| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Christine Struck | + 4079 word(s) | 4079 | 2022-03-23 03:51:35 | | | |

| 2 | Peter Tang | -51 word(s) | 4028 | 2022-03-24 03:10:24 | | |

Video Upload Options

Clubroot caused by the soil-living, obligate biotrophic protist Plasmodiophora brassicae Woronin belongs to the most devastating diseases of cruciferous crops worldwide. As with many plant pathogens, the spread is closely related to the cultivation of suitable host plants. In addition, temperature and water availability are crucial determinants for the occurrence and reproduction of clubroot disease. Current global changes are contributing to the widespread incidence of clubroot disease. On the one hand, global trade and high prices are leading to an increase in the cultivation of the host plant rapeseed worldwide. On the other hand, climate change is improving the living conditions of the pathogen P. brassicae in temperate climates and leading to its increased occurrence. Since chemical control of the clubroot disease is not possible or not ecologically compatible, more and more alternative control options are being investigated.

1. Introduction

2. Environmental Parameters Influencing Plasmodiophora brassicae Development

3. Agricultural Practices

3.1. Plant Resistance

3.2. Crop Rotation and Tillage

3.3. Field Sanitation

3.4. Soil pH

|

Lime Fertilizer |

Components (%) |

CaO Equivalent (%) |

pH of Soil (6 dpi) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

CaCO3 |

CaO |

MgO |

SO3 |

SO4 |

|||

|

Calcium carbonate |

80 |

--- |

--- |

--- |

--- |

45 |

6.44 |

|

CaCO3-Mg-lime I |

80 |

--- |

5 |

--- |

--- |

48 |

5.42 |

|

CaCO3-Mg-lime II |

50 |

--- |

35 |

--- |

--- |

19 |

6.39 |

|

CaSO4 |

68 |

--- |

1–2 |

--- |

4.5 |

38 |

6.58 |

|

Splitting lime I 1 |

80 + 75 |

--- |

--- |

+25 |

--- |

22.5 + 22.5 |

6.71 |

|

Splitting lime II 1 |

80 + 75 |

--- |

--- |

+25 |

--- |

45 + 45 |

6.72 |

|

Calcium oxide I |

--- |

38 |

3 |

--- |

--- |

38 |

7.00 |

|

Calcium oxide II |

--- |

90 |

1 |

--- |

0.3 |

90 |

7.34 |

|

Non-treated control |

--- |

--- |

--- |

--- |

--- |

--- |

4.90 |

|

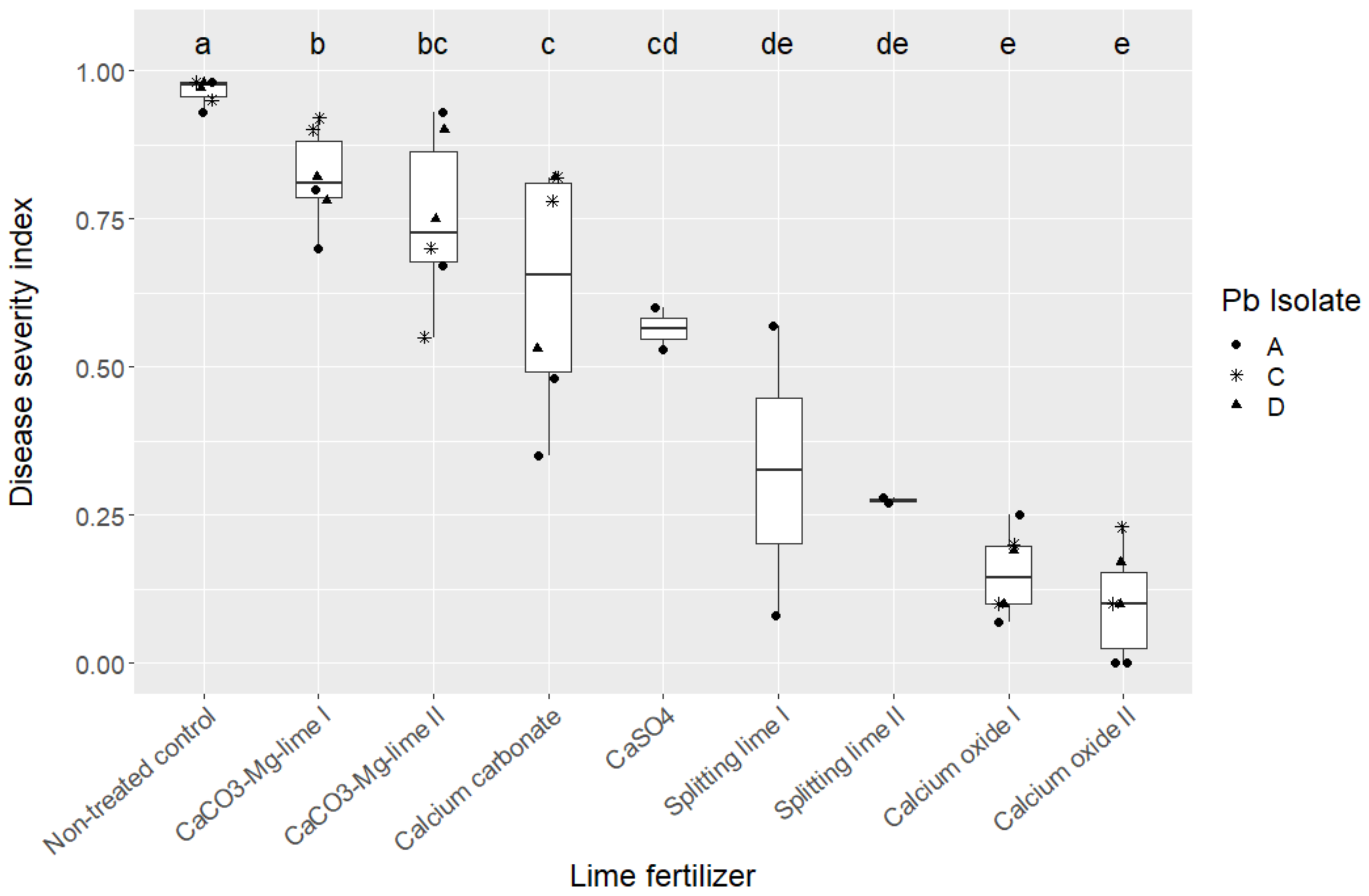

Lime Fertilizer |

DSI |

SD |

N |

