| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gergana Zahmanova | + 3345 word(s) | 3345 | 2022-02-20 14:32:43 | | | |

| 2 | Jessie Wu | Meta information modification | 3345 | 2022-02-24 06:54:06 | | | | |

| 3 | Jessie Wu | Meta information modification | 3345 | 2022-02-24 06:59:12 | | | | |

| 4 | Jessie Wu | -3 word(s) | 3342 | 2022-02-24 07:00:56 | | |

Video Upload Options

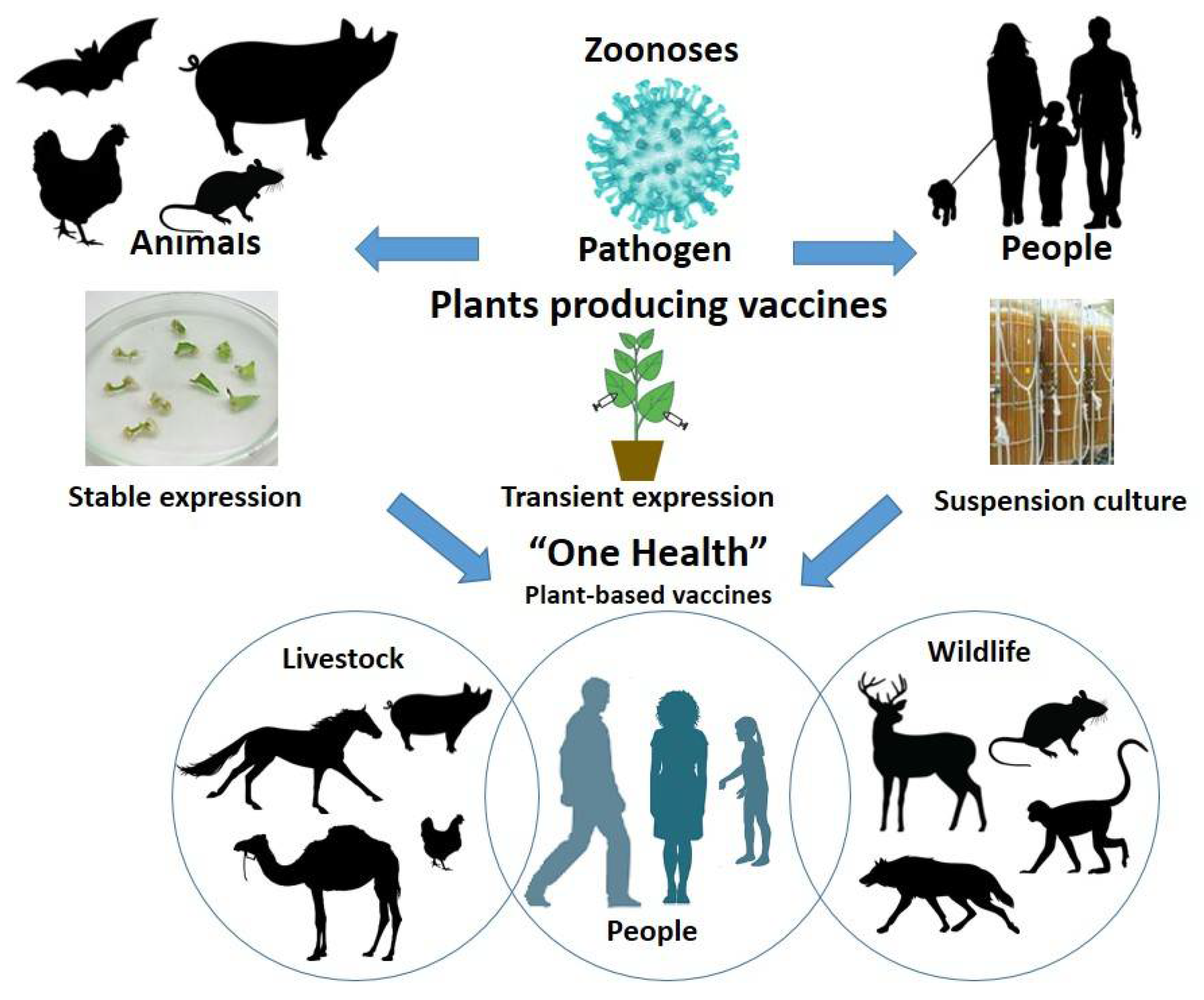

Emerging and re-emerging zoonotic diseases cause serious illness with billions of cases, and millions of deaths. The most effective way to restrict the spread of zoonotic viruses among humans and animals and prevent disease is vaccination. Recombinant proteins produced in plants offer an alternative approach for the development of safe, effective, inexpensive candidate vaccines. Current strategies are focused on the production of highly immunogenic structural proteins, which mimic the organizations of the native virion but lack the viral genetic material. These include chimeric viral peptides, subunit virus proteins, and virus-like particles (VLPs). The latter, with their ability to self-assemble and thus resemble the form of virus particles, are gaining traction among plant-based candidate vaccines against many infectious diseases.

