Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Iris Aloisi | + 2602 word(s) | 2602 | 2022-02-14 09:09:16 | | | |

| 2 | Bruce Ren | -8 word(s) | 2594 | 2022-02-18 02:15:45 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Aloisi, I. Polyamines Act as Pollen Tube Growth Protectants. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19577 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Aloisi I. Polyamines Act as Pollen Tube Growth Protectants. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19577. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Aloisi, Iris. "Polyamines Act as Pollen Tube Growth Protectants" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19577 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Aloisi, I. (2022, February 17). Polyamines Act as Pollen Tube Growth Protectants. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19577

Aloisi, Iris. "Polyamines Act as Pollen Tube Growth Protectants." Encyclopedia. Web. 17 February, 2022.

Copy Citation

Although pollen structure and morphology evolved toward the optimization of stability and fertilization efficiency, its performance is affected by harsh environmental conditions, e.g., heat, cold, drought, pollutants, and other stressors. These phenomena are expected to increase in the coming years in relation to predicted environmental scenarios, contributing to a rapid increase in the interest of the scientific community in understanding the molecular and physiological responses implemented by male gametophyte to accomplish reproduction.

plant reproduction

pollen tube growth

environmental stress

polyamines

1. Polyamines in Pollen Development

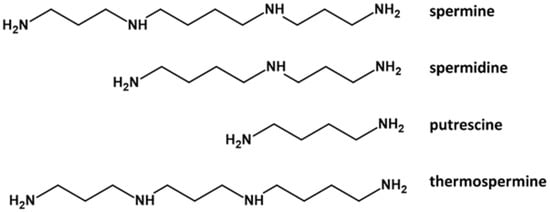

Polyamines (PAs), i.e., spermine, spermidine, and putrescine (Figure 1) are small organic polycations with a widespread presence in all living organisms [1]. Another tetra-amine, i.e., thermospermine, has been detected in archaea, diatoms, and plants, but not in animals or bacteria [2]. PAs in plants are involved in many processes, such as organogenesis, embryogenesis, floral and fruit development, leaf senescence, and plant abiotic and biotic stress responses. PAs are also highly critical in the process of plant reproduction, from pollen development to fertilization [3][4] to self-incompatibility [5]. In cells, their concentration depends on the balance among biosynthesis, degradation, and transport [6]. More generally, PAs regulate plant cell growth and are involved in external stimuli perception and in counteracting adverse environmental conditions [7][8][9]. Changes in plant PA metabolism occur in response to a variety of abiotic and biotic stresses [10]; their levels can increase dramatically, and for example, putrescine can reach up to 1.2% of dry matter, or approximately 20% of total nitrogen in stressed plants. Pas can act as cellular signals in a crosstalk with hormonal pathways, including abscisic acid (ABA) to cope with abiotic stress [11]. Similar to other aliphatic Pas, a role in defense against stresses has also been proposed for thermospermine [12].

Figure 1. The main Pas identified in plant reproductive organs. Molecules were drawn using ACD/ChemSketch Freeware software.

The researchers recently reviewed the involvement of Pas during the main pollen developmental stages, a complex and well-coordinated process governed by genetic and enzymatic processes, some of which are modulated by Pas [3]. When pollen lands on the stigma of a receptive flower, it hydrates and produces a growing pollen tube to transport sperm cells and the vegetative nucleus. The pollen tube grows through the stigma and style following a precise set of extracellular signals [13][14], including PAs, which are released into the germination medium together with RNAs, neo-synthesized proteins, and the PAs cross-linking enzyme transglutaminase (TGase), suggesting their possible involvement in pollen tube/style adhesion [15]. Pollen tube growth occurs exclusively in the apical region through the accumulation of secretory vesicles carrying new cell wall material, new plasma membrane, and proteins [16]. Methyl-esterified pectins accumulate at the extreme apex of the pollen tube and are then converted to acidic pectins, thereby stiffening the cell wall by cross-linking with calcium ions. Subsequently, the cell wall is further strengthened by substantial deposition of callose and cellulose [17]. The process of cell wall deposition and modification depends on the control of vesicular secretion and in turn on a specific organization of the cytoskeleton. All these events rely on a central regulatory system based on membrane receptor proteins, GTPases, calcium ions, intracellular pH gradients, actin-binding proteins, as well as changes in the level of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and phosphoinositides (PI) [18][19][20][21][22][23]. PAs regulate all the above-mentioned aspects of pollen tube growth, as they take part in cell-wall structuring, Ca2+ and ROS-signaling as well as the organization of the cytoskeleton [3]. This regulatory system is the target of stressful conditions that can affect one or more molecular dowels that allow the pollen tube to grow.

