Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Stephanie Daws | + 2141 word(s) | 2141 | 2022-01-27 12:21:12 | | | |

| 2 | Beatrix Zheng | + 180 word(s) | 2321 | 2022-02-10 01:57:10 | | | | |

| 3 | Beatrix Zheng | + 5 word(s) | 2326 | 2022-02-11 07:51:54 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Daws, S. Heroin Regulates Orbitofrontal Circular RNAs. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19286 (accessed on 15 January 2026).

Daws S. Heroin Regulates Orbitofrontal Circular RNAs. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19286. Accessed January 15, 2026.

Daws, Stephanie. "Heroin Regulates Orbitofrontal Circular RNAs" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19286 (accessed January 15, 2026).

Daws, S. (2022, February 09). Heroin Regulates Orbitofrontal Circular RNAs. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19286

Daws, Stephanie. "Heroin Regulates Orbitofrontal Circular RNAs." Encyclopedia. Web. 09 February, 2022.

Copy Citation

The number of drug overdose deaths involving opioids continues to rise in the United States. Many patients with opioid use disorder (OUD) that seek treatment still experience relapse. Perseverant opioid seeking behaviors represent a major challenge to treating OUD and additional therapeutic development will require insight into opioid-induced neurobiological adaptations.

opioids

self-administration

noncoding RNA

circular RNA

1. Introduction

Opioid overdose and deaths continue to rise in the United States, where nearly 190 people die every day from opioid intoxication [1]. Commonly used current pharmacological therapies to manage opioid dependence include buprenorphine and methadone, which both target the mu-opioid receptor [2][3]. However, chronic opioid use induces neurobiological adaptations which extend far beyond the opioid receptor [4]. Understanding the cellular and molecular pathways dysregulated by opioid exposure will provide insight into non-mu-opioid receptor targets that may be identified for more comprehensive treatment of OUD. To address this crucial issue, this study explored expression patterns of a novel class of RNA, circular RNAs (circRNAs), that are regulated in response to self-administration of the opioid heroin in a rat model of drug seeking. Although circRNAs have likely existed for a vast period of time [5], their presence and function in the nervous system have only recently been described [6][7][8][9][10]. In the context of opioid seeking, their role in drug-induced neuroadaptations is understudied and, for the majority of circRNAs, a complete mystery. Exploration of circRNAs in opioid exposure models provides a unique body of information that may inform substance abuse researchers of entirely unknown molecular signaling cascades associated with the critically complex and important phenotypes of opioid seeking.

CircRNAs are produced from pre-mRNA via non-canonical back-splicing events, during which the 3′ donor portion of an RNA exon attacks the 5′ region of an acceptor RNA exon [11]. This process is likely mediated by RNA-binding proteins (RBPs), such as Fus, Qki and Adar1, and results in a circular RNA product with covalently bound 3′-5′ ends that lacks both a 5′ cap and a poly-A tail [12][13][14]. The lack of a poly-A tail, as well as RNase resistance, increases the stability and longevity of circRNAs compared to mRNA [5]. While many circRNAs are purely exonal and noncoding [15], variation exists, with other circRNAs containing intronic portions [16]. Some exonic circRNAs even contain regions that are capable of protein-coding [17][18]. circRNAs are believed to have numerous cellular functions, ranging from regulation of linear parent mRNA transcription and protein translation to microRNA (miRNA) sponging and sequestration of RBPs [19]. Expression of circRNAs and linear transcripts from the same gene can differ. Sometimes the expression of circRNAs can exceed levels of their linear mRNA counterparts and the brain’s repertoire of circRNAs dramatically increases from birth to adulthood [15][20]. This suggests that circRNAs have a meaningful presence in the cell that can affect different biological processes in a sequence-specific manner and their expression correlates with an increase in cognitive ability [21]. Their effects may be long-lasting and such complexity may subserve neuropsychiatric conditions that are enduring over time. Simply put, circRNA capability is wide-ranging yet ambiguous.

