Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kaspars Naglis-Liepa | + 2294 word(s) | 2294 | 2022-03-03 04:39:59 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 2294 | 2022-03-04 02:16:49 | | | | |

| 3 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 2294 | 2022-03-07 04:45:34 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Naglis-Liepa, K. Consumer Behavior and Local Food Development. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20146 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Naglis-Liepa K. Consumer Behavior and Local Food Development. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20146. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Naglis-Liepa, Kaspars. "Consumer Behavior and Local Food Development" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20146 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Naglis-Liepa, K. (2022, March 03). Consumer Behavior and Local Food Development. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/20146

Naglis-Liepa, Kaspars. "Consumer Behavior and Local Food Development." Encyclopedia. Web. 03 March, 2022.

Copy Citation

The importance of local food also increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, when global food chains were facing difficulties and the local food system played a key role in agricultural sustainability and food security, although the price effect of COVID-19 restrictions was relatively small. The development of food consumption is related to the development of values in society because values determine the attitude that influences the goals set and the behavior to achieve them. The importance given to food by the consumer also determines the expected satisfaction with the product chosen and consumed.

local food

consumer behavior

1. Food and Values

In modern Western society, food is not just a basic necessity needed for biological existence, it is associated with a complex set of assessments that are subjective but at the same time influence social behavior in a densely populated area. In the context of the mainstream economy, this is a subjective assessment of utility that influences market behavior, which in turn affects the supply side (see the next section). At the same time, it is often not just a question of market behavior but of the behavior of a wider social group. According to the Value Belief Norm Theory [1], altruistic, egoistic, traditional and openness to change values create a new ecological paradigm that affects awareness by creating changes in personal norms both in the social and the private spheres. For the consumer, according to this theory, food represents certain values and belongingness to a certain social group. Of course, pro-environmental behavior patterns are complex and could be significantly influenced by contextual conditions [2][3]. Sometimes, it is not possible to define the most important value that determines a pattern of behavior. For example, consuming less meat could be attributable to both a concern for the environment and a concern for personal health. It is no surprise that egoism or a concern for health dominates. However, when choosing healthier food, consumers themselves do not consider the meaning of healthy food to be the most important thing but rather subordinate it to the moral meaning of food (act in accordance with the idea of good human behavior) [4]. Interestingly, the same moral meaning of food is also important when it comes to shopping in small shops, buying local products, not consuming meat and prioritizing quality over quantity; it basically matters how trendy it looks [5]. The prosocial behavior of consumers (participation in voluntary work, cooperation, donations or purchases of products generating some social benefit) becomes increasingly popular. Consumers who choose prosocial food (e.g., fair trade, local, climate-friendly, etc.) are also the most likely to buy organic food, which is a positive fact for retailers, the country and the whole world. At the same time, this could lead to a certain segmental contrast between prosocial and conventional food [6]. Research results suggesting that organic food users are more prosocially motivated are ambiguous. For example, a research study [7] found that organic food users were less willing to engage in supporting unfamiliar poor people and that they were significantly more severe in moral judgments. On the one hand, this could be attributed to the fact that, in some cases, specific food choices, e.g., organic food, are based on the population’s desire to belong to a group (e.g., luxury or trendy consumers), without related environmental or other prosocial motives. Or, the motive of consumer behavior is only a concern for nature; yet, humans are the cause of harm to nature and deserve a critical attitude taken towards them. However, it is clear that the German philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach’s famous saying from his essay Concerning Spiritualism and Materialism (1863), “you are what you eat”, takes a broader view. Not only does food affect our mood but we choose food according to our mood and perception of life.

2. Local Food and Inferior Goods (Utility Perspective)

Economics refers to inferior goods, which are defined as goods whose demand decreases with an increase in the consumer’s income. Basically, inferior goods are those that can be used relatively easily (cheaply) to meet basic survival needs. In this case, the utility of a good is relatively high, as is the income elasticity of demand for it. As income increases, the buyer is ready to quickly change the previous buying habits in favor of goods of higher utility. Overall, food has traditionally been considered to have inelastic demand due to its importance for household consumption, while an extremely high supply of food in the market forces consumers to make choices about a particular good. The question of consumer choice criteria is important, i.e., which criteria—economic, social and environmental—are important to the consumer’s rating of utility?

