| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Adriana Celis | + 2696 word(s) | 2696 | 2020-09-02 16:36:16 | | | |

| 2 | Felix Wu | -25 word(s) | 2671 | 2020-10-21 11:49:07 | | |

Video Upload Options

Malassezia is a lipid-dependent genus of yeasts known for being an important part of the skin mycobiota. These yeasts have been associated with the development of skin disorders and cataloged as a causal agent of systemic infections under specific conditions, making them opportunistic pathogens. Little is known about the host–microbe interactions of Malassezia spp., and unraveling this implies the implementation of infection models.

1. Introduction

Malassezia is a lipid-dependent genus of yeasts found as commensals on human and animal skin [1][2]. Under specific conditions, these yeasts have been associated with skin diseases [3], Crohn’s disease, the exacerbation of colitis [4], Parkinson’s disease [5], pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [6], and fungemia [7][8][9]. Factors determining the outcome of host–microbe interactions are multifactorial, involving environmental conditions like temperature and humidity, but also host factors and the predisposition of the host, which may be related to genetic factors and impairment in the immune response[10][11]. In addition, the virulence factors of Malassezia are likely to be involved. Malassezia spp. are generally regarded as opportunistic pathogens but how this skin commensal contributes to skin diseases remains a matter of debate. Studying the lifestyle of Malassezia spp. in a infection model is expected to contribute to unraveling this long-standing issue.

2. Infection Models as a Way to Understand Host–Microbe Interactions

2.1. In Vitro Models of Host-Microbe Interaction

In fungal infection research, the in vitro (ex vivo) models have been used to elucidate the mechanisms of interaction between fungi and their hosts. Indeed, an ex vivo model allows for the identification of the specific host tissue response to a pathogen, but it does not depict the whole host response [12][13][14]. The co-culturing of human keratinocytes with M. furfur yeasts was used to evaluate the activity of the cecropin A(1-8)–magainin 2(1-12) hybrid peptide analog P5 (an AMP). This research showed that this therapeutic alternative can indeed inhibit M. furfur growth without causing damage to keratinocytes. Moreover, AMPs can also modulate the inflammatory response of keratinocytes; this opens up the opportunity to evaluate new therapeutic alternatives in co-cultures of Malassezia and human keratinocytes, evaluating not just the drug effect on the pathogen but also the drug effect on and via the host [15]. Other studies have reported that Malassezia can induce or repress the production of cytokines in keratinocytes. The level of production depends on the species [16][17][18], the growth phase, and the hydrophobicity [19], and is affected by keratinocyte invasion and the survival of the pathogen inside the host cells [20]. In addition, it has been observed that M. pachydermatis, a zoophilic species, can invade human keratinocytes (12.1%) [21] and induce a strong inflammatory response during the first 24 h after coincubation[21][22]. In contrast, M. furfur has shown a lower induction of the inflammatory response, something that may be related to the avoidance of phagocytosis [20]. Interestingly, the presence of a capsule-like lipid layer may reduce the pro-inflammatory cytokine production in keratinocytes, as a way to evade the immune response [23].

In addition, the role of some factors that are excreted by species of Malassezia can be elucidated through in vitro model experiments. For example, the extracellular nanovesicles of M. sympodialis were co-cultured with keratinocytes and monocytes, demonstrating for the first time that these small structures are phagocytized by keratinocytes and monocytes [24]. Later, it was demonstrated that these nanovesicles play an important role in activating the keratinocytes as part of the cutaneous defense against Malassezia [25]. Furthermore, M. furfur has also been shown to secrete extracellular vesicles that can induce the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in human keratinocytes. Additionally, similar to what was reported in M. sympodialis, the vesicles secreted by M. furfur are phagocytized by keratinocytes [26].

Another in vitro model is the skin equivalent (SE) generated from the isolation and cultivation of fibroblasts and keratinocytes. This system allowed the growth of an inoculum of 1 × 102 CFU/mL of M. furfur, which grew to 1 × 104 CFU/mL, which could mean that SE may produce and release the nutrients necessary for Malassezia to grow on this surface. This model appeared to mimic the lipid production by the host since the culturing media did not contain these lipids [27], but care must be taken that growth is not due to lipids associated with yeast cells and/or carried over from lipid-rich media used for pre-culturing. Similar to SE, there are other models that may allow for the understanding of the host response to Malassezia. For example, the reconstructed human epidermis (RHE) offers the opportunity to follow the progress of the infection over time and measure products of the immune response at every time point. In this case, it has been reported that M. furfur and M. sympodialis suppressed the inflammatory response after 48 h, thereby evading the host immune system. Additionally, this model showed again that the keratinocyte response pattern depends on the Malassezia species used, indicating that virulence properties and mechanisms of pathogenesis differ between them [28].