IF (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Calcium carbonate |

0.63 |

0.28 |

120 |

86.67 |

|

CaCO3-Mg-lime 1 |

0.75 |

0.24 |

120 |

95.83 |

|

CaCO3-Mg-lime 2 |

0.82 |

0.25 |

160 |

96.67 |

|

CaSO4 |

0.57 |

0.28 |

40 |

82.50 |

|

Splitting lime 1 1 |

0.33 |

0.27 |

40 |

47.50 |

|

Splitting lime 2 1 |

0.28 |

0.08 |

40 |

40.00 |

|

Calcium oxide 1 |

0.15 |

0.25 |

120 |

29.60 |

|

Calcium oxide 2 |

0.10 |

0.15 |

120 |

23.33 |

|

Non-treated control |

0.97 |

0.08 |

120 |

100.00 |

1 Additional application of SO3-containing lime 6 days after inoculation.

4. Clubroot Control Using Beneficial Microorganisms

4.1. Antagonistic Bacteria

4.2. Antagonistic Fungi

5. Conclusions

References

- Dixon, G.R. The occurrence and economic impact of Plasmodiophora brassicae and clubroot disease. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2009, 28, 194–202.

- Zheng, X.; Koopmann, B.; Ulber, B.; Von Tiedemann, A. A global survey on diseases and pests in oilseed rape—Current challenges and innovative strategies of control. Front. Agron. 2020, 2, 590908.

- Cavalier-Smith, T.; Chao, E.E.-Y. Phylogeny and classification of phylum Cercozoa (Protozoa). Protist 2003, 154, 341–358.

- Burki, F.; Kudryavtsev, A.; Matz, M.V.; Aglyamova, G.V.; Bulman, S.; Fiers, M.; Keeling, P.J.; Pawlowski, J. Evolution of Rhizaria: New insights from phylogenomic analysis of uncultivated protists. BMC Evol. Biol. 2010, 10, 377.

- Cavalier-Smith, T.; Chao, E.E.; Lewis, R. Multigene phylogeny and cell evolution of chromist infrakingdom Rhizaria: Contrasting cell organisation of sister phyla Cercozoa and Retaria. Protoplasma 2018, 255, 1517–1574.

- Strehlow, B.; de Mol, F.; Struck, C. Risk potential of clubroot disease on winter oilseed rape. Plant Dis. 2015, 99, 667–675.

- Hwang, S.-F.; Strelkov, S.E.; Feng, J.; Gossen, B.D.; Howard, R.J. Plasmodiophora brassicae: A review of an emerging pathogen of the Canadian canola (Brassica napus) crop. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012, 13, 105–113.

- Malinowski, R.; Truman, W.; Blicharz, S. Genius architect or clever thief-how Plasmodiophora brassicae reprograms host development to establish a pathogen-oriented physiological sink. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2019, 32, 1259–1266.

