Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Katarzyna Serwańska-Leja | + 3768 word(s) | 3768 | 2022-02-21 03:31:46 | | | |

| 2 | Bruce Ren | + 4 word(s) | 3772 | 2022-03-14 02:12:32 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Serwańska-Leja, K. Shape of Dog's Nasal Cavity and Smell. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20508 (accessed on 01 March 2026).

Serwańska-Leja K. Shape of Dog's Nasal Cavity and Smell. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20508. Accessed March 01, 2026.

Serwańska-Leja, Katarzyna. "Shape of Dog's Nasal Cavity and Smell" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20508 (accessed March 01, 2026).

Serwańska-Leja, K. (2022, March 11). Shape of Dog's Nasal Cavity and Smell. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20508

Serwańska-Leja, Katarzyna. "Shape of Dog's Nasal Cavity and Smell." Encyclopedia. Web. 11 March, 2022.

Copy Citation

Modern dogs are the most morphologically diverse group of mammals. Numerous studies have shown that dogs and their olfactory abilities are of great importance to humans. It was found that the changes within the skull have had a significant impact on the structure of the initial sections of the respiratory system, including the turbinates of the nasal passages. Congenital defects, defined as brachycephalic syndrome, are currently a significant problem in dog breeding as they can affect animal welfare and even lead to death.

dogs

anatomy

nasal cavity

nasal conchae

brachycephalic syndrome

olfactory system

1. Introduction

As a result of artificial selection and breeding concepts, the dog population grew very quickly, and these animals began to play a significant role in people’s lives. Modern dog breeds are characterized by a great variety of their anatomical shapes and in effect exhibit various capabilities and perform many specific tasks for humans [1]. This diversity makes the domestic dog the most morphologically diversified mammal species worldwide. This fact is also true with regard to the dog’s skull shape, including the brain [2][3].

This process changed the relationship between humans and animals, leading to a new pressure on selection, absent in the case of the wolf as a protoplast of the domestic dog, which determines the animals’ response to humans and the human environment. In all domesticated animals, including predators, a decreased level of anxiety or fear in contact with humans has become the most important behavioral response change. In effect, animals exhibit a decreased level of responsiveness to external stimuli [4]. The most significant results of these changes in domesticated animals include modifications in the form and size, morphology and functions of the encephalon. Numerous studies have indicated a systematic decrease in the total size of the encephalon in domesticated animals as compared to their wild protoplasts [5][6][7][8]. In contemporary dogs, their encephalon is almost 30% smaller in comparison with that of the wolf. This reduction in size is particularly evident in the limbic system, a part of the brain partly responsible for the fight-or-flight response [9][10]. The skull shape also transformed changed in response to changes in the morphology of the encephalon. Evidence to document this thesis was provided by a well-known experiment conducted in Russia, where the process of silver fox domestication was studied for over 40 years. The study found that changes in the skull shape were correlated with the level of domestication in foxes [11].

Craniological changes also had a significant impact on the structure and physiology of the respiratory system, including turbinates in dogs and other domesticated mammals [12]. The shape of the nasal cavity is particularly significant, as many dog breeds serve humans because of the dog’s fine sense of smell. In recent decades, many scent detection studies have been performed with human, animal and electronic noses. Scent detection by animals has been addressed in studies, which all suggest similar or even superior accuracy compared to standard diagnostic methods [13]. These factors make the dog a highly sensitive real-time olfactive detector.

The highly sensitive sense of smell in dogs is based on several aspects. First, the dog’s ability to detect scents relies on its acute sensitivity when distinguishing individual scents. Secondly, for the dog, even a very low concentration of some substances in the air is sufficient to detect scents. Finally, the dog distinguishes a wider spectrum of scents than is the case with other mammalian species. In other words, dogs are able to analyze more chemical substances present in the air than most other animals [14].

2. Functional Anatomy of Smell

From the very beginning probably, the extraordinary olfactory capacity of dogs has been used by humans to identify and recognize odors [15]. With their approx. 300 million olfactory receptors (humans only have 5–6 million), dogs can detect smells that seem unfathomable to humans. Dogs have olfactory receptors much more sensitive than humans, which is why they are attracted to new and interesting odors (neophilia) [16]. It has been proven that their ability to detect odorants is as much as 10,000–100,000 times that of the average human, with the lower limit of detection in canines being one part per trillion [17].

