Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Peijun Zhang | + 1196 word(s) | 1196 | 2022-03-10 04:06:23 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 1196 | 2022-03-11 03:43:23 | | | | |

| 3 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 1196 | 2022-03-14 05:21:07 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Zhang, P. Gut Microbial Characterization of Melon-Headed Whales. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20442 (accessed on 16 January 2026).

Zhang P. Gut Microbial Characterization of Melon-Headed Whales. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20442. Accessed January 16, 2026.

Zhang, Peijun. "Gut Microbial Characterization of Melon-Headed Whales" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20442 (accessed January 16, 2026).

Zhang, P. (2022, March 10). Gut Microbial Characterization of Melon-Headed Whales. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20442

Zhang, Peijun. "Gut Microbial Characterization of Melon-Headed Whales." Encyclopedia. Web. 10 March, 2022.

Copy Citation

Although gut microbes are regarded as a significant component of many mammals and play a very important role, there is a paucity of knowledge around marine mammal gut microbes, which may be due to sampling difficulties. Moreover, to date, there are very few, if any, reports on the gut microbes of melon-headed whales.

melon-headed whale

gut

microbial communities

1. Introduction

The melon-headed whale (Peponocephala electra) is a member of the subfamily Globicephalinae, where it is most closely related to the larger pilot whales (Globicephala melas and G. macrorhynchus), and it is also not a well-known species [1]. This whale is mostly dark gray in color, with a faint dark gray cloak on its back and a narrow head that slopes downward below a tall sickle-shaped dorsal fin. This species is difficult to distinguish at sea from the pygmy killer whale (Feresa attenuata). However, in stranded specimens, the melon-headed whale can be identified from all other pygmy killer whales by its high tooth count, as the melon-headed whale has ~25 teeth per row, while the pygmy killer whale has only about ~15 teeth per row [2]. Melon-headed whales are found worldwide in tropical and warm–temperate waters [3]. They mainly feed on fish, squid, cuttlefish, and shrimp, foraging from the littoral zone down to the bathypelagic zone [2][4][5].

Microbes are exceedingly abundant and varied in the gut of mammals [6]. Interactions between microbes and their host are necessary for the regulation of health, survival, and physiological functions of the host [7][8][9]. The majority of microbes reside in the gut, and their associated phenotypes shape the immune system of the host and contribute to nutrient uptake and defense against infectious diseases [10][11]. Therefore, revealing the mammalian gut microbiota is essential to fully understand the physiology and health status of mammals themselves. To date, most studies have focused on human gut microbiota, and information on the gut microbial composition of other mammals, especially cetaceans, although there are some reports, remains relatively scarce due to sampling limitations.

According to previous reports, gut samples from cetaceans are mainly obtained from three approaches: (1) feces in the wild just post-defecation. For example, Sanders et al. [12] investigated the microbial diversity and function of gut microbiomes in baleen whales feces and found them harbored unique gut microbiomes whereas still kept a functional capacity similar to that of both carnivores and herbivores; (2) fecal samples from human cared animals, such as studies on belugas (Delphinapterus leucas), Pacific white-sided dolphins (Lagenorhynchus obliquidens) and common bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) [13][14], and Yangtze finless porpoises (Neophocaena phocaenoides asiaeorientalis) [15]; and (3) from dead, stranded animals. A few of studies sequenced along the gastrointestinal tracts of stranded cetaceans to investigate the distribution of microorganisms in different gut regions [16][17][18][19].

