Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Michiko Moriyama | + 1751 word(s) | 1751 | 2022-02-23 04:02:04 | | | |

| 2 | Bruce Ren | + 2 word(s) | 1753 | 2022-03-14 01:51:04 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Moriyama, M. Health-Seeking Behaviors in Mozambique. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20479 (accessed on 04 March 2026).

Moriyama M. Health-Seeking Behaviors in Mozambique. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20479. Accessed March 04, 2026.

Moriyama, Michiko. "Health-Seeking Behaviors in Mozambique" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20479 (accessed March 04, 2026).

Moriyama, M. (2022, March 11). Health-Seeking Behaviors in Mozambique. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20479

Moriyama, Michiko. "Health-Seeking Behaviors in Mozambique." Encyclopedia. Web. 11 March, 2022.

Copy Citation

In settings where traditional medicine is a crucial part of the healthcare system, providing culturally competent healthcare services is vital to improving patient satisfaction and health outcomes. Therefore, here sought to gain insight into how cultural beliefs influence health-seeking behaviors (HSBs) among Mozambicans. Participant observation and in-depth interviews (IDIs) were undertaken using the ethnonursing method to investigate beliefs and views that Mozambicans (living in Pemba City) often take into account to meet their health needs.

cultural influence

health-seeking behaviors

ethnonursing

Mozambique

1. Introduction

Despite significant advances in medical care, in Mozambique, many people still die from diseases for which effective treatments have been established. For instance, ailments such as diarrhea, pneumonia, malaria, and HIV/AIDS fall into this category [1][2]. Inappropriate healthcare-seeking behavior is one of the factors contributing to poor health outcomes, including death, in people suffering from malaria [3] and HIV/AIDS [4].

Mozambique has government healthcare services mainly based on modern medicine that are viewed as the norm and allows, in theory, all citizens to access these services. However, in practice, for most populations, some barriers remain regarding access to formal health services. Factors such as fear of mistreatment by and distrust of care providers, wariness of governments, financial constraints, and ethno-pathogenic perspectives (produced from indigenous causes, not from western medicine) of illnesses have been reported to discourage people from using conventional health services in Mozambique [5]. In addition, epidemiological data support the view that poor accessibility to health facilities and lack of adequate medical infrastructure limit access to conventional health services [6][7][8]. In these circumstances, traditional healers are often the only form of healthcare for many people, especially those living in rural areas, to meet their healthcare needs or understand the causes of their social problems [9]. However, even when conventional health services are available and accessible, some people in Africa still show a preference for traditional healers to deal with illnesses and ailments that they believe to be caused by sources such as spirits and sorcery. About 80% of African citizens, including Mozambicans, rely on traditional medicine [10][11]. The perceived failure of medical treatment, easy accessibility, low cost, familiarity, and respect for culture and dignity have also been reported as factors contributing to the preference for traditional medicine among Africans [12]. Accordingly, if public health strategies are to improve access to conventional health services, they should be based on the cultural aspects that influence health-seeking behaviors (HSBs) [13]. It is also indicated that considering the “spiritual dimension” of health is crucial for introducing a new primary healthcare system in the community [14].

Traditional medicine (TM) has existed in most African communities for hundreds of years because modern medicine was once not readily available [15][16]. Notably, many Africans believe that traditional healers can cure various ailments such as HIV/AIDS. In a study by Audet et al. that involved Mozambican people with HIV/AIDS who were on antiretroviral therapy, the majority of participants relied on traditional healers for their treatment [17]. Because the culture influences the health outcome with effects ranging from positive to negative, it is necessary to understand from a cultural perspective why some people do not choose the treatment regimens established by modern medicine.

1.1. Overview of Mozambique

1.1.1. Brief Ethnohistory

Facing the Indian Ocean, Mozambique is situated in southeastern Africa. In 2016, approximately 29 million people inhabited the country. After Vasco da Gama’s arrival in 1498, Mozambique fell under the control of Portugal [18]. After 400 years of foreign governance, the native inhabitants aspired for their independence and achieved their freedom by attacking the Portuguese administrators [19]. Despite attaining independence in 1975, secession from colonial occupation led to a civil war that greatly damaged reconstruction efforts following the war for independence [20].

