| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SANTOSH REDDY ALLURI | + 1508 word(s) | 1508 | 2020-09-09 17:20:07 | | | |

| 2 | Felix Wu | -25 word(s) | 1483 | 2020-10-27 04:29:58 | | |

Video Upload Options

Epinephrine (E) and norepinephrine (NE) play diverse roles in our body’s physiology. In addition to their role in the peripheral nervous system (PNS), E/NE systems including their receptors are critical to the central nervous system (CNS) and to mental health.

1. Introduction

Positron emission tomography (PET) is a noninvasive and highly sensitive in vivo imaging technique that uses small amounts of radiotracers to detect the concentration of relevant biomarkers in tissues such as receptors, enzymes, and transporters. These radiotracers can be used to characterize neurochemical changes in neuropsychiatric diseases and also to measure drug pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics directly in the human body including the brain [1][2]. PET technology requires positron-emitting radioisotopes, a radiotracer synthesis unit, a PET scanner, and data acquisition components. Among the PET isotopes, cyclotron produced carbon-11 (C-11, t1/2 = 20.34 min), nitrogen-13 (N-13, t1/2 = 9.96 min), and fluorine-18 (F-18, t1/2 = 109.77 min) are frequently used for PET-neuroimaging. PET imaging is particularly valuable to characterize investigational drugs and their target proteins, providing a valuable tool for clinical neuroscience [3].

PET radiotracers for the central nervous system (CNS) should have proper pharmacokinetic profile in the brain and to achieve this property, they were designed to meet five molecular properties: a) molecular weight <500 kDa, b) Log D7.4 between ~1 to 3 (lipophilicity factor), c) number of hydrogen bond donors <5, d) number of hydrogen bond acceptors <10, and e) topological polar surface area <90 Å2.

2. α1-AR PET Radiotracers

Three highly homologous subunits of α-1 ARs, α1A, α1B, and α1D, have been shown to have different amino acid sequence, pharmacological properties, and tissue distributions [4][5][6]. A detailed review of α1-AR pharmacology is given by Michael and Perez [4]. Binding of NE/E to any of the α1-AR subtypes is stimulatory and activates Gq/11-signalling pathway, which involves phospholipase C activation, generation of secondary messengers, inositol triphosphate and diacyl glycerol and intracellular calcium mobilization. In PNS, as well as in the brain’s vascular system it results in smooth muscle contraction and vasoconstriction. While the signaling effects of α1-ARs in the cardiovascular system are well studied [7][8], the role of α1-ARs in CNS is complex and not completely understood. The Bmax values of α-1 ARs were measured from saturation assays using [3H]prazosin (a selective α-1 blocker) with tissue homogenates from rats and the observed binding capacities (fmol/mg tissue) of prazosin in cortex, hippocampus, and cerebellum were 14.49 ± 0.38, 11.03 ± 0.39, and 7.72 ± 0.11, respectively [9][10]. The α1-ARs are postsynaptic receptors and can also modulate release of NE. In the human brain, α1-AR subtypes are localized in amygdala, cerebellum, thalamus, hippocampus, and to some extent in striatum [11][12][13].

The anti-depressant effects of noradrenergic enhancing drugs as well as their effects on anxiety and stress reactivity points to their relevance of α1A, α1D to these behaviors [14][15][16]. Furthermore, α1A-ARs regulate GABAergic and NMDAergic neurons [11]. A decrease in α1A-AR mRNA expression was observed in prefrontal cortex of subjects with dementia [17][18]. The α1B-ARs has also been shown to be crucial to brain function and disease [19]. For example, α1B-knockout (KO) mice study revealed that α1B-AR modulates behavior, showing increased reaction to novel situations [20][21]. In addition, the locomotor and rewarding effects of psychostimulants and opiates were decreased in α1B-KO mice, highlighting their role in the pharmacological effects of these drugs [20]. On the other hand, studies using the α1B-overexpression model suggest their involvement in neurodegenerative diseases [22].