2.2. In Vivo Models of Host–Pathogen Interactions

2.2.1. Mammalian Models of Host–Pathogen Interactions

Mammalian in vivo fungal infection models include mice, rats, guinea pigs, dogs, and rabbits [24][27][29][30]. In fungi, these models have allowed for the elucidation of the role of virulence factors, like the formation of biofilms of Candida albicans using rabbits and rats as infection models [27]. For Malassezia, the implementation of a host model has been difficult due to the weak virulence of the species of this genus. The first attempts to develop a suitable model for Malassezia failed because an infection could not be established in the animal model or the infection was resolved in a short time period. In 1940, Moore et al. inoculated M. furfur directly on the intact skin of rabbits, guinea pigs, rats, and mice, which resulted in no establishment of the infection unless they were infected by intracutaneous or intratesticular inoculation [30]. The evaluation of the efficacy of antifungal treatments against M. furfur in guinea pigs was possible but required daily direct inoculation on intact skin for one week, which caused skin alteration that resembled SD [31]. Similar results were observed for M. restricta inoculated directly on the skin surface of guinea pigs; wherein severe inflammation was observed after repeated inoculation every 24 h over 7 days. The skin inflammation lasted for 52 days and resembled SD. Furthermore, in this study, it was possible to evaluate the antifungal activity of ketoconazole and luliconazole, showing that the efficacy of ketoconazole is correlated with clinical findings using ketoconazole as an antifungal agent against Malassezia spp. For luliconazole, it was observed that this antifungal significantly reduced M. restricta rDNA copies and skin lesions. Taken together, these results demonstrated the suitability of the guinea pig, not just as an infection model, but also to evaluate antifungal activity [32].

Dogs were also used to model external otitis caused by M. pachydermatis; this was done through the instillation of M. pachydermatis inoculum into the external ear canal. The aim of this inoculation was to evaluate the activity of antifungals on external otitis development. Dogs were examined daily and a microscopical examination of ear exudate was done. The results showed the development of external otitis with an erythematous ear canal and exudate production. Additionally, abundant M. pachydermatis yeasts were recovered in cultures from the samples [33].

A couple of experiments have been conducted in rabbits, inoculated directly on the surface of the skin with or without occlusion with a plastic film over the inoculated area to favor colonization; this led to the occurrence of lesions on the skin and the appearance of mycelial structures in histological studies. Again, it was observed that, as soon as inoculation with yeast cells was discontinued, spontaneous healing occurred. It was, furthermore, evident that infection only occurred when occlusion was employed [34][35][36]. The presence of Malassezia in healthy skin and the high development of seborrheic dermatitis (SD) infections in acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) patients led to the belief that these yeasts were opportunistic [37][38]. In that way, new strategies to mimic the conditions of susceptible hosts were implemented. In 2004, Oble et al. developed a novel transgenic T-cell model in mice, in which spontaneous SD-like disease developed. Using anti-fungal staining, ovoid structures in primary lesions were observed. Furthermore, antifungal treatment resulted in the reversion of clinical symptoms. Although fungi were not isolated and characterized from the lesions, overgrowth by Malassezia spp. seems plausible, suggesting that infections only occur under conditions of severe immunological impairment [39].

Starting from this point, it is clear that animal models must have some kind of predisposition or repetitive exposure to successfully develop fungal infection with Malassezia. Yamasaki et al. developed a new deficient Mincle mouse model for Malassezia. Mincle, also known as Clec4e, is a PRR that recognizes the PAMP mannosyl-fatty acid in Malassezia. With the Mincle-deficient mice, it was demonstrated that the recognition of this PAMP induced the release of the cytokines Il-6 and TNF in the host, similarly to that observed in Malassezia-induced lesions in humans [40]. Another way of causing immunosuppression in animal models is through the employment of chemical substances like hydrocortisone and cyclophosphamide, which results in a different type of immunosuppression. The latter results in neutropenic animals [41].

2.2.2. In Vivo Alternative Models of Host–Microbe Interactions

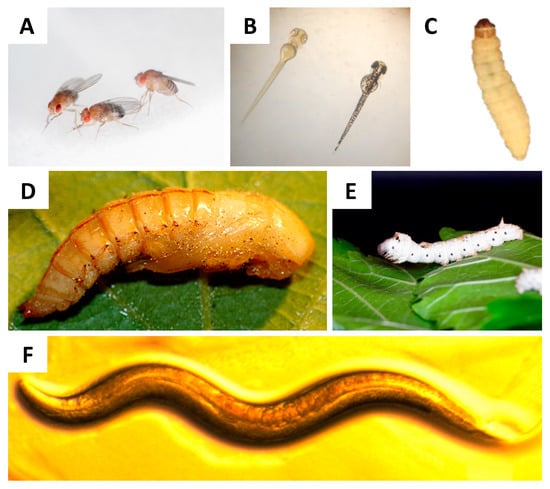

In general, in vitro studies allow for the finding of patterns that require subsequent testing and validation in in vivo infection systems; ethical considerations have especially pushed the development of new model systems. With respect to animal treatment, Russell and Burch proposed the 3Rs strategy (replacement, reduction, and refinement). This strategy leads to reducing the use of mammals and the replacement of these with alternative models; like computer, in vitro, alternative vertebrate (Danio rerio) [42], and invertebrate models [43]. In general, invertebrate alternatives used to model fungal infections like amoeboid models [44][45], Caenorhabditis elegans [46][47][48], Drosophila melanogaster [49][50][51], Tenebrio molitor [52], Bombyx mori [53] , and Galleria mellonella [54][55][56][57] (Figure 1) have gained importance, amongst others, as these present an innate immune response similar to that found in mammals. Furthermore, microbial virulence factors play similar roles in mammals and invertebrate systems [44][50][58]. The results obtained with these models correlated with results obtained in mammalian models, validating the invertebrates as infection models [50][58][59][60][61][62][63]. Furthermore, the attractive features of these models include the low cost of feeding and the higher number of organisms able to be stored in a small space and used in a single experiment [53].

