Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gennady Kolesnikov | + 2285 word(s) | 2285 | 2022-03-11 05:05:59 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 2285 | 2022-03-21 03:04:10 | | | | |

| 3 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 2285 | 2022-03-21 03:04:37 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Kolesnikov, G. Arginine Accumulation in Scots Pine Needles. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20746 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Kolesnikov G. Arginine Accumulation in Scots Pine Needles. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20746. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Kolesnikov, Gennady. "Arginine Accumulation in Scots Pine Needles" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20746 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Kolesnikov, G. (2022, March 18). Arginine Accumulation in Scots Pine Needles. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20746

Kolesnikov, Gennady. "Arginine Accumulation in Scots Pine Needles." Encyclopedia. Web. 18 March, 2022.

Copy Citation

Free arginine (Arg) content was observed to multiply when the level of nitrogen (N) nutrition was high, and additional fertilization with boron (B) potentiated this effect. Owing to this feature, conifers can be suggested for use as bioproducers of Arg. Concentrations of Arg in relation to N and B fertilization needed to be better understood.

Pinus sylvestris L.

needles

nitrogen

boron

fertilization doses

1. Introduction

Boreal coniferous forests usually grow on acidic podzolic forest soils that are deficient in mineral nutrients, first of all in nitrogen (N). Boron (B) is deficient for the growth of conifers under the conditions of Fennoscandia [1][2][3][4][5][6][7]. Excessive competition between trees for nutrients, light, and water is prevented by precommercial cuts (thinning) with retention of a sufficient number of trees to secure high productivity of the site [8], while the supply of nutrients to trees is optimized by fertilization [9][10][11]. Alongside many other factors, the effect of fertilization on tree species depends on the content of nutrients in soil and on fertilizer form and dosage [6][8][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25].

Precommercial thinning results in an increased output of lumber, but the question of improving financial performance remains open [26]. Increasing the profitability of silvicultural actions (thinning, pruning, and fertilization) in young and middle-aged stands can be augmented by processing and utilizing the removed green tissue, thereby reducing the costs. Data on the accumulation of aboveground biomass in coniferous species are necessary to assess the reserves of tree greenery suitable for harvesting plant materials enriched with biologically active substances (BAS) [27][28][29][30].

The growing demand for BAS and exhaustion of the traditional sources of plant material necessitates the search for new resources. A topical task is finding new sources of BAS of high practical value. Yet, large-scale exploitation of natural sources of BAS and their massive harvesting is fraught with environmental problems. The use of foliage contributes to solving environmental problems [30].

Tree foliage contains various organic compounds used in the manufacturing of nutritional and pharmaceutical products. Ethnobotanical and ethnomedicine literature is used to search for new sources of raw materials in feed production and pharmaceuticals [29]. The water-soluble fraction of coniferous greenery contains free amino acids, in particular L-arginine (arginine). A hypothesis has been proposed about the nutrient and synergistic role of arginine and its metabolites, which supplement the role of vitamin C [29]. It is an ingredient of many drugs and antiviral agents. Being a source of nitrogen oxide—a potent vasodilator and neuromediator—it is applied in medicine [31][32]. The demand for Arg is high in carnivores, fish, and poultry [33][34]. Arg boosts the growth of animals, their productivity, and their immune response [35][36].

The development of technologies for modifying the biochemical composition of coniferous woody greens to obtain plant raw materials enriched with BAS necessary for practical purposes is promising for the purposeful use of new raw materials.

Different plant species have very different needs for Arg. In the organs of one plant species, Arg can accumulate in a wide range of values, depending on the phenophase and growing conditions [37][38][39].

Arg content in needles was seen to multiply where N nutrition was elevated as a result of economic activities or in experiments with mineral nutrition of conifers [5][39][40][41][42][43][44]. Fertilization of B significantly increased the effect. The finding can be used to produce Arg-enriched coniferous tree foliage [30]. A novel protocol for supplying coniferous plants with N and B has been designed to cause plant material to be used as feedstock for manufacturing Arg-rich coniferous products—conifer meal and aqueous conifer extract [35][36]. Positive results were obtained in the trials of Arg-rich coniferous extract in fur animal farming, specifically in American mink (Mustela vison Shr.) [36]. The extract improved their immune status and survival rates. Administered as a feed supplement, conifer meal made of Arg-enriched needles promoted animals growth and productivity [35].

Arg-rich woody green tissue can be obtained during thinning in young stands, when relieving linear facilities from woody vegetation, or from forest crops planted specifically for woody green tissue cultivation [30]. The potential of the resource was estimated by studying the distribution of Arg in crowns of 10-year-old Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) trees in an experiment with modulation of N and B supply [30]. The intake, distribution, and consumption of N in conifers is known to depend on the timing of fertilizer placement in soil, and the composition of N compounds in conifers’ organs and tissues varies among phenological phases over the annual cycle [5][39]. The seasonal dynamics of Arg content in conifers in relation to the timing of N and B application to soil was studied [45].