As pollen and pollen tube growth are critically important in sexual plant reproduction, they have been the subject of a multitude of studies dealing with those environmental changes that can impair plant reproduction in both natural and anthropized areas [24][25]. Stress-induced effects include early or delayed flowering, asynchrony between male and female reproductive development, alteration and abnormal functioning of parental tissues, and defects in male and female gametes [26]. Pollen and pollen tubes are highly sensitive to stress conditions, sometimes more than the female gametophyte [27][28], and the impact of stress on pollen viability is well documented. Scientific research has focused on how abiotic stress causes pollen damage, how pollen implements tolerance mechanisms, and how pollen from different plant varieties or genotypes may differ in stress tolerance [29][30][31].

2. Can Polyamines Ameliorate the Damaging Effect of Stress?

Similar to other plant cells, the ability of pollen to withstand stressful conditions is related to its intrinsic biochemical, physiological, and cytological characteristics, for example the production of HSPs or osmoprotectants [32], as well as the fine-tuning of ROS and Ca2+ levels and the ability to build a cell wall suitable for new conditions [33]. PAs have often been associated with the environmental stress response as they interface with various intracellular signaling processes [11][34], such as phosphorylation [35] and cation transport [8].

When plants are subjected to abiotic stress, one possible adaptive response is the increase in PA levels. The literature comprehensively describes changes in PA content in response to altered environmental conditions. For example, during heat and cold stress, PA levels change, and in some cases, PAs might also be redirected to the synthesis of uncommon PAs, the latter being more involved in thermotolerance [36]. Under cold stress, PA rebalance may increase the synthesis of ABA and/or reduce lipid peroxidation indirectly by inhibiting the synthesis of ROS [37]. Tolerance to salt stress is also mediated by PAs, which regulate Na+ and K+ fluxes [38][39]. Likewise, under salt stress, Pas might counteract drought stress by controlling Ca2+ and K+ flux, thereby causing stomata to close [40]. Exogenous putrescine can mitigate drought by reducing oxidative stress and increasing the synthesis of endogenous PAs [41]. In the osmotic stress response, PAs likely facilitate and enhance the synthesis of osmoprotectants [42]. PAs are also involved in the response to nutrient deficiencies, such as potassium [43], and in counteracting hypoxic conditions [44]. The protective effect of PAs against abiotic stresses appears therefore evident, but most likely, the effect is not strictly direct or dose dependent; moreover, the protective effect might be limited to specific cells and distinct time frames [45].

The association between susceptibility/tolerance to environmental stress and PA levels is also supported by expression changes of genes encoding for enzymes in the PA synthesis pathway in transgenic plants [46][47][48][49]. Downregulation of the spermidine synthase gene (SPDS) by RNA interference in Nicotiana tabacum showed that drought and salt stress can be counteracted by changes in PA content [50]; the mutation enhances tolerance to salinity and drought conditions due to a constant intracellular pool of putrescine (spermidine precursor) and spermine (spermidine product), thus highlighting a different action of the three PAs [51]. This is confirmed by the Arabidopsis mutant defective in spermine synthesis and consequently hypersensitive to drought and salt stress, whose effects can be mitigated by pretreatment with spermine [52]. Overexpression of the SAMDC gene in tobacco led to an accumulation of spermidine and to a concurrent increase in polyamine oxidase activity, which in turn increased the antioxidant response [53]. Similar results were obtained following overexpression of the SAMDC gene in rice [48].

The effect of PAs on pollen tubes is only partially known, and many details are missing. However, the acquired information may help to understand the role of PAs during stress conditions. When applied to pollen tubes, PAs affect several cytological parameters, such as Ca2+ and H+ flux, ROS accumulation and tube shape [54][55]. Thus, a balanced content and localization of ROS, Ca2+ and H+ is likely to normalize pollen tube growth. The action of PAs and ROS is interconnected; PAs may play a role in tip growth as precursors of ROS. In Arabidopsis thaliana, ROS accumulation at the tip correlates with pollen tube growth. In detail, the ABC transporter AtABCG28, which regulates ROS levels, is localized in secretory vesicles that fuse with the plasma membrane at the pollen tube tip. Deletion of AtABCG28 results in defective pollen tube growth, failure to localize PAs and ROS at the tip of growing pollen tube, and complete male infertility [56]. Spermidine-treated pollen tubes are initially characterized by progressive changes in shape until growth resumes, despite a larger diameter, concomitantly with extensive rearrangements of actin filaments and pH gradient [57].

