Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Andrea Piccioni | + 2203 word(s) | 2203 | 2022-02-23 05:03:40 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 2203 | 2022-02-23 08:34:43 | | | | |

| 3 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 2203 | 2022-02-23 08:35:08 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Piccioni, A. Emergency Department Overcrowding. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19785 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Piccioni A. Emergency Department Overcrowding. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19785. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Piccioni, Andrea. "Emergency Department Overcrowding" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19785 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Piccioni, A. (2022, February 23). Emergency Department Overcrowding. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19785

Piccioni, Andrea. "Emergency Department Overcrowding." Encyclopedia. Web. 23 February, 2022.

Copy Citation

It is certain and established that overcrowding represents one of the main problems that has been affecting global health and the functioning of the healthcare system in the last decades, and this is especially true for the emergency department (ED). Since 1980, overcrowding has been identified as one of the main factors limiting correct, timely, and efficient hospital care. The more recent COVID-19 pandemic contributed to the accentuation of this phenomenon, which was already well known and of international interest.

overcrowding

emergency department

length of stay

waiting time

inpatient boarding

1. Introduction

In order to proceed with a narrative analysis on overcrowding, it seems useful to provide some definitions, although defining and quantifying overcrowding is not simple [1][2].

Overcrowding is due to the imbalance of the need for emergency care and the hospital’s availability to provide the service [3][4]. It is a problem not only for the emergency department (ED), but for the entire hospital [5][6].

In this perspective, the central role of the hospital, and not just of the ED, is underlined by the definition of the American College of Emergency Physicians, where overcrowding is defined as “a situation that occurs when the identified need for emergency services exceeds available resources for patient care in ED, hospital, or both” [7].

In agreement with this definition, the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine states in turn that, when the hospitalization capacity is no longer guaranteed by the inpatient wards, an imbalance is created between patient demand and the supply that should be guaranteed by the hospital system. This determines the overcrowding of the emergency department and the access block, which are configured as two indicators of the dysfunction of the hospital system itself [8].

According to another definition, overcrowding refers to the condition leading to the dysfunction of the emergency department due to the fact that the number of patients (awaiting visit, awaiting transfer, or undergoing diagnosis and treatment) exceeds either the physical or staffing capacity of the ED [9].

Overcrowding thus appears to be simply defined as the imbalance between the constant increase in healthcare demand and the lack of hospital beds, both in the context of individual departments and in the context of the ED [1]. Overcrowding is therefore intertwined with the factors capable of determining an obstacle in the correct functioning of an ED, including the number of patients awaiting visit, transfer, diagnosis, treatment, and, above all, hospitalization.

Despite different approaches and attempts using different parameters, there is no standard measure that can quantify crowding in a univocal and effective way [10][11].

It has been comprehensively demonstrated by various studies concerning the subject that hospital crowding also causes a delay in the diagnostic process and in the start of treatment, triggering a vicious circle that feeds the overcrowding itself [12][13][14][15].

In turn, overcrowding also has a negative impact on the triage process, with an increase in the number of patients who do not access triage, an increase in the triage time itself, and an increase in the length of stay (LOS) [16][17][18].

Several studies and meta-analyses have also observed that ED overcrowding is associated with an increasing trend of leaving the ED before undergoing medical examination and treatment [19].

2. Overcrowding: The Input–Throughput–Output Model

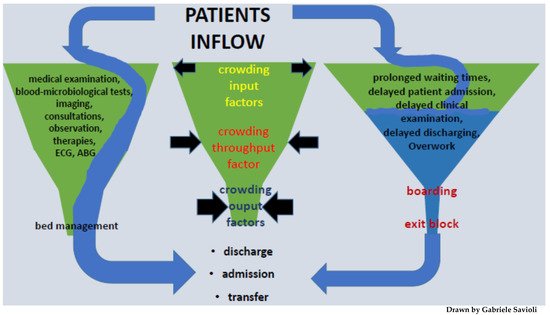

The causes of overcrowding can be classified into three categories: input, throughput, and output factors. These parameters are independent from each other, but they are interconnected and influenced by underlying contributors, making the phenomenon of overcrowding a multifactorial and complex one [2][20][21].

