Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sebastian Ulrich | -- | 3098 | 2022-04-04 14:32:53 | | | |

| 2 | Beatrix Zheng | + 304 word(s) | 3402 | 2022-04-06 04:41:12 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Ulrich, S.; , .; Baschien, C.; Kosicki, R.; Twarużek, M.; Straubinger, R.; Ebel, F. Possible Evolution of the Genotypes of Stachybotrys chartarum. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21352 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Ulrich S, , Baschien C, Kosicki R, Twarużek M, Straubinger R, et al. Possible Evolution of the Genotypes of Stachybotrys chartarum. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21352. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Ulrich, Sebastian, , Christiane Baschien, Robert Kosicki, Magdalena Twarużek, Reinhard Straubinger, Frank Ebel. "Possible Evolution of the Genotypes of Stachybotrys chartarum" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21352 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Ulrich, S., , ., Baschien, C., Kosicki, R., Twarużek, M., Straubinger, R., & Ebel, F. (2022, April 04). Possible Evolution of the Genotypes of Stachybotrys chartarum. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/21352

Ulrich, Sebastian, et al. "Possible Evolution of the Genotypes of Stachybotrys chartarum." Encyclopedia. Web. 04 April, 2022.

Copy Citation

Stachybotrys chartarum is frequently isolated from damp building materials or improperly stored animal forage. Human and animal exposure to the secondary metabolites of this mold is linked to severe health effects. The mutually exclusive production of either satratoxins or atranones defines the chemotypes A and S. Based upon the genes (satratoxin cluster, SC1-3, sat or atranone cluster, AC1, atr) that are supposed to be essential for satratoxin and atranone production, S. chartarum can furthermore be divided into three genotypes: the S-type possessing all sat- but no atr-genes, the A-type lacking the sat- but harboring all atr-genes, and the H-type having only certain sat- and all atr-genes.

Stachybotrys

genome

macrocyclic trichothecene

atranone

1. Introduction

The family of Stachybotriaceae has been described as genetically hyperdiverse and heterogeneous concerning the different secondary metabolite classes they produce (e.g., atranones, phenylspirodrimanes, and trichothecenes) [1][2]. According to the MycoBank database [3][4], the genus Stachybotrys currently consists of 126 species. Up to now, only two of them (S. chartarum and S. chlorohalonata) are frequently isolated and have been associated with illnesses affecting humans and animals [1][5][6]. S. chartarum occurs ubiquitously and is frequently found on dead plants (e.g., straw) and other cellulosic (e.g., culinary herbs) and building materials (e.g., gypsum and wallpaper) [2][7][8][9]. S. chartarum is either subdivided into two distinct chemotypes (A and S) based on their production of either atranones (chemotype A) or macrocyclic trichothecenes (MT; chemotype S) [10] or into the genotypes A, S, and H according to the presence or absence of genes that are presumed to encode the relevant enzymes for the biosynthesis of these mycotoxins (atr1-14 and sat1-21) [11]. The highly cytotoxic chemotype S was found to produce MT, whereas cultures of the low-cytotoxic chemotype A produce atranones [10][12][13][14]. MT represent the most cell-toxic trichothecenes currently known and include roridin, verrucarin, and satratoxins [15].

By binding irreversibly to the 60S ribosomal subunit, satratoxins inhibit protein biosynthesis and can induce apoptosis in neuronal cell lines [16][17][18][19]. The genotype S has been implicated in several types of diseases [20][21][22][23][24][25][26]: in animals, stachybotryotoxicosis can occur after oral uptake of mycotoxins, especially in horses and less frequently in cattle and sheep [27][28][29]. Humans, especially infants, are primarily at risk after exposure to toxins in water-damaged buildings [20][30]. Exposure to MT may cause pulmonary hemorrhage in infants or symptoms related to the sick building syndrome complex [20][31][32]. Data on the biological activity of atranones are still scarce, but the available information suggest that they are less cytotoxic than MT [5]. Rand et al. [33] showed that relatively high concentrations of atranone A and C (2.0–20 μg/animal) can cause an inflammatory response in mice, but clinical case reports for humans have not been published yet. Semeiks et al. [34] described the satratoxin cluster 1–3 (SC 1–3) harboring the sat genes 1 to 21 to be essential for satratoxin production and the atranone core cluster (CAC or AC1) that contains the atr genes (atr1–14) and may suffice for the production of atranones. The AC2 was described as a second atranone-specific gene cluster, but Semeiks et al. [34] already noted that three of the six genes are also conserved in genotype S strains. The function of this gene cluster is still unclear.

