Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wenceslao Santiago García | + 2752 word(s) | 2752 | 2022-03-02 07:12:28 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | -47 word(s) | 2705 | 2022-03-15 02:49:54 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Santiago García, W. Forest Management Plans in Southern Mexico. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20570 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Santiago García W. Forest Management Plans in Southern Mexico. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20570. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Santiago García, Wenceslao. "Forest Management Plans in Southern Mexico" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20570 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Santiago García, W. (2022, March 14). Forest Management Plans in Southern Mexico. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20570

Santiago García, Wenceslao. "Forest Management Plans in Southern Mexico." Encyclopedia. Web. 14 March, 2022.

Copy Citation

Mexican forest communities are a worldwide model of community forest management for timber production and conservation of forest resources under the form of community forest enterprises (CFEs).

conservation

community forestry

forest management

forests

productivity

1. Introduction

In Mexico, the area covered by temperate forests and rainforest is estimated at around 64.3 million of hectares, from which there is an average annual production of 6.8 million m3 of roundwood [1]. Of this volume, CFEs contribute around 85% [2][3].

Approximately 60% of Mexico’s forests belong to local communities [4], which practice autonomy in their management and use [5]. However, in the middle of the last century, a strategy was applied for forest administration based on state control through concessions to parastatal enterprises [6]. In the 1986 forestry law, the forest concession system was annulled [7], and communities’ right to use their forest resources was recognized. In addition, the agreement to develop integral forest management plans (FMPs) was established.

In general, community forestry involves the active participation of people from local communities in forestry activities. This emerged in the late 1970s, when the state’s control over resources and its ability to protect and manage forests sustainably were questioned as a consequence of concerns about increased deforestation [8]. In Mexico, with the modifications of the 1986 forest law, the communities were given the task of looking for new tools for the use and management of forests, while mitigating environmental impacts and guaranteeing the supply of forest raw material, thus giving way to community forestry [7]. In addition, several silvicultural regimes began to be used to modify the structure and increase productivity of forests communities, mainly using methods such as seed-tree, liberation cutting, precommercial thinning, and commercial thinning.

Some years after the 1986 forest law, modifications to forestry regulations led to passage of the 1992, 2003, and 2018 laws. These laws established the objectives of conservation, protection, restoration, production, management practices, and use, all of which were aimed at achieving optimal and sustainable productivity of forest resources [9]. Likewise, it is recognized that, in forest management, economic, social, and ecological factors must be considered [10]. Therefore, the objectives of forest management in a communal forest also involve social welfare, job creation, and the development of alternative economic activities [2][11].

In the Sierra Juárez, Oaxaca, southern Mexico, in the beginning of the 1980s with the end of the concession to the parastatal enterprise “Fábricas de Papel Tuxtepec” (FAPATUX), which had a 25 year concession in the area, several communities were organized for the utilization and extraction of their forest resources [12][13][14]. In 1981, the forestry organization “Lic. José López Portillo” was constituted by the communities Ixtlán de Juárez, Capulálpam de Méndez, La Trinidad Ixtlán, and Santiago Xiacui, with the support of FAPATUX, disintegrating in 1988, leaving only Ixtlán de Juárez [15][16]. From 1988 to 1991, the CFE of Ixtlán was restructured, and the “Unidad Comunal Forestal Agropecuaria y de Servicios” (UCFAS) was integrated. By 1991, UCFAS began efforts to have their own technical forestry groups (with community members) and FMPs [15][17].

The community of Ixtlán de Juárez, like other forest communities in Oaxaca, is a representative case of community forest management in Mexico, where logging is the main economic activity [3][18]. Therefore, to maintain the productive and conservation values of forest resources, there is a need to evaluate over time the effects of the implementation of silvicultural practices and management regimes. For this reason, some studies have evaluated the structure, richness, and composition of tree species at coarse scales of analysis [19][20][21][22], while others have focused on ecosystem functioning by assessing productivity in terms of biomass, carbon, basal area, number of trees, volume, and increment at the stand or sub-stand level [23][24][25][26][27].

The Ixtlán de Juárez community began with its first timber FMP in 1993. This forest management plan used a cutting cycle from 1993 to 2002, aiming to achieve good silvicultural management, as well as forest conservation and creation of sources of employment for the community. In 2004, the second FMP was applied. It was suspended for 2 years due to a pest infestation in several sub-stands of the community forest, but resumed in 2006. The third FMP (2015–2024) is currently under development. Throughout the previous FMPs, various systems and silvicultural regimes have been applied according to the forest’s conditions and its response to regeneration, growth, and adaptation to the treatments applied.