1. Introduction

2. Plants as an Expression System for Vaccine Production

3. Virus-like Particles (VLPs) for Vaccine Development

4. Influenza Viruses

5. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

6. Concluding Remarks

The 21st Century has seen remarkable progress in the development of plant-based vaccines against viral diseases. Although the vast majority of these are centered on academic development and are still at the level of pre-clinical trials in animal models, people are also witnessing the significant achievements of vendors such as Medicago Inc and Kentucky Bioprocessing Inc, whose vaccine candidates against influenza and SARS-CoV-2 are likely to be licensed next year. Several factors are contributing to the observed progress in plant-based vaccine development. From a technical perspective, there is a shift from stable expression of viral proteins in transgenic plants to transient expression in N. benthamiana. The latter is much faster and can produce a decent yield of viral antigens within a week after infiltrating plant leaf material with an Agrobacterium suspension containing the target gene, offering the opportunity for a rapid response to the annual emergence of antigenically novel influenza strains or unexpected pandemics. Another very important factor for the current advancement of plant-based vaccines is the recent achievements in plant platforms that not only express target antigens but also facilitate the assembly of VLPs. The advantage of the plant-derived VLPs over simple expression of recombinant proteins in plants is that the former captures the antigenic epitopes in their native conformation, which results in enhanced immunogenicity and ultimately superior efficiency as a potential vaccine. Apart from the above-mentioned technological factors, the potential success of a Medicago plant-derived SARS-CoV-2 vaccine will accelerate the development of other plant vaccines in general.

Fischer and Buyel 2020 describe four factors that affect the selection of plant expression systems: time-to-market factors; the amount of time needed for research and development (R&D); scalability; and regulatory approval. Of the four, the time-to-market factors are the biggest determinant in the selection process. In addition, while plants offer an advantage during R&D (faster transient expression), the production upscaling of plant-produced proteins is usually a challenge. However, the approval of the new plant-based vaccines is likely to open new avenues for improved manufacturing.

The majority of the zoonotic viruses listed disproportionally affect developing countries. The development of new vaccines comes with a cost, which is a challenge for resource-limited countries that need these vaccines most. Plant-based vaccines carry the promise not only to be efficient in preventing zoonotic disease but also, importantly, to be cost-efficient and affordable.

Sustainable long-term cooperation and partnerships with global organizations (the WHO, the World Bank, and others) and governments must be established if plant molecular farming is to become a successful mainstream platform for vaccine generation and production.

References

- Reed, K.D. Viral Zoonoses. Ref. Module Biomed. Sci. 2018.

- Martins, S.B.; Häsler, B.; Rushton, J. Economic Aspects of Zoonoses: Impact of Zoonoses on the Food Industry. In Zoonoses—Infections Affecting Humans and Animals: Focus on Public Health Aspects; Sing, A., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 1107–1126. ISBN 978-94-017-9457-2.

- Rahman, M.T.; Sobur, M.A.; Islam, M.S.; Ievy, S.; Hossain, M.J.; El Zowalaty, M.E.; Rahman, A.T.; Ashour, H.M. Zoonotic Diseases: Etiology, Impact, and Control. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1405.

- Olival, K.J.; Hosseini, P.R.; Zambrana-Torrelio, C.; Ross, N.; Bogich, T.L.; Daszak, P. Host and Viral Traits Predict Zoonotic Spillover from Mammals. Nature 2017, 546, 646–650.

- Carroll, D.; Watson, B.; Togami, E.; Daszak, P.; Mazet, J.A.; Chrisman, C.J.; Rubin, E.M.; Wolfe, N.; Morel, C.M.; Gao, G.F.; et al. Building a Global Atlas of Zoonotic Viruses. Bull. World Health Organ. 2018, 96, 292–294.

- Belay, E.D.; Kile, J.C.; Hall, A.J.; Barton-Behravesh, C.; Parsons, M.B.; Salyer, S.J.; Walke, H. Zoonotic Disease Programs for Enhancing Global Health Security. Emerg. Infect. Dis. J. 2017, 23, S65.

- Rantsios, A.T. Zoonoses. Encycl. Food Health 2016, 645–653.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Microbial Threats. Vector-Borne Diseases: Understanding the Environmental, Human Health, and Ecological Connections, Workshop Summary; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2008.

- Gebreyes, W.A.; Dupouy-Camet, J.; Newport, M.J.; Oliveira, C.J.B.; Schlesinger, L.S.; Saif, Y.M.; Kariuki, S.; Saif, L.J.; Saville, W.; Wittum, T.; et al. The Global One Health Paradigm: Challenges and Opportunities for Tackling Infectious Diseases at the Human, Animal, and Environment Interface in Low-Resource Settings. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2014, 8, e3257.

- Schillberg, S.; Finnern, R. Plant Molecular Farming for the Production of Valuable Proteins—Critical Evaluation of Achievements and Future Challenges. J. Plant Physiol. 2021, 258–259, 153359.

