| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Doris Ilicic | + 4998 word(s) | 4998 | 2022-02-10 07:08:28 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | -89 word(s) | 4909 | 2022-02-17 02:18:28 | | | | |

| 3 | Doris Ilicic | + 86 word(s) | 4995 | 2022-02-17 12:18:02 | | |

Video Upload Options

Although aquatic and parasitic fungi have been well known for more than 100 years, they have only recently received increased awareness due to their key roles in microbial food webs and biogeochemical cycles. There is growing evidence indicating that fungi inhabit a wide range of marine habitats, from the deep sea all the way to surface waters, and recent advances in molecular tools, in particular metagenome approaches, reveal that their diversity is much greater and their ecological roles more important than previously considered. Parasitism constitutes one of the most widespread ecological interactions in nature, occurring in almost all environments. Despite that, the diversity of fungal parasites, their ecological functions, and, in particular their interactions with other microorganisms remain largely speculative, unexplored and are often missing from current theoretical concepts in marine ecology and biogeochemistry. In this review, we summarize and discuss recent research avenues on parasitic fungi and their ecological potential in marine ecosystems, e.g., the fungal shunt, and emphasize the need for further research.

1. Marine Fungi

2. Parasitic Fungi in Marine Ecosystems

2.1. Aphelida

2.2. Rozellomycota

2.3. Microsporidia

2.4. Chytridiomycota

2.5. Oomycota - Fungi like organisms

Many species of heterotrophic stramenopiles such as representatives of the Oomycota (oomycetes) are common in the marine environment and known to infect several marine macroalgal species and planktonic diatoms [21]. In particular, oomycetes infecting marine phytoplankton comprise several marine representatives such as Lagenisma coscinodisci Drebes, which was reported as an endobiotic parasite of the centric diatom Coscinodiscus centralis Ehrenberg from the North Sea [111]. Furthermore, the endoparasitic, saprolegniaceous oomycete Ectrogella Zopf is a parasite in diatoms and, according to Sparrow [112], outbreaks of Ectrogella perforans Petersen may attain epidemic proportions in the marine pennate diatom Licmophora Agardh [113]. Other representatives can be found in Table 1. Oomycota, as other zoosporic fungi, reproduce asexually by means of flagellated zoospores that are produced in zoosporangia [21][113][114], and, as members of the ARM clade, they have been recognized as endoparasites [115]. Despite similarities in life cycles, it is important to highlight the fundamental difference between oomycetes and zoosporic fungi—oomycetes are stramenopiles, a heterotrophic sister group of, e.g., brown algae and diatoms [104]. Hence, oomycetes have predominantly cellulosic walls [113] in contrast to zoosporic fungi that are characterized by chitinaceous cell walls. Although oomycetes have frequently been reported in marine environments [7][21], not much is known about their biology and ecology. However, these parasitoids are known to play a significant role in breaking down blooms of their hosts, i.e., diatoms, and might also play similar roles in the marine food web as those of zoosporic true fungi [115].

| Parasite | Host | Literature | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aphelida | Pseudaphelidium drebesii | Thalassiosira punctigera | [116] |

| Chytrids | Chytridium megastomum | Ceramium | [117] |

| Chytridium polysiphonae | Sphacelaria, Pyaiella, Centroceras | [66][104][117] | |

| Coenomyces sp | Cladophora | [66] | |

| Dinomyces arenysensis | Dinoflagellates | [99] | |

| Olpidium rostiferum | Cladophora, Pseudo-nitzschia, | [66][104][118] | |

| Rhizophydium | Nitzschia, Rhizosolenia, Chaetoceros | [119] | |

| Rhizophydium aestuarii | Codium fragile | [99] | |

| Rhizophydium globosum | - | [120] | |

| Rhizophydium littoreum | Codium, Cancer anthonyi, Bryopsis | [99][117][121] | |

| Thalassochytrium gracilariopsis | Gracilariopsis | [99][100] | |

| Microsporidia | Loma trichiuri | Trichiurus savala | [88] |

| Microsporidium aplysiae | Aplysia californica | [122] | |

| Microsporidium cerebralis | Salmo salar | [88] | |

| Nematocenator marisprofundi | Desmodora marci | [123] | |

| Nosema pariacanthi | Priacanthus boops | [88] | |

| Oogranate pervascens | Maculaura sp. | [88] | |

| Pleistophora finisterrensis | Micromesistius poutassou | [124] | |

| Pleistophora hippoglossoideos | Hippoglossoides limandoides | [88] | |

| Pleistophora littoralis | Blennius pholis | [125] | |

| Pleistophora senegalensis | Sparus aurata | [126] | |

| Sporanauta perivermis | Odontophora rectangula | [87] | |

| Thelohania butleri | Pandalus jordani | [127] | |

| Unikaryon legeri | Meiogymnophallus minutus | [128] | |

| Oomyocta | Cryothecomonas longipes | Thalassiosira, Pirsonia, Rhizosolenia | [129] |

| Diatomophthora drebesii = Olpidiopsis drebesii | Rhizosolenia imbricata | [115][130] | |

| Ectrogella eurychasmoides | Licmophora lyngbyei | [131] | |

| Ectrogella marina | Chlorodendron subsalsum | [103] | |

| Ectrogella perforans | Fragilaria, Licmophora, Podocystis, Striatella, Synedra, Thalassionema | [132] | |

| Eurychasma dicksonii | Ectocarpus, Feldmannia, Punctaria, Pylaiella, Stictyosiphon, Striaria | [23] | |

| Eurychasmidium tumefaciens | Ceramium | [117] | |

| Lagenisma coscinodisci[117] | Coscinodiscus | [111][133][134] | |

| Miracula helgolandica | Pseudo-nitzschia pungens | [130] | |

| Olpidiopsis porphyrae | Bangia, Porphyra | [117] | |

| Petersenia lobata | Aglaothamnion, Callithamnion, Ceramium, Gymnothamnion, Herposiphonia, Polysiphonia, Pylaiella, Seirospora, Spermothamnion | [117] | |

| Petersenia palmariae | Palmaria mollis[117] | [135] | |

| Petersenia pollagaster | Chondrus | [117] | |

| Pontisma antithamnionis | Antithamnion | [117] | |

| Pontisma feldmannii | Falkenbergia, Trailliella | [117] | |

| Pontisma lagenidioides | Ceramium, Chaetomorpha, Valoniopsis | [66] | |

| Pythium marinum | - | [117] | |

| Pythium porphyrae | Porphyra | [117] | |

| Sirolpidium andreei | Acrosiphonia, Ceramium, Ectocarpus, Spongomorpha | [117] | |

| Sirolpidium bryopsidis | Cladophora, Rhizoclonium | [117] | |

| Rozellomycota | Rozella marina | Chytridium polysiphoniae | [136] |

3. Host Specificity

4. Eco-Evolutionary Dynamics

5. Diversity in Marine Ecosystems

Numbers of studies addressing diversity and abundances of Chytridiomycota are increasing with the improvement of molecular tools, in particular metagenomics approaches. Yet, information on their ecological role remains scarce. Efforts to retrieve such information due to the limited availability of model systems in culture [39][93][147] have been mainly focused on freshwater systems with a few, more recent, marine studies. Studies using next-generation sequencing technologies have revealed the prevalence of Chytridiomycota in both arctic and temperate marine habitats. Masana et al. [148] reported that Chytridimycota accounted for more than 60% of the rDNA sequences sampled in six near-shore sites in Europe, and were the most abundant fungal group in Arctic and sub-Arctic coastal habitats [6][80][89]. Although there are large numbers of described species of parasitic chytrids [20], only a few parasitic chytrid species have been genome sequenced and their phylogenetic positions clarified: Rhizophydium littoreum [120], Thalassochytrium gracilariopsis and Chytridium polysiphoniae (=Algochytrops polysiphoniae) [15][104]. Gaps in the reference databases relating to taxonomic coverage and marker coverage and the general lack of high quality, long sequence data are some of the major constraints for Chytridiomycota taxonomy [149][150]. Since fungi are phylogenetically diverse, DNA metabarcoding studies typically use markers that vary depending on the taxonomic group of interest and the resolution desired [149]. To overcome these drawbacks, Heeger et al. [150] created a long-read (ca. 4500 bp) bioinformatics pipeline that results in rates of sequencing error and chimera detection that are comparable to typical short-read analyses. The approach thus enabled the use of three different rRNA gene reference databases, thereby providing significant improvements in taxonomic classification over any single gene marker approach. Nevertheless, it is difficult to determine species composition and function (e.g., parasitic or saprotrophic) by analyzing environmental DNA alone [15]. Culturing, single cell PCR methods and whole genome sequencing [39][151] will presumably improve the representation of chytrids in future sequence databases.

