You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hassan Shahraki | + 4601 word(s) | 4601 | 2022-03-16 04:04:28 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | -19 word(s) | 4582 | 2022-03-24 02:34:01 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Shahraki, H. Three-Dimensional Paradigm of Rural Prosperity. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20923 (accessed on 23 December 2025).

Shahraki H. Three-Dimensional Paradigm of Rural Prosperity. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20923. Accessed December 23, 2025.

Shahraki, Hassan. "Three-Dimensional Paradigm of Rural Prosperity" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20923 (accessed December 23, 2025).

Shahraki, H. (2022, March 23). Three-Dimensional Paradigm of Rural Prosperity. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20923

Shahraki, Hassan. "Three-Dimensional Paradigm of Rural Prosperity." Encyclopedia. Web. 23 March, 2022.

Copy Citation

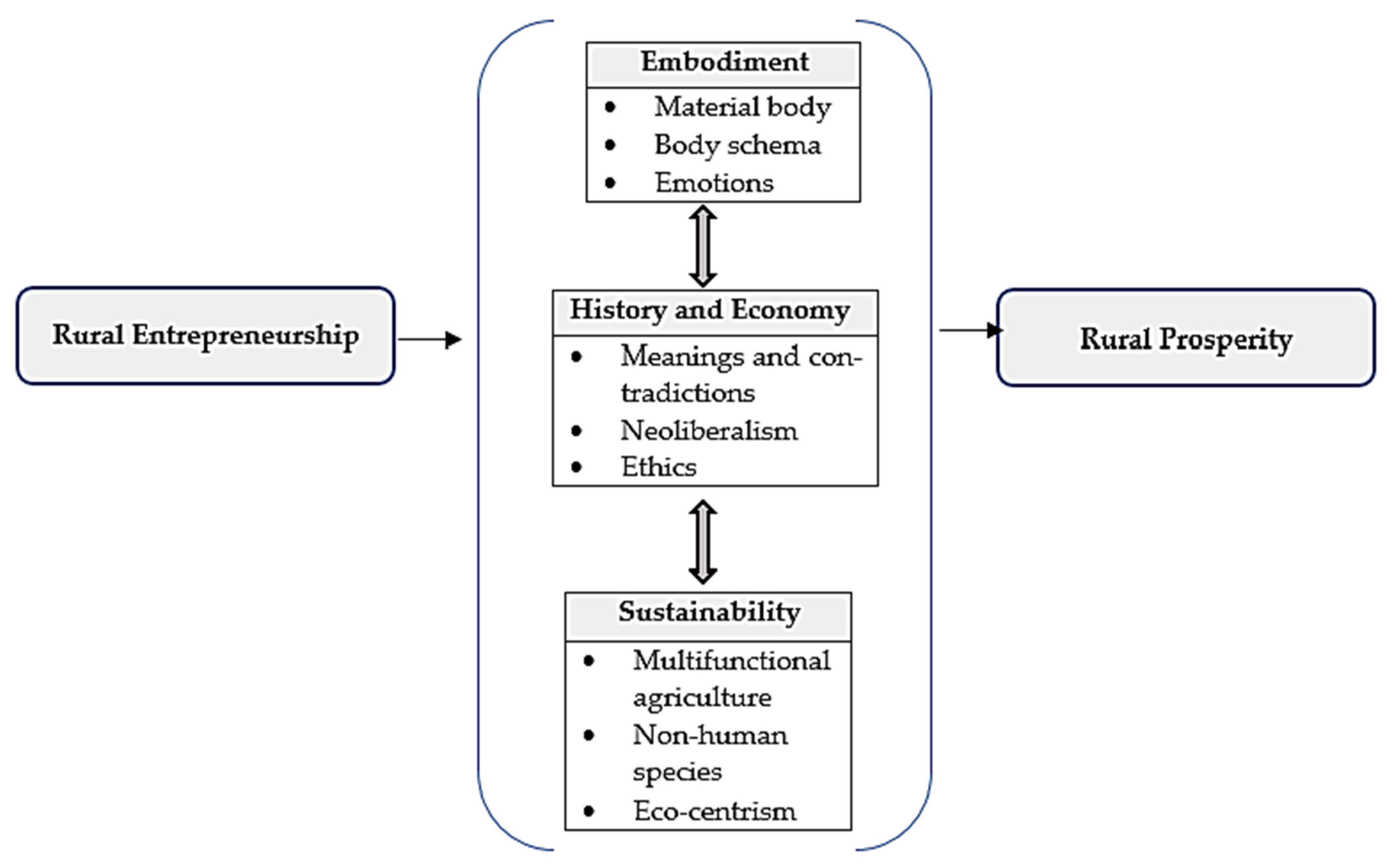

The paradigm of rural prosperity on three pillars of analysis and explanation: (a) rural embodiment, (b) neoliberalism, and (c) concept of sustainability.

entrepreneurship

rural prosperity

neoliberalism

embodiment

sustainability

rural development

postdevelopment

Aram Ziai

Campbell Jones

André Spicer

1. First Pillar: Rural Embodiment (Embodiment, Body Schema, and Emotions)

In short, the purpose of the first pillar is to include embodiment in three areas: (a) the physical and material aspects of the body, (b) body schema, and (c) the emotional status of man. Figure 1 shows this pillar. Embodiment is important, since individuals’ awareness is rooted and not separated from their bodies or embodiments [1]. Embodiment is a missing element in the entrepreneurship process. Therefore, the purpose of this pillar is to return the embodiment to the entrepreneurship process. The main argument is that, owing to Descartes’ dichotomy of mind–body domination in the entrepreneurship literature, particularly in the discovery school, the basis of both concept of awareness and concept of creativity has been completely neglected in the entrepreneurship literature. Awareness does not only mean discovering the shortcomings of the “market”, and creativity does not only mean a “new composition” in the sources of production; rather, they are the product of organizing a new cognitive and embodied way of dealing with international developments (for example, climate change, globalization, and feminism), national (such as privatization, government employment policies, and changes in people’s tastes), and local developments (immigration, agricultural hardship, prevalence of industry in the rural areas, urbanization, and natural disasters). Resilience to climate change and high temperatures, influence of feminism in rural areas, fluctuations in demand and taste, and difficulty of farming all have body and embodiment implications. Entrepreneurship discourse should be able to reveal its association with these categories. To transform entrepreneurship into a phenomenon considering the body more seriously, one should speak of embodiment as a resource for challenging the existing order. Such a process requires the creation of a kind of comprehensive awareness of the surrounding world. Moreover, awareness is not very meaningful without a bodily foundation, as according to an Iranian proverb, “a healthy mind is in a healthy body”.