- Rybicki, E.P. Plant Molecular Farming of Virus-like Nanoparticles as Vaccines and Reagents. WIREs Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2020, 12, e1587.

- Shanmugaraj, B.; Bulaon, C.J.I.; Phoolcharoen, W. Plant Molecular Farming: A Viable Platform for Recombinant Biopharmaceutical Production. Plants 2020, 9, 842.

- Rybicki, E.P. Plant-Based Vaccines against Viruses. Virol. J. 2014, 11, 205.

- Fischer, R.; Buyel, J.F. Molecular Farming—The Slope of Enlightenment. Biotechnol. Adv. 2020, 40, 107519.

- Gómez, M.L.; Huang, X.; Alvarez, D.; He, W.; Baysal, C.; Zhu, C.; Armario-Najera, V.; Perera, A.B.; Bennasser, P.C.; Saba-Mayoral, A.; et al. Contributions of the International Plant Science Community to the Fight against Human Infectious Diseases–Part 1: Epidemic and Pandemic Diseases. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 1901–1920.

- Ma, J.K.-C.; Drake, P.M.W.; Christou, P. The Production of Recombinant Pharmaceutical Proteins in Plants. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2003, 4, 794–805.

- Ward, B.J.; Makarkov, A.; Séguin, A.; Pillet, S.; Trépanier, S.; Dhaliwall, J.; Libman, M.D.; Vesikari, T.; Landry, N. Efficacy, Immunogenicity, and Safety of a Plant-Derived, Quadrivalent, Virus-like Particle Influenza Vaccine in Adults (18–64 Years) and Older Adults (≥65 Years): Two Multicentre, Randomised Phase 3 Trials. Lancet 2020, 396, 1491–1503.

- Vermij, P.; Waltz, E. USDA Approves the First Plant-Based Vaccine. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006, 24, 234.

- Lai, K.S.; Yusoff, K.; Mahmood, M. Functional Ectodomain of the Hemagglutinin-Neuraminidase Protein Is Expressed in Transgenic Tobacco Cells as a Candidate Vaccine against Newcastle Disease Virus. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2013, 1, 117–121.

- Elelyso® for Gaucher Disease. Available online: https://protalix.com/about/elelyso/ (accessed on 19 November 2021).

- Peyret, H.; Brown, J.K.M.; Lomonossoff, G.P. Improving Plant Transient Expression through the Rational Design of Synthetic 5′ and 3′ Untranslated Regions. Plant Methods 2019, 15, 108.

- Montero-Morales, L.; Steinkellner, H. Advanced Plant-Based Glycan Engineering. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2018, 6, 81.

- Drossard, J. Downstream Processing of Plant-Derived Recombinant Therapeutic Proteins. In Molecular Farming; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 217–231. ISBN 978-3-527-60363-3.

- Streatfield, S.J. Approaches to Achieve High-Level Heterologous Protein Production in Plants. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2007, 5, 2–15.

- Jutras, P.V.; D’Aoust, M.-A.; Couture, M.M.-J.; Vézina, L.-P.; Goulet, M.-C.; Michaud, D.; Sainsbury, F. Modulating Secretory Pathway PH by Proton Channel Co-Expression Can Increase Recombinant Protein Stability in Plants. Biotechnol. J. 2015, 10, 1478–1486.

- Jutras, P.V.; Dodds, I.; van der Hoorn, R.A. Proteases of Nicotiana Benthamiana: An Emerging Battle for Molecular Farming. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2020, 61, 60–65.

- Chung, Y.H.; Church, D.; Koellhoffer, E.C.; Osota, E.; Shukla, S.; Rybicki, E.P.; Pokorski, J.K.; Steinmetz, N.F. Integrating Plant Molecular Farming and Materials Research for Next-Generation Vaccines. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2021, 1–17.

- LeBlanc, Z.; Waterhouse, P.; Bally, J. Plant-Based Vaccines: The Way Ahead? Viruses 2021, 13, 5.

- Fischer, R.; Schillberg, S. Molecular Farming: Plant-Made Pharmaceuticals and Technical Proteins; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2004; ISBN 978-3-527-60363-3.

- Arntzen, C. Plant-Made Pharmaceuticals: From “Edible Vaccines” to Ebola Therapeutics. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2015, 13, 1013–1016.

- Tacket, C.O.; Mason, H.S.; Losonsky, G.; Estes, M.K.; Levine, M.M.; Arntzen, C.J. Human Immune Responses to a Novel Norwalk Virus Vaccine Delivered in Transgenic Potatoes. J. Infect. Dis. 2000, 182, 302–305.

- Tacket, C.O.; Mason, H.S.; Losonsky, G.; Clements, J.D.; Levine, M.M.; Arntzen, C.J. Immunogenicity in Humans of a Recombinant Bacterial Antigen Delivered in a Transgenic Potato. Nat. Med. 1998, 4, 607–609.