6. Ecological Roles of Fungal Parasites

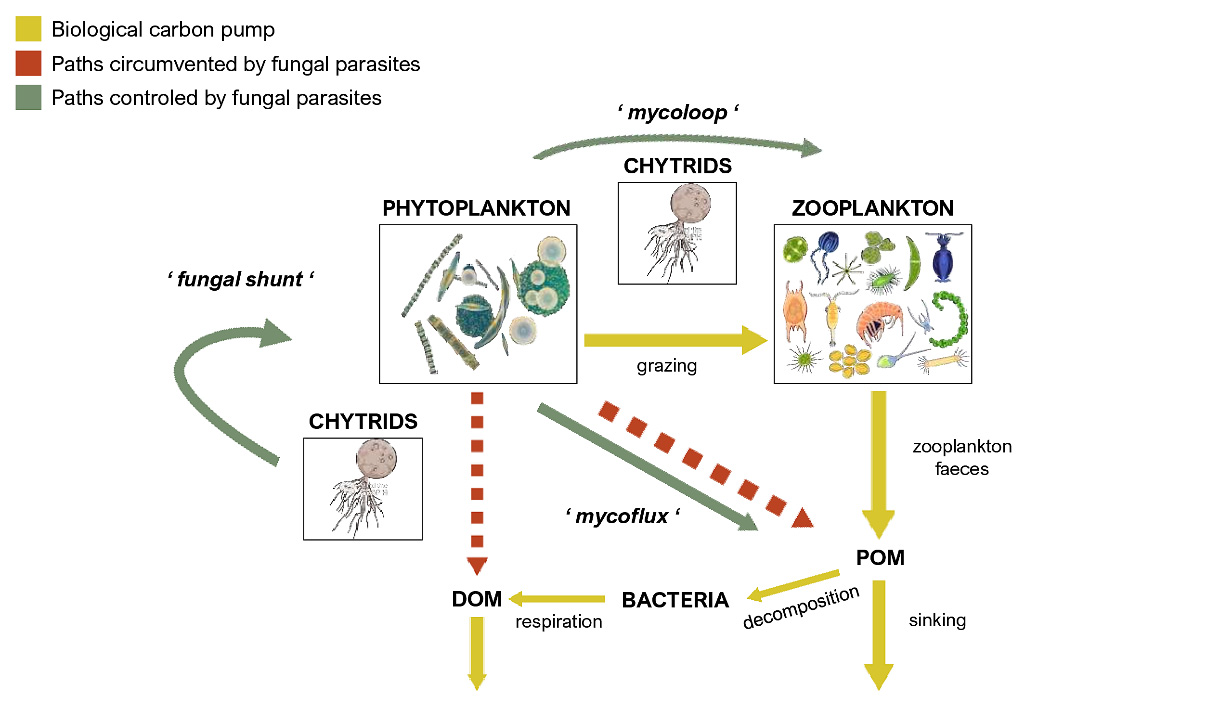

Besides their ubiquitous nature, the importance of parasites lies also in the ecological roles they hold. By regulating host populations and mediating interspecific competition between hosts and other species [152], they affect community structure [153], but can also alter biochemical cycles, change productivity, increase trophic chain length and number of links [52], and cause changes in the topology of the trophic network and functioning of the ecosystem [154]. Thus, fungal parasites, infecting phytoplankton as primary producers, change the flow of carbon (C) in aquatic ecosystems. This process, named “mycoloop” [155], proposes that fungal infections of phytoplankton hosts transfer once inaccessible organic matter (OM) from large, inedible hosts to zooplankton by producing zoospores [51][55][154]. Zoospores are rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) and cholesterol [34][45][50][52][55][156], they have relatively low carbon to nutrient ratios [54][157] and synthesize sterols de novo [53], which makes them a nutrient rich food source for grazers such as zooplankton. Hence, the presence of chytrids may not only affect the quantity of food that is being transferred, but also its quality [54][55]. It has been suggested that fungal infections may also modulate algal-bacterial interactions [158]. By utilizing their phytoplankton hosts and causing massive cell lysis, fungi provide C substrates [110] in terms of dissolved organic matter (DOM) and therefore activate the microbial loop [38][159]. In contrast, Klawonn et al. [160] have recently demonstrated that this may not be the case since fungal parasites very efficiently utilize their hosts’ cellular contents and that C and N compounds are most efficiently transferred to attached sporangia, and the developed zoospores therein. Consequently, the overall photosynthetically active biomass is reduced, as is the phytoplankton-derived contribution to the dissolved organic carbon (DOC) pool. This process, where photosynthetic carbon is bypassed from the microbial loop to fungal parasites has been called “fungal shunt” and it promotes zooplankton-mediated over microbe-mediated remineralization [160]. Multiple lines of evidence suggest that fungi play important ecological roles in marine ecosystems, yet our knowledge is still scarce. Current research is mostly focused on freshwater habitats, and we can only speculate how these results apply for the fungal parasites inhabiting marine waters.

7. Biological Carbon Pump

The biological carbon pump comprises phytoplankton cells, their consumers and the bacteria that assimilate their waste, which play a central role in the global carbon cycle by delivering carbon from the atmosphere to the deep sea, where it is concentrated and sequestered for centuries [161][162]. Photosynthetically active phytoplankton in the euphotic zone (0–200 m depth) transforms dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) to organic carbon, both dissolved and particulate forms [162]. The dissolved fraction is mainly respired by bacteria and the remaining refractory matter (RDOM) sinks and is mixed into the deep sea via the so-called microbial carbon pump (MCP) [163]. Considering the high efficiency of fungal parasites in utilizing OM from their hosts through the fungal shunt [160], infections can lead to substantially lower the contribution of phytoplankton derived OM to the DOM pool, which would consequently decrease the efficiency of the microbial carbon pump. Nevertheless, the particulate fraction is more significant when it comes to carbon export to the deeper layers of the ocean [139]. It is known that phytoplankton releases transparent polymeric particles (TEP)—gel-like, sticky particles predominantly composed of acidic polysaccharides [164]. Due to their high abundance in seawater and their surface reactivity, TEP scavenge trace elements (e.g., Fe and Th) and are the key agents for increasing the coagulation efficiency of physical aggregation processes [165]. Thus, TEP have an important role in biogeochemical fluxes and consequently, the efficiency of the biological carbon pump [166]. Mass flocculation and subsequent sedimentation of phytoplankton, especially diatoms, as large, rapidly sinking aggregates occur oceanwide and represent a major global sink for carbon. It has been shown that these larger, recalcitrant phytoplankton cells serve as preferential hosts for fungal parasites such as chytrids [26][144][161]. Grossart et al. [39] introduced the term “mycoflux” which refers to any fungal interaction leading to aggregation or disintegration of organic matter. On the one hand, by taking up the nutrients from their hosts, chytrids may decrease the exudation of TEP and thus, indirectly affect aggregation processes leading to a decreased efficiency of carbon sequestration. On the other hand, fungal infections are often lethal and lead to fragmentation of large phytoplankton cells [36][45][167], making them more edible to zooplankton which then substantially contribute to carbon pump efficiency by excretion of fast-sinking fecal pellets. The overall transfer efficiency of the biological carbon pump is therefore determined by a combination of different factors: seasonality; composition of phytoplankton species; fragmentation of particles by zooplankton; solubilization of particles by microbes [168]; and presumably presence of fungal parasites on phytoplankton species [39][157] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Fungal parasites are key components of the biological carbon pump. Fungal parasites take up phytoplankton-derived photosynthetic carbon (‘fungal shunt’) and thus lower the contribution to the DOM and POM pools. Through ‘mycoflux’, fungi control POM aggregation process, either decreasing (parasitic fungi), or increasing (saprotrophic fungi) the aggregation rate by promoting active aggregation via hyphae growth. Via fragmentation of large phytoplankton cells and redirecting carbon directly to zooplankton (‘mycoloop’) they can also indirectly modulate carbon sequestration via sinking zooplankton faeces.

As shown, fungal parasites significantly change the fate of photosynthetically derived carbon. Infecting large phytoplankton cells, they potentially circumvent the microbial carbon pump and consequently direct the carbon from phytoplankton to zooplankton, either via (1) mycoloop, mycoflux, and fungal shunt, or by (2) active fragmentation of their hosts. Thus, it is important to include fungal parasites into general biogeochemical concepts, e.g., the biological carbon pump and C and N cycling, since they significantly affect the efficiency of carbon sequestration, i.e., controlling the magnitude of the overall organic matter sinking flux. Our understanding of ocean biogeochemistry is of pivotal importance for climate and human-induced changes in food web dynamics, biogeochemical cycles and their feedbacks to future climate. Thus, incorporating fungal parasites into concepts and models is necessary for developing a more integrated view of the ocean carbon cycle, in particular the biological carbon pump efficiency, to better predicting and thus mitigating the negative effects of current global change.