For a greater understanding of the crowding phenomenon, as well as to be able to consider means to quantify it and contain it, it is necessary to analyze the three aforementioned factors that contribute to its development [22].

The input–throughput–output model therefore appears useful for understanding the parameters that regulate the flow and capacity of the ED, but also represents a guideline for conceptualizing the same parameters in both the entire hospital setting and the health care system [21][22][23][24].

Input, throughput, and output factors can be defined as follows:

- -

-

Input factors: they are represented by factors determining patient access to the ED. They include the waiting time, the number of patients which arrived in the ED, as well as their severity and complexity. Input factors constitute one of the causes of crowding, but the least important [5][25][26][27][28][29]

- -

-

Throughput factors (internal factors): they are represented by the process time, meaning the time between taking charge of the patient and the outcome (diagnosis and decision: discharge, hospitalization, and transfer). They include all the complementary exams that are performed in the ED (laboratory analysis and imaging). These factors are also affected by the healthcare personnel (in terms of quality of work, shift work, burnout, drop in performance, respect for shifts, and holidays) [3][6].

- -

-

Output factors: they include patients boarding in the ED, availability of hospital beds, and the delay of transport (both internal and external) to leave the ED. The lack of hospital beds appears to be a fundamental cause of overcrowding, but so is the lack of home care. The reduction of beds (which in some realities have decreased by more than 50% in the last 20 years) is a worldwide phenomenon that has led to exit block, as well as to the collapse of the possibility of hospitalizing patients. Considering output factors, it is therefore evident that overcrowding is influenced by the fact that patients who should go to the ward are stationed in the emergency room and must continue to be assisted from a medical point of view [3][5][6].

Below, in the Table 1 is a summary of these factors and their characterization in detail [30]:

Table 1. Factors contributing to overcrowding.

| Parameter | Contributing Factors |

|---|---|

| Input | - emergencies (both medical and surgical) - visit type (both urgent and nonurgent) - ambulance arrivals - number of patients - triage score |

| Throughput | - time of processing - patients’ degree of gravity - process of triage and bed placement - bed availability (both in the ED and in the hospital) - staffing (nursing and other healthcare professionals), considering their experience and their training - other services (consultant and ancillary) - degree of boarding |

| Output | - hospital occupancy - inpatient bed shortage - transport delay (both internal and external) - staffing ratios - inefficient process of transferring care - inefficient planning of discharging patients - need of higher level of care - inpatients’ degree of gravity - lack of home care (both medical and not) |

It is also necessary to consider that:

- -

- -

- -

-

Boarding has a great importance among the causative factors of overcrowding. Boarding is in fact capable of causing a considerable dissipation of resources, which are subtracted from new patients. These resources include space, beds, diagnostic imaging techniques, but also human resources, such as hospital staff. This generates an increase in LOS and negatively affects the output factors, perpetuating the maintenance of overcrowding [21][33][34] A great number of studies provide solutions to limit boarding, although this does not represent the only causative factor of overcrowding, but its resolution would seem mandatory to limit the phenomenon [30].

- -

-

Exit block has a strong impact on overcrowding and is directly connected with the output factors. The solutions that can be promoted to alleviate exit block; however, they must not affect the patients’ outcome [35].

All the issues analyzed so far can also negatively impact the workforce, making the emergency medicine ward less attractive from a career point of view. These parameters, including overcrowding, boarding, and block, would also be able to negatively affect the quality of learning of young doctors in training [36][37].

Crowding can be effectively represented as a funnel: in the large part of the funnel are the catchment area and the input factors (number of patients, presentation methods); the process of ED patients takes place in the body of the funnel and therefore represents the throughput factors. The neck of the funnel instead represents the output factors. In the presence of crowding, it is as if the large part of the funnel is enlarged welcoming more patients while the body and the narrow part shrink, for example, due to increased process work (throughput factors) or due to lack of output factors, this causes stagnation and congestion in the flow of patients (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Diagram 1: Patient flow in emergency department.