Reviewing rural entrepreneurship and its involvement within political and economic struggles requires adopting new attitudes toward the body and embodiment and understanding that the body is both a medium to express the tendencies and attitudes of society and a creative and vibrant source of new perceptions. If people accept that rural entrepreneurship is closely associated with multi-functional agriculture [2], then the transformation of entrepreneurship into multi-functional agriculture requires fundamental changes in bodily perceptions intertwined with masculinity and heterosexuality and the affirmation of a kind of bodily comfort, rather than pressure on the body by a tough man. Here, embodiment, or real bodies will be discussed [3]. Even the human development index (HDI) does not explicitly mention human physicality or embodiment. The inclusion of embodiment in the entrepreneurship process requires a transition to a different understanding of rural embodiment. In hermeneutical realism, the rural body is not a hard-working, masculine, and oppressed being that nourishes other bodies but needs no nutrition itself. However, it is an embodiment living in the heart of constructs and cultural and social factors, while having materiality and physicality and its understanding and function. In this sense, entrepreneurial alertness, prediction, creativity, and ability can all be summarized and analyzed in a cognitive and psychomotor set. The negotiable and constructivist discourse of entrepreneurship must pay attention to this body schema, which is rooted in the rural environment crossing geographical and physical boundaries. Here, the body schema is used in a sense similar to Shilling [1] and means physical topography, as well as the experience of living in a social environment. In this sense, body schema means the inclusion of a geographical or physical body within a figurative space. For example, if farmers want to be diversified and multi-occupational, they must reorganize and re-evaluate their mental perception—through attitudes and perceptions—and life experience—through body schema-concerning rural space and agricultural work. Another example is climate change, which raises both the need to pay attention to the body—and society as a whole collective entity—and the multiplicity in the rural. The questions to be answered here is how resilient the body is to climate change and high temperatures, particularly in rural areas with low rates of underdevelopment, and is it still possible to continue agriculture as an old and long-lasting means of livelihood in warmer and drier conditions? Another aspect of the inclusion of the body and embodiment in the entrepreneurship process is related to the emotional aspect of entrepreneurship, which is less addressed. Most of the personality traits mentioned in psychological approaches for entrepreneurs, such as risk-taking, confidence, autonomy, and creativity, indicate the human/entrepreneur emotional aspects. “Resistance” to innovation, as well as the anxiety of losing money caused by incorrect “predictions” during the entrepreneurship process, has both embodied and emotional aspects. The word “prosperity” has positive psychological connotations, and thus it has emotional aspects. Embodied gymnastics or identity-building bio-agency requires a kind of emotional outburst in the body to become an entrepreneur and overcome power relations at both national and local levels seeking to maintain the status quo. In this regard, David Goss’ study [4] provides a new analysis of entrepreneurship based on Burrell and Morgan’s metatheory. Goss argues that Schumpeter’s insights into the sociology of entrepreneurship emphasizing individuals’ will and motivation contain key elements and variables, such as social interaction and emotions. The dual meanings—both psychological and social—represented by Goss as Schumpeter’s traits for entrepreneurs are well developed in the form of Randall Collins’s interaction ritual theory (IRT) [5]. The core of the interaction ritual theory is emotional energy. Collins argues that the macro-level order-producing mechanisms in classical sociology (including power, ideology, values, and norms) are based on emotions. Collins’s view can be expanded to include the concept of dissatisfaction with erroneous predictions in the entrepreneurship process and its relation to depression. Therefore, the body (and emotions) is another embodied aspect, which has been overlooked in the entrepreneurship literature. In addition, some studies [6] revealed that high levels of depression and isolation were evident in entrepreneurs who were unable to sell their products due to a lack of proper marketing. Here, people encounter a kind of entrepreneurial body, but one isolated and cut off from others as well as space [7], which is increasingly moving toward lack of desire and silence. Generally, it can be stated that the need to address embodiment, particularly in rural areas with a deeper connection with nature, is twofold. Hence, rural entrepreneurship must be a kind of link between the body and the environment. Hence, a naturalistic or nature-friendly body can be considered a body not satisfying its desires in exchange for harm to nature.

Figure 1. An integrated model for rural prosperity.