- Botero-Ramirez, A.; Hwang, S.-F.; Strelkov, S.E. Plasmodiophora brassicae inoculum density and spatial patterns at the field level and relation to soil characteristics. Pathogens 2021, 10, 499.

- Woronin, M. Plasmodiophora brassicae, Urheber der Kohlpflanzen-Hernie. Jahrb. Wiss. Bot. 1878, 11, 548–574.

- Botero, A.; García, C.; Gossen, B.D.; Strelkov, S.E.; Todd, C.D.; Bonham-Smith, P.C.; Pérez-López, E. Clubroot disease in Latin America: Distribution and management strategies. Plant Pathol 2019, 68, 827–833.

- Donald, E.C.; Porter, I.J. Clubroot in Australia: The history and impact of Plasmodiophora brassicae in Brassica crops and research efforts directed towards its control. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2014, 36, 66–84.

- Dixon, G.R. Plasmodiophora brassicae in its Environment. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2009, 28, 212–228.

- Dixon, G.R. The occurrence and economic impact of Plasmodiophora brassicae and clubroot disease. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2009, 28, 194–202.

- Ernst, T.W.; Kher, S.; Stanton, D.; Rennie, D.C.; Hwang, S.F.; Strelkov, S.E. Plasmodiophora brassicae resting spore dynamics in clubroot resistant canola (Brassica napus) cropping systems. Plant Pathol. 2019, 68, 399–408.

- Dixon, G.R. Plasmodiophora brassicae in its Environment. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2009, 28, 212–228.

- Wallenhammar, A.-C. Prevalence of Plasmodiophora brassicae in a spring oilseed rape growing area in central Sweden and factors influencing soil infestation levels. Plant Pathol. 1996, 45, 710–719.

- Peng, G.; Pageau, D.; Strelkov, S.E.; Gossen, B.D.; Hwang, S.-F.; Lahlali, R. A >2-year crop rotation reduces resting spores of Plasmodiophora brassicae in soil and the impact of clubroot on canola. Eur. J. Agron. 2015, 70, 78–84.

- Yang, X.; Huang, X.; Wu, W.; Xiang, Y.; Du, L.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y. Effects of different rotation patterns on the occurrence of clubroot disease and diversity of rhizosphere microbes. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 2265–2273.

- Cook, W.R.I.; Schwartz, E.J., VI. The life-history, cytology and method of infection of Plasmodiophora brassiae Woron., the cause of finger-and-toe disease of cabbages and other crucifers. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 1930, 218, 450–461.

- Gossen, B.D.; Deora, A.; Peng, G.; Hwang, S.-F.; McDonald, M.R. Effect of environmental parameters on clubroot development and the risk of pathogen spread. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2014, 36, 37–48.

- Thuma, B.A.; Rowe, R.C.; Madden, L.V. Relationships of soil temperature and moisture to clubroot (Plasmodiophora brassicae) severity on radish in organic soil. Plant Dis. 1983, 67, 758–762.

- Sharma, K.; Gossen, B.D.; McDonald, M.R. Effect of temperature on primary infection by Plasmodiophora brassicae and initiation of clubroot symptoms. Plant Pathol. 2011, 60, 830–838.

- Gossen, B.D.; Adhikari, K.C.; McDonald, M.R. Effects of temperature on infection and subsequent development of clubroot under controlled conditions. Plant Pathol. 2012, 61, 593–599.

- Gravot, A.; Lemarié, S.; Richard, G.; Lime, T.; Lariagon, C.; Manzanares-Dauleux, M.J. Flooding affects the development of Plasmodiophora brassicae in Arabidopsis roots during the secondary phase of infection. Plant Pathol. 2016, 65, 1153–1160.

- Dobson, R.; Gabrielson, R.L.; Baker, A.S. Soil water matric potential requirements for root hair and cortical infection of Chinese cabbage by Plasmodiophora brassicae. Phytopathology 1982, 72, 1598–1600.

- Murakami, H.; Tsushima, S.; Kuroyanagi, Y.; Shishido, Y. Reduction of resting spore density of Plasmodiophora brassicae and clubroot disease severity by liming. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2002, 48, 685–691.

- Strehlow, B.; de Mol, F.; Struck, C. Standorteigenschaften und Anbaumanagement erklären regionale Unterschiede im Kohlherniebefall in Deutschland: Location and crop management affect clubroot severity in Germany. Gesunde Pflanz. 2014, 66, 157–164.

- Gossen, B.D.; Kasinathan, H.; Deora, A.; Peng, G.; McDonald, M.R. Effect of soil type, organic matter content, bulk density and saturation on clubroot severity and biofungicide efficacy. Plant Pathol. 2016, 65, 1238–1245.