However, the main ethnic groups in Mozambique are the Makua, Tsonga, Makonde, Shangaan, Shona, Sena, Ndau, and other indigenous groups. There are approximately 45,000 Europeans, and 15,000 South Asians, constituting less than 2% of the population, as well [21]. The literacy rate in Mozambique is 60.7% (male: 72.6%, female: 50.3%) [22], and more than 46% of people were living below the poverty line (USD 0.31 per day) in 2018 [23]. Regarding the religious aspect, 26.2% of citizens are Roman Catholic, 18.3% Muslim, 15.1% Zionist Christian, 27% other religions, and the remaining 13.4% did not list a religious affiliation [24]. Mozambique consists of more than 10 tribes. The official language is Portuguese. Religions and languages vary by region and tribe [25]. The health sector in Mozambique has changed throughout history. Before independence, medical facilities only served the Portuguese officers and those who lived in the capital city [26]. After independence and the civil war, the government achieved the reconstruction of the national health system. Now citizens have free access to public medical facilities under the primary healthcare system. However, access to better private facilities is limited to economically wealthy people and foreigners [26].

1.1.2. Theoretical Guide and Conceptual Framework

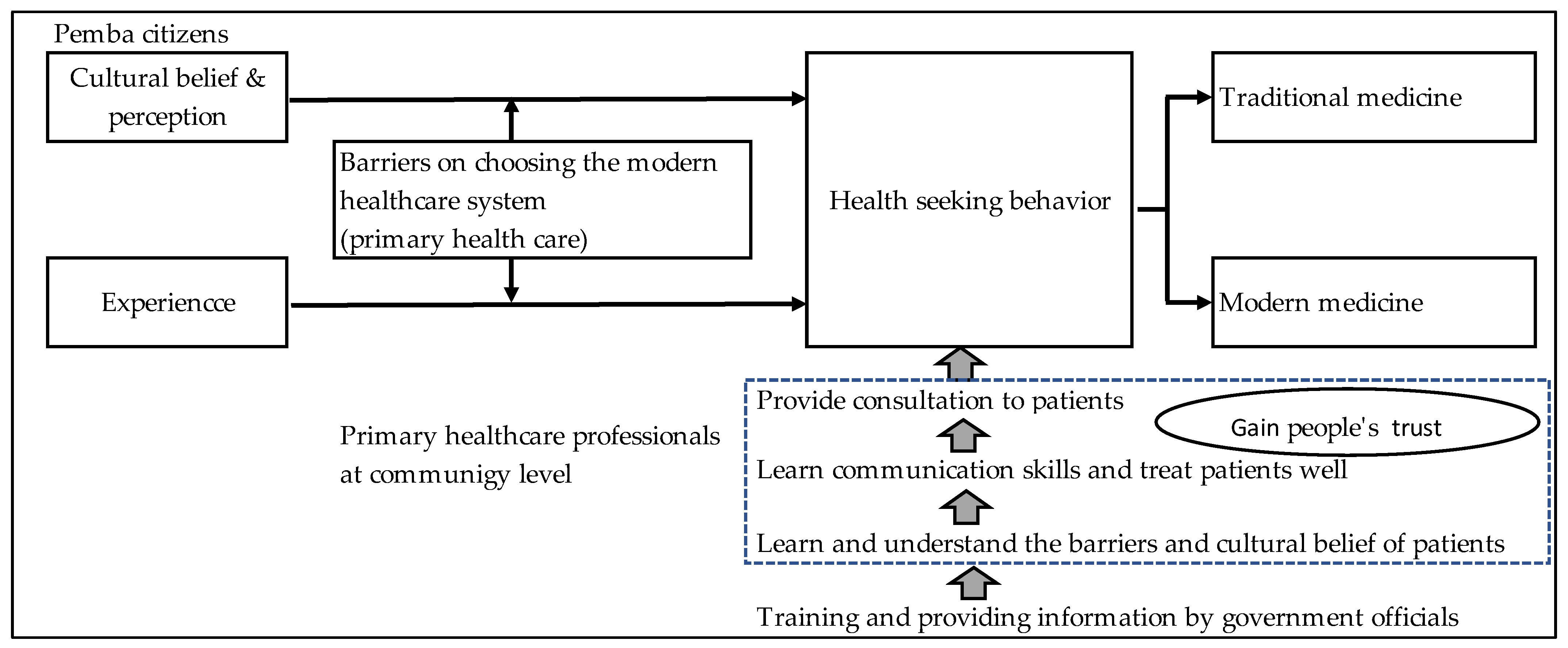

Madelaine Leininger asserted the link between providing care and culture in her book, Culture Care Diversity and Universality (CCDU), in which she explained that culture and society influence care patterns, expression and practice through environmental context, language and ethnohistory [27]. Therefore, if healthcare professionals understand the cultural influence and experience on HSBs, they can support people by helping them select an effective treatment and improve health outcomes in Mozambique (Figure 1: Conceptual framework). Accordingly, two research questions were addressed in this study: (i) What are the culturally influenced HSBs among Mozambicans living in Pemba City? and (ii) What cultural determinants influence their HSBs the most?

Figure 1. Conceptual framework.

2. Health-Seeking Behaviors in Mozambique

Overall, findings showed that people’s local perceptions reflect a belief in supernatural forces, something that is called “magic”, and supported TM as an established healthcare system; i.e., TM was the most popular first line of treatment sought by most people who were explored in this study. Similar observations have been made in earlier studies in developing countries [15][28] and they concur with the views of medical anthropologists reporting that medicine reflects the values of those who use it [29].