Figure 1. Alternative in vivo models for host–microbe interaction studies. (A) Adult D. melanogaster fly, whose size is approximately 3 mm. Original photograph by Flickr user NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center, CC BY-SA 2.0 license. (B) Danio rerio larval size can range from 3.5 mm to 11 mm and, as can be seen, larvae are transparent, this facilitates monitoring the progress of the infection. Original photograph by Flickr user MichianaSTEM, CC BY-SA 2.0 license. (C) G. mellonella larval size ranges from 2 cm to 3 cm and its weight ranges between 200 mg and 300 mg, making it easy to manipulate and inoculate. (D) T. molitor pupae, easy to breed and the size at the 2nd instar is similar to that of G. mellonella. Original photograph by Flickr user Edithvale-Australia Insects and Spiders, CC BY-SA 2.0 license. (E) B. mori larvae, these larvae are large and their weight is in the range of 900 mg to 1000 mg. Original photograph by Flickr user Gianluigi Bertin, CC BY-SA 2.0 license. (F) C. elegans nematodes, which grow to 1 mm. Original photograph by Flickr user NIH Image Gallery, CC BY-SA 2.0 license.

In the field of Malassezia research, hardly any work has been published with alternative in vivo models and the implementation of invertebrates as model systems is very recent. In 2018, Brilhante et al. implemented for the first time the C. elegans larva as an infection model for M. pachydermatis. In this study, C. elegans larvae were exposed to M. pachydermatis by placing the larvae in plates containing the yeasts for a period of two hours at 25 °C. The viability of the nematodes was evaluated every 24 h and the results showed that, after 96 h, the nematodes exposed to the yeast had significantly higher mortality (ranging from 48% to 95%) than the control nematodes [64]. After that, in the same year, Silva et al. also evaluated the virulence of M. furfur, M. sympodialis, and M. yamatoensis under different growth conditions. The implementation of C. elegans larvae resulted in the identification of different virulence patterns depending on the lipid supplementation of the pre-culture medium. The co-culture of larvae with Malassezia spp. grown in media that was not supplemented with lipids resulted in lower larval survival. In the same study, a second model was implemented. T. molitor larvae were inoculated with a yeast suspension, and the larvae were shown, as in the case of C. elegans, to have higher survival when inoculated with M. furfur grown in a lipid-supplemented medium [65]. These two models allowed them to assess the virulence of three species of Malassezia under different growth conditions. However, more research needs to be done to understand this phenomenon.

In addition to T. molitor larvae, other insects have been implemented recently as an infection model for Malassezia. That is the case for D. melanogaster. Wild type (WT) and Toll-deficient adult flies were inoculated with five different inoculum concentrations of M. pachydermatis. The results showed that WT flies were resistant to the infection and that Toll-deficient flies inoculated with the highest inoculum concentrations showed a significantly reduced survival as compared to the control. These findings were corroborated with a decrease in fungal burden in WT flies and an absence of yeasts in histological investigations, contrasting to what was observed in the Toll-deficient flies [49]. These results demonstrated the opportunistic character of M. pachydermatis and showed the potential of the use of immune-deficient mutant flies to study the pathogenesis of Malassezia.

The G. mellonella larva was first used as a fungal infection model in 2000. In that study, the virulence of C. albicans was evaluated and compared with the effect of inoculating the larvae with Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The results showed that inoculating the larvae with the former had a lethal effect. In contrast, S. cerevisiae was shown to be pathogenic. Additionally, it was found that clinical isolates of C. albicans were more virulent as compared to reference strains (ATCC 10231, ATCC 44990, and MEN). These results correlated with findings in mammalian models [59]. After this, G. mellonella has been widely implemented as a fungal infection model to evaluate virulence[58][63][66][67][68][69][70], virulence patterns related to biofilm formation [71], co-infections [60], pathogen morphogenesis [62], complex host responses [61][72][73][74][75], and antifungal susceptibility [57][76][77][78][79] at 37 °C, which is an advantage of this lepidopteran, as it can be incubated at human physiological temperatures. The results of most of these studies have been shown to correlate with results obtained in mammalian models and also in humans. Indeed, the efficacy of antifungals tested in G. mellonella larvae against Cryptococcus spp. [57] and Candida spp. [79] have been shown to correlate with results in the murine model, C. elegans larvae, and in vitro models. Even though these results are interesting, there is a need to better understand this insect. At present, there is available information related to the immune response transcriptome [80] and the miRNAs involved in the regulation of the immune response [81] that can help to evaluate the host response to a specific pathogen. All of this together makes this insect a promising tool to elucidate the complex host–microbe interactions of Malassezia.