2. Sequencing Statistics and Microbial Diversity

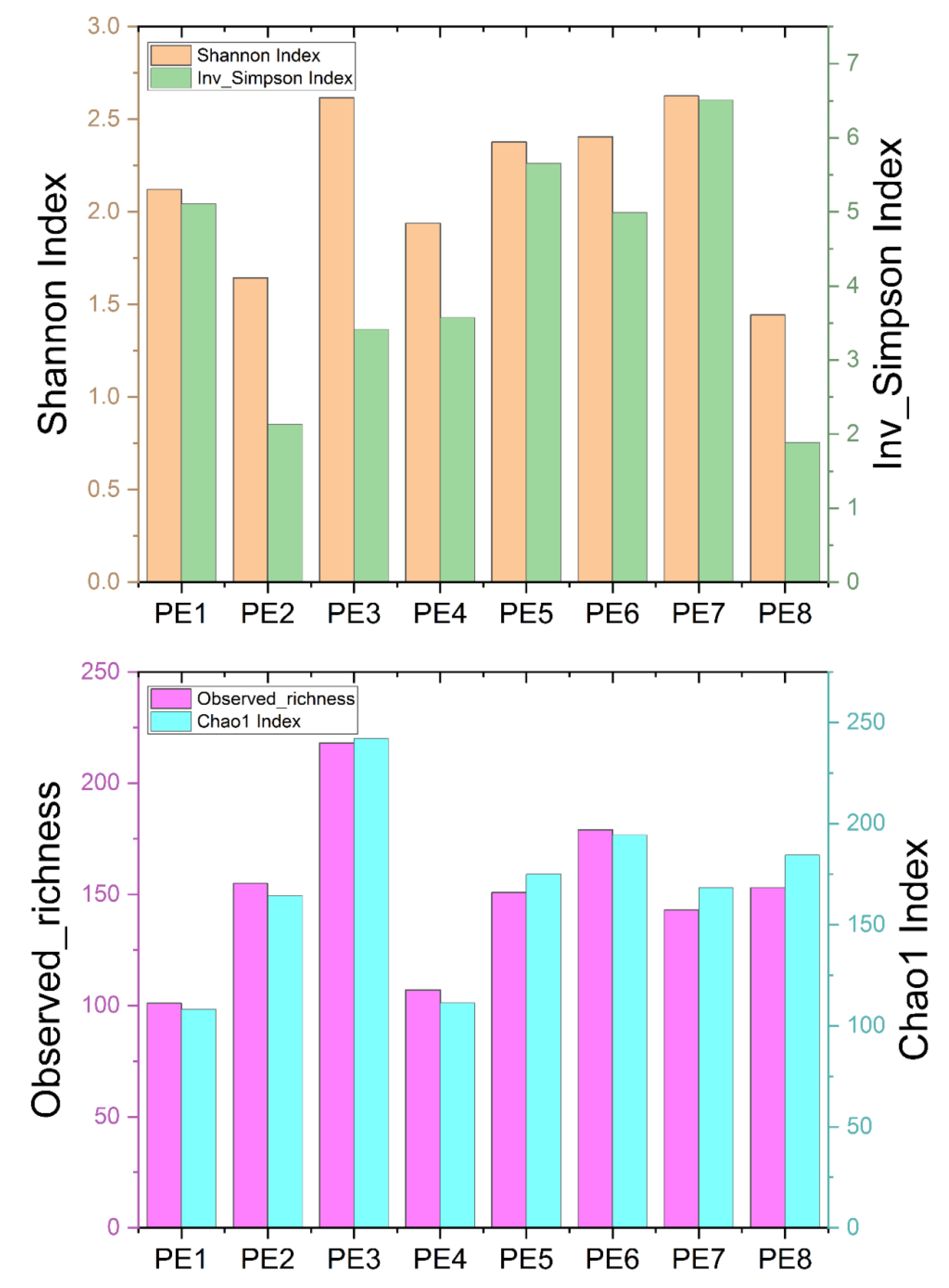

Originally, a total of 642,263 sequences were obtained from 8 fecal samples of 8 stranded melon-headed whales (assigned as PE1 to PE8) after quality assessment. To obtain more accurate α-diversity results to analyze microbial diversity, composition, and structure, researchers rarefied the sequences of each sample to 34,224. The α-diversities of microbial communities from the gut of eight melon-headed whales were calculated. The results showed PE8 and PE2 had lower Shannon and Inverse Simpson indices, while PE1 and PE4 had lower Chao1 indices and observed richness (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Four α-diversity indices—Shannon index, Inverse Simpson index, observed richness, and Chao1 index—of the eight fecal specimens from eight stranded melon-headed whales (PE1-8). The results are based on the ASV datasets.