2. Background of the Study Area

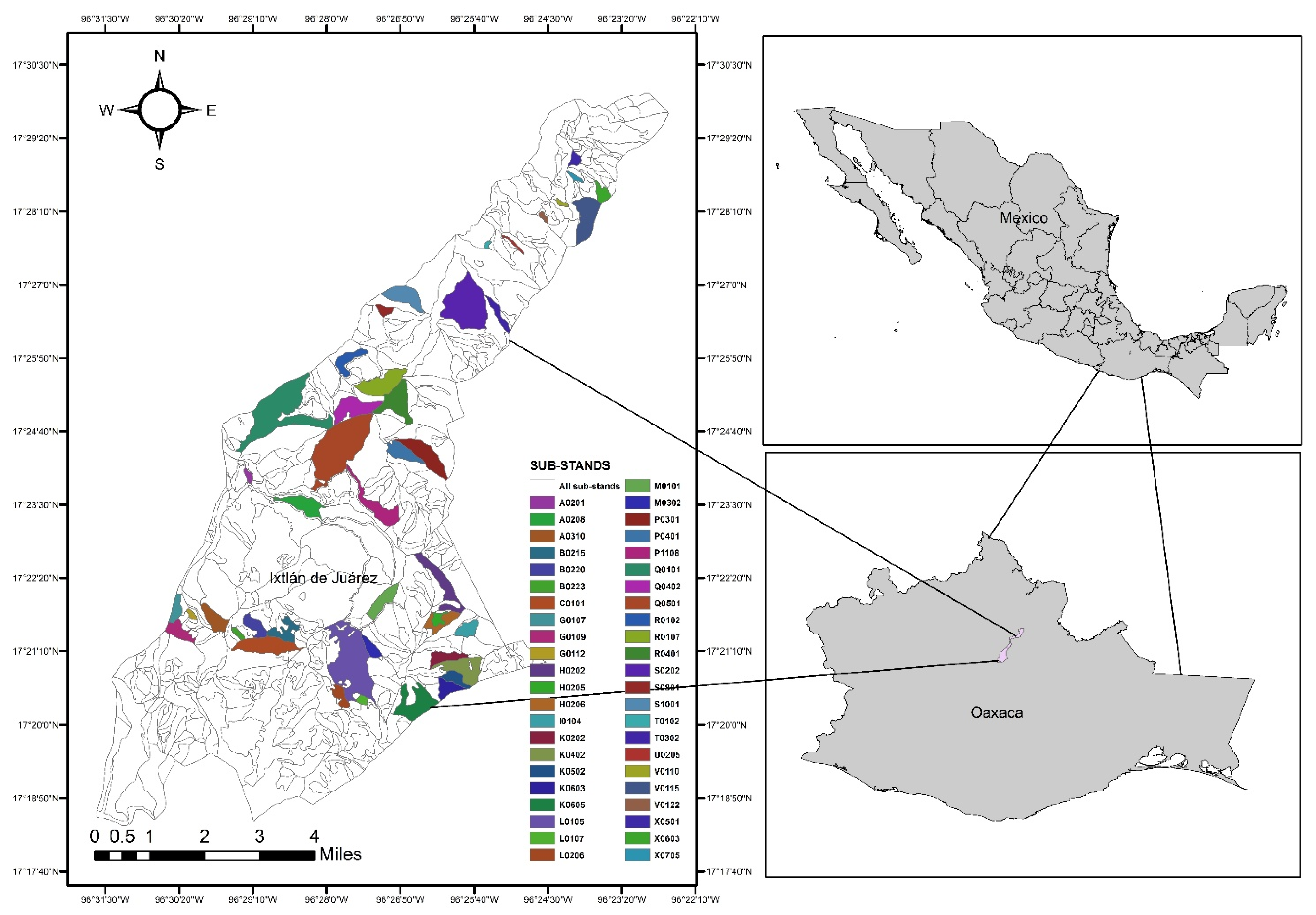

The entry was conducted in the communal forest under management of the community of Ixtlán de Juárez, Oaxaca, Mexico (Figure 1), located within the geographic coordinates 17°18′16″–17°30′00″ N and 96°21′29″–96°31′38″ W, ranging in altitude from 2200 m to 3100 m. Most of the pine–oak forest land area has a humid temperate climate with summer rains, and the pine and oak species are mainly harvested species groups [16][28].

Figure 1. Location of the study area.

In the analytical comparison of the Ixtlán de Juárez community FMPs, data from three forest inventories of forest management planning were used. These datasets support the cutting cycles 1993–2002 (FMP1), 2004–2013 (FMP2), and 2015–2024 (FMP3). The most important applied silvicultural treatments for FMPs were seed-tree and single-tree selection for FMP1, while, for FMP2 and FMP3, strip clearcutting and single-tree selection were applied.

In the inventory for FMP1, around 2000 0.10 ha sampling plots were measured under a stratified random sampling design. For FMP2, the same sampling design was used, and 1696 sampling plots were evaluated, while, for FMP3, a stratified systematic sampling design was implemented where researchers measured 1081 sampling plots, of which 41 0.010 ha plots were used to facilitate evaluation of the regeneration response in areas of alternate strip clearcutting.