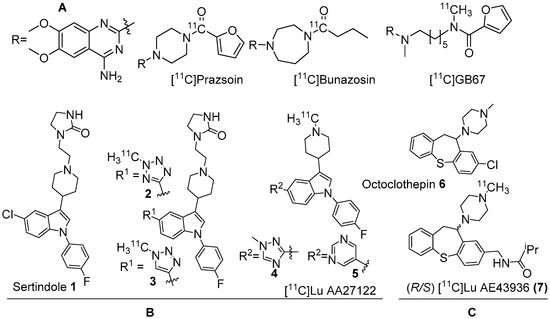

Several α1-AR agonists and antagonists (α1-blockers) are available in the market as drugs to treat various heart and brain disorders [23][24]. Pharmacology of most of these drugs is complicated by the fact that they have strong affinities for other receptor systems, such as serotonin and dopamine receptors. The need to develop α1-AR selective/α1-AR subtype specific drugs is demanding. Undoubtedly, PET radiotracers selective for α1-AR are valuable to assess α1-ARs contribution to brain function and disease. In the late 1980s, prazosin, used for the treatment of hypertension, was labelled with carbon-11 to image α1-ARs with PET [25]. Following this, [11C]prazosin analogous, [11C]bunazosin and [11C]GB67 (Figure 1A) were developed as PET radiotracers to image α1-ARs in the cardiovascular system [25][26]. These tracers were shown to have limited BBB permeability and were deemed to be not suitable for PET-neuroimaging. Efforts to develop PET radiotracers to image α1-ARs in the CNS was mainly based on antipsychotic drugs such as clozapine, sertindole, olanzapine, and risperidone that have mixed binding affinities for D2, 5HT2A receptors and α1-ARs in the nanomolar range. Their affinity for α1-ARs has been shown to contribute to antipsychotic efficacy uncovering their role in psychoses [27][28].

Figure 1. (A) Earlier PET radiotracers, [11C]Prazosin, [11C]Bunazosin, and [11C]GB67 for cardiac α1-AR imaging. (B) Antagonist PET radiotracers based on sertindole. (C) Antagonist PET radiotracers based on octoclothepin for brain α1-AR imaging.

Two C-11 labelled analogs of the atypical antipsychotic drug sertindole were first reported by Balle et al. in the early 2000s (Figure 1B) [29][30]. Several other analogs with good affinities (Ki < 10 nM) for α1-ARs were subsequently reported by the same group. Two analogs, in which chlorine in sertindole (1) is replaced by a 2-methyl-tetrazol-5-yl (2) and a 1-methyl-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl (3), were labelled with C-11 [29][30]. The in vitro affinities (Ki) of 1, 2 and 3 for α1-ARs are 1.4, 1.8 and 9.5 nM, respectively. Both [11C]2 and [11C]3 were prepared using 11C-methylation with [11C]methyl triflate from their corresponding N-desmethyl precursors. The molar activity of [11C]2 and [11C]3 was reported at 70 GBq/μmol and 15 GBq/μmol, respectively. Their brain distribution examined with PET in Cynomolgus monkeys showed that brain uptake of [11C]2 and [11C]3 was slow and low, with [11C]3 showing somewhat higher brain uptake than [11C]2. Their brain distribution was homogenous and specific binding to α1-ARs could not be demonstrated. It was also concluded that these two radiotracers were not suitable to image α1-ARs in brain owing to rapid metabolism, substantial distribution to other organs, and substrates for active efflux mechanism.

3. β-ARs and Nonselective PET Radiotracers

β-ARs are associated with Gs-heterotrimeric G-protein and mediate intracellular signaling through adenyl cyclase activation and cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) production. β-ARs

are classified into β1, β2, and β3 subtypes, in which, the former two have been much more explored [31][32]. Quite a lot of selective and nonselective β-AR agonists and antagonists (blockers) are available as drugs in the market to treat various cardiac and pulmonary disorders. In the brain, β-ARs are localized in the frontal cortex, striatum, thalamus, putamen, amygdala, cerebellum and hippocampus [33]. The density of β-ARs in brain is sensitive to brain pathophysiology. Notably, the density of β-ARs decrease with age [34]. Light microscopic autoradiography using [3H]dihydroaloprenolol (a selective β-blocker) with rat brain sections has shown a wide distribution of β-ARs in forebrain and cerebellum regions (Bmax = 23 fmol/mg tissue) [35]. Similarly, Bmax value of 18 fmol/mg protein was reported in pre-frontal cortex of subjects with Parkinson’s disease [33][36]. By altering the Ca2+ levels through N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors in hippocampus, β-ARs modulate synaptic plasticity, including that needed for memory [37][38]. The blockade of β-ARs is associated with a small increased risk for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease [39][40]. In addition, abnormal function and densities of β-ARs have been reported in mood disorders and schizophrenia [41][42][43].