2. Second Pillar: From Capitalist Individualism and Profit Maximization to the Moral Economy

The purpose of this pillar is to present a brief history of entrepreneurship and neoliberalism, to emphasize the inclusion of ethics in the general fabric of the society, to move beyond methodological individualism intertwined in the entrepreneurship literature, particularly in Schumpeter’s thought, the rejection of the maximalist assumption in neoliberal economics, and to regard it as a particular kind of freedom emphasized in both hermeneutical realism and Jones and Spicer’s views. In the following, the connection between the history of neoliberalism and the history of entrepreneurship is discussed. Furthermore, it is revealed that there is no significant relationship between entrepreneurship, which is rooted in the Austrian school, and Adam Smith’s classical economics. Thus, with the failure of the positivist orthodoxy of the 1950s [8], leaving the modernization school behind in the late 1950s, this school and theoretical transition to the dependency theory of the 1960s and 1970s were unsuccessful. It did not work in any country except Tanzania. With new laws in the United States as well as new regulations and privatization in Britain, the capital is free to move across borders, and no government (let alone a small, poor government) can pursue an economic policy against capitalists. Economic planning, welfare systems, and monetary and tax policies are all effectively controlled by capital markets. Government and large-scale post-war development projects have been replaced by small- and mid-sized enterprises (SMEs) run by maximizer individuals. Entrepreneurship, which is inherently a model of capitalist development, has been raised since the 1900s to bridge the gap between the neoclassical theory in economics and the social approach. It became a priority in free market-based economic policies in the early 1980s and with a slight delay in a country such as Iran in the 1990s. Such policies increasingly lead to neoliberalism and superiority of the financial sector overproduction. A study [9] on the history of development in India reveals that how Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) relinquished its monopoly on planning for India’s future with the economic liberalization in 1991. Designing what became known as entrepreneurial citizenship, and following Indian immigrants working in Silicon Valley, it requested all political parties, media, and business lobbies to set up startup villages and to promote a “patent” culture. In Iran, for more than two decades, all governments have insisted on entrepreneurship as a “sacred and obvious aspect” [6]. Iran is a country that has embraced and acted on the structural adjustment policies of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund since the 1990s when Hashemi Rafsanjani took office. A study in Iran indicates how government-based—actually a regulating government operating in an economy between a state-owned economy and a free market—entrepreneurship discourse is influenced by capitalist relations, such as public expropriation, commodification of nature, and commodification of labor. Moreover, the shortcomings in capital accumulation, the dominance of unproductive activities over productive, the commercial capital over the domestic producers, and the capital outflows (capital flight) over the capital inflow (investment and accumulation) disrupt the capitalist process. These cases cause lending to become a source of rentiership and therefore, in both urban and rural areas, it has led to a rival discourse that relies on fixing and has goals that contradict the development discourse. Schumpeter’s views promote a kind of methodological individualism intertwined with the Austrian school [10]. Schumpeter’s departure from Walras’ concept of stationary economy is evident in The Theory of Economic Development (1911) and through the concept of business cycles [11]. After the publication of the second volume of Theory of Economic Development in 1926 and the book Business Cycles in 1939, Schumpeter took a more limited and systematic position on entrepreneurship, and, as Swedberg puts it, he moved from a Dionysian to an Apollonian position. Then, it has been argued that Schumpeter also seeks some forms of capitalist entrepreneurship development. Considering the issue of the priority and least priority of entrepreneurship and the basic economic system, along with capitalism as the driving force of economic development, it has long been assumed that economics has little to offer in terms of entrepreneurship [10][11][12][13]. Most of the dominant economists of the 18th and 19th centuries, such as Cantillon, Smith, and Say, never considered entrepreneurship as a source of change, development, and progress [14]. However, some Austrian economists have such a broad