2. Study Area

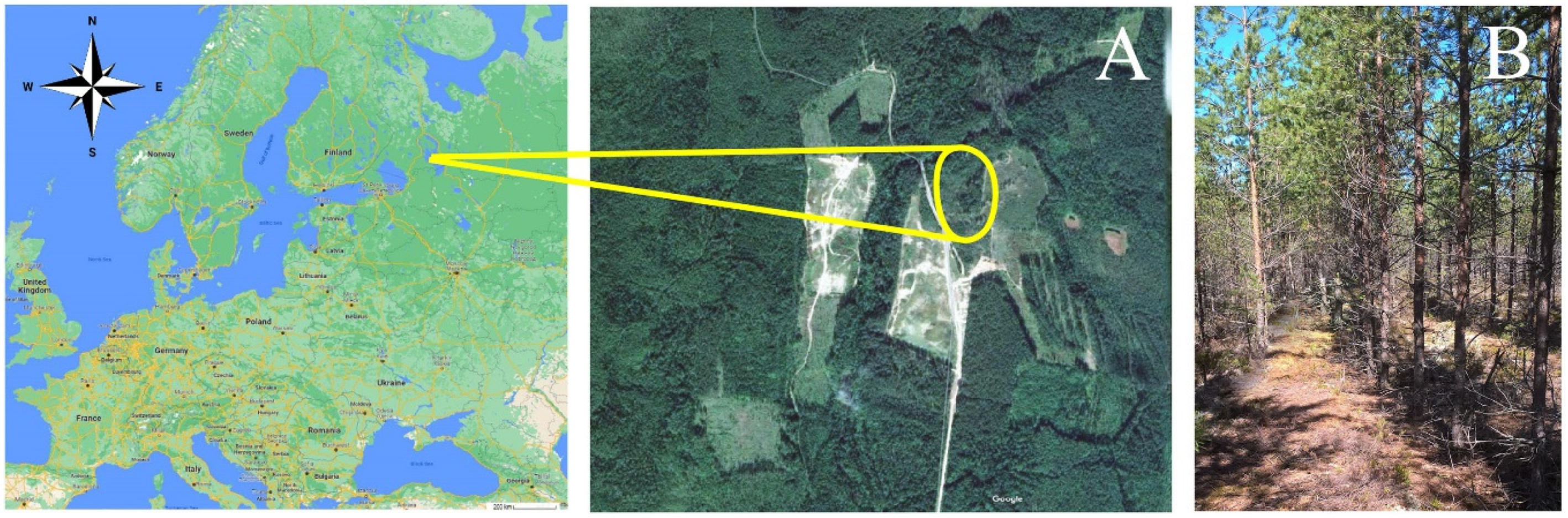

The area is situated in the northwest of European Russia (61°56′ N, 34°21′ E), in the middle taiga subzone. The region belongs to the zone of cold and wet. The average annual air temperature is +3.1 °C, and the average annual amount of atmospheric precipitation is 611 mm. The duration of the frost-free period is up to 120–130 days, and the active growing season is around 100 days or more. Studies were carried out in 16-year-old Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) crops planted in a sand quarry in 1998 using containerized seedlings (Figure 1). The research site is almost flat with a slope of up to 1° orientated towards the southwest.

Figure 1. Geographic location of the study sites in the Karelia Republic, Russian Federation (A); 16-year-old Scots pine crops (B).