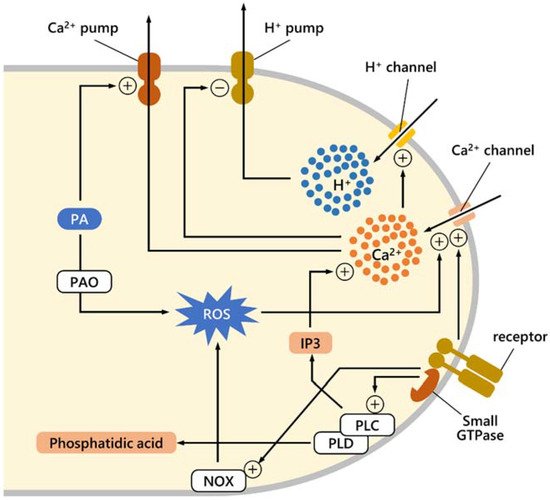

PAs, either produced internally or imported from outside, or directly targeting the surface of pollen tubes, can regulate several molecular processes during pollen tube growth, such as the proper balance of Ca2+, protons, and ROS. The mechanism is not known in detail, but currently, available data suggest possible pathways, depicted schematically in Figure 1. In the pollen tube, the exact correlation between Ca2+ and H+ fluxes and ROS synthesis is not known, although data suggest that Ca2+ and ROS may interact. The correlation between Ca2+ and H+ fluxes is also unknown, although data suggest that increasing Ca2+ precedes high growing rates in the pollen tube, whereas H+ flux follows fast growth [21]. It is assumed that both Ca2+ and H+ enter the apical region and are expelled at the subapical region; almost certainly, H+ is expelled at the level of the alkaline band, while Ca2+ can be actively pumped into organelles. As suggested for other biological systems, if PAs trigger active Ca2+ pumping, this will result in dissipation of the cytosolic Ca2+ gradient [58]. If Ca2+ levels control H+ content (either by activating H+ influx or inhibiting active H+ pumping) and if PAs promote dissipation of the Ca2+ gradient, this implies that PAs promote more H+ efflux, resulting in dissipation of the H+ gradient. The catabolism of PAs produces ROS, which in turn modulates Ca2+ [8]. Therefore, PAs could first dissipate the Ca2+ gradient, but the subsequent ROS production due to PA catabolism could trigger a new increase in Ca2+ levels. Conversely, that PAs can alter ROS levels is well-known and PA metabolism leads to ROS production because of the activity of enzymes such as diamine oxidase (DAO) and PA oxidase (PAO) [59]. Finally, the accumulation of Ca2+ levels is also regulated by plasma membrane phospholipases, i.e., phospholipases C (PLC) and phospholipases D (PLD) through distinct pathways. These enzymes modulate cytoskeleton organization [60], are involved in autophagy-mediated cytoplasmic deletion that is necessary for pollen tube emergence [61] and that affect the Ca2+ level [62].

Figure 1. Diagram illustrating some of the mechanisms regulated by PAs underlying Ca2+ and proton balance in pollen tube growth. It is supposed that the accumulation of both proton and Ca2+ ions, highlighted in the apex, depends on their influx through specific plasma membrane channels. Ion channels are under the control of other effectors; specifically, Ca2+ channels are regulated by receptors and small GTPases that mediate external signals. Ca2+ accumulation could hypothetically activate proton channels. Ca2+ levels are also controlled through another signaling pathway; the GTPase-receptor complex can activate the plasma membrane-associated phospholipase C (PLC) [62], which in turn generates IP3. The latter can stimulate the opening of Ca2+ channels. The membrane receptor system most likely also activates the production of ROS through NAD(P)H oxidase; in turn, ROS can affect Ca2+ flux. The action of PAs could be implemented in two distinct ways: PAs could activate the efflux of Ca2+ in the subapical region, while PAs could contribute to ROS production through the PAO enzyme, thus causing an increase in Ca2+ influx. The diagram also shows how the activation of PLC can lead to an increase in Ca2+ as mediated by IP3 production. Among the membrane phospholipases, phospholipase D (PLD) [63] should also be recalled because it is responsible for the production of phosphatidic acid, a chemical mediator during stressful conditions.