view of the entrepreneur that they sometimes use the term “entrepreneur” simply because profit or income is associated with risk or uncertainty and consider industrialists and factory owners as entrepreneurs. Even Ludwig Von Mises suggested that entrepreneurship might lose money due to misprediction of consumer needs, thereby creating obstacles to economic development and finally wasting resources. There are subtle differences between thinkers such as Mises and Schumpeter and Krizner and Hayek. However, they have all sought to implement entrepreneurship as a strategy to advance the capitalist economy [12]. Therefore, even if entrepreneurship is related to development, it is more of a complementary strategy aiming at creating employment for those who are lagging behind the development in rural areas, while considering industrial and service sectors. It is worth noting that in the strategy of modernity, a form of “integrated rural development” as a kind of intervention and comprehensive attack on passive rural environments and cultures to manage and control them. However, in entrepreneurship, there is the same attack, not from the “developer”, but the “entrepreneur”. Here, the entrepreneur is introduced as someone competing with other entrepreneurs to obtain facilities from banks. He/she only seeks to maximize his/her own or corporate profits in the globalized and neoliberal economy dominated by transnational corporations. Entrepreneurship can be the evil twin of development in the sense that it disrupts the development or causes it to be forgotten. Therefore, it is highly important to be familiar with the history of entrepreneurship while deconstructing its language and conceptual contradictions in the entrepreneurial discourse. This is emphasized by both the skeptical post-development and the critical theory proposed by Jones and Spicer. Accordingly, the purpose of the second pillar is to incorporate inclinations, values, and identities into the notion of maximalism, as one of the foundations of entrepreneurial thinking. Kean Birch [14], a moderate and important researcher and critic of neoliberalism, argues that when people become entrepreneurs under the influence of neoliberalism, rentiership is further increased in the economy. In Birch’s view (Ibid: 131), entrepreneurship is highly correlated with neoliberalism. Birch (Ibid: 30) also states that at least eight important schools of thought are evident in the intellectual history of neoliberalism, the most important of which are the schools of Chicago and Austria. However, they all have common features, such as monopoly of elites through corporations and holdings, market essentialism, financialization, deregulation, reduction or cessation of public service austerity, and prevalence of rentiership and corruption, which can be classified under entrepreneurship. All of these features can be outlined to some degree in Iran’s economy. For example, Ziai [15] mentions the destructive impact of foundations on Iran’s economy, giving a demagogic and reactionary character to the development discourse of the country, while most of these foundations control a significant part of Iran’s economy and attempt to escape the tax. Earlier in this regard, people mentioned the prevalence of corruption in the lending discourse of entrepreneurship policies in Iran. Today’s crisis of the Tehran Stock Exchange is due to the undisputed dominance of legal entities (monopolies) over Iran’s monetary and banking economy. Essentialism in culture, influenced by a political–ideological structure, has paved the way for entrepreneurial essentialism. Here, entrepreneurs are referred to as holy men driving the economy alone. Of the USD 1.5 billion credit from the National Development Fund for rural development and job creation in rural areas in September 2018, approximately USD 22 million was allocated to Sistan and Baluchestan Province—one of the most deprived provinces in the country [16]. However, of the 9285 villages in the province, 2732 (approximately 30%) have been deserted during the recent 15-year drought. This indicates the prevalence of hegemonic and essentialist discourse of entrepreneurship while not critically considering it. Entrepreneurship has progressed simultaneously with backwardness in development. Ziai emphasizes cultural essentialism in skeptical post-development and rejects it. Reliance on the contradictions is a component of Jones and Spicer’s critical theory and skeptical post-development theory. Furthermore, the concept of living, which is the product of the mind’s intention toward the world around it (humans, plants, animals, and the earth all play a role in inhabitants’ lives), is not possible except by abandoning (economic and sociocultural) epistemological essentialism. Abazari [17], a prominent sociologist in Iran, criticizes the Persian translation of the