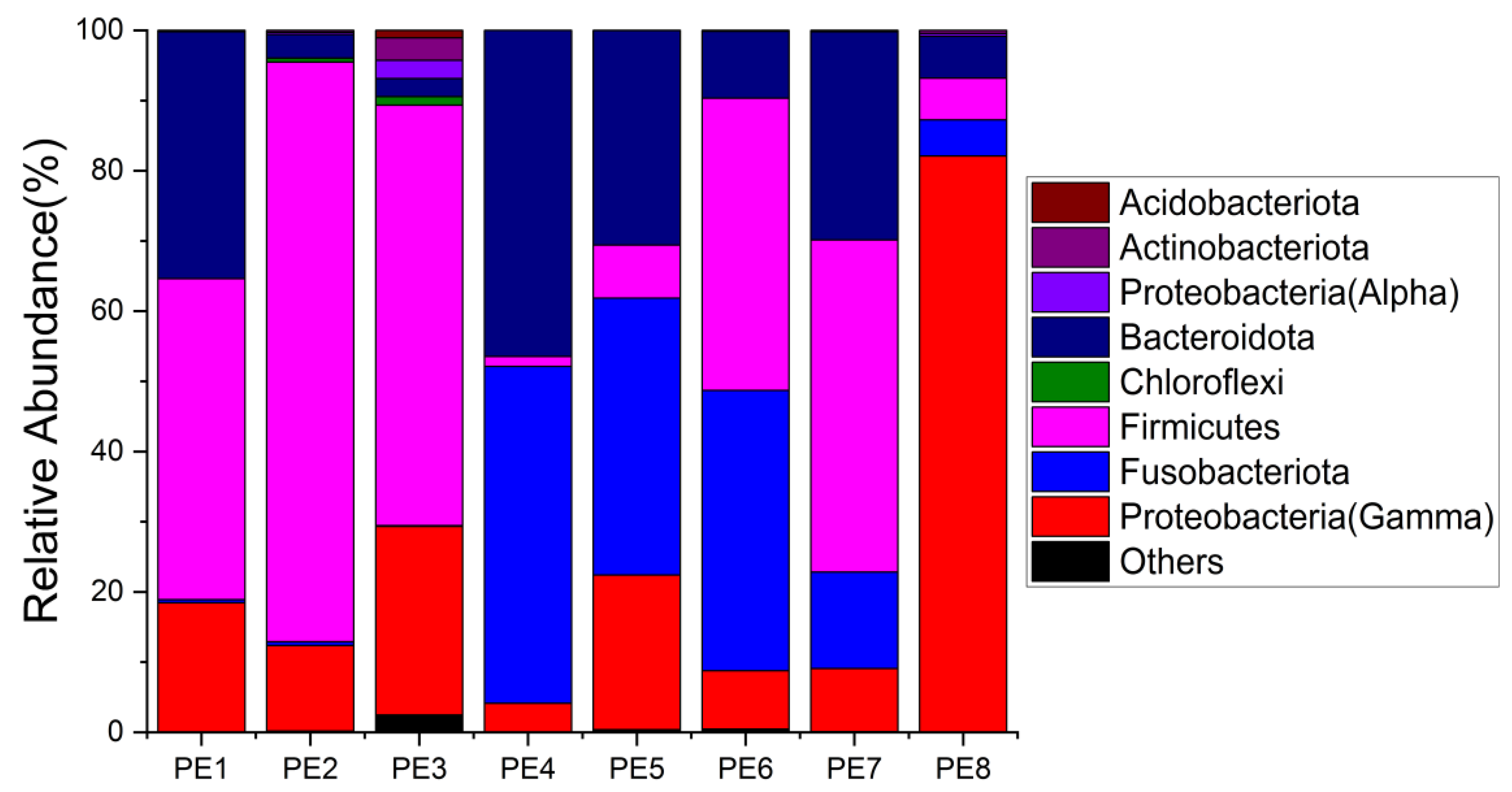

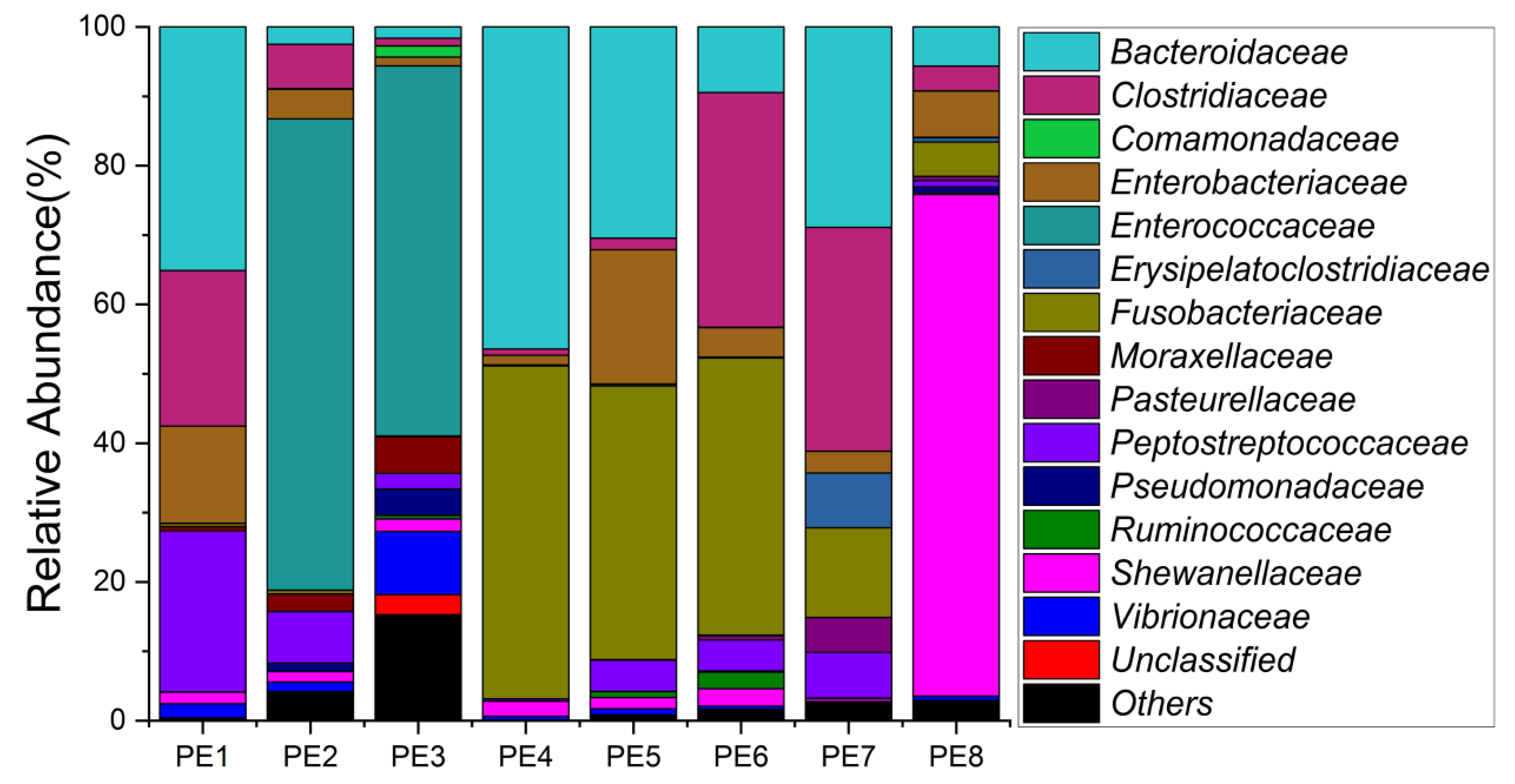

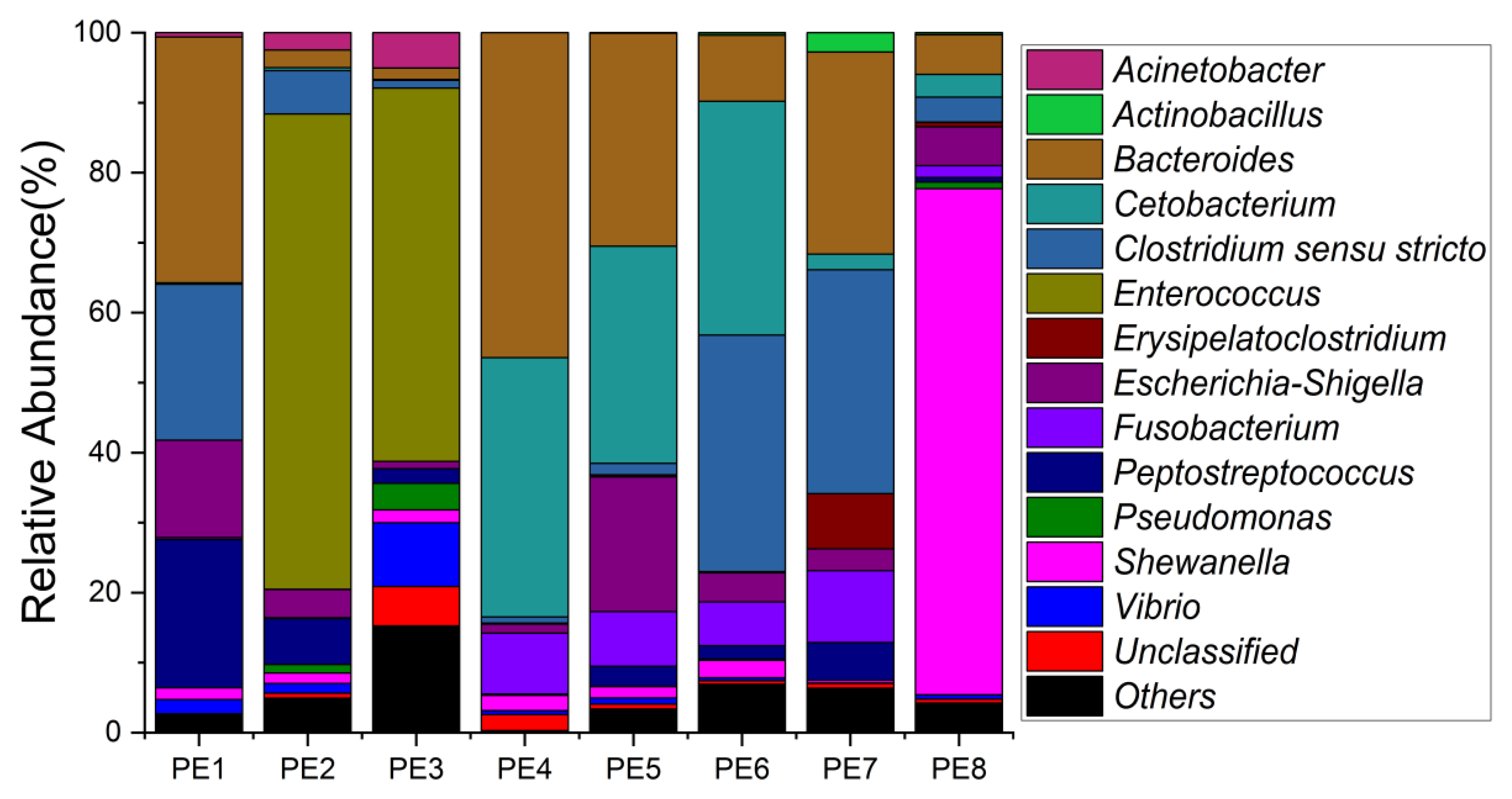

The relative abundance of gut microbes was apparent at the phylum, family, and genus levels, with a similarity of 97% for ASV taxonomy, and provided detailed relative abundance information on gut microbial community composition (Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4). Furthermore, researchers also provided the datasets of ASV table and the information of classification. Firmicutes, Fusobacteriota, and Bacteroidota were the dominant bacterial lineages in the fecal samples of melon-headed whales, while the majority of the fecal samples from the PE8 in this study were dominated by Proteobacteria (Gamma), accounting for 82%. At the family taxonomic level, Fusobacteriaceae, Enterococcaceae, and