3. Signs of Overcrowding

Signs of ED overcrowding include the following [9]:

- -

-

delay in the treatment of patients due to a lack of suitable spaces

- -

-

treatments administered in other spaces of the ED, including corridors

- -

-

prolonged stay of patients in the emergency room at the end of medical treatment, pending transfer to the ward

- -

-

inability to take care of patients transported by ambulance

- -

-

obstruction of the entry and exit routes of the ED.

4. Overcrowding: Consequences

Despite the constant redefinitions of overcrowding and block, and the proposition of numerous solutions, the problem is far from being solved [38][39].

Overcrowding has been shown to have multiple consequences on several levels.

Overcrowding determines an increase in the risk and rate of adverse events, even serious ones, of morbidity and mortality, as well as an increase in the waiting time for definitive care. This relationship between overcrowding and mortality has been highlighted by several studies, both in the pediatric and adult populations.

Regarding the pediatric population, a Korean retrospective study showed that mortality at 30 days was higher in the pediatric population whenever they were admitted to an overcrowded ED [40].

Concerning the adult population, a Canadian cohort study demonstrated that the risk of death was increased by 34% at 10 days for patients who experienced ED overcrowding during hospitalization, compared to those who did not [41].

Finally, in an Australian retrospective stratified cohort analysis, it was found that in-hospital death within 10 days of presentation was higher in the population that had presented to the ED during an overcrowded shift [42].

Considering the impact of overcrowding on the increase of adverse events, an American retrospective cohort study demonstrated an increased rate of adverse cardiovascular events in patients with both acute coronary syndrome (ACS) related and non-ACS-related chest pain admitted to ED during overcrowded periods, compared to patients who did not experience overcrowding [14].

It has also been shown that overcrowding of the ED negatively affects the timing and modalities of the triage process as well, generating an increase in waiting times and LOS, with a consequent delay in the diagnosis and in the initiation of treatment. This in turn is responsible for a greater percentage of patients abandoning an overcrowded ED without being seen, as demonstrated by multiple studies [43][44][45][46][47].

Delayed initiation of treatment and prolonged waiting times (even among patients who should benefit from immediate care) lead in turn to patient dissatisfaction [16][48][49][50] and therefore negatively impact perceived waiting times, safety, and quality of care [42][51]. This was investigated in a prospective cross-sectional study, which included 644 patients, and highlighted an association between objective measures of ED crowding and perceptions of care compromise among patients and providers [52].

Another retrospective cohort study demonstrated that a poor ED experience as measured by waiting room times, ED boarding time after admission, ED treatment time, and location of the treatment and of the waiting time, are adversely associated with ED satisfaction and predict lower satisfaction with the entire hospitalization. Moreover, patients who went to the ED during a period of overcrowding were less likely to advise others to go to ED, in comparison to those who went to the ED during a period when overcrowding was absent [53].

It is eventually necessary to consider that overcrowding has a negative impact on the welfare of the medical personnel as well, as it represents one of the most important workplace related stressors [54].

5. Overcrowding and COVID Pandemic

In some recent works, researchers have shown that, in this pandemic, input factors played a modest/ambivalent role in crowding [3][6][52]. There are two main causes in ED crowding: output and throughput factors.

In terms of output factors, crowding was determined by the phenomenon of exit block, especially by the need for unprecedented care in medium- and high-intensity wards.

In a study conducted prior to this pandemic, through tabletop simulations of a potential maxi-emergency, the research group had anticipated that such a scenario was possible. In particular, researchers had shown how wards with high- and medium-intensity care could most easily determine boarding time and access block.

Researchers believe this increment of access block is attributable to the discrepancy between the immediate and sudden need for intensive care (ICU) beds and the number of ICU beds available on the basis of national and local historical needs. However, it is important to emphasize that all patients, even those in need of low-intensity care, have struggled against access block. Therefore, the lack of beds seems to be the main cause of access block. Their opinion is that EDs are crowded when hospitals are crowded.

The waiting time for hospitalization was also prolonged because it was necessary to screen all patients before assigning them to a “clean” vs COVID-unit bed to ensure that infected (and perhaps asymptomatic) patients were not admitted to “clean” wards or wards in which the risk of infection had to remain low.