entrepreneur and points to the entrepreneur’s rent-seeking characteristics from a more radical position than Birch holds. He blames the implementation of Hayek–Friedman policies as one of the causes of the 2008 financial crisis. Like Abazari, Simon Springer [18] considers neoliberalism from a critical perspective and presents the razor-sharp critique from Foucault’s viewpoint assuming that neoliberalism is a discourse. His prose skillfully fluctuates between academic and literary styles and embraces both. Both Abazari’s paper and Springer’s critique suffer from the flaw the same as Birch when criticizing Dardot and Laval’s book The New Way of the World: the lack of empirical evidence for the claims made. Springer’s analysis is interesting, since it relates privatization and entrepreneurialism to the imperialist goals of metropolitan countries in places such as Afghanistan, their geographical reconstruction, and the creation of uneven development in those countries. Neoliberalism attempts to restore power to weak countries such as Afghanistan, which have an open economic space, with the slogan of geographical reconstruction and the logic of securitization. “Dirty work” and “regulatory power” of neoliberalism will only be revealed by a precise deconstruction of its discourse and interpretation of its meaning (Ibid: 73). This analysis seeks to explore the meaning of both neoliberalism and entrepreneurship. Personal interest, which is the ultimate goal of business activities, is at the core of Schumpeter’s views and requires serious attention. Adam Smith’s pseudo-problem and the contradiction of his views on “Wealth of Nations and the Theory of Moral Sentiments” show how economics cuts off the moral system, particularly in the Austrian school, and emphasizes entrepreneurship to put the latter first. Therefore, based on hermeneutical realism, a different orientation (a component of life) should be considered toward existence (capitalist-based entrepreneurship), which is created through the exercise of the freedom right of economic actors (agency) in the rural arena. This agency-based existence is born of the integration of the moral system (society) with a profit-oriented economy. The intervention of ethics does not mean the establishment of any kind of individual ethics (micro-moral system), such as the right to own property, the right to accumulate and transfer wealth, the establishment and registration of companies—or the concentration of morality in an institution called the state. However, as stated in the first principle of Spicer and Jones’s theory, it is a new representation of the entanglement of ethics with entrepreneurship, rural, and rurality, which can be achieved by creating a macro-moral system. The debate is over the distribution of ethics in the general fabric of the economic system. The ultimate goal here is to prevent the transformation of human beings to enterprises or investment opportunities through the ethnics of the social fabric and to restore identity and emotions to the homo economicus, who is an entrepreneur of the self. Instead of an omnipotent market, one must speak of omnipotent ethics and release social relations from the predicament of corporate bondage. The moral system, either micro or macro, can be constrained by government policies in line with market-oriented liberalism, through pressure from institutions such as the International Monetary Fund or strong lobbies, such as pharmaceutical companies. On the contrary, it can be expanded through voluntary environmental standards by companies, government policies, and NGO activists, and the shift in consumption patterns to value consumption to support weak and underdeveloped producers. In fact, what is called “fair trade” can be extended from handicrafts to agricultural products. Consumers can easily support fair trade practices and policies. The element of living in hermeneutical realism is based on the emergence of action toward the surrounding world, an action that is reflected by ethics according to the present work. The modern German philosopher Kant interprets ethics as a kind of practical intellect. The normal integration of ethics into the capitalist economy is the new intention of rural actors toward the figurative space of the rural. The figurative space will be based on dual hegemonic and colonial constructs existing in both the entrepreneurship literature, such as the creative and innovative entrepreneur versus the ordinary farmer, and the rural development literature, such as the civilized versus the savage. In short, the second pillar includes (a) a description of the history and scrutiny in the meaning of entrepreneurship and rurality, (b) an explanation of the neoliberal aspects of entrepreneurship through a moderate critique of neoliberalism, and (c) inclusion of an ethical system in the entrepreneurial process.

