Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wen Qian | + 2309 word(s) | 2309 | 2022-03-08 09:52:00 | | | |

| 2 | Beatrix Zheng | + 4 word(s) | 2313 | 2022-03-11 02:16:49 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Qian, W. Classic Forcefield Refitted for Energetic Materials. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20438 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Qian W. Classic Forcefield Refitted for Energetic Materials. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20438. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Qian, Wen. "Classic Forcefield Refitted for Energetic Materials" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20438 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Qian, W. (2022, March 10). Classic Forcefield Refitted for Energetic Materials. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20438

Qian, Wen. "Classic Forcefield Refitted for Energetic Materials." Encyclopedia. Web. 10 March, 2022.

Copy Citation

Energetic materials (EM) act as the key chemical activity component in weapon systems, and energetic crystals are the main and functional part therein. Until now, the most widely used energetic crystals have been molecular crystals, including TNT, RDX, HMX, and TATB. The thermal properties, mechanical properties, and chemical reactivity of energetic molecular crystals are of great importance for a whole EM. The classic forcefields (FF) are still useful for typical energetic crystals—i.e., even though they generally have simple potential functions, the accuracy can be ensured by refitting for specific compound.

molecular forcefield

energetic materials

molecular dynamics simulation

1. Development of Refitted FFs

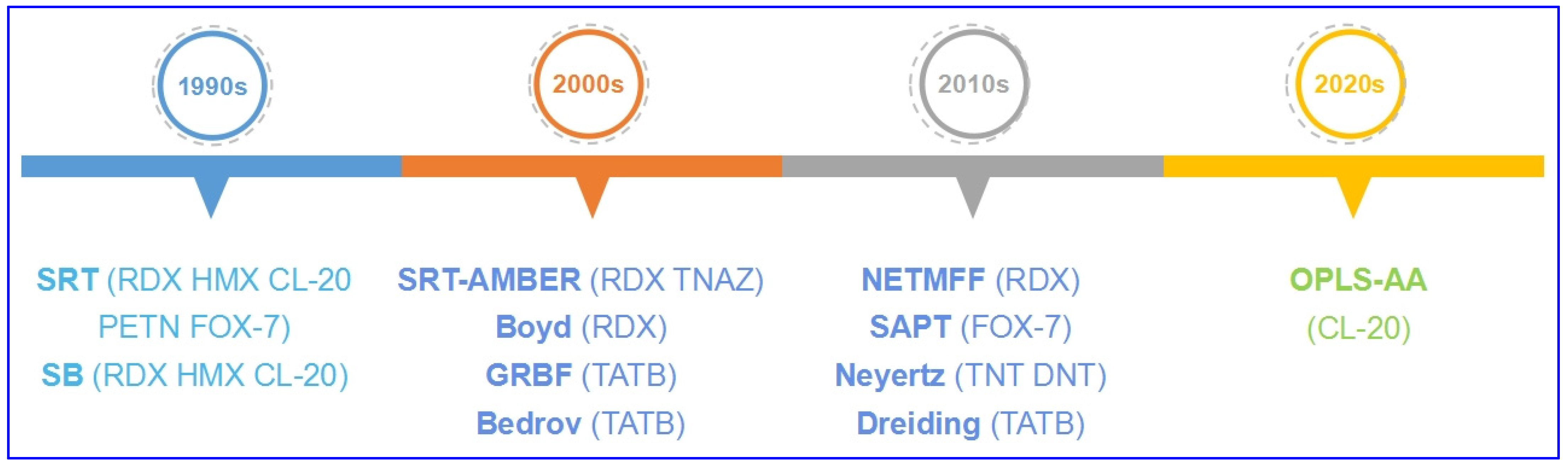

In order to investigate the precise structure and properties of energetic molecular crystals, classic molecular classic forcefields (FF) were refitted for Energetic materials (EMs) (Figure 1 and Table 1). In the 1990s, Sorescu et al. [1][2][3][4][5][6] developed a classic FF (SRT) with pair potential refitted for predicting lattice parameters, density, bulk modulus, and shear modulus of aliphatic energetic compounds—including nitramine heterocycles RDX, HMX, and CL-20, and linear conjugated energetic compound FOX-7. It was also applied on linear nitrate PETN which has overloaded substituents with lower accuracy [7]. Smith et al. [8] developed another kind of multi-particle potential, the Smith–Bharadwaj (SB) potential, which is widely used in the calculations of shock compression, shear bands, elastic constants, and modulus for HMX, CL-20, and RDX [9][10][11][12].

