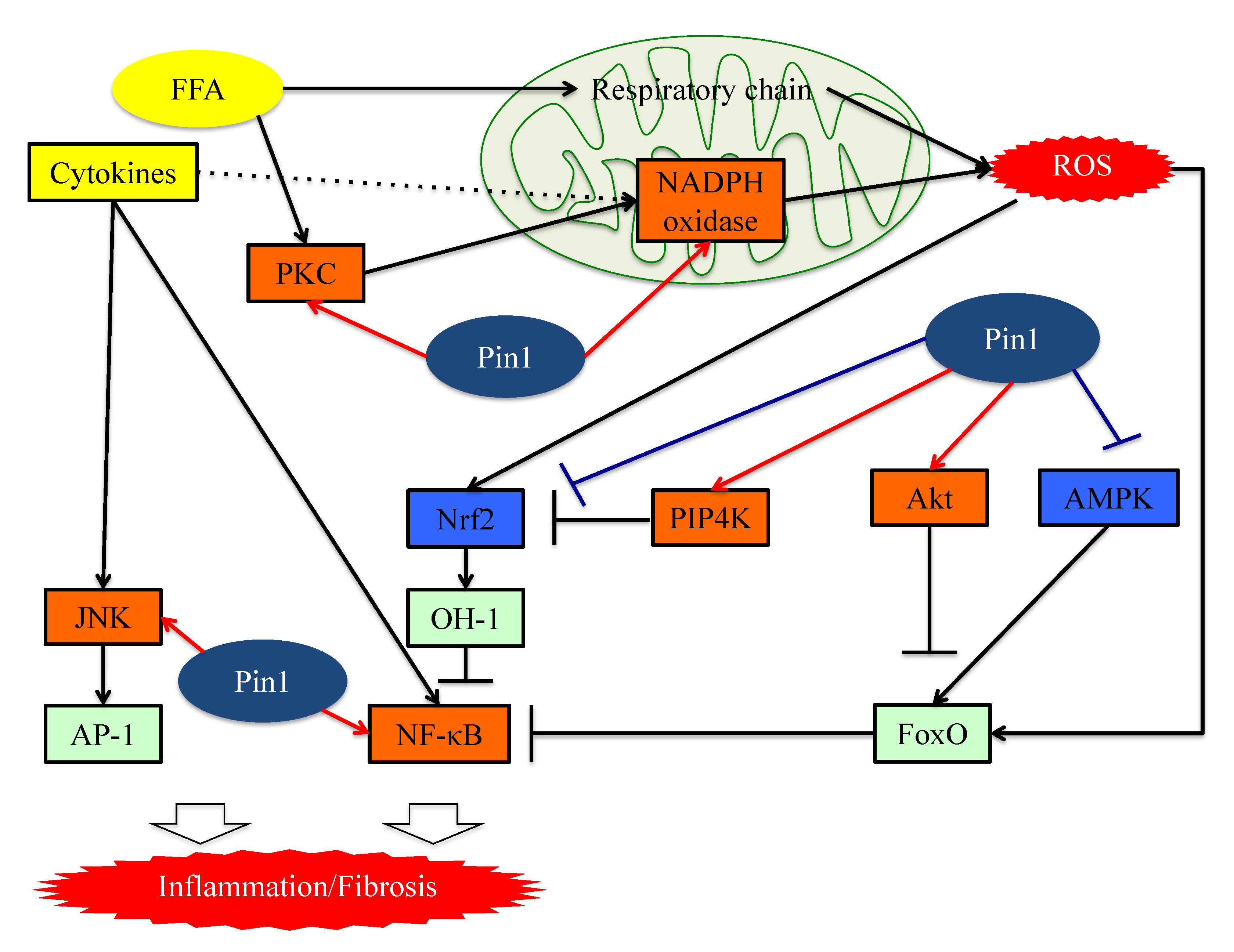

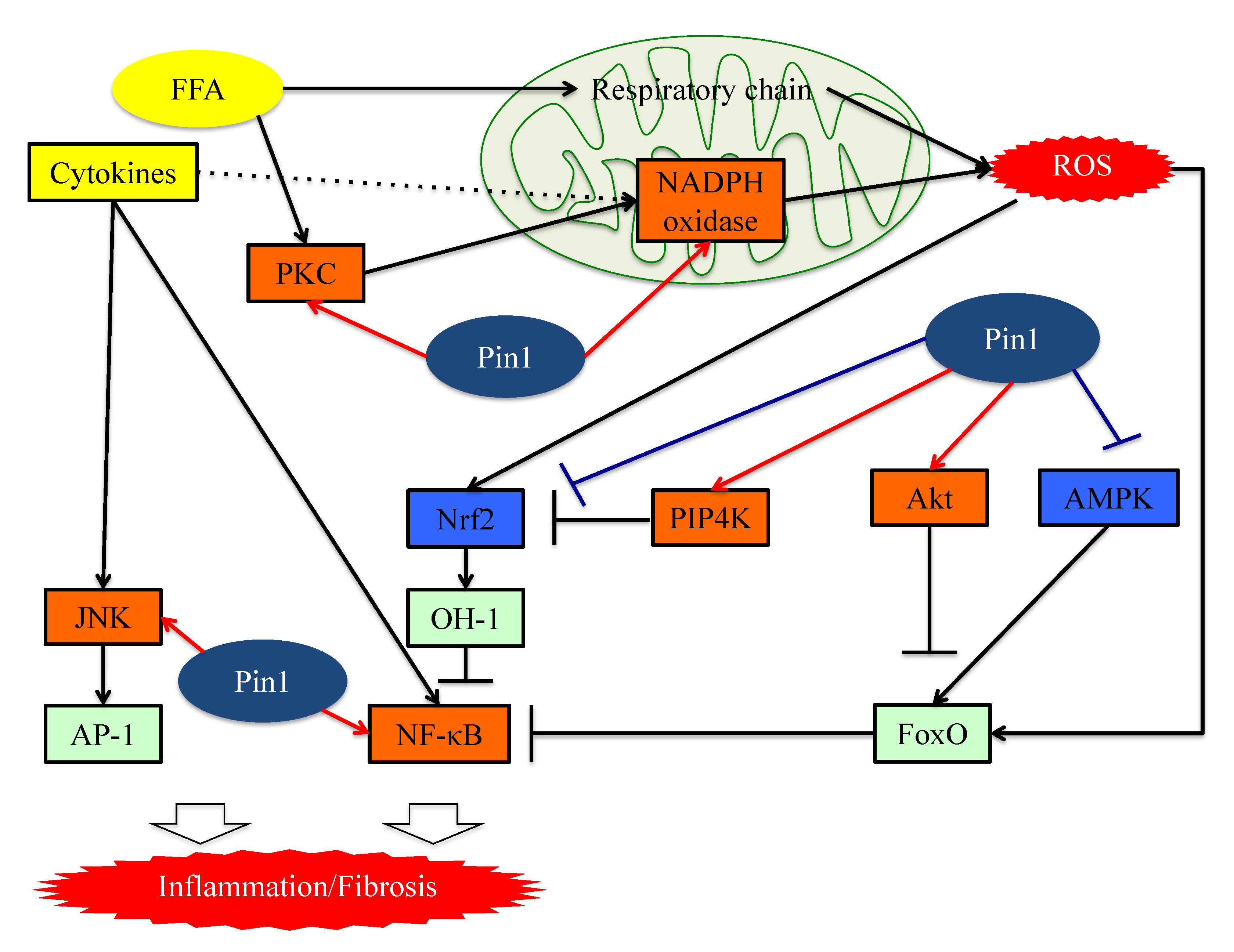

Figure 2. The functions of Pin1 in the molecular mechanism underlying inflammation in hepatocytes. Pin1 enhances superoxide production via NADPH oxidase activation and increases ROS production. In the downstream portion of this pathway, Pin1 inhibits the ROS resistant pathway and induces hepatic inflammation. Pin1 also activates the NF-κB and JNK-AP-1 pathways, thereby inducing hepatic inflammation. ROS: reactive oxygen species. FFA: Free fatty acid. FoxO: Forkhead box O. Nrf2: NFE2-related factor 2. NF-kB: nuclear factor-kB.