The question now is: can PAs play a protective role in pollen against stress? Unfortunately, the current literature reports only a limited amount of useful information. PAs may exert a protective role possibly by regulating the levels of ROS, whose content varies significantly, such as under heat stress [4]. As further evidence, the appropriate dosage of PAs was found to be important in heat-stressed tomato pollen during germination, again underscoring the protective effect of these molecules [64]. Studies in Prunus have shown that the protective effect of PAs against stress is dependent on the concentration and type of PAs [65][66], indicating that the beneficial effect of PAs is calibrated on their concentration and that concentrations above a certain threshold have inhibitory effects on pollen tube growth (PAs often have a hormetic effect, and their action involves a dose/response relationship with a biphasic effect, i.e., opposite depending to the dose). Pollen deformities caused by cold stress can also be restored by the addition of spermidine, which allows for normal growth, possibly by recalibrating the pollen tube oscillatory growth. Although cold treatment strongly alters the pH gradient, simultaneous treatment with cold and spermidine causes no apparent damage, and the pollen tubes maintain their normal morphology. The same ameliorative effect is obtained on ROS levels and Ca2+ [67]. Further evidence comes from the analysis of transgenic plants. Pollen viability under stress conditions is severely compromised when a key enzyme in PA metabolism (SAMDC) is downregulated [68][69], suggesting that optimal PA levels are required for proper functioning and pollen tolerance capacity.

The action of PAs in counteracting abiotic stresses could also be carried out in concert with enzymatic activities that metabolize PAs; among these is the cross-linking enzyme TGases [70][71], whose activity is enhanced by events that increase cytosolic Ca2+, such as rehydration, light, developmental differentiation and stresses as injury, pathogens and induction of programmed cell death (PCD). In some cases, the action of PAs could be mediated by TGase, i.e., pollen cell modeling, ion fluxes regulation and cytoskeleton organization. For more information on the relationship between transglutaminase and pollen tube growth, readers are kindly referred to more specific reviews [72].

One chemical form through which PAs could counteract abiotic stress is phenolamides (HCAAs); these are derived from the binding of PAs to phenylpropanoids, particularly hydrocinnamic acids (HCAs). These molecules have been known since the pioneering studies of Martin-Tanguy and coworkers [73], which led to the identification of HCAAs in the male reproductive organs of maize. HCAs, such as ferulic acid, are bound to the primary and secondary amine groups of PAs (putrescine, spermidine, and/or spermine). HCAAs are pollen specific and synthesized exclusively in the tapetum of developing flowers through the activity of spermidine hydroxycinnamoyltransferase (SHT) [74]. Based on the current data, the requirement of phenylpropanoids for eudicotyledon pollen fertility is unclear, although some evidence (as in the case of SHT-deficient Arabidopsis with an irregular pollen coat) suggests a structural role in the pollen cell wall [74][75]. An interesting function of phenylpropanoids is protection against UV radiation [76]; the binding of all four nitrogen atoms of spermine to HCAAs increases the UV absorbance of a single molecule by about 30% compared to spermidine (which contains only three nitrogen atoms). HCAAs, whether bound to spermidine or spermine, show absorption maxima of 315–330 nm, covering part of the UV-B and UV-A spectrum and thus helping plants cope with this abiotic stress. Finally, HCAAs also play a role as antioxidants and in plant–pollinator interactions. Tris-coumaroyl spermidine, in addition to lipids and flavonols from sunflower pollen, has been reported to stimulate insect feeding [77]. PAs contain nitrogen atoms that could be taken up by insects for their metabolism. If plant–pollinator interactions are stimulated by a cocktail of metabolites that attract pollinators, this could be one reason for the evolutionary success of angiosperms starting with the pioneer Amborella trichopoda.

Thus, the role of PAs in mitigating the detrimental effects of abiotic stresses on pollen and fertilization is exerted at several levels, including structural and biochemical. All of this underscores the substantial contribution that PAs can make to plant reproduction, but leaves several questions open, including whether the protective effect is exerted by a specific PA or by an appropriate mix of PAs, which is the optimal concentration of PAs and the best developmental stage for their action.

References

- Pegg, A.E.; Michael, A.J. Spermine synthase. Cell. Mol. life Sci. 2010, 67, 113–121.

- Michael, A.J. Polyamines in eukaryotes, bacteria, and archaea. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 14896–14903.

- Aloisi, I.; Cai, G.; Serafini-Fracassini, D.; Del Duca, S. Polyamines in pollen: From microsporogenesis to fertilization. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 155.