3. Comparison of Sub-Stand Variables of the Three Forest Management Plans

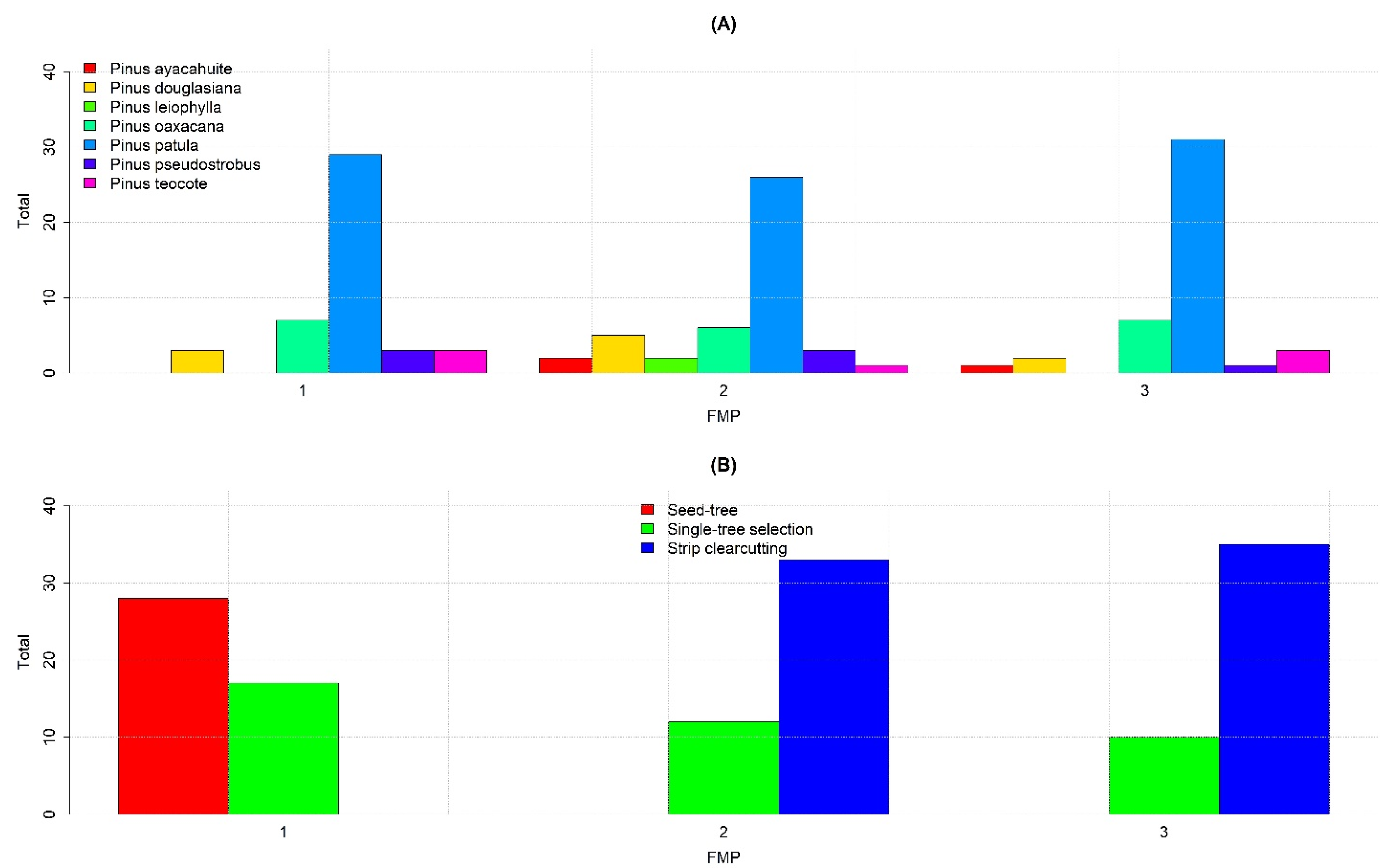

The comparison of the selected 45 sub-stands in the three FMPs showed that Pinus patula Schiede ex Schltdl. & Cham. is the most dominant species (Figure 2A). In the case of the third forest inventory, in 31 sub-stands, Pinus patula was the dominant species, followed by Pinus oaxacana Mirov in seven sub-stands. The reported stocks for Pinus patula and for Pinus oaxacana are 462,904.12 m3 total tree volume and 144,458.48 m3 total tree volume, respectively [29]. According to TIASA [15], 45% of pine stocks are Pinus patula, followed by Pinus oaxacana, Pinus teocote Schied. ex Schltdl. & Cham., Pinus douglasiana Martínez, and Pinus ayacahuite Ehrenb. ex Schltdl.; in another study, Castellanos-Bolaños et al. [30] determined that Pinus patula is distributed over approximately 5000 ha and is one of the most economically important species due to its rapid growth and wood quality.

Figure 2. Dominant pine species (A) and silvicultural treatments (B) applied in the sub-stands evaluated by FMP.

According to the first FMP [15], with the data obtained from the first forest inventory and its analysis, it was possible to determine that several of the sub-stands were overmature, and young sub-stands were scarce, while there was an abundance of oaks and other broadleaf trees. This aspect is attributed to the fact that, during the time of concessions and management by the FAPATUX enterprise, logging was clearly selective toward individuals with larger diameters, and necessary stand treatments were not given, promoting the growth of other species different from pine species [16]. Ramírez-Santiago [31] pointed out that regeneration of pines is low when the single-tree selection method is used due to their shade intolerance, while it favors establishment of oaks and other broadleaf trees.

In the case of FMP1 in many of the sub-stands, seed-tree treatments were applied (Figure 2B) with intensive thinning due to the dominance of broadleaf trees species. However, Ramírez-Santiago [31] reported that there were no significant differences in regeneration with the single-tree selection method. This is because, although the seed-tree method suggests intensive extraction and opening of gaps, in the case of the Ixtlán de Juárez community, the process was not followed in the proper way. Because oaks did not have a stable market, they were not used, causing similar results in both silvicultural methods. The low utilization of oak was also attributed to the low cost per cubic meter, which did not exceed extraction costs [16][29].

Currently in the community, management of oaks is mostly aimed at the production of charcoal in brick kilns, with an approximate production of 140 t per month. In addition, the energy characteristics of wood and charcoal of other broadleaf tree species have been evaluated [32], but the market conditions that allow the adequate use of these species are not yet available.

