Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kyriaki Psara | + 3102 word(s) | 3102 | 2022-03-21 07:27:01 | | | |

| 2 | Beatrix Zheng | -42 word(s) | 3060 | 2022-03-24 10:31:35 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Psara, K. Barriers Related to Data-Driven Services across Electricity Sectors. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20973 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Psara K. Barriers Related to Data-Driven Services across Electricity Sectors. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20973. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Psara, Kyriaki. "Barriers Related to Data-Driven Services across Electricity Sectors" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20973 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Psara, K. (2022, March 24). Barriers Related to Data-Driven Services across Electricity Sectors. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20973

Psara, Kyriaki. "Barriers Related to Data-Driven Services across Electricity Sectors." Encyclopedia. Web. 24 March, 2022.

Copy Citation

Data-driven services offer a major shift away from traditional monitoring and control approaches that have been applied exclusively over the transmission and distribution networks. These services assist the electricity value chain stakeholders to enhance their data reach and improve their internal intelligence on electricity-related optimization functions. However, the penetration of data-driven services within the energy sector poses challenges across the regulatory, socioeconomic, and organizational (RSEO) domains that are specific to such business models.

regulations

socioeconomic

organizations

barriers

data-driven

1. Introduction

Under the traditional top-down business model, power system optimization relies on centralized decisions based on data silos preserved by the electricity sector stakeholders. The European energy sector is in the process of a major shift from a traditional centralized structure to a more inclusive system that incorporates digitalization, includes a wider variety of stakeholders, and requires new organizational processes. This major shift of the energy sector towards decarbonization and digitization has brought a plethora of reasons that have made data acquisition/analytics a “game-changer” for the stakeholders across the energy value chain. A study performed by the key players of the information and communications technology (ICT) industry, such as computer software and hardware corporations, claims that the big data analytics market in the energy sector is expected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 11.28% in 2021–2026 [1]. Advanced computing power, declining costs of information and communications technology, and the rollout of smart meters have dramatically increased the availability of data and the subsequent opportunities to extract intrinsic value. Furthermore, the scarcity of fossil fuels, the volatility of oil and gas prices, and the overarching challenge of climate change mitigation have driven major advances in renewable energy source (RES) technologies which in turn have led to RESs reaching grid parity conditions in terms of their total expenditure (TOTEX) [2] compared with the fossil alternatives.

RES grid and market integration, however, poses significant challenges for grid and system planning and operation [3]. Additionally, small-scale, nondispatchable renewables from prosumers, electric vehicle (EV) market growth, local and centralized energy storage, and implicit/explicit demand response channel the complexity of the electricity system’s energy balance through a dynamic market-signal-based consumption market. This complexity, along with the rising number of active actors which are required to fill these emerging service sectors (e.g., aggregators, energy service companies, EV charging infrastructure providers, facility managers), creates new needs for data exchanges and data analytics. Acknowledging the new data-driven energy sector environment, organizations from the whole spectrum of the electricity value chain (commercial, public, or research and academia) aim at benefiting from the use of innovative energy services (IESs) that rely on data analytics, either by investing in in-house development or by purchasing market-available solutions.

The successful adoption of these changes is reliant on considering the relevant regulatory, socioeconomic, and organizational (RSEO) factors needed for the successful integration of new services. In order to mitigate energy and price imbalances, European countries are in the process of interconnecting their power systems and coupling their energy markets, as well as standardizing related equipment and processes. Consideration of the regulatory elements is necessary to align any new initiatives with current legislation. This, in turn, drives the development and gradual adoption of a common regulatory basis for the member countries, aiming to enhance environmental protection, promote emerging technologies, increase efficiency and stability of the interconnected power and energy system, increase the efficiency of the building stock, and eliminate energy poverty [4]. At the same time, this regulatory transition will allow enough freedom for energy markets to grow and relevant stakeholders to profit within the boundaries of a healthy and prosperous commercial environment. In order to ensure that this transition does not overstress member countries and to safeguard the success of this systemic effort, various factors must be taken into consideration, such as societal norms, economic background, and prevailing mentality at an interorganizational level in the energy sector of each country. Respecting the socioeconomic factors, such as societal attitudes, motivations, and the distribution of wealth, ensures that the context in which the innovation is deployed is taken into account. Understanding a company’s processes and capabilities is important as the organizations are ultimately responsible for implementing the proposed changes. Consequently, a thorough country-based investigation of the potential regulatory and socioeconomic barriers as well as a stakeholder-type-based investigation of the organizational barriers to the adoption of innovative energy services (IESs) is necessary.