Research findings also revealed that the cultural beliefs and practices of Pemba citizens affected their HSBs. For instance, Pemba citizens added cultural aspects to health issues using the word “curandeirismo” in an environment that evoked strong feelings of revulsion towards Mozambique’s colonial history. Curandeiros were always close to the people, and their warm attitude earned people’s trust and satisfaction. Visiting curandeiros might be the first step in solving people’s health problems. People chose treatment from faraway traditional healers rather than nearby medical facilities. This indicated people trusted their traditional medicine more than modern medicine, which had been brought by colonial rule. They recognized that modern medicine would be an effective solution to health problems. However, they still preferred TM due to their dissatisfaction with modern medicine, including the poor interpersonal communication skills of health professionals. People applied their beliefs and views regarding the causes of diseases to HSBs that were more likely to help them meet their health needs. People have been looking for more effective treatments by navigating between modern medicine and TM. the researchers surmised that the use of TM on an equal footing with modern medicine by this population could be addressed by encouraging collaborative workshops between traditional healers and modern health providers.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recognized the importance of working with religious actors in the spiritual domain to deal with primary healthcare for changing the lifestyles and health behavior of community people [14]. Medical professionals also need to be aware of the need to collaborate with traditional healers [30]. Indeed, an educational intervention with traditional healers could promote referrals of patients to hospitals [17]. Therefore, this study suggests the need for collaboration between the two medical systems and managing the quality of TM as a health policy, in order to provide people with adequate healthcare.

Under-equipped medical facilities and health professionals’ cold attitudes and rudeness towards patients are already recognized as barriers to healthcare services [5]. As also shown in several studies [15][28][31], Pemba residents demonstrated a preference for TM to meet their health needs. Likewise, this study revealed that TM was more than just an alternative to compensate for a scarcity of medical resources. TM was often seen as a proud culture that has survived its legacy of colonization and is considered as an effective form of indigenous knowledge to deal with health problems. That is why it was often selected as the first choice among available treatment options.

African countries are multiracial, and, therefore, contain quite diverse socio-cultural backgrounds [32]. In this context, to support people in terms of their expectations regarding healthcare choices, the researchers must not fail to give sensitive consideration to cultural aspects, especially if the healthcare provider and the recipient are from different tribes. As health-care providers are not obliged to comply with all patient requests, a lack of communication and understanding of the patient’s culture by healthcare providers may not be helpful in improving health outcomes of people living in Pemba City. Leininger asserted that knowledge of cultural diversity was essential for nurses to provide appropriate care to people.

