You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Isaura Simoes | + 2237 word(s) | 2237 | 2022-02-24 07:05:54 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | -11 word(s) | 2226 | 2022-03-21 02:37:26 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Simoes, I. Moonlighting in Rickettsiales. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20751 (accessed on 20 December 2025).

Simoes I. Moonlighting in Rickettsiales. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20751. Accessed December 20, 2025.

Simoes, Isaura. "Moonlighting in Rickettsiales" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20751 (accessed December 20, 2025).

Simoes, I. (2022, March 18). Moonlighting in Rickettsiales. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20751

Simoes, Isaura. "Moonlighting in Rickettsiales." Encyclopedia. Web. 18 March, 2022.

Copy Citation

Rickettsiales comprise a diverse and expanding list of vector-borne obligate intra-cellular Gram-negative bacteria that include many animal and human pathogens as well as non-pathogens. Members of Rickettsiales are characterized by small genomes, with sizes ranging between 0.8 and 2.5 Mbp, and the number of hypothetical proteins varying from 88 to 536.

Rickettsiales

Anaplasma spp.

Ehrlichia spp.

Orientia spp.

Moonlighting

Rickettsia spp.

1. Introduction

Rickettsiales comprise a diverse and expanding list of vector-borne obligate intra-cellular Gram-negative bacteria that include many animal and human pathogens as well as non-pathogens. Members of Rickettsiales are characterized by small genomes, with sizes ranging between 0.8 and 2.5 Mbp, and the number of hypothetical proteins varying from 88 to 536 (recently reviewed in [1]). Rickettsiales organisms are globally widespread, and their geographical distribution is mostly defined by both vector and natural host constraints. A rise in incidence and resurgence patterns of human diseases caused by these vector-borne pathogens has been increasingly recognized, resulting from the impact of climate and social changes on the distribution and abundance of the arthropod vectors and associated pathogens. For example, human granulocytic anaplasmosis caused by Anaplasma phagocytophilum and transmitted by the tick Ixodes scapularis is among the three most important vector-borne diseases in the United States (U.S.), with data showing a ~12-fold increase in reported human cases from 2010–2018 [2]. Also, it is increasingly being reported in Asia and several Central/Northern Europe where the distribution of Anaplasma and its vector Ixodes ricinus is increasing both in latitude and altitude [3][4]. Likewise, the increased incidence of human ehrlichiosis in the U.S. has also been associated with a geographical expansion of the tick Amblyomma americanum and E. chaffeensis to northern regions [5]. Scrub typhus is currently recognized to have a wider presence beyond the endemic areas of the tropical Asia-Pacific region and northern Australia, with cases emerging in South America, the Middle East, and Africa. It is estimated that approximately 1 million cases of scrub typhus are reported every year, resulting in a significant and increasing burden in endemic areas [6][7]. Interestingly, although it is known that chigger trombiculid mites (Leptotrombidium spp.) are the vector for Orientia tsutsugamushi, the nature of the vector(s) of other emerging Orientia species in the Western Hemisphere is still not clear [6]. Among rickettsial diseases, there is a growing concern about the globally increasing incidence of Spotted fever group rickettsioses (SFR); not only the most severe forms of these diseases but, particularly, milder forms caused by new species of rickettsiae [8][9]. For example, the incidence of SFR in the U.S. has significantly increased over the last two decades, from 1.7 to 19.2 cases per million persons from 2000 to 2017 [10][11]. Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF), caused by R. rickettsii through a bite of Dermacentor variabilis, D. andersoni, or the brown dog tick (Rhipicephalus sanguineus), is still the most severe and fatal of the SFR. Recent outbreaks of RMSF in Mexico (2004–2016) resulted in case fatality rates of ~29–30% (higher in children <10), representing an expanding public health problem [12]. Mediterranean spotted fever, caused by R. conorii (and transmitted by R. sanguineus) is endemic to the Mediterranean basin and considered the most prevalent rickettsial disease in Europe [13]. There is also a growing concern in Europe about the increasing incidence of milder rickettsioses, such as tick (Dermacentor)-borne lymphadenopathy/Dermacentor-borne necrotic erythema and lymphadenopathy (TIBOLA/DEBONEL) syndrome [14], and the epidemiological importance of SFRs in Africa is increasingly recognized [15]. Importantly, rickettsial diseases transmitted by fleas like murine typhus and flea-borne spotted fever (caused by R. typhi and R. felis, respectively) occur worldwide, and emergence patterns for both are evident in many regions of the globe [16][17]. Other R. felis-like organisms, like R. asembonensis, follow identical geographical patterns as those of R. felis and have been associated with other arthropods, raising the interest in understanding in detail their potential as a pathogen [18].

