Health policies are regarded as a governance mechanism crucial for reducing health inequity and improving overall health outcomes. However, the current literature in health policy largely focused on some specific health policy changes and their tangible outcomes, or on specific inequality of health policies in gender, age, racial, or socio-economic status, short of comprehensively responding to and addressing the shift from disease-centered to active-health-oriented. A comprehensive framework is proposed to identify the main elements of a well-defined active health governance and the interactions between these elements. The proposed framework is composed of four elements and three approaches that are dynamically interacted to achieve two active health outcomes.

1. Introduction

Health policies aim at improving overall health outcomes and reducing health inequalities for the entire population through individual or collective health related intervention. To tackle challenges of the time, such as increased population ageing, heavy burden of chronic diseases, growing inequalities in health, uprising pressure from health expenditures, social expectations for better health conditions

[1][2], health policies are experiencing a shift from disease-centered to active-health oriented.

It can be discerned this shift from both health policy research and health policy making that pay greater attention to those challenges in general and chronic conditions and health inequalities in particular. First, strategies that policymakers can use to tackle chronic diseases are being developed. For example, self-management support focuses on the active participation of patients in their treatment through patient education

[3], and integrated care focuses on improving linkage or coordination of services of different providers along the continuum of care

[4]. Second, policies reducing health inequalities have undergone changes from centering on individual health behaviors to emphasizing the gradient and social determinants of health

[5]. Some scholars view this policy change as a shift from “downstream” health determinants (medical care, environmental factors, and health behaviors) to “upstream” health determinants (education, income, social status, and general public policy) as the root causes of health disparities and illnesses

[6]. Moving beyond the traditional health policy orientation, the shift to active health orientation emphasizes redesign and upstream intervention within and beyond the health system for purposes of reducing health inequalities, promoting wellbeing in the context of chronic conditions and containing the rising cost of maintaining healthy population.

However, this shift from disease-centered to active-health-oriented is still far from being fully addressed in scientific debate. The current literature in health policy largely focused on specific health policy changes and their tangible outcomes, such as children, ageing, migrants, and mental health policies

[7][8][9][10] or on specific inequality of health policies in gender, age, racial, or social-economic status

[11][12], short of comprehensively responding to and addressing the shift. This is exacerbated further by a common confusion that equates health policy with health care policy. As a result, many countries have used “health policy” to denote “medical care policy,” which actually is only one variable in a nation’s health equation

[13]. Moreover, most literature emphasizes a certain single health determinant at a time when studying structural determinants of health (economic, environmental, social, and cultural) or lifestyle determinants of health, while missing a more comprehensive framework to conceptualize the relationship between determinants.

2. A Proposed Framework on Active Health Governance

The narrative review of literature not only generates significant themes that scholars have fruitfully researched on health policy but also points to some issues in the current conceptualization of health policy. We noted that articles we reviewed largely focusing on specific health policy changes and their tangible outcomes by concentrating on certain elements of a theme at a time or focusing on general inequalities of health policies, short of comprehensively responding to and addressing the shifting focus in health policy and the dynamic interactions between major themes. We also observed that most literature emphasizes a certain single health determinant at a time while missing a more comprehensive framework to conceptualize the relationship between structural determinants of health or lifestyle determinants of health.

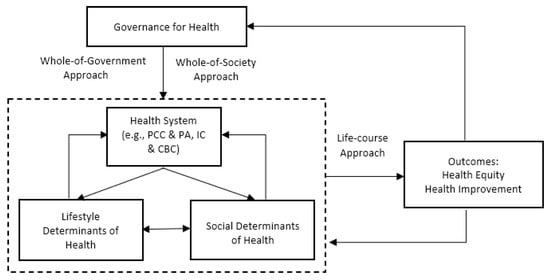

Built upon the findings of major themes in the literature, we constructed a framework on active health governance. We define active health governance as health policy and administration that adopts whole-of-government and whole-of-society approach to link all health-influencing factors and provides targeted interventions according to people’s critical life stages in order to achieve equitable and better health outcomes. This conceptual framework on active health governance that we propose is composed of four elements, three approaches, and two outcomes (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A proposed conceptual framework on active health governance.