Based upon recent genetic information, three genotypes of the fungus have been introduced: genotype A produces atranones but no satratoxins and possesses atr but no sat genes; genotype H (hybrid) produces no satratoxins and has a truncated cluster of sat genes and all atr genes; and genotype S produces satratoxins and has the complete set of sat genes but no atr genes [5]. Remarkably, no S. chartarum strains have been isolated to date that lack the atr and the sat genes. The three genotypes have common but also distinct features, and their evolutionary relationship is unknown. Currently, genomes of two satratoxin-producing strains (IBT 40293 and 7711) but only one genotype A strain (IBT 40288) are available in the NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) database (ASM102136v1 - GCA_001021365.1 - strain 51-11, S40293v1 - GCA_000732565.1 - strain IBT 40293, S7711v1 - GCA_000730325.1 - strain IBT 7711). The fourth S. chartarum genome that is available belongs to strain 51-11, for which no conclusive information exists so far concerning its chemotype. Up to now, no genome is available for a genotype H strain. Any analysis of the S. chartarum genomes is hampered by the fact that they are not fully assembled. Only sets of genomic scaffolds are deposited in the database and gene annotations are available only for three of the four genomes (IBT 7711, IBT 40293, and IBT 40288).

2. Current Insights

Mycotoxins are produced by distinct and elaborated biosynthetic pathways that have often been elucidated in only one species [35]. The class of trichothecenes is particular variable in its chemical structure and has therefore been divided, based on functional groups, in the types A to D [18]. MTs are also known as type D trichothecenes; they are complex molecules with particularly high toxicity compared to the simpler trichothecenes of the types A to C [18].

Certain MTs are also produced by different fungi other than S. chartarum, but within the species, they are exclusively produced by genotype S strains. Atranones belong to a different mycotoxin class and are generated by genotype A strains of S. chartarum as well as other Stachybotrys species, e.g., S. chlorohalonata. Currently, S. chartarum is not included in the MIBiG (Minimum Information about Biosynthetic Gene cluster) [36] since a functional validation for the SC and AC gene clusters is still pending. MTs are the putative end products of the trichothecene biosynthesis pathway that is still elusive, but several possible mechanisms have been proposed in the literature [18][34][37].

Biosynthetic gene clusters are highly variable, rapidly evolving, and often found on accessory chromosomes or at the ends of chromosomes [38][39][40]. The available genomes of S. chartarum are not fully annotated and exist as sets of genomic scaffolds. Hence, the researchers know the precise position of an AC or SC within the respective scaffold but not on the corresponding chromosome. Most of these clusters are apparently not residing at the very end of a chromosome. This is less clear for AC1, for which only a short downstream sequence is present in the database.

The genome of S. chartarum 51-11 comprises the most continuous sequences and thereby provides a framework to search for connections between individual scaffolds in the other S. chartarum genomes. Horizontal gene transfer may be involved in the evolution of the different S. chartarum genotypes, and this can result in a divergent G+C content [41]. The researchers therefore analyzed the G+C content of the gene clusters and the flanking regions of the respective scaffolds. All gene clusters have a similar G+C content as the rest of the genome, suggesting that they originate from Stachybotrys or a fungus with similar G+C content.

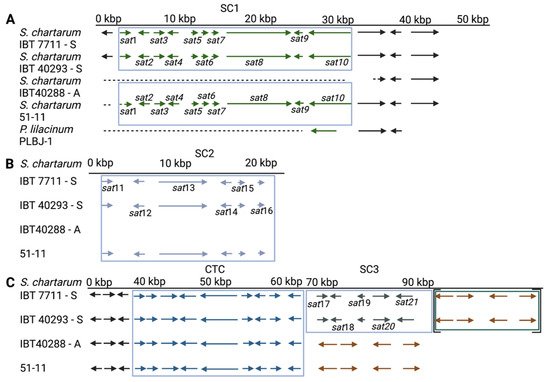

The genotype S is defined by the presence of the SC1-3 and the absence of the AC1 [34], criteria which are met by IBT 40293 and IBT 7711. No annotation is available for the genome sequence of strain 51-11. In this research, the researchers have identified an SC1 and SC2 but no AC1 or SC3; hence, 51-11 does not fully match the criteria of a genotype S strain, and the researchers therefore refer to it as an atypical S-type strain. The analysis of the flanking regions of the SC1-3 clusters indicates that their chromosomal positions are identical or at least very similar in the three S-type strains, which corroborates preliminary findings [11]. From these data, it appears unlikely that the SCs are very mobile genetic elements in the S. chartarum genome.