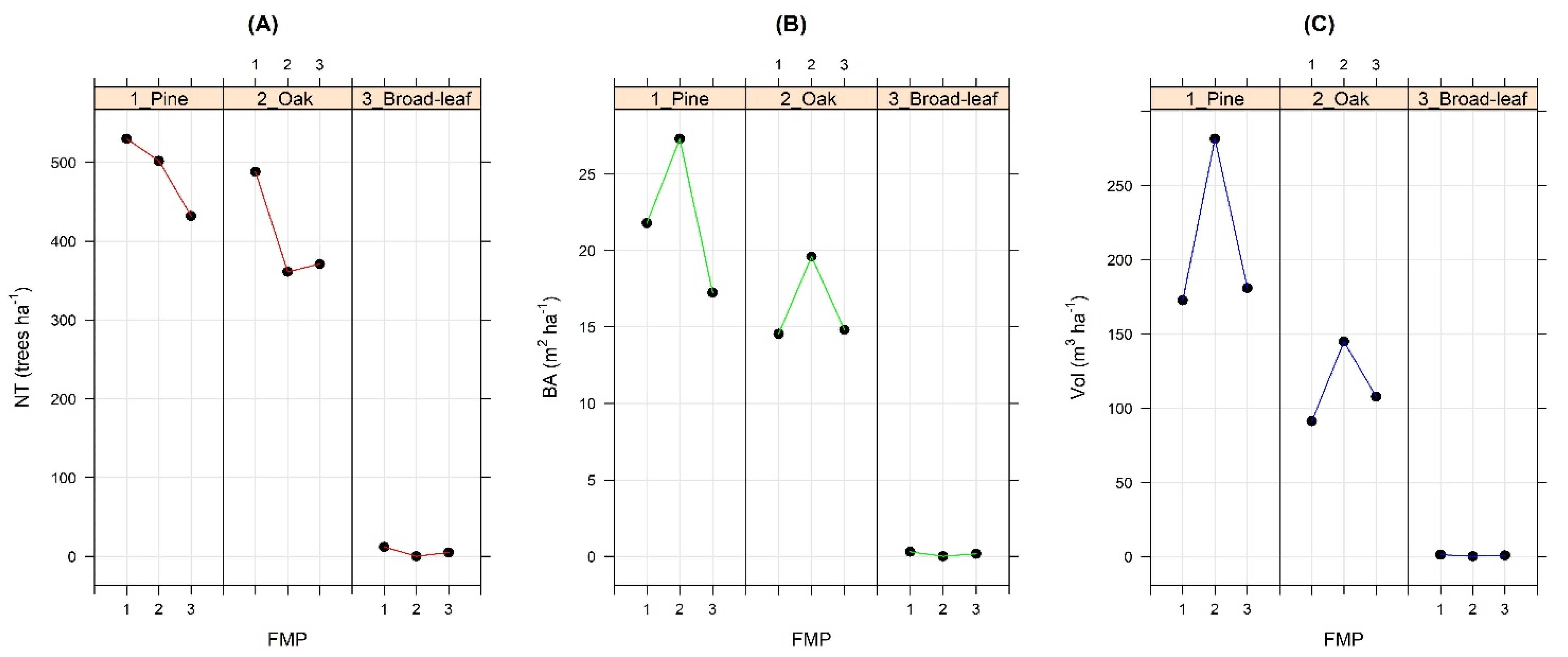

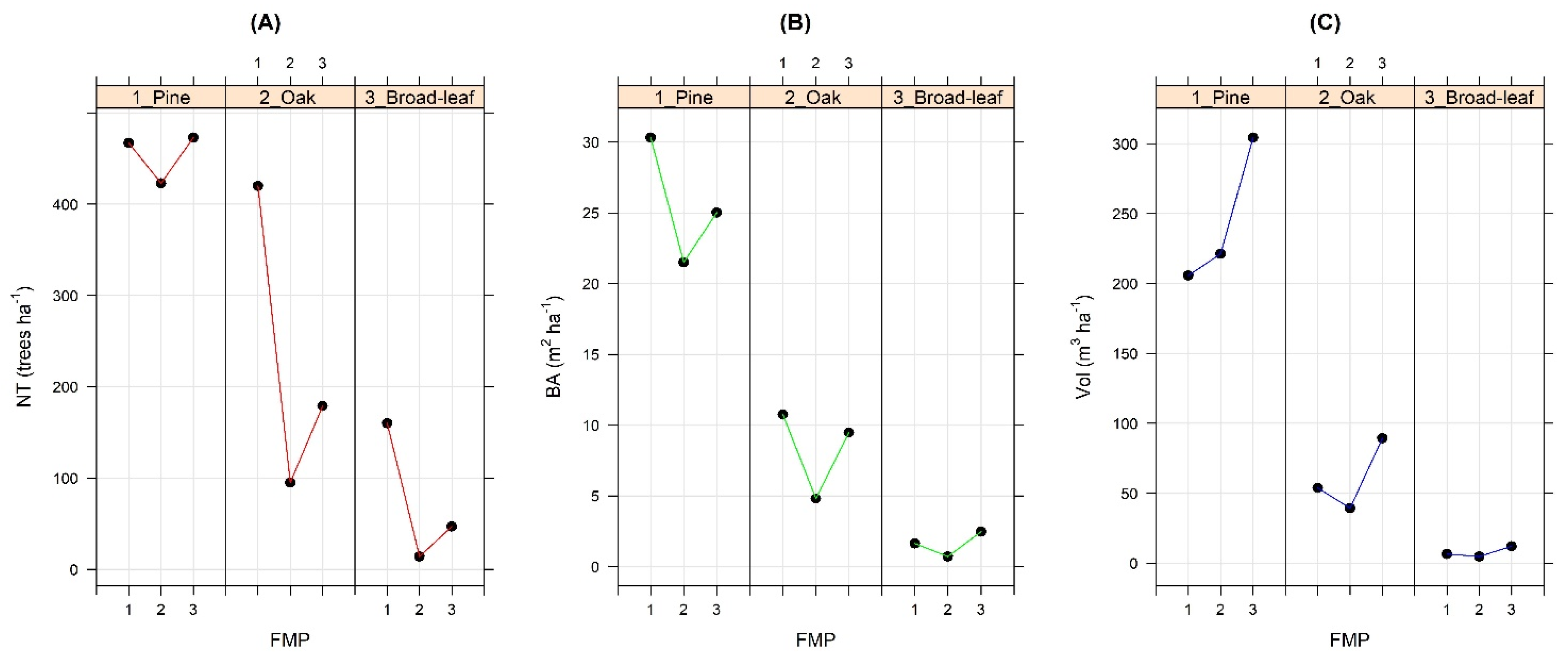

In the comparative analysis of the FMPs, the A0208 sub-stand (area of 30.78 ha) in the first plan partially received the seed-tree treatment, whereas, in the last two plans, it received strip clearcutting. The NT decreased from FMP2 to FMP3 (Figure 3A). However, BA and Vol increased in the genera Pinus and Quercus from FMP1 to FMP2 (Figure 3B,C), and, in the case of other broadleaf trees, it remained constant or did not differ noticeably.