- Paupière, M.J.; Müller, F.; Li, H.; Rieu, I.; Tikunov, Y.M.; Visser, R.G.F.F.; Bovy, A.G. Untargeted metabolomic analysis of tomato pollen development and heat stress response. Plant Reprod. 2017, 30, 81–94.

- Yu, J.; Wang, B.; Fan, W.; Fan, S.; Xu, Y.; Liu, C.; Lv, T.; Liu, W.; Wu, L.; Xian, L.; et al. Polyamines involved in regulating self-incompatibility in apple. Genes 2021, 12, 1797.

- Antognoni, F.; Agostani, S.; Spinelli, C.; Koskinen, M.; Elo, H.; Bagni, N. Effect of bis (guanylhydrazones) on growth and polyamine uptake in plant cells. J. Plant Growth Regul. 1999, 18, 39–44.

- Tiburcio, A.F.; Altabella, T.; Bitrián, M.; Alcázar, R. The roles of polyamines during the lifespan of plants: From development to stress. Planta 2014, 240, 1–18.

- Pottosin, I.; Shabala, S. Polyamines control of cation transport across plant membranes: Implications for ion homeostasis and abiotic stress signaling. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 154.

- Chen, D.; Shao, Q.; Yin, L.; Younis, A.; Zheng, B. Polyamine Function in Plants: Metabolism, Regulation on Development, and Roles in Abiotic Stress Responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 9, 1945.

- Gerlin, L.; Baroukh, C.; Genin, S. Polyamines: Double agents in disease and plant immunity. Trends Plant Sci. 2021, 26, 1061–1071.

- Alcázar, R.; Altabella, T.; Marco, F.; Bortolotti, C.; Reymond, M.; Koncz, C.; Carrasco, P.; Tiburcio, A.F. Polyamines: Molecules with regulatory functions in plant abiotic stress tolerance. Planta 2010, 231, 1237–1249.

- Marina, M.; Sirera, F.V.; Rambla, J.L.; Gonzalez, M.E.; Blázquez, M.A.; Carbonell, J.; Pieckenstain, F.L.; Ruiz, O.A. Thermospermine catabolism increases Arabidopsis thaliana resistance to Pseudomonas viridiflava. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 1393–1402.

- Kessler, S.A.; Grossniklaus, U. She’s the boss: Signaling in pollen tube reception. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2011, 14, 622–627.

- Guan, Y.; Guo, J.; Li, H.; Yang, Z. Signaling in Pollen Tube Growth: Crosstalk, Feedback, and Missing Links. Mol. Plant 2013, 6, 1053–1064.

- Di Sandro, A.; Del Duca, S.; Verderio, E.; Hargreaves, A.J.; Scarpellini, A.; Cai, G.; Cresti, M.; Faleri, C.; Iorio, R.A.; Hirose, S.; et al. An extracellular transglutaminase is required for apple pollen tube growth. Biochem. J. 2010, 429, 261–271.

- Wang, X.; Sheng, X.; Tian, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y. Organelle movement and apical accumulation of secretory vesicles in pollen tubes of Arabidopsis thaliana depend on class XI myosins. Plant J. 2020, 104, 1685–1697.

- Mollet, J.C.; Leroux, C.; Dardelle, F.; Lehner, A. Cell Wall Composition, Biosynthesis and Remodeling during Pollen Tube Growth. Plants 2013, 2, 107–147.

- Cheung, A.Y.; Chen, C.Y.; Tao, L.Z.; Andreyeva, T.; Twell, D.; Wu, H.-M. Regulation of pollen tube growth by Rac-like GTPases. J. Exp. Bot. 2003, 54, 73–81.

- Potocky, M.; Jones, M.A.; Bezvoda, R.; Smirnoff, N.; Zarsky, V. Reactive oxygen species produced by NADPH oxidase are involved in pollen tube growth. New Phytol. 2007, 174, 742–751.

- Heilmann, I.; Ischebeck, T. Male functions and malfunctions: The impact of phosphoinositides on pollen development and pollen tube growth. Plant Reprod. 2016, 29, 3–20.

- Winship, J.L.; Rounds, C.; Hepler, K.P. Perturbation analysis of calcium, alkalinity and secretion during growth of lily pollen tubes. Plants 2017, 6, 3.

- Muschietti, J.P.; Wengier, D.L. How many receptor-like kinases are required to operate a pollen tube. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2018, 41, 73–82.

- Çetinbaş-Genç, A.; Conti, V.; Cai, G. Let’s shape again: The concerted molecular action that builds the pollen tube. Plant Reprod. 2022.