With regard to throughput factors, crowding has resulted from changes in the role of emergency physicians and EDs. Emergency departments are no longer merely where patients are sorted into specialist departments; patients are now treated and stabilized, and differential diagnostic tests.

References

- Di Somma, S.; Paladino, L.; Vaughan, L.; Lalle, I.; Magrini, L.; Magnanti, M. Overcrowding in emergency department: An international issue. Intern Emerg. Med. 2015, 10, 171–175.

- Salway, R.; Valenzuela, R.; Shoenberger, J.; Mallon, W.; Viccellio, A. Emergency Department (ED) overcrowding: Evidence-based answers to frequently asked questions. Rev. Méd. Clínica Las Condes 2017, 28, 213–219.

- Savioli, G.; Ceresa, I.F.; Novelli, V.; Ricevuti, G.; Bressan, M.A.; Oddone, E. How the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic changed the patterns of healthcare utilization by geriatric patients and the crowding: A call to action for effective solutions to the access block. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2021, 1–12.

- Pitts, S.R.; Pines, J.M.; Handrigan, M.T.; Kellermann, A.L. National trends in emergency department occupancy, 2001 to 2008: Effect of inpatient admissions versus emergency department practice intensity. Ann Emerg Med. 2012, 60, 679–686.e3.

- Richardson, D.B.; Mountain, D. Myths versus facts in emergency department overcrowding and hospital access block. Med. J. Aust. 2009, 190, 369–374.

- Savioli, G.; Ceresa, I.; Guarnone, R.; Muzzi, A.; Novelli, V.; Ricevuti, G.; Iotti, G.; Bressan, M.; Oddone, E. Impact of Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic on Crowding: A Call to Action for Effective Solutions to “Access Block”. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 22, 860–870.

- Emergency Medicine Practice Commitee, ACEP. Emergency Department Overcrowding: High Impact Solutions; ACEP: Irving, TX, USA, 2016.

- Australasian College for Emergency. Medicine Position Statement; Australasian College for Emergency: Melbourne, Australia, 2019.

- Australasian College for Emergency Medicine. P02 Policy on Standard Terminology; ACEM: Melbourne, Australia, 2014.

- Solberg, L.I.; Asplin, B.R.; Weinick, R.M.; Magid, D.J. Emergency department crowding: Consensus development of potential measures. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2003, 42, 824–834.

- Pines, J.M. Emergency Department Crowding in California: A Silent Killer? Ann. Emerg. Med. 2013, 61, 612–614.

- Ackroyd-Stolarz, S.; Guernsey, J.R.; MacKinnon, N.J.; Kovacs, G. The association between a prolonged stay in the emergency department and adverse events in older patients admitted to hospital: A retrospective cohort study. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2011, 20, 564–569.

- Hong, K.J.; Shin, S.D.; Song, K.J.; Cha, W.C.; Cho, J.S. Association between ED crowding and delay in resuscitation effort. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2013, 31, 509–515.

- Pines, J.M.; Pollack, C.V., Jr.; Diercks, D.B.; Chang, A.M.; Shofer, F.S.; Hollander, J. The Association Between Emergency Department Crowding and Adverse Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Chest Pain. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2009, 16, 617–625.

- Pines, J.M.; Shofer, F.S.; Isserman, J.A.; Abbuhl, S.B.; Mills, A. The Effect of Emergency Department Crowding on Analgesia in Patients with Back Pain in Two Hospitals. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2010, 17, 276–283.

- van der Linden, M.C.; Meester, B.E.; van der Linden, N. Emergency department crowding affects triage processes. Int. Emerg. Nurs. Nov. 2016, 29, 27–31.

- Fitzgerald, G.; Jelinek, G.A.; Scott, D.; Gerdtz, M.F. Emergency department triage revisited. Emerg. Med. J. 2010, 27, 86–92.

- Göransson, K.E.; Ehrenberg, A.; Marklund, B.; Ehnfors, M. Emergency department triage: Is there a link between nurses’ personal characteristics and accuracy in triage decisions? Accid. Emerg. Nurs. 2006, 14, 83–88.