3. Third Pillar: Sustainability and Return to Nature Itself (The Right to Live for the Rural Ecosystem)

This section emphasizes that entrepreneurship must first be transformed into multi-functional agriculture, then to the protection of animals and plants rights, and finally to the preservation of space (ecosystem) in its figurative sense, or it is presented in the form of these phenomena. Rural entrepreneurship is the evidence of structural changes in rural communities and agriculture. Some of these changes are reflective and act as a response to changes in urban environments, markets, and government policies, while some are inherent in rural communities and environments. The changes encompass trade liberalization, market changes, transformations, biotechnological advances, privatization, climate and ecological changes, and alterations in agricultural customers’ tastes. Therefore, diversification of agricultural activities, by considering the agricultural–climatic and socioeconomic characteristics of the target areas, production of higher value-added products and their export, and reduction of production waste, has become the hallmark of rural entrepreneurship. The changes have also profoundly affected the EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), since the move from productive agriculture to market-focused agriculture and the support of sustainable and eco-friendly agriculture are the key elements of this policy. The EU Agricultural Policy reforms have put farmers in a position where they are expected to have their farm as a company to develop as an entrepreneur. However, in Ziai’s skeptical post-development theory, the view of the rural is like a territorial community. This territorial community acknowledges the fusion of urban and rural areas but always attempts to maintain its boundaries with the outside and to strengthen an ecological awareness. This maintenance of boundaries is a sign of the element of understanding in the hermeneutical realism model. One of the activities exemplifying the conceptualization of a territorial community is multi-functional agriculture. Multi-functional agriculture in adapting the element of understanding and, unlike entrepreneurship or in completing it, can be a sign of transition from one thing to another and the awareness of this transition. The changes range from traditional agriculture and cultivation patterns to service or industrial production, from productivism to post-productivism, and from ideological essentialism to culture and constructivist rurality. Ziai’s skeptical post-development model emphasizes the importance of the concept of constructivist culture, while Jones and Spicer’s conceptual model presents different interpretations or representations of the concept of entrepreneurship. These conceptual representations are developed in the hermeneutical realism model and are described in the form of a figurative space. Many European farmers are now engaged in multi-functional farming. According to Eurostat [19], in 2007, 10% of EU farmers were involved in one or more non-agricultural income-generating activities. Finland ranked first with 28%, followed by France with 24% and Sweden and the United Kingdom with 23%. In the Netherlands, approximately 19% of farmers were engaged in one or more profitable activities other than farming. The multi-functional agriculture concept, following the theoretical models presented, is based on a kind of rural and agricultural hermeneutics. In other words, it does not limit rurality to agriculture and emphasizes the importance of the construction process through language and time. Multi-functional agriculture in this sense contains semantic (discourse) and practical (procedural) implications from productivism to post-productivism. Multi-functional agriculture contains the important semantic and cultural element of identity, the element encompassing diverse orientations of rural people toward space, career, and gender. In this sense, identity can act as a drive from being to living and act on understanding in the hermeneutical realism model, and turn an ordinary farmer into an entrepreneur and then into a multi-functional or a multi-skilled person. Multi-functionality is a process examining both tradition and modernity by relying on individual agency. From this perspective, functional agriculture rejects the idea of unity and discourse order in rural and rurality. In the skeptical post-development theory, the transition from ideology to nature