Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ágnes Sallay | + 2820 word(s) | 2820 | 2022-03-03 05:02:42 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | -16 word(s) | 2804 | 2022-03-10 03:48:05 | | | | |

| 3 | Conner Chen | -17 word(s) | 2803 | 2022-03-10 03:49:31 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Sallay, �. Cemetery Tourism. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20386 (accessed on 01 March 2026).

Sallay �. Cemetery Tourism. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20386. Accessed March 01, 2026.

Sallay, Ágnes. "Cemetery Tourism" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20386 (accessed March 01, 2026).

Sallay, �. (2022, March 09). Cemetery Tourism. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20386

Sallay, Ágnes. "Cemetery Tourism." Encyclopedia. Web. 09 March, 2022.

Copy Citation

Cemetery tourism (thanatourism) is a specific sub-section of dark tourism that is becoming increasingly popular. Tourists wander through burial grounds with the aim of discovering the artistic, architectural, historical, and scenic heritage that often abounds in cemeteries. The changing perception of cemeteries from a place for burial towards a cultural heritage space provides several opportunities for tourism. It enables the community to explore the development of products and services that help the destination to gain new income while preserving its heritage.

cemetery tourism

landscape architecture

urban green

green infrastructure

1. Introduction

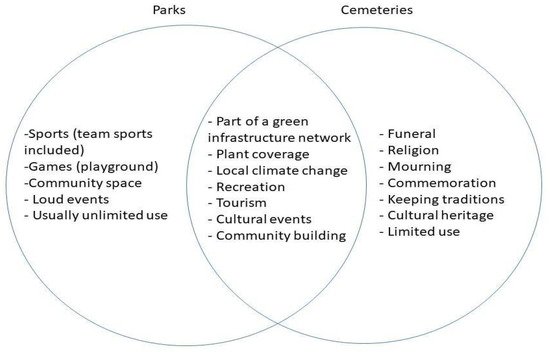

The role of urban green infrastructure or urban green areas is growing in cities as a result of population growth and urban intensification. In recent years, the COVID-19 pandemic has amplified the importance of open spaces for the local population, who spend more time in parks and other green spaces available in close proximity to their home. Cemeteries, similar to urban parks, represent an important part of the urban ecosystem, being the remaining semi-natural habitat of many species of plants and animals. However, there is no equivalence between cemeteries and public parks: while their functions and uses are similar in many respects, specificity could be mentioned as well. Cemeteries are part of the urban green infrastructure network, however, their use is limited in both time and in function. Although the use of cemeteries and parks has converged in recent decades, significant differences nevertheless exist between them (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Differences between the functions of cemeteries and public parks.

While the use of cemeteries for recreation and tourism purposes is not yet considered conventional, the rise of ‘green needs’ can be expected to increase their role in the future. On average, four million people visit Budapest cemeteries every year, and on the All Saints’ and All Souls’ Day the number of visitors can reach 1–1.5 million individuals over 2–3 days. However, no general statistics are available on the number of visitors coming to cemeteries with targeted touristic and recreational aims.

The value of cemeteries for the tourism sector lies in both the cultural aspects they offer and in the vegetation and green spaces that frame their physical realities, which can offer many services. “There are many types of cemeteries. As many as man and his follies,” writes Károly Eötvös [1] (p. 175). The layout, the use of materials, and the way of commemoration can vary from simple wooden headstones to massive stone carvings and sculptures. In Hungary, there are several legendary cemeteries where families commemorate their deceased relatives according to special traditions, and these sites have become tourist attractions. In Szatmárcseke (HU), the graveyard with its nearly 600 dark headstones representing a man’s head or a man lying in a boat is a unique sight [2]. In Balatonudvari, near the national road crossing the village, the local cemetery is protected due to its heart-shaped tombstones carved in white limestone [3] (Figure 2). The cemeteries in the region of Őrség (a cultural landscape area in Hungary near the Slovenian border) are a reminder of a unique burial tradition in the country. In Kercaszomor and other settlements in this region there exist some old and unique wooden headstones that were once erected for Calvinist deceased. This tradition is now extinct, and cemeteries with these sights are today only a tourist attraction [4]. In Hajdúböszörmény, in the former Calvinist graveyard known as the Nyugati Cemetery, we can see typical 19th century gravestones with their boat-shaped headstones [5].