- De Storme, N.; Geelen, D. The impact of environmental stress on male reproductive development in plants: Biological processes and molecular mechanisms. Plant Cell Environ. 2014, 37, 1–18.

- Mesihovic, A.; Iannacone, R.; Firon, N.; Fragkostefanakis, S. Heat stress regimes for the investigation of pollen thermotolerance in crop plants. Plant Reprod. 2016, 29, 93–105.

- Lohani, N.; Singh, M.B.; Bhalla, P.L. High temperature susceptibility of sexual reproduction in crop plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 555–568.

- Snider, J.L.; Oosterhuis, D.M.; Loka, D.A.; Kawakami, E.M. High temperature limits in vivo pollen tube growth rates by altering diurnal carbohydrate balance in field-grown Gossypium hirsutum pistils. J. Plant Physiol. 2011, 168, 1168–1175.

- Arshad, M.S.; Farooq, M.; Asch, F.; Krishna, J.S.V.; Prasad, P.V.V.; Siddique, K.H.M. Thermal stress impacts reproductive development and grain yield in rice. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 115, 57–72.

- Seif Barghi, S.; Mostafaii, H.; Peighami, F.; Asghari Zakaria, R.; Farjami Nejhad, R. Response of in Vitro Pollen Germination and Cell Membrane Thermostabilty of Lentil Genotypes to High Temperature. Int. J. Agric. Res. Rev. 2013, 3, 13–20.

- Jiang, Y.; Bueckert, R.; Warkentin, T.; Davis, A.R. High Temperature Effects on in vitro Pollen Germination and Seed Set in Field Pea. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2018, 98, 71–80.

- Singh, A.; Antre, S.H.; Ravikumar, R.L.; Kuchanur, P.H.; Lohithaswa, H.C. Genetic evidence of pollen selection mediated phenotypic changes in maize conferring transgenerational heat-stress tolerance. Crop Sci. 2020, 60, 1907–1924.

- Nagib, A.; Setsuko, K. Comparative analyses of the proteomes of leaves and flowers at various stages of development reveal organ-specific functional differentiation of proteins in soybean. Proteomics 2009, 9, 4889–4907.

- Tenhaken, R. Cell wall remodeling under abiotic stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 5, 771.

- Upadhyay, R.K.; Shao, J.; Mattoo, A.K. Genomic analysis of the polyamine biosynthesis pathway in duckweed Spirodela polyrhiza L.: Presence of the arginine decarboxylase pathway, absence of the ornithine decarboxylase pathway, and response to abiotic stresses. Planta 2021, 254, 1–17.

- Gupta, K.; Gupta, B.; Ghosh, B.; Sengupta, D.N. Spermidine and abscisic acid-mediated phosphorylation of a cytoplasmic protein from rice root in response to salinity stress. Acta Physiol. Plant 2012, 34, 29–40.

- Roy, M.; Ghosh, B. Polyamines, both common and uncommon, under heat stress in rice (Oryza sativa) callus. Physiol. Plant 1996, 98, 196–200.

- Amini, S.; Maali-Amiri, R.; Kazemi-Shahandashti, S.-S.; López-Gómez, M.; Sadeghzadeh, B.; Sobhani-Najafabadi, A.; Kariman, K. Effect of cold stress on polyamine metabolism and antioxidant responses in chickpea. J. Plant Physiol. 2021, 258, 153387.

- Shabala, S.; Cuin, T.A.; Pottosin, I. Polyamines prevent NaCl-induced K+ efflux from pea mesophyll by blocking non-selective cation channels. FEBS Lett. 2007, 581, 1993–1999.

- Do, P.T.; Drechsel, O.; Heyer, A.G.; Hincha, D.K.; Zuther, E. Changes in free polyamine levels, expression of polyamine biosynthesis genes, and performance of rice cultivars under salt stress: A comparison with responses to drought. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 182.

- Liu, K.; Fu, H.; Bei, Q.; Luan, S. Inward potassium channel in guard cells as a target for polyamine regulation of stomatal movements. Plant Physiol. 2000, 124, 1315–1326.

- Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Pan, X.; Jiang, Q.; Xi, Z. Exogenous putrescine alleviates drought stress by altering reactive oxygen species scavenging and biosynthesis of polyamines in the seedlings of Cabernet Sauvignon. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 2881.