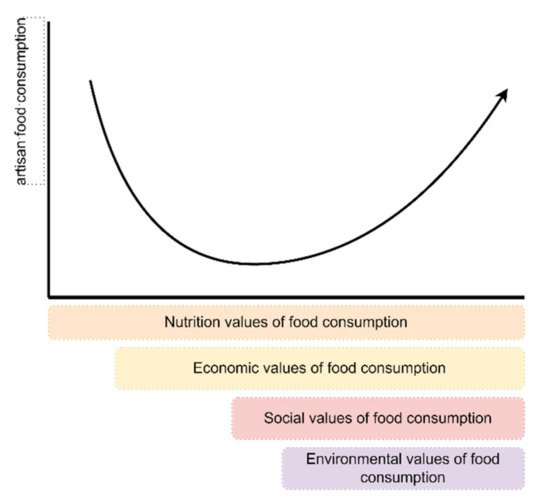

Inferior goods are characterized by the fact that they are relatively simple, often of local origin and needed to meet the so-called basic needs, and food provides nutrients for the human organism. The indigenous nature of such goods could be characterized by their relatively low price, which protects against a high level of competition. However, the very nature of such goods might also be the reason why unprocessed food is usually of local origin. It could be reasonably assumed that: (a) goods are fresher due to the shorter transport route; (b) varieties or species of food ingredients are typical of the local, customer-accepted cuisine; (c) there is greater certainty in relation to the origin of the goods and their production and processing technologies; (d) there is an emotional connection with the national product as “one’s own” versus “from the outside”. There is some contradiction: although inferior goods are inelastic in demand, they might have a certain value, which increases their utility and thus increases their elasticity, which could mean that goods of domestic origin have a higher price than those imported from abroad. At least in the case of Latvia, this is obvious [8]. A hypothesis could be put forward that, as society develops, it consumes more goods of prosocial value, while maintaining interest in relatively simple, unprocessed goods of known origin (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Artisan food and values.

Increasing the quality of food, which involves processing, inevitably raises the price, which is an essential precondition for the competitiveness of imported food that significantly increases competition through supplying a variety of goods of relatively high quality with relatively many added values such as a lower GHG emission footprint, fair trade, sustainability certificates, etc. In this part of the market segment, locally sourced foods often lose their importance, their elasticity decreases and consumers choose foods relatively easily without paying much attention to their origin. At the same time, it is a more important segment of the food market, which provides most of the everyday food basket. What matters is the “future survival” of local food and consumer decisions that influence their choices and decisions to return to the local food. In this context, different patterns of expectations [9][10][11] and the possibility of comparing consumer expectations with the reality after consuming the product are important. If the reality is better than expected, the customer will return and buy the product again, but if the expectation is not actually met, the buyer will look for an alternative product in case of this negative confirmation.

Each region has its own specific products, which are expensive and represent a relatively small proportion of daily consumption. In addition to such products, social, cultural and environmental values are also important for the diversity of nutrients and foods in everyday consumption. Food and drink have traditionally been part of the code of sacred values for many nations, including Latvians. Cultural traditions are also a factor influencing the eating habits of modern people [12]. The annual nature cycle (e.g., cumin cheese—a component of traditional holiday cuisine) is important for the consumption of only locally available products that are not offered by global food chains. The demand for such products is extremely inelastic (at least over some period), resulting in a relatively low demand and a relatively high price. In addition to the segment of inferior goods, this segment is also suitable for local food chains. At the same time, producers need to reckon with a seasonal, relatively low demand, with no significant growth potential. Medium-sized enterprises often do not consider it important to supply such products, which requires the readjustment of their production lines; therefore, there is a growing interest in this segment from home producers who provide traditionally recognizable or specific products.