G. mellonella has been standardized as an infection model for M. furfur CBS 1878 and M. pachydermatis CBS 1879, two isolates from skin lesions. The inoculation of larvae with these two species showed that larval survival depended on the inoculum concentration (higher inoculum concentration led to lower survival, compared to lower inoculum concentration). Additionally, a lower virulence was observed for M. furfur as compared to M. pachydermatis at 33 °C and 37 °C. This was evident by a decrease in larval survival, higher fungal burden, histological examination with a higher presence of hemocyte aggregates with melanin deposition, and a higher larval melanization, especially in larvae that were inoculated with M. pachydermatis and incubated at 37 °C. The higher virulence of M. pachydermatis was attributed to a high phospholipase activity and a high capacity of M. pachydermatis to form biofilms [82]. However, further studies are required to confirm these hypotheses. These results show that the G. mellonella larva is a suitable model and very useful to identify differences in virulence between species or strains.

References

- Juntachai, W.; Oura, T.; Murayama, S.Y.; Kajiwara, S. The lipolytic enzymes activities of Malassezia species. Med. Mycol. 2009, 47, 477–484, doi:10.1080/13693780802314825.

- Wu, G.; Zhao, H.; Li, C.; Rajapakse, M.P.; Wong, W.C.; Xu, J.; Saunders, C.W.; Reeder, N.L.; Reilman, R.A.; Scheynius, A.; et al. Genus-Wide Comparative Genomics of Malassezia Delineates Its Phylogeny, Physiology, and Niche Adaptation on Human Skin. PLoS Genet. 2015, 11, 1–26, doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005614.

- Theelen, B.; Cafarchia, C.; Gaitanis, G.; Bassukas, I.D.; Boekhout, T.; Dawson, T.L. Malassezia ecology, pathophysiology, and treatment. Med. Mycol. 2018, 56, S10–S25, doi:10.1093/mmy/myx134.

- Limon, J.J.; Tang, J.; Li, D.; Wolf, A.J.; Michelsen, K.S.; Funari, V.; Gargus, M.; Nguyen, C.; Sharma, P.; Maymi, V.I.; et al. Malassezia Is Associated with Crohn’s Disease and Exacerbates Colitis in Mouse Models. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 25, 377-388, doi:10.1016/j.chom.2019.01.007.

- Laurence, M.; Benito-León, J.; Calon, F. Malassezia and Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 758, doi:10.3389/fneur.2019.00758.

- Aykut, B.; Pushalkar, S.; Chen, R.; Li, Q.; Abengozar, R.; Kim, J.I.; Shadaloey, S.A.; Wu, D.; Preiss, P.; Verma, N.; et al. The fungal mycobiome promotes pancreatic oncogenesis via activation of MBL. Nature 2019, 574, 264–267,doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1608-2.

- Roman, J.; Bagla, P.; Ren, P.; Blanton, L.S.; Berman, M.A. Malassezia pachydermatis fungemia in an adult with multibacillary leprosy. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 2016, 12, 1–3, doi:10.1016/j.mmcr.2016.05.002.

- Ochman, E.; Podsiadło, B.; Połowniak-Pracka, H.; Hagmajer, E.; Sowiński, P. Malassezia furfur sepsis in a cancer patient. Nowotw. J. Oncol. 2004, 54, 130–134.

- Nagata, R.; Nagano, H.; Ogishima, D.; Nakamura, Y.; Hiruma, M.; Sugita, T. Transmission of the major skin microbiota, Malassezia, from mother to neonate. Pediatr. Int. 2012, 54, 350–355, doi:10.1111/j.1442-200X.2012.03563.x.

- DeAngelis, Y.M.; Gemmer, C.M.; Kaczvinsky, J.R.; Kenneally, D.C.; Schwartz, J.R.; Dawson, T.L. Three etiologic facets of dandruff and seborrheic dermatitis: Malassezia fungi, sebaceous lipids, and individual sensitivity. J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 2005, 10, 295–297, doi:10.1111/j.1087-0024.2005.10119.x.

- Borelli, D.; Jacobs, P.H.; Nall, L. Tinea versicolor: Epidemiologic, clinical, and therapeutic aspects. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1991, 25, 300–305, doi:10.1016/0190-9622(91)70198-B.

- Swearengen, J.R. Choosing the right animal model for infectious disease research. Anim. Model. Exp. Med. 2018, 1, 100–108, doi:10.1002/ame2.12020.

- Capilla, J.; Clemons, K. V.; Stevens, D.A. Animal models: An important tool in mycology. Med. Mycol. 2007, 45, 657–684, doi: 10.1080/13693780701644140.

- Van Dijck, P.; Sjollema, J.; Cammue, B.P.A.; Lagrou, K.; Berman, J.; d’Enfert, C.; Andes, D.R.; Arendrup, M.C.; Brakhage, A.A.; Calderone, R.; et al. Methodologies for in vitro and in vivo evaluation of efficacy of antifungal and antibiofilm agents and surface coatings against fungal biofilms. Microb. Cell 2018, 5, 300–326, doi:10.15698/mic2018.07.638.