- Thanavala, Y.; Mahoney, M.; Pal, S.; Scott, A.; Richter, L.; Natarajan, N.; Goodwin, P.; Arntzen, C.J.; Mason, H.S. Immunogenicity in Humans of an Edible Vaccine for Hepatitis B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 3378–3382.

- Kolotilin, I.; Topp, E.; Cox, E.; Devriendt, B.; Conrad, U.; Joensuu, J.; Stöger, E.; Warzecha, H.; McAllister, T.; Potter, A.; et al. Plant-Based Solutions for Veterinary Immunotherapeutics and Prophylactics. Vet. Res. 2014, 45, 117.

- Liew, P.S.; Hair-Bejo, M. Farming of Plant-Based Veterinary Vaccines and Their Applications for Disease Prevention in Animals. Adv. Virol. 2015, 2015, 936940.

- Rybicki, E. History and Promise of Plant-Made Vaccines for Animals. In Prospects of Plant-Based Vaccines in Veterinary Medicine; MacDonald, J., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-3-319-90137-4.

- Keshavareddy, G.; Kumar, A.R.V.; Ramu, V.S. Methods of Plant Transformation—A Review. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2018, 7, 2656–2668.

- Barampuram, S.; Zhang, Z.J. Recent Advances in Plant Transformation. Methods Mol. Biol. Clifton 2011, 701, 1–35.

- Krenek, P.; Samajova, O.; Luptovciak, I.; Doskocilova, A.; Komis, G.; Samaj, J. Transient Plant Transformation Mediated by Agrobacterium Tumefaciens: Principles, Methods and Applications. Biotechnol. Adv. 2015, 33, 1024–1042.

- Mardanova, E.S.; Blokhina, E.A.; Tsybalova, L.M.; Peyret, H.; Lomonossoff, G.P.; Ravin, N.V. Efficient Transient Expression of Recombinant Proteins in Plants by the Novel PEff Vector Based on the Genome of Potato Virus X. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 247.

- Naseri, Z.; Khezri, G.; Davarpanah, S.J.; Ofoghi, H. Virus-Based Vectors: A New Approach for Production of Recombinant Proteins. J. Appl. Biotechnol. Rep. 2019, 6, 6–14.

- Gleba, Y.; Klimyuk, V.; Marillonnet, S. Viral Vectors for the Expression of Proteins in Plants. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2007, 18, 134–141.

- Sainsbury, F.; Thuenemann, E.C.; Lomonossoff, G.P. PEAQ: Versatile Expression Vectors for Easy and Quick Transient Expression of Heterologous Proteins in Plants. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2009, 7, 682–693.

- Venkataraman, S.; Hefferon, K. Application of Plant Viruses in Biotechnology, Medicine, and Human Health. Viruses 2021, 13, 1697.

- Peyret, H.; Lomonossoff, G.P. When Plant Virology Met Agrobacterium: The Rise of the Deconstructed Clones. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2015, 13, 1121–1135.

- Sainsbury, F. Innovation in Plant-Based Transient Protein Expression for Infectious Disease Prevention and Preparedness. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2020, 61, 110–115.

- Bally, J.; Jung, H.; Mortimer, C.; Naim, F.; Philips, J.G.; Hellens, R.; Bombarely, A.; Goodin, M.M.; Waterhouse, P.M. The Rise and Rise of Nicotiana Benthamiana: A Plant for All Reasons. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2018, 56, 405–426.

- Shahid, N.; Daniell, H. Plant-Based Oral Vaccines against Zoonotic and Non-Zoonotic Diseases. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2016, 14, 2079–2099.

- Twyman, R.M.; Christou, P. Plant Transformation Technology: Particle Bombardment. In Handbook of Plant Biotechnology; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0-470-86914-7.

- Xu, J.; Zhang, N. On the Way to Commercializing Plant Cell Culture Platform for Biopharmaceuticals: Present Status and Prospect. Pharm. Bioprocess. 2014, 2, 499–518.

- Marsian, J.; Lomonossoff, G.P. Molecular Pharming—VLPs Made in Plants. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2016, 37, 201–206.

- Zeltins, A. Protein Complexes and Virus-Like Particle Technology. Subcell. Biochem. 2018, 88, 379–405.

- Wang, C.; Zheng, X.; Gai, W.; Wong, G.; Wang, H.; Jin, H.; Feng, N.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, N.; et al. Novel Chimeric Virus-like Particles Vaccine Displaying MERS-CoV Receptor-Binding Domain Induce Specific Humoral and Cellular Immune Response in Mice. Antivir. Res. 2017, 140, 55–61.

- Chen, Q.; Lai, H. Plant-Derived Virus-like Particles as Vaccines. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2013, 9, 26–49.

- Rutkowska, D.A.; Mokoena, N.B.; Tsekoa, T.L.; Dibakwane, V.S.; O’Kennedy, M.M. Plant-Produced Chimeric Virus-like Particles—A New Generation Vaccine against African Horse Sickness. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 432.