Figure 2. The functions of Pin1 in the molecular mechanism underlying inflammation in hepatocytes. Pin1 enhances superoxide production via NADPH oxidase activation and increases ROS production. In the downstream portion of this pathway, Pin1 inhibits the ROS resistant pathway and induces hepatic inflammation. Pin1 also activates the NF-κB and JNK-AP-1 pathways, thereby inducing hepatic inflammation. ROS: reactive oxygen species. FFA: Free fatty acid. FoxO: Forkhead box O. Nrf2: NFE2-related factor 2. NF-kB: nuclear factor-kB.

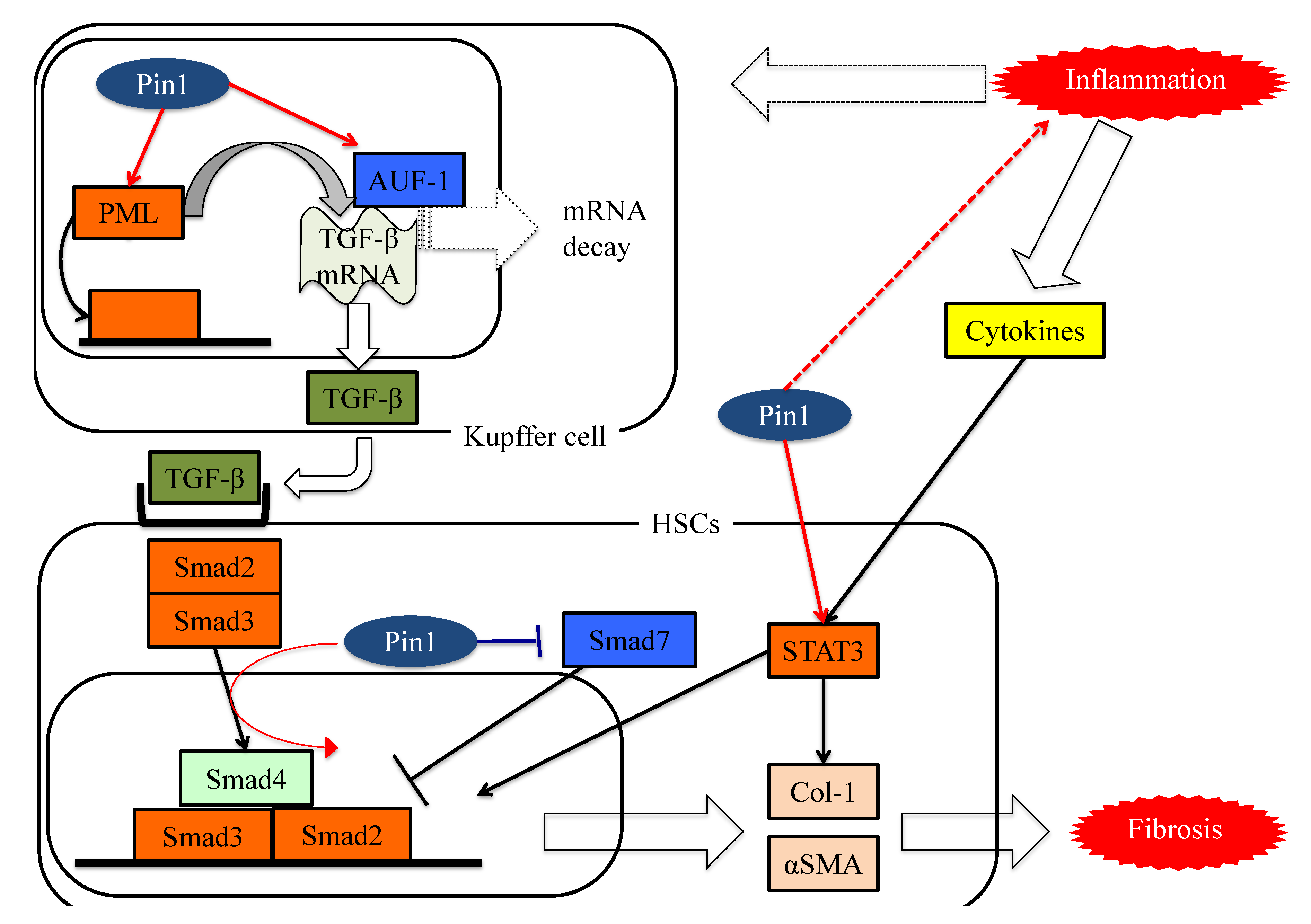

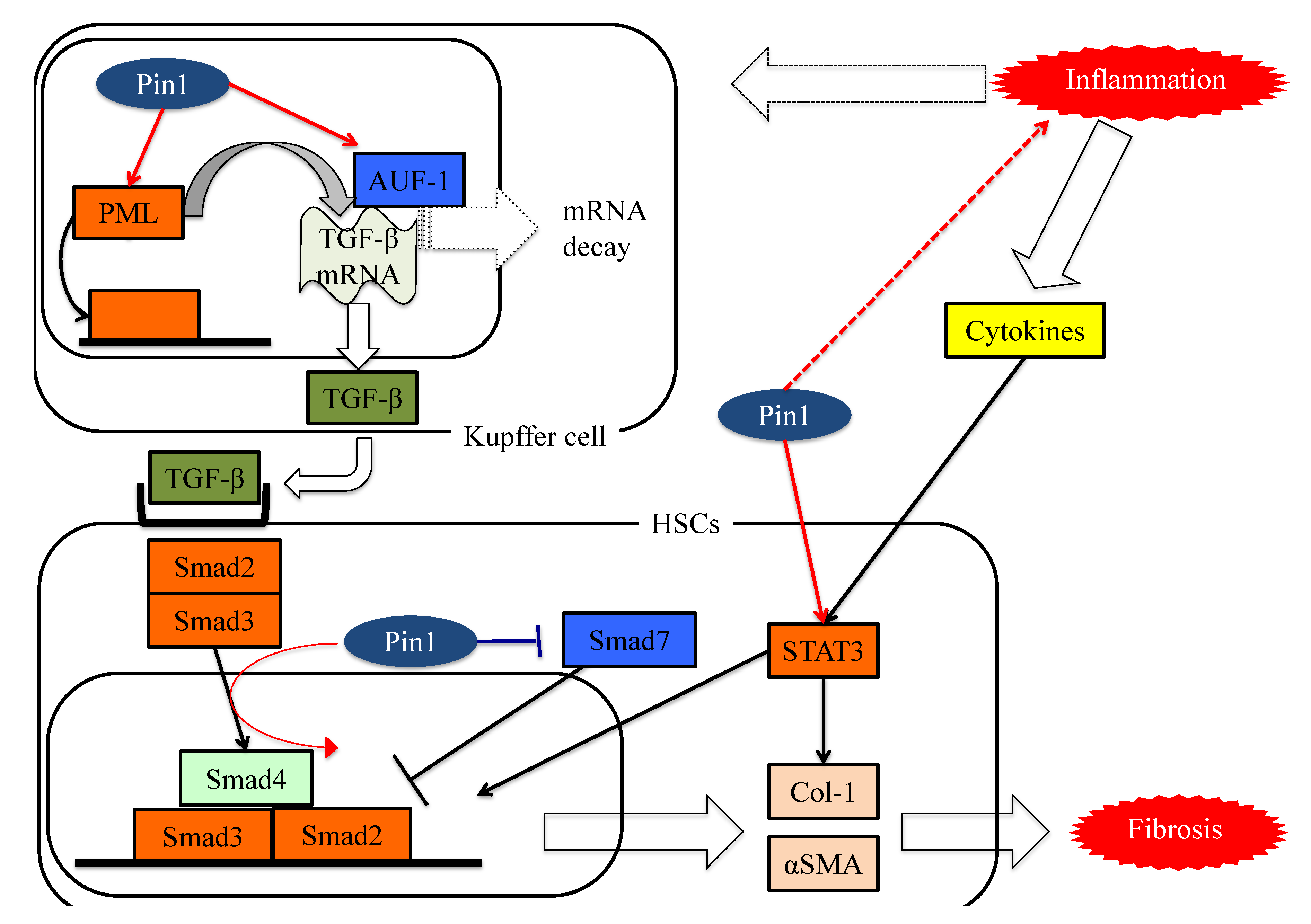

Figure 3. The functions of Pin1 in the molecular mechanism underlying fibrosis in HSCs. Pin1 activates TGF-β mRNA translation activity and the SMAD pathway in HSCs, which in turn activates extracellular matrix Col-1 and αSMA protein expression.

Figure 3. The functions of Pin1 in the molecular mechanism underlying fibrosis in HSCs. Pin1 activates TGF-β mRNA translation activity and the SMAD pathway in HSCs, which in turn activates extracellular matrix Col-1 and αSMA protein expression.

2. Prolyl Isomerase Pin1

Pin1 contains two functional domains which are connected by a flexible linker. Pin1 holds the WW domain (amino acids 1–39) in the N-terminal and the PPIase domain (amino acids 45–163) in the C-terminal [15][22][23][24]. In general, the WW domain associates with proline-rich sequences of target proteins. In the case of Pin1, however, phosphorylated Ser or Thr are required as the prior amino acid just before proline in order for binding to occur. The PPIase domain has the responsibility for isomerase activity.

Pin1 is expressed in various cells. In the liver, it has been experimentally shown that Pin1 is expressed at least in hepatocytes, Kupffer cells, and hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) [25][26]. As to liver diseases, Pin1 was first identified in liver cancer. Many studies have revealed a relationship between Pin1 and cancer. In fact, Pin1 strongly promotes both cancer development and growth through various pathways. In the cell cycle pathway, Pin1 increases cyclin D1 expression and thereby promotes cell cycle progression [27]. Pin1 also enhances the Notch signaling pathway. Pin1 activates Notch1 cleavage by the γ-secretase enzyme, thus increasing the release of the active intracellular domain and ultimately leading to the upregulation of both Notch1 transcriptional and tumorigenic activity [28]. In addition, the post-translational modification of Pin1 is thought to contribute to tumor formation in the liver. The phosphorylation of Pin1 Ser65 by Plk-1 is thought to stabilize Pin1 and promote carcinogenesis.

3. Role of Pin1 in the Pathogenesis of Hepatic Steatosis

Hepatic steatosis results from an imbalance between lipogenesis and fatty acid oxidation [29]. As described above, hepatic Pin1 expressions are increased by either an HFD or MCDD, and hepatic steatosis does not occur in Pin1 knockout (KO) mice [30]. These findings indicate Pin1 in the liver to be essential for the development of steatosis.