3. Nitrogen Content in Needles

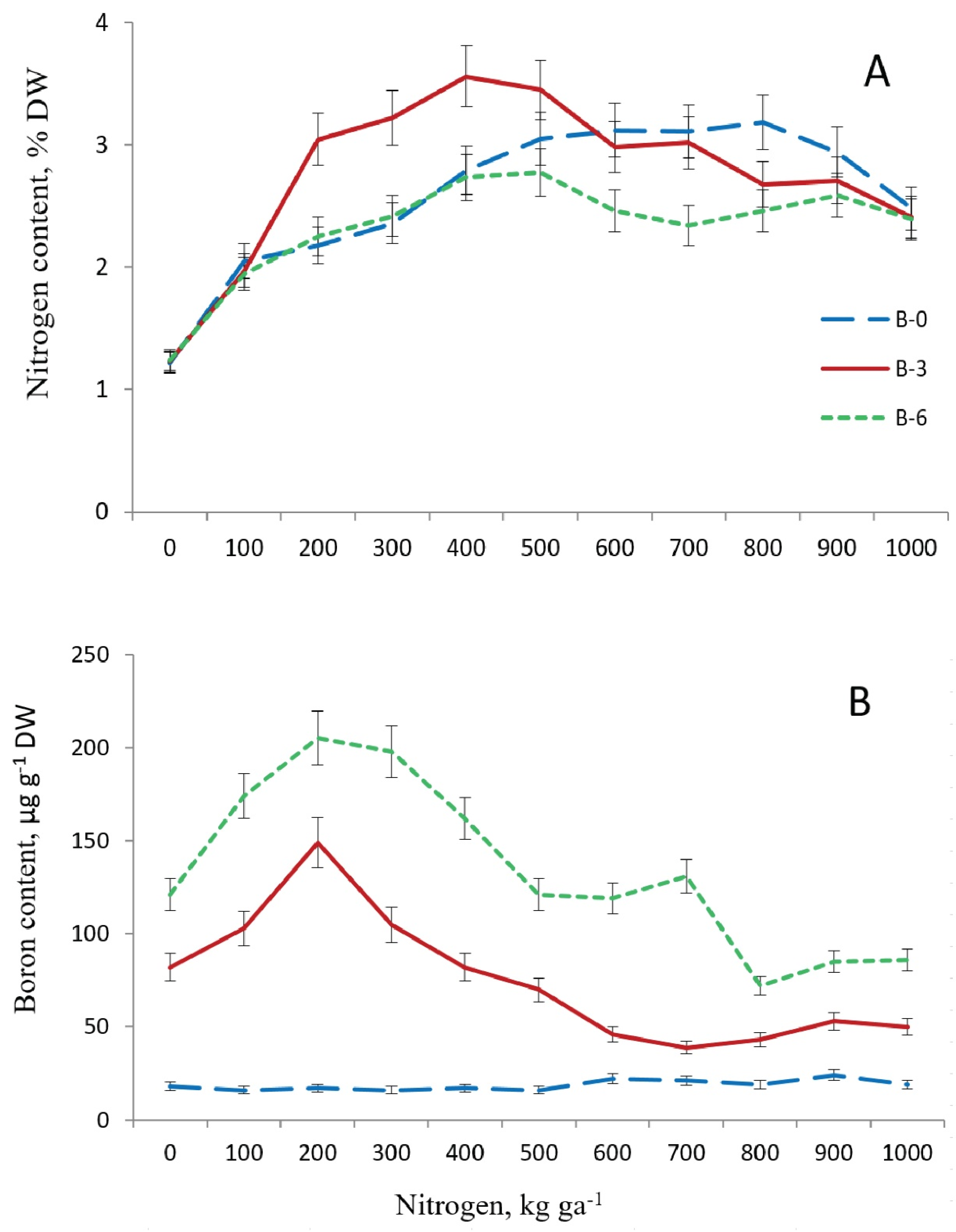

N content in one-year-old needles was 1.2% in the control plot in the last third of September 2014 (Figure 2). It rose to 2.1% after application of N fertilizers to the soil at dose 100 kg ha−1 in all variants of B supply.

Figure 2. Nitrogen (A) and boron (B) content in one-year-old needles of 16-year old Pinus sylvestris L. depending on the doses of their application to soil. B0, B3, B6—boron doses of 0, 3.0, 6.0 kg ha−1, respectively. September 2014 (observations per plot n = 3).

N levels in needles in the treatments with nitrogen at 200–400 kg ha−1 were the same as in the variants with boron deficit and its surplus, rising to 2.8%.

As N dosage was increased in B-deficient plots, N levels in needles rose (to 3.2%) until the N dose was 800 kg ha−1, and then, as N doses were elevated further, the level declined to 2.5%. In the B-excessive variant, N content in needles changed little between fertilization at 400 kg ha−1 and the highest dose. In the variant with optimal B supply (3 kg ha−1), N content in needles increased more significantly with elevation of fertilization doses to 400 kg ha−1 (to 3.6%) than in the plots with B deficit and surplus, but starting at 600 kg N ha−1 and higher, it declined to the same level as in the other two variants of B supply. Thus, the optimal dose of B, as opposed to its deficit and surplus, augmented N levels to the maximum in needles where N fertilization doses were 200–500 kg ha−1. Its levels became equal (up to 2.5%) in the needles of trees of three variants of B supply at the nitrogen dose 1000 kg ha−1.