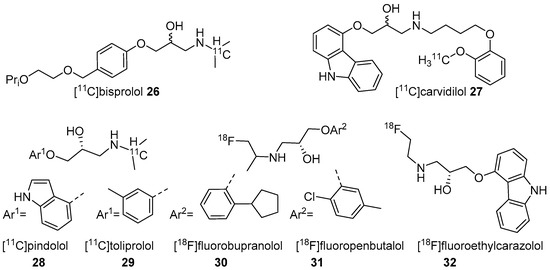

Several radioligands, mostly based on β-blockers, were validated for imaging of β-ARs in the heart [44]. The majority of β-blockers possess a hydroxyl propylamine moiety in their structures that is vital for binding to β-ARs and this moiety was maintained in most of these radioligands. PET radiotracers have succeeded in imaging and quantifying myocardial and pulmonary β-ARs in human [45][46], whereas, PET radiotracers for cerebral β-ARs have been more challenging. The clinical PET radiotracers for cardiac β-ARs have negative Log P values (<−2), which is not suitable for imaging the brain. Several lipophilic and high to moderate affinity β-AR nonselective antagonists were explored as PET radiotracers to image β-ARs in the brain.

In 2001, Fazio’s group described two isomers (R/S) of C-11 labelled bisprolol (β1 Ki 1.6 nM, β2 Ki 100 nM and Log P7.4 = −0.2) (26, Figure 2) to image β1-ARs in the brain [47]. The radiosynthesis of 26 was accomplished via reductive amination using [11C]acetone and desisopropyl bisprolol precursor with 129.5 ± 37 GBq/μmol molar activity at the EOS. They observed little specific uptake of 26 in β1-AR rich regions in the rat’s brain and also high nonspecific uptake in the pituitary (1.8 ± 0.3 ID at 30 min), a region with high β2-ARs levels. No further studies were reported using 26 to image β-ARs.

Figure 2. Radiotracers based on various β-AR blockers.

The five radiotracers had strong affinities (subnanomolar Kd) for β1 and β2-ARs. Although these radiotracers had sufficient affinity and lipophilicity for in vivo imaging, none showed good brain uptake. This group also evaluated S-[18F]fluoroethylcarazolol (32, β1 Ki = 0.5 nM, β2 Ki = 0.4 nM and Log P7.4 = 1.94) for in vivo imaging of β-ARs in rat brain [119]. The radiotracer 32 (Figure 2) was prepared via an epoxide ring-opening using [18F]fluoroethylamine and the corresponding epoxide with >10 GBq/μmol molar activity. The radiotracer accumulated in brain with uptake reflecting cerebral β-ARs binding. However, no further PET imaging studies were reported using 32 probably because of its analogous nature to 23 which was shown to be positive Ames test [48][49].

References

- Scott, J.A. Positron Emission Tomography: Basic Science and Clinical Practice. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2004, 182, 418.

- Shukla, A.; Kumar, U. Positron emission tomography: An overview. J. Med. Phys. 2006, 31, 13–21.

- Stuart P. McCluskey; Christophe Plisson; Eugenii A. Rabiner; Oliver Howes; Advances in CNS PET: the state-of-the-art for new imaging targets for pathophysiology and drug development. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 2019, 47, 451-489, 10.1007/s00259-019-04488-0.

- Piascik, M.T.; Perez, D.M. α1-Adrenergic receptors: New insights and directions. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001, 298, 403–410.

- Graham, R.M.; Perez, D.M.; Hwa, J.; Piascik, M.T. α1 -Adrenergic Receptor Subtypes. Circ. Res. 1996, 78, 737–749.

- Chen, Z.J.; Minneman, K.P. Recent progress in α1-adrenergic receptor research. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2005, 26, 1281–1287.

- O’Connell, T.D.; Jensen, B.C.; Baker, A.J.; Simpson, P.C. Cardiac alpha1-adrenergic receptors: Novel aspects of expression, signaling mechanisms, physiologic function, and clinical importance. Pharmacol. Rev. 2014, 66, 308–333.