The drastic increase in the identification of new Rickettsiales species whose pathogenicity to humans is still uncertain, increased probabilities of Rickettsiales-carrying arthropods to encounter human hosts, the high mortality rates of some of these diseases if left untreated, the fact that these organisms are not susceptible to many classes of antibiotics, and the absence of approved vaccines bolsters the need to continue understanding the pathogenesis of these obligate pathogens and identifying new therapeutic targets for these diseases [9][19].

2. Bacterial Moonlight Proteins

Moonlight proteins comprise a subset of proteins that present more than one physiologically relevant function that is not due to gene fusion, multiple RNA splice variants, or pleiotropic effects [20]. Another characteristic of these proteins is that the functions exerted are independent of each other, meaning that the inactivation of one function must not affect the others. According to MoonProt 3.0 [21] (MoonProt 3.0. Available online http://moonlightingproteins.org (accessed on 5 February 2022) and MultitaskProtDB-II [22] (MultitaskProtDB-II. Available online: http://wallace.uab.es/multitaskII accessed on 5 February 2022), two repositories where these activities are being compiled, there are over 500 annotated moonlight/multitasking proteins which are extraordinarily diverse and involved in a large array of biological functions. Since many of the proteins have evolved to exert various functions, there is not a shared sequence or structural feature that can be used to foresee the moonlighting activity, being mainly discovered by serendipity, proteomics, and yeast two-hybrid assays [23]. Additionally, if a protein is homologous to a moonlighting/multitasking protein, it does not imply that it presents the same functions since it can exert one, both, or none of the moonlighting protein functions [24]. Due to this, it is difficult to identify and predict if a protein presents moonlight activity. However, bioinformatics approaches have been in development to aid in this process [25][26][27].

Moonlight proteins are present in several organisms, including animals, plants, yeasts, bacteria, and viruses [24][28]. These proteins have been gaining attention by playing important roles in autoimmune diseases, diabetes, and cancer [29]. In bacteria, moonlighting proteins are present in both pathogenic and commensal bacteria, and many of these proteins are highly conserved in these organisms [30]. Importantly, 25% of moonlight proteins are classified as virulence factors and may contribute to bacterial pathogenesis and virulence [31][32]. Virulence factors are expressed and secreted by the pathogen, allowing it to colonize the host, establish infection, and evade the immune system, and can be classified into different groups, depending on their function [33]. Cytosolic factors allow bacteria to adapt to the host environment by undergoing quick adaptative metabolic, physiological, and morphological shifts. Membrane-associated factors facilitate bacteria adhesion and invasion of host cells, and secretory factors allow them to evade the host’s innate and adaptive immune system as well as cause tissue damage [33]. Due to this, moonlight proteins are good targets to treat bacteria-caused diseases because they can be involved in many steps of infection. Major groups of bacterial moonlight proteins implicated in virulence include metabolic enzymes of the glycolytic and other metabolic pathways, molecular chaperones, and protein-folding catalysts [34]. Among these, most moonlighting virulence factors mediate adhesion and modulation of leukocyte activity.

Proteins with moonlight activity often exert their canonical function in a different cell compartment of their moonlight function. One example is the glycolytic enzyme Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), the first identified bacterial moonlight protein [35]. GAPDH catalyzes the conversion of D-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate to 3-phosphoD-glyceroyl phosphate in glycolysis when present inside the cell, and on the cell surface of group A streptococci can present adhesive functions in vitro [36]. Besides presenting more than one function in group A streptococci, GAPDH moonlighting activity is also present in other species. In Bacillus anthracis, Lactobacillus crispatus, Staphylococcus aureus, and Staphylococcus pneumoniae GAPDH also binds to plasmin. Furthermore, GAPDH can bind fibronectin, an extracellular matrix component (ECM), and bind complement protein C5a, mediating immune evasion, among other described functions [35].