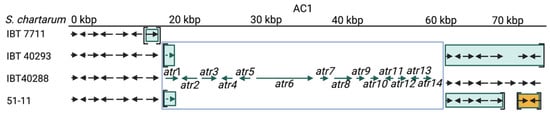

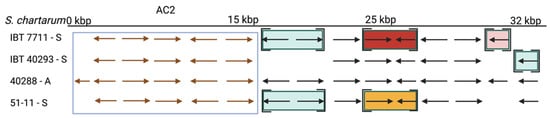

The situation is different for the AC. The AC1 cluster is present in the A-type strain IBT 40288 and H-type but not in S-type strains [11][34]. AC2 is not an A-type-specific region since it is present in all A- and S-type genomes analyzed in this research. According to the data, it is unlikely that the AC2-encoded proteins are directly involved in the production of atranones. No information is currently available on the presence and position of AC2 in H-type strains. In the A- and S-type genomes, AC2 resides in different positions, indicating that these clusters were acquired in several distinct events or that the respective regions underwent substantial genomic rearrangements.

A central question arising from the different genotypes of S. chartarum is their evolutionary relationship. The researchers have obtained several hints that shed light on the relations of the different genotypes and encouraged the researchers to develop a model that is consistent with the findings.

For unknown reasons, all S. chartarum strains the researchers know of possess either an AC1 and/or specific satratoxin gene clusters. This is true for the A- and S-type but also for H-type strains [11]. In a study comprising 105 S. chartarum strains, none possessed or lacked both the AC1 and the SC2 [42]. This strongly suggests that AC1 and SC2 are mutually exclusive. It is remarkable in this context that the researchers have no evidence that S. chartarum strains exist in which an intact SC2 coexists with an incomplete AC1 or vice versa. This finding is striking and suggests that acquisition of either of these gene clusters always entails a complete excision of the other. Although the precise pathway for the biosynthesis of MTs or atranones is unknown, the researchers know that farnesylpyrophosphate is the starting compound for both processes [14][18]. It appears that each strain has to choose whether it converts farnesylpyrophosphate into the direction of atranones or satratoxins. This is also supported by the genome of strain 51-11. Unfortunately, this strain is currently unavailable for culturing and MT analysis. The published data on the toxicity of 51-11 provide only hints but no concrete information on its MT production [43]. Thus, it is unclear whether strain 51-11 is a typical chemotype S strain. It would be interesting to know whether this strain produces and releases satratoxins even though the supposed MFS transporter (encoded in the SC3) is missing. Strain 51-11 differs from the other S-type strains since it lacks not only the SC3 cluster but also most of the sat1 gene of the SC1. This apparent loss of genetic information indicates that 55-11 developed from a typical S-type strain (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Current model of the evolution of the S. chartarum genotypes S, A, and H. The different gene clusters are depicted as boxes. The size and the position of these boxes do not represent the correct size and position of the respective cluster in the genome. Satratoxin gene clusters are shown in red and atranone gene clusters in blue.

If AC1 and SC2 are mutually exclusive, it is conceivable that an ancestor harbored one of these clusters, but the question remains: which one was first? The genotype H may provide clues for a better understanding of the evolutionary processes that shaped the current genotypes since it combines elements present in A- or S-type strains. According to the hypothesis of Semeiks et al. [34], the SC2 developed from a duplication of the CTC, which suggests that the S-type emerged from an A- or H-type ancestor. The fact that the researchers found truncated atr1 sequences in all S-type strains strengthens this hypothesis. It is, in principle, possible that the duplication of the CTC took place in an ancestral strain that contained only the CTC cluster, but such a strain has not been identified yet. Following the duplication of the CTC, a functional divergence may have resulted in the emergence of the SC2 and the parallel loss of the AC1. In this context, it is remarkable that BlastP searches identified a gene cluster in Monosporascus species, which encodes proteins that are homologous to specific SC2-encoded proteins but also trichodiensynthases that are homologous to proteins, which are encoded in the CTC of S. chartarum. Since Monosporascus is an important spoilage agent in melons [44] and was recently presumed to produce MT (roridin E) [45], this finding may also be relevant with respect to potential adverse health effects to humans.