2.1. Elements of Active Health Governance and Their Interplays

The first element of the framework is governance for health. Governance for health was defined as “the attempts of governments or other actors to steer communities, countries or groups of countries in the pursuit of health as integral to well-being through both whole-of-government and whole-of-society approaches”

[14]. The concept of governance for health can best be illustrated as “the culmination of three waves in the expansion of health policy—from intersectoral action, to healthy public policy to the health in all policies (HiAP) approach—all of which are now integrated in whole-of-government and whole-of-society approaches to health and well-being”

[14][15].

The whole-of-government approach is “an umbrella term describing a group of responses to the problem of increased fragmentation of the public sector and an imperative to increase integration, coordination and capacity”

[16]. At the core of the whole-of-government approach is the joint cooperation across different governmental agencies and branches. It stresses the need for better coordination and integration, centered on the overall societal goal for which the government stands

[15]. The whole-of-society approach is “a form of collaborative governance that emphasizes coordination through normative values and trust-building among a wide variety of actors”

[14]. The whole-of-society approach is derived from the whole-of-government approach because wicked problems such as obesity and pandemic preparedness usually “require more than the whole-of-government approach: solutions require involving many social stakeholders, particularly citizens”

[17]. Both whole-of-government and whole-of-society approaches are intertwined with each other and mutually complementary.

The core of the active health governance is composed of three elements: health system, social determinants of health, and lifestyle determinants of health [15,

[18][19][20][21]. The health system is defined by WHO as all the activities for which their primary purpose is to promote, restore, or maintain health. In recent years, researchers and policy makers have proposed PCC, PA, IC, CBC, etc. as the various innovative forms within health system. By carrying out four vital functions—service provision, resource generation, financing, and stewardship—the health system aims at achieving “three fundamental objectives—improving the health of the population they serve, responding to people’s expectations, and providing financial protection against the costs of ill-health”

[22].

Social determinants of Health (SDH) and lifestyle determinants of health (LDH) are the other two elements of the core. Among those factors affecting people’s health, SDH acts as the predominant role that influences individuals’ health behavior through material and psychosocial mechanisms. LDH, on the other hand, mainly concerns individual behaviors influenced by social determinants and/or health systems, especially shaped by public health policies. Clearly, lifestyle determinants are closely associated with and shaped by social determinants. It can be viewed that “adoption of health-threatening behaviors is a response to material deprivation and stress. Environments determine whether individuals take up tobacco, use alcohol, have poor diets and engage in physical inactivity. Tobacco and excessive alcohol use, and carbohydrate-dense diets, are means of coping with difficult life circumstances”

[18]. Lifestyle elements, in turn, have an active connection with social determinants of health. Different individuals have varying choices of behaviors under the same circumstances. The counteraction of health-relevant behaviors to socioeconomic status has been demonstrated in some studies

[19][20]. These studies suggest that previous research may have underestimated the influence of health behaviors to social inequalities and are important in contributing to health differences

[19][21]. Therefore, lifestyle determinants have a counter effect to circumstances around individuals, ultimately play an important role in health maintenance.

Health system dynamically interacts with social and lifestyle determinants of health. For example, health determinants affect health system performance through a series of public policies, among which, the most powerful one includes welfare redistributive policies (or the absence of such policies)

[23]. Individuals who are trapped in poverty are less likely to access to health care, more likely to suffer from catastrophic health expenditure, and result in adverse exposure and vulnerability, compared to those who stay at top of the social gradient. Moreover, the health system can improve unbiased access to care and improve the health status of citizens. The health system also influences social/lifestyle factors by mediating the differential consequences of illness in people’s lives. The role that health care plays in contributing to health differences “is increasing due to better results in disease prevention, improved diagnostic tools and treatment methods”

[24]. Thereby, health care might decrease or increase health differences between socioeconomic groups depending on whether it is distributed pro-poor or pro-rich in different service chain in relation to need

[20].