8. Summary Points

- Severe reference database gaps and need for long sequence data are still a major

limitation when studying fungal parasites; - Fungal parasites are important components of marine food webs;

- Transfer efficiency of the biological carbon pump is highly affected by the presence of

fungal parasites on phytoplankton cells (both directions); - We are missing enough model systems to study the ecology of parasitic fungi;

- Linkage of different OMICS tools, i.e., metagenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics and

metabolomics could give us better insights into their ecological importance.

9. Future Perspectives

- Further tool development by linking OMICS tools and experiments;

- Rapid changes in environmental factors due to global warming can have major effects

on fungal parasites in marine ecosystems, either indirectly, by affecting their

phytoplankton hosts, or directly, by affecting the parasites themselves; - Thus, we highlight the need for more global and systematic ecological studies of

fungal parasites in marine ecosystems.

References

- Richards, T.A.; Jones, M.D.M.; Leonard, G.; Bass, D. Marine Fungi: Their Ecology and Molecular Diversity. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2011, 4, 495–522.

- Pang, K.L.; Overy, D.P.; Jones, E.G.; da Luz Calado, M.; Burgaud, G.; Walker, A.K.; Johnson, J.A.; Kerr, R.G.; Cha, H.J.; Bills, G.F. ‘Marine fungi’ and ‘marine-derived fungi’ in natural product chemistry research: Toward a new consensual definition. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2016, 30, 163–175.

- Tisthammer, K.H.; Cobian, G.; Amend, A.S. Global biogeography of marine fungi is shaped by the environment. Fungal Ecol. 2016, 19, 39–46.

- Wang, X.; Singh, P.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Johnson, Z.I.; Wang, G. Distribution and Diversity of Planktonic Fungi in the West Pacific Warm Pool. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101523.

- Van den Wyngaert, S.; Kagami, M. Fungi and Chytrids. Reference Module in Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-819166-8.00005-0 (accessed on 1 January 2021).

- Hassett, B.T.; Ducluzeau, A.L.L.; Collins, R.E.; Gradinger, R. Spatial distribution of aquatic marine fungi across the western Arctic and sub-arctic. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 19, 475–484.

- Hassett, B.T.; Borrego, E.J.; Vonnahme, T.R.; Rämä, T.; Kolomiets, M.V.; Gradinger, R. Arctic marine fungi: Biomass, functional genes, and putative ecological roles. ISME J. 2019, 13, 1484–1496.

- Varrella, S.; Barone, G.; Tangherlini, M.; Rastelli, E.; Dell’Anno, A.; Corinaldesi, C. Diversity, Ecological Role and Biotechnological Potential of Antarctic Marine Fungi. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 391.

- Jones, E.B.G.; Pang, K.-L. Tropical aquatic fungi. Biodivers. Conserv. 2011, 21, 2403–2423.

- Damare, S.; Raghukumar, C.; Raghukumar, S. Fungi in deep-sea sediments of the Central Indian Basin. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2006, 53, 14–27.

- Giddings, L.-A.; Newman, D.J. Extremophilic Fungi from Marine Environments: Underexplored Sources of Antitumor, Anti-Infective and Other Biologically Active Agents. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 62. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-3397/20/1/62/htm (accessed on 19 January 2022).

- Rojas-Jimenez, K.; Rieck, A.; Wurzbacher, C.; Jürgens, K.; Labrenz, M.; Grossart, H.-P. A Salinity Threshold Separating Fungal Communities in the Baltic Sea. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 680.

- Raghukumar, S. The Marine Environment and the Role of Fungi. In Fungi in Coastal and Oceanic Marine Ecosystems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 17–38.

- Raghukumar, S. Fungi in coastal and oceanic marine ecosystems: Marine fungi. In Fungi in Coastal and Oceanic Marine Ecosystems: Marine Fungi; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–378.

- Jones, E.B.G.; Pang, K.-L.; Abdel-Wahab, M.A.; Scholz, B.; Hyde, K.D.; Boekhout, T.; Ebel, R.; Rateb, M.E.; Henderson, L.; Sakayaroj, J.; et al. An online resource for marine fungi. Fungal Divers. 2019, 96, 347–433.

- Barghoorn, E.S.; Linder, D.H. Marine Fungi: Their Taxonomy and Biology; WorldCat: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1944.

- Kohlmeyer, J.; Kohlmeyer, E. Marine Mycology; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1979.

- Dix, N.J.; Webster, J. Aquatic Fungi. In Fungal Ecology; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1995; pp. 225–283.

- Zhang, T.; Wang, N.F.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Liu, H.Y.; Yu, L.Y. Diversity and distribution of fungal communities in the marine sediments of Kongsfjorden, Svalbard (High Arctic). Sci. Data 2015, 5, 14524. Available online: www.nature.com/scientificreports/ (accessed on 9 May 2021).

- Jones, E.B.G.; Suetrong, S.; Sakayaroj, J.; Bahkali, A.H.; Abdel-Wahab, M.A.; Boekhout, T.; Pang, K.-L. Classification of marine Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, Blastocladiomycota and Chytridiomycota. Fungal Divers. 2015, 73, 1–72.

- Scholz, B.; Küpper, F.C.; Vyverman, W.; Karsten, U. Effects of eukaryotic pathogens (Chytridiomycota and Oomycota) on marine benthic diatom communities in the Solthörn tidal flat (southern North Sea, Germany). Eur. J. Phycol. 2016, 51, 253–269.

- Marano, A.V.; Gleason, F.H.; Bärlocher, F.; Pires-Zottarelli, C.L.; Lilje, O.; Schmidt, S.K.; Rasconi, S.; Kagami, M.; Barrera, M.D.; Sime-Ngando, T.; et al. Quantitative methods for the analysis of zoosporic fungi. J. Microbiol. Methods 2012, 89, 22–32.

- Johnson, T.W., Jr.; Sparrow, F.K. Fungi in Oceans and Estuaries. Hafner Pub. Co. 1961. Available online: https://www.worldcat.org/title/fungi-in-oceans-and-estuaries-by-tw-johnson-jr-and-fk-sparrow-jr/oclc/876268658 (accessed on 6 September 2021).

- Adl, S.M.; Simpson, A.G.B.; Lane, C.E.; Lukes, J.; Bass, D.; Bowser, S.S.; Brown, M.; Burki, F.; Dunthorn, M.; Hampl, V.; et al. The Revised Classification of Eukaryotes. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2012, 59, 429–514.

- Wijayawardene, N.N.; Hyde, K.D.; Tibpromma, S.; Wanasinghe, D.N.; Thambugala, K.M.; Tian, Q.; Wang, Y.; Fu, L. Towards incorporating asexual fungi in a natural classification: Checklist and notes 2012–2016. Mycosphere 2017, 8, 1457–1555.

- Hyde, K.D.; Chaiwan, N.; Norphanphoun, C.; Boonmee, S.; Camporesi, E.; Chethana, K.W.T.; Dayarathne, M.C.; De Silva, N.I.; Dissanayake, A.J.; Ekanayaka, A.H.; et al. Mycosphere notes 169–224. Mycosphere 2018, 9, 271–430.

- Tedersoo, L.; Sánchez-Ramírez, S.; Kõljalg, U.; Bahram, M.; Döring, M.; Schigel, D.; May, T.; Ryberg, M.; Abarenkov, K. High-level classification of the Fungi and a tool for evolutionary ecological analyses. Fungal Divers. 2018, 90, 135–159.

- Choi, J.; Kim, S.-H. A genome Tree of Life for the Fungi kingdom. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 9391–9396.

- Ibelings, B.W.; De Bruin, A.; Kagami, M.; Rijkeboer, M.; Brehm, M.; Van Donk, E. Host parasite interactions between freshwater phytoplankton and chytrid fungi (chytridiomycota). J. Phycol. 2004, 40, 437–453.

- Wijayawardene, N.N.; Pawłowska, J.; Letcher, P.M.; Kirk, P.M.; Humber, R.A.; Schüßler, A.; Wrzosek, M.; Muszewska, A.; Okrasińska, A.; Istel, Ł.; et al. Notes for genera: Basal clades of Fungi (including Aphelidiomycota, Basidiobolomycota, Blastocladiomycota, Calcarisporiellomycota, Caulochytriomycota, Chytridiomycota, Entomophthoromycota, Glomeromycota, Kickxellomycota, Monoblepharomycota, Mortierellomyc. Fungal Divers. 2018, 92, 43–129.