The researchers' analyses also showed that the region located immediately downstream of the SC1 is particularly interesting. It is striking that the SC1-down-1 gene is well conserved in all S-type strains but truncated in the A-type strain and that the lost part of the gene would be most proximal to the SC1. The researchers assume that the SC1-down-1 gene was destroyed by an imprecise excision of the SC1, which implies that the A-type developed from a strain harboring the SC1, hence an H- or S-type strain.

The A-type strain IBT 40288 possesses a complete AC1 cluster, and the researchers' previously published PCR data suggest the same for all H-type strains analyzed so far [11]. Further data strongly indicate that H-type strains are genetically heterogeneous and often lack one or more of the SC1 and/or SC3 genes [11][42]. This loss of genetic information can be construed as an erosive process, in which H-type strains derive from a strain harboring intact SC1 and SC3 and developed towards strains that lack these genetic elements. To integrate this into the researchers' model, the researchers postulate the existence of an ancestral H-type variant with intact and functional SC1 and SC3 clusters that is represented by strain CBS 324.65.

Based on the currently available genomic information (summarized in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4), the researchers propose the model that is depicted in Figure 1; it suggests that the H-type is the ancestor rather than the successor of the A-type. The H-type comprises a heterogeneous group of strains that have in common the presence of the SC1 and SC3 and the absence of the SC2 but differ with respect to the genetic erosion of the SC1 and SC3. The model takes four findings into account: (1) the presence of truncated atr1 sequences in the S-type strains (Figure S3), (2) the presence of incomplete SC3 clusters in H-type strains, (3) the truncated SC1-down-1 gene in the A-type strain, and (4) the loss of the SC3 and the sat1 gene in the atypical S-type strain 51-11. The model implies that H-type strains represent a crucial element for a better understanding of the evolution of the S. chartarum genotypes.

Figure 2. Satratoxin clusters 1–3 (SC1-3, (A–C)) and the core trichothecene cluster (CTC) of S. chartarum strains 51-11, IBT 40293, IBT 7711 (genotype S strains), and IBT 40288 (genotype A strain). Arrows depict genes; the different gene clusters are boxed. A dotted line indicates that a sequence is not existent in the respective genome. The genes in square brackets (Panel C) are annotated to a different scaffold than the other genes of these strains, but the PCR and sequencing results demonstrate for IBT 40293 that these regions are part of a continuous sequence. (Panel A) also shows a region of three homologous genes of the Purpureocillium lilacinum isolate PLBJ-1 for comparison. The brown arrows in (Panel C) indicate a set of four genes that are present in all four strains.

Figure 3. The atranone cluster 1 (AC1) region annotated for four S. chartarum strains. Arrows indicate genes. The boxed genes represent the AC1. Genes in square brackets are not part of the scaffold harboring AC1 and/or its upstream region but reside instead in other scaffolds. (IBT 7711: upstream = scaffolds 1183 and (1150)), IBT 40293: upstream = scaffold 1452; downstream = (scaffold 1474)), IBT 40288: scaffold 1 and 51-11: upstream = scaffold 47; downstream are five genes of scaffold (127) and two genes of scaffold (11)). An identical coloration indicates affiliation to a common scaffold in the respective strain.

Figure 4. The atranone cluster 2 (AC2) region annotated for S. chartarum strains IBT 7711, IBT 40293, IBT 40288, and 51-11. Arrows indicate genes. The boxed genes represent the AC2 and encode the hypothetical proteins: S40288_09035, S40288_11459, S40288_09036, S40288_09037, S40288_09038, and S40288_11460 (from left to right). Genes in square brackets are not part of the scaffold harboring the AC2 but reside in other scaffolds. An identical coloration indicates affiliation to a common scaffold in the respective strain that is distinct from that harboring the AC2.