Bacterial adherence factors are cell surface proteins that form and maintain physical interactions with host cells and tissues. This feature is crucial in pathogenic bacteria because it promotes infection but is also important in commensal bacteria to maintain a symbiotic relationship with the host [32]. Enolase is a well-characterized moonlight protein that converts 2-phosphoglycerate to phosphoenolpyruvate in glycolysis and can exert other functions on the surface of pathogens [32]. Enolase can bind to the host’s ECM or airway mucins and can bind to the coagulation cascade protease plasminogen in Borrelia burgdorferi, Candida albicans, Streptococcus pneumoniae, among others, contributing to bacterial virulence [37].

Moonlight cytosolic proteins can be secreted as signaling molecules, regulating various cell types in an organism or modulating host responses in the case of a pathogen. In the cytosol, chaperones are proteins that bind and assist the folding or unfolding of macromolecular structures in order to prevent misfolding and promote reassembly and correct assembly of protein complexes [32]. In mammals, heat shock protein 60 (Hsp60), GroEL, is a chaperone that mediates mitochondrial protein import in the cell [32]. However, it has been demonstrated that bacterial Hsp60/GroEL can mediate adhesion in several species, including Clostridium difficile, Helicobacter pylori, and Chlamydia pneumoniae, contributing to their virulence [32]. Elongation factor (EF)-tu is another example. It is a cytoplasmic protein important in protein synthesis that transports and catalyzes the binding of aminoacyl-tRNA to the ribosome. However, besides its canonical function, EF-tu can act also as an adhesin at the surface of several pathogens such as Mycobacterium pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa by binding fibronectin and plasminogen, respectively [38][39].

Among these multitasking proteins are also proteolytic enzymes mainly located in the membrane or secreted and recognized as virulence factors in various pathogenic bacteria [40]. These molecules cleave specific peptide bonds of target proteins, resulting in activation, inactivation, generation of new proteins, and even changing protein function, being important in colonization and evasion of the host immune defenses, acquisition of nutrients for growth and proliferation, and facilitation of dissemination or tissue damage during infection [41][42]. For example, streptococcal C5a peptidase is a surface serine protease that cleaves and inactivates complement protein C5a. Furthermore, this protease can mediate fibronectin binding, acting as an adhesin. This moonlight function is important for streptococci virulence, helping in the attachment and invasion of eukaryotic cells [43]. Additionally, Escherichia coli presents the protease OmpT, which acts as an adhesin to human cells [44][45].

3. Moonlighting in Rickettsiales

The order Rickettsiales comprises a diverse group of Gram-negative alphaproteobacteria with an obligatory intracellular lifestyle and a mandatory transmission cycle that includes arthropods as hosts, reservoirs, and vectors [46]. The order is divided into two families (Anaplasmataceae and Rickettsiaceae), seven major genera (Anaplasma, Ehrlichia, Wolbachia, Neorickettsia, Rickettsia, Orientia, and SAR11), and comprises at least 87 species that exhibit high diversity in cell structure, vector preference, host cell type preference, pathogenicity and infection cycle [1].

Organisms of the order Rickettsiales have been found in all continents and are associated with diverse habitats in which arthropod species such as fleas, lice, ticks, and mites are present [47][48][49]. Rickettsiales organisms can be transmitted to various mammalian hosts, including humans and animals (e.g., rodents, cattle), through the saliva or feces of feeding arthropods [48]. Rickettsial pathogens are inoculated into the blood or skin during the blood meal and are disseminated through the body via the blood and/or lymphatic system [48]. Once inside the mammalian host, the tropism to mammalian cells can vary between species infecting erythrocytes (Anaplasma marginale), endothelial cells (Rickettsia spp., Orientia tsutsugamushi), dendritic cells (Orientia tsutsugamushi), neutrophils (Anaplasma phagocytophilum), or macrophages (Orientia tsutsugamushi, Ehrlichia chaffeensis, and some Rickettsia spp.) [1].