is explicitly mentioned in the discussion of development. This transition should first transform rural entrepreneurship into a phenomenon aiming at rewriting entrepreneurship and considering it in a new way. Nayeri [20] regards this phenomenon as the product of a social revolution. In designing his plan for a kind of eco-centric socialism, Nayeri points out that the domestication of animals and plants is the basis of agricultural communities and modern capitalist civilization. However, this process of domestication has caused at least half of the land and sea to be taken from the wildlife, the share that must be returned to it. Nayeri adds that systematic and complete domestication has caused fatal damage to plant and animal species. Moreover, the breeding, fattening, cultivation, and artificial insemination of only a dozen crops (bananas, barley, corn, cassava, potatoes, rice, sorghum, soybeans, sugar beets, sugarcane, sweet potatoes, and wheat) and only five large domestic animals (cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, and horses) destroy more than 70% of wild species. This process paved the way for the beginning of anthropocentric sixth extinction at a rate of more than 1000 times the rate of natural extinction. Therefore, any conceptualization of the central component of the rural entrepreneurship process, i.e., the opportunity component, must be conditional on the preservation of wild species and the rethinking of the dual wild–civilized structure. This conceptualization has also been emphasized by Rosenqvist [21]. Thus, the notion of human victimization should be transmitted to the notion of plant and animal victimization. Rural entrepreneurship should be able to soften human–animal relationships. Lefebvre, by introducing the concept of “Right to the City”, proposed a happy coexistence between man and animal, and the extension of some rights from man to animal for rebuilding the human–animal relationship and strengthening multi-functional agriculture. In this sense, the traditional farmer is changed to someone who protects public goods and genetic resources and receives a salary from environmental institutions. Therefore, the late concept of “Zoopolis” [22], which indicates granting citizenship rights to animals, should be considered in reforming the discourse and practice of rural entrepreneurship. Rethinking and critique of rural entrepreneurship can also be a prelude to provide a new context for research as interrupting or modifying discourse and practices related to the concept of “growth” or “developmentalism”. This requires a fundamental transformation of the relationship between man and nature. To better explain the transition from beings to the whole ecosystem or biosphere, people must take a broader look. In this regard, it should be emphasized that the concept of opportunity, which is considered a key component in the entrepreneurial process [23], should be defined and realized in completion and adaptation to nature. Thus, people witness the transition from the idea of domination of nature to the happy coexistence and harmony with nature. In this regard, Nayeri [20] explains that our forager ancestors saw themselves as a part of the surrounding world, so that some cultures regarded humans, animals, and plants as agents related to each other by blood ties and common ancestors. According to Nayeri, this is an eco-centric worldview, it should dominate the discourse and practice of rural entrepreneurship. In parallel with the expression of the concept of freedom for man, freedom can also be extended to human and animal species to challenge the dominant discourse(s) and structures and the analysis of the occasional and inevitable submission of man to objective (laws) and mental structures (language and its dichotomies). Hence, one can reach a discourse or at least a climate of opinion to critique homo-centrism and speciesism. Given the setback at the Cop26 Glasgow Summit on the Paris Agreement, which emphasizes only a “gradual” rather than an “abrupt” reduction in greenhouse gases and fossil fuels, especially coal, Nayeri’s eco-centric focus should be considered in entrepreneurial interventions. Briefly, the third pillar includes (a) explaining the relationship between rural entrepreneurship and multi-functional agriculture, (b) transitioning to the concept of Zoopolis and proposing the concept of citizenship for plants and animals, and (c) focusing on ecocentrism and its implications for rural entrepreneurship.