Figure 2. Heart-shaped gravestones in the cemetery of Balatonudvari.

In addition to cemeteries that are special due to their burial traditions, there are other tourist attractions related to memorial places in the country: the Historical Memorial Site of the Mohács Battle, the Budaörs Military Cemetery and Peace Park (Deutsch-Ungarischer Soldatenfriedhof) [6] (Figure 3), the British Military Cemetery in Solymár, the Turkish memorial tomb of Gül Baba in Budapest (Gül baba türbéje) [7], and the Old Christian burial chambers site in Pécs, which is on the Unesco World Heritage List [8].

Figure 3. Tourists in the German–Hungarian Military Cemetery in Budaörs.

2. Cemeteries and Recreation

“Today, cemeteries are more than a place of reflection. They are a place of beauty and a place of history” [9]. A cemetery is a green open area [10], a “garden” with architectural and sculptural elements. It performs an ecological function and it is a permanent element of the landscape. It offers a chance for survival to many species of plants and birds, especially in cities, and natural “monuments” are often found among the many trees [11]. Because of their characteristics and location, throughout history cemeteries have often had a secondary function in addition to their primary one [12][13]. In the Middle Ages, church graveyards were often the central points in cities, and were the sites of fairs and festivities as well as being used for local parliaments, trials, preaching, miracle play performances, folk rites, executions, and demonstrations; however, the cemetery has always been a place of solemnity.

The majority of historical cemetery complexes are park-type areas, and are endowed with recreational facilities: clean air, silence, limited urbanization, aesthetic landscape features, and favorable climatic and bioclimatic conditions [11]. Visiting cemeteries can therefore be an opportunity for recreation. “It can be a place to get one’s thoughts rested and let them stretch themselves out. So, it is very good mentally. Yes, good to the eye and good for the head.” (man in his 40s visiting the Old Town Cemetery) [12] (p. 1). As cities become denser, green spaces are in danger of decreasing. Evensen et al. [14] (p. 76) argue that “in densified parts of cities the cemetery may be the closest greenspace accessible for every-day use” [15] (p. 2). This may have consequences for how urban cemeteries shift from being burial spaces to becoming spaces for recreation [12][13].

3. Cemeteries and Tourism

In the twentieth century, people began to travel to sites associated with death out of curiosity rather than because of their philosophical or spiritual connotations, thus initiating the origins of dark tourism. Dark tourism is the act of travel and visitation to sites, attractions, and exhibitions that have a connection to real or recreated death, suffering, or the seemingly macabre as a main theme. Tourist visits to former battlefields, slavery-heritage attractions, prisons, cemeteries, particular museum exhibitions, Holocaust sites, and disaster locations all constitute the broad realm of ‘dark tourism’ [16].

Cemetery tourism (thanatourism) is a specific sub-section of dark tourism that is becoming increasingly popular [17]. Tourists wander through burial grounds with the aim of discovering the artistic, architectural, historical, and scenic heritage that often abounds in cemeteries. The changing perception of cemeteries from a place for burial towards a cultural heritage space provides several opportunities for tourism. It enables the community to explore the development of products and services that help the destination to gain new income while preserving its heritage [18].

Cemeteries are more than just resting places for the dead; they serve a practical purpose, serve as historical markers, reflect cultural values, and impress visitors with their gorgeous designs and much more. Many people find cemeteries particularly interesting for these and other various reasons. Most cemeteries welcome the public free of charge, and many offer thematic maps, brochures, smartphone apps, audio tours, or guided tours that highlight notable graves, statues, monuments, chapels and other architectural structures of the site [9]. There are many books that have been written on the topic in recent years, for example, Stories in Stone: A Field Guide to Cemetery Symbolism and Iconography, by Douglas Keister; Beautiful Death: Art of the Cemetery, by David Robinson and Dean Koontz; and Your Guide to Cemetery Research, by Sharon DeBartolo Carmack. Today, many tourist guide books include cemeteries which may attract different groups of travelers and inspire the development of newer cemeteries.