First, insulin signaling plays critical roles in lipogenesis, by inducing the expressions of two rate-limited enzymes, acetyl CoA carboxylase 1 (ACC1) and fatty acid synthase (FASN) [31][32]. Pin1 reportedly enhances insulin signaling via its association with insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1) and Akt [30][33]. Pin1 binds to IRS-1 and upregulates its tyrosine phosphorylation without altering IRS-1 protein levels. Indeed, Pin1 null mice were revealed to have impaired insulin sensitivity [30]. Moreover, Pin1 raises the level of Akt phosphorylation at Ser473 through the stabilization of the total Akt protein amount [32].

A recent report also clarified that Pin1 directly interacts with ACC1 and increases its protein stability [34]. Indeed, while Pin1 KO or knockdown markedly reduces the half-life of the ACC1 protein, Pin1 overexpression increases it. Similarly, the protein expression level of FASN is also increased by Pin1 without changing its mRNA level [35].

Third, Pin1 reportedly associates with the CBS domain in the γ subunit and reduces AMPKα subunit phosphorylation [36]. The reduction in AMPKα subunit phosphorylation mediated by Pin1 is likely due to the protective effect exerted by AMP or ADP, against dephosphorylation by protein phosphatase 2C (PP2C), being abolished. As a result, Pin1 negatively regulates AMPK activity [36]. AMPK, known as a major controller of lipid metabolism, directly phosphorylates ACC1 at the Ser79 site, and decreases both its activity and the productions of malonyl-CoA [37][38]. The reduction of malonyl-CoA indirectly upregulates fatty acid oxidation by abrogating the suppression of carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT-1) [39][40]. In other words, AMPK inhibits lipogenesis and enhances fatty acid oxidation. Consequently, AMPK activation strongly suppresses lipid accumulation in the affected tissues.

Collectively, these observations indicate that Pin1 favors enhanced lipogenesis, functioning via at least three mechanisms; through an insulin-signaling-dependent association with IRS-1 and Akt, as well as exerting AMPK-dependent and direct actions on lipid enzymes such as ACC1 and FASN, as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The functions of Pin1 in the molecular mechanism of lipogenesis in adipocytes. Either an HFD or MCDD increases Pin1 expressions in the liver and adipocytes. In adipocytes and hepatocytes, Pin1 enhances lipogenesis through an insulin-signaling-dependent mechanism by associating with IRS-1 and Akt, exerting AMPK-dependent and direct actions on lipid enzymes such as ACC1 and FASN. In the energy consumption pathway, Pin1 downregulates the expressions of thermogenic genes, such as UCP-1, and reduces O2 consumption. Pin1 also enhances adipocyte differentiation by activating transcription of PPARγ protein in adipocytes. IRS-1: insulin receptor substrate 1. ACC: acetyl CoA carboxylase. PRDM16: PR domain containing 16. UCP-1: Uncoupling protein 1. PPARγ: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ.