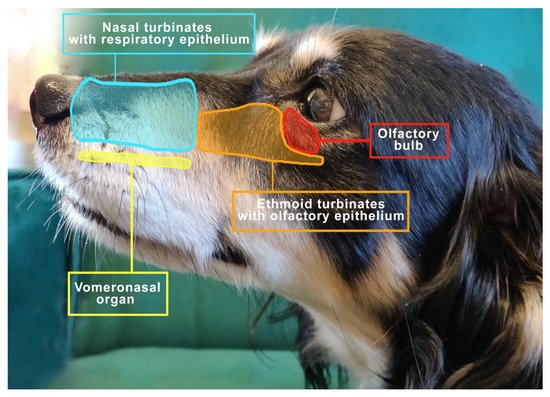

The important elements of the olfactory system include the nasal cavity, the turbinates covered with the olfactory epithelium with receptors and the vomeronasal organ (VNO) [18], as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The view to the left of the mesocephalic dog’s head shows the distribution of important structures related to respiration and smell.

The turbinates contribute to an increase in the area lined by the mucosa. However, its total surface may be influenced by the size and shape of the dog’s mouth [19]. The nasal turbinates protrude from the side walls of the nasal cavity and contain the venous network; thus 5–15% of air inhaled by dogs is redirected to them [20].

As air is inhaled, it first enters the nasal turbinates, where a small number of olfactory receptor neurons are located, then flows into the ethmoid turbinates and paranasal sinuses and subsequently toward the pharynx and larynx [21]. The turbinate obstruction alters the way air flows into the olfactory fissure, which in turn affects the sense of smell. The swelling of the turbinate epithelium decreases with exercise, hypercapnia and increased sympathetic tone, while it increases with exposure to cold air and chemical irritants, as well as hypocapnia and increased parasympathetic tone [22].

The VNO (also called Jacobson’s organ) lies along the right-cephalic side of the nasal septum, is symmetrical on both sides and functions as an additional site for odor detection [23][24]. The VNO sensory neurons detect chemical signals that cause behavioral and/or physiological changes [25]. Dennis’s observations in 2003 were expanded and confronted by Salazar et al. in a study of the morphology and physiology of the vomeronasal system in dogs. The VNO of dogs contains both types of epithelia, i.e., receptor and non-receptor epithelium, which are structurally different in the types of nerve fibers and integrated cells [26]. The function of the VNO is to detect a wide range of chemicals including fragrances, in particular pheromones [27][28], and it is believed to play an important role in social behavior and reproduction in dogs. Studies indicate that MRI is the most appropriate imaging technique for VNO visualization, allowing for precise evaluation of soft tissues. This seems important as it has been shown that disturbances in VNO structure may influence behavioral changes in animals. It has been disclosed that VNO sensory epithelial inflammation may show a correlation with the occurrence of intraspecific aggression [29]. In addition, studies on cats indicate a possible association of VNO epithelial inflammation with intraspecific aggressive behavior. Inflammation can weaken the functionality of the epithelium, causing changes in intra-species communication, possibly by reducing the action and perception of chemical communication, which significantly affects behavioral disturbances in cats [30].

An interesting behavior related directly to the VNO is the flehmen reflex. Some species of animals, when taking pheromones from the environment, show a characteristic behavior, the so-called flehmen reflex, involving the curl of the upper lip and the elevation of the nostrils, especially well expressed in horses. Such a reflex improves the movement of inhaled pheromones toward the olfactory bulb [31]. The typical flehmen reflex is not observed in dogs and cats because their upper lips are too rigid and firmly fixed via the frenulum to permit this type of movement. These animal species exhibit different attitudes of behavior, namely they assume a position with an upright head and neck, which they stretch forward for a short time [32]. In cats, an open mouth is observed, then the cat licks the nose area and stares motionlessly into the distance, while the lip remains raised all the time [33]. In dogs, there is a rapid retraction of the tongue toward the incisal papilla which probably also aids the perception of pheromones [32].

Compared to humans, dogs have a much larger olfactory area with an olfactory epithelium that can recognize many more odors. The sensory area occupies more than 30% of the nasal cavity in dogs [34]. Therefore, different breeds of dogs are successfully used for comparative research in olfaction. Not only are they particularly sensitive to fragrances [17], they also have the ability to localize the odor perfectly, even in the presence of a significant background odor, which is possibly thanks to the larger size of their nasal cavity compared to other species [34] and a unique airflow path affected by sniffing. The ability to find the source of the odor, even in the presence of competing odors, makes the tracking dog a key partner in many military operations and police work, e.g., in search and rescue operations [35]. Numerous studies have established that dogs and their olfactory ability are of great importance to medicine. Thanks to their special skills, they successfully detect infectious diseases, neoplasms and metabolic diseases such as diabetes [36]. Recent studies also confirm that dogs can be helpful in detecting COVID-19 [14][37].

3. The Nose Structure and Airflow Routes in Animals

The head is the most important and highly specialized part of the body because it contains the brain and vital sense organs related to hearing, sight and smell. In addition to these activities, the nasal cavity also has an extremely important thermoregulatory function. It modifies properties of the inhaled air before it reaches further parts of the respiratory tract. It is heated by passing through the highly vascular surface of the mucosa and moisturized in the process of evaporation of tears and nasal secretions [38].