- Jensen, B.C.; O’Connell, T.D.; Simpson, P.C. Alpha-1-adrenergic receptors in heart failure: The adaptive arm of the cardiac response to chronic catecholamine stimulation. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2014, 63, 291–301.

- T. A. Reader; Louise Grondin; Alpha-1 and alpha-2 adrenoceptor binding in cerebral cortex: Competition studies with [3H]prazosin and [3H]idazoxan. Journal of Neural Transmission 1987, 68, 79-95, 10.1007/bf01244641.

- A L Morrow; I Creese; Characterization of alpha 1-adrenergic receptor subtypes in rat brain: a reevaluation of [3H]WB4104 and [3H]prazosin binding.. Molecular Pharmacology 1986, 29, 321-30.

- Heidi E.W Day; Serge Campeau; Stanley J Watson; Huda Akil; Distribution of α1a-, α1b- and α1d-adrenergic receptor mRNA in the rat brain and spinal cord. Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy 1997, 13, 115-139, 10.1016/s0891-0618(97)00042-2.

- Leslie, A. Characterization of a1-Adrenergic Receptor Subtypes in Rat Brain: A Reevaluation of [3H] WB41 04 and [3H] Prazosin Binding. Pharmacol. Exet. Am. Chem. Sciety Pharmacol. Experiemntal Ther. 1986, 29, 321–330.

- Carmen Romero-Grimaldi; Bernardo Moreno-López; Carmen Estrada; Age-dependent effect of nitric oxide on subventricular zone and olfactory bulb neural precursor proliferation. The Journal of Comparative Neurology 2007, 506, 339-346, 10.1002/cne.21556.

- Serge Campeau; Tara J. Nyhuis; Elisabeth M. Kryskow; Cher V. Masini; Jessica A. Babb; Sarah K. Sasse; Benjamin N. Greenwood; Monika Fleshner; Heidi E.W. Day; Stress rapidly increases alpha 1d adrenergic receptor mRNA in the rat dentate gyrus. Brain Research 2010, 1323, 109-118, 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.01.084.

- Van A. Doze; Evelyn M. Handel; Kelly A. Jensen; Belle Darsie; Elizabeth J. Luger; James R. Haselton; Jeffery N. Talbot; Boyd R. Rorabaugh; α1A- and α1B-adrenergic receptors differentially modulate antidepressant-like behavior in the mouse. Brain Research 2009, 1285, 148-157, 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.06.035.

- A Sadalge; L Coughlin; H Fu; B Wang; O Valladares; R Valentino; J A Blendy; α1d Adrenoceptor signaling is required for stimulus induced locomotor activity. Molecular Psychiatry 2003, 8, 664-672, 10.1038/sj.mp.4001351.

- Szot, P.; White, S.S.; Greenup, J.L.; Leverenz, J.B.; Peskind, E.R.; Raskind, M.A. Changes in Adrenoreceptors in The Prefrontal Cortex Of Subjects With Dementia: Evidence Of Compensatory Changes. Neuroscience 2007, 146, 471–480.

- Perez, D.M.; Doze, V.A. Cardiac and neuroprotection regulated by alpha1-AR subtypes. J. Recept Signal. Transduct Res. 2011, 31, 98–110.

- Melanie Philipp; Lutz Hein; Adrenergic receptor knockout mice: distinct functions of 9 receptor subtypes. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2004, 101, 65-74, 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2003.10.004.

- Candice Drouin; Laurent Darracq; Fabrice Trovero; Gérard Blanc; Jacques Glowinski; Susanna Cotecchia; Jean-Pol Tassin; α1b-Adrenergic Receptors Control Locomotor and Rewarding Effects of Psychostimulants and Opiates. Journal of Neuroscience 2002, 22, 2873-2884, 10.1523/jneurosci.22-07-02873.2002.

- Matthieu Spreng; Susanna Cotecchia; Françoise Schenk; A Behavioral Study of Alpha-1b Adrenergic Receptor Knockout Mice: Increased Reaction to Novelty and Selectively Reduced Learning Capacities. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory 2001, 75, 214-229, 10.1006/nlme.2000.3965.