Figure 3. Comparison of the number of trees (NT) (A), basal area (BA) (B), and volume (Vol) (C) under the three forest management plans (FMPs) in the A0208 sub-stand.

Intensive management such as the application of alternate strip clearcutting and thinning shows that, although NT decreases, Vol and BA tend to increase in the following cutting cycles due to greater spacing between individuals that reduces competition, to the litterfall that allows nutrients to be reincorporated into the forest floor, and to the capacity of the young stands to absorb these nutrients [33]. Forest growth is related to the level of forest site productivity and stand density. Dieler et al. [26] pointed out that productivity in biomass and volume is a central indicator of ecosystem functioning at the stand level, and that this productivity improves significantly with moderate thinning. On the other hand, the average diameter at breast height (dbh) of the stand is strongly determined by density, and interventions such as thinning produce an instantaneous change in the value of this variable [34][35]. In addition, with the opening of gaps, seedlings tend to establish and grow rapidly. It is important to note that most pine species in the study area are shade-intolerant (except Pinus ayacahuite); thus, the implementation of these practices favors their growth and natural regeneration.

From the inventory for FMP3 (2015–2024), the 0.010 ha regeneration evaluation plots with strip clearcutting treatment generated an average regeneration density of 2392 trees·ha−1 with an interval of 500–6500 trees·ha−1, coinciding with the study carried out by Santiago [36], who reported densities of 2400 trees·ha−1 in sub-stands with the strip clearcutting treatment. On the other hand, Rodríguez-Ortiz et al. [37] classified the strip clearcutting areas as high regeneration (>1500 trees·ha−1) in the same study area. According to Moreno [38], the recommended natural regeneration is from 1283 to 2890 trees·ha−1; therefore, researchers can state that the sub-stands where intensive silviculture is applied are within an appropriate range. In addition, this regeneration can be complemented with planting.

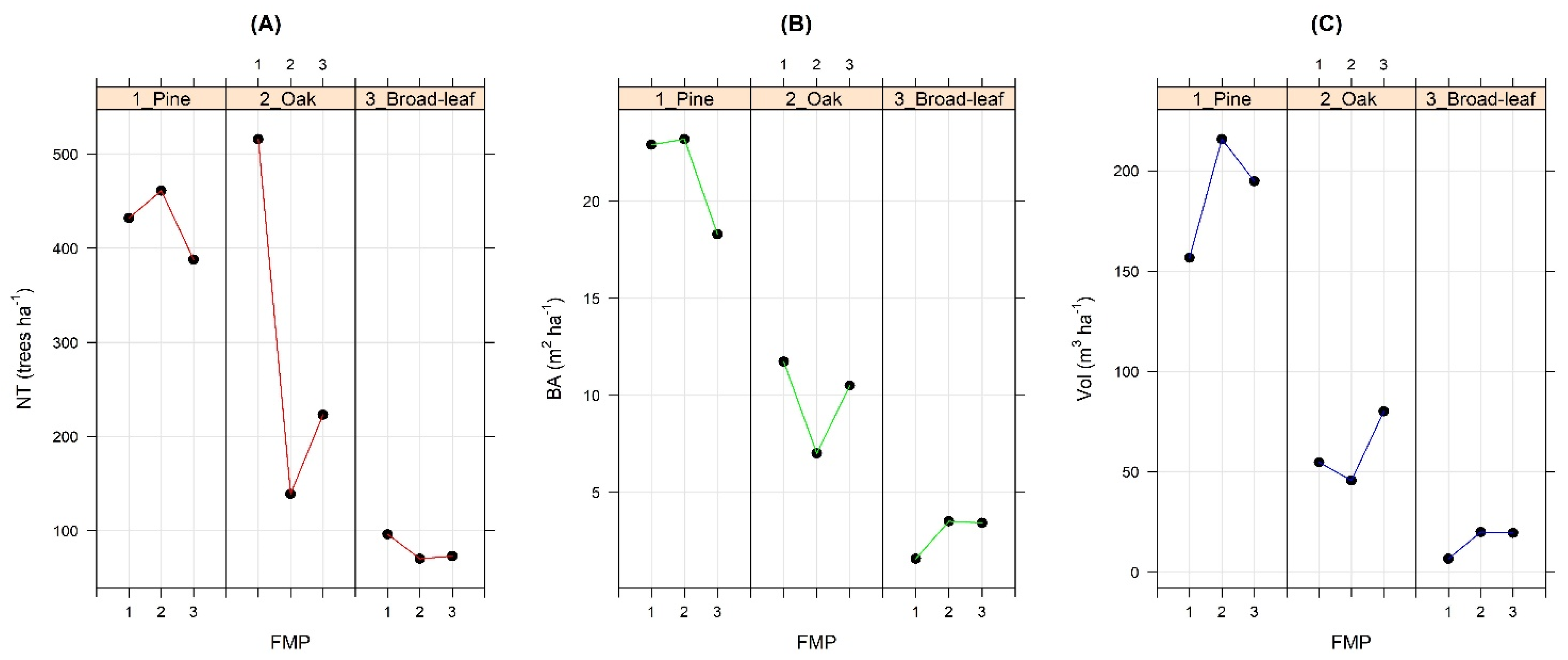

In the G0107 sub-stand (18.01 ha) of FMP1, the single-tree selection silvicultural treatment was applied, while the treatment in the two later FMPs was strip clearcutting. In FMP1, there was a larger stock of oaks; however, in FMP2, they were significantly reduced, favoring the growth of pine (Figure 4A), despite the fact that, in FMP1, the dominance in NT was oak, while BA (Figure 4B) and Vol (Figure 4C) were higher in pine. The different samplings for sub-stand G0107 showed a different dominant species; in the first, second, and third samplings, the reported species were Pinus teocote, Pinus leiophylla Schiede ex Schltdl. & Cham., and Pinus patula, respectively. This reveals the species diversity in each sub-stand, since the application of silvicultural treatments modifies the conditions of diversity and abundance of the tree species present [22][26][30]. This situation is not only present in intensive methods; Solís-Moreno et al. [39] recorded that, in the forests of Durango, Mexico, the single-tree selection method also decreased tree diversity, since cuts were concentrated on only the Pinus genus with the best individual characteristics. Meanwhile, Yoshida et al. [40], in a forest managed with the single-tree selection method in Hokkaido, Japan, found a decrease in structural values and significant elements for biodiversity, such as large trees.

