| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Clara I Rodriguez | + 3237 word(s) | 3237 | 2022-02-22 10:18:04 | | | |

| 2 | Vicky Zhou | + 3236 word(s) | 3236 | 2022-02-22 13:19:24 | | | | |

| 3 | Vicky Zhou | + 2 word(s) | 3238 | 2022-02-22 13:20:23 | | | | |

| 4 | Vicky Zhou | + 17 word(s) | 3253 | 2022-02-22 13:23:22 | | |

Video Upload Options

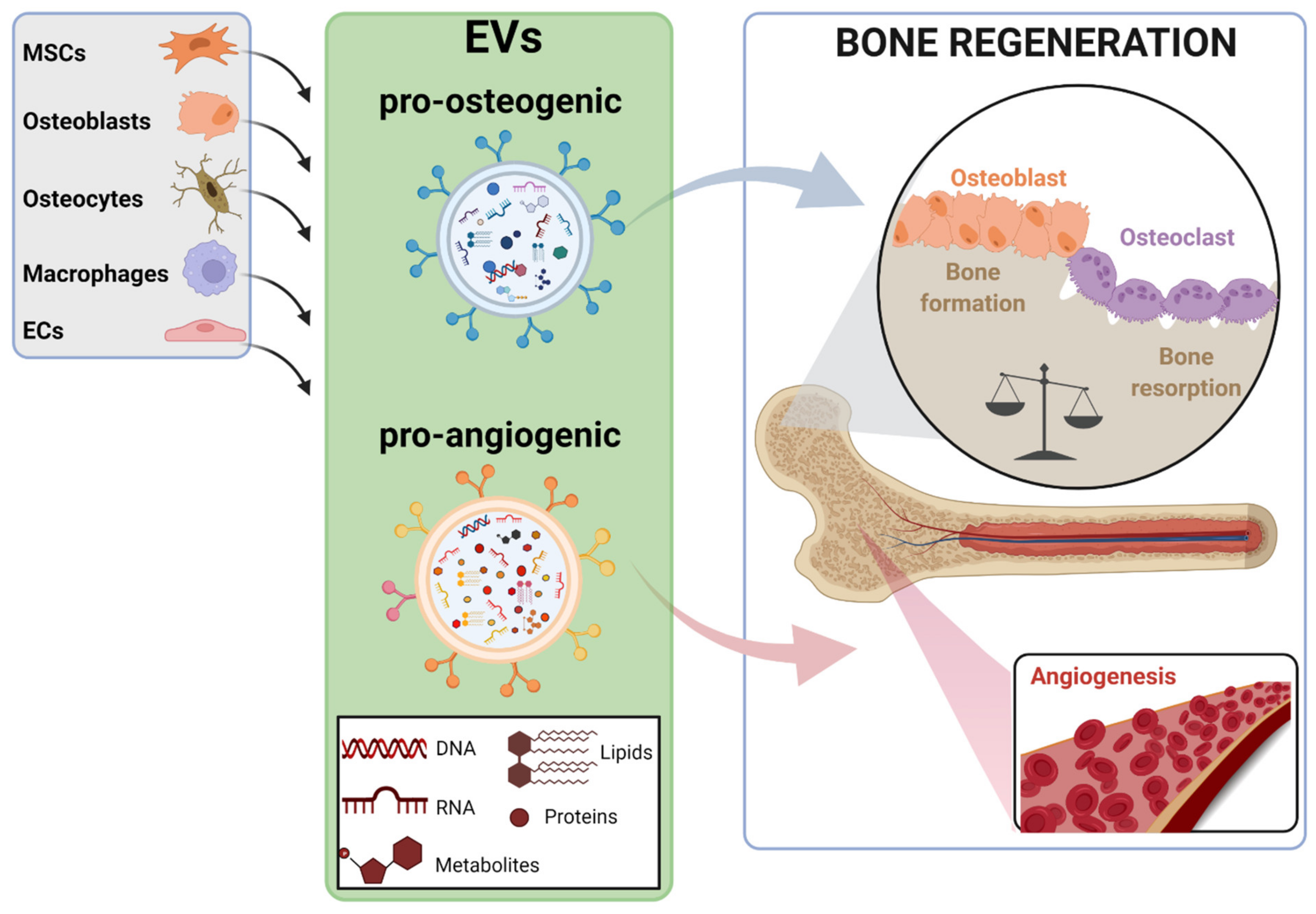

The incidence of bone-related disorders is continuously growing as the aging of the population in developing countries continues to increase. Although therapeutic interventions for bone regeneration exist, their effectiveness is questioned, especially under certain circumstances, such as critical size defects. This gap of curative options has led to the search for new and more effective therapeutic approaches for bone regeneration; among them, the possibility of using extracellular vesicles (EVs) is gaining ground. EVs are secreted, biocompatible, nano-sized vesicles that play a pivotal role as messengers between donor and target cells, mediated by their specific cargo. Evidence shows that bone-relevant cells secrete osteoanabolic EVs, whose functionality can be further improved by several strategies. This, together with the low immunogenicity of EVs and their storage advantages, make them attractive candidates for clinical prospects in bone regeneration. However, before EVs reach clinical translation, a number of concerns should be addressed. Unraveling the EVs’ mode of action in bone regeneration is one of them; the molecular mediators driving their osteoanabolic effects in acceptor cells are beginning to be uncovered. Increasing the functional and bone targeting abilities of EVs are also matters of intense research.