Figure 1. Development of classic FFs refitted for EMs.

In the 2000s, more classic FFs were applied. For RDX crystal, Agrawal et al. [13][14] combined the advantages of traditional AMBER FF with SRT FF, and applied the refitted FF (SRT-AMBER) which can effectively describe the flexibility of molecules on the calculations of cell parameters, melting point, and mechanics for TNAZ and RDX. Boyd et al. [15] also developed a multi-particle potential for RDX; thereby, the vibration spectra, thermodynamics, thermal expansion, and mechanics were calculated. For aromatic nitro compound TATB, a multi-particle FF (GRBF) with Lennard–Jones portion is developed by Gee et al. [16] using an ab initio approach for large molecular system TATB crystal, with cell parameters, density, thermal expansion, and pressure–volume isotherm prediction. Bedrov et al. [17] developed a potential to calculate the vibration spectra, elastic stiffness coefficients, and isotropic moduli; moreover, thermal conductivity can also be obtained using non-equilibrium molecular dynamics (NEMD) under Bedrov’s potential [18].

In the 2010s, the symmetry-adapted perturbation theory (SAPT)-based potential was also applied to describe thermal properties for FOX-7 [19], and thermal expansion and pressure response were investigated thereby. Neyertz et al. [20] developed a classic potential for aromatic nitro compounds TNT and DNT, which possess conjugated structure, and calculated the cell parameters, density, tensile modulus, bulk modulus, and shear modulus. Song et al. [21] developed an all-atom, non-empirical, tailor-made FF (NETMFF) for RDX, and cell parameters, density, and thermal expansion were predicted thereby; the Dreiding FF was also applied on TATB, with the anisotropic thermal expansion simulated successfully [22][23].

Table 1. Energy expressions and application scopes for the classic FFs.

| FFs | Valence Terms | van der Waals Interaction Term |

Electrostatic Interaction Term | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRT [1] | \ | Buckingham 6-exp form | Coulomb function | RDX HMX CL-20 FOX-7 PETN (lattice parameter, density, mechanics) |

| SAPT [19] | \ | Buckingham 6-exp form | Simplified Coulomb function | FOX-7 (thermal properties, pressure responses, isothermo) |

| SRT-AMBER [13] | Harmonic bond stretching, harmonic angle bending, cosine torsion term | Buckingham 6-exp form | Coulomb function | RDX (lattice parameter, density, melting point, mechanics) TNAZ (lattice parameter, density, melting point) |

| SB [8] | Harmonic bond term, angle term, dihedral term, anharmonic torsion term | Buckingham form | Coulomb function | RDX HMX CL-20 (shock compression, shear bands, elastic constants and modulus) |

| Boyd’s [15] | Bond stretching described by Morse function, angle bending described by harmonic function | Buckingham LJ 6-12 form | Coulomb function | RDX (lattice parameter, density, thermodynamics, vibration spectra, thermal expansion, mechanics) |

| NETMFF [21] | Bond term, angle term, dihedral (torsion angle) term, out-of-plane bending angle term, cross-coupling terms of bond–bond, bond–angle couplings | Damped Buckingham form | Coulomb function | RDX (lattice parameter, density, thermal expansion) |

| GRBF [16] | Harmonic bond stretch term, bond-angle bend term, dihedral angle torsion term | Lennard–Jones 12-6 form | Coulomb function | TATB (lattice parameters, density, thermal expansion, isotherm) |

| Bedrov’s [17] | Harmonic functions of covalent bonds, three-center bends, and improper dihedrals | Buckingham 6-exp form | Coulomb function | TATB (lattice parameter, thermal expansion, mechanics, vibration spectra, thermal conductivity) |

| Neyertz’s [20] | Angle-bending deformations described by harmonic function, torsional motions around the dihedral angles τ, sp2 ring and NO2 structures kept planar described by harmonic function | Lenard-Jones 12-6 form | Coulomb function | TNT DNT (lattice parameter, density, tensile, bulk and shear modulus) |

| Dreiding [22] | Bond stretching interaction term, angle bending interaction term, dihedral angle interaction term, inversion interaction term | Lennard–Jones 12-6 form | Coulomb function | TATB (geometries, crystal packing, thermal expansion) |

| OPLS-AA [24] | Bond term, angle term, dihedral term | Lennard–Jones 12-6 form | Coulomb function | CL-20 (lattice parameter, density, polymorph prediction) |

In 2021, Wang et al. developed a tailor-made OPLS all-atom FF (OPLS-AA) [24] with polymorphism of CL-20 being predicted successfully [25].