- Niwa, R.; Nomura, Y.; Osaki, M.; Ezawa, T. Suppression of clubroot disease under neutral pH caused by inhibition of spore germination of Plasmodiophora brassicae in the rhizosphere. Plant Pathol. 2008, 57, 445–452.

- Rashid, A.; Ahmed, H.U.; Xiao, Q.; Hwang, S.F.; Strelkov, S.E. Effects of root exudates and pH on Plasmodiophora brassicae resting spore germination and infection of canola (Brassica napus L.) root hairs. Crop Protect. 2013, 48, 16–23.

- Macfarlane, I. A solution-culture technique for obtaining root hair or primary, infection by Plasmodiophora brassicae. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1958, 18, 720–732.

- Myers, D.F.; Campbell, R.N. Lime and the control of clubroot of Crucifers: Effects of pH, calcium, magnesium, and their interaction. Phytopathology 1985, 75, 670–673.

- Donald, E.C.; Porter, I.J. A sand–solution culture technique used to observe the effect of calcium and pH on root hair and cortical stages of infection by Plasmodiophora brassicae. Austral. Plant Pathol. 2004, 33, 585.

- Liao, J.; Luo, L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, L.; Shi, X.; Yang, H.; Tan, S.; Tan, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, D.; et al. Comparison of the effects of three fungicides on clubroot disease of tumorous stem mustard and soil bacterial community. J. Soils Sediments 2022, 22, 256–271.

- Donald, C.; Porter, I. Integrated control of Clubroot. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2009, 28, 289–303.

- Diederichsen, E.; Frauen, M.; Linders, E.G.A.; Hatakeyama, K.; Hirai, M. Status and perspectives of clubroot resistance breeding in crucifer crops. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2009, 28, 265–281.

- Piao, Z.; Ramchiary, N.; Lim, Y.P. Genetics of clubroot resistance in Brassica species. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2009, 28, 252–264.

- Rahman, H.; Peng, G.; Yu, F.; Falk, K.C.; Kulkarni, M.; Selvaraj, G. Genetics and breeding for clubroot resistance in Canadian spring canola (Brassica napus L.). Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2014, 36, 122–134.

- Lv, H.; Fang, Z.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y. An update on the arsenal: Mining resistance genes for disease management of Brassica crops in the genomic era. Hortic. Res. 2020, 7, 34.

- Hegewald, H.; Wensch-Dorendorf, M.; Sieling, K.; Christen, O. Impacts of break crops and crop rotations on oilseed rape productivity: A review. Eur. J. Agron. 2018, 101, 63–77.

- Zahr, K.; Sarkes, A.; Yang, Y.; Ahmed, H.; Zhou, Q.; Feindel, D.; Harding, M.W.; Feng, J. Plasmodiophora brassicae in its environment: Effects of temperature and light on resting spore survival in soil. Phytopathology 2021, 111, 1743–1750.

- Rennie, D.C.; Holtz, M.D.; Turkington, T.K.; Leboldus, J.M.; Hwang, S.-F.; Howard, R.J.; Strelkov, S.E. Movement of Plasmodiophora brassicae resting spores in windblown dust. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2015, 37, 188–196.

- Howard, R.J.; Strelkov, S.E.; Harding, M.W. Clubroot of cruciferous crops—new perspectives on an old disease. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2010, 32, 43–57.

- Hwang, S.-F.; Howard, R.J.; Strelkov, S.E.; Gossen, B.D.; Peng, G. Management of clubroot (Plasmodiophora brassicae) on canola (Brassica napus) in western Canada. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2014, 36, 49–65.

- Ren, L.; Xu, L.; Liu, F.; Chen, K.; Sun, C.; Li, J.; Fang, X. Host range of Plasmodiophora brassicae on cruciferous crops and weeds in China. Plant Dis. 2016, 100, 933–939.

- Zamani-Noor, N.; Rodemann, B. Reducing the build-up of Plasmodiophora brassicae inoculum by early management of oilseed rape volunteers. Plant Pathol. 2018, 67, 426–432.

- Campbell, R.N.; Greathead, A.S.; Myers, D.F.; de Boer, G.J. Factors related to control of clubroot of Crucifers in the salinas valley of California. Phytopathology 1985, 75, 665–670.

- Tremblay, N.; Bélec, C.; Coulombe, J.; Godin, C. Evaluation of calcium cyanamide and liming for control of clubroot disease in cauliflower. Crop Protect. 2005, 24, 798–803.

- Knox, O.; Oghoro, C.O.; Burnett, F.J.; Fountaine, J.M. Biochar increases soil pH, but is as ineffective as liming at controlling clubroot. J. Plant Pathol. 2015, 97, 149–152.