1. Introduction

2. EV Sources for Bone Regeneration and Mechanisms of Action

| EVs Source | Bioactive Cargo | Disease Model | Target Molecule-Pathway | Target Process | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone marrow (BM)-MSCs | miR-335 | Bone fracture | VAPB-WNT/β-CATENIN | ↓ Osteoclastogenesis & ↑ Osteogenesis |

[35] |

| miR-25 | Bone fracture | SMURF1-RUNX2 | ↑ Osteogenesis | [36] | |

| NID1 | Femoral defects | Myosin-10 | ↑ Angiogenesis | [37] | |

| mir-29a | Wild type mice | VASH1 | ↑ Angiogenesis & ↑ Osteogenesis |

[38] | |

| Aged BM-MSCs | mir-128-3p | Bone fracture | SMAD5 | ↓ Osteogenesis | [39] |

| Umbilical cord (UC)-MSCs | miR-1263 | Disuse osteoporosis (OP) | MOB1-HIPPO | ↓ Apoptosis | [40] |

| miR-21 | Glucocorticoid-induced osteonecrosis of the femoral head (GIONFH) | PTEN-PI3K/AKT | ↓ Apoptosis | [41] | |

| miR-365a-5p | GIONFH | SAV1-HIPPO | ↑ Osteogenesis | [42] | |

| miR-3960 | Senile OP | unknown | ↑ Osteogenesis & ↑ Osteoclastogenesis |

[43] | |

| CLEC11A | Ovariectomized (OVX)-OP, Disuse OP, Senile OP | unknown | ↑ Osteogenesis & ↓ Osteoclastogenesis |

[44] | |

| Hypoxia-UC-MSCs | mir-126 | Bone fracture | SPRED-1 | ↑ Angiogenesis | [45] |

| ECs | miR-126 | Distraction osteogenesis | SPRED-1 | ↑ Osteogenesis & ↑ Angiogenesis |