The cranial cavity is separated from the nasal cavity by a perforated plate called the lamina cribrosa ethmoid plate, which is a part of the ethmoid bone (os ethmoidale). This bone lies on the border of the facial part of the viscerocranium and the cerebral part, i.e., the neurocranium. The nasal cavity (cavum nasi) covers most of the face. In the complex of bones bounding the nasal cavity, the maxilla (maxilla) is the largest, which significantly enlarges the initial airways, also forming the maxillary sinus [39]. However, already at this stage, it needs to be stated that in dogs this sinus is minimized only to the maxillary recess (recessus maxillaris), limited dorsally by the nasal bone, laterally by the maxillary and incisor bones and ventrally through the palatine process of the maxilla as well as the incisors and the palatine bone. The incisal bone divides the entrance of the nasal cavity and the roof of the palate at the beginning of the skull. In turn, the nasal bone is long and thin, and it is located on the dorsal part of the facial skeleton. Its length may vary depending on the dog breed. The nasal cavity is also divided by the nasal septum (septum nasi) into the right and left nasal cavities. This septum is mostly made of cartilage tissue, and it ossifies in the caudal part, forming the vertical plate of the ethmoid bone [40]. The blade, in turn, forms the caudal-ventral part of the nasal septum. The sagittal part is built by two thin lateral layers of bone plates that adhere ventrally and form the cartilaginous part of the nasal septum in the initial part and the vertical plate of the ethmoid bone (the bony part of the nasal septum) [22].

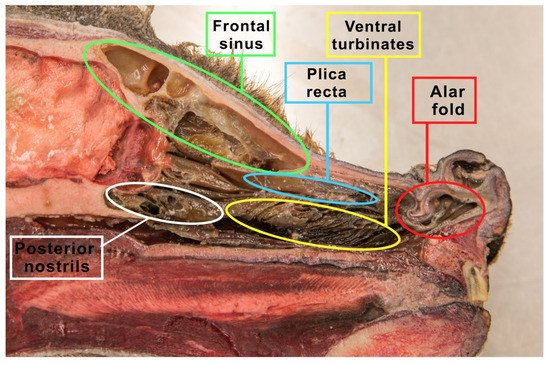

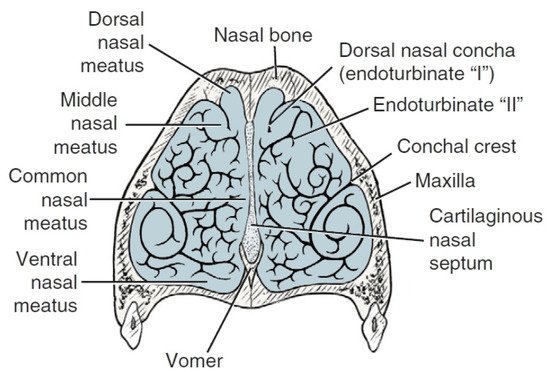

The space within the nasal cavity is significantly limited by the nasal conchae (conchae nasales) attached to its walls, which are delicate curved bone structures covered with mucosa that support the sense of smell [40]. The nasal turbinates are characterized by an extremely complicated pattern as indicated in Figure 2. Topographically, the researchers can distinguish the caudal system building the ethmoid labyrinth (labyrinthus ethmoidalis), as well as the nasal system, which consists of extensive nasal conchae-dorsal, ventral and middle, being the smallest (Figure 3). The numerous ethmoid turbinates (ethmoturbinalia) are separated by ethmoid ducts, which are especially complicated in animals, in which the sense of smell plays an important role [39].

Figure 2. The figure shows a sagittal section of the wolf’s head. The nasal turbinates, the ethmoid labyrinth (made of the inner and outer ethmoid turbinate), nasal passages and the frontal sinus were prepared.

Figure 3. Cross-section of ventral nasal turbinates in dogs. Based on [21].

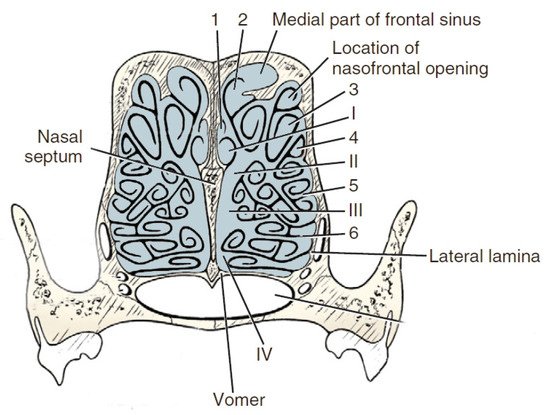

Anatomically the researchers can distinguish the outer ethmoid turbinate (ectoturbinalia), the inner ethmoid turbinate, also known as the dorsal turbinate of the nose (endoturbinale/concha nasalis dorsalis), and the first, second, third and fourth inner ethmoid turbinates (endoturbinale I, II, III, IV) (Figure 4). The first ethmoid turbinate is the most dorsal; it is the longest and farthest in the nasal cavity. It forms the skeleton of the dorsal turbinate. The second ethmoid turbinate is located next to the first and is the skeleton of the middle turbinate. Turbinates III and IV are small in most species. The exception is the dog, in which these turbinates are very well formed. The internal ethmoid turbinates are the medial and dorsal nasal turbinates. The outer turbinates are arranged in one row, with the exception of the horse, where they form two rows [40].