Bacteroidaceae, which are affiliated with Fusobacteriales, Lactobacillales, and Bacteroidales, respectively, were the dominant bacterial lineages in the fecal samples of PE1 to PE7. However, the respective compositions of different fecal samples were slightly different; for instance, the fecal sample of PE8 was dominated by Shewanellaceae (Enterobacterales, 72%). Furthermore, at the genus taxonomic level, the gut microbial communities of melon-headed whales were mainly composed of Cetobacterium, Bacteroides, Clostridium sensu stricto, and Enterococcus. Nevertheless, the distribution of these dominant bacterial lineages in different fecal samples is different. For instance, Cetobacterium was dominant in the fecal samples of PE4, PE5, and PE6; Bacteroides was dominant in the samples of PE1, PE4, and PE7; and Clostridium sensu stricto was dominant in the samples of PE1, PE6, and PE7. The fecal samples of PE2 and PE3 were dominated by Enterococcus, which accounted for 68% and 53%, respectively. Only one ASV was annotated with Shewanella, and this ASV was annotated at the level of species as Shewanella algae. This bacterium was distributed in all fecal samples, but in the sample of PE8, Shewanella algae was the overwhelmingly dominant bacterium, accounting for 72% (Figure 4).

Figure 2. Gut microbial community members of eight stranded melon-headed whales (PE1-8) at the phylum level.

Figure 3. Gut microbial community members of eight stranded melon-headed whales (PE1-8) at the family level.

Figure 4. Gut microbial community members of eight stranded melon-headed whales (PE1-8) at the genus level.