2. Current Insights

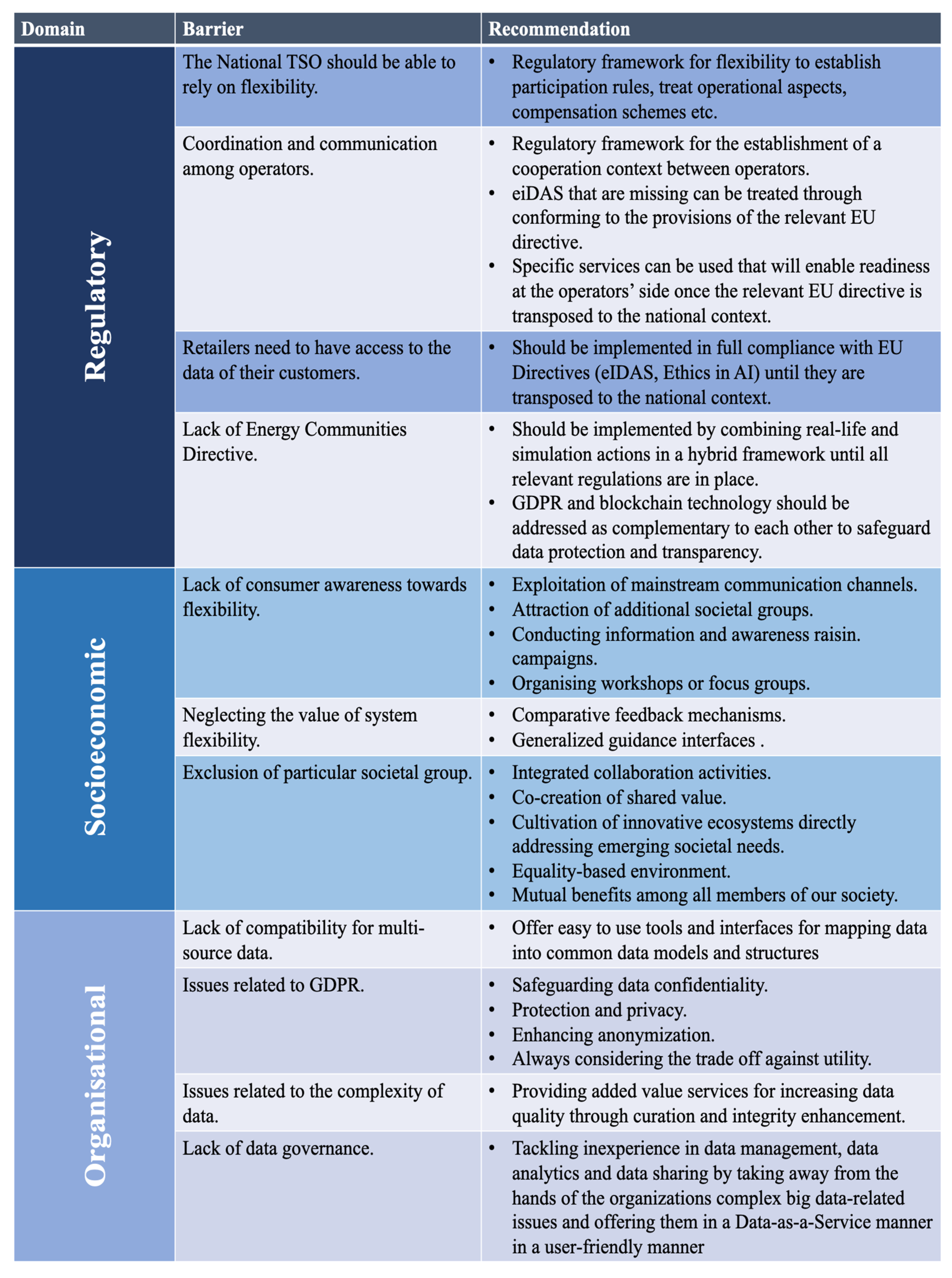

The quantitative analysis has provided valuable descriptive data on relevant barriers for countries and SH groups. However, an essential next step of this research was to build on these quantitative data through a qualitative analysis via interviews. These highlights, along with the remaining points raised from the researchers' analysis, provide useful inputs for the data-driven energy platform design, as well as further focus points on identifying and facilitating ways to overcome them. A summary of these outcomes can be observed in Figure 1. The inputs from the regulatory, socioeconomic, and organizational analyses were utilized to design interviews that aimed to specifically address any discrepancies identified from the above analyses, elaborate on any other barriers that the SYNERGY partners may foresee, and provide the opportunity to discuss practical implementation aspects. An initial stakeholder group was created with the aim to include a diversified and complete cluster of representative experts from the European electricity data value chain from partner organizations participating in SYNERGY.

Figure 1. Summarized outcomes of the research.

The overall regulatory analysis indicated that no significant barriers exist in implementing data-driven services in the countries of Greece, Spain, Finland, Austria, and Croatia, and where minor barriers do still exist, they are expected to be addressed by mid-2021. For the regulatory aspects where there is still an absence of related regulations, such as for blockchain, data-driven platforms can be developed to facilitate transparency and flexibility in complying with future regulations.

A flexibility-related regulation/legislation allows the national TSOs to rely on the flexibility offered by flexible asset owners in order to safeguard network resilience and power adequacy. This has been realized through the implementation of flexible power auctions. At the same time, although there is no blocking regulation for the establishment of a flexibility market for the distribution level, there is a lack of an appropriate regulatory framework that will enable the launch of a flexibility market at the LV and MV level and (lack of) relevant incentives towards the D&T network operators. Such a regulatory framework would be necessary to establish participation rules, treat operational aspects, implement compensation schemes, etc.

The integrated approach of the grid dictates coordination and communication among operators such as distribution and transmission system operators. This may also include active entities that may play an important role in the operational scheduling such as energy communities as suggested by the related directive. In any case, there is no blocking regulation for the establishment of a cooperation context between operators, but there is a lack of an appropriate regulatory framework. eIDAS that are missing can be treated through conforming to the provisions of the relevant EU directive that is expected to be transposed to the national regulatory framework.