Figure 4. Transverse section of the ethmoturbinates in dogs. I, II, III, IV—endoturbinates; 1, 2, 3, 4—ectoturbinates. Based on [21].

The dorsal nasal turbinate (concha nasalis dorsalis) is a curved bone lamina built into the ethmoid crest [41]. It is the longest in comparison to the other turbinates. It extends from the ethmoid plate to the nasal vestibule. Ventral nasal concha (concha nasalis ventralis), attached to the jaw through a turbinate crest located in the nasal cavity [42] and the hard palate, models the course of the nasal passages and the distort of the front part of the nasal cavity. The ventral surface of the nasal bone is covered with mucosa, forming the dorsal nasal passage [43]. They are products of delicate tubular bone plates, the shape and structure of which depend on the location or species. In the nasal part, the bone plates do not curl up and are not connected. Caudally, the researchers can see that they curl in such a way that the pinnae touch each other or the side walls of the nasal cavity, thus closing the space belonging to the area of the paranasal sinuses. In the cross-section of the head in the transverse plane, it can be seen that these slits, plates and wiroures ourin the croourss-section form the letter “E” [39]. The nasal cavities include all the three nasal passages—meatus nasalis dorsalis, meatus nasalis medius and meatus nasalis ventralis—formed by the nasal turbinates [44]. These structures meet near the septum of the nose to form the common nasal duct (meatus nasalis communis). The dorsal nasal passages between the vault of the nasal cavity and the dorsal nasal turbinate are observed. They extend to the ethmoid bone and terminate. It is the direct pathway of the inhaled air toward the olfactory region of the nasal cavity. It is also called the olfactory nasal passage, as it terminates in the olfactory region of the nasal cavity. The middle nasal passage is responsible for the connection of the nasal cavity with the paranasal sinuses; thus the term sinus nasal passage is also used. It extends between the dorsal and ventral turbinates and separates in the caudal segment because the middle nasal turbinate is located there. The common (medial) nasal passage lies in the medial plane between the nasal septum and the turbinates, reaching the canopy of the bottom of the nasal cavity. Together with the abdominal (respiratory) duct, they create a path for the air passing toward the nasopharynx [39].

4. Brachycephalia, the Brachycephalic Syndrome and Anatomical Changes in the Nose Balances in Dogs

Considering the large number of dog breeds, the researchers know that morphological differences of these breeds are highly varied and easily discernible. This is one of the reasons why in cynology three types of dog breeds were established: dolichocephalic, mesocephalic and brachycephalic [2]. The term “brachycephalic” means literarily “short, wide-headed” [23]. Brachycephalic breeds are easily recognized by their shortened nose and widely spaced, shallower eye sockets than in the other types of dogs. In dogs, a number of craniofacial anomalies can contribute to brachycephaly, including reduction in bone length, chondrodysplasia of the base of the skull and changes in the position of the palate relative to the base of the skull [45]. According to many studies, these dogs may suffer from the brachycephalic syndrome and respiratory problems, among others.

Brachycephaly is associated with the modification of the skeleton and skull [46]. This results in a distinctive short and very often flattened dorso-ventral snout. This is a result of deliberate efforts by breeders to select dogs for breeding so that they develop local chondrodysplasia and generate individuals with an even more shortened facial skeleton [47][48]. In recent years, there has been a significant increase in the popularity of brachycephalic breeds. According to the British Kennel Club, registrations of French bulldogs increased by 3104%, pugs by 193% and English bulldogs by 96%. Similarly in Australia, according to the ANKC, in the period of 1987–2017, there was an upward trend in the registration of French bulldogs by 11.3% (percentage of the total number of purebred dog registrations), pugs by 320% and English bulldogs by 324% [49]. However, it is impossible not to mention the other side of the coin. In 2014, the Dutch government passed a law prohibiting the breeding of dogs with short mouths with features that may adversely affect the health of dogs and their descendants. Therefore this law applies to all races that have an exaggerated appearance. However, it is not about forbidding the reproduction of selected breeds altogether. Dutch law aims to eliminate from further breeding only those individuals whose physique may cause suffering or serious discomfort to dogs [50].