- Beakes, G.W. Sporulation of Lower Fungi. In The Growing Fungus; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1995; pp. 339–366.

- Trinci, A.P.; Davies, D.R.; Gull, K.; Lawrence, M.I.; Nielsen, B.B.; Rickers, A.; Theodorou, M.K. Anaerobic fungi in herbivorous animals. Mycol. Res. 1994, 98, 129–152.

- Hoffman, Y.; Aflalo, C.; Zarka, A.; Gutman, J.; James, T.Y.; Boussiba, S. Isolation and characterization of a novel chytrid species (phylum Blastocladiomycota), parasitic on the green alga Haematococcus. Mycol. Res. 2008, 112, 70–81.

- Gleason, F.H.; Kagami, M.; Lefevre, E.; Sime-Ngando, T. The ecology of chytrids in aquatic ecosystems: Roles in food web dynamics. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2008, 22, 17–25.

- Medina, E.M.; Robinson, K.A.; Bellingham-Johnstun, K.; Ianiri, G.; Laplante, C.; Fritz-Laylin, L.K.; Buchler, N.E. Genetic transformation of Spizellomyces punctatus, a resource for studying chytrid biology and evolutionary cell biology. eLife 2020, 9, 1–20.

- Frenken, T.; Alacid, E.; Berger, S.A.; Bourne, E.; Gerphagnon, M.; Grossart, H.-P.; Gsell, A.; Ibelings, B.W.; Kagami, M.; Küpper, F.C.; et al. Integrating chytrid fungal parasites into plankton ecology: Research gaps and needs. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 19, 3802–3822.

- Jones, E.B.G. Form and function of fungal spore appendages. Mycoscience 2006, 47, 167–183.

- Amend, A.; Burgaud, G.; Cunliffe, M.; Edgcomb, V.P.; Ettinger, C.L.; Gutiérrez, M.H.; Heitman, J.; Hom, E.F.Y.; Ianiri, G.; Jones, A.C.; et al. Fungi in the Marine Environment: Open Questions and Unsolved Problems. mBio 2019, 10, e01189-18.

- Grossart, H.P.; Van den Wyngaert, S.; Kagami, M.; Wurzbacher, C.; Cunliffe, M.; Rojas-Jimenez, K. Fungi in aquatic ecosystems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 339–354. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30872817/ (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Raghukumar, S. Methods to Study Marine Fungi. In Fungi in Coastal and Oceanic Marine Ecosystems; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 323–343.

- David L. Hawksworth; Robert Lücking; Fungal Diversity Revisited: 2.2 to 3.8 Million Species. Microbiology Spectrum 2017, 5, 79-95, 10.1128/microbiolspec.funk-0052-2016.

- Kerstin Voigt; Timothy Y. James; Paul M. Kirk; André L. C. M. De A. Santiago; Bruce Waldman; Gareth W. Griffith; Minjie Fu; Renate Radek; Jürgen F. H. Strassert; Christian Wurzbacher; et al.Gustavo Henrique JerônimoDavid R. SimmonsKensuke SetoEleni GentekakiVedprakash G. HurdealKevin D. HydeThuong T. T. NguyenHyang Burm Lee Early-diverging fungal phyla: taxonomy, species concept, ecology, distribution, anthropogenic impact, and novel phylogenetic proposals. Fungal Diversity 2021, 109, 59-98, 10.1007/s13225-021-00480-y.

- Kevin D. Hyde; Rajesh Jeewon; Yi-Jyun Chen; Chitrabhanu S. Bhunjun; Mark S. Calabon; Hong-Bo Jiang; Chuan-Gen Lin; Chada Norphanphoun; Phongeun Sysouphanthong; Dhandevi Pem; et al.Saowaluck TibprommaQian ZhangMingkwan DoilomRuvishika S. JayawardenaJian-Kui LiuSajeewa S. N. MaharachchikumburaChayanard PhukhamsakdaRungtiwa PhookamsakAbdullah M. Al-SadiNaritsada ThongklangYong WangYusufjon GafforovE. B. Gareth JonesSaisamorn Lumyong The numbers of fungi: is the descriptive curve flattening?. Fungal Diversity 2020, 103, 219-271, 10.1007/s13225-020-00458-2.

- Wurzbacher Christian; Kerr Janice; Grossart Hans-Peter; Aquatic Fungi. The Dynamical Processes of Biodiversity - Case Studies of Evolution and Spatial Distribution 2011, -, 227–257, 10.5772/23029.

- Télesphore Sime - Ngando; Phytoplankton Chytridiomycosis: Fungal Parasites of Phytoplankton and Their Imprints on the Food Web Dynamics. Frontiers in Microbiology 2012, 3, 361, 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00361.

- Kevin D Lafferty; Parasites in Marine Food Webs. Bulletin of Marine Science 2013, 89, 123-134, 10.5343/bms.2011.1124.

- D. J. Marcogliese; Parasites: Small Players with Crucial Roles in the Ecological Theater. EcoHealth 2004, 1, 151-164, 10.1007/s10393-004-0028-3.

- Ross M. Thompson; Kim N. Mouritsen; Robert Poulin; Importance of parasites and their life cycle characteristics in determining the structure of a large marine food web. Journal of Animal Ecology 2004, 74, 77-85, 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2004.00899.x.

- Jennifer A. Dunne; Kevin D. Lafferty; Andrew P. Dobson; Ryan Hechinger; Armand M. Kuris; Neo Martinez; John P. McLaughlin; Kim N. Mouritsen; Robert Poulin; Karsten Reise; et al.Daniel B. StoufferDavid W. ThieltgesRichard WilliamsClaus Dieter Zander Parasites Affect Food Web Structure Primarily through Increased Diversity and Complexity. PLoS Biology 2013, 11, e1001579, 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001579.

- Serena Rasconi; M Jobard; T Sime-Ngando; Parasitic fungi of phytoplankton: ecological roles and implications for microbial food webs. Aquatic Microbial Ecology 2011, 62, 123-137, 10.3354/ame01448.

- Serena Rasconi; Boutheina Egrami; Nathalie Niquil; Marlã¨ne Jobard; Télesphore Sime-Ngando; Parasitic chytrids sustain zooplankton growth during inedible algal bloom. Frontiers in Microbiology 2014, 5, 229, 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00229.

- Ramsy Agha; Manja Saebelfeld; Christin Manthey; Thomas Rohrlack; Justyna Wolinska; Chytrid parasitism facilitates trophic transfer between bloom-forming cyanobacteria and zooplankton (Daphnia). Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 35039, 10.1038/srep35039.

- Mélanie Gerphagnon; Ramsy Agha; Dominik Martin-Creuzburg; Alexandre Bec; Fanny Perriere; Cecilia Rad Menéndez; Claire M.M. Gachon; Justyna Wolinska; Comparison of sterol and fatty acid profiles of chytrids and their hosts reveals trophic upgrading of nutritionally inadequate phytoplankton by fungal parasites. Environmental Microbiology 2018, 21, 949-958, 10.1111/1462-2920.14489.

- Virginia Sánchez Barranco; Marcel T. J. Van Der Meer; Maiko Kagami; Silke Van Den Wyngaert; Dedmer B. Van De Waal; Ellen Van Donk; Alena S. Gsell; Trophic position, elemental ratios and nitrogen transfer in a planktonic host–parasite–consumer food chain including a fungal parasite. Oecologia 2020, 194, 541-554, 10.1007/s00442-020-04721-w.

- Serena Rasconi; Robert Ptacnik; Stefanie Danner; Silke Van Den Wyngaert; Thomas Rohrlack; Matthias Pilecky; Martin J. Kainz; Parasitic Chytrids Upgrade and Convey Primary Produced Carbon During Inedible Algae Proliferation. Protist 2020, 171, 125768, 10.1016/j.protis.2020.125768.

- Peter J. Hudson; Andrew P. Dobson; Kevin D. Lafferty; Is a healthy ecosystem one that is rich in parasites?. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 2006, 21, 381-385, 10.1016/j.tree.2006.04.007.

- Hans-Peter Grossart; Keilor Rojas-Jimenez; Aquatic fungi: targeting the forgotten in microbial ecology. Current Opinion in Microbiology 2016, 31, 140-145, 10.1016/j.mib.2016.03.016.

- Sergey A. Karpov; Maria A. Mamkaeva; Vladimir V. Aleoshin; Elena Enassonova; Osu Elilje; Frank H. Gleason; Morphology, phylogeny, and ecology of the aphelids (Aphelidea, Opisthokonta) and proposal for the new superphylum Opisthosporidia. Frontiers in Microbiology 2014, 5, 112, 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00112.