The integrated approach of the grid and the unified energy value chain dictates coordination and communication among operators for addressing operational challenges such as network asset management and planning. The energy value chain includes important players such as energy communities that can be responsible for managing their own assets as suggested by the related directive that is in place. No specific restrictions or hindering factors are present in relation to network asset management, and to this end, specific services can be used that will enable readiness at the operators’ side once the relevant EU directive is transposed to the national context.

Retailers need to have access to the data of their customers either as a sole party or as an aggregated entity through other players in order to estimate/manage the given services to the network operators either through bilateral contracts or through the market. This needs to be implemented in full compliance with EU Directives (eIDAS, ethics in AI) until they are transposed to the national context.

The main targets in the energy domain of energy community self-consumption maximization and energy costs reduction could be realized according to the existing regulatory framework since they refer to the very essence of the energy communities. Currently, this should be implemented by combining real-life and simulation actions in a hybrid framework until all relevant regulations are in place in order to support transparent benefit sharing through the use of blockchain technology. Furthermore, GDPR and blockchain technology should be addressed as complementary to each other to safeguard data protection and transparency.

Regarding the most impactful barrier in the socioeconomic domain “Lack of consumer awareness for the benefits towards flexibility”, it is generally observed that consumers have a positive attitude towards smart appliances and shifting of consumption but are not willing to change their habits or experience a reduction in their comfort unless they achieve substantial financial benefits [5]. As such, the future electricity system should be able to provide opportunities to increase consumers’ engagement through greater awareness and participation. Increasing awareness and enhancing societal perception can be achieved through the exploitation of mainstream communication channels, the attraction of additional societal groups, conducting information and awareness-raising campaigns, and organizing workshops or focus groups.

Increasing consumer awareness will also alleviate the second barrier, which is “Neglecting the value of system flexibility”. The new system could empower consumers by giving them access to information and tools to understand their energy consumption and manage their bills. Several energy analytics solutions focus on engaging consumers in energy management strategies by mainly exploiting building energy reports, high-level analytics, comparative feedback, and benchmarks. These comparative feedback mechanisms and generalized guidance interfaces are used to achieve high customer engagement and provide appropriate feedback to consumers that can be easily understood and can be used to generate value.