Despite the growing popularity of these breeds worldwide [51][52][53], it has been shown that the morphological changes are relatively serious and are associated with hereditary head and neck disorders [51][54]. In brachycephalic dogs, the shortened base of the skull also includes a reduction in the length of the nasopharynx [55]. All the congenital anomalies and anatomical abnormalities observed in these breeds, in particular those affecting the respiratory system, but also digestive, eyes, skin and other systems, are described jointly by one term: the brachycephalic syndrome.

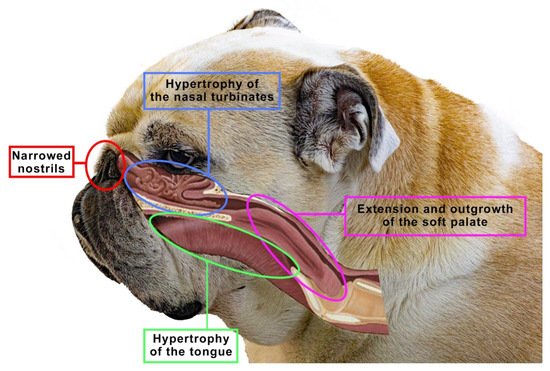

The brachycephalic syndrome, also known as the obstructive brachycephalic respiratory syndrome (BAOS or BAS), is a fairly well-described ongoing process of anatomical and functional disorders of the respiratory and digestive systems [53][56]. Dogs diagnosed with BAOS tend to have severe breathing problems as a consequence of the anatomical deformities in the head [57][58]. The basic conditions of the brachycephalic syndrome include congenital anatomical abnormalities such as narrowed nostrils, an elongated soft palate, hypoplastic trachea and nasopharynx and changes in the structure of the nasal turbinates. Figure 5 shows an English bulldog with manifestations of the brachycephalic disorders typical of this type of breed, classified as the brachycephalic syndrome.

Figure 5. The figure shows an English bulldog. Visible here are signs that are typical for many brachycephalics, classified as the brachycephalic syndrome, such as narrowed nostrils, hypertrophy of the tongue, soft palate or nasal turbinates. Based on [10].

The above-mentioned anatomical abnormalities modified the physiology of the respiratory system in brachycephalic breeds [59]. Primary abnormalities such as narrowed nostrils or enlarged turbinates can lead to a significant increase in breathing effort to overcome airway resistance [60]. Chronic airway obstruction in brachycephalic dogs can lead to secondary lesions, including soft palate hypertrophy, laryngeal edema, laryngeal sac degeneration and laryngeal collapse [61].

Clinically, dogs show signs of respiratory distress such as severe dyspnoea, wheezing, coughing, snoring, reluctance to exercise, increased breathing effort, hyperthermia and even collapse [62]. This condition occurs because, despite a marked reduction in the length of the craniofacial skeleton [55], the structures of the soft tissues of the oral cavity and nasal cavity (e.g., soft palate, tongue, tonsils) are not proportionally reduced [63].

In addition to the BAS elements noted above, the authors have observed and documented the presence of the nasal turbinates extending caudally from the nasal cavity to the nasopharynx [44]. The unique anatomy of the skull in the brachycephalic breeds may explain the development of turbinate hypertrophy. The nasal turbinates, along with most of the other bones in the skull, originate from the ectoderm, while the other bones in the body come from the mesoderm. Some bones are formed by ossification on a membranous substrate and tend to form close to the structures they contain [43]. In contrast, cartilage bones continue to grow and ossify only after the end of pregnancy. They are less plastic and tend to grow fully. The nasal turbinates are formed precisely as a result of endochondral ossification, and thus they can grow beyond their immediate vicinity [64][65]. Therefore, in the brachycephalic breeds, the ethmoid turbinates may show a tendency to significantly overgrow into the nasopharynx due to the limited space in the already ossified nasal cavity [44]. The resulting contact between the mucosa-covered turbinates hinders the flow of air through the nose [54]. This is not a normal structure of the initial airway, and studies have shown that turbinate hypertrophy to the pharynx is a common condition in brachycephalic dogs [44]. Clinical cases with hypertrophy and deformation of the nasal turbinates toward the pharynx have been reported many times, while the influence of these anatomical anomalies on the occurrence of BOAS is not fully understood. The most common brachycephalic breeds around the world are pugs, English bulldogs and French bulldogs. Both pugs and French bulldogs are classified as extremely brachycephalic dogs, but there are differences in these breeds concerning clinical signs and skull structure. In pugs, turbinate hypertrophy is a particularly common disease because, despite the shortening of the facial skeleton, it does not shorten the turbinates [66]. It is assumed that turbinate hypertrophy affects up to 21% of these dogs. That is why it is so important to evaluate the nasopharynx for turbinate hypertrophy in all brachycephalic dogs using various methods, including upper respiratory endoscopy [44]. Several other diagnostic methods are also used to assess the anatomical and dynamic changes associated with BOAS, including radiography and computed tomography (CT) [67], while craniometric measurements are also analyzed. In particular, CT allows the obtained data to be reformatted into multiplanar and three-dimensional images. This allows the entire initial airway and throat structures to be visualized. To date, few studies have been published on the CT assessment of the anatomy of the initial airways in brachycephalic dogs, none of which have looked at the measurement of hypertrophied turbinates in specific breeds such as the pug or the bulldog [65][68][69]. These few studies suggest that further characterization and studies of nasal turbinates and their hypertrophy are important. For this purpose, it is worth using computed tomography and three-dimensional imaging tests, which can additionally help characterize the structure of the nasal turbinates and their anatomical anomalies. Research evaluating the prevalence among the breeds as well as the contribution of these structures to the increase in airway resistance and clinical symptoms of the brachycephalic syndrome is warranted. Further anatomical and histological observations in this direction are recommended, which shows that this topic needs to be investigated further, in more detail [44].