[24] |

| miR-155 | OVX-OP | Spi1, Mitf, Socs1 | ↓ Osteoclastogenesis | [46] |

3. Novel Strategies to Improve the Bone Regenerative Potential of EVs

3.1. Enhancing the Osteoanabolic Potential of EVs

3.1.1. Preconditioning of Parent Cells

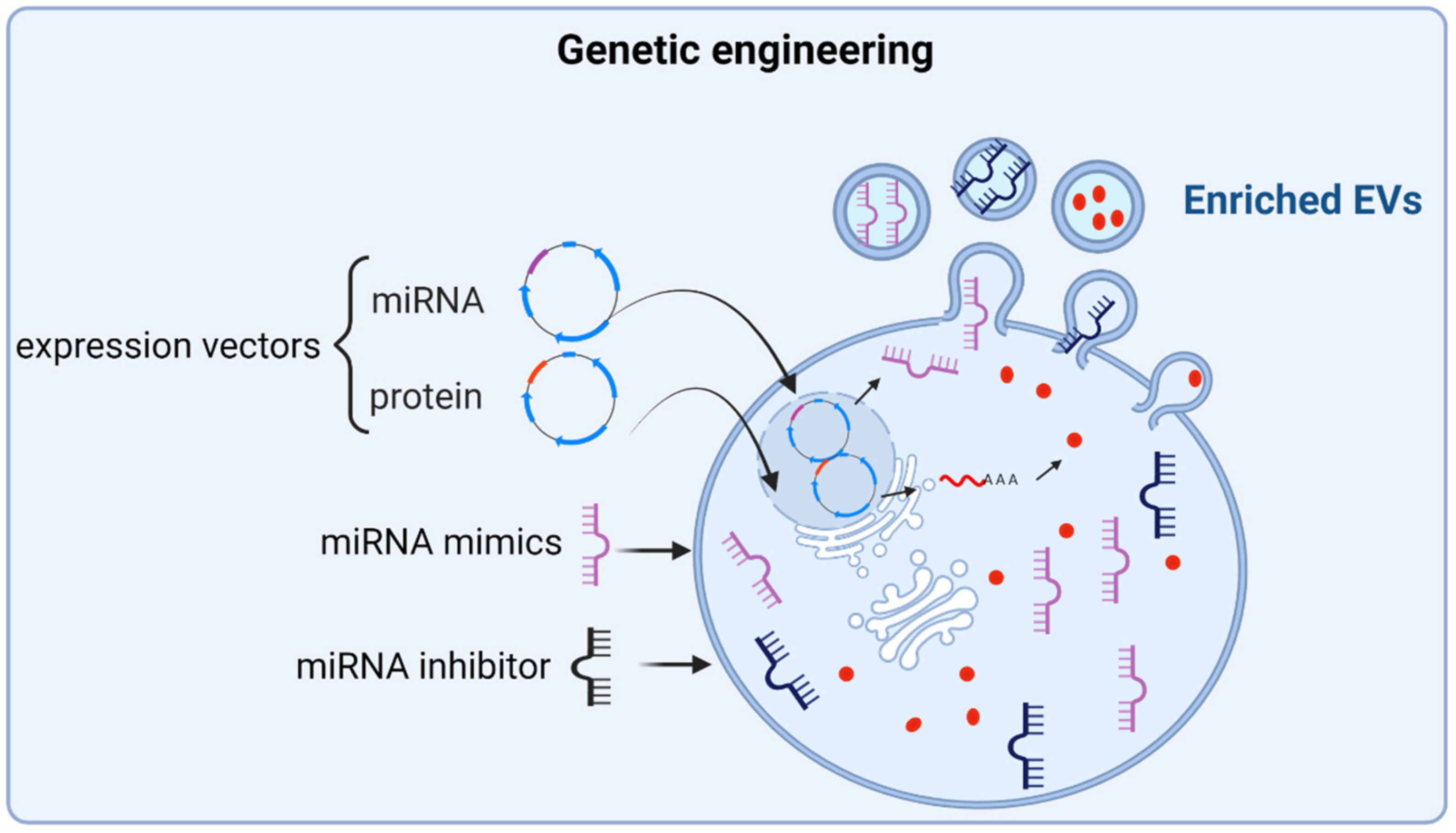