Brain-enriched, synaptosomal circRNAs are present in the nervous system and many circRNAs are conserved from humans to rodents [6][21]. Therefore, circRNAs are poised to contribute to synaptic function in the brain and, in turn, behavioral output that results from synaptic transmission [6]. Three translational studies have reported aberrant circRNA expression in human neurological diseases and demonstrated in vivo rodent brain manipulation of circRNAs can rescue depression-like behavior in a model of chronic unpredictable stress as well as cognitive behavior and infarct volume in a cerebral focal ischemia model [7][9][22]. Thus, alteration of circRNA expression is sufficient to alter animal behavior and cognition. In the context of opioid exposure, a conserved circRNA from the mu-opioid receptor (Oprm1) is significantly increased after chronic morphine in mice and morphine alters the circRNA profile in the spinal cord, indicating that opioids induce a change in the circRNA profile [23]. Additionally, RNA-sequencing of circRNAs from the nucleus accumbens following conditioned place preference (CPP) described the contribution of a circTmeff-1-mediated pathway to the incubation of morphine CPP behavior [24].

2. Current Insights

circRNAs represent a novel species of RNA to study in models of addiction. Although circRNAs were discovered decades ago, limited exploration into the relationship between circRNAs and drug abuse has been completed thus far. While other studies in the neuroscience field have demonstrated that circRNAs can modulate neuronal function [7][22], the extent to which circRNAs contribute to the pathophysiology of substance use disorders is largely unknown. The work presented in the current study is the first to describe heroin-induced regulation of circRNAs in the brain.

In this entry, a set of heroin-associated circRNAs consistently regulated by heroin self-administration in the OFC of adult rats were identified. circGrin2b, circSlc24a2, circAdcy5, circAnks1 and circUbe2cbp were all identified with an unbiased microarray analysis of the circRNA profile altered by chronic heroin self-administration in male rats. The authors subsequently validated these results using qPCR in male and female rats to ensure reproducibility of the data. The authors did not detect any sex by treatment interactions when examining the expression of these putative heroin-associated circRNAs and do not conclude that regulation of the five validated circRNAs are sex-specific. Further analysis is required to examine sex-specific regulation of circRNAs after heroin exposure and accurate detection of some circRNA changes may require large sample sizes due to small effect sizes.

At the level of linear mRNA expression, The authors only detected significant upregulation of Grin2b in male animals and upregulation of Adcy5 in female animals. The upregulation of circGrin2b and circAdcy5 in these respective groups of animals may therefore be due to more copies of the linear isoforms of Grin2b and Adcy5 being produced in response to heroin. In contrast, upregulation of circAnks1a, circSlc24a2 and circUbe2cbp was not accompanied by a change in linear mRNA levels and may be due to heroin-induced modulation of a splicing factor. Drug-induced regulation of splicing factors has been previously reported [25][26].

Overall, this analysis suggested that the changes in circRNA expression detected in the heroin-exposed rats tends to be highly specific. Out of the five heroin-associated circRNAs that were validated, only one was dually regulated by sucrose self-administration, circUbe2cbp. The overlapping regulation of circUbe2cbp suggests that this circRNA may function as a more general response to any rewarding stimuli, including palatable food rewards. In contrast, the other four circRNAs—circGrin2b, circSlc24a2, circAdcy5 and circAnks1a—were not regulated by sucrose and appear to be specific for heroin reward. Whether any of these five circRNAs are also regulated in the OFC by other drug rewards, such as alcohol or cocaine, has not yet been determined as no such study has been performed, but circUbe2cbp seems the most likely candidate for regulation by multiple rewarding stimuli. The authors demonstrated that heroin self-administration of a 0.03 mg/kg dosage can induce regulation of 76 circRNAs in the OFC. This dosage of heroin has been used by many labs to model drug-seeking behavior and The authors have previously demonstrated that animals that have higher amounts of drug intake at this dosage typically have more drug-seeking behavior after extended forced abstinence [4][27]. However, this dosage does not result in incubation of heroin craving behavior, and The authors expect that a higher dosage protocol (e.g., 0.075 or 1.0 mg/kg/infusion) may result in an additional unique set of circRNAs specifically associated with long-lasting drug seeking behavior. Ideally, future studies will examine the contribution of circRNAs to a variety of drug paradigms, including withdrawal, incubation, reinstatement and extinction, using a variety of drugs (e.g., psychostimulants, nicotine, alcohol) to fully delineate the contribution of unique circRNA profiles to each drug behavior.