- Timothy Y. James; Frank Kauff; Conrad L. Schoch; P. Brandon Matheny; Valérie Hofstetter; Cymon Cox; Gail Celio; Cécile Gueidan; Emily Fraker; Jolanta Miadlikowska; et al.H. Thorsten LumbschAlexandra RauhutValérie ReebA. Elizabeth ArnoldAnja AmtoftJason StajichKentaro HosakaGi-Ho SungDesiree JohnsonBen O’RourkeMichael CrockettManfred BinderJudd M. CurtisJason C. SlotZheng WangAndrew W. WilsonArthur SchüsslerJoyce E. LongcoreKerry O’DonnellSharon Mozley-StandridgeDavid PorterPeter M. LetcherMartha J. PowellJohn W. TaylorMerlin M. WhiteGareth GriffithDavid R. DaviesRichard A. HumberJoseph B. MortonJunta SugiyamaAmy Y. RossmanJack D. RogersDon H. PfisterDavid HewittKaren HansenSarah HambletonRobert A. ShoemakerJan KohlmeyerBrigitte Volkmann-KohlmeyerRobert A. SpottsMaryna SerdaniPedro W. CrousKaren W. HughesKenji MatsuuraEwald LangerGitta LangerWendy A. UntereinerRobert LückingBurkhard BüdelDavid M. GeiserAndré AptrootPaul DiederichImke SchmittMatthias SchultzRebecca YahrDavid S. HibbettFrançois LutzoniDavid J. McLaughlinJoseph W. SpataforaRytas Vilgalys Reconstructing the early evolution of Fungi using a six-gene phylogeny. Nature 2006, 443, 818-822, 10.1038/nature05110.

- Meredith D. M. Jones; Thomas Richards; David L. Hawksworth; David Bass; Validation and justification of the phylum name Cryptomycota phyl. nov.. IMA Fungus 2011, 2, 173-175, 10.5598/imafungus.2011.02.02.08.

- Timothy Y. James; Mary L. Berbee; No jacket required - new fungal lineage defies dress code. BioEssays 2011, 34, 94-102, 10.1002/bies.201100110.

- Sergey A. Karpov; Guifré Torruella; David Moreira; Maria A. Mamkaeva; Purificación López‐García; Molecular Phylogeny of Paraphelidium letcheri sp. nov. (Aphelida, Opisthosporidia).. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology 2016, 64, 573-578, 10.1111/jeu.12389.

- Peter M. Letcher; Salvador Lopez; Robert Schmieder; Philip A. Lee; Craig Behnke; Martha J. Powell; Robert C. McBride; Characterization of Amoeboaphelidium protococcarum, an Algal Parasite New to the Cryptomycota Isolated from an Outdoor Algal Pond Used for the Production of Biofuel. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56232, 10.1371/journal.pone.0056232.

- Leho Tedersoo; Mohammad Bahram; Rasmus Puusepp; Henrik Nilsson; Timothy Y. James; Novel soil-inhabiting clades fill gaps in the fungal tree of life. Microbiome 2017, 5, 1-10, 10.1186/s40168-017-0259-5.

- Brandon T. Hassett; Marco Thines; Anthony Buaya; Sebastian Ploch; Rolf Gradinger; A glimpse into the biogeography, seasonality, and ecological functions of arctic marine Oomycota. IMA Fungus 2019, 10, 1-10, 10.1186/s43008-019-0006-6.

- Kevin D. Hyde; E.B. Gareth Jones; Eduardo Leaño; Stephen B. Pointing; Asha D. Poonyth; Lilian L.P. Vrijmoed; Role of fungi in marine ecosystems. Biodiversity and Conservation 1998, 7, 1147-1161, 10.1023/a:1008823515157.

- Miguel Ángel Naranjo-Ortiz; Toni Gabaldón; Fungal evolution: diversity, taxonomy and phylogeny of the Fungi. Biological Reviews 2019, 94, 2101-2137, 10.1111/brv.12550.

- Peter M. Letcher; Martha J. Powell; A taxonomic summary and revision of Rozella (Cryptomycota). IMA Fungus 2018, 9, 383-399, 10.5598/imafungus.2018.09.02.09.

- Vedprakash G. Hurdeal; Eleni Gentekaki; Kevin D. Hyde; Rajesh Jeewon; Where are the basal fungi? Current status on diversity, ecology, evolution, and taxonomy. Biologia 2020, 76, 421-440, 10.2478/s11756-020-00642-4.

- Daniele Corsaro; Julia Walochnik; Danielle Venditti; Karl-Dieter Müller; Bärbel Hauröder; Rolf Michel; Rediscovery of Nucleophaga amoebae, a novel member of the Rozellomycota. Parasitology Research 2014, 113, 4491-4498, 10.1007/s00436-014-4138-8.

- Abraham A. Held; Rozella andRozellopsis: Naked endoparasitic fungi which dress-up as their hosts. The Botanical Review 1981, 47, 451-515, 10.1007/bf02860539.

- Frank H. Gleason; Laura Carney; Osu Lilje; Sally L. Glockling; Ecological potentials of species of Rozella (Cryptomycota). Fungal Ecology 2012, 5, 651-656, 10.1016/j.funeco.2012.05.003.

- D. J. S. Barr; Chytridiomycota. Systematics and Evolution 2001, -, 93-112, 10.1007/978-3-662-10376-0_5.

- Timothy Y. James; Peter M. Letcher; Joyce E. Longcore; Sharon E. Mozley-Standridge; David Porter; Martha J. Powell; Gareth Griffith; Rytas Vilgalys; A molecular phylogeny of the flagellated fungi (Chytridiomycota) and description of a new phylum (Blastocladiomycota). Mycologia 2006, 98, 860-871, 10.3852/mycologia.98.6.860.

- Enrique Lara; David Moreira; Purificación López-García; The Environmental Clade LKM11 and Rozella Form the Deepest Branching Clade of Fungi. Protist 2010, 161, 116-121, 10.1016/j.protis.2009.06.005.

- Hans-Peter Grossart; Christian Wurzbacher; Timothy Y. James; Maiko Kagami; Discovery of dark matter fungi in aquatic ecosystems demands a reappraisal of the phylogeny and ecology of zoosporic fungi. Fungal Ecology 2016, 19, 28-38, 10.1016/j.funeco.2015.06.004.

- Christian Wurzbacher; Norman Warthmann; Elizabeth Bourne; Katrin Attermeyer; Martin Allgaier; Jeff R. Powell; Harald Detering; Susan Mbedi; Hans-Peter Grossart; Michael T. Monaghan; et al. High habitat-specificity in fungal communities in oligo-mesotrophic, temperate Lake Stechlin (North-East Germany). MycoKeys 2016, 16, 17-44, 10.3897/mycokeys.16.9646.

- Keilor Rojas-Jimenez; Christian Wurzbacher; Elizabeth Bourne; Amy Chiuchiolo; John C. Priscu; Hans-Peter Grossart; Early diverging lineages within Cryptomycota and Chytridiomycota dominate the fungal communities in ice-covered lakes of the McMurdo Dry Valleys, Antarctica. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 15348, 10.1038/s41598-017-15598-w.

- Thomas A. Richards; Guy Leonard; Frédéric Mahé; Javier del Campo; Sarah Romac; Meredith D. M. Jones; Finlay Maguire; Micah Dunthorn; Colomban De Vargas; Ramon Massana; et al.Aurelie Chambouvet Molecular diversity and distribution of marine fungi across 130 European environmental samples. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2015, 282, 20152243, 10.1098/rspb.2015.2243.

- Brandon T Hassett; Rolf R Gradinger; Chytrids dominate arctic marine fungal communities. Environmental Microbiology 2016, 18, 2001-2009, 10.1111/1462-2920.13216.

- Yaping Wang; Xiaohong Guo; Pengfei Zheng; Songbao Zou; Guihao Li; Jun Gong; Distinct seasonality of chytrid-dominated benthic fungal communities in the neritic oceans (Bohai Sea and North Yellow Sea). Fungal Ecology 2017, 30, 55-66, 10.1016/j.funeco.2017.08.008.

- Meredith D. M. Jones; Irene Forn; Catarina Gadelha; Martin J. Egan; David Bass; Ramon Massana; Thomas A. Richards; Discovery of novel intermediate forms redefines the fungal tree of life. Nature 2011, 474, 200-203, 10.1038/nature09984.

- Timothy Y. James; Jason E. Stajich; Chris Todd Hittinger; Antonis Rokas; Toward a Fully Resolved Fungal Tree of Life. Annual Review of Microbiology 2020, 74, 291-313, 10.1146/annurev-micro-022020-051835.