Figure 4. Comparison of number of trees (NT) (A), basal area (BA) (B), and volume (Vol) (C) of the three forest management plans (FMPs) in the G0107 sub-stand.

In one study, Leyva-López et al. [41] found no differences in tree diversity between an area with another without forest management, and, although management could change the spatial structure of the forest, the species diversity was maintained. Ramírez-Santiago et al. [42] reported that non-intervened forests present greater diversity than managed forests, and that the mean annual increment in volume is similar in forests with seed-tree and group selection methods to a forest without management. Furthermore, Martínez-Cervantes [43] showed that, in the Ixtlán de Juárez forests, a great richness and diversity is maintained in areas with intensive forest management. In the G0107 sub-stand (Figure 4), the Simpson index (1-D) of 0.71 reveals a high biodiversity, mentioning that the species richness is concentrated in the genera Pinus and Quercus.

In the H0202 sub-stand (Figure 5) with 48.63 ha, the dominant species was Pinus patula. The first intervention was carried out by means of single-tree selection method, while the last two FMPs involved strip clearcutting; in the three forest inventories, the number of pine trees was similar. The number of oak and broadleaf trees varied greatly in the three forest inventories (Figure 5A). The total count of trees per hectare differed greatly: 1047 trees·ha−1, 532 trees·ha−1, and 699 trees·ha−1 in the first, second, and third inventories. This is because in the first intervention thinning and loggings were intensive and gave priority to the Pinus genus.

Figure 5. Comparison of number of trees (NT) (A), basal area (BA) (B), and volume (Vol) (C) of the three forest management plans (FMPs) in the H0202 sub-stand.

The volume of pine increased (Figure 5C) successively in the inventories of FMP2 and FMP3, respectively, while that of oak decreased from FMP1 to FMP2 but recovered in FMP3. The difference in volume of other broadleaf trees was small, although the NT decreased considerably. The increments also depend on the silvicultural treatment that is being applied, which directly influences growth in terms of both diameter and height, due to the conditions acquired in the forest site. In this case, the single-tree selection method was changed to strip clearcutting.

For pine–oak forests in Chihuahua, managed with the silvicultural development method (MDS), Núñez-López et al. [44] determined that, from the second measurement, the averages in BA, biomass, and growth produced were greater in the area with applied silvicultural treatments than in areas without management, verifying that the increases were larger in the forests where good silvicultural management was applied. This also depends on the site quality and its topographic and climatological conditions, in addition to the scheduled thinning regime, age of the stand, and the status of the residual trees [45].

Stand age also influences growth and increment. Santiago-García et al. [46] suggested that, in young stands of Pinus patula, thinning intensity should generally be strong and that the prescription should be based on stand density management diagrams, which would allow for better forest management. Intermediate cuttings allow productivity of the stand to increase. It has been shown that thinning and pruning can increase the value of the final harvest by increasing the merchantable volume, size, and wood quality [47].

Species dominance depends on the silvicultural treatment applied, in addition to the characteristics of the species in responding to natural regeneration and the conditions of the forest site. In the study area, even when different treatments were applied or a combination of the single-tree selection method with the strip clearcutting method was applied in the same sub-stand, the dominant species changed often or, in several cases, remained stable, as in the case of Pinus patula, because its relative abundance was higher [28]. This is also attributed to the fact that artificial regeneration was carried out in the community, and this was one of the main species produced in the nursery, because of its morphological characteristics and broad adaptation capacity [29][35]. In most of the sub-stands, the dominance of pines over oaks was noticeable; the treatments changed in each sub-stand, and each one had a different trend.

The results of the analysis carried out at the sub-stand level in the forests of Ixtlán de Juárez made it possible to demonstrate that, under community forest management and with greater management intensity, better productivity characteristics were obtained in volume and basal area, without affecting the richness of species.

References

- Comisión Nacional Forestal El Sector Forestal Mexicano en Cifras 2020. Available online: http://www.gob.mx/conafor/documentos/el-sector-forestal-mexicano-en-cifras-2020 (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- Torres-Rojo, J.M.; Moreno-Sánchez, R.; Mendoza-Briseño, M.A. Sustainable forest management in Mexico. Curr. For. Rep. 2016, 2, 93–105.

- de los Santos-Posadas, H.M.; Valdez-Lazalde, J.R.; Torres-Rojo, J.M. Chapter 23-San Pedro El alto community forest, Oaxaca, Mexico. In Forest Plans of North America; Siry, J.P., Bettinger, P., Merry, K., Grebner, D.L., Boston, K., Cieszewski, C., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 199–208. ISBN 978-0-12-799936-4.

- Madrid, L.; Núñez, J.M.; Quiroz, G.; Rodríguez, Y. La propiedad social forestal en México. Investig. Ambient. 2009, 1, 179–196.

- Frey, G.E.; Cubbage, F.; Holmes, T.P.; Reyes-Retana, G.; Davis, R.R.; Megevand, C.; Rodríguez-Paredes, D.; Kraus-Elsin, Y.; Hernández-Toro, B.; Chemor-Salas, D.N. Competitiveness, certification, and support of timber harvest by community forest enterprises in Mexico. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 107, 101923.

- Mathews, A.S. Mexican forest history. J. Sustain. For. 2002, 15, 17–28.