One of the 45 European Cultural Routes of the Council of Europe is the European Cemeteries Route, certified in 2010. The European Cemeteries Route refers to cemeteries as ‘places of life’, environments that, as urban spaces, are directly linked to the history and culture of the community to which they belong and where people can find many of their references [19].

4. Touristic Activities in Cemeteries

For thousands of years, cemeteries have had the fundamental role of providing a burial place for the deceased and a place of remembrance for the bereaved. This primary function has been complemented in recent decades by secondary and tertiary functions such as providing adequate green spaces for local climate, recreation, and tourism [20]. This expansion of functions has implied a number of conflicts; how can all these traditional and new functions be managed in parallel? How can the primary needs be fully satisfied alongside the secondary and tertiary functions? Can the duty of remembering the deceased persons in cemeteries be reconciled with tourism? In many cases, the human need to say a dignified farewell to the dead has been eroded during the COVID-19 pandemic, traumatizing society and increasing the demand for cemetery use. The lockdowns due to the pandemic have affected the way cemeteries are used, with many people finding cemeteries a suitably quiet place to relax and remember their loved ones; even if they were not buried in the cemetery, they could visit in proximity. For those cemeteries where the green assets and vegetation were well established, the cemetery has become a place to meet nature.

In many places throughout Western Europe, the daily recreational use of cemeteries by the local population has become a general need and constant demand; in addition to the traditional walking activities in cemeteries, other forms of exercise such as running (in many places with separate tracks available on site), silent sports such as yoga, and dog walking are allowed under regulated conditions.

Among the tertiary touristic functions, guided walks are the most widely accepted, with visitors introduced to the values and stories of the cemeteries, mainly built heritage and grave marker interpretation. The natural or green values of cemeteries are rarely highlighted; rather, the guides include ideas about the flora and fauna of the cemeteries in other guided walks, for example in Highgate cemetery. Other tourism-related uses have been raised and implemented in different cemeteries; theater performances and concerts are more and more commonly organized, although these activities divide society and often provoke opposition from the local population, for whom the cemetery is a place of remembrance. There are various guided tours in the largest cemeteries of Budapest, where visitors can learn about the local history, the gravestones, and the famous people who rest in these cemeteries (Table 2). However, there are only a minority of guided tours that interpret the cemeteries as green spaces, presenting their living flora, and there are very few guided walks especially offered for children.

Table 2. The topics of guided walks in the largest cemeteries of Budapest.

| Organizing Institute or Company | The Name or the Theme of Walks and Guided Tours |

|---|---|

| Sétaműhely Ltd. | Trees and headstones—guided walks in the Farkasréti Cemetery On the trails of Kohanites |

| Imagine Budapest (Sétapálca Ltd.) |

A past encased in stones—a tour of the Salgótarjáni Street Jewish Cemetery |

| Nemzeti Örökség Intézete (NÖRI) National Heritage Institute |

Parcels of artists “Faster, Higher, Stronger”—Olympic medalists in the National Graveyard “On hidden pathways”—cycling tour in the National Graveyard on Fiumei Road Celebrated gipsy violinist First World War—Military tombs 19th century’s prime ministers Musician souls The artists of the “Nyugat” generation Under the spell of “Thália” The masters of Hungarian painting The death cult of the socialism The secrets of the plot 301—What do the graves tell us? The Prime Ministers of the 20th century Inventors and engineers In the footsteps of great travelers The gravestone artworks of Béla Lajta in the Jewish cemetery on Salgótarjáni Street Budapest, Budapest, so wonderful The life of an artist in sculptures Sacred depictions in funerary art of tombs In the footsteps of the Piarist Fathers and their disciples Mausoleums and the National Graveyard on Fiumei Road Those doomed to oblivion—Specific interpretation walk Graves in the garden—plants and symbols in the cemetery “That soul in me.”—Literary walk in the cemetery Immortal art—Sculptors and sculptures Remembering 1848–49 Ferenc Deák and his generation Memento ’56 History of the Jewish cemetery on Salgótarjáni street Women, Muses, Destinies Women on the trail of success Gastro moods Family walk with the little ones Go, Hungarians! Athletes and sports leaders Irregular school lessons in the cemetery Secrets of an oasis in the heart of the city—The National Graveyard on Fiumei Road (guided walk in English language) |