Interrogation of the putative microRNA pathways that may be affected by heroin-associated circRNAs revealed a list of microRNAs largely unstudied in the field of addiction neuroscience. The authors identified 26 microRNAs that are predicted to bind at least three heroin-associated circRNAs and an additional 12 microRNAs predicted to bind circGrin2b, circAdcy5, circAnks1a, circSlc24a2 or circUbe2cbp. Of these, let-7b-5p, which is predicted to bind circAdcy5, has been reported to be elevated in both the serum and the plasma of patients with heroin-use disorder [28][29]. Moreover, the putative targets of the heroin-associated circRNA-miRNA network include genes that have been studied extensively in the field of addiction, including Bax, Egr1, Elk1, Mapk3 (Erk1) and Ncam1. Specifically in the context of opioids, abstinence from heroin self-administration upregulates Egr1 in the frontal cortex of rats [30]. Levels of phosphor-Mapk3 (Erk1) were significantly downregulated in the prefrontal cortex of postmortem tissue from patients with opioid use disorder, although expression of Mapk3 (Erk1) has also been reported to be upregulated in the locus coeruleus and striatum of rats treated with morphine [31][32]. Regulation of Elk1 has been reported in the nucleus accumbens of rats that self-administered the same heroin dosage used here as well as in postmortem tissue from patients with heroin use disorder [4]. Thus, the function of circRNA–miRNA networks identified here may be to regulate mRNA pathways of genes that contribute to heroin-induced pathology. Further study into the complete circRNA–miRNA–mRNA pathways will illuminate a full picture of the complex interactions of these molecules in response to heroin exposure.

This study of circRNAs regulated by heroin in the OFC is the first unbiased analysis of heroin-induced circRNA expression published to date. Microarrays represent a suitable method of circRNA measurement but are not without limitations. The probes that are used in the microarray are only designed to detect the backsplice junction of a circRNA. Because of this, no information is available regarding the true size of the circRNA detected. Many circRNAs can arise from one linear RNA and various combinations of exons or introns may be included. The authors have listed the genomic size of the circRNAs detected in the microarray performed here as well as the predicted size of the validated heroin-associated circRNAs including only exons that exist between the genomic coordinates. An exception to this is circSlc24a2, which contains a backsplice junction that includes an intron. Previous studies have indicated that the majority of circRNAs only contain exons and our data describing the location of the backsplice junction in Figure 1 support this notion [15]. Limited options currently exist for profiling circRNAs, but future studies utilizing sequencing technology may have the ability to detect more circRNAs and include information about the actual size or exons/introns included in the sequenced circRNAs. Many sequencing companies require at least 5 ug of RNA, as opposed to the 2.5 μg required for a microarray, which is a limitation if a researcher desires to profile individual samples from animals without pooling samples. Until the input requirement for circRNA sequencing is reduced, it is unlikely that researchers utilizing mouse tissue would be able to generate enough high-quality RNA from brain areas critically involved in drug seeking such as the nucleus accumbens, central amygdala, basolateral amygdala, ventral tegmental area, prefrontal cortex or OFC. The authors were able to validate half of the candidate heroin-associated circRNAs identified in the microarray with subsequent biological replicate samples of OFC tissue. Typically, RNA sequencing data has been demonstrated to be more accurate than microarrays for mRNA and microRNA measurements; thus, moving forward with the adaptation of enhanced methodologies to perform circRNA sequencing would allow more researchers to perform the most accurate methods to profile circRNAs in a variety of experimental conditions.