3.1.2. Engineering of Parent Cells

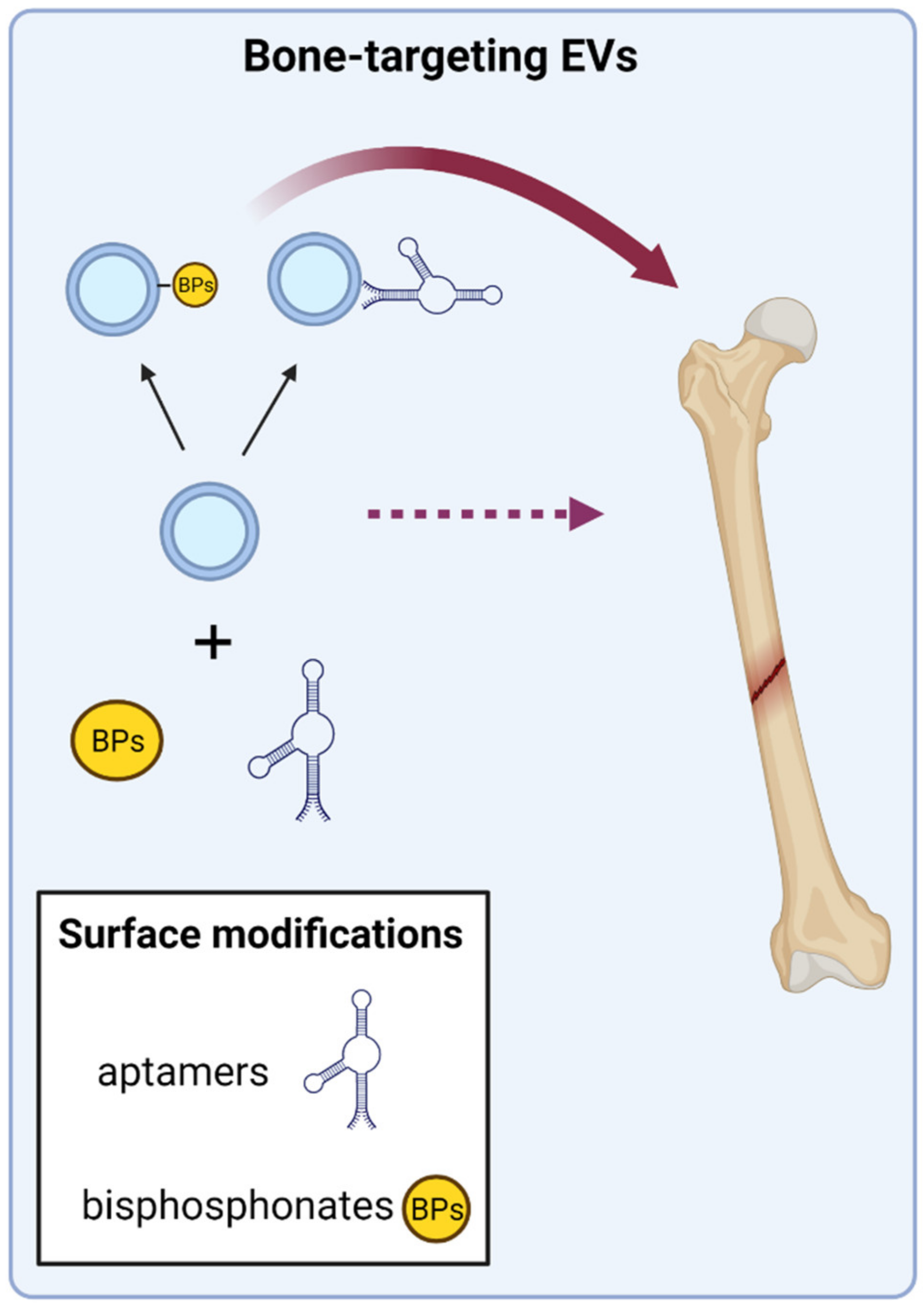

3.2. Directing EVs to Target Bone Tissue

4. Conclusions

References

- Schemitsch, E.H. Size Matters: Defining Critical in Bone Defect Size! J. Orthop. Trauma 2017, 31, S20–S22.