- McGrann, G.R.; Gladders, P.; Smith, J.A.; Burnett, F. Control of clubroot (Plasmodiophora brassicae) in oilseed rape using varietal resistance and soil amendments. Field Crop Res. 2016, 186, 146–156.

- Wakeham, A.; Faggian, R.; Kennedy, R. Assessment of the response of Plasmodiophora brassicae in contaminated horticultural land, using lime-based fertilizer concentrations. Food Energy Secur. 2017, 6, 84.

- Dixon, G.R. Managing clubroot disease (caused by Plasmodiophora brassicae Wor.) by exploiting the interactions between calcium cyanamide fertilizer and soil microorganisms. J. Agric. Sci. 2017, 155, 527–543.

- Webster, M.A.; Dixon, G.R. Calcium, pH and inoculum concentration influencing colonization by Plasmodiophora brassicae. Mycol. Res. 1991, 95, 64–73.

- Neuweiler, R.; Heller, W.E.; Kraus, J. Bekämpfung der Kohlhernie durch gezielte Düngungsmassnahmen. (Preventive effects of different fertilization strategies against the clubroot disease (Plasmodiophora brassicae)). AgrarForschung 2009, 16, 360–365.

- Niwa, R.; Kumei, T.; Nomura, Y.; Yoshida, S.; Osaki, M.; Ezawa, T. Increase in soil pH due to Ca-rich organic matter application causes suppression of the clubroot disease of crucifers. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2007, 39, 778–785.

- Tanaka, S.; Kochi, S.; Kunita, H.; Ito, S.; Kameya-Iwaki, M. Biological mode of action of the fungicide, flusulfamide, against Plasmodiophora brassicae (clubroot). Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 1999, 105, 577–584.

- Diederichsen, E.; Sacristan, M.D. Disease response of resynthesized Brassica napus L. lines carrying different combinations of resistance to Plasmodiophora brassicae Wor. Plant Breeding 1996, 115, 5–10.

- De Mendiburu, F. Agricolae: Statistical Procedures for Agricultural Research, R Package Version 1.3-5. 2021. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=agricolae (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Fox, N.M.; Hwang, S.-F.; Manolii, V.P.; Turnbull, G.; Strelkov, S.E. Evaluation of lime products for clubroot (Plasmodiophora brassicae) management in canola (Brassica napus) cropping systems. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2021, 44, 21–38.

- Jiang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Gan, G.; Li, W.; Wan, W.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Exploring rhizo-microbiome transplants as a tool for protective plant-microbiome manipulation. ISME COMMUN. 2022, 2, 1–10.

- Pliego, C.; Ramos, C.; de Vicente, A.; Cazorla, F.M. Screening for candidate bacterial biocontrol agents against soilborne fungal plant pathogens. Plant Soil 2011, 340, 505–520.

- Raymaekers, K.; Ponet, L.; Holtappels, D.; Berckmans, B.; Cammue, B.P. Screening for novel biocontrol agents applicable in plant disease management—A review. Biol. Control 2020, 144, 104240.

- Wu, L.; Wu, H.-J.; Qiao, J.; Gao, X.; Borriss, R. Novel routes for improving biocontrol activity of Bacillus based bioinoculants. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1395.

- Caulier, S.; Nannan, C.; Gillis, A.; Licciardi, F.; Bragard, C.; Mahillon, J. Overview of the antimicrobial compounds produced by members of the Bacillus subtilis group. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 302.

- Miljaković, D.; Marinković, J.; Balešević-Tubić, S. The significance of Bacillus spp. in disease suppression and growth promotion of field and vegetable crops. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1037.

- Sood, M.; Kapoor, D.; Kumar, V.; Sheteiwy, M.S.; Ramakrishnan, M.; Landi, M.; Araniti, F.; Sharma, A. Trichoderma: The “Secrets” of a multitalented biocontrol agent. Plants 2020, 9, 762.

- Alfiky, A.; Weisskopf, L. Deciphering Trichoderma-plant-pathogen interactions for better development of biocontrol applications. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 61.

- Zhu, M.; He, Y.; Li, Y.; Ren, T.; Liu, H.; Huang, J.; Jiang, D.; Hsiang, T.; Zheng, L. Two new biocontrol agents against clubroot caused by Plasmodiophora brassicae. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 3099.

- Mazzola, M.; Freilich, S. Prospects for biological soilborne disease control: Application of indigenous versus synthetic microbiomes. Phytopathology 2017, 107, 256–263.

- Caulier, S.; Nannan, C.; Gillis, A.; Licciardi, F.; Bragard, C.; Mahillon, J. Overview of the antimicrobial compounds produced by members of the Bacillus subtilis group. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 302.