- Ryu, S.; Choi, S.Y.; Acharya, S.; Chun, Y.J.; Gurley, C.; Park, Y.; Armstrong, C.A.; Song, P.I.; Kim, B.J. Antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects of cecropin A(1-8)-magainin2(1-12) hybrid peptide analog P5 against Malassezia furfur infection in human keratinocytes. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2011, 131, 1677–1683, doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.112.

- Watanabe, S.; Kano, R.; Sato, H.; Nakamura, Y.; Hasegawa, A. The effects of Malassezia yeasts on cytokine production by human keratinocytes. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2001, 116, 769–773, doi:10.1046/j.1523-1747.2001.01321.x.

- Donnarumma, G.; Perfetto, B.; Paoletti, I.; Oliviero, G.; Clavaud, C.; Del Bufalo, A.; Guéniche, A.; Jourdain, R.; Tufano, M.A.; Breton, L. Analysis of the response of human keratinocytes to Malassezia globosa and restricta strains. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2014, 306, 763–768, doi:10.1007/s00403-014-1479-1.

- Ishibashi, Y.; Sugita, T.; Nishikawa, A. Cytokine secretion profile of human keratinocytes exposed to Malassezia yeasts. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2006, 48, 400–409, doi:10.1111/j.1574-695X.2006.00163.x.

- Akaza, N.; Akamatsu, H.; Takeoka, S.; Mizutani, H.; Nakata, S.; Matsunaga, K. Increased hydrophobicity in Malassezia species correlates with increased proinflammatory cytokine expression in human keratinocytes. Med. Mycol. 2012, 87, 802–810, doi:10.3109/13693786.2012.678019.

- Baroni, A.; Perfetto, B.; Paoletti, I.; Ruocco, E.; Canozo, N.; Orlando, M.; Buommino, E. Malassezia furfur invasiveness in a keratinocyte cell line (HaCat): effects on cytoskeleton and on adhesion molecule and cytokine expression. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2001, 293, 414–419, doi:10.1007/s004030100248.

- Buommino, E.; De Filippis, A.; Parisi, A.; Nizza, S.; Martano, M.; Iovane, G.; Donnarumma, G.; Tufano, M.A.; De Martino, L. Innate immune response in human keratinocytes infected by a feline isolate of Malassezia pachydermatis. Vet. Microbiol. 2013, 163, 90–96, doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2012.12.001.

- Buommino, E.; Baroni, A.; Papulino, C.; Nocera, F.P.; Coretti, L.; Donnarumma, G.; De Filippis, A.; De Martino, L. Malassezia pachydermatis up-regulates AhR related CYP1A1 gene and epidermal barrier markers in human keratinocytes. Med. Mycol. 2018, 56, 987–993, doi:10.1093/mmy/myy004.

- Thomas, D.S.; Ingham, E.; Bojar, R.A.; Holland, K.T. In vitro modulation of human keratinocyte pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine production by the capsule of Malassezia species. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2008, 54, 203–214, doi:10.1111/j.1574-695X.2008.00468.x.

- Johansson, H.J.; Vallhov, H.; Holm, T.; Gehrmann, U.; Andersson, A.; Johansson, C.; Blom, H.; Carroni, M.; Lehtiö, J.; Scheynius, A. Extracellular nanovesicles released from the commensal yeast Malassezia sympodialis are enriched in allergens and interact with cells in human skin. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–11, doi: 0.1038/s41598-018-27451-9.

- Vallhov, H.; Johansson, C.; Veerman, R.E.; Scheynius, A. Extracellular Vesicles Released From the Skin Commensal Yeast Malassezia sympodialis Activate Human Primary Keratinocytes. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 1–11, doi:10.3389/fcimb.2020.00006.

- Zhang, Y.J.; Han, Y.; Sun, Y.Z.; Jiang, H.H.; Liu, M.; Qi, R.Q.; Gao, X.H. Extracellular vesicles derived from Malassezia furfur stimulate IL-6 production in keratinocytes as demonstrated in in vitro and in vivo models. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2019, 93, 168–175, doi:10.1016/j.jdermsci.2019.03.001.

- Holland, D.B.; Bojar, R.A.; Jeremy, A.H.T.; Ingham, E.; Holland, K.T. Microbial colonization of an in vitro model of a tissue engineered human skin equivalent - A novel approach. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2008, 279, 110–115, doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.01021.x.

- Pedrosa, A.F.; Lisboa, C.; Branco, J.; Pellevoisin, C.; Miranda, I.M.; Rodrigues, A.G. Malassezia interaction with a reconstructed human epidermis: Keratinocyte immune response. Mycoses 2019, 62, 932–936, doi:10.1111/myc.12965.

- McCarthy, M.W.; Denning, D.W.; Walsh, T.J. Future research priorities in fungal resistance. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 216, S484–S492, doi:10.1093/infdis/jix103.

- Moore, M.; Louis, S.; Pullar, A.; Hardwicke, R. LXXXIII.-MALASSEZIA FURFUR, THE CAUSE OF TINEA VERSICOLOR CULTIVATION OF THE ORGANISM AND EXPERIMENTAL PRODUCTION OF THE DISEASE. Arch Derm Syphilol 1940, 41, 253–260, doi:10.1001/archderm.1940.01490080062003.