3. Co-Occurrence Network and Functional Profile of Gut Microbial Communities

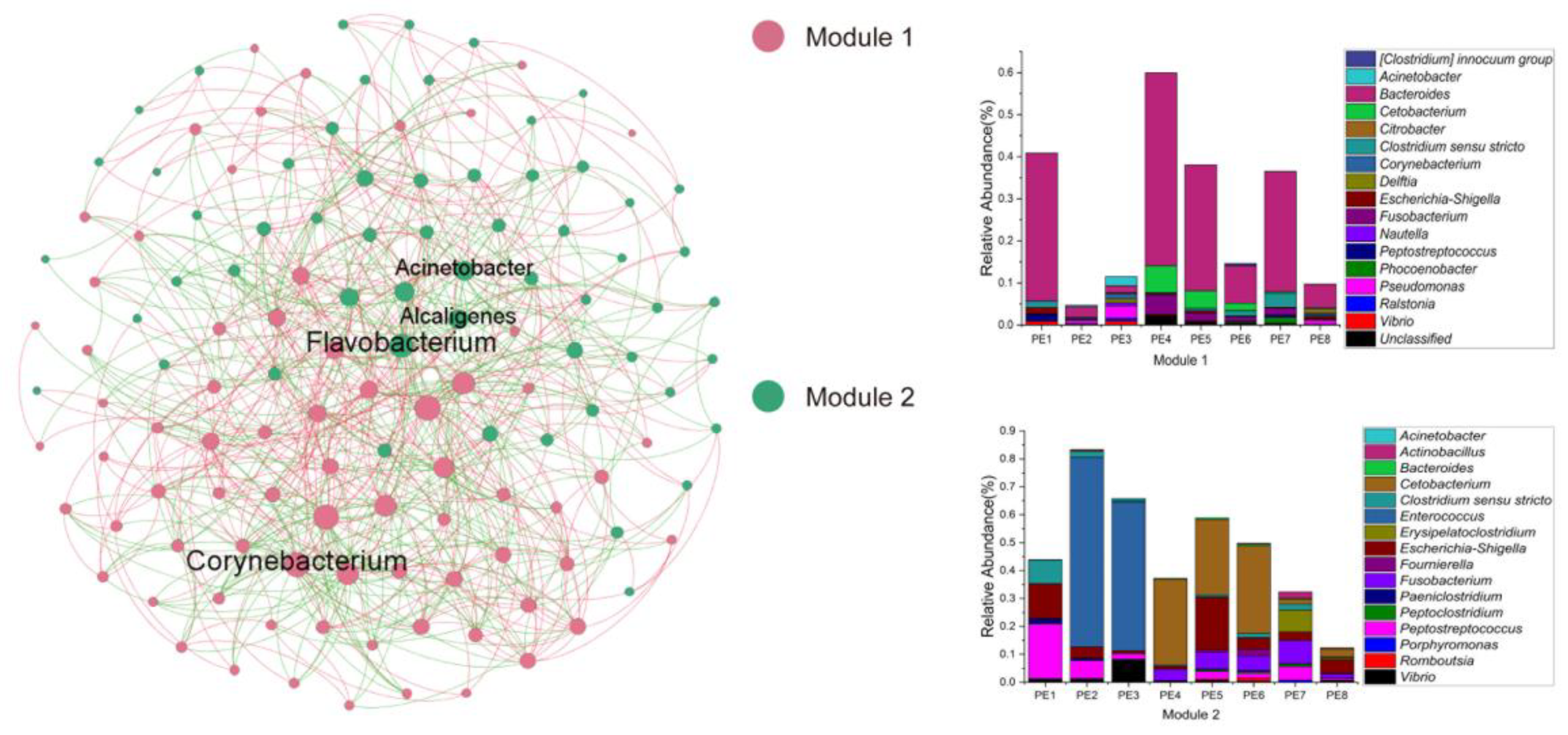

In order to reveal the gut microbial community interactions of melon-headed whales, the network was constructed through the MENA approach. The nodes and links of this network were 128 and 676, respectively. The average clustering coefficient (avgCC) was 0.337, and the average path distance (GD) was 2.513. This network formed a total of two modules (a set of nodes that have strong interactions): module one was mainly composed of Bacteroides, while module two was mainly composed of Cetobacterium and Enterococcus. Moreover, the keystone taxa belonged to module hubs, composed of those ASVs with Zi > 2.5, Pi ≤ 0.62, in the microbial network of melon-headed whales; the keystone genera were Acinetobacter, Alcaligenes, Corynebacterium, and Flavobacterium (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Co-occurrence networks of gut microbial communities. Stacked bar chart shows relative abundance of ASVs in Modules 1 and 2; a Module is a set of nodes that have strong interactions; these samples were collected from eight stranded melon-headed whales (PE1-8).