- Food and Agriculture Organization Estado y Tendencias de La Ordenación Forestal En 17 Países de América Latina Por Consultores Forestales Asociados de Honduras (FORESTA). Documentos de Trabajo Sobre Ordenación Forestal; Documento de Trabajo FM/26; Servicio de Desarrollo de Recursos Forestales, Dirección de Recursos Forestales, FAO, Roma. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/j2628s/J2628S13.htm#P1316_206954 (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- Moeliono, M.; Thuy, P.T.; Bong, I.W.; Wong, G.Y.; Brockhaus, M. Social Forestry-why and for whom? A comparison of policies in Vietnam and Indonesia. For. Soc. 2017, 1, 78–97.

- Cedeño Gilardi, H.; Pérez Salicrup, D.R. La Legislación Forestal y Su Efecto En La Restauración En México. Instituto Nacional de Ecología y Cambio Climático. Available online: http://www2.inecc.gob.mx/publicaciones2/libros/467/cedenoyperez.html (accessed on 10 June 2021).

- Aguirre-Calderón, O.A. Manejo Forestal en el Siglo XXI. Madera Bosques 2015, 21, 17–28.

- Rodríguez-Zúñiga, J.; González-Guillén, M.D.J.; Valtierra-Pacheco, E. Las empresas forestales comunitarias en la región de la Mariposa Monarca, México: Un enfoque empresarial. Bosque (Valdivia) 2019, 40, 57–69.

- Bray, B.; Merino-Pérez, L. The rise of community forestry in Mexico: History, concepts, and lessons learned from twenty-five years of community timber production. In A Report in partial fulfillment of Grant; The Ford Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2002.

- Wright, D.A.; Leighton, A.D. Forest utilization in Oaxaca. J. Sustain. For. 2002, 15, 67–79.

- Bray, D.B.; Merino-Pérez, L. La Experiencia de las Comunidades Forestales en México: Veinticinco Años de Silvicultura y Construcción de Empresas Forestales Comunitarias; Instituto Nacional de Ecología: Distrito Federal, Mexico, 2004; ISBN 978-968-817-656-6.

- TIASA. Programa de Manejo Forestal Para El Predio de La Comunidad de Ixtlán de Juárez, Oaxaca; TIASA: Oaxaca, Mexico, 1993.

- Ganz, D.J.; Burckle, J.H. Forest utilization in the Sierra Juarez, Oaxaca, Mexico. J. Sustain. For. 2002, 15, 29–49.

- Asbjornsen, H.; Ashton, M.S. Community forestry in Oaxaca, Mexico. J. Sustain. For. 2002, 15, 1–16.

- Chapela, F. Chapter 5: Indigenous Community Forest Management in the Sierra Juárez, Oaxaca. In The Community Forests of Mexico: Managing for Sustainable Landscapes; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 2005; pp. 89–110. ISBN 978-0-292-79692-8.

- Chaudhary, A.; Burivalova, Z.; Koh, L.P.; Hellweg, S. Impact of forest management on species richness: Global meta-analysis and economic trade-offs. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23954.

- Machar, I.; Simon, J.; Rejsek, K.; Pechanec, V.; Brus, J.; Kilianova, H. Assessment of forest management in protected areas based on multidisciplinary research. Forests 2016, 7, 285.

- Liang, J.; Crowther, T.W.; Picard, N.; Wiser, S.; Zhou, M.; Alberti, G.; Schulze, E.-D.; McGuire, A.D.; Bozzato, F.; Pretzsch, H.; et al. Positive biodiversity-productivity relationship predominant in global forests. Science 2016, 354, aaf8957.

- Poudyal, B.H.; Maraseni, T.; Cockfield, G. Impacts of forest management on tree species richness and composition: Assessment of forest management regimes in Tarai landscape Nepal. Appl. Geogr. 2019, 111, 102078.

- Pretzsch, H.; Block, J.; Dieler, J.; Dong, P.H.; Kohnle, U.; Nagel, J.; Spellmann, H.; Zingg, A. Comparison between the productivity of pure and mixed stands of Norway spruce and European beech along an ecological gradient. Ann. For. Sci. 2010, 67, 712.

- Pretzsch, H.; Bielak, K.; Block, J.; Bruchwald, A.; Dieler, J.; Ehrhart, H.-P.; Kohnle, U.; Nagel, J.; Spellmann, H.; Zasada, M.; et al. Productivity of mixed versus pure stands of oak (Quercus petraea (Matt.) Liebl. and Quercus robur L.) and European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) along an ecological gradient. Eur. J. For. Res. 2013, 132, 263–280.

- Schall, P.; Ammer, C. How to quantify forest management intensity in Central European forests. Eur. J. For. Res. 2013, 132, 379–396.

- Dieler, J.; Uhl, E.; Biber, P.; Müller, J.; Rötzer, T.; Pretzsch, H. Effect of forest stand management on species composition, structural diversity, and productivity in the temperate zone of Europe. Eur. J. For. Res. 2017, 136, 739–766.

- Soto Cervantes, J.A.; Padilla Martínez, J.R.; Domínguez Calleros, P.A.; Carrillo Parra, A.; Rodríguez Laguna, R.; Pompa García, M.; García Montiel, E.; Corral Rivas, J.J. Effect of Four Silvicultural Treatments on Timber Production in a Forest in Durango. Rev. Mex. Cienc. For. 2021, 12, 56–80.

- Santiago-García, W.; Jacinto-Salinas, A.H.; Rodríguez-Ortiz, G.; Nava-Nava, A.; Santiago-García, E.; Ángeles-Pérez, G.; Valle, J.R.E.-D. Generalized height-diameter models for five pine species at Southern Mexico. For. Sci. Technol. 2020, 16, 49–55.

- Servicios Técnicos Forestales de Ixtlán de Juárez. Programa de Manejo Forestal Para El Aprovechamiento y Conservación de Los Recursos Forestales Maderables de Ixtlán de Juárez. Ciclo de Corta 2015-2024; Servicios Técnicos Forestales de Ixtlán de Juárez: Oaxaca, Mexico, 2015.