Finally, the third barrier, “Exclusion of societal groups”, can be addressed by involving a variety of stakeholders and consumers, along with their associated communities, in integrated collaboration activities for cocreation of shared value and cultivation of innovative ecosystems directly addressing emerging societal needs. The future energy sector should be an equality-based environment that constitutes an intersection between policy, society, and economy that offers win–win outcomes and mutual benefits among all members of the society.

All organizational barriers point out that specific attention needs to be given to the development of appropriate mechanisms of data-driven services towards safeguarding data confidentiality, protection, and privacy; enhancing anonymization; always considering the trade-off against utility; offering easy-to-use tools and interfaces for mapping data into common data models and structures; providing added-value services for increasing data quality through curation and integrity enhancement; and tackling inexperience in data management, data analytics, and data sharing by taking complex big-data-related issues away from the hands of the organizations and offering them in a data-as-a-service manner in a user-friendly manner.

3. Conclusions

The survey identified whether appropriate regulations exist at a national level and their impact on data-driven services. Considering the national enforcement of the EU policies in the countries of SYNERGY’s consortium, Spain is found to be the one that currently presents the most regulatory gaps pertinent to SYNERGY innovation, compared to Greece, Austria, and Croatia. However, most missing regulations in Spain were expected to be in place by the end of 2020, while more specifically, regulation on energy communities was expected to be implemented by mid-2021. On the other hand, Finland is the only country that presents no regulatory gaps relative to the identified EU directives. Policies related to the introduction of new technologies such as Electronic Identification, Authentication and Trust Services; smart contracts and blockchain; or ethics in artificial intelligence are currently missing from almost all countries. On the contrary, legislation relative to smart metering has been applied to all countries. The overall regulatory analysis indicated, however, that no significant barriers exist in implementing data-driven services in the countries of Greece, Spain, Finland, Austria, and Croatia; where minor barriers do still exist, they are expected to be addressed in the upcoming years. For the regulatory aspects where there is still an absence of related regulation, such as for blockchain, data-driven platforms [6] can be proactively developed to facilitate transparency and flexibility in complying with future regulations.

During the quantitative analysis of the surveys, it was observed that a few discrepancies were identified attributed to the perception of the questionnaire respondents, either from a personal capacity in their business role and their comprehension of each regulation or the perceived impact that each regulation has on their company. One of the largest discrepancies was the respondents’ perception of GDPR. When it comes to asset management and network planning, asset-related data are usually used in combination with consumer data (i.e., smart meter data). It is, therefore, apparent that GDPR might be highly impactful for the DSO who manages the smart meters, i.e., third party data, but might be of much less importance to the TSO who is concerned with proprietary data whose utilization may be internally governed following already existing rules based on regulatory reporting standards. Perception differences in the way that respondents understand the existing impact or the potential impact that a directive might have could be seen in relation to green power purchase agreements (GPPAs) between RES operators and retailers. The difference in perception on whether the Energy Communities Legislation has significant impact could be attributed to the fact that this directive currently does not affect per se the establishment of GPPAs using energy coming from PV plants owned/operated by an RES operator; however, if the Energy Communities Legislation will not explicitly facilitate the participation of energy communities in such agreements, it might restrict the scalability of such agreements, as potentially large green energy production segments such as energy communities might be excluded from appropriate regulation concerning certification of GPPAs. These discrepancies provided input to the interviews performed as part of the methodology in the form of embedding the input from this perception analysis into specific questions that aimed at capturing any barriers foreseen by the participating data value chain actors. As the initial engagement through the interviews showed that no major barriers exist, or where there are complexities, measures such as internal governance procedures and experimental agreements can be put in place to overcome these barriers, these discrepancies were attributed to the personal perception of the survey respondents as part of their business role or the specific role of their organization in relation to data-driven practices.

The socioeconomic aspects related to data-driven services were studied by means of an initial comprehensive literature review targeting the identification of such barriers through prominent literature sources. This state-of-the-art analysis was complemented by the relevant survey towards the participants which offered results that relate to the national level. When aggregating the scores from all countries, three main SE barriers were demonstrated to be the most impactful above all others. The most impactful SE barrier was related to a lack of consumer awareness for the benefits towards flexibility, opportunity, cost saving, and revenue generation. The second and third highest rated SE barriers were neglecting the value of system flexibility and the exclusion of particular societal groups, respectively.