Figure 1. The functions of Pin1 in the molecular mechanism of lipogenesis in adipocytes. Either an HFD or MCDD increases Pin1 expressions in the liver and adipocytes. In adipocytes and hepatocytes, Pin1 enhances lipogenesis through an insulin-signaling-dependent mechanism by associating with IRS-1 and Akt, exerting AMPK-dependent and direct actions on lipid enzymes such as ACC1 and FASN. In the energy consumption pathway, Pin1 downregulates the expressions of thermogenic genes, such as UCP-1, and reduces O2 consumption. Pin1 also enhances adipocyte differentiation by activating transcription of PPARγ protein in adipocytes. IRS-1: insulin receptor substrate 1. ACC: acetyl CoA carboxylase. PRDM16: PR domain containing 16. UCP-1: Uncoupling protein 1. PPARγ: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ.4. Essential Role of Adipose Pin1 in Obesity and NASH Development

Obesity is one of the risk factors for a fatty liver, though not all cases are obese. Recent reports have revealed that excessive lipid accumulation leads to adipocyte fibrosis [41]. Fibrotic adipocytes lose the ability to store triglycerides and ectopic fat accumulates in the affected livers. Accordingly, the amelioration of obesity rescues these livers from excessive fat storage.

Insulin resistance with hyperinsulinemia are known to further promote obesity. Pin1 controls glucose metabolism through insulin signaling, AMPK and transcription of the enzymes regulating gluconeogenesis [31]. Indeed, Pin1 null mice exhibit impairments of both glucose and insulin tolerance [42]. In addition, Pin1 is a key player in the release of insulin, as Pin1 deletion in islets alleviates insulin release in response to high glucose [43]. In contrast, adipocyte-specific Pin1 knockout (KO) mice have lower body weights, with liver triglyceride and macrophage infiltration of epididymal white adipose tissue when fed a HFD [30].

Interestingly, adipocyte-specific Pin1 KO mice show an alleviation of both HFD-induced obesity and fatty liver development, indicating the amelioration of obesity to be linked to the prevention of NASH. Pin1 enhances adipocyte differentiation by activating the transcription of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) protein in adipocytes without affecting PPARγ protein levels [44]. The study also revealed PPARγ expression levels to be upregulated during adipogenesis and that Pin1 knockdown impairs adipogenesis.

A recent investigation found that Pin1 is involved in the regulation of non-shivering thermogenesis in both brown and beige adipocytes. Pin1 interacts with the PR domain containing 16 (PRDM16), which is involved in the expression of the uncoupling protein (UCP-1), a major contributor to thermogenic programs. PRDM16, by associating with Pin1, is rapidly degraded through the ubiquitin–proteasome system, depending on the isomerase activity of Pin1. Indeed, Pin1 deletion in adipocytes elevates the expression of thermogenic genes and promotes O2 consumption [30].

Therefore, it has now become clear that not only hepatic but also adipose Pin1 is a major player in obesity development, contributing to the development of NAFLD or NASH, as shown in Figure 1.

5. Pin1 Promotes the Generation of ROS by Associating with NADPH Oxidase

Excessive free fatty acids (FFA) activate oxygen consumption in mitochondria. In the respiratory chain, which is activated in the presence of excessive FFA, complexes I and II are the main sources of mitochondrial ROS [45]. FFA present in excess also activates NADPH oxidase via protein kinase C (PKC) and produces ROS [46]. The NADPH oxidase (Nox) consists of six subcomponents (p47phox, p67phox, p40phox, Rac2, p22phox and gp91phox), in addition to Nox2 itself [47][48]. Although the mechanism of Nox2 activation is complex, it is essential that p47phox, phosphorylated by stimuli, be transferred to the membrane and then associate with p22phox.

Several studies have shown that Pin1 enhances superoxide production via NADPH oxidase activation [49][50]. The Toll-like receptor 7/8 (TLR7/8) agonists CL097 and TNF-α reportedly exert priming effects on N-Formylmethionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLF)-induced NADPH oxidase-mediated ROS production via p47phox translocation to the membranes. Pin1 binds to p47phox via phosphorylated Ser345 and then promotes p47phox translocation.

Increased ROS production in cells activates the NFE2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) and Forkhead box O (FoxO) pathways, functioning to both regulate and manage oxidative stress [51][52][53]. Nrf2 is a transcription factor also activated by phosphatidylinositol-5-phosphate (PtdIns5P), and is usually inactivated by binding to Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1) [51][54][55]. PtdIns5P levels are strictly regulated by phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate 4-kinase (PIP4K) [55]. Stimulation with ROS oxidizes KEAP1 and this modification results in dissociation between Nrf2 and KEAP1. Consequently, Nrf2 which is translocated to the nucleus accelerates the transcriptions of antioxidant genes, such as heme-oxygenase1 [51][56].

In the Nrf2 pathway, Pin1 inhibits Nrf2 and PIP4K, which synthesize PtdInsP2 (4, 5) and remove PtdIns5P by phosphorylating it. A study on vascular smooth muscle cells showed that Pin1 overexpression increases the ubiquitination of Nrf2 and inhibits its nuclear translocation [57]. Another study showed that Pin1 and PIP4K co-localize in nuclear speckles and block the actions of PtdIns5P, which is the only known activator of Nrf2, by phosphorylating it [58].

6. Pin1 Enhances Inflammation

Inflammation and fibrotic change contribute to progression from NAFLD to NASH. Expressions of inflammatory cytokines are largely regulated by the pathways of the two transcription factors, nuclear factor-kB (NF-kB) and activator protein 1 (AP-1) [45][46][49]. Pin1 enhances both of these transcriptional pathways, as described below.

The family of inducible transcription factors NF-κB/Rel impacts cell survival, inflammation and the process of tumorigenesis. [59][60]. There are five structurally related NF-κB family proteins, including p50, p52, RelA (p65), RelB and c-Rel [61]. NF-κB exists in heterodimer or homodimer forms and is usually localized in the cytoplasm via interactions with IκB family members [62]. The NF-κB pathway activation begins with the inducible degradation of IκBα due to site-specific phosphorylation by the multi-subunit IκB kinase complex [63]. The detachment of IκBα induces the nuclear translocation of RelA/p50 heterodimers and initiates the induction of various pro-inflammatory genes [64]. Activated p65 and P50 bound to DNA are inactivated upon moving to the cytoplasm in response to rebinding with IκB [65][66]. Ryo et al. reported that Pin1-specific binding of p65 to the pThr254-Pro motif inhibits p65 from binding to IκBα, thereby enhancing p65 nuclear localization. Moreover, Pin1 exerts effects on p65 protein stability, since Pin1 deficiency reduces p65 protein levels. Accordingly, Pin1 regulates NF-κB pathway activation by controlling both the translocation and the protein stability of p65 [67][68]. Another study also found that Pin1 interacts with c-Rel and thereby promotes both nuclear translocation and transforming activity [69].