2. Functional Forms of the Refitted FFs

The energy expressions of the classic FFs have something in common, i.e., most of FFs have valence terms, van der Waals interaction terms, and electrostatic interaction terms, and they differ only in functional forms (Table 1). For aliphatic energetic compounds including heterocycles RDX, HMX, CL-20, and linear PETN, FOX-7, SRT potential was applied. The energy expression of SRT only has a pairwise Buckingham 6-exp form with repulsion and dispersion interactions, and a Coulombic potential of electrostatic interactions [1]. The energy expression of SAPT potential is similar to the SRT pair potential, and it was also applied on FOX-7 [19].

For the multi-particle potentials of nitramine heterocycles, the energy terms of SB potential cover harmonic bonds, angles, dihedrals terms, anharmonic torsions, and non-bonded Buckingham and Coulomb interactions [8]. SRT-AMBER combines the forms of SRT and AMBER FFs, with harmonic bond stretching and angle bending terms, cosine torsion term, and nonbond term replaced by Buckingham (exp-6) potential and Coulombic potential in SRT [13]. Boyd’s multi-particle potential contains bond stretching, angle bending, vdW term, and electrostatic term; described by Morse function, harmonic function, Buckingham potential LJ 6-12, and Coulomb function, respectively [15]. In comparison, NETMFF is more complex, with more valence terms included, as listed in Table 1 [21].

For the aromatic nitro compounds, GRBF and Bedrov’s potential were applied for TATB, and Neyertz’s FF was applied for TNT and DNT. GRBF FF includes valence terms containing harmonic bond stretch, bond-angle bend, dihedral angle torsion, and intermolecular pair potentials, including a Coulombic electrostatic term Eel and a Lennard–Jones LJ 12-6 term [16]. Bedrov’s potential includes the harmonic functions of covalent bonds, three-center bends and improper dihedrals, and nonbonded interactions of Buckingham (exp-6) potential and Coulomb interactions [17]. In Neyertz’s potential, angle-bending deformations are described by harmonic function, and torsional motions around the dihedral angles τ are represented by a polynomial in cos τ, while sp2 ring and NO2 structures maintain planarity by using harmonic function [20]. Moreover, some general FFs were also refitted for energetic crystals, such as Dreiding for TATB [22] and OPLS-AA for CL-20 [24].

To date, the effects of different molecular structures—especially functional groups—were considered to make precise predictions. Initially, SRT [1] and SAPT FFs [19] are simple pair potentials which only describe the intermolecular interactions, with assumption of rigid molecules, thus they cannot describe the effect of different molecular structures, resulting in lower accuracy. Combing the rigid-molecule SRT potential with intramolecular interactions from AMBER, the SRT-AMBER potential [13] accurately predicted the chair and inverted chair conformation, bond lengths, and bond angles of the RDX molecule; however, the parameters for the N-NO2 improper dihedral angles are not available in AMBER, and the parameters for O-NO2 were used in SRT-AMBER, and there are some inaccuracies in the calculated orientations of the NO2 groups; thus, modifications in the torsional parameters are needed. SB potential [8] with anharmonic torsions terms that display extrema at the torsion angles that correspond to stationary points on the conformational energy surface can effectively predict lattice parameters and elastic tensors for RDX and HMX. Furthermore, Boyd’s potential [15] managed to stabilize the RDX crystal lattice with flexible molecules in the correct conformation, with Morse bond stretching, harmonic angle bending, cosine torsions terms, and in which the torsion parameter C-N-N-O values were modified to adjust the N-NO2 rotational barrier. Moreover, in NETMFF for RDX [21], many more parameters regarding functional groups were considered, including parameters c_4 for the carbon atom, n_3r for the nitrogen atom of the triazine ring, n_3o for the nitrogen atom of the NO2 group, o_1 for the oxygen atom, and h_1 for the hydrogen atom; as well as torsion parameters for six RDX conformers. Consequently, the angles and torsions for the NO2 group are well described, and the lattice parameters and thermal expansion are well predicted. In GRBF for TATB [16], the amino C-C-N-H and nitro C-C-N-O group rotational barriers were modified, and the nonbonded interactions for amino groups and nitro groups were also considered; similar parameters were considered in Neyertz’s potential for TNT and DNT [20], as well as in Bedrov’s [17] and Dreiding potentials for TATB [22]. The differences in the functional forms, including descriptions of functional groups for the FFs, bring differences in prediction precision and areas of application.