- Taylor Priest; Bernhard Fuchs; Rudolf Amann; Marlis Reich; Diversity and biomass dynamics of unicellular marine fungi during a spring phytoplankton bloom. Environmental Microbiology 2020, 23, 448-463, 10.1111/1462-2920.15331.

- Alex M. Ardila-Garcia; Nandini Raghuram; Panela Sihota; Naomi M. Fast; Microsporidian Diversity in Soil, Sand, and Compost of the Pacific Northwest. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology 2013, 60, 601-608, 10.1111/jeu.12066.

- Ka-Lai Pang; Brandon T. Hassett; Ami Shaumi; Sheng-Yu Guo; Jariya Sakayaroj; Michael Wai-Lun Chiang; Chien-Hui Yang; E.B. Gareth Jones; Pathogenic fungi of marine animals: A taxonomic perspective. Fungal Biology Reviews 2021, 38, 92-106, 10.1016/j.fbr.2021.03.008.

- Eunji Park; Robert Poulin; Revisiting the phylogeny of microsporidia. International Journal for Parasitology 2021, 51, 855-864, 10.1016/j.ijpara.2021.02.005.

- Brandon M. Murareanu; Ronesh Sukhdeo; Rui Qu; Jason Jiang; Aaron W. Reinke; Generation of a Microsporidia Species Attribute Database and Analysis of the Extensive Ecological and Phenotypic Diversity of Microsporidia. mBio 2021, 12, e0149021, 10.1128/mbio.01490-21.

- André M. Comeau; Warwick Vincent; Louis Bernier; Connie Lovejoy; Novel chytrid lineages dominate fungal sequences in diverse marine and freshwater habitats. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 30120, 10.1038/srep30120.

- Kensuke Seto; Maiko Kagami; Yousuke Degawa; Phylogenetic Position of Parasitic Chytrids on Diatoms: Characterization of a Novel Clade in Chytridiomycota. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology 2016, 64, 383-393, 10.1111/jeu.12373.

- Carol A. Shearer; Enrique Descals; Brigitte Kohlmeyer; Jan Kohlmeyer; Ludmila Marvanová; David Padgett; David Porter; Huzefa A. Raja; John P. Schmit; Holly A. Thorton; et al.Hermann Voglymayr Fungal biodiversity in aquatic habitats. Biodiversity and Conservation 2006, 16, 49-67, 10.1007/s10531-006-9120-z.

- Jason E. Stajich; Mary L. Berbee; Meredith Blackwell; David S. Hibbett; Timothy Y. James; Joseph W. Spatafora; John W. Taylor; The Fungi. Current Biology 2009, 19, R840-R845, 10.1016/j.cub.2009.07.004.

- Silke Van Den Wyngaert; Kensuke Seto; Keilor Rojas-Jimenez; Maiko Kagami; Hans-Peter Grossart; A New Parasitic Chytrid, Staurastromyces oculus (Rhizophydiales, Staurastromycetaceae fam. nov.), Infecting the Freshwater Desmid Staurastrum sp.. Protist 2017, 168, 392-407, 10.1016/j.protis.2017.05.001.

- Birthe Zäncker; Michael Cunliffe; Anja Engel; Eukaryotic community composition in the sea surface microlayer across an east–west transect in the Mediterranean Sea. Biogeosciences 2021, 18, 2107-2118, 10.5194/bg-18-2107-2021.

- Joe Taylor; Michael Cunliffe; Multi-year assessment of coastal planktonic fungi reveals environmental drivers of diversity and abundance. The ISME Journal 2016, 10, 2118-2128, 10.1038/ismej.2016.24.

- Yanyan Yang; Stefanos Banos; Gunnar Gerdts; Antje Wichels; Marlis Reich; Mycoplankton Biome Structure and Assemblage Processes Differ Along a Transect From the Elbe River Down to the River Plume and the Adjacent Marine Waters. Frontiers in Microbiology 2021, 12, 1-15, 10.3389/fmicb.2021.640469.

- Laura Käse; Katja Metfies; Stefan Neuhaus; Maarten Boersma; Karen Helen Wiltshire; Alexandra Claudia Kraberg; Host-parasitoid associations in marine planktonic time series: Can metabarcoding help reveal them?. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0244817, 10.1371/journal.pone.0244817.

- Stefanos Banos; Deisy Morselli Gysi; Tim Richter-Heitmann; Frank Oliver Glöckner; Maarten Boersma; Karen H. Wiltshire; Gunnar Gerdts; Antje Wichels; Marlis Reich; Seasonal Dynamics of Pelagic Mycoplanktonic Communities: Interplay of Taxon Abundance, Temporal Occurrence, and Biotic Interactions. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 11, 1305, 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01305.

- James P. Amon; Rhizophydium Littoreum: A Chytrid from Siphonaceous Marine Algae—An Ultrastructural Examination. Mycologia 1984, 76, 132-139, 10.1080/00275514.1984.12023817.

- Pi Nyvall; Marianne Pedersen; Joyce E. Longcore; THALASSOCHYTRIUM GRACILARIOPSIDIS (CHYTRIDIOMYCOTA), GEN. ET SP. NOV., ENDOSYMBIOTIC IN GRACILARIOPSIS SP. (RHODOPHYCEAE). Journal of Phycology 1999, 35, 176-185, 10.1046/j.1529-8817.1999.3510176.x.

- Frithjof C. Küpper; Dieter G. Müller; Massive occurrence of the heterokont and fungal parasites Anisolpidium, Eurychasma and Chytridium in Pylaiella littoralis (Ectocarpales, Phaeophyceae). Nova Hedwigia 1999, 69, 381-389, 10.1127/nova.hedwigia/69/1999/381.

- P. S. Salomon; I. Imai; Pathogens of Harmful Microalgae. Ecological Studies 2006, -, 271-282, 10.1007/978-3-540-32210-8_21.

- Louis A. Hanic; Satoshi Sekimoto; Stephen S. Bates; Oomycete and chytrid infections of the marine diatom Pseudo-nitzschia pungens (Bacillariophyceae) from Prince Edward Island, Canada. Botany 2009, 87, 1096-1105, 10.1139/b09-070.

- Frank H. Gleason; Frithjof C. Küpper; James P. Amon; Kathryn Picard; Claire M. M. Gachon; Agostina V. Marano; Télesphore Sime-Ngando; Osu Lilje; Zoosporic true fungi in marine ecosystems: a review. Marine and Freshwater Research 2011, 62, 383-393, 10.1071/mf10294.

- Hilda M. Canter; J.W.G. Lund; Studies on plankton parasites: II. The parasitism of diatoms with special reference to lakes in the English Lake District. Transactions of the British Mycological Society 1953, 36, 13-37, 10.1016/s0007-1536(53)80038-0.

- Hilda M. Canter; Studies on British Chytrids. XXIX. A taxonomic revision of certain fungi found on the diatom Asterionella. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 1969, 62, 267-278, 10.1111/j.1095-8339.1969.tb01970.x.

- C. S. Reynolds; The seasonal periodicity of planktonic diatoms in a shallow eutrophic lake. Freshwater Biology 1973, 3, 89-110, 10.1111/j.1365-2427.1973.tb00065.x.

- Ellen Van Donk; J. Ringelberg; The effect of fungal parasitism on the succession of diatoms in Lake Maarsseveen I (The Netherlands). Freshwater Biology 1983, 13, 241-251, 10.1111/j.1365-2427.1983.tb00674.x.

- Davis Laundon; Thomas Mock; Glen Wheeler; Michael Cunliffe; Healthy herds in the phytoplankton: the benefit of selective parasitism. The ISME Journal 2021, 15, 2163-2166, 10.1038/s41396-021-00936-8.

- Cordelia Roberts; Ro Allen; Kimberley E. Bird; Michael Cunliffe; Chytrid fungi shape bacterial communities on model particulate organic matter. Biology Letters 2020, 16, 20200368, 10.1098/rsbl.2020.0368.

- David Gotelli; Lagenisma Coscinodisci, A Parasite of the Marine Diatom Coscinodiscus Occurring in the Puget Sound, Washington. Mycologia 1971, 63, 171-174, 10.1080/00275514.1971.12019095.

- Frederick K. Sparrow; Zoosporic marine fungi from the Pacific Northwest (U.S.A.). Archives of Microbiology 1969, 66, 129-146, 10.1007/bf00410220.

- Domenico Benvenuto; Marta Giovannetti; Alessandra Ciccozzi; Silvia Spoto; Silvia Angeletti; Massimo Ciccozzi; The 2019‐new coronavirus epidemic: Evidence for virus evolution. Journal of Medical Virology 2020, 92, 455-459, 10.1002/jmv.25688.