4. Boron Content in Needles

B content in one-year-old needles of pine trees from the control plot in September 2014 was low and amounted to 17 µg g−1. In B-deficient settings, the element’s level in needles changed insignificantly when different N doses were applied. In B-fertilized plots, foliar B content in pine trees was higher than in B-deficient plots in all N dosage variants. In the variants with optimal and excessive B supply, its foliar content was more significantly augmented by application of the second dose of N compared to the first dose, i.e., from 103 and 174 µg g−1 to 149 and 205 µg g−1, respectively. As N doses were further raised, foliar B levels declined, starting with 300 kg N ha−1 in B-optimal plots and starting with 400 kg N ha−1 in B-excessive plots, yet remaining higher in the variants with B boron surplus compared to boron optimum. The decline in foliar B content continued until the nitrogen dose of 600 kg ha−1 in B-optimal plots and until 800 kg N ha−1 in B-excessive plots. When even higher N doses were applied, B content in needles changed little in the two B supply variants. In treatments with the highest N dose, B content in needles was 50 and 86 µg mg−1 in B-optimal and B-excessive plots, respectively. Thus, application of the second N dose coupled with optimal and excessive B supply promoted foliar B content more significantly than the first N dose. Elevation of N doses to higher levels, from 300 to 600 kg ha−1 (for B optimum) or from 400 to 800 kg ha−1 (for B surplus), entailed a decline in the B content in needles.