- Carter, E.J.; Pouch, S.M.; Larson, E.L. The Relationship Between Emergency Department Crowding and Patient Outcomes: A Systematic Review. J. Nurs. Sch. 2014, 46, 106–115.

- Rabin, E.; Kocher, K.; McClelland, M.; Pines, J.; Hwang, U.; Rathlev, N.; Asplin, B.; Trueger, N.S.; Weber, E. Solutions to Emergency Department ‘Boarding’ And Crowding Are Underused and May Need to Be Legislated. Health Aff. 2012, 31, 1757–1766.

- Office USGA. Hospital Emergency Departments: Crowding Continues to Occur, and Some Patients Wait Longer than Recommended Time Frames. Available online: https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-09-347 (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Asplin, B.R.; Magid, D.J.; Rhodes, K.V.; Solberg, L.I.; Lurie, N.; Camargo, C.A., Jr. A conceptual model of emergency department crowding. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2003, 42, 173–180.

- Rathlev, N.K.; Chessare, J.; Olshaker, J.; Obendorfer, D.; Mehta, S.D.; Rothenhaus, T.; Crespo, S.; Magauran, B.; Davidson, K.; Shemin, R.; et al. Time Series Analysis of Variables Associated with Daily Mean Emergency Department Length of Stay. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2007, 49, 265–271.

- Hoot, N.R.; Aronsky, D. Systematic Review of Emergency Department Crowding: Causes, Effects, and Solutions. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2008, 52, 126–136.e1.

- Nagree, Y.; Ercleve, T.N.O.; Sprivulis, P.C. After-hours general practice clinics are unlikely to reduce low acuity patient attendances to metropolitan Perth emergency departments. Aust. Health Rev. 2004, 28, 285–291.

- Dent, A.W.; Phillips, G.; Chenhall, A.J.; McGregor, L.R. The heaviest repeat users of an inner city emergency department are not general practice patients. Emerg. Med. 2003, 15, 322–329.

- Sprivulis, P. Estimation of the general practice workload of a metropolitan teaching hospital emergency department. Emerg. Med. 2003, 15, 32–37.

- Colineaux, H.; Pelissier, F.; Pourcel, L.; Lang, T.; Kelly-Irving, M.; Azema, O.; Charpentier, S.; Lamy, S. Why are people increasingly attending the emergency department? A study of the French healthcare system. Emerg. Med. J. 2019, 36, 548–553.

- Hwang, U.; McCarthy, M.L.; Aronsky, D.; Asplin, B.; Crane, P.W.; Craven, C.K.; Epstein, S.K.; Fee, C.; Handel, D.A.; Pines, J.M.; et al. Measures of Crowding in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2011, 18, 527–538.

- Kenny, J.F.; Chang, B.C.; Hemmert, K.C. Factors Affecting Emergency Department Crowding. Emerg. Med. Clin. North Am. 2020, 38, 573–587.

- Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Hospital-Based Emergency Care: At the Breaking Point; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; 424p, Available online: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/11621/hospital-based-emergency-care-at-the-breaking-point (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Sayah, A.; Rogers, L.; Devarajan, K.; Kingsley-Rocker, L.; Lobon, L.F.; Minimizing, E.D. Waiting Times and Improving Patient Flow and Experience of Care. Emerg. Med. Int. 2014, 2014, 981472.

- Derose, S.F.; Gabayan, G.Z.; Chiu, V.Y.; Yiu, S.C.; Sun, B.C. Emergency Department Crowding Predicts Admission Length-of-Stay but Not Mortality in a Large Health System. Med. Care 2014, 52, 602–611.

- Nippak, P.M.D.; Isaac, W.W.; Ikeda-Douglas, C.J.; Marion, A.M.; Vandenbroek, M. Is there a relation between emergency department and inpatient lengths of stay? Can. J. Rural Med. 2014, 19, 12–20.

- Mason, S.; Knowles, E.; Boyle, A. Exit block in emergency departments: A rapid evidence review. Emerg. Med. J. 2016, 34, 46–51.