References

- Lord, K.; Schneider, R.A.; Coppinger, R. In The Origins and Evolution. In The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behaviour and Interactions with People; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016; Volume 4, pp. 21–50.

- Schoenebeck, J.J.; Ostrander, E.A. The genetics of canine skull shape variation. Genetics 2013, 193, 317–325.

- Sablin, M.; Khlopachev, G. The earliest ice age dogs: Evidence from Eliseevichi. Curr. Anthropol. 2002, 43, 795–799.

- Coppinger, R.; Coppinger, L. Dogs: A Startling New Understanding of Canine Origin, Behaviour, and Evolution; Crosskeys: London, UK, 2004.

- Plogmann, D.; Kruska, D. Volumetric comparison of auditory structures in the brains of european wild boars (sus scrofa) and domestic pigs (sus scrofa f. dom.). Brain Behav. Evol. 1990, 35, 146–155.

- Ebinger, P.; Röhrs, M. Volumetric analysis of brain structures, especially of the visual system in wild and domestic turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo). J. Hirnforsch. 1995, 36, 219–228.

- Kruska, D. The effect of domestication on brain size and composition in the mink (mustela vison). J. Zool. 1996, 239, 645–661.

- Kruska, D. Mammalian domestication and its effect on brain structure and behaviour. In Intelligence and Evolutionary Biology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1988; pp. 211–250.

- Lord, K.; Schneider, R.A.; Coppinger, R. Evolution of working dogs. In The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behaviour and Interactions with People; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016; pp. 42–66.

- Zeder, M.A. Pathways to animal domestication. In Biodiversity in Agriculture; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 227–259.

- Trut, L. Early canid domestication: The farm-fox experiment. Am. Sci. 1999, 87, 160–169.

- Schoenebeck, J.J.; Hutchinson, S.A.; Byers, A.; Beale, H.C.; Carrington, B.; Faden, D.L.; Rimbault, M.; Decker, B.; Kidd, J.M.; Sood, R.; et al. Variation of BMP3 contributes to dog breed skull diversity. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002849.

- Ghosh, S.; Jana, A.; Mahanti, B. An updated review on medical detection of dog. Asian J. Pharm. Anal. 2016, 6, 47–52.

- Kokocińska-Kusiak, A.; Woszczyło, M.; Zybala, M.; Maciocha, J.; Barłowska, K.; Dzięcioł, M. Canine olfaction: Physiology, behaviour, and possibilities for practical applications. Animals 2021, 11, 2463.

- Marchal, S.; Bregeras, O.; Puaux, D.; Gervais, R.; Ferry, B. Rigorous training of dogs leads to high accuracy in human scent matching-to-sample performance. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146963.

- Cambau, E.; Poljak, M. Sniffing animals as a diagnostic tool in infectious diseases. Clin. Microbiol. Infec. 2020, 26, 431–435.

- Walker, D.B.; Walker, J.C.; Cavnar, P.J.; Taylor, J.L.; Pickel, D.H.; Hall, S.B.; Suarez, J.C. Naturalistic quantification of canine olfactory sensitivity. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2006, 97, 241–254.

- Jezierski, T.; Ensminger, J.; Papet, L.E. Canine Olfaction Science and Law: Advances in Forensic Science, Medicine, Conservation, and Environmental Remediation; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA; Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016.

- Taherali, F.; Varum, F.; Basit, A.W. A slippery slope: On the origin, role and physiology of mucus. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2018, 123, 16–33.

- Galibert, F.; Azzouzi, N.; Quignon, P.; Chaudieu, G. The genetics of canine olfaction. J. Vet. Behav. 2016, 16, 86–93.

- Evans, H.E.; Delahunta, A.; Miller, M.E. Miller’s Anatomy of the Dog; Elsevier Pte. Ltd.: Singapore, 2016; pp. 122–218.

- Jenkins, E.K.; DeChant, M.T.; Perry, E.B. When the nose doesn’t know: Canine olfactory function associated with health, management, and potential links to microbiota. Front Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 56.