Investing in health requires investing in the health system and social and lifestyle determinants by using the lifespan/life-course approach. Strategies for intervention to health inequalities and social determinants can be adapted to cater for the most important stages of the lifespan/life-course, such as the following: (1) maternal and child health. It requires not only a promotion of excellent health care in prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal periods but also a broad range of social policies such as “employment and social protection system that recognizes the risks posed by poverty and stress in early childhood, good parental leave arrangements, support for parenting and high-quality early education and care”

[25] and universal access to primary and secondary school provision. (2) The second stage includes healthy adults. Material deprivations from unemployment or low-paid work and feelings of unfair pay in organizations with high levels of wage disparity contribute to physical and mental ill health. Occupational position is important for people’s social status and social identity, and threats of job instability affect health and wellbeing

[25][26]. (3) The third stage includes healthy older people. Healthy aging requires managing the development of chronic morbidity and improving survival and wellbeing through health systems. It also requires the development of age-friendly policies and supportive environments to enable senior citizens’ full participation in community and society through a variety of factors, including fiscal, social welfare, transport, urban planning, housing, justice, and education.

The four elements and the three approaches in the framework work jointly to impact health outcomes—health equity and health improvement. Health outcomes, in turn, can feed back to the four elements and the three approaches. Inequity in health and ill health, for instance, can negatively impact individual’s social determinants “by compromising employment opportunities and reducing income. Certain epidemic diseases can affect the functioning of social, economic and political institutions”

[23]. By contrast, health equity and better health outcomes can facilitate better governance for health and promote the conditions of SDH, LDH, and health system by acquiring occupational position, community participation and social cohesion.

2.2. Characteristics of the Proposed Framework on Active Health Governance

The proposed conceptual framework on active health governance demonstrates at least five characteristics when it is embedded in the literature we reviewed.

First of all, it is a comprehensive and holistic framework encompassing all active factors distilled from the literature and systemizing the dynamic interactions between these factors. We noted that policies or programs that only focus on one active factor can hardly achieve desirable health outcomes. Addressing integrated health services alone, for instance, while disregarding social and lifestyle determinants of health, is difficult to achieve the goals of improving health outcomes. Highlighting interactions of those factors within the framework, rather than overemphasizing a certain single element, is a prominent characteristic of this active health governance framework.

Second, it adopts a collaborative governance perspective

[27][28], e.g., whole-of-government and whole-of-society approaches. It recognizes that health equity and health improvement depend on collaboration between all levels of governments and all societal actors such as businesses, civil society, and citizens, in which all actors take shared responsibilities, form partnerships, and work together to achieve active health goals

[29]. Health is not an independent sector—it is closely linked with other complex adaptive systems with many spillover effects

[14]. Most importantly, this framework recognizes that the private sector, civil society, communities, and individuals are frequently required to engage in this active health process. Although the government is often the leader or broker, other actors, such as a strong non-governmental organization or an alliance or coalitions of organizations, can also lead and play critical roles in active health

[17].

Third, citizen empowerment is essential for active health governance. Empowerment is recognized as the combination of ability, motivation, and power opportunities [14]. For example, patient empowerment includes not only patient activation and patient participation in decision making with their health providers but also changing people’s role from passive care recipients to active agents with power and control, covering the action scope from care services to all health-related policies. By acquiring ability and motivation, citizens can be mobilized and involved in co-producing active health.

Fourth, the proposed framework emphasizes the importance of the lifespan/life-course approach to achieve health outcomes. Interventions should be different for childhood, adulthood, and older adulthood for different lifespans. The gender and race/ethnicity are other factors of targeted intervention. The policy towards older women, for instance, should be distinctive from older men because they always live longer with chronic conditions and are more likely to suffer from deprivation and social discrimination. Thus, the lifespan/life-course approach provides relevant interventions to health inequalities and social determinants for key stages of the lifespan/life-course in order to achieve active health outcomes.

Lastly, the framework highlights upstream intervention of health while seeking for treatment of ill-health. The shift in health policies from a “downstream” approach to “upstream” one reflects the awareness that active health governance should address both the care for the sick and injured and the protection of health for the entire population. The framework emphasizes research on the social determinants of health, promoting policies for protecting health rather than simply improving health care, and intervening at the level of health systems rather than health professionals

[30]. From this point, this framework on active health governance ought to be viewed as a “proactive” strategy that pays more attention to the root causes for ill health.