- Castellanos-Bolaños, J.F.; Treviño-Garza, E.J.; Aguirre-Calderón, O.A.; Jiménez-Pérez, J.; Velázquez-Martínez, A. Diversidad arbórea y estructura espacial de bosques de pino-encino en Ixtlán de Juárez, Oaxaca. Rev. Mex. Cienc. For. 2010, 1, 39–52.

- Ramírez Santiago, R. Efectos de la Aplicación de dos Métodos de Regeneración Sobre la Estructura, Diversidad y Composición de un Bosque de Pino-Encino en la Sierra Juárez de Oaxaca, México. Master’s Thesis, Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigaciones y Enseñanza (CATIE), Turrialba, Costa Rica, 2006.

- Ruiz-Aquino, F.; Ruiz-Ángel, S.; Santiago-García, W.; Fuente-Carrasco, M.E.; Sotomayor-Castellanos, J.R.; Carrillo-Parra, A. Energy characteristics of wood and charcoal of selected tree species in Mexico. WOOD Res. 2019, 64, 71–82.

- Pérez-Alavez, Y.; Rodríguez-Ortiz, G.; Santiago-García, W.; Campos-Angeles, G.V.; Valle, J.R.E.-D.; Martin, M.P. Effect of thinning intensity on litterfall biomass and nutrient deposition in a naturally regenerated pinus pseudostrobus lind. Forest in Oaxaca, Mexico. J. Sustain. For. 2021, 1–18.

- Santiago-García, W.; Santos-Posadas, H.M.D.L.; Ángeles-Pérez, G.; Valdez-Lazalde, J.R.; Corral-Rivas, J.J.; Rodríguez-Ortiz, G.; Santiago-García, E. Modelos de crecimiento y rendimiento de totalidad del rodal para Pinus patula. Madera Bosques 2015, 21, 95–110.

- Santiago-García, W.; Pérez-López, E.; Quiñonez-Barraza, G.; Rodríguez-Ortiz, G.; Santiago-García, E.; Ruiz-Aquino, F.; Tamarit-Urias, J.C. A Dynamic system of growth and yield equations for pinus patula. Forests 2017, 8, 465.

- Santiago, G.E. Regeneración Natural Bajo El Método de Matarrasa En Franjas En Ixtlán de Juárez, Oaxaca. Informe Final de Residencia Profesional; Instituto Tecnológico Del Valle de Oaxaca: Nazareno, Xoxocotlán; Oaxaca, México, 2010.

- Rodríguez-Ortiz, G.; García-Aguilar, J.Á.; Leyva-López, J.C.; Ruiz-Díaz, C.; Valle, J.R.E.-D.; Santiago-García, W. Biomasa estructural y por compartimentos en regeneración de Pinus patula en áreas con matarrasa. Madera Bosques 2019, 25, 25.

- Moreno, G.D.A. La Regeneración de Pino Como Sustentabilidad Del Sistema de Manejo Integral (SIMANIN) En Tapalpa, Jalisco; INIFAP-SAGARPA: Guadalajara, México, 2001.

- Moreno, R.S.; Aguirre-Calderón, Ó.A.; Treviño-Garza, E.J.; Pérez, J.J.; Ybarra, E.J.; Corral-Rivas, J. Efecto de dos tratamientos silvícolas en la estructura de ecosistemas forestales en Durango, México. Madera Bosques 2006, 12, 49–64.

- Yoshida, T.; Naito, S.; Nagumo, M.; Hyodo, N.; Inoue, T.; Umegane, H.; Yamazaki, H.; Miya, H.; Nakamura, F. Structural complexity and ecosystem functions in a natural mixed forest under a single-tree selection silviculture. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2093.

- Leyva-López, J.C.; Velázquez-Martínez, A.; Ángeles-Pérez, G. Patrones de diversidad de la regeneración natural en rodales mezclados de pinos. Rev. Chapingo Ser. Cienc. For. Ambiente 2010, 16, 227–240.

- Santiago, R.R.; Ángeles Pérez, G.; De La Rosa, P.H.; Alcalá, V.M.C.; Escalante, O.P.; Clark-Tapia, R. Efectos del aprovechamiento forestal en la estructura, diversidad y dinámica de rodales mixtos en la Sierra Juárez de Oaxaca, México. Madera Bosques 2019, 25, 25.

- Martínez-Cervantes, E. Estructura y Dinámica de Bosques Con Manejo Forestal En Ixtlán de Juárez, Oaxaca. Forestry Engineer; Universidad de la Sierra Juárez.: Oaxaca, México, 2019.

- Núñez-López, D.; Wong, G.J.C.; Paz, P.F. Dinámica de La Producción de Biomasa Por Efecto de Las Intervenciones Silvícolas Aplicadas En Bosques Regulares Del Ejido El Largo y Anexos En Chihuahua. In Proceedings of the VI Simposio Internacional del Carbono en México, Villahermosa, México, 20–22 May 2015; p. 81.

- Del Río, M.; Calama, R.; Canellas, I.; Roig, S.; Montero, G. Thinning intensity and growth response in SW-European Scots pine stands. Ann. For. Sci. 2008, 65, 308.

- Santiago-García, W.; De los Santos-Posadas, H.M.; Ángeles-Pérez, G.; Valdez-Lazalde, J.R.; Del Valle-Paniagua, D.H.; Corral-Rivas, J.J. Self-Thinning and Density Management Diagrams for Pinus Patula Fitted under the Stochastic Frontier Regression Approach. Agrociencia 2013, 47, 75–89.

- Missanjo, E.; Kamanga-Thole, G. Effect of first thinning and pruning on the individual growth of Pinus patula tree species. J. For. Res. 2015, 26, 827–831.

More

Information

Subjects:

Forestry

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

991

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

15 Mar 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No