In the AP-1 signaling pathway, AP-1 transcriptional activity is regulated by c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), a member of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) group [70]. JNK activity is upregulated by phosphorylation of Thr and Tyr residues and these phosphorylations are a response to a variety of stressors such as oxidative stress or inflammatory cytokines [71][72]. Pin1 activates this pathway by interacting with phosphorylated JNK1 [71]. The bindings of Pin1 and JNK1 induce the interaction of JNK1 to c-Jun and activating transcription factor 2 (ATF2), which are downstream members of the AP-1 family. Pin1 also activates the AP-1 signaling pathway via upregulation of p70S6K activity [73] (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The functions of Pin1 in the molecular mechanism underlying inflammation in hepatocytes. Pin1 enhances superoxide production via NADPH oxidase activation and increases ROS production. In the downstream portion of this pathway, Pin1 inhibits the ROS resistant pathway and induces hepatic inflammation. Pin1 also activates the NF-κB and JNK-AP-1 pathways, thereby inducing hepatic inflammation. ROS: reactive oxygen species. FFA: Free fatty acid. FoxO: Forkhead box O. Nrf2: NFE2-related factor 2. NF-kB: nuclear factor-kB.

Figure 2. The functions of Pin1 in the molecular mechanism underlying inflammation in hepatocytes. Pin1 enhances superoxide production via NADPH oxidase activation and increases ROS production. In the downstream portion of this pathway, Pin1 inhibits the ROS resistant pathway and induces hepatic inflammation. Pin1 also activates the NF-κB and JNK-AP-1 pathways, thereby inducing hepatic inflammation. ROS: reactive oxygen species. FFA: Free fatty acid. FoxO: Forkhead box O. Nrf2: NFE2-related factor 2. NF-kB: nuclear factor-kB.7. Pin1 Activates the Pathways Leading to Fibrosis

Yılmaz and colleagues raised the possibility that Pin1 concentrations in serum may well be exploited as markers for the detection of NASH and for determining advanced fibrotic scores for this disease [74]. The serum Pin1 levels were found to correlate with histopathological features in patients with NASH and to be independent predictors of advanced liver fibrosis. Furthermore, treatment with the Pin1 inhibitor juglone reportedly ameliorates drug-induced liver fibrosis [26]. The study that obtained this finding showed the Pin1 expressions in fibrotic livers to be upregulated, and that Pin1 regulates the expression of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)1, a fibrogenesis regulator, and the phosphorylation of Smad2/3, a key regulator of the fibrogenesis signaling pathway, in hepatic stellate cells (HSCs).

Numerous studies have confirmed the importance of the TGF-β-SMAD signaling pathway during the process of hepatic fibrosis. TGF-β is a ubiquitous factor which reportedly promotes fibrosis in various tissues [75][76]. TGF-β signaling occurs via both canonical Smad and non-Smad pathways [77]. TGF-β receptor I (TGF-βRI) phosphorylates the intracellular mediator receptor-regulated Smads (R-Smads), Smad2 and Smad3 [77][78][79]. Phosphorylated R-Smad is a dimer and the common mediator Smad (Co-Smad), also known as Smad4, is another member of the Smad family, and forms heterodimeric complexes in the cytosol [77][80]. The Smad complex accumulates in the nucleus and cooperates with other transcription factors to control gene transcription [77]. These Smad complex activities are negatively regulated by Smad6 and Smad7 which constitute a third class of Smad proteins, referred to as inhibitory Smad (I-Smad) [77].

Pin1 reportedly activates the TGF-Smad pathway and is thereby involved in fibrotic change [31][34][81][82]. The translational activity of TGF-β1 mRNA is regulated by various proteins. AU-rich element RNA-binding protein 1(AUF-1) binds to TGF-β1 mRNA and promotes its rapid exosome-mediated degradation [83]. Pin1 leads to the isomerization of hyper-phosphorylated AUF1 isoforms, and thereby reduces AUF1 binding to TGF-β1 mRNA and suppresses exosome-mediated mRNA decay [84]. Another study showed that Pin1 interacts with SUMOylated promyelocytic leukemia protein (PML), which acts as a nuclear translocation promoter and a TGFβ1 transcriptional regulator, increasing TGFβ1 mRNA expression and also, enhancing the TGFβ1-mediated Smad2/3 signaling pathway [85]. Pin1, as a part of the Smad pathway, interacts with both Smad2 and Smad3, thereby enhancing their phosphorylation and the resulting transcriptional activity [33][81][82].

In addition, Pin1-mediated isomerization of the inhibitory Smad6 MH2 domain may alter Smad6 functions such as nuclear localization signals and nuclear export signals. This isomerization increases phosphorylation, nuclear localization, and gene activation of Smad3 in response to TGFβ1 treatments and activates the TGF-β-Smad signaling pathway [86]. Several prior studies have confirmed that Pin1 knockdown or treatment with Pin1 inhibitors suppresses Smad phosphorylation and the expressions of fibrotic genes induced by the TGF-Smad pathway [31][82].

Signal transducers and activators of transcription (STATs) family pathways are also important for cytokine signaling and effects [87]. Leptin and IL-6 activate the STAT3 signaling pathway and increase HSC collagen mRNA expression [88]. Recent studies have shown that the complex of STAT3 and JunB can directly control activation of the COL1A2 enhancer [89][90]. In addition, STAT3 activates the TGF-Smad pathway. A study of dermal fibroblasts showed that activation of STAT3 by IL-6 results in TGFβ activation [91].

Stat3 transcriptional activity is regulated by Tyr-phosphorylation followed by dimerization and translocation from the cytosol to the nucleus. A breast cancer cell study demonstrated that Pin1 enhances STAT3 transcriptional activity by interacting with Ser727-phosphorylated STAT3 [92]. This entry also revealed that Pin1 promotes STAT3-mediated epithelial–mesenchymal transition, thereby inducing liver fibrosis.

These studies showed Pin1 to be a key regulator of fibrosis and to have potential as a pharmacologic target for treating liver fibrosis, as seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3. The functions of Pin1 in the molecular mechanism underlying fibrosis in HSCs. Pin1 activates TGF-β mRNA translation activity and the SMAD pathway in HSCs, which in turn activates extracellular matrix Col-1 and αSMA protein expression.

Figure 3. The functions of Pin1 in the molecular mechanism underlying fibrosis in HSCs. Pin1 activates TGF-β mRNA translation activity and the SMAD pathway in HSCs, which in turn activates extracellular matrix Col-1 and αSMA protein expression.References

- Hashimoto, E.; Tokushige, K. Prevalence, gender, ethnic variations, and prognosis of NASH. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 46, 63–69.

- Sherif, Z.A.; Saeed, A.; Ghavimi, S.; Nouraie, S.M.; Laiyemo, A.O.; Brim, H.; Ashktorab, H. Global Epidemiology of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Perspectives on US Minority Populations. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2016, 61, 1214–1225.

- Vernon, G.; Baranova, A.; Younossi, Z.M. Systematic review: The epidemiology and natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in adults. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 34, 274–285.

- Brunt, E.M.; Kleiner, D.E.; Wilson, L.A.; Belt, P.; Neuschwander-Tetri, B.A.; NASH Clinical Research Network (CRN). Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) activity score and the histopathologic diagnosis in NAFLD: Distinct clinicopathologic meanings. Hepatology 2011, 53, 810–820.

- Younossi, Z.M.; Koenig, A.B.; Abdelatif, D.; Fazel, Y.; Henry, L.; Wymer, M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology 2016, 64, 73–84.