- Miljaković, D.; Marinković, J.; Balešević-Tubić, S. The significance of Bacillus spp. in disease suppression and growth promotion of field and vegetable crops. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1037.

- Ongena, M.; Jacques, P. Bacillus lipopeptides: Versatile weapons for plant disease biocontrol. Trends Microbiol. 2008, 16, 115–125.

- Fira, D.; Dimkić, I.; Berić, T.; Lozo, J.; Stanković, S. Biological control of plant pathogens by Bacillus species. J. Biotechnol. 2018, 285, 44–55.

- Li, X.-Y.; Mao, Z.-C.; Wang, Y.-H.; Wu, Y.-X.; He, Y.-Q.; Long, C.-L. Diversity and active mechanism of fengycin-type cyclopeptides from Bacillus subtilis XF-1 against Plasmodiophora brassicae. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 23, 313–321.

- Guo, S.; Zhang, J.; Dong, L.; Li, X.; Asif, M.; Guo, Q.; Jiang, W.; Ma, P.; Zhang, L. Fengycin produced by Bacillus subtilis NCD-2 is involved in suppression of clubroot on Chinese cabbage. Biol. Control 2019, 136, 104001.

- He, P.; Cui, W.; Munir, S.; He, P.; Li, X.; Wu, Y.; Yang, X.; Tang, P.; He, Y. Plasmodiophora brassicae root hair interaction and control by Bacillus subtilis XF-1 in Chinese cabbage. Biol. Control 2019, 128, 56–63.

- Liu, C.; Yang, Z.; He, P.; Munir, S.; Wu, Y.; Ho, H.; He, Y. Deciphering the bacterial and fungal communities in clubroot-affected cabbage rhizosphere treated with Bacillus subtilis XF-1. Agr. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 256, 12–22.

- Mendis, H.C.; Thomas, V.P.; Schwientek, P.; Salamzade, R.; Chien, J.-T.; Waidyarathne, P.; Kloepper, J.; de La Fuente, L. Strain-specific quantification of root colonization by plant growth promoting rhizobacteria Bacillus firmus I-1582 and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens QST713 in non-sterile soil and field conditions. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193119.

- Peng, G.; McGregor, L.; Lahlali, R.; Gossen, B.D.; Hwang, S.F.; Adhikari, K.K.; Strelkov, S.E.; McDonald, M.R. Potential biological control of clubroot on canola and crucifer vegetable crops. Plant Pathol. 2011, 60, 566–574.

- Gossen, B.D.; Kasinathan, H.; Deora, A.; Peng, G.; McDonald, M.R. Effect of soil type, organic matter content, bulk density and saturation on clubroot severity and biofungicide efficacy. Plant Pathol. 2016, 65, 1238–1245.

- Lahlali, R.; Peng, G.; McGregor, L.; Gossen, B.D.; Hwang, S.F.; McDonald, M. Mechanisms of the biofungicide Serenade (Bacillus subtilis QST713) in suppressing clubroot. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2011, 21, 1351–1362.

- Lahlali, R.; Peng, G.; Gossen, B.D.; McGregor, L.; Yu, F.Q.; Hynes, R.K. Evidence that the biofungicide Serenade (Bacillus subtilis) suppresses clubroot on canola via antibiosis and induced host resistance. Phytopathology 2013, 103, 245–254.

- Zhu, M.; He, Y.; Li, Y.; Ren, T.; Liu, H.; Huang, J.; Jiang, D.; Hsiang, T.; Zheng, L. Two new biocontrol agents against clubroot caused by Plasmodiophora brassicae. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 3099.

- Expósito, R.G.; Postma, J.; Raaijmakers, J.M.; de Bruijn, I. Diversity and activity of Lysobacter species from disease suppressive soils. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1243.

- Zhou, L.; Zhang, L.; He, Y.; Liu, F.; Li, M.; Wang, Z.; Ji, G. Isolation and characterization of bacterial isolates for biological control of clubroot on Chinese cabbage. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2014, 140, 159–168.

- Shakeel, Q.; Lyu, A.; Zhang, J.; Wu, M.; Chen, S.; Chen, W.; Li, G.; Yang, L. Optimization of the cultural medium and conditions for production of antifungal substances by Streptomyces platensis 3-10 and evaluation of its efficacy in suppression of clubroot disease (Plasmodiophora brassicae) of oilseed rape. Biol. Control 2016, 101, 59–68.