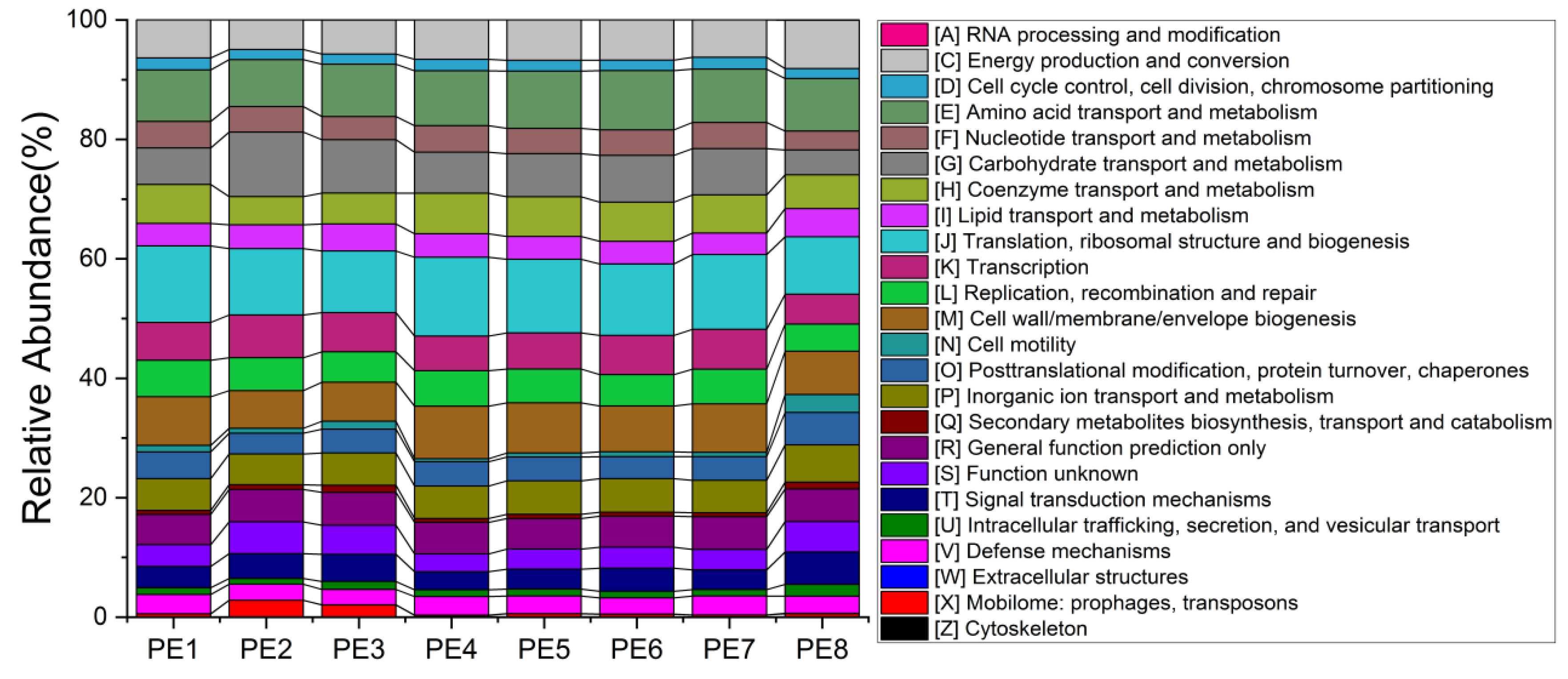

To better understand the potential functions of melon-headed whale gut bacteria, researchers explored the functional features of microbial communities using the newly updated PICRUSt2 software. No obvious functional difference was found between individuals. The main functions involved in the gut microbes of stranded melon-headed whales include the following: RNA processing and modification; energy production and conversion; cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning; amino acid transport and metabolism; nucleotide transport and metabolism; carbohydrate transport and metabolism; coenzyme transport and metabolism; lipid transport and metabolism; translation, ribosomal structure, and biogenesis; transcription; replication, recombination, and repair; cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis; cell motility; post-translational modification, protein turnover, chaperones; inorganic ion transport and metabolism; secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport, and catabolism; signal transduction mechanisms; intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport, and defense mechanisms (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Functional profiles of gut microbial communities predicted by PICRUSt2; these samples were collected from eight stranded melon-headed whales (PE1-8).