- Zelber-Sagi, S.; Nitzan-Kaluski, D.; Halpern, Z.; Oren, R. Prevalence of primary non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in a population-based study and its association with biochemical and anthropometric measures. Liver Int. 2006, 26, 856–863.

- Wang, R.T.; Koretz, R.L.; Yee Jr, H.F. Is weight reduction an effective therapy for nonalcoholic fatty liver? A systematic review. Am. J. Med. 2003, 115, 554–559.

- Promrat, K.; Kleiner, D.E.; Niemeier, H.M.; Jackvony, E.; Kearns, M.; Wands, J.R.; Fava, J.L.; Wing, R.R. Randomized controlled trial testing the effects of weight loss on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2010, 51, 121–129.

- Hamaguchi, M.; Kojima, T.; Takeda, N.; Nakagawa, T.; Taniguchi, H.; Fujii, K.; Omatsu, T.; Nakajima, T.; Sarui, H.; Shimazaki, M.; et al. The metabolic syndrome as a predictor of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 2005, 143, 722–728.

- Marchesini, G.; Brizi, M.; Morselli-Labate, A.M.; Bianchi, G.; Bugianesi, E.; McCullough, A.J.; Forlani, G.; Melchionda, N. Association of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with insulin resistance. Am. J. Med. 1999, 107, 450–455.

- Chen, C.H.; Huang, M.H.; Yang, J.C.; Nien, C.; Yang, C.C.; Yeh, Y.H.; Yueh, S.K. Prevalence and risk factors of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in an adult population of taiwan: Metabolic significance of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in nonobese adults. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2006, 40, 745–752.

- Wang, Z.; Xia, B.; Ma, C.; Hu, Z.; Chen, X.; Cao, P. Prevalence and risk factors of fatty liver disease in the Shuiguohu district of Wuhan city, central China. Postgrad. Med. J. 2007, 83, 192–195.

- Fan, J.G.; Li, F.; Cai, X.B.; Peng, Y.D.; Ao, Q.H.; Gao, Y. The importance of metabolic factors for the increasing prevalence of fatty liver in Shanghai factory workers. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2007, 22, 663–668.

- Malik, S.M.; deVera, M.E.; Fontes, P.; Shaikh, O.; Ahmad, J. Outcome after liver transplantation for NASH cirrhosis. Am. J. Transplant. 2009, 9, 782–793.

- Chen, Y.; Wu, Y.R.; Yang, H.Y.; Li, X.Z.; Jie, M.M.; Hu, C.J.; Wu, Y.Y.; Yang, S.M.; Yang, Y.B. Prolyl isomerase Pin1: A promoter of cancer and a target for therapy. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 883.

- Pearson, G.; Robinson, F.; Beers Gibson, T.; Xu, B.E.; Karandikar, M.; Berman, K.; Cobb, M.H. Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways: Regulation and physiological functions. Endocr. Rev. 2001, 22, 153–183.

- Morgan, D.O. Cyclin-dependent kinases: Engines, clocks, and microprocessors. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 1997, 13, 261–291.

- Lu, K.P.; Liou, Y.C.; Zhou, X.Z. Pinning down proline-directed phosphorylation signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 2002, 12, 164–172.

- Schmidpeter, P.A.; Koch, J.R.; Schmid, F.X. Control of protein function by prolyl isomerization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1850, 1973–1982.

- Schmid, F.X. Prolyl isomerase: Enzymatic catalysis of slow protein-folding reactions. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 1993, 22, 123–142.

- Day, C.P.; Saksena, S. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: Definitions and pathogenesis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2002, 17, S377–S384.

- Yeh, E.S.; Means, A.R. PIN1, the cell cycle and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2007, 7, 381–388.

- Verdecia, M.A.; Bowman, M.E.; Lu, K.P.; Hunter, T.; Noel, J.P. Structural basis for phosphoserine-proline recognition by group IV WW domains. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2000, 7, 639–643.

- Matena, A.; Rehic, E.; Hönig, D.; Kamba, B.; Bayer, P. Structure and function of the human parvulins Pin1 and Par14/17. Biol. Chem. 2018, 399, 101–125.

- Kuboki, S.; Sakai, N.; Clarke, C.; Schuster, R.; Blanchard, J.; Edwards, M.J.; Lentsch, A.B. The peptidyl-prolyl isomerase, Pin1, facilitates NF-kappaB binding in hepatocytes and protects against hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury. J. Hepatol. 2009, 51, 296–306.

- Yang, J.W.; Hien, T.T.; Lim, S.C.; Jun, D.W.; Choi, H.S.; Yoon, J.H.; Cho, I.J.; Kang, K.W. Pin1 induction in the fibrotic liver and its roles in TGF-β1 expression and Smad2/3 phosphorylation. J. Hepatol. 2014, 60, 1235–1241.

- Wulf, G.M.; Ryo, A.; Wulf, G.G.; Lee, S.W.; Niu, T.; Petkova, V.; Lu, K.P. Pin1 is overexpressed in breast cancer and cooperates with Ras signaling in increasing the transcriptional activity of c-Jun towards cyclin D1. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 3459–3472.

- Rustighi, A.; Tiberi, L.; Soldano, A.; Napoli, M.; Nuciforo, P.; Rosato, A.; Kaplan, F.; Capobianco, A.; Pece, S.; Di Fiore, P.P.; et al. The prolyl-isomerase Pin1 is a Notch1 target that enhances Notch1 activation in cancer. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009, 11, 133–142.

- Day, C.P.; James, O.F. Steatohepatitis: A tale of two “hits”? Gastroenterology 1998, 114, 842–845.

- Nakatsu, Y.; Matsunaga, Y.; Yamamotoya, T.; Ueda, K.; Inoue, M.K.; Mizuno, Y.; Nakanishi, M.; Sano, T.; Yamawaki, Y.; Kushiyama, A.; et al. Prolyl Isomerase Pin1 Suppresses Thermogenic Programs in Adipocytes by Promoting Degradation of Transcriptional Co-activator PRDM16. Cell Rep. 2019, 26, 3221.e3–3230.e3.

- Nakatsu, Y.; Matsunaga, Y.; Yamamotoya, T.; Ueda, K.; Inoue, Y.; Mori, K.; Sakoda, H.; Fujishiro, M.; Ono, H.; Kushiyama, A.; et al. Physiological and Pathogenic Roles of Prolyl Isomerase Pin1 in Metabolic Regulations via Multiple Signal Transduction Pathway Modulations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1495.

- Rosen, E.D.; MacDougald, O.A. Adipocyte differentiation from the inside out. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006, 7, 885–896.

- Liao, Y.; Wei, Y.; Zhou, X.; Yang, J.Y.; Dai, C.; Chen, Y.J.; Agarwal, N.K.; Sarbassov, D.; Shi, D.; Yu, D.; et al. Peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase Pin1 is critical for the regulation of PKB/Akt stability and activation phosphorylation. Oncogene 2009, 28, 2436–2445.