- Ted Ozersky; Teofil Nakov; Stephanie E. Hampton; Nicholas L. Rodenhouse; Kara H. Woo; Kirill Shchapov; Katie Wright; Helena V. Pislegina; Lyubov R. Izmest'Eva; Eugene A. Silow; et al.Maxim A. TimofeevMarianne V. Moore Hot and sick? Impacts of warming and a parasite on the dominant zooplankter of Lake Baikal. Limnology and Oceanography 2020, 65, 2772-2786, 10.1002/lno.11550.

- Anthony T. Buaya; Sebastian Ploch; Alexandra Kraberg; Marco Thines; Phylogeny and cultivation of the holocarpic oomycete Diatomophthora perforans comb. nov., an endoparasitoid of marine diatoms. Mycological Progress 2020, 19, 441-454, 10.1007/s11557-020-01569-5.

- Michael Schweikert; Eberhard Schnepf; Pseudaphelidium drebesii, genet specnov(incerta sedis), a Parasite of the Marine Centric Diatom Thalassiosira punctigera. Archiv für Protistenkunde 1996, 147, 11-17, 10.1016/s0003-9365(96)80004-2.

- Wei Li; Tianyu Zhang; Xuexi Tang; Bingyao Wang; Oomycetes and fungi: important parasites on marine algae. Acta Oceanologica Sinica 2010, 29, 74-81, 10.1007/s13131-010-0065-4.

- C Raghukumar; Fungal parasites of marine algae from Mandapam (South India). Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 1987, 3, 137-145, 10.3354/dao003137.

- Bettina Scholz; Wim Vyverman; Frithjof C. Küpper; Halldór G. Ólafsson; Ulf Karsten; Effects of environmental parameters on chytrid infection prevalence of four marine diatoms: a laboratory case study. Botanica Marina 2017, 60, 419-431, 10.1515/bot-2016-0105.

- Peter M. Letcher; Martha J. Powell; Perry F. Churchill; James G. Chambers; Ultrastructural and molecular phylogenetic delineation of a new order, the Rhizophydiales (Chytridiomycota). Mycological Research 2006, 110, 898-915, 10.1016/j.mycres.2006.06.011.

- Jeffrey D. Shields; Rhizophydium littoreum on the Eggs of Cancer anthonyi: Parasite or Saprobe?. The Biological Bulletin 1990, 179, 201-206, 10.2307/1541770.

- J. M. Krauhs; J. L. Long; P. S. Baur; Spores of a New Microsporidan Species Parasitizing Molluscan Neurons. The Journal of Protozoology 1979, 26, 43-46, 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1979.tb02729.x.

- Amir Sapir; Adler R. Dillman; Stephanie A. Connon; Benjamin M. Grupe; Jeroen Ingels; Manuel Mundo-Ocampo; Lisa A. Levin; James G. Baldwin; Victoria J. Orphan; Paul W. Sternberg; et al. Microsporidia-nematode associations in methane seeps reveal basal fungal parasitism in the deep sea. Frontiers in Microbiology 2014, 5, 43, 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00043.

- J. Leiro; M. Ortega; R. Iglesias; J. Estévez; M. L. Sanmartín; Pleistophora finisterrensis n. sp., a microsporidian parasite of blue whiting Micromesistius poutassou. Systematic Parasitology 1996, 34, 163-170, 10.1007/bf00009384.

- Elizabeth U. Canning; J. P. Nicholas; Genus Pleistophora (Phylum Microspora): redescription of the type species, Pleistophora typicalis Gurley, 1893 and ultrastructural characterization of the genus. Journal of Fish Diseases 1980, 3, 317-338, 10.1111/j.1365-2761.1980.tb00402.x.

- N. Faye; B. S. Toguebaye; G. Bouix; Ultrastructure and development of Pleistophora senegalensis sp. nov. (Protozoa, Microspora) from the gilt-head sea bream, Sparus aurata L. (Teleost, Sparidae) from the coast of Senegal. Journal of Fish Diseases 1990, 13, 179-192, 10.1111/j.1365-2761.1990.tb00773.x.

- Amanda M. V. Brown; Martin L. Adamson; Phylogenetic Distance of Thelohania butleri (Microsporidia; Thelohaniidae), a Parasite of the Smooth Pink Shrimp Pandalus jordani, from its Congeners Suggests Need for Major Revision of the Genus Thelohania Henneguy, 1892. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology 2006, 53, 445-455, 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2006.00128.x.

- C Azevedo; E U Canning; Ultrastructure of a microsporidian hyperparasite, Unikaryon legeri (Microsporida), of trematode larvae.. Journal of Parasitology 1987, 73, 214.

- Urban Tillmann; Karl-Jürgen Hesse; Anette Tillmann; Large-scale parasitic infection of diatoms in the Northfrisian Wadden Sea. Journal of Sea Research 1999, 42, 255-261, 10.1016/s1385-1101(99)00029-5.

- Anthony T. Buaya; Sebastian Ploch; Louis Hanic; Bora Nam; Lisa Nigrelli; Alexandra Kraberg; Marco Thines; Phylogeny of Miracula helgolandica gen. et sp. nov. and Olpidiopsis drebesii sp. nov., two basal oomycete parasitoids of marine diatoms, with notes on the taxonomy of Ectrogella-like species. Mycological Progress 2017, 16, 1041-1050, 10.1007/s11557-017-1345-6.

- A.T. Buaya; M. Thines; Diatomophthoraceae – a new family of olpidiopsis-like diatom parasitoids largely unrelated to Ectrogella. Fungal Systematics and Evolution 2020, 5, 113-118, 10.3114/fuse.2020.05.06.

- Andrea Garvetto; Elisabeth Nézan; Yacine Badis; Gwenael Bilien; Paola Arce; Eileen Bresnan; Claire M. M. Gachon; Raffaele Siano; Novel Widespread Marine Oomycetes Parasitising Diatoms, Including the Toxic Genus Pseudo-nitzschia: Genetic, Morphological, and Ecological Characterisation. Frontiers in Microbiology 2018, 9, 2918, 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02918.

- Marco Thines; Bora Nam; Lisa Nigrelli; Gordon Beakes; Alexandra Kraberg; The diatom parasite Lagenisma coscinodisci (Lagenismatales, Oomycota) is an early diverging lineage of the Saprolegniomycetes. Mycological Progress 2015, 14, 1-7, 10.1007/s11557-015-1099-y.

- Eberhard Schnepf; G. Deichgräber; Gerhard Drebes; Development and ultrastructure of the marine, parasitic oomycete, Lagenisma coscinodisci (Lagenidiales): encystment of primary zoospores. Canadian Journal of Botany 1978, 56, 1309-1314, 10.1139/b78-148.

- C. M. Pueschel; J. P. Van Der Meer; Ultrastructure of the fungus Petersenia palmariae (Oomycetes) parasitic on the alga Palmaria mollis (Rhodophyceae). Canadian Journal of Botany 1985, 63, 409-418, 10.1139/b85-049.

- T. W. Johnson; Rozella marina in Chytridium polysiphoniae from Icelandic Waters. Mycologia 1966, 58, 490, 10.2307/3756929.

- Arnout De Bruin; Bastiaan Willem Ibelings; Machteld Rijkeboer; Michaela Brehm; Ellen van Donk; GENETIC VARIATION IN ASTERIONELLA FORMOSA (BACILLARIOPHYCEAE): IS IT LINKED TO FREQUENT EPIDEMICS OF HOST-SPECIFIC PARASITIC FUNGI?1. Journal of Phycology 2004, 40, 823-830, 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2004.04006.x.

- Maiko Kagami; Arnout de Bruin; Bas W. Ibelings; Ellen Van Donk; Parasitic chytrids: their effects on phytoplankton communities and food-web dynamics. Hydrobiologia 2007, 578, 113-129, 10.1007/s10750-006-0438-z.

- A. V. Koehler; Y. P. Springer; H. S. Randhawa; T. L. F. Leung; D. B. Keeney; R. Poulin; Genetic and phenotypic influences on clone-level success and host specialization in a generalist parasite. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 2011, 25, 66-79, 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02402.x.

- Lisa K. Muehlstein; James P. Amon; Deborah L. Leffler; Chemotaxis in the Marine Fungus Rhizophydium littoreum. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 1988, 54, 1668-1672, 10.1128/aem.54.7.1668-1672.1988.

- Yile Tao; Justyna Wolinska; Franz Hölker; Ramsy Agha; Light intensity and spectral distribution affect chytrid infection of cyanobacteria via modulation of host fitness. Parasitology 2020, 147, 1206-1215, 10.1017/s0031182020000931.