Even though Pemba City residents have recognized that medications based on modern medical treatment are likely to be the norm and effective, some have not yet realized it in practice due to conflicting relationships with health professionals. Although traditional healers are not likely to have any medical training, many communities in Africa rely on their healing practices to meet their primary healthcare needs [15][16]. However, without national regulations on TM, this reliance on TM may sometimes worsen diseases for which there is an established treatment regimen based on modern medicine. As a result, if people do not use modern healthcare, modern medicine cannot demonstrate its effectiveness, and people are likely to become even more disappointed. This is a vicious circle between modern medicine and TM, which cuts and breaks the link between the two healthcare systems.

TM’s healers gain people’s trust through their communication skills and openness to clients’ cultural backgrounds [33][34]. Such good relationships with people strengthen their recognition; for example, some people stated “we are Africans, we have our own medicine that meets our needs”. People’s cultural backgrounds vary as well as their social backgrounds and educational levels. Therefore, nurses and other healthcare professionals need advanced communication skills to serve patients from diverse cultural backgrounds. However, it is difficult for individuals to acquire such skills. The training of health professionals in Mozambique, and in Pemba City in particular, should emphasize the importance of understanding cultural diversity and universality. In addition, it is necessary to strengthen or equip hospitals with the necessary medical equipment and supplies to meet the expectations of people. The researchers surmise that implementing all of these suggestions could help reduce the harm caused by treatable diseases.

References

- Berg, A.; Patel, S.; Aukrust, P.; David, C.; Gonca, M.; Berg, E.S.; Dalen, I.; Langeland, N. Increased severity and mortality in adults co-infected with malaria and HIV in Maputo, Mozambique: A prospective cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e88257.

- Whetten, K.; Leserman, J.; Whetten, R.; Ostermann, J.; Thielman, N.; Swartz, M.; Stangl, D. Exploring lack of trust in care providers and the government as a barrier to health service use. Am. J. Public Health 2006, 96, 716–721.

- Cassy, A.; Saifodine, A.; Candrinho, B.; do Rosário Martins, M.; da Cunha, S.; Pereira, F.M.; Gudo, E.S. Care-seeking behaviour and treatment practices for malaria in children under 5 years in Mozambique: A secondary analysis of 2011 DHS and 2015 IMASIDA datasets. Malar. J. 2019, 18, 1–10.

- Alemu, T.; Biadgilign, S.; Deribe, K.; Escudero, H.R. Experience of stigma and discrimination and the implications for healthcare seeking behavior among people living with HIV/AIDS in resource-limited setting. SAHARA-J J. Soc. Asp. HIV AIDS 2013, 10, 1–7.

- Munguambe, K.; Boene, H.; Vidler, M.; Bique, C.; Sawchuck, D.; Firoz, T.; Makanga, P.T.; Qureshi, R.; Macete, E.; Menéndez, C. Barriers and facilitators to health care seeking behaviours in pregnancy in rural communities of southern Mozambique. Reprod. Health 2016, 13, 83–97.

- Posse, M.; Meheus, F.; Van Asten, H.; Van Der Ven, A.; Baltussen, R. Barriers to access to antiretroviral treatment in developing countries: A review. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2008, 13, 904–913.

- Ostherr, K.; Killoran, P.; Shegog, R.; Bruera, E. Death in the digital age: A systematic review of information and communication technologies in end-of-life care. J. Palliat. Med. 2016, 19, 408–420.

- Anselmi, L.; Lagarde, M.; Hanson, K. Health service availability and health seeking behaviour in resource poor settings: Evidence from Mozambique. Health Econ. Rev. 2015, 5, 1–13.

- Honwana, A.M. Healing for peace: Traditional healers and post-war reconstruction in Southern Mozambique. Peace Confl. 1997, 3, 293–305.

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Report on Traditional and Complementary Medicine 2019; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Ferrão, L.J.; Fernandes, T.H. Community oriented interprofessional health education in Mozambique: One student/one family program. Educ. Health 2014, 27, 103.

- Atwine, F.; Hultsjö, S.; Albin, B.; Hjelm, K. Health-care seeking behaviour and the use of traditional medicine among persons with type 2 diabetes in south-western Uganda: A study of focus group interviews. Pan. Afr. Med. J. 2015, 20, 76.