The order Rickettsiales includes species that can be non-pathogenic, animal pathogens, and human pathogens [1]. The clinical spectrum of rickettsial disease in humans varies widely, ranging from mild illness to rapidly fatal disease [50][51]. The extensive range of human diseases caused by Rickettsiales organisms includes human granulocytic anaplasmosis (Anaplasma phogocytophilum), human monocytic ehrlichiosis (Ehrlichia caffeensis), human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (Ehrlichia ewingii), scrub typhus (Orientia tsutsugamushi), epidemic typhus/Brill-Zinsser disease (Rickettsia prowazekii), rickettsialpox (Rickettsia akari), Mediterranean spotted fever (Rickettsia conorii), and Rocky Mountain spotted fever (Rickettsia rickettsii), among many others [1][50].

Historically, rickettsial agents such as R. prowazekii have been important causes of human morbidity and mortality, being associated with several million deaths in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) [52]. Despite significant advances in science/modern medicine, diseases caused by Rickettsiales species remain a major public health concern. For example, scrub typhus threatens one billion people and causes nearly a million cases per year in the Asia-Pacific area [51][53]. A systematic review on the burden of scrub typhus in India revealed that scrub typhus accounts for at least 25.3% among individuals with acute undifferentiated febrile illness [54].

Economic globalization, changes in land use and urbanization, increase in travel, and global warming have all been postulated to raise the distribution and incidence of diseases caused by Rickettsiales [55][56]. Indeed, these diseases are gaining global momentum because of their resurgence patterns, being reported not only in previously endemic regions but also new regions [57][58]. As already mentioned, climate and environmental changes have already contributed to expanding the range of several tick species into higher latitudes in North America, thus resulting in the emergence of anaplasmosis and other tick-borne diseases [59][60]. Global warming has also been associated with the increased occurrence of scrub typhus, with 1 °C rise in temperature causing an increase of 15% in monthly cases [61].