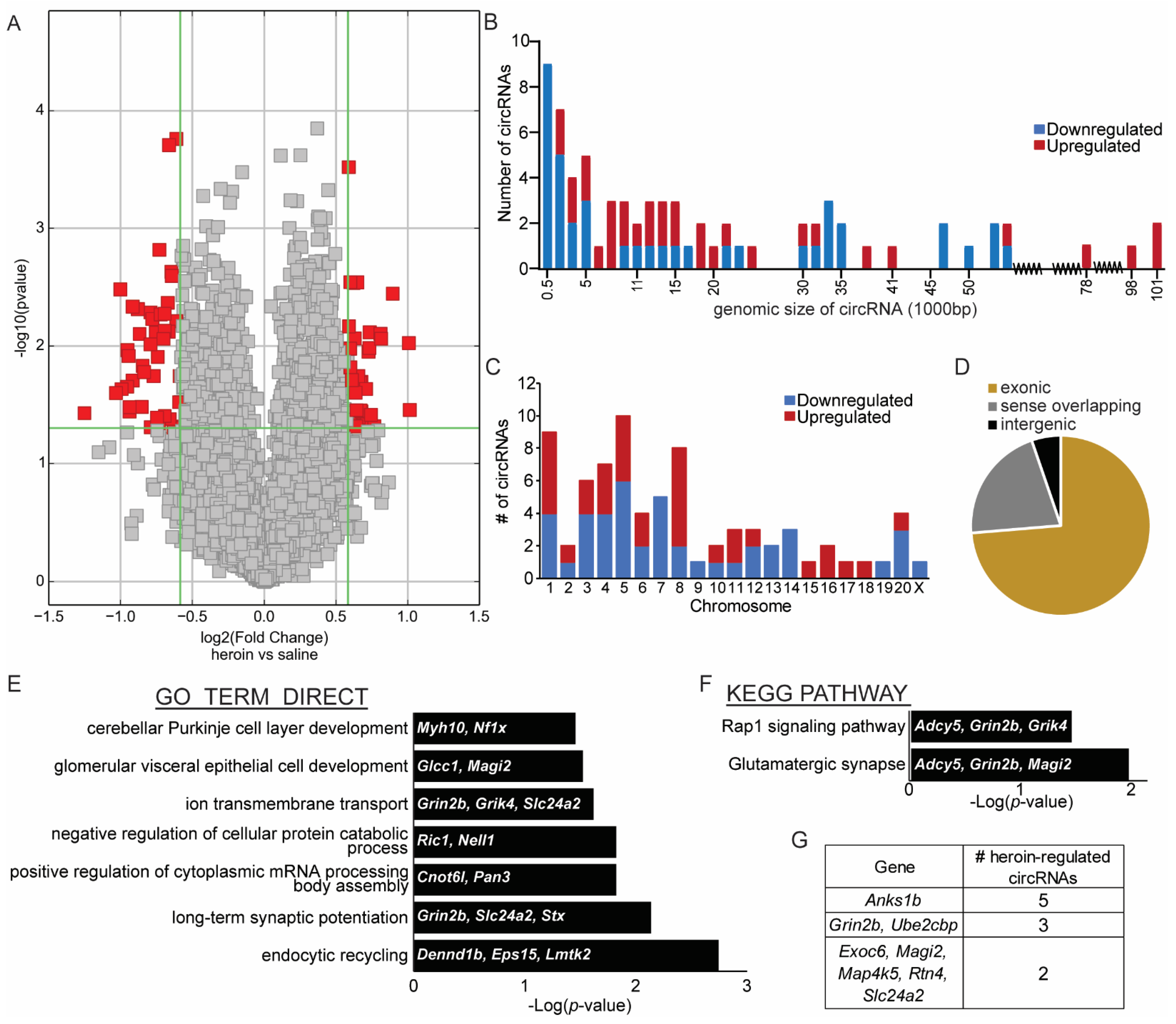

Figure 1. Heroin-associated circRNAs are derived from genes distributed across the genome and are mostly exonic. (A) Volcano plot depicting differentially expressed circRNAs in the OFC after heroin self-administration, as measured by microarray analyses. Red dots indicate circRNAs that meet statistical criteria for significantly different compared to saline. Grey dots represent circRNAs that are not statistically different between heroin and saline. (B) Genomic size in base pairs (bp) of each circRNA differentially expressed between heroin and saline animals, as indicated by the beginning and end position of the circRNA’s backsplice junction. (C). Chromosomal location of each differentially regulated circRNA. (D) Pie graph depicting the proportions of heroin-associated circRNAs that are exonic, intergenic, or sense overlapping. (E,F) Results from gene ontology analyses (E) and KEGG pathway analyses (F) indicating the terms significantly enriched from the gene list of linear mRNAs that give rise to differentially expressed heroin-associated circRNAs. For each term, the genes identified in the microarray analysis that belong to the term list are indicated. (G) List of repeat heroin-associated circRNAs that are derived from the same linear gene.