3. Application of Prediction

3.1. Cell Parameters and Density

The refitted FFs can effectively predict cell parameters, and further density. For example, the cell parameter and density of RDX have been separately predicted using SRT, SRT-AMBER, Boyd’s FF, SB, and NETMFF potentials [1][8][13][15][21]. In comparison, the density prediction by NETMFF is much closer to the experimental results [26], while those by SRT and SRT-AMBER are not so accurate. It is attributed to SRT’s lack of valence terms, while NETMFF has the greatest abundance of valence terms. It shows that the valence terms are important in describing the structural properties of cell parameters and density. Furthermore, the cell parameters and density of TATB can be described well by GRBF, Bedrov’s, and Dreiding FFs [15][16][23]; and those of TNT, DNT, and CL-20 can be described well by Neyertz’s FF [20], and SB [8] and OPLS-AA FFs [25], respectively.

3.2. Polymorphism

Classic FFs have been refitted to predict various crystalline phases and their properties. For example, the Neyertz’s FF [20] was applied to monoclinic and orthorhombic TNT, with density, tensile modulus, bulk modulus, and shear modulus predicted, in agreement with experimental results. Wang et al. [25] also applied the OPLS-AA FF for the polymorph prediction of CL-20, in which the FF parameters were refitted based on DFT calculations with corrected density functional M06-2X, with most polymorphs being reproduced successfully.

3.3. Vibration Spectra

Kroonblawd et al. [18] used the modified Bedrov’s potential to investigate the vibration spectra of TATB. The modified FF overcame the gap between the prediction by the original one and experimental observations. The calculated spectrum can effectively assign the vibration modes, including amine antisymmetric stretch, amine symmetric stretch, amine scissoring plus C-NH2 stretch, nitro antisymmetric stretch plus amine scissor/rock, and ring stretch. The Boyd’s potential [15] has also been effectively applied to investigating the vibration spectra for RDX, in which special attention has been paid to the vibrational states between 200 and 700 cm−1 described as “doorway modes” for the transfer of energy from lattice phonons to the molecular vibrations involved in bond breaking [27][28].

3.4. Thermal Property

Among the thermal properties, thermal expansion is an important feature related to performance. The refitted FFs effectively described the linear and volume thermal expansion for series of energetic crystals: the SRT FF has been refitted for FOX-7, and the linear and volume thermal expansion coefficients (CTE) of FOX-7 crystal were determined from the averages of lattice dimensions extracted from trajectories of MD calculations; the results of linear CTE values show high anisotropy because of the layer wave-like stacking style inside the FOX-7 crystal, in agreement with experiment [7]. The MD simulations for CTE of FOX-7 were also carried out with the fitted SAPT potential, showing a significant anisotropy along different crystalline directions [19]. Compared with experiment [29], SRT is better than SAPT, since SRT and SAPT have the same vdW term, while SAPT has a simplified Coulomb term. It demonstrates the importance of electrostatic interaction in the thermal expansion of FOX-7 crystal. Furthermore, SRT, SRT-AMBER, Boyd’s, and NETMFF FFs were refitted for thermal expansion of RDX crystal. Compared with the experiments [29], it was found that SRT and Boyd’s FFs describe the anisotropy better, while NETMFF tends to isotropy [1][8][15][21]. The GRBF FF [16] was used to predict the CTE for TATB, agreeing well with the experiments [30]. Dreiding FF was also applied to the TATB crystal, with the planar stacking maintained and the anisotropic thermal expansion reproduced successfully [22][23]. Thermal conductivity of TATB was calculated using NEMD with Bedrov’s potential [17]. Therein, the thermal flux, temperature gradient, as well as resulting thermal conductivity, were obtained from direct MD simulations of the slabs, the results from different directions show high anisotropy [18].