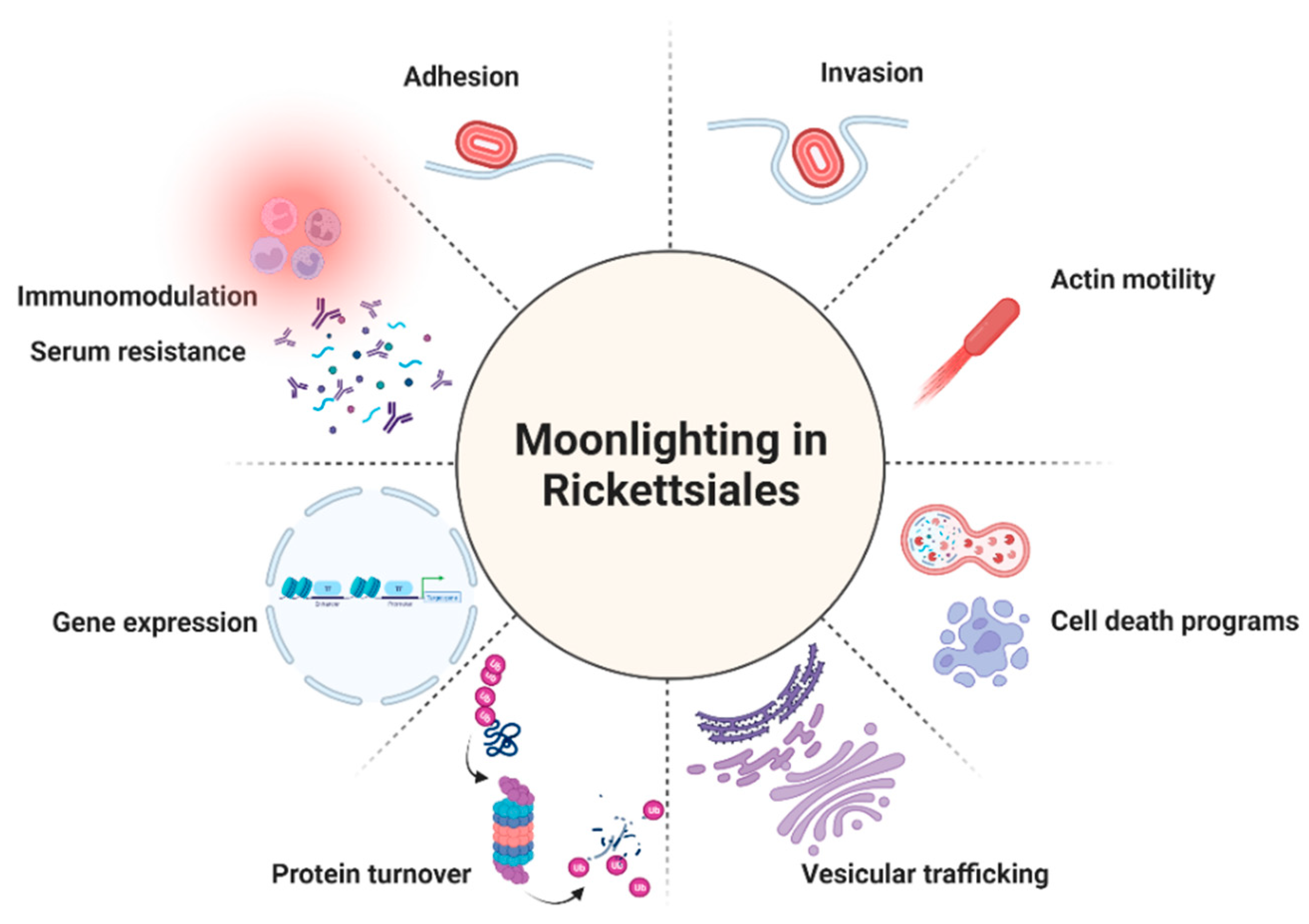

As summarized in the previous sections, moonlighting/multitasking proteins contribute significantly to the population of virulence factors employed by bacteria to aid colonization and induce disease. Strikingly, by searching MoonProt 3.0 or MultitaskProtDB-II, researchers could only find one protein from Rickettsiales organisms annotated in the second database, the parvulin-like PPIase from R. prowazekii. However, “multitaskers” represent a growing class of proteins among these obligate bacteria, highlighting the relevance of this phenomenon to expand their capacity to interfere with multiple host cell processes (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The multiple roles of the reported moonlighting/multitasking proteins in Rickettsiales. Created with BioRender.com.

Figure 1. The multiple roles of the reported moonlighting/multitasking proteins in Rickettsiales. Created with BioRender.com.References

- Salje, J. Cells within cells: Rickettsiales and the obligate intracellular bacterial lifestyle. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2021, 19, 375–390.

- Khatat, S.E.H.; Daminet, S.; Duchateau, L.; Elhachimi, L.; Kachani, M.; Sahibi, H. Epidemiological and Clinicopathological Features of Anaplasma phagocytophilum Infection in Dogs: A Systematic Review. Front. Veter.-Sci. 2021, 8, 686644.

- Matei, I.A.; Estrada-Peña, A.; Cutler, S.J.; Vayssier-Taussat, M.; Castro, L.V.; Potkonjak, A.; Zeller, H.; Mihalca, A.D. A review on the eco-epidemiology and clinical management of human granulocytic anaplasmosis and its agent in Europe. Parasites Vectors 2019, 12, 599.

- Zhang, L.; Cui, F.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Yang, S. Investigation of anaplasmosis in Yiyuan County, Shandong Province, China. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2011, 4, 568–572.

- Gettings, J.R.; Self, S.C.W.; McMahan, C.S.; Brown, D.A.; Nordone, S.K.; Yabsley, M.J. Local and regional temporal trends (2013–2019) of canine Ehrlichia spp. seroprevalence in the USA. Parasites Vectors 2020, 13, 153.

- Luce-Fedrow, A.; Lehman, M.L.; Kelly, D.J.; Mullins, K.; Maina, A.N.; Stewart, R.L.; Ge, H.; John, H.S.; Jiang, J.; Richards, A.L. A Review of Scrub Typhus (Orientia tsutsugamushi and Related Organisms): Then, Now, and Tomorrow. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2018, 3, 8.