References

- Vilstrup, J.T.; Ho, S.Y.; Foote, A.D.; A Morin, P.; Kreb, D.; Krützen, M.; Parra, G.J.; Robertson, K.M.; De Stephanis, R.; Verborgh, P.; et al. Mitogenomic phylogenetic analyses of the Delphinidae with an emphasis on the Globicephalinae. BMC Evol. Biol. 2011, 11, 65.

- Perryman, W.L.; Danil, K. Melon-Headed Whale. In Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, 3rd ed.; Wursig, B., Thewissen, J.G.M., Kovacs, K., Eds.; Academy Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 593–595.

- Jefferson, T.A.; Webber, M.A.; Pitman, R. Marine Mammals of the World: A Comprehensive Guide to their Identification, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, 2015.

- Jefferson, T.A.; Barros, N.B. Peponocephala electra. Mammalian Species 1997, 553, 1–6.

- Spitz, J.; Cherel, Y.; Bertin, S.; Kiszka, J.; Dewez, A.; Ridoux, V. Prey preferences among the community of deep-diving odontocetes from the Bay of Biscay, Northeast Atlantic. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2011, 58, 273–282.

- Gensollen, T.; Iyer, S.S.; Kasper, D.L.; Blumberg, R.S. How colonization by microbiota in early life shapes the immune system. Science 2016, 352, 539–544.

- Dang, A.T.; Marsland, B.J. Microbes, metabolites, and the gut–lung axis. Mucosal Immunol. 2019, 12, 843–850.

- Krajmalnik-Brown, R.; Ilhan, Z.-E.; Kang, D.-W.; DiBaise, J.K. Effects of Gut Microbes on Nutrient Absorption and Energy Regulation. Nutr. Clin. Pr. 2012, 27, 201–214.

- Woting, A.; Blaut, M. The Intestinal Microbiota in Metabolic Disease. Nutrients 2016, 8, 202.

- Dzutsev, A.; Badger, J.H.; Perez-Chanona, E.; Roy, S.; Salcedo, R.; Smith, C.K.; Trinchieri, G. Microbes and Cancer. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 35, 199–228.

- Quin, C.; Gibson, D.L. Human behavior, not race or geography, is the strongest predictor of microbial succession in the gut bacteriome of infants. Gut Microbes 2020, 11, 1143–1171.

- Sanders, J.G.; Beichman, A.C.; Roman, J.; Scott, J.; Emerson, D.; McCarthy, J.J.; Girguis, P.R. Baleen whales host a unique gut microbiome with similarities to both carnivores and herbivores. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8285.

- Bai, S.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, C.; Du, J.; Du, X.; Zhu, C.; Liu, J.; Xie, P.; Li, S. Comparative Study of the Gut Microbiota Among Four Different Marine Mammals in an Aquarium. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12.

- Suzuki, A.; Segawa, T.; Sawa, S.; Nishitani, C.; Ueda, K.; Itou, T.; Asahina, K.; Suzuki, M. Comparison of the gut microbiota of captive common bottlenose dolphins Tursiops truncatus in three aquaria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 126, 31–39.

- McLaughlin, R.W.; Chen, M.; Zheng, J.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, D. Analysis of the bacterial diversity in the fecal material of the endangered Yangtze finless porpoise, Neophocaena phocaenoides asiaeorientalis. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2011, 39, 5669–5676.

- Bai, S.; Zhang, P.; Lin, M.; Lin, W.; Yang, Z.; Li, S. Microbial diversity and structure in the gastrointestinal tracts of two stranded short-finned pilot whales (Globicephala macrorhynchus) and a pygmy sperm whale (Kogia breviceps). Integr. Zool. 2021, 16, 324–335.

- Tian, J.; Du, J.; Lu, Z.; Han, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, D.; Guan, X.; Wang, Z. Distribution of microbiota across different intestinal tract segments of a stranded dwarf minke whale, Balaenoptera acutorostrata. MicrobiologyOpen 2020, 9.

- Wan, X.; Li, J.; Cheng, Z.; Ao, M.; Tian, R.; Mclaughlin, R.W.; Zheng, J.; Wang, D. The intestinal microbiome of an Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin (Sousa chinensis) stranded near the Pearl River Estuary, China. Integr. Zool. 2021, 16, 287–299.

- Wan, X.-L.; McLaughlin, R.W.; Zheng, J.-S.; Hao, Y.-J.; Fan, F.; Tian, R.-M.; Wang, D. Microbial communities in different regions of the gastrointestinal tract in East Asian finless porpoises (Neophocaena asiaeorientalis sunameri). Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–10.

More

Information

Subjects:

Microbiology

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

750

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

14 Mar 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No