- Celenza, T.; Bharath, J.; Scop, J. Attitudes toward careers in emergency medicine. EMA Emerg. Med. Australas 2012, 24, 11.

- Jelinek, G.A.; Weiland, T.J.; Mackinlay, C. Supervision and feedback for junior medical staff in Australian emergency departments: Findings from the emergency medicine capacity assessment study. BMC Med. Educ. 2010, 10, 74.

- Walters, E.H.; Dawson, D.J. Whole-of-hospital response to admission access block: The need for a clinical revolution. Med. J. Aust. 2009, 191, 561–563.

- Scott, I.; Vaughan, L.; Bell, D. Effectiveness of acute medical units in hospitals: A systematic review. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2009, 21, 397–407.

- Cha, W.C.; Shin, S.D.; Cho, J.S.; Song, K.J.; Singer, A.J.; Kwak, Y.H. The Association Between Crowding and Mortality in Admitted Pediatric Patients from Mixed Adult-Pediatric Emergency Departments in Korea. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2011, 27, 1136–1141.

- Guttmann, A.; Schull, M.J.; Vermeulen, M.J.; Stukel, T.A. Association between waiting times and short term mortality and hospital admission after departure from emergency department: Population based cohort study from Ontario, Canada. BMJ 2011, 342, d2983.

- Richardson, D.B. Increase in patient mortality at 10 days associated with emergency department overcrowding. Med. J. Aust. 2006, 184, 213–216.

- Polevoi, S.K.; Quinn, J.V.; Kramer, N.R. Factors associated with patients who leave without being seen. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2005, 12, 232–236.

- Weiss, S.J.; Ernst, A.A.; Derlet, R.; King, R.; Bair, A.; Nick, T.G. Relationship between the National ED Overcrowding Scale and the number of patients who leave without being seen in an academic ED. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2005, 23, 288–294.

- Vieth, T.L.; Rhodes, K.V. The effect of crowding on access and quality in an academic ED. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2006, 24, 787–794.

- Asaro, P.V.; Lewis, L.M.; Boxerman, S.B. Emergency department overcrowding: Analysis of the factors of renege rate. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2007, 14, 157–162.

- Kulstad, E.B.; Hart, K.M.; Waghchoure, S. Occupancy Rates and Emergency Department Work Index Scores Correlate with Leaving Without Being Seen. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2010, 11, 324–328.

- Schull, M.J.; Vermeulen, M.; Slaughter, G.; Morrison, L.; Daly, P. Emergency department crowding and thrombolysis delays in acute myocardial infarction. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2004, 44, 577–585.

- Hwang, U.; Richardson, L.D.; Sonuyi, T.O.; Morrison, R.S. The Effect of Emergency Department Crowding on the Management of Pain in Older Adults with Hip Fracture. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2006, 54, 270–275.

- McCarthy, M.L.; Zeger, S.L.; Ding, R.; Levin, S.R.; Desmond, J.S.; Lee, J.; Aronsky, D. Crowding Delays Treatment and Lengthens Emergency Department Length of Stay, Even Among High-Acuity Patients. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2009, 54, 492–503.e4.

- Jeanmonod, D.; Jeanmonod, R. Overcrowding in the emergency department and patient safety. Vignettes Patient Saf. 2018, 2, 257. Available online: http://www.intechopen.com/books/vignettes-in-patient-safety-volume-2/overcrowding-in-the-emergency-department-and-patient-safety (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- Pines, J.M.; Garson, C.; Baxt, W.G.; Rhodes, K.V.; Shofer, F.S.; Hollander, J.E. ED crowding is associated with variable perceptions of care compromise. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2007, 14, 1176–1181.

- Pines, J.M.; Iyer, S.; Disbot, M.; Hollander, J.; Shofer, F.S.; Datner, E.M. The Effect of Emergency Department Crowding on Patient Satisfaction for Admitted Patients. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2008, 15, 825–831.

- Australasian College for Emergency Medicine. ACEM Workforce Sustainability Survey Report; ACEM Australasian College for Emergency Medicine: Melbourne, Australia, 2016.

More

Information

Subjects:

Allergy

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.7K

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

23 Feb 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No