- Chakraborty, S.; Sarma, N. Scrub Typhus: An Emerging Threat. Indian J. Dermatol. 2017, 62, 478–485.

- Parola, P.; Paddock, C.D.; Socolovschi, C.; Labruna, M.B.; Mediannikov, O.; Kernif, T.; Abdad, M.Y.; Stenos, J.; Bitam, I.; Fournier, P.-E.; et al. Update on Tick-Borne Rickettsioses around the World: A Geographic Approach. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 26, 657–702.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Epidemiological Situation of Rickettsioses in EU/EFTA Countries; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2013.

- Binder, A.M.; Armstrong, P.A. Increase in Reports of Tick-Borne Rickettsial Diseases in the United States. Am. J. Nurs. 2019, 119, 20–21.

- Drexler, N.A.; Dahlgren, F.; Massung, R.F.; Behravesh, C.B.; Heitman, K.N.; Paddock, C.D. National Surveillance of Spotted Fever Group Rickettsioses in the United States, 2008–2012. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2016, 94, 26–34.

- Álvarez-Hernández, G.; Roldán, J.F.G.; Milan, N.S.H.; Lash, R.R.; Behravesh, C.B.; Paddock, C.D. Rocky Mountain spotted fever in Mexico: Past, present, and future. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, e189–e196.

- Spernovasilis, N.; Markaki, I.; Papadakis, M.; Mazonakis, N.; Ierodiakonou, D. Mediterranean Spotted Fever: Current Knowledge and Recent Advances. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 172.

- Buczek, W.; Koman-Iżko, A.; Buczek, A.M.; Bartosik, K.; Kulina, D.; Ciura, D. Spotted fever group rickettsiae transmitted by Dermacentor ticks and determinants of their spread in Europe. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2020, 27, 505–511.

- Heinrich, N.; Dill, T.; Dobler, G.; Clowes, P.; Kroidl, I.; Starke, M.; Ntinginya, N.E.; Maboko, L.; Löscher, T.; Hoelscher, M.; et al. High Seroprevalence for Spotted Fever Group Rickettsiae, Is Associated with Higher Temperatures and Rural Environment in Mbeya Region, Southwestern Tanzania. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0003626.

- Martinez, M.A.C.; Ramírez-Hernández, A.; Blanton, L.S. Manifestations and Management of Flea-Borne Rickettsioses. Res. Rep. Trop. Med. 2021, 12, 1–14.

- Brown, L.D.; Macaluso, K.R. Rickettsia felis, an Emerging Flea-Borne Rickettsiosis. Curr. Trop. Med. Rep. 2016, 3, 27–39.

- Maina, A.N.; Jiang, J.; Luce-Fedrow, A.; John, H.K.S.; Farris, C.M.; Richards, A.L. Worldwide Presence and Features of Flea-Borne Rickettsia asembonensis. Front. Veter.-Sci. 2019, 5, 334.

- Piotrowski, M.; Rymaszewska, A. Expansion of Tick-Borne Rickettsioses in the World. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1906.

- Jeffery, C.J. Moonlighting proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1999, 24, 8–11.

- Chen, C.; Liu, H.; Zabad, S.; Rivera, N.; Rowin, E.; Hassan, M.; De Jesus, S.M.G.; Santos, P.S.L.; Kravchenko, K.; Mikhova, M.; et al. MoonProt 3.0: An update of the moonlighting proteins database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 49, D368–D372.

- Franco-Serrano, L.; Hernández, S.; Calvo, A.; Severi, M.A.; Ferragut, G.; Pérez-Pons, J.; Piñol, J.; Pich, Ò.; Mozo-Villarias, Á.; Amela, I.; et al. MultitaskProtDB-II: An update of a database of multitasking/moonlighting proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D645–D648.

- Huberts, D.H.; van der Klei, I.J. Moonlighting proteins: An intriguing mode of multitasking. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1803, 520–525.

- Jeffery, C.J. Why study moonlighting proteins? Front. Genet. 2015, 6, 211.