- Zahmanova, G.; Mazalovska, M.; Takova, K.; Toneva, V.; Minkov, I.; Peyret, H.; Lomonossoff, G. Efficient Production of Chimeric Hepatitis B Virus-Like Particles Bearing an Epitope of Hepatitis E Virus Capsid by Transient Expression in Nicotiana Benthamiana. Life 2021, 11, 64.

- Nooraei, S.; Bahrulolum, H.; Hoseini, Z.S.; Katalani, C.; Hajizade, A.; Easton, A.J.; Ahmadian, G. Virus-like Particles: Preparation, Immunogenicity and Their Roles as Nanovaccines and Drug Nanocarriers. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 59.

- Lomonossoff, G.P. Virus Particles and the Uses of Such Particles in Bio- and Nanotechnology. In Recent Advances in Plant Virology; Caister Academic Press: Poole, UK, 2011.

- Mardanova, E.S.; Kotlyarov, R.Y.; Kuprianov, V.V.; Stepanova, L.A.; Tsybalova, L.M.; Lomonosoff, G.P.; Ravin, N.V. Rapid High-Yield Expression of a Candidate Influenza Vaccine Based on the Ectodomain of M2 Protein Linked to Flagellin in Plants Using Viral Vectors. BMC Biotechnol. 2015, 15, 42.

- Matić, S.; Rinaldi, R.; Masenga, V.; Noris, E. Efficient Production of Chimeric Human Papillomavirus 16 L1 Protein Bearing the M2e Influenza Epitope in Nicotiana Benthamiana Plants. BMC Biotechnol. 2011, 11, 106.

- Medicago Inc. Plant-Derived Vaccines. Biopharma Dealmakers (Biopharm Deal). 2018. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/d43747-020-00537-y (accessed on 19 November 2021).

- Pillet, S.; Aubin, É.; Trépanier, S.; Bussière, D.; Dargis, M.; Poulin, J.-F.; Yassine-Diab, B.; Ward, B.J.; Landry, N. A Plant-Derived Quadrivalent Virus like Particle Influenza Vaccine Induces Cross-Reactive Antibody and T Cell Response in Healthy Adults. Clin. Immunol. 2016, 168, 72–87.

- Balke, I.; Zeltins, A. Recent Advances in the Use of Plant Virus-Like Particles as Vaccines. Viruses 2020, 12, 270.

- Lefkowitz, E.J.; Dempsey, D.M.; Hendrickson, R.C.; Orton, R.J.; Siddell, S.G.; Smith, D.B. Virus Taxonomy: The Database of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D708–D717.

- Hay, A.J.; Gregory, V.; Douglas, A.R.; Lin, Y.P. The Evolution of Human Influenza Viruses. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2001, 356, 1861–1870.

- Cox, N.J.; Subbarao, K. Global Epidemiology of Influenza: Past and Present. Annu. Rev. Med. 2000, 51, 407–421.

- Krammer, F. The Human Antibody Response to Influenza A Virus Infection and Vaccination. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 383–397.

- Shao, W.; Li, X.; Goraya, M.U.; Wang, S.; Chen, J.-L. Evolution of Influenza A Virus by Mutation and Re-Assortment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1650.

- Proença-Módena, J.L.; Macedo, I.S.; Arruda, E. H5N1 Avian Influenza Virus: An Overview. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2007, 11, 125–133.

- Paget, J.; Spreeuwenberg, P.; Charu, V.; Taylor, R.J.; Iuliano, A.D.; Bresee, J.; Simonsen, L.; Viboud, C. Global Seasonal Influenza-associated Mortality Collaborator Network and GLaMOR Collaborating Teams* Global Mortality Associated with Seasonal Influenza Epidemics: New Burden Estimates and Predictors from the GLaMOR Project. J. Glob. Health 2019, 9, 020421.

- Pellerin, C. DARPA Effort Speeds Bio-Threat Response. Available online: https://www.army.mil/article/47617/darpa_effort_speeds_bio_threat_response (accessed on 19 November 2021).

- Medicago Inc. Final Short Form Prospectus. Available online: https://sec.report/otc/financial-report/93315 (accessed on 19 November 2021).

- D’Aoust, M.-A.; Lavoie, P.-O.; Couture, M.M.-J.; Trépanier, S.; Guay, J.-M.; Dargis, M.; Mongrand, S.; Landry, N.; Ward, B.J.; Vézina, L.-P. Influenza Virus-like Particles Produced by Transient Expression in Nicotiana Benthamiana Induce a Protective Immune Response against a Lethal Viral Challenge in Mice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2008, 6, 930–940.

- Landry, N.; Ward, B.J.; Trépanier, S.; Montomoli, E.; Dargis, M.; Lapini, G.; Vézina, L.-P. Preclinical and Clinical Development of Plant-Made Virus-Like Particle Vaccine against Avian H5N1 Influenza. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e15559.

- Pillet, S.; Aubin, É.; Trépanier, S.; Poulin, J.-F.; Yassine-Diab, B.; ter Meulen, J.; Ward, B.J.; Landry, N. Humoral and Cell-Mediated Immune Responses to H5N1 Plant-Made Virus-like Particle Vaccine Are Differentially Impacted by Alum and GLA-SE Adjuvants in a Phase 2 Clinical Trial. npj Vaccines 2018, 3, 3.