- Sengupta, A.; Chakraborty, M.; Saha, J.; Gupta, B.; Gupta, K. Polyamines: Osmoprotectants in Plant Abiotic Stress Adaptation. In Osmolytes and Plants Acclimation to Changing Environment: Emerging Omics Technologies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 97–127.

- Papenfus, H.B.; Kulkarni, M.G.; Stirk, W.A.; Finnie, J.F.; Van Staden, J. Effect of a commercial seaweed extract (Kelpak®) and polyamines on nutrient-deprived (N, P and K) okra seedlings. Sci. Hortic. 2013, 151, 142–146.

- Nada, K.; Iwatani, E.; Doi, T.; Tachibana, S. Effect of putrescine pretreatment to roots on growth and lactate metabolism in the root of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) under root-zone hypoxia. J. Jpn. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2004, 73, 337–339.

- Pandolfi, C.; Pottosin, I.; Cuin, T.; Mancuso, S.; Shabala, S. Specificity of polyamine effects on NaCl-induced ion flux kinetics and salt stress amelioration in plants. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010, 51, 422–434.

- Capell, T.; Bassie, L.; Christou, P. Modulation of the polyamine biosynthetic pathway in transgenic rice confers tolerance to drought stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 9909–9914.

- Waie, B.; Rajam, M.V. Effect of increased polyamine biosynthesis on stress responses in transgenic tobacco by introduction of human S-adenosylmethionine gene. Plant Sci. 2003, 164, 727–734.

- Roy, M.; Wu, R. Overexpression of S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase gene in rice increases polyamine level and enhances sodium chloride-stress tolerance. Plant Sci. 2002, 163, 987–992.

- Cheng, L.; Zou, Y.; Ding, S.; Zhang, J.; Yu, X.; Cao, J.; Lu, G. Polyamine accumulation in transgenic tomato enhances the tolerance to high temperature stress. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2009, 51, 489–499.

- Yamaguchi, K.; Takahashi, Y.; Berberich, T.; Imai, A.; Miyazaki, A.; Takahashi, T.; Michael, A.; Kusano, T. The polyamine spermine protects against high salt stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580, 6783–6788.

- Choubey, A.; Rajam, M.V. RNAi-mediated silencing of spermidine synthase gene results in reduced reproductive potential in tobacco. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2018, 24, 1069–1081.

- Yamaguchi, K.; Takahashi, Y.; Berberich, T.; Imai, A.; Takahashi, T.; Michael, A.J.; Kusano, T. A protective role for the polyamine spermine against drought stress in Arabidopsis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 352, 486–490.

- Seo, S.Y.; Kim, Y.J.; Park, K.Y. Increasing polyamine contents enhances the stress tolerance via reinforcement of antioxidative properties. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1331.

- Wu, J.; Shang, Z.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Moschou, P.N.; Sun, W.; Roubelakis-Angelakis, K.A.; Zhang, S. Spermidine oxidase-derived H2O2 regulates pollen plasma membrane hyperpolarization-activated Ca2+-permeable channels and pollen tube growth. Plant J. 2010, 63, 1042–1053.

- Aloisi, I.; Cai, G.; Tumiatti, V.; Minarini, A.; Del Duca, S. Natural polyamines and synthetic analogs modify the growth and the morphology of Pyrus communis pollen tubes affecting ROS levels and causing cell death. Plant Sci. 2015, 239, 92–105.

- Do, T.H.T.; Choi, H.; Palmgren, M.; Martinoia, E.; Hwang, J.-U.; Lee, Y. Arabidopsis ABCG28 is required for the apical accumulation of reactive oxygen species in growing pollen tubes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 12540–12549.

- Aloisi, I.; Cai, G.; Faleri, C.; Navazio, L.; Serafini-Fracassini, D.; Del Duca, S. Spermine regulates pollen tube growth by modulating Ca2+-dependent actin organization and cell wall structure. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1–20.

- Pottosin, I.; Velarde-Buendia, A.M.; Bose, J.; Fuglsang, A.T.; Shabala, S. Polyamines cause plasma membrane depolarization, activate Ca2+-, and modulate H+-ATPase pump activity in pea roots. J. Exp.Bot. 2014, 65, 2463–2472.

- Benkő, P.; Jee, S.; Kaszler, N.; Fehér, A.; Gémes, K. Polyamines treatment during pollen germination and pollen tube elongation in tobacco modulate reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide homeostasis. J. Plant Physiol. 2020, 244, 153085.