- Michael J. Zuscik; Scott Sands; Sean A. Ross; David J. J. Waugh; Robert J. Gaivin; David Morilak; Dianne M. Perez; Overexpression of the α1B-adrenergic receptor causes apoptotic neurodegeneration: Multiple system atrophy. Nature Medicine 2000, 6, 1388-1394, 10.1038/82207.

- Sica, D. Alpha-1 adrenergic Blockers: Current Usage Considerations. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2005, 7, 757–762.

- Miriam, H.; Hein, L. α1-Adrenozeptor-Antagonisten. Bei BPS und Hypertonie. Pharm. unserer Zeit 2008, 37, 290–295.

- V.W Pike; M.P Law; S Osman; R.J Davenport; O Rimoldi; D Giardinà; P.G Camici; Selection, design and evaluation of new radioligands for PET studies of cardiac adrenoceptors. Pharmaceutica Acta Helvetiae 2000, 74, 191-200, 10.1016/s0031-6865(99)00032-1.

- Marilyn P. Law; Safiye Osman; Victor W. Pike; Raymond J. Davenport; Vincent J. Cunningham; Ornella Rimoldi; Christopher G. Rhodes; Dario Giardinà; Paolo G. Camici; Evaluation of [11C]GB67, a novel radioligand for imaging myocardial α1-adrenoceptors with positron emission tomography. European Journal of Pediatrics 2000, 27, 7-17, 10.1007/pl00006665.

- Nyberg, S.; Eriksson, B.; Oxenstierna, G.; Halldin, C.; Farde, L. Suggested minimal effective dose of risperidone based on PET-measured D2 and 5-HT(2A) receptor occupancy in schizophrenic patients. Am. J. Psychiatry 1999, 156, 869–875.

- Nyberg, S.; Olsson, H.; Nilsson, U.; Maehlum, E.; Halldin, C.; Farde, L. Low striatal and extra-striatal D2 receptor occupancy during treatment with the atypical antipsychotic sertindole. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2002, 162, 37–41.

- Balle, T.; Perregaard, J.; Ramirez, M.T.; Larsen, A.K.; Søby, K.K.; Liljefors, T.; Andersen, K. Synthesis and structure-affinity relationship investigations of 5-heteroaryl-substituted analogues of the antipsychotic sertindole. A new class of highly selective α1 adrenoceptor antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 2003, 46, 265–283.

- Balle, T.; Halldin, C.; Andersen, L.; Alifrangis, L.H.; Badolo, L.; Jensen, K.G.; Chou, Y.W.; Andersen, K.; Perregaard, J.; Farde, L. New α1-adrenoceptor antagonists derived from the antipsychotic sertindole—Carbon-11 labelling and pet examination of brain uptake in the cynomolgus monkey. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2004, 31, 327–336.

- Gerd Wallukat; The β-Adrenergic Receptors. Herz 2002, 27, 683-690, 10.1007/s00059-002-2434-z.

- S. Blake Wachter; Edward M. Gilbert; Beta-Adrenergic Receptors, from Their Discovery and Characterization through Their Manipulation to Beneficial Clinical Application. Cardiology 2012, 122, 104-112, 10.1159/000339271.

- Aren Van Waarde; Willem Vaalburg; Petra Doze; Fokko J Bosker; Philip H Elsinga; PET Imaging of Beta-Adrenoceptors in Human Brain: A Realistic Goal or a Mirage?. Current Pharmaceutical Design 2004, 10, 1519-1536, 10.2174/1381612043384754.

- Philip J. Sscarpace; Itamar B. Abrass; Alpha- and beta-adrenergic receptor function in the brain during senescence. Neurobiology of Aging 1988, 9, 53-58, 10.1016/s0197-4580(88)80021-6.

- J Palacios; M J Kuhar; Beta adrenergic receptor localization in rat brain by light microscopic autoradiography. Neurochemistry International 1982, 4, 473-490, 10.1016/0197-0186(82)90036-5.

- Roland Cash; Merle Ruberg; Rita Raisman; Yves Agid; Adrenergic receptors in Parkinson's disease. Brain Research 1984, 322, 269-275, 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90117-3.

- O’Dell, T.J.; Connor, S.A.; Guglietta, R.; Nguyen, P.V. β-Adrenergic receptor signaling and modulation of long-term potentiation in the mammalian hippocampus. Learn. Mem. 2015, 22, 461–471.