- Pillet, S.; Couillard, J.; Trépanier, S.; Poulin, J.-F.; Yassine-Diab, B.; Guy, B.; Ward, B.J.; Landry, N. Immunogenicity and Safety of a Quadrivalent Plant-Derived Virus like Particle Influenza Vaccine Candidate—Two Randomized Phase II Clinical Trials in 18 to 49 and ≥50 Years Old Adults. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216533.

- Tripathy, S.; Dassarma, B.; Bhattacharya, M.; Matsabisa, M.G. Plant-Based Vaccine Research Development against Viral Diseases with Emphasis on Ebola Virus Disease: A Review Study. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2021, 60, 261–267.

- Home—ClinicalTrials.Gov. Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ (accessed on 19 November 2021).

- Smith, T.; O’Kennedy, M.M.; Wandrag, D.B.R.; Adeyemi, M.; Abolnik, C. Efficacy of a Plant-Produced Virus-like Particle Vaccine in Chickens Challenged with Influenza A H6N2 Virus. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 502–512.

- Shoji, Y.; Bi, H.; Musiychuk, K.; Rhee, A.; Horsey, A.; Roy, G.; Green, B.; Shamloul, M.; Farrance, C.E.; Taggart, B.; et al. Plant-Derived Hemagglutinin Protects Ferrets against Challenge Infection with the A/Indonesia/05/05 Strain of Avian Influenza. Vaccine 2009, 27, 1087–1092.

- Shoji, Y.; Chichester, J.A.; Bi, H.; Musiychuk, K.; de la Rosa, P.; Goldschmidt, L.; Horsey, A.; Ugulava, N.; Palmer, G.A.; Mett, V.; et al. Plant-Expressed HA as a Seasonal Influenza Vaccine Candidate. Vaccine 2008, 26, 2930–2934.

- Shoji, Y.; Farrance, C.E.; Bautista, J.; Bi, H.; Musiychuk, K.; Horsey, A.; Park, H.; Jaje, J.; Green, B.J.; Shamloul, M.; et al. A Plant-Based System for Rapid Production of Influenza Vaccine Antigens. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2012, 6, 204–210.

- Shoji, Y.; Jones, R.M.; Mett, V.; Chichester, J.A.; Musiychuk, K.; Sun, X.; Tumpey, T.M.; Green, B.J.; Shamloul, M.; Norikane, J.; et al. A Plant-Produced H1N1 Trimeric Hemagglutinin Protects Mice from a Lethal Influenza Virus Challenge. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2013, 9, 553–560.

- Phan, H.T.; Pham, V.T.; Ho, T.T.; Pham, N.B.; Chu, H.H.; Vu, T.H.; Abdelwhab, E.M.; Scheibner, D.; Mettenleiter, T.C.; Hanh, T.X.; et al. Immunization with Plant-Derived Multimeric H5 Hemagglutinins Protect Chicken against Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Virus H5N1. Vaccines 2020, 8, 593.

- Phan, H.T.; Ho, T.T.; Chu, H.H.; Vu, T.H.; Gresch, U.; Conrad, U. Neutralizing Immune Responses Induced by Oligomeric H5N1-Hemagglutinins from Plants. Vet. Res. 2017, 48, 53.

- Phan, H.T.; Hause, B.; Hause, G.; Arcalis, E.; Stoger, E.; Maresch, D.; Altmann, F.; Joensuu, J.; Conrad, U. Influence of Elastin-Like Polypeptide and Hydrophobin on Recombinant Hemagglutinin Accumulations in Transgenic Tobacco Plants. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e99347.

- Phan, H.T.; Gresch, U.; Conrad, U. In Vitro-Formulated Oligomers of Strep-Tagged Avian Influenza Haemagglutinin Produced in Plants Cause Neutralizing Immune Responses. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2018, 6, 115.

- Phan, H.T.; Pohl, J.; Floss, D.M.; Rabenstein, F.; Veits, J.; Le, B.T.; Chu, H.H.; Hause, G.; Mettenleiter, T.; Conrad, U. ELPylated Haemagglutinins Produced in Tobacco Plants Induce Potentially Neutralizing Antibodies against H5N1 Viruses in Mice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2013, 11, 582–593.

- Mett, V.; Musiychuk, K.; Bi, H.; Farrance, C.E.; Horsey, A.; Ugulava, N.; Shoji, Y.; de la Rosa, P.; Palmer, G.A.; Rabindran, S.; et al. A Plant-Produced Influenza Subunit Vaccine Protects Ferrets against Virus Challenge. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2008, 2, 33–40.

- Musiychuk, K.; Stephenson, N.; Bi, H.; Farrance, C.E.; Orozovic, G.; Brodelius, M.; Brodelius, P.; Horsey, A.; Ugulava, N.; Shamloul, A.-M.; et al. A Launch Vector for the Production of Vaccine Antigens in Plants. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2007, 1, 19–25.