5. Arginine Content in Needles

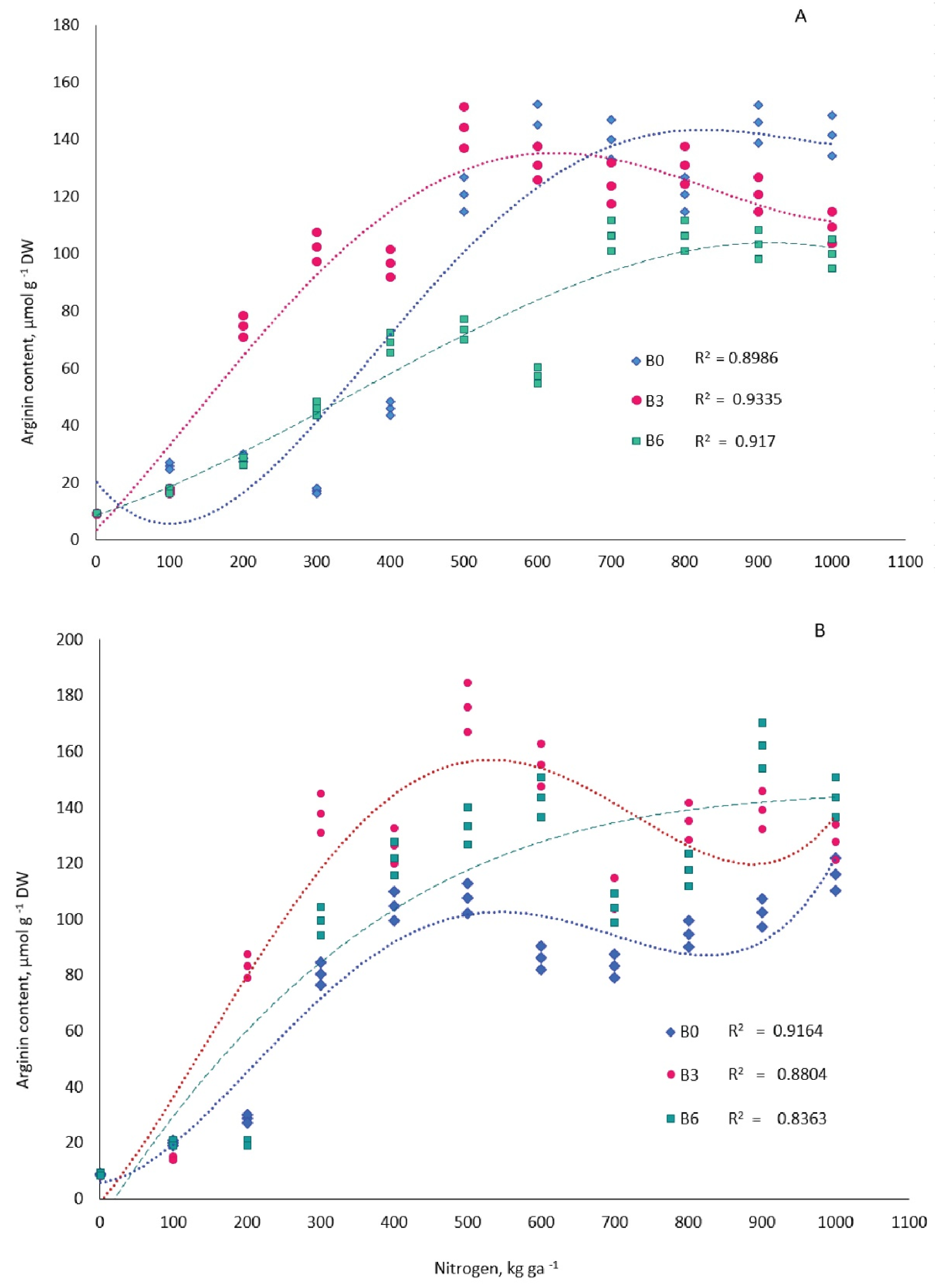

The treatments of N fertilizers alone and combined with B significantly increased the content of Arg in one-year-old needles of pine trees (Figure 3, Table 1). Differences in tree needle Arg concentration between the 11 treatments of N levels at the three treatments of B levels (B0, B3, and B6), analyzed with a two-sample t-test with equal variances, was significant (p = 0.05) in September in all variants except N0 (Table 2). In March, no significant differences were observed in variants N0, N4, and N10. Followed for pairwise comparison, when the analysis of variance showed significance (p = 0.05), it was possible to reveal that the accumulation of Arg in needles significantly differed in three B levels in variants N3–N5 in September and N3 and N5 in March. Regression analysis results between Arg concentration and treatments of N levels are shown in Figure 3 and Table 1. In the last third of September 2014, foliar Arg levels in plots with soil B deficiency (B0) were similar to the control in the treatments with the first three N doses (N1–N3) and then increased to 145.0 µmol g−1 in the treatments with N at 600 kg ha−1, and they showed little change at higher N doses.

Figure 3. Dependence of the accumulation of arginine in the one-year-old needles of 16-year old Pinus sylvestris L. on the nitrogen fertilizers on three backgrounds of boron supply. B0, B3, B6—boron doses of 0, 3.0, 6.0 kg ha−1, respectively. (A) September 2014; (B) March 2015 (for regressive equation, see Table 1).

Table 1. Regression analyses were performed using arginine concentration (μmol g−1 DW) in the one-year-old needles of 16-year-old Pinus sylvestris L. as dependent variables (y) and N fertilizers (kg ga−1) as independent variables (x). Polynomial relationships and the coefficients of determination (R2) were determined for each variant of boron treatment.

| Treatment | Regressive Equation | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| September 2014 | ||

| B0 | y = 9 ×10−10x4 − 2 × 10−6x3 + 0.0019x2 − 0.3177x + 20.476 | 0.8986 |

| B3 | y = 6 × 10−10x4 − 1 × 10−6x3 + 0.0004x2 + 0.2673x + 3.4668 | 0.8986 |

| B6 | y = −1 × 10−7x3 + 0.00026x2 + 8.5814 | 0.8986 |

| March 2015 | ||

| B0 | y = 2 × 10−9x4 − 3 × 10−6x3 + 0.0013x2 + 0.034x + 5.780 | 0.9164 |

| B3 | y = 2 × 10−9x4 − 3 × 10−6x3 + 0.001x2 + 0.3066x − 1.3232 | 0.8804 |

| B6 | y = 1 × 10−7x3 + 0.0004x2 + 0.4149x + 8.1520 | 0.8363 |

Table 2. Two-sample t-test analysis with equal variances (α = 0.05) was applied to estimate significance of post hoc differences between treatments of different B-fertilized doses at the same levels of N on arginine content (μmol g−1) in one-year-old needles of 16-year old Pinus sylvestris L. in September 2014 and March 2015. Doses of N were from 0 to 1000 kg ha−1 with a 100 kg ha−1 step (N0, N1, … N10) and B doses were 0 (B0), 3.0 (B3), and 6.0 (B6) kg ha−1. Different lower case letters (a, b, or c) beside means indicate significant post hoc differences between treatments (Tukey’s test). (p = 0.05).

| Needle Arg Concentration, μmol g−1 DW | t-Statistic | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N, kg ga−1 | B0 | B3 | B6 | p-Value B0–B3 |

p-Value B0–B6 |

p-Value B3–B6 |

|||

| M | ±SE | M | ±SE | M | ±SE | ||||

| September 2014 | |||||||||

| 0 | 9.2 a | 0.64 | 9.1 a | 0.64 | 9.3 a | 0.65 | 0.802 | ||

| 100 | 25.9 a | 1.81 | 17.2 b | 1.20 | 17.2 b | 1.20 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.947 |

| 200 | 28.7 a | 2.01 | 74.7 b | 5.23 | 27.6 a | 1.93 | <<0.05 | 0.393 | <<0.05 |

| 300 | 17.2 a | 1.20 | 102.3 b | 7.16 | 46 c | 3.22 | <<0.05 | <<0.05 | <<0.05 |

| 400 | 46 a | 3.22 | 96.6 b | 6.76 | 69 c | 4.83 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| 500 | 120.7 a | 8.45 | 144.3 b | 10.10 | 73.6 c | 5.15 | 0.044 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| 600 | 145 a | 10.15 | 131 a | 9.17 | 57.5 b | 4.03 | 0.202 | 0.000 | 0.001 |

| 700 | 140 a | 9.80 | 123.6 ac | 8.65 | 106.3 c | 7.44 | 0.137 | 0.003 | 0.021 |