- Hernandez, S.; Franco, L.; Calvo, A.; Ferragut, G.; Hermoso, A.; Amela, I.; Gomez, A.; Querol, E.; Cedano, J. Bioinformatics and Moonlighting Proteins. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2015, 3, 90.

- Khan, I.K.; Bhuiyan, M.; Kihara, D. DextMP: Deep dive into text for predicting moonlighting proteins. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, i83–i91.

- Shirafkan, F.; Gharaghani, S.; Rahimian, K.; Sajedi, R.H.; Zahiri, J. Moonlighting protein prediction using physico-chemical and evolutional properties via machine learning methods. BMC Bioinform. 2021, 22, 261.

- Ribeiro, D.M.; Briere, G.; Bely, B.; Spinelli, L.; Brun, C. MoonDB 2.0: An updated database of extreme multifunctional and moonlighting proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 47, D398–D402.

- Jeffery, C.J. Protein moonlighting: What is it, and why is it important? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 373, 20160523.

- Wang, G.; Xia, Y.; Cui, J.; Gu, Z.; Song, Y.; Chen, Y.Q.; Chen, H.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W. The Roles of Moonlighting Proteins in Bacteria. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2014, 16, 15–22.

- Espinosa-Cantú, A.; Cruz-Bonilla, E.; Noda-Garcia, L.; DeLuna, A. Multiple Forms of Multifunctional Proteins in Health and Disease. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 451.

- Jeffery, C. Intracellular proteins moonlighting as bacterial adhesion factors. AIMS Microbiol. 2018, 4, 362–376.

- Sharma, A.K.; Dhasmana, N.; Dubey, N.; Kumar, N.; Gangwal, A.; Gupta, M.; Singh, Y. Bacterial Virulence Factors: Secreted for Survival. Indian J. Microbiol. 2017, 57, 1–10.

- Henderson, B.; Martin, A. Bacterial Virulence in the Moonlight: Multitasking Bacterial Moonlighting Proteins Are Virulence Determinants in Infectious Disease. Infect. Immun. 2011, 79, 3476–3491.

- Kainulainen, V.; Korhonen, T.K. Dancing to Another Tune—Adhesive Moonlighting Proteins in Bacteria. Biology 2014, 3, 178–204.

- Pancholi, V.; Fischetti, V.A. A major surface protein on group A streptococci is a glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase with multiple binding activity. J. Exp. Med. 1992, 176, 415–426.

- Amblee, V.; Jeffery, C.J. Physical Features of Intracellular Proteins that Moonlight on the Cell Surface. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130575.

- Dallo, S.F.; Kannan, T.R.; Blaylock, M.W.; Baseman, J.B. Elongation factor Tu and E1 β subunit of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex act as fibronectin binding proteins in Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 2002, 46, 1041–1051.

- Kunert, A.; Losse, J.; Gruszin, C.; Hühn, M.; Kaendler, K.; Mikkat, S.; Volke, D.; Hoffmann, R.; Jokiranta, T.S.; Seeberger, H.; et al. Immune Evasion of the Human Pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Elongation Factor Tuf is a Factor H and Plasminogen Binding Protein. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 2979–2988.

- Culp, E.; Wright, G.D. Bacterial proteases, untapped antimicrobial drug targets. J. Antibiot. 2017, 70, 366–377.

- Lebrun, I.; Marques-Porto, R.; Pereira, A.; Perpetuo, E. Bacterial Toxins: An Overview on Bacterial Proteases and their Action as Virulence Factors. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2009, 9, 820–828.

- Rogers, L.D.; Overall, C.M. Proteolytic Post-translational Modification of Proteins: Proteomic Tools and Methodology. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2013, 12, 3532–3542.

- Beckmann, C.; Waggoner, J.D.; Harris, T.O.; Tamura, G.S.; Rubens, C.E. Identification of Novel Adhesins from Group B Streptococci by Use of Phage Display Reveals that C5a Peptidase Mediates Fibronectin Binding. Infect. Immun. 2002, 70, 2869–2876.