- Jia, Q.; Zhang, S.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Q. Phospholipase Dδ regulates pollen tube growth by modulating actin cytoskeleton organization in Arabidopsis. Plant Signal. Behav. 2021, 16, 1915610.

- Zhao, P.; Zhou, X.-M.; Zhao, L.-L.; Cheung, A.Y.; Sun, M.-X. Autophagy-mediated compartmental cytoplasmic deletion is essential for tobacco pollen germination and male fertility. Autophagy 2020, 16, 2180–2192.

- Dowd, P.E.; Coursol, S.; Skirpan, A.L.; Kao, T.H.; Gilroy, S. Petunia phospholipase C1 is involved in pollen tube growth. Plant Cell 2006, 18, 1438–1453.

- Pleskot, R.; Pejchar, P.; Bezvoda, R.; Lichtscheidl, I.K.; Wolters-Arts, M.; Marc, J.; Žárský, V.; Potocký, M. Turnover of phosphatidic acid through distinct signaling pathways affects multiple aspects of pollen tube growth in tobacco. Front. Plant Sci. 2012, 3, 54.

- Song, J.; Nada, K.; Tachibana, S. Ameliorative effect of polyamines on the high temperature inhibition of in vitro pollen germination in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.). Sci. Hortic. 1999, 80, 203–212.

- Wolukau, J.N.; Zhang, S.; Xu, G.; Chen, D. The effect of temperature, polyamines and polyamine synthesis inhibitor on in vitro pollen germination and pollen tube growth of Prunus mume. Sci. Hortic. 2004, 99, 289–299.

- Sorkheh, K.; Shiran, B.; Rouhi, V.; Khodambashi, M.; Wolukau, J.N.; Ercisli, S. Response of in vitro pollen germination and pollen tube growth of almond (Prunus dulcis Mill.) to temperature, polyamines and polyamine synthesis inhibitor. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2011, 39, 749–757.

- Kazemi-Shahandashti, S.S.; Maali-Amiri, R. Global insights of protein responses to cold stress in plants: Signaling, defence, and degradation. J. Plant Physiol. 2018, 226, 123–135.

- Song, J.; Nada, K.; Tachibana, S. Suppression of S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase activity is a major cause for high-temperature inhibition of pollen germination and tube growth in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.). Plant Cell Physiol. 2002, 43, 619–627.

- Chen, M.; Chen, J.; Fang, J.; Guo, Z.; Lu, S. Down-regulation of S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase genes results in reduced plant length, pollen viability, and abiotic stress tolerance. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2014, 116, 311–322.

- Mandrone, M.; Antognoni, F.; Aloisi, I.; Potente, G.; Poli, F.; Cai, G.; Faleri, C.; Parrotta, L.; Del Duca, S. Compatible and incompatible pollen-styles interaction in Pyrus communis l. Show different transglutaminase features, polyamine pattern and metabolomics profiles. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 741.

- Aloisi, I.; Cai, G.; Serafini-Fracassini, D.; Del Duca, S. Transglutaminase as polyamine mediator in plant growth and differentiation. Amino Acids 2016, 48, 2467–2478.

- Cai, G.; Serafini-Fracassini, D.; Del Duca, S. Regulation of pollen tube growth by transglutaminase. Plants 2013, 2, 87–106.

- Martin-Tanguy, J.; Cabanne, F.; Perdrizet, E.; Martin, C. The distribution of hydroxycinnamic acid amides in flowering plants. Phytochemistry 1978, 17, 1927–1928.

- Grienenberger, E.; Besseau, S.; Geoffroy, P.; Debayle, D.; Heintz, D.; Lapierre, C.; Pollet, B.; Heitz, T.; Legrand, M. A BAHD acyltransferase is expressed in the tapetum of Arabidopsis anthers and is involved in the synthesis of hydroxycinnamoyl spermidines. Plant J. 2009, 58, 246–259.

- Hafidh, S.; Fíla, J.; Honys, D. Male gametophyte development and function in angiosperms: A general concept. Plant Reprod. 2016, 29, 31–51.

- Youhnovski, N.; Werner, C.; Hesse, M. N, N′, N ″-Triferuloylspermidine, a new UV absorbing polyamine derivative from pollen of Hippeastrum× hortorum. Z. Naturforsch. C 2001, 56, 526–530.

- Lin, S.; Mullin, C.A. Lipid, polyamide, and flavonol phagostimulants for adult western corn rootworm from sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) pollen. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 1223–1229.

More

Information

Subjects:

Plant Sciences

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

947

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

18 Feb 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No