- Harper, R.J.; Furton, K.G. Biological detection of explosives. In Counterterrorist Detection Techniques of Explosives; Yinon, J., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherland, 2007; pp. 395–431.

- Trotier, D. Vomeronasal organ and human pheromones. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2011, 128, 184–190.

- Dennis, J.C.; Allgier, J.G.; Desouza, L.S.; Eward, W.C.; Morrison, E.E. Immunohistochemistry of the canine vomeronasal organ. J. Anat. 2003, 203, 329–338.

- Salazar, I.; Cifuentes, J.M.; Sánchez-Quinteiro, P. Morphological and immunohistochemical features of the vomeronasal system in dogs. Anat. Rec. 2013, 296, 146–155.

- Adams, D.R.; Wiekamp, M.D. The canine vomeronasal organ. J. Anat. 1984, 138, 771–787.

- Lee, K.H.; Park, C.; Kim, J.; Moon, C.; Ahn, M.; Shin, T. Histological and lectin histochemical studies of the vomeronasal organ of horses. Tissue Cell 2016, 48, 361–369.

- Dzięcioł, M.; Podgórski, P.; Stańczyk, E.; Szumny, A.; Woszczyło, M.; Pieczewska, B.; Niżański, B.; Nicpoń, W.; Wrzosek, M.A. MRI Features of the Vomeronasal Organ in Dogs (Canis Familiaris). Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 159.

- Asproni, P.; Cozzi, A.; Verin, R.; Lafont-Lecuelle, C.; Bienboire-Frosini, C.; Poli, A.; Pageat, P. Pathology and behaviour in feline medicine: Investigating the link between vomeronasalitis and aggression. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2016, 18, 997–1002.

- Crowell-Davis, S.; Houpt, K.A. The ontogeny of flehmen in horses. Anim. Behav. 1985, 33, 739–745.

- Pageat, P.; Gaultier, E. Current research in canine and feline pheromones. Vet. Clin. Small. Anim. 2003, 33, 187–211.

- DePorter, T.L. Use of pheromones in feline practice. In Feline Behavioural Health and Welfare; Rodan, I., Heath, S., Eds.; Saunders: London, UK, 2015; pp. 235–244.

- Barrios, A.W.; Sánchez-Quinteiro, P.; Salazar, I. Dog and mouse: Toward a balanced view of the mammalian olfactory system. Front. Neuroanat. 2014, 8, 106.

- Craven, B.A.; Paterson, E.G.; Settles, G.S. The fluid dynamics of canine olfaction: Unique nasal airflow patterns as an explanation of macrosmia. J. R. Soc. Interface 2009, 7, 933–943.

- Jendrny, P.; Schulz, C.; Twele, F.; Meller, S.; von Köckritz-Blickwede, M.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Ebbers, J.; Pilchová, V.; Pink, I.; Welte, T.; et al. Scent dog identification of samples from COVID-19 patients—A pilot study. BMC Infec. Dis. 2020, 20, 536.

- Sakr, S.; Ghaddar, A.; Sheet, I.; Eid, A.H.; Hamam, B. Knowledge, attitude and practices related to COVID-19 among young lebanese population. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 653.

- Mason, M.J.; Wenger, L.M.D.; Hammer, Ø.; Blix, A.S. Structure and function of respiratory turbinates in phocid seals. Polar. Biol. 2020, 43, 157–173.

- Dyce, K.M.; Sack, W.O.; Wensing, C.J.G. Textbook of Veterinary Anatomy, 5th ed.; Saunders: St. Louis, MO, USA; Elsevier: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2010.

- König, H.E.; Liebich, H. Anatomia zwierząt domowych. Galaktyka 2002, 1–66. (In Polsh)

- D’Arce, R.D.; Flechtmann, C.H.W. Introdução à Anatomia e Fisiologia Animal; Nobel: São Paulo, Brazil, 1989; pp. 37–39.

- Sisson, S.; Grossman, J.D.; Getty, R. Sisson and Grossman’s Anatomy of the Domestic Animal; Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1975; pp. 1377–1411.

- Gracis, M. Radiographic study of the maxillary canine tooth of four mesaticephalic cats. J. Vet. Dent. 1999, 16, 115–128.

- Evans, H.E.; Miller, M.E. Miller’s Anatomy of the Dog; Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1993; pp. 128–168.

- Huber, W. Biometrische analyse der brachycephalie beim haushund. L’Année Biol. 1974, 13, 135–141.

- Pollinger, J.P. Selective sweep mapping of genes with large phenotypic effects. Genome Res. 2005, 15, 1809–1819.

- Koch, A.D.; Arnold, S.; Hubler, M.; Montavon, M.P. Brachycephalic syndrome in dogs. Compend. Contin. Educ. Vet. 2003, 25, 48–55.