- Barnsley, J.; Buckland, G.; Chan, P.E.; Ong, A.; Ramos, A.S.; Baxter, M.; Laskou, F.; Dennison, E.M.; Cooper, C.; Patel, H.P. Pathophysiology and treatment of osteoporosis: Challenges for clinical practice in older people. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2021, 33, 759–773.

- Kanis, J.A.; Cooper, C.; Rizzoli, R.; Reginster, J.Y. European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos. Int. 2019, 30, 3–44.

- Kanis, J.A.; Norton, N.; Harvey, N.C.; Jacobson, T.; Johansson, H.; Lorentzon, M.; McCloskey, E.V.; Willers, C.; Borgström, F. SCOPE 2021: A new scorecard for osteoporosis in Europe. Arch. Osteoporos. 2021, 16, 82.

- Campana, V.; Milano, G.; Pagano, E.; Barba, M.; Cicione, C.; Salonna, G.; Lattanzi, W.; Logroscino, G. Bone substitutes in orthopaedic surgery: From basic science to clinical practice. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2014, 25, 2445–2461.

- Donati, D.; Zolezzi, C.; Tomba, P.; Viganò, A. Bone grafting: Historical and conceptual review, starting with an old manuscript by Vittorio Putti. Acta Orthop. 2007, 78, 19–25.

- Oryan, A.; Alidadi, S.; Moshiri, A.; Maffulli, N. Bone regenerative medicine: Classic options, novel strategies, and future directions. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2014, 9, 18.

- Macías, I.; Alcorta-Sevillano, N.; Infante, A.; Rodríguez, C.I. Cutting Edge Endogenous Promoting and Exogenous Driven Strategies for Bone Regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7724.

- Li, L.; Li, J.; Zou, Q.; Zuo, Y.; Cai, B.; Li, Y. Enhanced bone tissue regeneration of a biomimetic cellular scaffold with co-cultured MSCs-derived osteogenic and angiogenic cells. Cell Prolif. 2019, 52, e12658.

- Infante, A.; Gener, B.; Vázquez, M.; Olivares, N.; Arrieta, A.; Grau, G.; Llano, I.; Madero, L.; Bueno, A.M.; Sagastizabal, B.; et al. Reiterative infusions of MSCs improve pediatric osteogenesis imperfecta eliciting a pro-osteogenic paracrine response: TERCELOI clinical trial. Clin. Transl. Med. 2021, 11, e265.

- Horwitz, E.M.; Prockop, D.J.; Fitzpatrick, L.A.; Koo, W.W.; Gordon, P.L.; Neel, M.; Sussman, M.; Orchard, P.; Marx, J.C.; Pyeritz, R.E.; et al. Transplantability and therapeutic effects of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal cells in children with osteogenesis imperfecta. Nat. Med. 1999, 5, 309–313.

- Götherström, C.; Westgren, M.; Shaw, S.W.; Aström, E.; Biswas, A.; Byers, P.H.; Mattar, C.N.; Graham, G.E.; Taslimi, J.; Ewald, U.; et al. Pre- and postnatal transplantation of fetal mesenchymal stem cells in osteogenesis imperfecta: A two-center experience. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2014, 3, 255–264.

- Levy, O.; Kuai, R.; Siren, E.M.J.; Bhere, D.; Milton, Y.; Nissar, N.; De Biasio, M.; Heinelt, M.; Reeve, B.; Abdi, R.; et al. Shattering barriers toward clinically meaningful MSC therapies. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba6884.

- Otsuru, S.; Gordon, P.L.; Shimono, K.; Jethva, R.; Marino, R.; Phillips, C.L.; Hofmann, T.J.; Veronesi, E.; Dominici, M.; Iwamoto, M.; et al. Transplanted bone marrow mononuclear cells and MSCs impart clinical benefit to children with osteogenesis imperfecta through different mechanisms. Blood 2012, 120, 1933–1941.