Another essential question that arises from the current research is how the different gene clusters collaborate to facilitate the production of mycotoxins, e.g., satratoxins and atranones. Usually, gene clusters contain so-called backbone biosynthesis genes for the production of individual mycotoxins. Genes that are engaged in the same secondary pathway commonly form gene clusters that are stable and rarely divided [46][47]. In S. chartarum, three clusters have been implicated in the biosynthesis of satratoxins despite the fact that they are spread in the genome. This situation is similar for the gene clusters that enable the synthesis of the T-2 toxin in Fusarium sporotrichioides [48][49], which is chemically closely related to the satratoxins. A physical separation of gene clusters suggests that they have different functions but does not exclude synergistic interactions. All three SC harbor one putative transcription factor (SC1: Sat9, SC2: Sat15, and SC3: Sat20). This pattern is often found for secondary metabolite clusters and allows a separate regulation for each set of genes. Apart from the biosynthesis, mycotoxins have to be released into the environment. Major Facilitator Superfamily (MFS) transporters have been implicated in this process [50]. It is remarkable that the only MFS protein encoded by the sat genes is Sat21, which is encoded in the SC3. Semeiks et al. [34] therefore assumed that the SC3 plays an important role in the transport of trichothecenes, a notion that is further supported by the fact that the SC3 and the CTC reside next to each other. The fact that the atranone-producing strains either lack a SC3 cluster (A-type) or often lack the sat21 gene (certain H-type strains) [42], indicating that atranones are most likely exported via a mechanism that does not involve Sat21. How the proteins that are encoded by the SC clusters interact and cooperate is still an open question. Whether the mycotoxin biosynthesis takes place in the cytoplasm or whether certain steps are concentrated in certain intracellular compartments or organelles is another. Sat10 is a further noticeable SC-encoded protein. It comprises 16 ankyrin repeat domains and is therefore supposed to be a scaffolding protein that interacts with other Sat proteins to coordinate their activities. The sat10 gene is the last gene of the SC1 cluster. Using BlastN, the researchers found that the two S. chartarum genes downstream of the SC1 are well conserved in the fungus Purpureocillium lilacinum. Strikingly, a neighboring gene shows high homology to sat10 and also encodes a protein with 16 ankyrin repeat proteins. The fact that these three genes are well conserved both with respect to their sequence and their orientation strongly suggests that they form a genetic element that was transferred from S. chartarum to P. lilacinum or vice versa. Such a horizontal gene transfer has been described for other fungal genes, e.g., for those involved in the sterigmatocystin synthesis in Aspergillus species [51][52]. Similar mechanism may have also enabled the transfer of MT-related genes to or from Myrothecium species. The fact that the plant Baccharis mesapotamica is able to produce roridins and verrucarins even suggests the possibility of an inter-kingdom transfer of genetic information [53][54].

Three distinct mechanisms can drive the evolution of functionally diverse gene clusters: de novo assembly, functional divergence, and horizontal transfer [38]. De novo assembly is the most time-consuming and therefore difficult step; it is required to generate an initial gene cluster that can then develop further. The BlastP searches identified proteins with substantial homology to Sat or ATR proteins in a variety of fungal species, and in most cases, the domains present in the Sat or Atr proteins are also well conserved. Remarkably, only few species harbored several of these genes in their genome. S. elegans is one example, and its genome contains three genes encoding proteins that are homologous to Sat1, Sat2, and Sat3, but strikingly, these genes are not clustered. Hence, a pool of fungal genes exist that is scattered over many species and likely provided the raw material for the assembly of gene clusters, such as those comprising the sat and atr genes. It is likely that the assembly of such clusters occurs gradually starting with small clusters that are successively enlarged by additional genes. The identification of the gene cluster in Monosporascus spp. and Xylaria grammica indicate that gene assemblies that are related to SC2 and SC3 exist in other fungi. A closer analysis and comparison of these clusters may provide further important insights. Functional divergence could explain how the SC2 emerged from a duplication of the CTC. Alternatively, the CTC and SC2 may derive from a common ancestor, and the Monosporascus gene cluster in fact appears to be a chimera of CTC and SC2. The presence of similar gene clusters in S. chartarum and other fungi strongly suggest that horizontal gene transfer played an important role in the evolution of the sat and atr gene clusters.

References

- Lombard, L.; Houbraken, J.; Decock, C.; Samson, R.A.; Meijer, M.; Réblová, M.; Groenewald, J.Z.; Crous, P.W. Generic hyper-diversity in Stachybotriaceae. Pers. Mol. Phylogeny Evol. Fungi 2016, 36, 156–246.