- Arif, S.; Liaquat, F.; Yang, S.; Shah, I.H.; Zhao, L.; Xiong, X.; Garcia, D.; Zhang, Y. Exogenous inoculation of endophytic bacterium Bacillus cereus suppresses clubroot (Plasmodiophora brassicae) occurrence in pak choi (Brassica campestris sp. chinensis L.). Planta 2021, 253, 25.

- Luo, Y.; Dong, D.; Gou, Z.; Wang, X.; Jiang, H.; Yan, Y.; Wu, C.; Zhou, C. Isolation and characterization of Zhihengliuella aestuarii B18 suppressing clubroot on Brassica juncea var tumida Tsen. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2018, 150, 213–222.

- Ahmed, A.; Munir, S.; He, P.; Li, Y.; He, P.; Yixin, W.; He, Y. Biocontrol arsenals of bacterial endophyte: An imminent triumph against clubroot disease. Microbio.l Res. 2020, 241, 126565.

- Compant, S.; Clément, C.; Sessitsch, A. Plant growth-promoting bacteria in the rhizo- and endosphere of plants: Their role, colonization, mechanisms involved and prospects for utilization. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 669–678.

- Gaiero, J.R.; McCall, C.A.; Thompson, K.A.; Day, N.J.; Best, A.S.; Dunfield, K.E. Inside the root microbiome: Bacterial root endophytes and plant growth promotion. Am. J. Bot. 2013, 100, 1738–1750.

- Lee, S.O.; Choi, G.J.; Choi, Y.H.; Jang, K.S.; Park, D.J.; Kim, C.J.; Kim, J.-C. Isolation and characterization of endophytic actinomycetes from Chinese cabbage roots as antagonists to Plasmodiophora brassicae. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 18, 1741–1746.

- Wang, J.; Huang, Y.; Lin, S.; Liu, F.; Song, Q.; Peng, Y.; Zhao, L. A strain of Streptomyces griseoruber isolated from rhizospheric soil of Chinese cabbage as antagonist to Plasmodiophora brassicae. Ann. Microbiol. 2012, 62, 247–253.

- Wei, L.; Yang, J.; Ahmed, W.; Xiong, X.; Liu, Q.; Huang, Q.; Ji, G. Unraveling the association between metabolic changes in inter-genus and intra-genus bacteria to mitigate clubroot disease of Chinese cabbage. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2424.

- Da Saraiva, A.L.R.F.; Da Bhering, A.S.; Carmo, M.G.F.; Andreote, F.D.; Dias, A.C.; Da Coelho, I.S. Bacterial composition in brassica-cultivated soils with low and high severity of clubroot. J. Phytopathol. 2020, 168, 613–619.

- Thomidis, T.; Michailides, T.J.; Exadaktylou, E. Phoma glomerata (Corda) Wollenw. & Hochapfel a new threat causing cankers on shoots of peach trees in Greece. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2011, 131, 171–178.

- Tran, H.S.; You, M.P.; Lanoiselet, V.; Khan, T.N.; Barbetti, M.J. First Report of Phoma glomerata associated with the Ascochyta blight complex on field pea (Pisum sativum) in Australia. Plant Dis. 2014, 98, 427.

- Comby, M.; Gacoin, M.; Robineau, M.; Rabenoelina, F.; Ptas, S.; Dupont, J.; Profizi, C.; Baillieul, F. Screening of wheat endophytes as biological control agents against Fusarium head blight using two different in vitro tests. Microbiol. Res. 2017, 202, 11–20.

- Sullivan, R.F.; White, J.F. Phoma glomerata as a mycoparasite of powdery mildew. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 425–427.

- Arie, T.; Kobayashi, Y.; Okada, G.; Kono, Y.; Yamaguchi, I. Control of soilborne clubroot disease of cruciferous plants by epoxydon from Phoma glomerata. Plant Pathol. 1998, 47, 743–748.

- Sun, Z.-B.; Li, S.-D.; Ren, Q.; Xu, J.-L.; Lu, X.; Sun, M.-H. Biology and applications of Clonostachys rosea. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 129, 486–495.

- Lahlali, R.; Peng, G. Suppression of clubroot by Clonostachys rosea via antibiosis and induced host resistance. Plant Pathol. 2014, 63, 447–455.

- Sood, M.; Kapoor, D.; Kumar, V.; Sheteiwy, M.S.; Ramakrishnan, M.; Landi, M.; Araniti, F.; Sharma, A. Trichoderma: The “Secrets” of a multitalented biocontrol agent. Plants 2020, 9, 762.

- Alfiky, A.; Weisskopf, L. Deciphering Trichoderma-plant-pathogen interactions for better development of biocontrol applications. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 61.