| Budapesti Temetkezési Intézet (BTI) Budapest Funeral Institute |

Guided walks in the Farkasréti, Óbudai and Rákoskeresztúri Cemeteries |

The touristic use of cemeteries in Western Europe was already evident in the early 2000s. The Südwest-Kirchhof in Stahnsdorf, in the immediate vicinity of Berlin, is one of the first representatives of a landscape-style forestry cemetery, and the third largest in Germany. The cemetery, which was almost abandoned at the end of the Second World War, was the subject of a strategic plan, a programme drawn up in the early 2000s by the cemetery’s advocacy association. After recognising the cemetery’s cultural, historical, and artistic importance along with its natural value, the primary objective was to bring it back into public consciousness while introducing new ways of usage. Attracting community programmes, frequent invitations of the press, and a widespread sensitisation and awareness to unique burial opportunities have brought the result that the cemetery has now been reborn. It has become a popular destination for Berliners, as have, the cemetery gardens in the city center, which are operating as active elements in the green space infrastructure as a place for recreation. The function of the funeral chapel has been extended to include cultural functions such as conferences, exhibitions, and concerts. The cemetery employs volunteers and trainees who contribute to the success of the actions through their maintenance, research, and guide work. The cemetery’s management has discovered and uses the opportunities offered by the media and the internet; periodic press conferences on the cemetery’s cultural and historical significance, its artistic values, its current events, and even a promotional film have all been regularly created [21][22].

In terms of touristic use, the Central Cemetery of Vienna (Zentralfiedhof Wien) is a particularly successful example. In addition to the traditional use of the cemetery for burial and commemoration purposes, a number of improvements with diverse goals have been made in recent years:

- Classical music and rock concerts have been organized

- Sports facilities were developed, e.g., a running track was arranged in the cemetery,

- and electric bicycles for hire and carriage rides are offered as new services

- Regular night-time opening during the month of October to give visitors a night-time view of the cemetery

- Music walks offered, with live music accompanying the walkers

- Painting course offered, where visitors can create their own artwork souvenir of the cemetery

- A cemetery museum has been opened where visitors can learn about the history of the cemetery and the famous people buried there

- Nature-focused guided walks and camps for children

- A café and gift shop have been opened at the cemetery gate

The cemetery has responded to emerging digital needs as well; anyone can take part in a self-guided walk with a QR code (Hearonymus programme), and if required, visitors can find out information about the available burial places from a digital database. Visitors can even open a digital memorial link for a deceased loved one, with the possibility of storing commemoration materials, photos, and videos about them.

All these improvements to the Central Cemetery of Vienna have been carried out in close and regular consultation with the public, taking into account their opinions and requests, to the great satisfaction of the people of Vienna as shown by the fact that the cemetery was awarded the “best place in Vienna prize” in 2020 [23].

Following foreign trends, alternative ways of using cemeteries have already appeared in Hungary. The best example of this is the National Graveyard (Fiumei Road Cemetery), where visitors can take part in numerous thematic walks which introduce them to the stories of emblematic persons buried in the cemetery and of other people with interesting background histories. A more ‘sporting’ form of visit is exists where tourists can sign up for a bike tour of the cemetery. In this largest cemetery of Budapest, it is common to see mums walking with baby strollers, young people picnicking or studying, or sportsmen exercising, running, or cycling. Because the cemetery was designed and executed as a large green park area from the beginning of its creation and is planted with many valuable trees and alleys, the recreational popularity is not surprising. The urban wildlife established in this cemetery is quite rich, and the site is comparable to a large-scale arboretum with its 56 hectares. It is important to mention the Memorial Museum operating in the National Graveyard, where visitors can learn about different aspects of Hungarian cemetery culture and burial traditions through permanent and temporary exhibitions [24].

References

- Eötvös, K. A Balatoni Utazás Vége ; Vitis Aureus Bt.: Budapest, Hungary, 2007; 175p.