The existing literature on drug-induced circRNA expression has reported circRNA regulation in primary cortical neurons and the cerebellum in response to methamphetamine treatment, and in the striatum in response to cocaine self-administration [33][34][35]. None of the five heroin-associated circRNAs validated in the present study were regulated by psychostimulants in the aforementioned studies. This may be due to differences in treatment regimens and brain region. A study on postmortem nucleus accumbens tissue from patients with alcohol use disorder identified networks of predicted circRNA–microRNA–mRNA interactions that are regulated with chronic alcohol use [36]. Intrathecal injection of the opioid morphine regulated expression of circRNAs in the spinal cord [37] and systemic treatment with morphine regulated expression of circRNAs arising from the mu-opioid receptor in the whole brain of mice [23]. A morphine conditioned place preference (CPP) paradigm regulated the expression of a circRNA pathway arising from the gene Tmeff-1 in the nucleus accumbens [24]. circTmeff-1 and its predicted sponge targets, mir-541-5p and mir-6934-3p, contribute to maintenance of morphine CPP behavior [24], suggesting that circRNA pathways may be critical regulators of drug seeking. It is likely that each drug profile will induce a unique pattern of circRNA expression changes that vary from brain region to brain region, similar to the effects that have been observed with microRNA or mRNA profiling in drug-exposed animals and human patients. While these studies have paved the way for further exploration in the role of circRNAs in addiction, systematic dissection of the contribution of individual circRNAs to the pathophysiology of drug exposure or drug seeking behaviors is a monumental task that will hopefully begin in the decades to follow.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multiple Cause of Death Files, National Center for Health Statistics, 1999–2019; CDC WONDER Online Database. Available online: https://wonder.cdc.gov/ (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- Volpe, D.A.; McMahon Tobin, G.A.; Mellon, R.D.; Katki, A.G.; Parker, R.J.; Colatsky, T.; Kropp, T.J.; Verbois, S.L. Uniform assessment and ranking of opioid μ receptor binding constants for selected opioid drugs. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2011, 59, 385–390.

- Buresh, M.; Stern, R.; Rastegar, D. Treatment of opioid use disorder in primary care. BMJ 2021, 373, n784.

- Sillivan, S.E.; Whittard, J.D.; Jacobs, M.M.; Ren, Y.; Mazloom, A.R.; Caputi, F.F.; Horvath, M.; Keller, E.; Ma’Ayan, A.; Pan, Y.-X.; et al. ELK1 Transcription Factor Linked to Dysregulated Striatal Mu Opioid Receptor Signaling Network and OPRM1 Polymorphism in Human Heroin Abusers. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 74, 511–519.

- Jeck, W.R.; Sharpless, N.E. Detecting and characterizing circular RNAs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 453–461.

- You, X.; Vlatkovic, I.; Babic, A.; Will, T.J.; Epstein, I.; Tushev, G.; Akbalik, G.; Wang, M.; Glock, C.; Quedenau, C.; et al. Neural circular RNAs are derived from synaptic genes and regulated by development and plasticity. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 603–610.

- Wu, F.; Han, B.; Wu, S.; Yang, L.; Leng, S.; Li, M.; Liao, J.; Wang, G.; Ye, Q.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Circular RNA TLK1 Aggravates Neuronal Injury and Neurological Deficits after Ischemic Stroke via miR-335-3p/TIPARP. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 7369–7393.

- Gokool, A.; Anwar, F.; Voineagu, I. The Landscape of Circular RNA Expression in the Human Brain. Biol. Psychiatry 2020, 87, 294–304.