- Koch, A.D.; Wiestner, T.; Balli, A.; Montavon, M.P.; Michel, E.; Scharf, G.; Arnold, S. Proposal for a new radiological index to determine skull conformation in the dog. Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilkd. 2012, 154, 217–220.

- Fawcett, A.; Barrs, V.; Awad, M.; Child, G.; Brunel, L.; Mooney, E.; Martinez-Taboada, F.; McDonald, B.; McGreevy, P. Consequences and management of canine brachycephaly in veterinary practice: Perspectives from australian veterinarians and veterinary specialists. Animal 2018, 9, 3.

- Available online: https://www.fecava.org/news-and-events/news/dutch-prohibition-of-the-breeding-of-dogs-with-too-short-muzzles/ (accessed on 5 February 2022).

- Nickel, R.; Schummer, A.; Seiferle, E.; Sack, W.O. Respiratory system. In The Viscera of the Domestic Mammals; Springer: Cham, Germany, 1979; pp. 211–281.

- Vlaminck, L.; Crijns, C.; Gielen, I. Nasal cavity and sinuses in equines. In Proceedings of the 3rd International CT-User Meeting, Ghent, Belgium, 13–14 November 2020; pp. 148–149.

- Liu, N.C.; Oechtering, G.U.; Adams, V.J.; Kalmar, L.; Sargan, D.R.; Ladlow, J.F. Outcomes and prognostic factors of surgical treatments for brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome in 3 breeds. Vet. Surg. 2017, 46, 271–280.

- Asher, L.; Diesel, G.; Summers, J.F.; McGreevy, P.D.; Collins, L.M. Inherited defects in pedigree dogs. Part 1: Disorders related to breed standards. Vet. J. 2009, 182, 402–411.

- Packer, R.M.A.; Hendricks, A.; Tivers, M.S.; Burn, C.C. Impact of facial conformation on canine health: Brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137496.

- Wetzel, J.; Moses, P. Brachycephalic airway syndrome surgery: A retrospective analysis of breeds and complications in 155 dogs. ACVSc Coll. Sci. Week 2010.

- Lindsay, B.; Cook, D.; Wetzel, J.; Siess, S.; Moses, P. Brachycephalic airway syndrome: Management of post-operative respiratory complications in 248 dogs. Aust. Vet. J. 2012, 34, E4.

- Roedler, F.S.; Pohl, S.; Oechtering, G.U. How does severe brachycephaly affect dog’s lives? Results of a structured preoperative owner questionnaire. Vet. J. 2013, 198, 606–610.

- Lecoindre, P.; Richard, S. Digestive disorders associated with the chronic obstructive respiratory syndrome of brachycephalic dogs: 30 cases (1999–2001). Rev. Med. Vet.-Toulouse 2004, 155, 141–146.

- Meola, S.D. Brachycephalic airway syndrome. Top. Companion Anim. Med. 2013, 28, 91–96.

- Wykes, P.M. Brachycephalic airway obstructive syndrome. Probl. Vet. Med. 1991, 3, 188–197.

- Trappler, M.; Moore, K. Canine brachycephalic airway syndrome: Surgical management. Compendium 2011, 33, E1–E8.

- Pink, J.J.; Doyle, R.S.; Hughes, J.M.L.; Tobin, E.; Bellenger, C.R. Laryngeal collapse in seven brachycephalic puppies. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2006, 47, 131–135.

- Harvey, C.E. Inherited and congenital airway conditions. J. Small Anim. Pract. 1989, 30, 184–187.

- Trainor, P.A.; Melton, K.R.; Manzanares, M. Origins and plasticity of neural crest cells and their roles in jaw and craniofacial evolution. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2003, 47, 541–553.

- Creuzet, S.; Couly, G.; Douarin, N.M. Patterning the neural crest derivatives during development of the vertebrate head: Insights from avian studies. J. Anat. 2005, 207, 447–459.

- Heidenreich, D.; Gradner, G.; Kneissl, S.; Dupré, G. Nasopharyngeal dimensions from computed tomography of pugs and french bulldogs with brachycephalic airway syndrome. Vet. Surg. 2016, 45, 83–90.

- Oechtering, G.U.; Pohl, S.; Schlueter, C.; Lippert, J.P.; Alef, M.; Kiefer, I.; Ludewig, E.; Schuenemann, R. A novel approach to brachycephalic syndrome. Evaluation of anatomical intranasal airway obstruction. Vet. Surg. 2016, 45, 165–172.

- Oechtering, G.U.; Pohl, S.; Schlueter, C.; Lippert, J.P.; Alef, M.; Kiefer, I.; Ludewig, E.; Schuenemann, R. A novel approach to brachycephalic syndrome. Laser-assisted turbinectomy (LATE). Vet. Surg. 2016, 45, 173–181.

More

Information

Subjects:

Agriculture, Dairy & Animal Science

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

6.0K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

19 Apr 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No