- Szatmárcsekei Csónakos Fejfás Református Temető . Available online: https://reformacio.mnl.gov.hu/orokseg/szatmarcsekei_csonakos_fejfas_reformatus_temeto (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Balatonudvari—Szívalakú Sírkövek . Available online: https://www.balatonudvari.hu/balatonudvari-telepules/telepulesunk-kepekben/szivalaku-sirkovek/ (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Sökfás Temetők az Őrségben . Available online: http://guide2visit.eu/vonzerok-reszletek/sokfas-temetok-az-orsegben (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Hajdúböszörmény, Kopjafás Temető - Csónakos Fejfás Temető . Available online: https://www.turautak.com/cikkek/latnivalok/szakralis--vallasi-helyek/hajduboszormeny--kopjafas-temeto-csonakos-fejfas-temeto.html (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Katonai Temető, Budaörs . Available online: https://airbase.blog.hu/2020/10/29/katonai_temeto_budaors (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Gül Baba Türbéje. . Available online: https://gulbabaalapitvany.hu/ (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Világörökség Pécs. . Available online: https://www.pecsorokseg.hu/ (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Prater, T. Cemetery Tourism—A New Trend? Available online: https://travelinspiredliving.com/cemetery-tourism-new-trend/ (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Quinton, J.M.; Duinker, P.N. Beyond burial: Researching and managing cemeteries as urban green spaces, with examples from Canada. Environ. Rev. 2019, 27, 252–262.

- Tanaś, S. The cemetery as a part of the geography of tourism. Turyzm 2004, 14, 71–87.

- Skår, M.; Nordh, H.; Swensen, G. Green urban cemeteries: More than just parks. J. Urban. Int. Res. Placemaking Urban Sustain. 2018, 11, 362–382.

- Deering, B. In the Dead of Night. In The Power of Death: Contemporary Reflections on Death in Western Society; Blanco, M.J., Vidal, R., Eds.; Berghan Books: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 183–197.

- Evensen, K.H.; Nordh, H.; Skaar, M. Everyday use of urban cemeteries: A Norwegian case study. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 159, 76–84.

- McClymont, K.; Sinnett, D. Planning Cemeteries: Their Potential Contribution to Green Infrastructure and Ecosystem Services. Front. Sustain. Cities 2021, 3, 789925.

- Marinkovic, L. Issues of Croatian Touristic Identity in Modern Touristic Trends. J. Tour. Res. Hosp. 2016, 5. Available online: http://www.scitechnol.com/peer-review/issues-of-croatian-touristic-identity-in-modern-touristic-trends-VJGq.php?article_id=4907 (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Millán, M.G.D.; Naranjo, L.M.P.; Rojas, R.D.H.; De La Torre, M.G.M.V. Cemetery tourism in southern Spain: An analysis of demand. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 25, 37–52.

- Pliberšek, L.; Vrban, D. Cemetery as Village Tourism Development Site. In 4th International Rural Tourism Congress, Congress Proceedings; 2018; pp. 194–209. Available online: https://www.fthm.uniri.hr/images/kongres/ruralni_turizam/4/znanstveni/Plibersek_Vrban.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- European Cemeteries Route. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/cultural-routes/the-european-cemeteries-route (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Nordh, H.; Evensen, H.K. Qualities and functions ascribed to urban cemeteries across the capital cities of Scandinavia. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 33, 80–91.

- Gecséné Tar, I.; Hajdu Nagy, G. Südwest-Kirchhof, Stahnsdorf—Egy Temető Újjászületése. Tájépítészet 2005, 6, 8–11.

- Südwestkirchhof Stahnsdorf. Available online: www.suedwestkirchhof.de (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Friedhöfe Wien. Available online: www.friedhoefewien.at (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Gecse-Tar, I.; Takács, K.; Bechtold, Á. The Hungarian National Graveyard (Budapest) as a public park. Teka Kom. Urban. Archit. 2016, 44, 187–193. Available online: http://teka.pk.edu.pl/index.php/tom-xliv-2016-2/ (accessed on 12 January 2022).

More

Information

Subjects:

Horticulture

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

5.5K

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

10 Mar 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No