| 800 | 120.7 a | 8.45 | 131 a | 9.17 | 106.3 b | 7.44 | 0.264 | 0.036 | 0.007 |

| 900 | 146 a | 10.22 | 120.7 a | 8.45 | 103.4 b | 7.24 | 0.050 | 0.001 | 0.020 |

| 1000 | 141.4 a | 9.90 | 109.2 b | 7.64 | 100 b | 7.00 | 0.021 | 0.001 | 0.098 |

| March 2015 | |||||||||

| 0 | 8.6 a | 0.60 | 8.5 a | 0.60 | 8.7 a | 0.61 | 0.893 | ||

| 100 | 20.1 a | 1.41 | 14.4 b | 1.01 | 20.2 a | 1.41 | 0.016 | 0.954 | 0.015 |

| 200 | 28.7 a | 2.01 | 83.3 b | 5.83 | 20.1 c | 1.41 | 0.000 | 0.013 | 0.000 |

| 300 | 80.5 a | 5.64 | 137.9 b | 9.65 | 99.4 c | 6.96 | 0.003 | 0.023 | 0.017 |

| 400 | 104.6 a | 7.32 | 126.4 a | 8.85 | 121.8 a | 8.53 | 0.083 | ||

| 500 | 107.5 a | 7.53 | 175.9 b | 12.31 | 133.3 c | 9.33 | 0.005 | 0.049 | 0.029 |

| 600 | 86.2 a | 6.03 | 155.2 b | 10.86 | 143.7 b | 10.06 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.400 |

| 700 | 83.3 a | 5.83 | 109.2 bc | 7.64 | 104 ac | 7.28 | 0.031 | 0.055 | 0.583 |

| 800 | 94.8 a | 6.64 | 135.1 bc | 9.46 | 117.8 ac | 8.25 | 0.013 | 0.058 | 0.170 |

| 900 | 102.3 a | 7.16 | 139.1 b | 9.74 | 162.1 b | 11.35 | 0.021 | 0.006 | 0.136 |

| 1000 | 116.1 a | 8.13 | 127.6 a | 8.93 | 143.7 a | 10.06 | 0.313 | ||

N—nitrogen dose; M—average value needle arginine concentration (μmol g−1); ±SE—standard error based on within-plot error (n = 3), a, b, c beside means indicate significant post hoc differences be-tween treatments.

The amount of Arg in the needles of trees in the control variant (B0N0) during the study period did not exceed 8.6 µmol g−1. Optimal B availability to pine, unlike its shortage and surplus, helped significantly augment foliar Arg content (to 102.3 µmol g−1) when coupled with the placement of the second and third N doses (N2 and N3). In the variants with B deficit or surplus coupled with the same N doses, on the other hand, the level of amino acid in needles was lower—17.2 and 46.0 µmol g−1, respectively. In treatments with N doses above 500 kg ha−1, differences in amino acid content between the B deficit and B optimum variants became less significant (Table 2), while the Arg level in the variant with B surplus was lower than in the other two variants.

In the last third of March 2015, as well as in September 2014, Arginine content in one-year-old pine needles in B-deficient plots was similar to that of the control when the first two N doses were applied; as N doses were raised to 500 kg ha−1, the amino acid content rose to 107.5 µmol g−1, and when the N dose was increased further, the change in Arg was insignificant. In plots with optimal B supply in March as well as in September, the first N dose had no significant effect on Arg content in needles; the second and further N doses, up to 500 kg ha−1 inclusively, significantly promoted the Arg level to 175.9 µmol g−1. Foliar Arg level in March, as compared to September, was promoted even more significantly by the application of N starting with the second dose in the B-optimal variant and with the third dose where B was in surplus. The level of the amino acid in needles in the variant with B deficiency, on the contrary, was lower in March compared to September in treatments with N in doses above 500 kg ha−1 and was also lower in the N treatments of 300 kg ha−1 and higher compared to trees from B-fertilized plots.

References

- Wikner, B. Distribution and mobility of boron in forest ecosystems. Commun. Inst. For. Fenn. 1983, 116, 131–141.

- Stone, E.L. Boron deficiency and excess in forest trees: A review. For. Ecol. Manag. 1990, 37, 49–75.

- Hopmans, P.; Clerehan, S. Growth and uptake of N, P, K and B by Pinus radiata D. Don in response to applications of borax. Plant Soil 1991, 131, 115–127.

- Tamm, C.O. Nitrogen in Terrestrial Ecosystems: Questions of Productivity, Vegetational Changes, and Ecosystem Stability. Ecological STUDIES 81; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1991; Volume 81, p. 115.