3.5. Mechanical Property

The SRT pair potential was refitted for RDX using quantum chemistry calculations at the theoretical level of MP2, and NPT-MD with this refitted potential were performed to predict mechanical properties—including bulk modulus and volume compressibility which match with experiments [1]. The SRT-AMBER potential has also been used to investigate the mechanics for crystalline RDX; however, the prediction accuracy of SRT-AMBER has no advantages compared with other FFs, thus the FF parameters need further modification [13]. Additionally, the SB potential has widely been used to calculate the mechanical properties for energetic crystals of HMX, CL-20, and RDX, with elastic constants and bulk modulus being obtained [8]; the Neyertz’s potential was applied to predict the tensile modulus, bulk modulus, and shear modulus for TNT and DNT [20]; and the elastic stiffness coefficient, bulk modulus, and shear modulus of TATB were accurately predicted using Bedrov’s potential [17][18].

3.6. Shock Responses

For shock responses, the SB potential can effectively describe the shock-induced shear bands in RDX crystal, in which the intermolecular and intramolecular temperatures of a crystalline region and adjacent shear band can be calculated [9]. Moreover, it can describe the shock compression in the RDX crystal, including stress along compression direction, temperature evolution under shock compression, compression ratio, and temperature as a function of shock pressure [10].

References

- Sorescu, D.C.; Rice, B.M.; Thompson, D.L. Intermolecular potential for the hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-s-triazine crystal (RDX): A crystal packing, monte carlo and molecular dynamics study. J. Phys. Chem. B 1997, 101, 798–808.

- Sorescu, D.C.; Rice, B.M.; Thompson, D.L. Molecular packing and NPT-molecular dynamics investigation of the transferability of the RDX intermolecular potential to 2,4,6,8,10,12-hexanitrohexaazaisowurtzitane. J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 948–952.

- Sorescu, D.C.; Rice, B.M.; Thompson, D.L. Isothermal- isobaric molecular dynamics simulations of 1,3,5,7-tetranitro-1,3,5,7-tetraazacyclooctane (HMX) crystals. J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 6692–6695.

- Sorescu, D.C.; Rice, B.M.; Thompson, D.L. A transferable intermolecular potential for nitramine crystals. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 8386–8392.

- Sorescu, D.C.; Rice, B.M.; Thompson, D.L. Molecular packing and molecular dynamics study of the transferability of a generalized nitramine intermolecular potential to non-nitramine crystals. J. Phys. Chem. A 1999, 103, 989–998.

- Sorescu, D.C.; Rice, B.M.; Thompson, D.L. Theoretical studies of the hydrostatic compression of RDX, HMX, HNIW, and PETN crystals. J. Phys. Chem. B 1999, 103, 6783–6790.

- Sorescu, D.C.; Boatz, J.A.; Thompson, D.L. Classical and quantum-mechanical studies of crystalline FOX-7 (1,1-diamino-2,2-dinitroethylene). J. Phys. Chem. A 2001, 105, 5010–5021.

- Smith, G.D.; Bharadwaj, R.K. Quantum chemistry based force field for simulations of HMX. J. Phys. Chem. B 1999, 103, 3570.

- Cawkwell, M.J.; Sewell, T.D.; Zheng, L.; Thompson, D.L. Shock-induced shear bands in an energetic molecular crystal: Application of shock-front absorbing boundary conditions to molecular dynamics simulations. Phys. Rev. B 2008, 78, 014107.

- Bedrov, D.; Hooper, J.B.; Smith, G.D.; Sewell, T.D. Shock-induced transformations in crystalline RDX: A uniaxial constant-stress Hugoniostat molecular dynamics simulation study. J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 131, 034712.

- Cawkwell, M.J.; Ramos, K.J.; Hooks, D.E.; Sewell, T.D. Homogeneous dislocation nucleation in cyclotrimethylene trinitramine under shock loading. J. Appl. Phys. 2010, 107, 063512.

- Bidault, X.; Chaudhuri, S. A flexible-molecule force field to model and study hexanitrohexaazaisowurtzitane (CL-20)-polymorphism under extreme conditions. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 39649.