- Ueda, K.; Nakatsu, Y.; Yamamotoya, T.; Ono, H.; Inoue, Y.; Inoue, M.K.; Mizuno, Y.; Matsunaga, Y.; Kushiyama, A.; Sakoda, H.; et al. Prolyl isomerase Pin1 binds to and stabilizes acetyl CoA carboxylase 1 protein, thereby supporting cancer cell proliferation. Oncotarget 2019, 10, 1637–1648.

- Yun, H.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, G.; Choi, H.S. Prolyl-isomerase Pin1 impairs trastuzumab sensitivity by up-regulating fatty acid synthase expression. Anticancer Res. 2014, 34, 1409–1416.

- Nakatsu, Y.; Iwashita, M.; Sakoda, H.; Ono, H.; Nagata, K.; Matsunaga, Y.; Fukushima, T.; Fujishiro, M.; Kushiyama, A.; Kamata, H.; et al. Prolyl isomerase Pin1 negatively regulates AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) by associating with the CBS domain in the γ subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 24255–24266.

- Ronnett, G.V.; Kleman, A.M.; Kim, E.K.; Landree, L.E.; Tu, Y. Fatty acid metabolism, the central nervous system, and feeding. Obesity 2006, 14, 201S–207S.

- Hardie, D.G.; Pan, D.A. Regulation of fatty acid synthesis and oxidation by the AMP-activated protein kinase. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2002, 30, 1064–1070.

- Hardie, D.G.; Carling, D. The AMP-activated protein kinase—fuel gauge of the mammalian cell? Eur. J. Biochem. 1997, 246, 259–273.

- Ruderman, N.B.; Saha, A.K.; Kraegen, E.W. Minireview: Malonyl CoA, AMP-activated protein kinase, and adiposity. Endocrinology 2003, 144, 5166–5171.

- Reggio, S.; Pellegrinelli, V.; Clément, K.; Tordjman, J. Fibrosis as a Cause or a Consequence of White Adipose Tissue Inflammation in Obesity. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2013, 2, 1–9.

- Nakatsu, Y.; Sakoda, H.; Kushiyama, A.; Zhang, J.; Ono, H.; Fujishiro, M.; Kikuchi, T.; Fukushima, T.; Yoneda, M.; Ohno, H.; et al. Peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase NIMA-interacting 1 associates with insulin receptor substrate-1 and enhances insulin actions and adipogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 20812–20822.

- Nakatsu, Y.; Mori, K.; Matsunaga, Y.; Yamamotoya, T.; Ueda, K.; Inoue, Y.; Mitsuzaki-Miyoshi, K.; Sakoda, H.; Fujishiro, M.; Yamaguchi, S.; et al. The prolyl isomerase Pin1 increases β-cell proliferation and enhances insulin secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 11886–11895.

- Han, Y.; Lee, S.H.; Bahn, M.; Yeo, C.Y.; Lee, K.Y. Pin1 enhances adipocyte differentiation by positively regulating the transcriptional activity of PPARγ. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2016, 436, 150–158.

- Dikalov, S. Cross talk between mitochondria and NADPH oxidases. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 51, 1289–1301.

- Roberts, A.C.; Porter, K.E. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction in diabetes. Diabetes Vasc. Dis. Res. 2013, 10, 472–482.

- Belambri, S.A.; Rolas, L.; Raad, H.; Hurtado-Nedelec, M.; Dang, P.M.; El-Benna, J. NADPH oxidase activation in neutrophils: Role of the phosphorylation of its subunits. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 48, e12951.

- Groemping, Y.; Rittinger, K. Activation and assembly of the NADPH oxidase: A structural perspective. Biochem. J. 2005, 386, 401–416.

- Makni-Maalej, K.; Boussetta, T.; Hurtado-Nedelec, M.; Belambri, S.A.; Gougerot-Pocidalo, M.A.; El-Benna, J. The TLR7/8 agonist CL097 primes N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine-stimulated NADPH oxidase activation in human neutrophils: Critical role of p47phox phosphorylation and the proline isomerase Pin1. J. Immunol. 2012, 189, 4657–4665.

- Boussetta, T.; Gougerot-Pocidalo, M.A.; Hayem, G.; Ciappelloni, S.; Raad, H.; Arabi Derkawi, R.; Bournier, O.; Kroviarski, Y.; Zhou, X.Z.; Malter, J.S.; et al. The prolyl isomerase Pin1 acts as a novel molecular switch for TNF-alpha-induced priming of the NADPH oxidase in human neutrophils. Blood 2010, 116, 5795–5802.

- Keune, W.J.; Jones, D.R.; Divecha, N. PtdIns5P and Pin1 in oxidative stress signaling. Adv. Biol. Regul. 2013, 53, 179–189.

- DeNicola, G.M.; Karreth, F.A.; Humpton, T.J.; Gopinathan, A.; Wei, C.; Frese, K.; Mangal, D.; Yu, K.H.; Yeo, C.J.; Calhoun, E.S.; et al. Oncogene-induced Nrf2 transcription promotes ROS detoxification and tumorigenesis. Nature 2011, 475, 106–109.

- Tothova, Z.; Kollipara, R.; Huntly, B.J.; Lee, B.H.; Castrillon, D.H.; Cullen, D.E.; McDowell, E.P.; Lazo-Kallanian, S.; Williams, I.R.; Sears, C.; et al. FoxOs are critical mediators of hematopoietic stem cell resistance to physiologic oxidative stress. Cell 2007, 128, 325–339.

- McMahon, M.; Itoh, K.; Yamamoto, M.; Hayes, J.D. Keap1-dependent proteasomal degradation of transcription factor Nrf2 contributes to the negative regulation of antioxidant response element-driven gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 21592–21600.

- Kobayashi, A.; Kang, M.I.; Okawa, H.; Ohtsuji, M.; Zenke, Y.; Chiba, T.; Igarashi, K.; Yamamoto, M. Oxidative stress sensor Keap1 functions as an adaptor for Cul3-based E3 ligase to regulate proteasomal degradation of Nrf2. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004, 24, 7130–7139.

- Hayes, J.D.; McMahon, M.; Chowdhry, S.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T. Cancer chemoprevention mechanisms mediated through the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2010, 13, 1713–1748.

- Kim, S.E.; Lee, M.Y.; Lim, S.C.; Hien, T.T.; Kim, J.W.; Ahn, S.G.; Yoon, J.H.; Kim, S.K.; Choi, H.S.; Kang, K.W. Role of Pin1 in neointima formation: Down-regulation of Nrf2-dependent heme oxygenase-1 expression by Pin1. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 48, 1644–1653.

- Keune, W.J.; Jones, D.R.; Bultsma, Y.; Sommer, L.; Zhou, X.Z.; Lu, K.P.; Divecha, N. Regulation of phosphatidylinositol-5-phosphate signaling by Pin1 determines sensitivity to oxidative stress. Sci. Signal. 2012, 5, ra86.

- Liu, T.; Zhang, L.; Joo, D.; Sun, S.C. NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2017, 2, 17023.

- Oeckinghaus, A.; Ghosh, S. The NF-kappaB family of transcription factors and its regulation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2009, 1, a000034.

- Sun, S.C.; Chang, J.H.; Jin, J. Regulation of nuclear factor-κB in autoimmunity. Trends Immunol. 2013, 34, 282–289.

- Sun, S.C. Non-canonical NF-κB signaling pathway. Cell Res. 2011, 21, 71–85.