- Chernobrovkina, N.P. Ecophysiological Characteristics of Nitrogen Utilization by Scots Pine; Nauka: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2001; p. 175. (In Russian)

- Brockley, R.P. Effects of nitrogen and boron fertilization on foliar boron nutrition and growth in two different lodgepole pine ecosystems. Can. J. For. Res. 2003, 33, 988–996.

- Magill, A.H.; Aber, J.D.; Currie, W.S.; Nadelhoffer, K.J.; Martin, M.E.; McDowell, W.H.; Melillo, J.M.; Steudler, P. Ecosystem response to 15 years of chronic nitrogen additions at the Harvard Forest LTER, Massachusetts, USA. For. Ecol. Manag. 2004, 196, 7–28.

- De Vries, W.C. Effects on trees: Stem growth. In The Condition of Forests in Europe. United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution, International Co-Operative Programme on Assessment and Monitoring of Air Pollution Effects on Forests (ICP Forests); Thünen Institute: Eberswalde, Germany, 2013; pp. 30–31.

- Ulvcrona, T.; Ulvcrona, K.A. The effects of pre-commercial thinning and fertilization on characteristics of juvenile clearwood of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.). Forestry 2011, 84, 207–219.

- Pukkala, T. Optimal nitrogen fertilization of boreal conifer forest. For. Ecosyst. 2017, 4, 3.

- Del Rio, M.; Bravo-Oviedo, A.; Pretzsch, H.; Lof, M.; Ruiz-Peinado, R. A review of thinning effects on Scots pine stands: From growth and yield to new challenges under global change. For. Syst. 2017, 26, eR03S.

- Mead, D.J.; Gadgil, R.L. Fertilizer use in established radiata pine stands in New Zealand. N. Z. J. For. Sci. 1978, 8, 70–104.

- Hopmans, P.; Flinn, D.W. Boron deficiency in Pinus radiate D. Don and the effect of applied boron on height growth and nutrient uptake. Plant Soil 1984, 79, 295–298.

- Sikstrom, U. Effects of low-dose liming and nitrogen fertilization on stemwood growth and needle properties of Picea abies and Pinus sylvestris. For. Ecol. Manag. 1997, 95, 261–274.

- Lehto, T.; Kallio, E.; Aphalo, P.J. Boron mobility in two coniferous species. Ann. Bot. 2000, 86, 547–550.

- Jacobson, S.; Pettersson, F. An assessment of different fertilization regimes in three boreal coniferous stands. Silva Fenn. 2010, 44, 815–827.

- Berg, J.; Nilsson, U.; Allen, H.L.; Johansson, U.; Fahlvik, N. Long-term responses of Scots pine and Norway spruce stands in Sweden to repeated fertilization and thinning. For. Ecol. Manag. 2014, 320, 118–128.

- From, F.; Strengbom, J.; Nordin, A. Residual long-term effects of forest fertilization on tree growth and nitrogen turnover in boreal forest. Forests 2015, 6, 1145–1156.

- Binkley, D.; Hogberg, P. Revisiting the influence of nitrogen deposition on Swedish forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 368, 222–239.

- Carlsson, J.; Egertsdotter, U.; Ganeteg, U.; Svennerstam, H. Nitrogen utilization during germination of somatic embryos of Norway spruce: Revealing the importance of supplied glutamin for nitrogen metabolism. Trees 2019, 33, 383–394.

- Rocha, J.S.; Calzavara, A.K.; Bianchini, E.; Pimenta, J.A.; Stolf-Moreira, R.; Oliveira, H.C. Nitrogen supplementation improves the high-light acclimation of Guazuma ulmifolia Lam. seedlings. Trees 2019, 33, 421–431.

- Valinger, E.; Sjögren, H.; Nord, G.; Cedergren, J. Effects on stem growth of Scots pine 33 years after thinning and/or fertilization in northern Sweden. Scand. J. For. Res. 2019, 34, 33–38.

- Guo, J.; Gao, Y.; Eissenstat, D.M.; He, C.; Sheng, L. Belowground responses of woody plants to nitrogen addition in a phosphorus-rich region of northeast China. Trees 2020, 34, 143–154.

- Gilliam, F.S. Response of Temperate Forest Ecosystems under Decreased Nitrogen Deposition: Research Challenges and Opportunities. Forests 2021, 12, 509.

- Gruffman, L.; Jämtgård, S.; Näsholm, T. Plant nitrogen status and co-occurrence of organic and inorganic nitrogen sources influence root uptake by Scots pine seedlings. Tree Physiol. 2014, 34, 205–213.

- Tanger, S.M.; Blazier, M.A.; Holley, A.G.; McConnell, T.E.; Vanderschaaf, C.; Clason, T.R.; Dipesh, K.C. Financial performance of diverse levels of early competition suppression and pre-commercial thinning on loblolly pine stand development. New For. 2021, 52, 217–235.