- Otsuru, S.; Desbourdes, L.; Guess, A.J.; Hofmann, T.J.; Relation, T.; Kaito, T.; Dominici, M.; Iwamoto, M.; Horwitz, E.M. Extracellular vesicles released from mesenchymal stromal cells stimulate bone growth in osteogenesis imperfecta. Cytotherapy 2018, 20, 62–73.

- Monguió-Tortajada, M.; Morón-Font, M.; Gámez-Valero, A.; Carreras-Planella, L.; Borràs, F.E.; Franquesa, M. Extracellular-Vesicle Isolation from Different Biological Fluids by Size-Exclusion Chromatography. Curr. Protoc. Stem Cell Biol. 2019, 49, e82.

- Van Niel, G.; D’Angelo, G.; Raposo, G. Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 213–228.

- Dutra Silva, J.; Su, Y.; Calfee, C.S.; Delucchi, K.L.; Weiss, D.; McAuley, D.F.; O’Kane, C.; Krasnodembskaya, A.D. Mesenchymal stromal cell extracellular vesicles rescue mitochondrial dysfunction and improve barrier integrity in clinically relevant models of ARDS. Eur. Respir. J. 2021, 58.

- Teng, F.; Fussenegger, M. Shedding Light on Extracellular Vesicle Biogenesis and Bioengineering. Adv. Sci. 2020, 8, 2003505.

- Li, M.; Liao, L.; Tian, W. Extracellular Vesicles Derived From Apoptotic Cells: An Essential Link Between Death and Regeneration. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 573511.

- Herrmann, I.K.; Wood, M.J.A.; Fuhrmann, G. Extracellular vesicles as a next-generation drug delivery platform. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 748–759.

- Parada, N.; Romero-Trujillo, A.; Georges, N.; Alcayaga-Miranda, F. Camouflage strategies for therapeutic exosomes evasion from phagocytosis. J. Adv. Res. 2021, 31, 61–74.

- Gao, M.; Gao, W.; Papadimitriou, J.M.; Zhang, C.; Gao, J.; Zheng, M. Exosomes-the enigmatic regulators of bone homeostasis. Bone Res. 2018, 6, 36.

- Jia, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Qiu, S.; Xu, J.; Chai, Y. Exosomes secreted by endothelial progenitor cells accelerate bone regeneration during distraction osteogenesis by stimulating angiogenesis. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 10, 12.

- Liu, S.; Xu, X.; Liang, S.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Qian, A.; Hu, L. The Application of MSCs-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Bone Disorders: Novel Cell-Free Therapeutic Strategy. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 619.

- Théry, C.; Witwer, K.W.; Aikawa, E.; Alcaraz, M.J.; Anderson, J.D.; Andriantsitohaina, R.; Antoniou, A.; Arab, T.; Archer, F.; Atkin-Smith, G.K.; et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): A position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J. Extracell Vesicles 2018, 7, 1535750.

- Qin, Y.; Wang, L.; Gao, Z.; Chen, G.; Zhang, C. Bone marrow stromal/stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles regulate osteoblast activity and differentiation in vitro and promote bone regeneration in vivo. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21961.

- Li, D.; Liu, J.; Guo, B.; Liang, C.; Dang, L.; Lu, C.; He, X.; Cheung, H.Y.; Xu, L.; He, B.; et al. Osteoclast-derived exosomal miR-214-3p inhibits osteoblastic bone formation. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10872.

- Kobayashi-Sun, J.; Yamamori, S.; Kondo, M.; Kuroda, J.; Ikegame, M.; Suzuki, N.; Kitamura, K.I.; Hattori, A.; Yamaguchi, M.; Kobayashi, I. Uptake of osteoblast-derived extracellular vesicles promotes the differentiation of osteoclasts in the zebrafish scale. Commun. Biol 2020, 3, 190.

- Cappariello, A.; Loftus, A.; Muraca, M.; Maurizi, A.; Rucci, N.; Teti, A. Osteoblast-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Are Biological Tools for the Delivery of Active Molecules to Bone. J. Bone Min. Res. 2018, 33, 517–533.