- Andersen, B.; Nielsen, K.F.; Jarvis, B.B. Characterization of Stachybotrys from water-damaged buildings based on morphology, growth, and metabolite production. Mycologia 2002, 94, 392–403.

- Institute, W.F.B. Mycobank. Available online: https://www.mycobank.org/ (accessed on 30 January 2021).

- Crous, P.W.; Gams, W.; Stalpers, J.A.; Robert, V.; Stegehuis, G. MycoBank: An online initiative to launch mycology into the 21st century. Stud. Mycol. 2004, 50, 19–22.

- Nielsen, K.F.; Huttunen, K.; Hyvarinen, A.; Andersen, B.; Jarvis, B.B.; Hirvonen, M.R. Metabolite profiles of Stachybotrys isolates from water-damaged buildings and their induction of inflammatory mediators and cytotoxicity in macrophages. Mycopathologia 2002, 154, 201–205.

- Wang, Y.; Hyde, K.D.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Jiang, Y.-L.; Li, D.-W.; Zhao, D.-G. Overview of Stachybotrys (Memnoniella) and current species status. Fungal Divers. 2015, 71, 17–83.

- Biermaier, B.; Gottschalk, C.; Schwaiger, K.; Gareis, M. Occurrence of Stachybotrys chartarum chemotype S in dried culinary herbs. Mycotoxin Res. 2015, 31, 23–32.

- El-Kady, I.A.; Moubasher, M.H. Toxigenicity and toxins of Stachybotrys isolates from wheat straw samples in Egypt. Exp. Mycol. 1982, 6, 25–30.

- Ulrich, S.; Gottschalk, C.; Biermaier, B.; Bahlinger, E.; Twarużek, M.; Asmussen, S.; Schollenberger, M.; Valenta, H.; Ebel, F.; Dänicke, S. Occurrence of type A, B and D trichothecenes, zearalenone and stachybotrylactam in straw. Arch. Anim. Nutr. 2021, 75, 105–120.

- Andersen, B.; Nielsen, K.F.; Thrane, U.; Szaro, T.; Taylor, J.W.; Jarvis, B.B. Molecular and phenotypic descriptions of Stachybotrys chlorohalonata sp. nov. and two chemotypes of Stachybotrys chartarum found in water-damaged buildings. Mycologia 2003, 95, 1227–1258.

- Ulrich, S.; Niessen, L.; Ekruth, J.; Schäfer, C.; Kaltner, F.; Gottschalk, C. Truncated satratoxin gene clusters in selected isolates of the atranone chemotype of Stachybotrys chartarum (Ehrenb.) S. Hughes. Mycotoxin Res. 2020, 36, 83–91.

- Jarvis, B.B.; Sorenson, W.G.; Hintikka, E.L.; Nikulin, M.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, J.; Wang, S.; Hinkley, S.; Etzel, R.A.; Dearborn, D. Study of toxin production by isolates of Stachybotrys chartarum and Memnoniella echinata isolated during a study of pulmonary hemosiderosis in infants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998, 64, 3620–3625.

- Hinkley, S.F.; Moore, J.A.; Squillari, J.; Tak, H.; Oleszewski, R.; Mazzola, E.P.; Jarvis, B.B. New atranones from the fungus Stachybotrys chartarum. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2003, 41, 337–343.

- Hinkley, S.F.; Jiang, J.; Mazzola, E.P.; Jarvis, B.B. Atranones: Novel diterpenoids from the toxigenic mold Stachybotrys atra. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999, 40, 2725–2728.

- Hanelt, M.; Gareis, M.; Kollarczik, B. Cytotoxicity of mycotoxins evaluated by the MTT-cell culture assay. Mycopathologia 1994, 128, 167–174.

- Hernández, F.; Cannon, M. Inhibition of protein synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by the 12,13-epoxytrichothecenes trichodermol, diacetoxyscirpenol and verrucarin A. Reversibility of the effects. J. Antibiot. 1982, 35, 875–881.

- Rocha, O.; Ansari, K.; Doohan, F.M. Effects of trichothecene mycotoxins on eukaryotic cells: A review. Food Addit. Contam. 2005, 22, 369–378.

- Ueno, Y. Trichothecenes-Chemical, Biological and Toxicological Aspects; Elsevier Science Publisher B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1983.