- Zianis, D.; Muukkonen, P.; Makipaa, R.; Mencuccini, M. Biomass and stem volume equations for tree species in Europe. Silva Fenn. Monogr. 2005, 4, 63.

- Lehtonen, A. Estimating foliage biomass in Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) and Norway spruce (Picea abies) plots. Tree Physiol. 2005, 25, 803–811.

- Durzan, D.J. Arginine, scurvy, and Jacques Cartier’s “tree of life”. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2009, 5, 5.

- Robonen, E.V.; Chernobrovkina, N.P.; Zaitseva, M.I.; Raevsky, B.V.; Egorova, A.V.; Kolesnikov, G.N. Obtaining woody greens enriched with L-Arg during forestry management of young scots pine stands (scientific review). Bulletin of Higher Educational Institutions. Lesn. Zhurnal 2020, 5, 9–37. (In Russian)

- Brunini, T.M.; Mendes-Ribeiro, A.C.; Ellory, J.C.; Mann, G.E. Platelet nitric oxide synthesis in uremia and malnutrition: A role for L_Arg supplementation in vascular protection? Cardiovasc. Res. 2007, 73, 359–367.

- Stief, T.W. Inhibition of thrombin in plasma by heparin or Arg. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 2007, 13, 146–153.

- Ball, R.O.; Urschel, K.L.; Pencharz, P.B. Nutritional consequences of interspecies differences in Arg and lysine metabolism. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 1626–1641.

- Eisert, R.L. Hypercarnivory and the brain: Protein requirements of cats reconsidered. J. Comp. Physiol. B 2011, 181, 1–17.

- Korotkiy, V.P.; Chernobrovkina, N.P.; Marisov, S.S.; Velikanov, V.I.; Robonen, E.V. Biochemical production based on raw materials from forest. In International Scientific Conference Innovation and Technologies in Forestry. Materials of the International Scientific-Practical Conference; Series “Proceedings of the St. Petersburg Research Institute of Forestry”; Saint Petersburg Forestry Research Institute: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2011; pp. 92–95.

- Unzhakov, A.R.; Tyutyunnik, N.N.; Uzenbaeva, L.B.; Baishnikova, I.V.; Antonova, E.P.; Chernobrovkina, N.P.; Robonen, E.V.; Ilyukha, V.A. Physiological State of American Mink (Mustela vison) Puppies under the Action of an Extract from Needles Enriched with L-Arginine; Karelian Research Centre of RAS: Petrozavodsk, Russia, 2014; Volume 5, pp. 222–227.

- Apostol, L.; Sorin, C.; Mosoiu, C.; Mustatea, G.; Cucu, S. Nutrient composition of partially defatted milk thistle seeds. Sci. Bull. Ser. F Biotechnol. 2017, XXI, 165–172.

- Ramazanov, A.S.; Balayeva, S.A. Amino acid composition of fruitssilybum marianum, growing in the territory of the republic of Dagestan. Chem. Plant Raw Mater. 2020, 3, 215–223.

- Näsholm, T.; Ericsson, A. Seasonal changes in amino acids, protein and total nitrogen in needles of fertilized Scots pine trees. Tree Physiol. 1990, 6, 267–281.

- Pietila, M.; Lahdesmaki, P.; Pietilainen, P.; Ferm, A.; Hytonen, J.; Patila, A. High Nitrogen Deposition Causes Changes in Amino Acid Concentrations and Protein Spectra in Needles of the Scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris). Environ. Pollut. 1991, 72, 103–115.

- Gezelius, K.; Nasholm, T. Free amino acids and protein in Scots pine seedlings cultivated at different nutrient availabilities. Tree Physiol. 1993, 13, 71–86.

- Huhn, B.G.; Schulz, H. Contents of free amino acids in Scots pine needles from field sites with different levels of nitrogen deposition. New Phytol. 1996, 134, 95–101.

- Durzan, D.J. Arg and the shade tolerance of white spruce saplings entering winter dormancy. J. For. Sci. 2010, 56, 77–83.

- Tarvainen, L.; Lutz, M.; Rantfors, M.; Nasholm, T.; Wallin, G. Increased Needle Nitrogen Contents Did Not Improve Shoot Photosynthetic Performance of Mature Nitrogen-Poor Scots Pine Trees. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1051.

- Chernobrovkina, N.P.; Robonen, E.V.; Repin, A.V.; Makarova, T.N. Seasonal dynamics of Arg content in Pinus sylvestris L. needles depending on the timing of nitrogen and boron application. Khimiya Rastit. Syr’ya 2018, 2, 159–168. (In Russian)

More

Information

Subjects:

Agriculture, Dairy & Animal Science

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

588

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

21 Mar 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No