- Minamizaki, T.; Nakao, Y.; Irie, Y.; Ahmed, F.; Itoh, S.; Sarmin, N.; Yoshioka, H.; Nobukiyo, A.; Fujimoto, C.; Niida, S.; et al. The matrix vesicle cargo miR-125b accumulates in the bone matrix, inhibiting bone resorption in mice. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 30.

- Valadi, H.; Ekström, K.; Bossios, A.; Sjöstrand, M.; Lee, J.J.; Lötvall, J.O. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 654–659.

- Xu, J.; Chen, Y.; Yu, D.; Zhang, L.; Dou, X.; Wu, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S. Evaluation of the cargo contents and potential role of extracellular vesicles in osteoporosis. Aging 2021, 13, 19282–19292.

- Shao, J.L.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.R.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.Z.; Jiao, G.L.; Sun, G.D. Identification of Serum Exosomal MicroRNA Expression Profiling in Menopausal Females with Osteoporosis by High-throughput Sequencing. Curr. Med. Sci. 2020, 40, 1161–1169.

- Hu, H.; Wang, D.; Li, L.; Yin, H.; He, G.; Zhang, Y. Role of microRNA-335 carried by bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells-derived extracellular vesicles in bone fracture recovery. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 156.

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Jia, G. Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomal miR-25 Regulates the Ubiquitination and Degradation of Runx2 by SMURF1 to Promote Fracture Healing in Mice. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 577578.

- Chen, Q.; Shou, P.; Zheng, C.; Jiang, M.; Cao, G.; Yang, Q.; Cao, J.; Xie, N.; Velletri, T.; Zhang, X.; et al. Fate decision of mesenchymal stem cells: Adipocytes or osteoblasts? Cell Death Differ. 2016, 23, 1128–1139.

- Lu, G.D.; Cheng, P.; Liu, T.; Wang, Z. BMSC-Derived Exosomal miR-29a Promotes Angiogenesis and Osteogenesis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 608521.

- Xu, T.; Luo, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, N.; Gu, C.; Li, L.; Qian, D.; Cai, W.; Fan, J.; Yin, G. Exosomal miRNA-128-3p from mesenchymal stem cells of aged rats regulates osteogenesis and bone fracture healing by targeting Smad5. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2020, 18, 47.

- Yang, B.C.; Kuang, M.J.; Kang, J.Y.; Zhao, J.; Ma, J.X.; Ma, X.L. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes act via the miR-1263/Mob1/Hippo signaling pathway to prevent apoptosis in disuse osteoporosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 524, 883–889.

- Kuang, M.J.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, X.G.; Zhang, R.; Ma, J.X.; Wang, D.C.; Ma, X.L. Exosomes derived from Wharton’s jelly of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells reduce osteocyte apoptosis in glucocorticoid-induced osteonecrosis of the femoral head in rats via the miR-21-PTEN-AKT signalling pathway. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 15, 1861–1871.

- Kuang, M.J.; Zhang, K.H.; Qiu, J.; Wang, A.B.; Che, W.W.; Li, X.M.; Shi, D.L.; Wang, D.C. Exosomal miR-365a-5p derived from HUC-MSCs regulates osteogenesis in GIONFH through the Hippo signaling pathway. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2021, 23, 565–576.

- Hu, Y.; Xu, R.; Chen, C.Y.; Rao, S.S.; Xia, K.; Huang, J.; Yin, H.; Wang, Z.X.; Cao, J.; Liu, Z.Z.; et al. Extracellular vesicles from human umbilical cord blood ameliorate bone loss in senile osteoporotic mice. Metabolism 2019, 95, 93–101.

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ni, C.Y.; Chen, C.Y.; Rao, S.S.; Yin, H.; Huang, J.; Tan, Y.J.; Wang, Z.X.; Cao, J.; et al. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stromal cells-derived extracellular vesicles exert potent bone protective effects by CLEC11A-mediated regulation of bone metabolism. Theranostics 2020, 10, 2293–2308.