- Yu, X.-X.; Zhao, Y.-T.; Cheng, J.; Wang, W. Biocontrol effect of Trichoderma harzianum T4 on brassica clubroot and analysis of rhizosphere microbial communities based on T-RFLP. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2015, 25, 1493–1505.

- Li, J.; Philp, J.; Li, J.; Wei, Y.; Li, H.; Yang, K.; Ryder, M.; Toh, R.; Zhou, Y.; Denton, M.D.; et al. Trichoderma harzianum inoculation reduces the incidence of clubroot disease in Chinese cabbage by regulating the rhizosphere microbial community. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1325.

- Card, S.; Johnson, L.; Teasdale, S.; Caradus, J. Deciphering endophyte behaviour: The link between endophyte biology and efficacious biological control agents. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2016, 92, fiw114.

- Van Wees, S.C.M.; van der Ent, S.; Pieterse, C.M.J. Plant immune responses triggered by beneficial microbes. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2008, 11, 443–448.

- Raaijmakers, J.M.; Paulitz, T.C.; Steinberg, C.; Alabouvette, C.; Moënne-Loccoz, Y. The rhizosphere: A playground and battlefield for soilborne pathogens and beneficial microorganisms. Plant Soil 2009, 321, 341–361.

- Narisawa, K.; Tokumasu, S.; Hashiba, T. Suppression of clubroot formation in Chinese cabbage by the root endophytic fungus, Heteroconium chaetospira. Plant Pathol. 1998, 47, 206–210.

- Hashiba, T.; Narisawa, K. The development and endophytic nature of the fungus Heteroconium chaetospira. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2005, 252, 191–196.

- Narisawa, K.; Shimura, M.; Usuki, F.; Fukuhara, S.; Hashiba, T. Effects of pathogen density, soil moisture, and soil pH on biological control of clubroot in Chinese cabbage by Heteroconium chaetospira. Plant Dis. 2005, 89, 285–290.

- Lahlali, R.; McGregor, L.; Song, T.; Gossen, B.D.; Narisawa, K.; Peng, G. Heteroconium chaetospira induces resistance to clubroot via upregulation of host genes involved in jasmonic acid, ethylene, and auxin biosynthesis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94144.

- Jäschke, D.; Dugassa-Gobena, D.; Karlovsky, P.; Vidal, S.; Ludwig-Müller, J. Suppression of clubroot (Plasmodiophora brassicae) development in Arabidopsis thaliana by the endophytic fungus Acremonium alternatum. Plant Pathol. 2010, 59, 100–111.

- Baldrian, P. The known and the unknown in soil microbial ecology. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2019, 95, fiz005.

- Jeger, M.; Beresford, R.; Bock, C.; Brown, N.; Fox, A.; Newton, A.; Vicent, A.; Xu, X.; Yuen, J. Global challenges facing plant pathology: Multidisciplinary approaches to meet the food security and environmental challenges in the mid-twenty-first century. CABI Agric. Biosci. 2021, 2, 1–18.

- Sessitsch, A.; Mitter, B. 21st century agriculture: Integration of plant microbiomes for improved crop production and food security. Microb. Biotechnol. 2015, 8, 32–33.

- Raaijmakers, J.M.; Mazzola, M. Soil immune responses. Science 2016, 352, 1392–1393.

- Mueller, U.G.; Sachs, J.L. Engineering microbiomes to improve plant and animal health. Trends Microbiol. 2015, 23, 606–617.

- Mendes, R.; Garbeva, P.; Raaijmakers, J.M. The rhizosphere microbiome: Significance of plant beneficial, plant pathogenic, and human pathogenic microorganisms. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 37, 634–663.

- Rybakova, D.; Mancinelli, R.; Wikström, M.; Birch-Jensen, A.-S.; Postma, J.; Ehlers, R.-U.; Goertz, S.; Berg, G. The structure of the Brassica napus seed microbiome is cultivar-dependent and affects the interactions of symbionts and pathogens. Microbiome 2017, 5, 104.

- Verbon, E.H.; Liberman, L.M. Beneficial microbes affect endogenous mechanisms controlling root development. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 218–229.

- Lebreton, L.; Guillerm-Erckelboudt, A.-Y.; Gazengel, K.; Linglin, J.; Ourry, M.; Glory, P.; Sarniguet, A.; Daval, S.; Manzanares-Dauleux, M.J.; Mougel, C. Temporal dynamics of bacterial and fungal communities during the infection of Brassica rapa roots by the protist Plasmodiophora brassicae. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0204195.

- Niu, B.; Wang, W.; Yuan, Z.; Sederoff, R.R.; Sederoff, H.; Chiang, V.L.; Borriss, R. Microbial interactions within multiple-strain biological control agents impact soil-borne plant disease. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 585404.