- Napier, A.D.; Ancarno, C.; Butler, B.; Calabrese, J.; Chater, A.; Chatterjee, H.; Guesnet, F.; Horne, R.; Jacyna, S.; Jadhav, S. Culture and health. Lancet 2014, 384, 1607–1639.

- Winiger, F.; Peng-Keller, S. Religion and the World Health Organization: An evolving relationship. BMJ Glob. Health 2021, 6, e004073.

- Abubakar, A.; Van Baar, A.; Fischer, R.; Bomu, G.; Gona, J.K.; Newton, C.R. Socio-cultural determinants of health-seeking behaviour on the Kenyan coast: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71998.

- Ibanez-Gonzalez, D.L.; Mendenhall, E.; Norris, S.A. A mixed methods exploration of patterns of healthcare utilization of urban women with non-communicable disease in South Africa. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 1–9.

- Audet, C.M.; Sidat, M.; Blevins, M.; Moon, T.D.; Vergara, A.; Vermund, S.H. HIV knowledge and health-seeking behavior in Zambe zia Province, Mozambique. SAHARA-J J. Soc. Asp. HIV AIDS 2012, 9, 41–46.

- Bonate, L. Islam in northern Mozambique: A historical overview. Hist. Compass 2010, 8, 573–593.

- Burchett, W.G. Southern Africa Stands Up: The Revolutions in Angola, Mozambique, Rhodesia, Namibia, and South Africa; Urizen Books: New York, NY, USA, 1978.

- Gumende, A. Mozambique: Historical Trajectories and Development. Hisp. Res. J. 2010, 11, 172–185.

- WorldAtlas. Ethnic Groups of Mozambique. 2022. Available online: https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/ethnic-groups-of-mozambique.html#:~:text=The%20main%20ethnic%20groups%20in,of%20the%20population%2C%20as%20well (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- The World Factbook. Mozambique. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/mozambique/#people-and-society (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Creasey, A. Willingness-to-Pay for Halal and Branded Poultry in Northern Mozambique. Agricultural Education, Communications and Technology Undergraduate Honors Theses. 2021. Available online: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/aectuht/13 (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Mozambique. International Religious Freedom Report. 2019. Available online: https://mz.usembassy.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/182/MOZAMBIQUE-2019-INTERNATIONAL-RELIGIOUS-FREEDOM-REPORT.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Wikipedia. Economy of Mozambique. 2022. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economy_of_Mozambique (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Minter, W. Apartheid’s Contras: An Inquiry into the Roots of War in Angola and Mozambique; Zed Books: London, UK, 1994.

- Leininger, M.M.; McFarland, M.R. Culture Care Diversity and Universality: A Worldwide Nursing Theory; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Burlington, MA, USA, 2006.

- Chukwuneke, F.; Ezeonu, C.; Onyire, B.; Ezeonu, P. Culture and biomedical care in Africa: The influence of culture on biomedical care in a traditional African society, Nigeria, West Africa. Niger. J. Med. 2012, 21, 331–333.

- McElroy, A. Medical Anthropology in Ecological Perspective; Routledge, Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2018.

- Audet, C.M.; Ngobeni, S.; Wagner, R.G. Traditional healer treatment of HIV persists in the era of ART: A mixed methods study from rural South Africa. BMC Complementary Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 1–6.

- Sabuni, L.P. Dilemma with the local perception of causes of illnesses in central Africa: Muted concept but prevalent in everyday life. Qual. Health Res. 2007, 17, 1280–1291.

- Fearon, J.D. Ethnic and cultural diversity by country. J. Econ. Growth 2003, 8, 195–222.

- Makundi, E.A.; Malebo, H.M.; Mhame, P.; Kitua, A.Y.; Warsame, M. Role of traditional healers in the management of severe malaria among children below five years of age: The case of Kilosa and Handeni Districts, Tanzania. Malar. J. 2006, 5, 1–9.

- Abdullahi, A.A. Trends and challenges of traditional medicine in Africa. Afr. J. Tradit. Complementary Altern. Med. 2011, 8, 115–123.

More

Information

Subjects:

Health Care Sciences & Services

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.3K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

14 Mar 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No