- Liu, W.; Li, L.; Rong, Y.; Qian, D.; Chen, J.; Zhou, Z.; Luo, Y.; Jiang, D.; Cheng, L.; Zhao, S.; et al. Hypoxic mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes promote bone fracture healing by the transfer of miR-126. Acta Biomater. 2020, 103, 196–212.

- Song, H.; Li, X.; Zhao, Z.; Qian, J.; Wang, Y.; Cui, J.; Weng, W.; Cao, L.; Chen, X.; Hu, Y.; et al. Reversal of Osteoporotic Activity by Endothelial Cell-Secreted Bone Targeting and Biocompatible Exosomes. Nano Lett. 2019, 19, 3040–3048.

- Wang, X.; Thomsen, P. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived small extracellular vesicles and bone regeneration. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2021, 128, 18–36.

- Lai, C.P.; Mardini, O.; Ericsson, M.; Prabhakar, S.; Maguire, C.; Chen, J.W.; Tannous, B.A.; Breakefield, X.O. Dynamic biodistribution of extracellular vesicles in vivo using a multimodal imaging reporter. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 483–494.

- Kang, M.; Jordan, V.; Blenkiron, C.; Chamley, L.W. Biodistribution of extracellular vesicles following administration into animals: A systematic review. J. Extracell Vesicles 2021, 10, e12085.

- Lee, K.S.; Lee, J.; Kim, H.K.; Yeom, S.H.; Woo, C.H.; Jung, Y.J.; Yun, Y.E.; Park, S.Y.; Han, J.; Kim, E.; et al. Extracellular vesicles from adipose tissue-derived stem cells alleviate osteoporosis through osteoprotegerin and miR-21-5p. J. Extracell Vesicles 2021, 10, e12152.

- Huang, C.C.; Kang, M.; Lu, Y.; Shirazi, S.; Diaz, J.I.; Cooper, L.F.; Gajendrareddy, P.; Ravindran, S. Functionally engineered extracellular vesicles improve bone regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2020, 109, 182–194.

- Li, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Tang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, X.; Wu, G.; Zhou, Y. Tissue-Engineered Bone Immobilized with Human Adipose Stem Cells-Derived Exosomes Promotes Bone Regeneration. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 5240–5254.

- Wei, Y.; Tang, C.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Miron, R.J.; Zhang, Y. Extracellular vesicles derived from the mid-to-late stage of osteoblast differentiation markedly enhance osteogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 514, 252–258.

- García-Sánchez, D.; Fernández, D.; Rodríguez-Rey, J.C.; Pérez-Campo, F.M. Enhancing survival, engraftment, and osteogenic potential of mesenchymal stem cells. World J. Stem Cells 2019, 11, 748–763.

- Lu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Dunstan, C.; Roohani-Esfahani, S.; Zreiqat, H. Priming Adipose Stem Cells with Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha Preconditioning Potentiates Their Exosome Efficacy for Bone Regeneration. Tissue Eng. Part A 2017, 23, 1212–1220.

- Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Ma, Y.; Du, W.; Feng, K.; Wang, S. miR-101-loaded exosomes secreted by bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells requires the FBXW7/HIF1α/FOXP3 axis, facilitating osteogenic differentiation. J. Cell Physiol. 2021, 236, 4258–4272.

- Chen, S.; Tang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Lv, L.; Zhang, X.; Jia, L.; Zhou, Y. Exosomes derived from miR-375-overexpressing human adipose mesenchymal stem cells promote bone regeneration. Cell Prolif. 2019, 52, e12669.

- Liu, A.; Lin, D.; Zhao, H.; Chen, L.; Cai, B.; Lin, K.; Shen, S.G. Optimized BMSC-derived osteoinductive exosomes immobilized in hierarchical scaffold via lyophilization for bone repair through Bmpr2/Acvr2b competitive receptor-activated Smad pathway. Biomaterials 2021, 272, 120718.