- Van Cutsem, J.; Van Gerven, F.; Fransen, J.; Schrooten, P.; Janssen, P.A.J. The in vitro antifungal activity of ketoconazole, zinc pyrithione, and selenium sulfide against Pityrosporum and their efficacy as a shampoo in the treatment of experimental pityrosporosis in guinea pigs. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1990, 22, 993–998, doi:10.1016/0190-9622(90)70140-D.

- Koga, H.; Munechika, Y.; Matsumoto, H.; Nanjoh, Y.; Harada, K.; Makimura, K.; Tsuboi, R. Guinea pig seborrheic dermatitis model of Malassezia restricta and the utility of luliconazole. Med. Mycol. 2019, 00, 1–7, doi:10.1093/mmy/myz128.

- Uchida, Y.; Mizutani, M.; Kubo, T.; Nakade, T.; Otomo, K. Otitis External Induced with Malassezia pachydermatis in Dogs and the Efficacy of Pimaricin. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 1992, 54, 611–614, doi:10.1292/jvms.54.611.

- Rosenberg, E.W.; Belew, P.; Bale, G. Effect of topical applications of heavy suspensions of killed malassezia ovalis on rabbit skin. Mycopathologia 1980, 72, 147–154, doi:10.1007/BF00572657.

- Faergemann, J. Experimental tinea versicolor in rabbits and humans with Pityrosporum orbiculare. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1979, 72, 326—329, doi:10.1111/1523-1747.ep12531766.

- Faergemann, J.; Fredriksson, T. Experimental Infections in Rabbits and Humans with Pityrosporum orbiculare and P. ovale. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1981, 77, 314–318, doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12482488.

- Groisser, D.; Bottone, E.J.; Lebwohl, M. Association of Pityrosporum orbiculare (Malassezia furfur) with seborrheic dermatitis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1989, 20, 770-773, doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(89)70088-8.

- Conant, M.A. The AIDS epidemic. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1994, 31, S47–S50, doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(08)81267-4.

- Oble, D.A.; Collett, E.; Hsieh, M.; Ambjrn, M.; Law, J.; Dutz, J.; Teh, H.-S. A Novel T Cell Receptor Transgenic Animal Model of Seborrheic Dermatitis-Like Skin Disease. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2005, 124, 151–159, doi:10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23565.x.

- Yamasaki, S.; Matsumoto, M.; Takeuchi, O.; Matsuzawa, T.; Ishikawa, E.; Sakuma, M.; Tateno, H.; Uno, J.; Hirabayashi, J.; Mikami, Y.; et al. C-type lectin Mincle is an activating receptor for pathogenic fungus, Malassezia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009, 106, 1897-1902, doi:10.1073/pnas.0805177106.

- Schlemmer, K.B.; Jesus, F.P.K.; Loreto, É.S.; Tondolo, J.S.M.; Ledur, P.C.; Dallabrida, A.; da Silva, T.M.; Kommers, G.D.; Alves, S.H.; Santurio, J.M. An experimental murine model of otitis and dermatitis caused by Malassezia pachydermatis. Mycoses 2018, 61, 954–958, doi:10.1111/myc.12839.

- Rosowski, E.E.; Knox, B.P.; Archambault, L.S.; Huttenlocher, A.; Keller, N.P.; Wheeler, R.T.; Davis, J.M. The zebrafish as a model host for invasive fungal infections. J. Fungi 2018, 4, 1–26, doi:10.3390/jof4040136.

- Doke, S.K.; Dhawale, S.C. Alternatives to animal testing: A review. Saudi Pharm. J. 2015, 23, 223–229, doi:10.1016/j.jsps.2013.11.002.

- Mylonakis, E.; Casadevall, A.; Ausubel, F.M. Exploiting amoeboid and non-vertebrate animal model systems to study the virulence of human pathogenic fungi. PLoS Pathog. 2007, 3, e101, doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0030101.

- Novohradská, S.; Ferling, I.; Hillmann, F. Exploring virulence determinants of filamentous fungal pathogens through interactions with soil amoebae. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, doi.10.3389/fcimb.2017.00497

- Johnson, C.H.; Ayyadevara, S.; McEwen, J.E.; Shmookler Reis, R.J. Histoplasma capsulatum and Caenorhabditis elegans: A simple nematode model for an innate immune response to fungal infection. Med. Mycol. 2009, 47, 808–813, doi:10.3109/13693780802660532.

- Mylonakis, E.; Ausubel, F.M.; Perfect, J.R.; Heitman, J.; Calderwood, S.B. Killing of Caenorhabditis elegans by Cryptococcus neoformans as a model of yeast pathogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2002, 99, 15675–15680, doi:10.1073/pnas.232568599.

- Scorzoni, L.; de Lucas, M.P.; Singulani, J. de L.; de Oliveira, H.C.; Assato, P.A.; Fusco-Almeida, A.M.; Mendes-Giannini, M.J.S. Evaluation of Caenorhabditis elegans as a host model for Paracoccidioides brasiliensis and Paracoccidioides lutzii. Pathog. Dis. 2018, 76, 1-6, doi:10.1093/femspd/fty004.