- Redkiewicz, P.; Sirko, A.; Kamel, K.A.; Góra-Sochacka, A. Plant Expression Systems for Production of Hemagglutinin as a Vaccine against Influenza Virus. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2014, 61, 551–560.

- Ceballo, Y.; Tiel, K.; López, A.; Cabrera, G.; Pérez, M.; Ramos, O.; Rosabal, Y.; Montero, C.; Menassa, R.; Depicker, A.; et al. High Accumulation in Tobacco Seeds of Hemagglutinin Antigen from Avian (H5N1) Influenza. Transgenic Res. 2017, 26, 775–789.

- Nahampun, H.N.; Bosworth, B.; Cunnick, J.; Mogler, M.; Wang, K. Expression of H3N2 Nucleoprotein in Maize Seeds and Immunogenicity in Mice. Plant Cell Rep. 2015, 34, 969–980.

- Thuenemann, E.C.; Lenzi, P.; Love, A.J.; Taliansky, M.; Bécares, M.; Zuñiga, S.; Enjuanes, L.; Zahmanova, G.G.; Minkov, I.N.; Matić, S.; et al. The Use of Transient Expression Systems for the Rapid Production of Virus-like Particles in Plants. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2013, 19, 5564–5573.

- Zahmanova, G.G.; Mazalovska, M.; Takova, K.H.; Toneva, V.T.; Minkov, I.N.; Mardanova, E.S.; Ravin, N.V.; Lomonossoff, G.P. Rapid High-Yield Transient Expression of Swine Hepatitis E ORF2 Capsid Proteins in Nicotiana Benthamiana Plants and Production of Chimeric Hepatitis E Virus-Like Particles Bearing the M2e Influenza Epitope. Plants 2019, 9, 29.

- Meshcheryakova, Y.A.; Eldarov, M.A.; Migunov, A.I.; Stepanova, L.A.; Repko, I.A.; Kiselev, C.I.; Lomonossoff, G.P.; Skryabin, K.G. Cowpea Mosaic Virus Chimeric Particles Bearing the Ectodomain of Matrix Protein 2 (M2E) of the Influenza a Virus: Production and Characterization. Mol. Biol. 2009, 43, 685–694.

- Petukhova, N.V.; Gasanova, T.V.; Ivanov, P.A.; Atabekov, J.G. High-Level Systemic Expression of Conserved Influenza Epitope in Plants on the Surface of Rod-Shaped Chimeric Particles. Viruses 2014, 6, 1789–1800.

- Ravin, N.V.; Kotlyarov, R.Y.; Mardanova, E.S.; Kuprianov, V.V.; Migunov, A.I.; Stepanova, L.A.; Tsybalova, L.M.; Kiselev, O.I.; Skryabin, K.G. Plant-Produced Recombinant Influenza Vaccine Based on Virus-like HBc Particles Carrying an Extracellular Domain of M2 Protein. Biochem. Mosc. 2012, 77, 33–40.

- Petukhova, N.V.; Gasanova, T.V.; Stepanova, L.A.; Rusova, O.A.; Potapchuk, M.V.; Korotkov, A.V.; Skurat, E.V.; Tsybalova, L.M.; Kiselev, O.I.; Ivanov, P.A.; et al. Immunogenicity and Protective Efficacy of Candidate Universal Influenza A Nanovaccines Produced in Plants by Tobacco Mosaic Virus-Based Vectors. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2013, 19, 5587–5600.

- Blokhina, E.A.; Mardanova, E.S.; Stepanova, L.A.; Tsybalova, L.M.; Ravin, N.V. Plant-Produced Recombinant Influenza A Virus Candidate Vaccine Based on Flagellin Linked to Conservative Fragments of M2 Protein and Hemagglutintin. Plants 2020, 9, 162.

- Barré-Sinoussi, F.; Chermann, J.C.; Rey, F.; Nugeyre, M.T.; Chamaret, S.; Gruest, J.; Dauguet, C.; Axler-Blin, C.; Vézinet-Brun, F.; Rouzioux, C.; et al. Isolation of a T-Lymphotropic Retrovirus from a Patient at Risk for Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS). Science 1983, 220, 868–871.

- Gallo, R.C.; Salahuddin, S.Z.; Popovic, M.; Shearer, G.M.; Kaplan, M.; Haynes, B.F.; Palker, T.J.; Redfield, R.; Oleske, J.; Safai, B. Frequent Detection and Isolation of Cytopathic Retroviruses (HTLV-III) from Patients with AIDS and at Risk for AIDS. Science 1984, 224, 500–503.

- Huet, T.; Cheynier, R.; Meyerhans, A.; Roelants, G.; Wain-Hobson, S. Genetic Organization of a Chimpanzee Lentivirus Related to HIV-1. Nature 1990, 345, 356–359.