3. Factors Influencing the Behavior

The topicality of values changes due to various factors. The effect of income elasticity on utility assessment was already mentioned above. At the same time, the classical economy is unable to respond to the actions of a large number of economic entities that make seemingly “illogical” decisions. To explain this, it would be necessary to realize that the individual, in particular the consumer, is not a logical decision-making machine, or, more precisely, the horizon of decision-making logic often goes beyond the perception of the factors influencing a particular issue. An explanation is an awareness that human behavior is determined by evolutionary factors. Humans are biological beings who primarily value the ability to pass on their genetic information through children. One of the most popular ideas about the dominance of this function in human behavior is Richard Dawkins’ idea of the Selfish Gene, which states that the motive for human action is determined by competition, natural selection and the replication of the most appropriate genes essential for survival [13]. On the one hand, such a view of economic processes is also in line with the basic classical postulates of economics about an economic individual. On the other hand, rational behavior means to take care of children more than of one’s own personal existence. This apparent altruistic behavior is essentially based on rational behavior and is fundamentally consistent with the goal of maximizing utility [14]. It would be logical to assume that people with children value utility differently, thereby broadening the scope of their assessment. Children, as decision-makers, are not homogeneous concerning their influence on their parents or their role as buyers. Interestingly, the age of children is important; for example, there are statistically significant differences in the consumption of organic fish by families with children under five years of age [15]. It could be assumed that parents take special care of their children, trying to provide them with the best food possible, depending on their understanding and abilities. At the same time, children are not only passive factors influencing consumption decisions. It is at a relatively early stage that children themselves begin consuming various information channels that affect their role in the shopping process [16]. Children can significantly influence parental choices [17]. At the same time, not only does the child’s own existence need to be taken into account but also other factors such as parental demographics (family type, maternal employment status), socioeconomic status, the peculiarities of family communication, child demographics (age, number of children, gender) and the product type [18].

Assuming that the choices of goods are rational, which has been doubted many times today [19], limited rationality explains the purchase of goods as a cognitively emotional process that does not lead to a rational choice of goods. Accordingly, to reap the maximum benefit of food consumption, it is necessary to consciously analyze the current situation and realize the predefined values, which is basically a kind of function of maximizing utility. This means, on the one hand, to significantly limit, in Kaneman’s [20] terminology, the operation of System 1 (automatic, fast, unconscious control) by contributing to the operation of System 2, which requires more cognitive efforts and concentration. On the other hand, conscious or mindful consumption itself is only an instrument that does not contain the attributes of assessment or decision-making. Before making consumption decisions, as suggested by the Value Belief Norm Theory discussed above, it is necessary to choose values whether they are hedonic or altruistic. It is possible to apply not only individual values but also whole value systems, such as religions or secular philosophical systems. Sabrina Helm and Brintha Subramaniam suggest [21] the concept of mindfulness borrowed from Eastern religious-philosophical systems and apply a social context to create socio-cognitive mindfulness as opposed to materialism. The mentioned authors have concluded that mindfulness and sustainable consumption are interrelated; yet, it should be noted that mindfulness is a religious and ethical concept that influences the person’s overall worldview. There is a growing movement in favor of conscious consumption, which aims to increase public awareness of purchasing decisions, taking into account the health of the consumer as well as the environmental and social aspects.

The availability of relevant information is an essential precondition for informed decision-making. Along with other aspects related to food, knowledge about healthy, ethical and resource-intensive food consumption becomes increasingly important nowadays [22].

In the case of food, the most important information is provided by labels. The EU prescribes the content and amount of information [23] that needs to appear on the packaging of goods. However, most food producers do not limit themselves to the prescribed information, recognizing that it is a means of communication with the consumer. Social media communication with the public is the norm today; bloggers on YouTube and Twitter and various other bloggers publish daily news about food, the origin of food, the production process and what food is and is not safe. The public consumes this information without drawing a line between opinions, facts, true information and fiction. In some cases, consumers choose not to know the information that indirectly indicates the negative effects of consuming the desired food (calories in sweets, carcinogens, etc.) [24]. However, the availability of information undoubtedly affects the ability of consumers to increase their wellbeing; although, in some cases, the consumer lacks the wish, possibility and time to analyze the information—for example, on the effects of specific chemical additives [24].

References

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.D.; Guagnano, G.; Kalof, L. A Value-Belief-Norm Theory of Support for Social Movements: The Case of Environmentalism; Huxley College on the Peninsulas Publications: Bellingham, WA, USA, 1991; p. 1. Available online: https://cedar.wwu.edu/hcop_facpubs/1 (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behavior: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317.