- Merkel, S.; Heidrich, D.; Danilevicz, C.K.; Scroferneker, M.L.; Zanette, R.A. Drosophila melanogaster as a model for the study of Malassezia pachydermatis infections. Vet. Microbiol. 2018, 224, 31–33, doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2018.08.021.

- Alarco, A.-M.; Marcil, A.; Chen, J.; Suter, B.; Thomas, D.; Whiteway, M. Immune-Deficient Drosophila melanogaster : A Model for the Innate Immune Response to Human Fungal Pathogens . J. Immunol. 2004, 172, 5622–5628, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.172.9.5622.

- Glittenberg, M.T.; Silas, S.; MacCallum, D.M.; Gow, N.A.R.; Ligoxygakis, P. Wild-type Drosophila melanogaster as an alternative model system for investigating the pathogenicity of Candida albicans. DMM Dis. Model. Mech. 2011, 4, 504–514, doi:10.1242/dmm.006619.

- de Souza, P.C.; Caloni, C.C.; Wilson, D.; Almeida, R.S. An invertebrate host to study fungal infections, mycotoxins and antifungal drugs: Tenebrio molitor. J. Fungi 2018, 4, 1–12, doi:10.3390/jof4040125.

- Matsumoto, Y.; Sekimizu, K. Silkworm as an experimental animal for research on fungal infections. Microbiol. Immunol. 2019, 63, 41–50, doi:10.1111/1348-0421.12668.

- Trevijano-Contador, N.; Zaragoza, O. Immune response of Galleria mellonella against human fungal pathogens. J. Fungi 2019, 5, 1–13, doi:10.3390/jof5010003.

- Pereira, T.; de Barros, P.; Fugisaki, L.; Rossoni, R.; Ribeiro, F.; de Menezes, R.; Junqueira, J.; Scorzoni, L. Recent advances in the use of Galleria mellonella model to study immune responses against human pathogens. J. Fungi 2018, 4, 1–19, doi:10.3390/jof4040128.

- Singkum, P.; Suwanmanee, S.; Pumeesat, P.; Luplertlop, N. A powerful in vivo alternative model in scientific research: Galleria mellonella. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2019, 66, 31–55, doi:10.1556/030.66.2019.001.

- Jemel, S.; Guillot, J.; Kallel, K.; Botterel, F.; Dannaoui, E. Galleria mellonella for the evaluation of antifungal efficacy against medically important fungi, a narrative review. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1–20, doi:10.3390/microorganisms8030390.

- Amorim-Vaz, S.; Delarze, E.; Ischer, F.; Sanglard, D.; Coste, A.T. Examining the virulence of Candida albicans transcription factor mutants using Galleria mellonella and mouse infection models. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1–14, doi:10.3389/fmicb.2015.00367.

- Cotter, G.; Doyle, S.; Kavanagh, K. Development of an insect model for the in vivo pathogenicity testing of yeasts. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2000, 27, 163–169, doi:10.1111/j.1574-695X.2000.tb01427.x.

- Sheehan, G.; Tully, L.; Kavanagh, K.A. Candida albicans increases the pathogenicity of Staphylococcus aureus during polymicrobial infection of Galleria mellonella larvae. Microbiology 2020, 166, 375–385, doi:10.1099/mic.0.000892.

- Sheehan, G.; Kavanagh, K. Analysis of the early cellular and humoral responses of Galleria mellonella larvae to infection by Candida albicans. Virulence 2018, 9, 163–172, doi.10.1080/21505594.2017.1370174.

- Brennan, M.; Thomas, D.Y.; Whiteway, M.; Kavanagh, K. Correlation between virulence of Candida albicans mutants in mice and Galleria mellonella larvae . FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2002, 34, 153–157, doi:10.1111/j.1574-695X.2002.tb00617.x.

- Slater, J.L.; Gregson, L.; Denning, D.W.; Warn, P.A. Pathogenicity of Aspergillus fumigatus mutants assessed in Galleria mellonella matches that in mice. Med. Mycol. 2011, 49, S107–S113, doi.10.3109/13693786.2010.523852.

- Brilhante, R.S.N.; Rocha, M.G. da; Guedes, G.M. de M.; Oliveira, J.S. de; Araújo, G. dos S.; España, J.D.A.; Sales, J.A.; Aguiar, L. de; Paiva, M. de A.N.; Cordeiro, R. de A.; et al. Malassezia pachydermatis from animals: Planktonic and biofilm antifungal susceptibility and its virulence arsenal. Vet. Microbiol. 2018, 220, 47–52, doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2018.05.003.

- Silva Rabelo, A.P..; Valério, A..; Viana, R.O.; Ricoy, A.C.D.S.; Johann, S.; Alves, V.D.S. Caenorhabditis Elegans and Tenebrio Molitor - New Tools to Investigate Malassezia Species. Preprints 2018, 2018100001, doi:10.20944/preprints201810.0001.v1.

- Singulani, J.L.; Scorzoni, L.; de Oliveira, H.C.; Marcos, C.M.; Assato, P.A.; Fusco-Almeida, A.M.; Mendes-Giannini, M.J.S. Applications of invertebrate animal models to dimorphic fungal infections. J. Fungi 2018, 4, 1–19, doi:10.3390/jof4040118.