References

- Shilling, C. The Body and Social Theory; Sage: London, UK, 2012.

- Shahraki, H.; Heydari, E. Rethinking rural entrepreneurship in the era of globalization: Some observations from Iran. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2019, 9, 42.

- Evans, M.; Lee, E. Real Bodies: A Sociological Introduction; Palgrave: New York, NY, USA, 2002.

- Goss, D. Schumpeter’s Legacy? Interaction and emotions in the sociology of entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2005, 29, 205–218.

- Collins, R. Interaction Ritual Chains; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2004.

- Shahraki, H.; Sarani, V. Development and its Evil Twin: The Situational Analysis of Rural Entrepreneurship in Sistan Region. Community Dev. (Rural. Urban Communities) 2019, 11, 173–196.

- Frank, A. The Wounded Storyteller: Body, Illness, and Ethics; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1997.

- Leys, C. The Rise and Fall of Development Theory. In The Anthropology of Development and Globalization: From Classical Political Economy to Contemporary Neoliberalism; Edelman, M., Haugerud, A., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, USA, 2005; pp. 109–125.

- Irani, L. Chasing Innovation: Making Entrepreneurial Citizens in Modern India; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2019.

- Smelser, N.J.; Swedberg, R. (Eds.) The Handbook of Economic Sociology; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005.

- Swedberg, R. The Social Science View of Entrepreneurship: Introduction and Practical Applications; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000.

- Knudson, T.; Swedberg, R. Capitalist Entrepreneurship: Making Profit through the Unmaking of Economic Orders. Capital. Soc. 2009, 4, 3.

- Licht, A.; Siegel, J.I. The Social Dimensions of Entrepreneurship; Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya, Kanfe Nesharim St.: Herzliya, Israel, 2010.

- Birch, K. A Research Agenda for Neoliberalism; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2017.

- Ziai, A. Gharbzadegi in Iran: A Reactionary Alternative to ‘Development’? Development 2019, 62, 160–166.

- Irna. Available online: https://www.irna.ir (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- Abazari, Y. The Market fundamentalism. Mehrneme 2013, 31, 160–192.

- Springer, S. The Discourse of Neoliberalism: An Anatomy of a Powerful Idea; Rowman and Littlefield: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2016.

- Ec.europa. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat (accessed on 5 October 2021).

- Nayeri, K. The Crisis of Civilization and How to Resolve It, Translated to Persian by Hooman Kasebi. 2018. Available online: https://Pecritique.com (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- Rosenqvist, O. Deconstruction and hermeneutical space as keys to understanding the rural. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 75, 132–142.

- Donaldson, S.; Kymlicka, W. Zoopolis: A Political Theory of Animal Rights; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011.

- Dempster, G.M. Why (a theory of) Opportunity Matters: Refining the Austrian view of entrepreneurial discovery. Q. J. Austrian Econ. 2020, 23, 427–461.

More

Information

Subjects:

Development Studies

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

821

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

24 Mar 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No