- Torres, A.; Chamorro-Veloso, N.; Costa, P.; Cádiz, L.; Del Canto, F.; Venegas, S.; Nitsche, M.L.; Coloma-Rivero, R.; Montero, D.; Vidal, R. Deciphering Additional Roles for the EF-Tu, l-Asparaginase II and OmpT Proteins of Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1184.

- Wan, L.; Guo, Y.; Hui, C.-Y.; Liu, X.-L.; Zhang, W.-B.; Cao, H. The surface protease ompT serves as Escherichia coli K1 adhesin in binding to human brain micro vascular endothelial cells. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 27, 617–624.

- Dumler, J.S.; Walker, D.H. Order II. Rickettsiales. In Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, 2nd ed.; Garrity, G.M., Brenner, D.J., Krieg, N.R., Staley, J.T., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005; Volume 2.

- Vescovo, I.A.L.; Golemba, M.D.; Di Lello, F.A.; Culasso, A.C.; Levin, G.; Ruberto, L.; Mac Cormack, W.P.; López, J.L. Rich bacterial assemblages from Maritime Antarctica (Potter Cove, South Shetlands) reveal several kinds of endemic and undescribed phylotypes. Rev. Argent. Microbiol. 2014, 46, 218–230.

- McQuiston, J.H.; Paddock, C.D. Public Health: Rickettsial Infections and Epidemiology. In Intracellular Pathogens II; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 40–83.

- Wood, H.; Artsob, H. Spotted Fever Group Rickettsiae: A Brief Review and a Canadian Perspective. Zoonoses Public Health 2012, 59, 65–79.

- Dumler, J.S. Clinical Disease: Current Treatment and New Challenges. In Intracellular Pathogens II; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 1–39.

- Sahni, A.; Fang, R.; Sahni, S.K.; Walker, D.H. Pathogenesis of Rickettsial Diseases: Pathogenic and Immune Mechanisms of an Endotheliotropic Infection. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2019, 14, 127–152.

- Kelly, D.J.; Richards, A.L.; Temenak, J.; Strickman, D.; Dasch, G.A. The Past and Present Threat of Rickettsial Diseases to Military Medicine and International Public Health. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002, 34, S145–S169.

- Xu, G.; Walker, D.H.; Jupiter, D.; Melby, P.C.; Arcari, C.M. A review of the global epidemiology of scrub typhus. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0006062.

- Devasagayam, E.; Dayanand, D.; Kundu, D.; Kamath, M.S.; Kirubakaran, R.; Varghese, G.M. The burden of scrub typhus in India: A systematic review. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021, 15, e0009619.

- El-Sayed, A.; Kamel, M. Climatic changes and their role in emergence and re-emergence of diseases. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 22336–22352.

- Wu, T.; Perrings, C.; Kinzig, A.; Collins, J.P.; Minteer, B.A.; Daszak, P. Economic growth, urbanization, globalization, and the risks of emerging infectious diseases in China: A review. Ambio 2017, 46, 18–29.

- Blazejak, K.; Janecek, E.; Strube, C. A 10-year surveillance of Rickettsiales (Rickettsia spp. and Anaplasma phagocytophilum) in the city of Hanover, Germany, reveals Rickettsia spp. as emerging pathogens in ticks. Parasites Vectors 2017, 10, 588.

- John, R.; Varghese, G.M. Scrub typhus: A reemerging infection. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 33, 365–371.

- Alkishe, A.; Raghavan, R.K.; Peterson, A.T. Likely Geographic Distributional Shifts among Medically Important Tick Species and Tick-Associated Diseases under Climate Change in North America: A Review. Insects 2021, 12, 225.

- Nelder, M.P.; Russell, C.B.; Lindsay, L.R.; Dibernardo, A.; Brandon, N.C.; Pritchard, J.; Johnson, S.; Cronin, K.; Patel, S.N. Recent Emergence of Anaplasma phagocytophilum in Ontario, Canada: Early Serological and Entomological Indicators. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2019, 101, 1249–1258.

- Li, T.; Yang, Z.; Dong, Z.; Wang, M. Meteorological factors and risk of scrub typhus in Guangzhou, southern China, 2006–2012. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 139.

More

Information

Subjects:

Microbiology

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

786

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

21 Mar 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No