Similarly to the regulatory domain, multiple large discrepancies were identified between the responses due to multiple organizations contributing to the averaged impact scores in the SE barrier analysis. In addition to the analysis of the barriers per demo case, the variance of scores was calculated for the demo cases where multiple organizations responded to create an average score. The most conflicting barriers are “CAPEX”, “No sponsorship for CAPEX”, “Neglecting the value of system Flexibility”, “Lack of equal opportunities in wealth”, “Converting innovation into business as usual”, and “No consideration for diversity of interests”. Following up on these conflict barriers during the interviews allowed the researchers to identify why there is a difference of opinion between each organization with regard to a specific use of data-driven services. The CAPEX-related conflict barriers are highly dependent on the type of data processed by each organization. As such, any innovative data-driven business models need to be customized for the type of data processes and take into account also the cost of accessing assets that are not “connected assets” and as such require further infrastructure to enable data-sharing-driven business cases. Regarding system flexibility and business-as-usual innovation, regulation is driving innovation in the flexibility of energy systems, and when existing frameworks do not promote nor facilitate such innovation, it is hard for regulated entities and aggregators to create the necessary skills and processes required to facilitate such developments.

On the organizational level, some barriers are commonly highlighted in the results across almost all stakeholder types. The analysis done per stakeholder provides information on the most impactful barriers which affect a particular SH group across multiple organizations. It would be beneficial to investigate the barriers which are deemed important from the perspective of the SHs which are integral to data-driven services. When assessing the aggregated scores from all stakeholder types, the analysis presented here suggests there are four main impactful OR barriers. These barriers were related to a lack of compatibility for multisource data, issues related to GDPR, issues related to the complexity of data, and a lack of data governance.

The analysis done per stakeholder provides information on the most impactful barriers which affect a particular SH group across multiple organizations. It is therefore beneficial to investigate the difference in perspective of the surveyed stakeholders exhibiting a conflict of opinion with regard to the impact of organizational barriers. Such conflicting barriers include “Inability to recognize data value”, “Lack of data governance”, “Data complexity” and “Closed ICT systems”. To this end, during the interviews, questions related to these conflicting barriers were included in order to potentially provide an understanding of the perspective of each key SH. The interviews indicated that perception of data governance, recognition, and complexity is highly dependent on the type of data processed by each stakeholder (such as customer data, public infrastructure data, national interconnections data, and market data). In order to be able to analyze and derive insightful value from combining multisource data, the value of data from various sources should be clearly stated and understood. The recognition of data value can be increased by ensuring data quality, accuracy, and multisource compatibility, as well as exploiting data linking of information coming from different domains.

References

- Big Data Analytics Market in the Energy Sector–Growth, Trends, Covid-19 Impact, And Forecasts (2021–2026); Modor Intelligence: Telangana, India, 2021; Available online: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/big-data-in-energy-sector-industry (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- LAZARD, Levelized Cost of Energy Analysis—Version 14. Available online: https://www.lazard.com/media/451419/lazards-levelized-cost-of-energy-version-140.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Vom Scheidt, F.; Medinová, H.; Ludwig, N.; Richter, B.; Staudt, P.; Weinhardt, C. Data analytics in the electricity sector—A quantitative and qualitative literature review. Energy AI 2020, 1, 100009.

- Grillone, B.; Danov, S.; Sumper, A.; Cipriano, J.; Mor, G. A review of deterministic and data-driven methods to quantify energy efficiency savings and to predict retrofitting scenarios in buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 131, 110027.

- Kava, H.; Spanaki, K.; Papadopoulos, T.; Despoudi, S.; Rodriguez-Espindola, O.; Fakhimi, M. Data analytics diffusion in the UK renewable energy sector: An innovation perspective. Ann. Oper. Res. 2021, 1–26.

- Duch-Brown, N.; Rossetti, F. Digital platforms across the European regional energy markets. Energy Policy 2020, 144, 111612.

More

Information

Subjects:

Energy & Fuels

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

565

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

24 Mar 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No