- K Yoneya; T Miki; Sv Den Wyngaert; Hp Grossart; M Kagami; Non-random patterns of chytrid infections on phytoplankton host cells: mathematical and chemical ecology approaches. Aquatic Microbial Ecology 2021, 87, 1-15, 10.3354/ame01966.

- Hanna Schenk; Hinrich Schulenburg; Arne Traulsen; How long do Red Queen dynamics survive under genetic drift? A comparative analysis of evolutionary and eco-evolutionary models. null 2018, 20, 490201, 10.1101/490201.

- Franziska S. Brunner; Jaime M. Anaya-Rojas; Blake Matthews; Christophe Eizaguirre; Experimental evidence that parasites drive eco-evolutionary feedbacks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114, 3678-3683, 10.1073/pnas.1619147114.

- Pierre Horwitz; Bruce A. Wilcox; Parasites, ecosystems and sustainability: an ecological and complex systems perspective. International Journal for Parasitology 2005, 35, 725-732, 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.03.002.

- Samuel R. Fleischer; Daniel I. Bolnick; Sebastian J. Schreiber; Sick of eating: Eco‐evo‐immuno dynamics of predators and their trophically acquired parasites. Evolution 2021, 75, 2842-2856, 10.1111/evo.14353.

- Silke Van Den Wyngaert; Keilor Rojas-Jimenez; Kensuke Seto; Maiko Kagami; Hans-Peter Grossart; Diversity and Hidden Host Specificity of Chytrids Infecting Colonial Volvocacean Algae. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology 2018, 65, 870-881, 10.1111/jeu.12632.

- Ramon Massana; Angélique Gobet; Stéphane Audic; David Bass; Lucie Bittner; Christophe Boutte; Aurelie Chambouvet; Richard Christen; Jean-Michel Claverie; Johan Decelle; et al.John DolanMicah DunthornBente EdvardsenIrene FornDominik ForsterLaure GuillouOlivier JaillonWiebe KooistraRamiro LogaresFrédéric MahéFabrice NotHiroyuki OgataJan PawlowskiMassimo Ciro PerniceIan ProbertSarah RomacThomas RichardsSebastien SantiniKamran Shalchian-TabriziRaffaele SianoNathalie SimonThorsten StoeckDaniel VaulotAdriana ZingoneColomban De Vargas Marine protist diversity in European coastal waters and sediments as revealed by high-throughput sequencing. Environmental Microbiology 2015, 17, 4035-4049, 10.1111/1462-2920.12955.

- Christian Wurzbacher; Ellen Larsson; Johan Bengtsson‐Palme; Silke Van Den Wyngaert; Sten Svantesson; Erik Kristiansson; Maiko Kagami; R. Henrik Nilsson; Introducing ribosomal tandem repeat barcoding for fungi. Molecular Ecology Resources 2018, 19, 118-127, 10.1111/1755-0998.12944.

- Felix Heeger; Elizabeth C. Bourne; Christiane Baschien; Andrey Yurkov; Boyke Bunk; Cathrin Spröer; Jörg Overmann; Camila J. Mazzoni; Michael T. Monaghan; Long-read DNA metabarcoding of ribosomal RNA in the analysis of fungi from aquatic environments. Molecular Ecology Resources 2018, 18, 1500-1514, 10.1111/1755-0998.12937.

- Peter M. Letcher; Carlos G. Vélez; María Eugenia Barrantes; Martha J. Powell; Perry F. Churchill; William S. Wakefield; Ultrastructural and molecular analyses of Rhizophydiales (Chytridiomycota) isolates from North America and Argentina. Mycological Research 2008, 112, 759-782, 10.1016/j.mycres.2008.01.025.

- Ellen Van Donk; The Role of Fungal Parasites in Phytoplankton Succession. Brock/Springer Series in Contemporary Bioscience 1989, -, 171-194, 10.1007/978-3-642-74890-5_5.

- Takeshi Miki; Gaku Takimoto; Maiko Kagami; Roles of parasitic fungi in aquatic food webs: a theoretical approach. Freshwater Biology 2011, 56, 1173-1183, 10.1111/j.1365-2427.2010.02562.x.

- Matilda Haraldsson; Mélanie Gerphagnon; Pauline Bazin; Jonathan Colombet; Samuele Tecchio; Télesphore Sime-Ngando; Nathalie Niquil; Microbial parasites make cyanobacteria blooms less of a trophic dead end than commonly assumed. The ISME Journal 2018, 12, 1008-1020, 10.1038/s41396-018-0045-9.

- Maiko Ekagami; Takeshi Miki; Gaku Etakimoto; Mycoloop: chytrids in aquatic food webs. Frontiers in Microbiology 2014, 5, 166, 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00166.

- Boutheina Grami; Serena Rasconi; Nathalie Niquil; Marlène Jobard; Blanche Saint-Béat; Télesphore Sime-Ngando; Functional Effects of Parasites on Food Web Properties during the Spring Diatom Bloom in Lake Pavin: A Linear Inverse Modeling Analysis. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e23273, 10.1371/journal.pone.0023273.

- Michael Danger; Mark O. Gessner; Felix Bärlocher; Ecological stoichiometry of aquatic fungi: current knowledge and perspectives. Fungal Ecology 2016, 19, 100-111, 10.1016/j.funeco.2015.09.004.

- Yukiko Senga; Shiori Yabe; Takaki Nakamura; Maiko Kagami; Influence of parasitic chytrids on the quantity and quality of algal dissolved organic matter (AOM). Water Research 2018, 145, 346-353, 10.1016/j.watres.2018.08.037.

- Jenny Fabian; Sanja Zlatanović; Michael Mutz; Katrin Premke; Fungal–bacterial dynamics and their contribution to terrigenous carbon turnover in relation to organic matter quality. The ISME Journal 2016, 11, 415-425, 10.1038/ismej.2016.131.

- Isabell Klawonn; Silke Van Den Wyngaert; Alma E. Parada; Nestor Arandia-Gorostidi; Martin J. Whitehouse; Hans-Peter Grossart; Anne E. Dekas; Characterizing the “fungal shunt”: Parasitic fungi on diatoms affect carbon flow and bacterial communities in aquatic microbial food webs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, 118, e210222511, 10.1073/pnas.2102225118.

- Susumu Honjo; Timothy Eglinton; Craig Taylor; Kevin Ulmer; Stefan Sievert; Astrid Bracher; Christopher German; Virginia Edgcomb; Roger Francois; M. Débora Iglesias-Rodriguez; et al.Benjamin Van MooyDaniel Rapeta Understanding the Role of the Biological Pump in the Global Carbon Cycle: An Imperative for Ocean Science. Oceanography 2014, 27, 10-16, 10.5670/oceanog.2014.78.

- Hugh Ducklow; Deborah Steinberg; Ken Buesseler; Upper Ocean Carbon Export and the Biological Pump. Oceanography 2001, 14, 50-58, 10.5670/oceanog.2001.06.

- Luca Polimene; Sevrine Sailley; Darren Clark; Aditee Mitra; J Icarus Allen; Biological or microbial carbon pump? The role of phytoplankton stoichiometry in ocean carbon sequestration. Journal of Plankton Research 2016, 39, 180-186, 10.1093/plankt/fbw091.

- U Passow; Production of transparent exopolymer particles (TEP) by phyto- and bacterioplankton. Marine Ecology Progress Series 2002, 236, 1-12, 10.3354/meps236001.

- A Engel; B Delille; S Jacquet; U Riebesell; E Rochelle-Newall; A Terbrüggen; I Zondervan; Transparent exopolymer particles and dissolved organic carbon production by Emiliania huxleyi exposed to different CO2 concentrations: a mesocosm experiment. Aquatic Microbial Ecology 2004, 34, 93-104, 10.3354/ame034093.

- Anja Engel; Silke Thoms; Ulf Riebesell; Emma Rochelle-Newall; Ingrid Zondervan; Polysaccharide aggregation as a potential sink of marine dissolved organic carbon. Nature 2004, 428, 929-932, 10.1038/nature02453.

- Ramsy Agha; Alina Gross; Melanie Gerphagnon; Thomas Rohrlack; Justyna Wolinska; Fitness and eco-physiological response of a chytrid fungal parasite infecting planktonic cyanobacteria to thermal and host genotype variation. Parasitology 2018, 145, 1279-1286, 10.1017/s0031182018000215.

- Samarpita Basu; Katherine Mackey; Phytoplankton as Key Mediators of the Biological Carbon Pump: Their Responses to a Changing Climate. Sustainability 2018, 10, 869, 10.3390/su10030869.