- Hirsch, V.M.; Olmsted, R.A.; Murphey-Corb, M.; Purcell, R.H.; Johnson, P.R. An African Primate Lentivirus SIVsmclosely Related to HIV-2. Nature 1989, 339, 389–392.

- Sharp, P.M.; Hahn, B.H. Origins of HIV and the AIDS Pandemic. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2011, 1, a006841.

- De Cock, K.M.; Adjorlolo, G.; Ekpini, E.; Sibailly, T.; Kouadio, J.; Maran, M.; Brattegaard, K.; Vetter, K.M.; Doorly, R.; Gayle, H.D. Epidemiology and Transmission of HIV-2: Why There Is No HIV-2 Pandemic. JAMA 1993, 270, 2083–2086.

- van Schooten, J.; van Gils, M.J. HIV-1 Immunogens and Strategies to Drive Antibody Responses towards Neutralization Breadth. Retrovirology 2018, 15, 74.

- Tremouillaux-Guiller, J.; Moustafa, K.; Hefferon, K.; Gaobotse, G.; Makhzoum, A. Plant-Made HIV Vaccines and Potential Candidates. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2020, 61, 209–216.

- Scotti, N.; Buonaguro, L.; Tornesello, M.L.; Cardi, T.; Buonaguro, F.M. Plant-Based Anti-HIV-1 Strategies: Vaccine Molecules and Antiviral Approaches. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2010, 9, 925–936.

- Zolla-Pazner, S. Identifying Epitopes of HIV-1 That Induce Protective Antibodies. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004, 4, 199–210.

- Govea-Alonso, D.O.; Gómez-Cardona, E.E.; Rubio-Infante, N.; García-Hernández, A.L.; Varona-Santos, J.T.; Salgado-Bustamante, M.; Korban, S.S.; Moreno-Fierros, L.; Rosales-Mendoza, S. Production of an Antigenic C4(V3)6 Multiepitopic HIV Protein in Bacterial and Plant Systems. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2013, 113, 73–79.

- Lindh, I.; Kalbina, I.; Thulin, S.; Scherbak, N.; Sävenstrand, H.; Bråve, A.; Hinkula, J.; Strid, Å.; Andersson, S. Feeding of Mice with Arabidopsis Thaliana Expressing the HIV-1 Subtype C P24 Antigen Gives Rise to Systemic Immune Responses. APMIS 2008, 116, 985–994.

- Gonzalez-Rabade, N.; McGowan, E.G.; Zhou, F.; McCabe, M.S.; Bock, R.; Dix, P.J.; Gray, J.C.; Ma, J.K.-C. Immunogenicity of Chloroplast-Derived HIV-1 P24 and a P24-Nef Fusion Protein Following Subcutaneous and Oral Administration in Mice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2011, 9, 629–638.

- Pérez-Filgueira, D.M.; Brayfield, B.P.; Phiri, S.; Borca, M.V.; Wood, C.; Morris, T.J. Preserved Antigenicity of HIV-1 P24 Produced and Purified in High Yields from Plants Inoculated with a Tobacco Mosaic Virus (TMV)-Derived Vector. J. Virol. Methods 2004, 121, 201–208.

- McLain, L.; Durrani, Z.; Wisniewski, L.A.; Porta, C.; Lomonossoff, G.P.; Dimmock, N.J. Stimulation of Neutralizing Antibodies to Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 in Three Strains of Mice Immunized with a 22 Amino Acid Peptide of Gp41 Expressed on the Surface of a Plant Virus. Vaccine 1996, 14, 799–810.

- Guetard, D.; Greco, R.; Cervantes Gonzalez, M.; Celli, S.; Kostrzak, A.; Langlade-Demoyen, P.; Sala, F.; Wain-Hobson, S.; Sala, M. Immunogenicity and Tolerance Following HIV-1/HBV Plant-Based Oral Vaccine Administration. Vaccine 2008, 26, 4477–4485.

- Greco, R.; Michel, M.; Guetard, D.; Cervantes-Gonzalez, M.; Pelucchi, N.; Wain-Hobson, S.; Sala, F.; Sala, M. Production of Recombinant HIV-1/HBV Virus-like Particles in Nicotiana Tabacum and Arabidopsis Thaliana Plants for a Bivalent Plant-Based Vaccine. Vaccine 2007, 25, 8228–8240.

- Margolin, E.; Oh, Y.J.; Verbeek, M.; Naude, J.; Ponndorf, D.; Meshcheriakova, Y.A.; Peyret, H.; van Diepen, M.T.; Chapman, R.; Meyers, A.E.; et al. Co-expression of Human Calreticulin Significantly Improves the Production of HIV Gp140 and Other Viral Glycoproteins in Plants. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 2109–2117.

- Margolin, E.; Chapman, R.; Meyers, A.E.; van Diepen, M.T.; Ximba, P.; Hermanus, T.; Crowther, C.; Weber, B.; Morris, L.; Williamson, A.-L.; et al. Production and Immunogenicity of Soluble Plant-Produced HIV-1 Subtype C Envelope Gp140 Immunogens. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1378.