- Karin, M.; Delhase, M. The I kappa B kinase (IKK) and NF-kappa B: Key elements of proinflammatory signalling. Semin. Immunol. 2000, 12, 85–98.

- Karin, M.; Ben-Neriah, Y. Phosphorylation meets ubiquitination: The control of NF-B activity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2000, 18, 621–663.

- Li, Q.; Verma, I.M. NF-kappaB regulation in the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002, 2, 725–734.

- Ghosh, S.; Karin, M. Missing pieces in the NF-kappaB puzzle. Cell 2002, 109, S81–S96.

- Ryo, A.; Suizu, F.; Yoshida, Y.; Perrem, K.; Liou, Y.C.; Wulf, G.; Rottapel, R.; Yamaoka, S.; Lu, K.P. Regulation of NF-kappaB signaling by Pin1-dependent prolyl isomerization and ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis of p65/RelA. Mol. Cell 2003, 12, 1413–1426.

- Takino, J.; Nagamine, K.; Hori, T.; Sakasai-Sakai, A.; Takeuchi, M. Contribution of the toxic advanced glycation end-products-receptor axis in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis-related hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Hepatol. 2015, 7, 2459–2469.

- Yang, M.C.; Wang, C.J.; Liao, P.C.; Yen, C.J.; Shan, Y.S. Hepatic stellate cells secretes type I collagen to trigger epithelial mesenchymal transition of hepatoma cells. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2014, 4, 751–763.

- Davis, R.J. Signal transduction by the JNK group of MAP kinases. Cell 2000, 103, 239–252.

- Park, J.E.; Lee, J.A.; Park, S.G.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, H.J.; Uchida, C.; Uchida, T.; Park, B.C.; Cho, S. A critical step for JNK activation: Isomerization by the prolyl isomerase Pin1. Cell Death Differ. 2012, 19, 153–161.

- Kyriakis, J.M.; Avruch, J. Mammalian mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways activated by stress and inflammation. Physiol. Rev. 2001, 81, 807–869.

- Fan, G.; Fan, Y.; Gupta, N.; Matsuura, I.; Liu, F.; Zhou, X.Z.; Lu, K.P.; Gélinas, C. Peptidyl-prolyl isomerase Pin1 markedly enhances the oncogenic activity of the rel proteins in the nuclear factor-kappaB family. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 4589–4597.

- Cengiz, M.; Ozenirler, S.; Yücel, A.A.; Yılmaz, G. Can serum pin1 level be regarded as an indicative marker of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and fibrotic stages? Digestion 2014, 90, 35–41.

- Arjaans, M.; Munnink, T.H.O.; Timmer-Bosscha, H.; Reiss, M.; Walenkamp, A.M.; Lub-de Hooge, M.N.; de Vries, E.G.; Schröder, C.P. Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β expression and activation mechanisms as potential targets for anti-tumor therapy and tumor imaging. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 135, 123–132.

- Tucker, G.C. Integrins: Molecular targets in cancer therapy. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2006, 8, 96–103.

- Ross, S.; Hill, C.S. How the Smads regulate transcription. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2008, 40, 383–408.

- Graff, J.M.; Bansal, A.; Melton, D.A. Xenopus Mad proteins transduce distinct subsets of signals for the TGF beta superfamily. Cell 1996, 85, 479–487.

- Zhang, Y.; Feng, X.; We, R.; Derynck, R. Receptor-associated Mad homologues synergize as effectors of the TGF-beta response. Nature 1996, 383, 168–172.

- Lagna, G.; Hata, A.; Hemmati-Brivanlou, A.; Massagué, J. Partnership between DPC4 and SMAD proteins in TGF-beta signalling pathways. Nature 1996, 383, 832–836.

- Matsuura, I.; Chiang, K.N.; Lai, C.Y.; He, D.; Wang, G.; Ramkumar, R.; Uchida, T.; Ryo, A.; Lu, K.; Liu, F. Pin1 promotes transforming growth factor-beta-induced migration and invasion. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 1754–1764.

- Aragón, E.; Goerner, N.; Zaromytidou, A.I.; Xi, Q.; Escobedo, A.; Massagué, J.; Macias, M.J. A Smad action turnover switch operated by WW domain readers of a phosphoserine code. Genes Dev. 2011, 25, 1275–1288.

- Atkinson, G.P.; Nozell, S.E.; Harrison, D.K.; Stonecypher, M.S.; Chen, D.; Benveniste, E.N. The prolyl isomerase Pin1 regulates the NF-kappaB signaling pathway and interleukin-8 expression in glioblastoma. Oncogene 2009, 28, 3735–3745.

- Shen, Z.J.; Esnault, S.; Malter, J.S. The peptidyl-prolyl isomerase Pin1 regulates the stability of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor mRNA in activated eosinophils. Nat. Immunol. 2005, 6, 1280–1287.

- Wu, D.; Huang, D.; Li, L.L.; Ni, P.; Li, X.X.; Wang, B.; Han, Y.N.; Shao, X.Q.; Zhao, D.; Chu, W.F.; et al. TGF-β1-PML SUMOylation-peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase NIMA-interacting 1 (Pin1) form a positive feedback loop to regulate cardiac fibrosis. J. Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 6263–6273.

- Shen, Z.J.; Braun, R.K.; Hu, J.; Xie, Q.; Chu, H.; Love, R.B.; Stodola, L.A.; Rosenthal, L.A.; Szakaly, R.J.; Sorkness, R.L.; et al. Pin1 protein regulates Smad protein signaling and pulmonary fibrosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 23294–23305.

- Xu, M.Y.; Hu, J.J.; Shen, J.; Wang, M.L.; Zhang, Q.Q.; Qu, Y.; Lu, L.G. Stat3 signaling activation crosslinking of TGF-β1 in hepatic stellate cell exacerbates liver injury and fibrosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1842, 2237–2245.

- Saxena, N.K.; Ikeda, K.; Rockey, D.C.; Friedman, S.L.; Anania, F.A. Leptin in hepatic fibrosis: Evidence for increased collagen production in stellate cells and lean littermates of ob/ob mice. Hepatology 2002, 35, 762–771.

- Papaioannou, I.; Xu, S.; Denton, C.P.; Abraham, D.J.; Ponticos, M. STAT3 controls COL1A2 enhancer activation cooperatively with JunB, regulates type I collagen synthesis posttranscriptionally, and is essential for lung myofibroblast differentiation. Mol. Biol. Cell 2018, 29, 84–95.

- Kasembeli, M.M.; Bharadwaj, U.; Robinson, P.; Tweardy, D.J. Contribution of STAT3 to Inflammatory and Fibrotic Diseases and Prospects for its Targeting for Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2299.

- O’Reilly, S.; Ciechomska, M.; Cant, R.; van Laar, J.M. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) trans signaling drives a STAT3-dependent pathway that leads to hyperactive transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling promoting SMAD3 activation and fibrosis via Gremlin protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 9952–9960.

- Lufei, C.; Koh, T.H.; Uchida, T.; Cao, X. Pin1 is required for the Ser727 phosphorylation-dependent Stat3 activity. Oncogene 2007, 26, 7656–7664.

More

Information

Subjects:

Cell Biology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

956

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

07 Apr 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No