- Okumah, M.; Martin-Ortega, J.; Novo, P.; Pippa, J.; Chapman, J. Revisiting the Determinants of Pro-Environmental Behavior to Inform Land Management Policy: A Meta-Analytic Structural Equation Model Application. Land 2020, 9, 135.

- Lai, A.E.; Tirotto, F.A.; Pagliaro, S.; Fornara, F. Two Sides of the Same Coin: Environmental and Health Concern Pathways Toward Meat Consumption. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 3513.

- Kokkoris, M.D.; Stavrova, O. Meaning of food and consumer eating behaviors. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 9, 104343.

- Luomala, H.; Puska, P.; Lähdesmäki, S.M.; Kurki, S. Get some respect—Buy organic foods! When everyday consumer choices serve as prosocial status signaling. Appetite 2020, 145, 104492.

- Eskine, K.J. Wholesome Foods and Wholesome Morals? Organic Foods Reduce Prosocial Behavior and Harshen Moral Judgments. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2013, 4, 251–254.

- Nipers, A.; Pilvere, I. Assessment aof Value Added Tax Reduction Possibilities for Selected Food Groups in Latvia. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference Rural Development, Kaunas, Lithuania, 23–24 November 2017.

- Oliver, R. A Cognitive Model of the Antecedents and Consequences of Satisfaction Decisions. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 460–469.

- Oliver, R.L.; Swan, J.E. Equity and disconfirmation perceptions as influences on Merchant and product satisfaction. J. Consum. Res. 1989, 16, 372–383.

- Anderson, E.W.; Sullivan, M.W. The Antecedents and Consequences of Customer Satisfaction for Firms. Mark. Sci. 1993, 12, 125–143.

- Eglīte, A.; Kaufmane, D. Bread-Baking Traditions Incorporated in a Rural Tourism Product in Latvia. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Food and Agricultural Economics, Alanya, Turkey, 25–26 April 2019; pp. 154–161. Available online: https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20193521454 (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Dawkins, R. The Selfish Gene; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1976.

- Gowdy, J.; Seidl, I. Economic man and selfish genes: The implications of group selection for economic valuation and policy. J. Soc. Econ. 2004, 33, 343–358.

- Budhathoki, M.; Zølner, A.; Nielsen, T.; Rasmussen, M.A.; Reinbach, H.C. Intention to buy organic fish among Danish consumers: Application of the segmentation approach and the theory of planned behaviour. Aquaculture 2022, 549, 737798.

- Martensen, A.; Lars Grønholdt, L. Children’s influence on family decision making. Innov. Mark. 2008, 4, 14–22. Available online: https://www.businessperspectives.org/images/pdf/applications/publishing/templates/article/assets/2404/im_en_2008_04_Martensen.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Bertol, K.E.; Broilo, P.L.; Espartel, L.B.; Basso, K. Young children’s influence on family consumer behavior. Qual. Mark. Res. 2017, 20, 452–468.

- Sharmaa, A.; Sonwaneyb, V. Theoretical modeling of influence of children on family purchase decision making. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 133, 38–46.

- Kahneman, D. Maps of Bounded Rationality: Psychology for Behavioral Economics. Am. Econ. Rev. 2003, 93, 1449–1475.

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2011.

- Helm, S.; Subramaniam, B. Exploring Socio-Cognitive Mindfulness in the Context of Sustainable Consumption. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3692.

- Gisslevik, E. Education for Sustainable Food Consumption in Home and Consumer Studies. 2018. Available online: https://gupea.ub.gu.se/bitstream/2077/54558/1/gupea_2077_54558_1.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2022).

- The European Parliament. Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of The European Parliament and of The Council on the Provision of Food Information to Consumers, amending Regulations (EC) No 1924/2006 and (EC) No 1925/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council, and Repealing Commission Directive 87/250/EEC, Council Directive 90/496/EEC, Commission Directive 1999/10/EC, Directive 2000/13/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council, Commission Directives 2002/67/EC and 2008/5/EC and Commission Regulation (EC) No 608/2004; The Council Of The European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2013.

- Sunstein, C.R. Viewpoint: Are food labels good? Food Policy 2021, 99, 101984.

More

Information

Subjects:

Social Issues

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.6K

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

07 Mar 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No