- Fuchs, B.B.; O’Brien, E.; El Khoury, J.B.; Mylonakis, E. Methods for using Galleria mellonella as a model host to study fungal pathogenesis. Virulence 2010, 1, 475–482, doi:10.4161/viru.1.6.12985.

- T Thomaz, L.; García-Rodas, R.; Guimarães, A.J.; Taborda, C.P.; Zaragoza, O.; Nosanchuk, J.D. Galleria mellonella as a model host to study Paracoccidioides Lutzii and Histoplasma Capsulatum. Virulence 2013, 4, 139–146, doi:10.4161/viru.23047.

- Coleman, J.J.; Muhammed, M.; Kasperkovitz, P. V.; Vyas, J.M.; Mylonakis, E. Fusarium pathogenesis investigated using Galleria mellonella as a heterologous host. Fungal Biol. 2011, 115, 1279–1289, doi:10.1016/j.funbio.2011.09.005.

- Kloezen, W.; van Helvert-van Poppel, M.; Fahal, A.H.; van de Sande, W.W.J. A Madurella mycetomatis grain model in Galleria mellonella larvae. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, 1–14, doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0003926.

- Benaducci, T.; Sardi, J. de C.O.; Lourencetti, N.M.S.; Scorzoni, L.; Gullo, F.P.; Rossi, S.A.; Derissi, J.B.; de Azevedo Prata, M.C.; Fusco-Almeida, A.M.; Mendes-Giannini, M.J.S. Virulence of Cryptococcus sp. biofilms in vitro and in vivo using Galleria mellonella as an alternative model. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1–10, doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.00290.

- Scorzoni, L.; de Lucas, M.P.; Mesa-Arango, A.C.; Fusco-Almeida, A.M.; Lozano, E.; Cuenca-Estrella, M.; Mendes-Giannini, M.J.; Zaragoza, O. Antifungal Efficacy during Candida krusei Infection in Non-Conventional Models Correlates with the Yeast In Vitro Susceptibility Profile. PLoS One 2013, 8, 1–13, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0060047.

- Sheehan, G.; Kavanagh, K. Proteomic analysis of the responses of Candida albicans during infection of Galleria mellonella larvae. J. Fungi 2019, 5, 1–12, doi:10.3390/jof5010007.

- Mowlds, P.; Coates, C.; Renwick, J.; Kavanagh, K. Dose-dependent cellular and humoral responses in Galleria mellonella larvae following β-glucan inoculation. Microbes Infect. 2010, 12, 146–153, doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2009.11.004.

- Fallon, J.P.; Troy, N.; Kavanagh, K. Pre-exposure of Galleria mellonella larvae to different doses of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia causes differential activation of cellular and humoral immune responses. Virulence 2011, 2, 413–421, doi:10.4161/viru.2.5.17811.

- Bergin, D.; Murphy, L.; Keenan, J.; Clynes, M.; Kavanagh, K. Pre-exposure to yeast protects larvae of Galleria mellonella from a subsequent lethal infection by Candida albicans and is mediated by the increased expression of antimicrobial peptides. Microbes Infect. 2006, 8, 2105–2112, doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2006.03.005.

- Mesa-Arango, A.C.; Forastiero, A.; Bernal-Martínez, L.; Cuenca-Estrella, M.; Mellado, E.; Zaragoza, O. The non-mammalian host Galleria mellonella can be used to study the virulence of the fungal pathogen Candida tropicalis and the efficacy of antifungal drugs during infection by this pathogenic yeast. Med. Mycol. 2013, 51, 461–472, doi:10.3109/13693786.2012.737031.

- de Lacorte Singulani, J.; Scorzoni, L.; de Paula e Silva, A.C.A.; Fusco-Almeida, A.M.; Mendes-Giannini, M.J.S. Evaluation of the efficacy of antifungal drugs against Paracoccidioides brasiliensis and Paracoccidioides lutzii in a Galleria mellonella model. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2016, 48, 292–297, doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2016.05.012.

- Astvad, K.M.T.; Meletiadis, J.; Whalley, S.; Arendrup, M.C. Fluconazole pharmacokinetics in Galleria mellonella larvae and performance evaluation of a bioassay compared to liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry for hemolymph specimens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, 1–8, doi:10.1128/AAC.00895-17.

- Vogel, H.; Altincicek, B.; Glöckner, G.; Vilcinskas, A. A comprehensive transcriptome and immune-gene repertoire of the lepidopteran model host Galleria mellonella. BMC Genomics 2011, 12, 1–19, doi:10.1186/1471-2164-12-308.

- Mukherjee, K.; Vilcinskas, A. Development and immunity-related microRNAs of the lepidopteran model host Galleria mellonella. BMC Genomics 2014, 15, 1–12, doi:10.1186/1471-2164-15-705.

- Torres, M.; Pinzón, E.N.; Rey, F.M.; Martinez, H.; Parra Giraldo, C.M.; Celis Ramírez, A.M. Galleria mellonella as a Novelty in vivo Model of Host-Pathogen Interaction for Malassezia furfur CBS 1878 and Malassezia pachydermatis CBS 1879. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 1–13, doi:10.3389/fcimb.2020.00199.