- Gelinas, J.; Nguyen, P. Neuromodulation of Hippocampal Synaptic Plasticity, Learning, and Memory by Noradrenaline. Cent. Nerv. Syst. Agents Med. Chem. 2008, 7, 17–33.

- Khanh Vinh Quốc Lương; Lan Thi Hoàng Nguyễn; The Role of Beta-Adrenergic Receptor Blockers in Alzheimer’s Disease. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease & Other Dementias® 2013, 28, 427-439, 10.1177/1533317513488924.

- Franziska Hopfner; Günter U Höglinger; Gregor Kuhlenbäumer; Anton Pottegård; Mette Wod; Kaare Christensen; Caroline M Tanner; Günther Deuschl; β-adrenoreceptors and the risk of Parkinson's disease. The Lancet Neurology 2020, 19, 247-254, 10.1016/s1474-4422(19)30400-4.

- Subhash C Pandey; Xinguo Ren; Jacqeuline Sagen; Ghanshyam N Pandey; β-Adrenergic receptor subtypes in stress-induced behavioral depression. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior 1995, 51, 339-344, 10.1016/0091-3057(94)00392-v.

- Jeffrey N. Joyce; Nedra Lexow; Soo Jin Kim; Roman Artymyshyn; Shari Senzon; David Lawerence; Manuel F. Cassanova; Joel E. Kleinman; Edward D. Bird; Andrew Winokur; et al. Distribution of beta-adrenergic receptor subtypes in human post-mortem brain: Alterations in limbic regions of schizophrenics. Synapse 1992, 10, 228-246, 10.1002/syn.890100306.

- Violetta Klimek; Grazyna Rajkowska; Stephen N Luker; Ginny Dilley; Herbert Y Meltzer; James C. Overholser; Craig A. Stockmeier; Gregory A. Ordway; Brain Noradrenergic Receptors in Major Depression and Schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology 1999, 21, 69-81, 10.1016/s0893-133x(98)00134-1.

- Xinyu Chen; Rudolf A. Werner; Mehrbod S. Javadi; Yoshifumi Maya; Michael Decker; Constantin Lapa; Ken Herrmann; Takahiro Higuchi; Radionuclide Imaging of Neurohormonal System of the Heart. Theranostics 2015, 5, 545-558, 10.7150/thno.10900.

- Ueki, J.; Rhodes, C.G.; Hughes, J.M.; De Silva, R.; Lefroy, D.C.; Ind, P.W.; Qing, F.; Brady, F.; Luthra, S.K.; Steel, C.J. In vivo quantification of pulmonary B-adrenoceptor density in humans with (S)-[11C]CGP-12177 and PET. Am. Physiol. Soc. 1993, 75, 559–565.

- Elsinga, P.H.; Doze, P.; Van Waarde, A.; Pieterman, R.M.; Blanksma, P.K.; Willemsen, A.T.M.; Vaalburg, W. Imaging of β-adrenoceptors in the human thorax using (S)-[11C]CGP12388 and positron emission tomography. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2001, 433, 173–176.

- Dmitri V. Soloviev; Mario Matarrese; Rosa Maria Moresco; S. Todde; Thomas A. Bonasera; Francesco Sudati; Pasquale Simonelli; Fulvio Magni; Diego Colombo; Assunta Carpinelli; et al.Marzia Galli KienleFerruccio Fazio Asymmetric synthesis and preliminary evaluation of (R)- and (S)-[11C]bisoprolol, a putative β1-selective adrenoceptor radioligand. Neurochemistry International 2001, 38, 169-180, 10.1016/s0197-0186(00)00049-8.

- P Doze; P.H Elsinga; E.F.J De Vries; A Van Waarde; W Vaalburg; Mutagenic activity of a fluorinated analog of the beta-adrenoceptor ligand carazolol in the Ames test. Nuclear Medicine and Biology 2000, 27, 315-319, 10.1016/s0969-8051(00)00087-1.

- Aren Van Waarde; Janine Doorduin; Johan R. De Jong; Rudi A. Dierckx; Philip H. Elsinga; Synthesis and preliminary evaluation of (S)-[11C]-exaprolol, a novel β-adrenoceptor ligand for PET. Neurochemistry International 2008, 52, 729-733, 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.09.009.