- Karunasena, E.; Larranaga, M.D.; Simoni, J.S.; Douglas, D.R.; Straus, D.C. Building-associated neurological damage modeled in human cells: A mechanism of neurotoxic effects by exposure to mycotoxins in the indoor environment. Mycopathologia 2010, 170, 377–390.

- Dearborn, D.G.; Smith, P.G.; Dahms, B.B.; Allan, T.M.; Sorenson, W.G.; Montana, E.; Etzel, R.A. Clinical profile of 30 infants with acute pulmonary hemorrhage in Cleveland. Pediatrics 2002, 110, 627–637.

- Miller, J.D.; Rand, T.G.; Jarvis, B.B. Stachybotrys chartarum: Cause of human disease or media darling? Med. Mycol. 2003, 41, 271–291.

- CDC. Pulmonary hemorrhage/hemosiderosis among infants Cleveland, Ohio, 1993/1996. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2002, 49, 180–184.

- Johanning, E.; Biagini, R.; Hull, D.; Morey, P.; Jarvis, B.; Landsbergis, P. Health and immunology study following exposure to toxigenic fungi (Stachybotrys chartarum) in a water-damaged office environment. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 1996, 68, 207–218.

- Hintikka, E.-L. The Role of Stachybotrys in the Phenomenon Known as Sick Building Syndrome. In Advances in Applied Microbiology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004; Volume 55, pp. 155–173.

- Nikulin, M.; Reijula, K.; Jarvis, B.B.; Hintikka, E.L. Experimental lung mycotoxicosis in mice induced by Stachybotrys atra. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 1996, 77, 213–218.

- Vesper, S.; Dearborn, D.G.; Yike, I.; Allan, T.; Sobolewski, J.; Hinkley, S.F.; Jarvis, B.B.; Haugland, R.A. Evaluation of Stachybotrys chartarum in the house of an infant with pulmonary hemorrhage: Quantitative assessment before, during, and after remediation. J. Urban Health 2000, 77, 68–85.

- Forgacs, J.; Carll, W.T.; Herring, A.S.; Hinshaw, W.R. Toxicity of Stachybotrys atra for animals. Trans. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1958, 20, 787–808.

- Schneider, D.J.; Marasas, W.F.; Dale Kuys, J.C.; Kriek, N.P.; Van Schalkwyk, G.C. A field outbreak of suspected stachybotryotoxicosis in sheep. J. S. Afr. Vet. Assoc. 1979, 50, 73–81.

- Kriek, N.P.J.; Marasas, W.F.O. Field outbreak of ovine stachybotryotoxicosis in South Africa. In Thrichothecenes-Chemical, Biological and Toxicological Aspects; Ueno, Y., Ed.; Elsevier Science Publisher B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1983; pp. 279–284.

- Semis, M.; Dadwal, S.S.; Tegtmeier, B.R.; Wilczynski, S.P.; Ito, J.I.; Kalkum, M. First Case of Invasive Stachybotrys Sinusitis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 72, 1386–1391.

- Vesper, S.J.; Magnuson, M.L.; Dearborn, D.G.; Yike, I.; Haugland, R.A. Initial characterization of the hemolysin stachylysin from Stachybotrys chartarum. Infect. Immun. 2001, 69, 912–916.

- Johanning, E.; Landsbergis, P.; Gareis, M.; Yang, C.S.; Olmsted, E. Clinical experience and results of a Sentinel Health Investigation related to indoor fungal exposure. Environ. Health Perspect. 1999, 107, 489–494.

- Rand, T.G.; Flemming, J.; David Miller, J.; Womiloju, T.O. Comparison of inflammatory responses in mouse lungs exposed to atranones A and C from Stachybotrys chartarum. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health 2006, 69, 1239–1251.

- Semeiks, J.; Borek, D.; Otwinowski, Z.; Grishin, N.V. Comparative genome sequencing reveals chemotype-specific gene clusters in the toxigenic black mold Stachybotrys. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 590.

- Vining, L.C. Secondary Metabolism; VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 1986.

- Medema, M.H.; Kottmann, R.; Yilmaz, P.; Cummings, M.; Biggins, J.B.; Blin, K.; de Bruijn, I.; Chooi, Y.H.; Claesen, J.; Coates, R.C.; et al. Minimum Information about a Biosynthetic Gene cluster. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015, 11, 625–631.