- Agrawal, P.M.; Rice, B.M.; Zheng, L.Q.; Thompson, D.L. Molecular dynamics simulations of hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-s-triazine (RDX) using a combined Sorescu-Rice-Thompson AMBER force field. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 26185–26188.

- Agrawal, P.M.; Rice, B.M.; Zheng, L.Q.; Velardez, G.F.; Thompson, D.L. Molecular dynamics simulations of the melting of 1,3,3-trinitroazetidine. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 110, 5721–5726.

- Boyd, S.; Gravelle, M.; Politzer, P. Nonreactive molecular dynamics force field for crystalline hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine. J. Chem. Phys. 2006, 124, 104508.

- Gee, R.H.; Roszak, S.; Balasubramanian, K.; Fried, L.E. Ab initio based force field and molecular dynamics simulations of crystalline TATB. J. Chem. Phys. 2004, 120, 15.

- Bedrov, D.; Borodin, O.; Smith, G.D.; Sewell, T.D.; Dattelbaum, D.M.; Stevens, L.L. A molecular dynamics simulation study of crystalline 1,3,5-triamino-2,4,6-trinitrobenzene as a function of pressure and temperature. J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 131, 224703.

- Kroonblawd, M.P.; Sewell, T.D. Theoretical determination of anisotropic thermal conductivity for crystalline 1,3,5-triamino-2,4,6-trinitrobenzene (TATB). J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 139, 074503.

- Taylor, D.E.; Rob, F.; Rice, B.M.; Podeszwa, R.; Szalewicz, K. A molecular dynamics study of 1,1-diamino-2,2-dinitroethylene (FOX-7) crystal using a symmetry adapted perturbation theory-based intermolecular force field. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 16629–16636.

- Neyertz, S.; Mathieu, D.; Khanniche, S.; Brown, D. An empirically optimized classical force-field for molecular simulations of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT) and 2,4-dinitrotoluene (DNT). J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 116, 8374–8381.

- Song, H.J.; Zhang, Y.G.; Li, H.; Zhou, T.T.; Huang, F.L. All-atom, non-empirical, and tailor-made force field for a-RDX from first principles. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 40518–40533.

- Mayo, S.L.; Olafson, B.D.; Goddard, W.A., III. DREIDING: A generic forcefield. J. Phys. Chem. 1990, 94, 8897–8909.

- Qian, W.; Zhang, C.Y.; Xiong, Y.; Zong, H.H.; Zhang, W.B.; Shu, Y.J. Thermal expansion of explosive molecular crystal: Anisotropy and molecular stacking. Cent. Eur. J. Energetic Mater. 2014, 11, 569–580.

- Jorgensen, W.L.; Maxwell, D.S.; Tirado-Rives, J. Development and testing of the OPLS all-atom force field on conformational energetics and properties of organic liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 11225–11236.

- Wang, C.Y.; Ni, Y.X.; Zhang, C.Y.; Xue, X.G. Crystal structure prediction of 2,4,6,8,10,12-Hexanitro- 2,4,6,8,10,12-hexaazaisowurtzitane (CL-20) by a tailor-made OPLS-AA force field. Cryst. Growth Des. 2021, 21, 3037–3046.

- Choi, S.; Prince, E. The crystal structure of cyclotrimethylenetrinitramine. Acta Crystallogr. 1972, B28, 2857–2862.

- Dlott, D.D.; Fayer, M.D. Shocked molecular solids: Vibrational up pumping, defect hot spot formation, and the onset of chemistry. J. Chem. Phys. 1990, 92, 3798.

- Qian, W.; Zhang, C.Y. Review of the phonon spectrum modelings for energetic crystals and their applications. Energetic Mater. Front. 2021, 2, 154–164.

- Dobratz, M. Properties of Chemical Explosive and Explosive Simulants; Report No. UCRL 52997; Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory: Livermore, CA, USA, 1981; pp. 19–131.

- Kolb, J.R.; Rizzo, H.F. Growth of 1,3,5-triamino-2,4,6-trinitrobenzene (TATB) I. Anisotropic thermal expansion. Propellants and Explos. 1979, 4, 10.

More

Information

Subjects:

Chemistry, Physical

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

970

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

11 Mar 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No