- Degenkolb, T.; Dieckmann, R.; Nielsen, K.F.; Gräfenhan, T.; Theis, C.; Zafari, D.; Chaverri, P.; Ismaiel, A.; Brückner, H.; von Döhren, H.; et al. The Trichoderma brevicompactum clade: A separate lineage with new species, new peptaibiotics, and mycotoxins. Mycol. Prog. 2008, 7, 177–219.

- Rokas, A.; Mead, M.E.; Steenwyk, J.L.; Raja, H.A.; Oberlies, N.H. Biosynthetic gene clusters and the evolution of fungal chemodiversity. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2020, 37, 868–878.

- Palmer, M.A.; Menninger, H.L.; Bernhardt, E. River restoration, habitat heterogeneity and biodiversity: A failure of theory or practice? Freshw. Biol. 2010, 55, 205–222.

- Hoogendoorn, K.; Barra, L.; Waalwijk, C.; Dickschat, J.S.; van der Lee, T.A.J.; Medema, M.H. Evolution and Diversity of Biosynthetic Gene Clusters in Fusarium. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1158.

- Alexander, W.G.; Wisecaver, J.H.; Rokas, A.; Hittinger, C.T. Horizontally acquired genes in early-diverging pathogenic fungi enable the use of host nucleosides and nucleotides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 4116.

- Kock, J.; Gottschalk, C.; Ulrich, S.; Schwaiger, K.; Gareis, M.; Niessen, L. Rapid and selective detection of macrocyclic trichothecene producing Stachybotrys chartarum strains by loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP). Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2021, 413, 4801–4813.

- Vesper, S.J.; Dearborn, D.G.; Yike, I.; Sorenson, W.G.; Haugland, R.A. Hemolysis, toxicity, and randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis of Stachybotrys chartarum strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 3175–3181.

- Martyn, R.D. Monosporascus Root Rot and Vine Decline of Melons (MRR/VD). Also referred to as sudden wilt, sudden death, melon collapse, Monosporascus wilt, and black pepper root rot. Plant Health Instr. 2002, 10, 0612-01.

- Zhu, M.; Cen, Y.; Ye, W.; Li, S.; Zhang, W. Recent Advances on Macrocyclic Trichothecenes, Their Bioactivities and Biosynthetic Pathway. Toxins 2020, 12, 417.

- Sidhu, G.S. Mycotoxin Genetics and Gene Clusters. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2002, 108, 705–711.

- Alexander, N.J.; Proctor, R.H.; McCormick, S.P. Genes, gene clusters, and biosynthesis of trichothecenes and fumonisins in Fusarium. Toxin Rev. 2009, 28, 198–215.

- Proctor, R.H.; McCormick, S.P.; Alexander, N.J.; Desjardins, A.E. Evidence that a secondary metabolic biosynthetic gene cluster has grown by gene relocation during evolution of the filamentous fungus Fusarium. Mol. Microbiol. 2009, 74, 1128–1142.

- Rokas, A.; Wisecaver, J.H.; Lind, A.L. The birth, evolution and death of metabolic gene clusters in fungi. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 731–744.

- Coleman, J.J.; Mylonakis, E. Efflux in fungi: La piece de resistance. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000486.

- Slot, J.C.; Rokas, A. Horizontal transfer of a large and highly toxic secondary metabolic gene cluster between fungi. Curr. Biol. 2011, 21, 134–139.

- Shen, L.; Porée, F.H.; Gaslonde, T.; Lalucque, H.; Chapeland-Leclerc, F.; Ruprich-Robert, G. Functional characterization of the sterigmatocystin secondary metabolite gene cluster in the filamentous fungus Podospora anserina: Involvement in oxidative stress response, sexual development, pigmentation and interspecific competitions. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 21, 3011–3026.

- Sun, B.F.; Xiao, J.H.; He, S.; Liu, L.; Murphy, R.W.; Huang, D.W. Multiple interkingdom horizontal gene transfers in Pyrenophora and closely related species and their contributions to phytopathogenic lifestyles. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60029.

- Fitzpatrick, D.A. Horizontal gene transfer in fungi. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2012, 329, 1–8.

More

Information

Subjects:

Evolutionary Biology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

794

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

19 Apr 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No