- Zhang, Y.; Du, L.; Bai, Y.; Han, B.; He, C.; Gong, L.; Huang, R.; Shen, L.; Chao, J.; Liu, P.; et al. CircDYM ameliorates depressive-like behavior by targeting miR-9 to regulate microglial activation via HSP90 ubiquitination. Mol. Psychiatry 2018, 25, 1175–1190.

- Piwecka, M.; Glažar, P.; Hernandez-Miranda, L.R.; Memczak, S.; Wolf, S.A.; Rybak-Wolf, A.; Filipchyk, A.; Klironomos, F.; Cerda Jara, C.A.; Fenske, P.; et al. Loss of a mammalian circular RNA locus causes miRNA deregulation and affects brain function. Science 2017, 357, eaam8526.

- Li, X.; Yang, L.; Chen, L.-L. The Biogenesis, Functions, and Challenges of Circular RNAs. Mol. Cell 2018, 71, 428–442.

- Conn, S.J.; Pillman, K.A.; Toubia, J.; Conn, V.M.; Salmanidis, M.; Phillips, C.A.; Roslan, S.; Schreiber, A.W.; Gregory, P.A.; Goodall, G.J. The RNA Binding Protein Quaking Regulates Formation of circRNAs. Cell 2015, 160, 1125–1134.

- Errichelli, L.; Dini Modigliani, S.; Laneve, P.; Colantoni, A.; Legnini, I.; Capauto, D.; Rosa, A.; De Santis, R.; Scarfò, R.; Peruzzi, G.; et al. FUS affects circular RNA expression in murine embryonic stem cell-derived motor neurons. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14741.

- Shi, L.; Yan, P.; Liang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Shen, J.; Zhou, S.; Lin, H.; Liang, X.; Cai, X. Circular RNA expression is suppressed by androgen receptor (AR)-regulated adenosine deaminase that acts on RNA (ADAR1) in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e3171.

- Jeck, W.R.; Sorrentino, J.A.; Wang, K.; Slevin, M.K.; Burd, C.E.; Liu, J.; Marzluff, W.F.; Sharpless, N.E. Circular RNAs are abundant, conserved, and associated with ALU repeats. RNA 2013, 19, 141–157.

- Rahimi, K.; Venø, M.T.; Dupont, D.M.; Kjems, J. Nanopore sequencing of brain-derived full-length circRNAs reveals circRNA-specific exon usage, intron retention and microexons. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4825.

- Zhao, H.; Zhou, Q.; Li, X. Protein Bait Hypothesis: circRNA-Encoded Proteins Competitively Inhibit Cognate Functional Isoforms. Trends Genet. 2021, 37, 616–624.

- Legnini, I.; Di Timoteo, G.; Rossi, F.; Morlando, M.; Briganti, F.; Sthandier, O.; Fatica, A.; Santini, T.; Andronache, A.; Wade, M.; et al. Circ-ZNF609 Is a Circular RNA that Can Be Translated and Functions in Myogenesis. Mol. Cell 2017, 66, 22–37.e9.

- Barrett, S.P.; Salzman, J. Circular RNAs: Analysis, expression and potential functions. Development 2016, 143, 1838–1847.

- Mahmoudi, E.; Cairns, M.J. Circular RNAs are temporospatially regulated throughout development and ageing in the rat. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2564.

- Rybak-Wolf, A.; Stottmeister, C.; Glažar, P.; Jens, M.; Pino, N.; Giusti, S.; Hanan, M.; Behm, M.; Bartok, O.; Ashwal-Fluss, R.; et al. Circular RNAs in the Mammalian Brain Are Highly Abundant, Conserved, and Dynamically Expressed. Mol. Cell 2015, 58, 870–885.

- Zimmerman, A.J.; Hafez, A.K.; Amoah, S.K.; Rodriguez, B.A.; Dell’Orco, M.; Lozano, E.; Hartley, B.J.; Alural, B.; Lalonde, J.; Chander, P.; et al. A psychiatric disease-related circular RNA controls synaptic gene expression and cognition. Mol. Psychiatry 2020, 25, 2712–2727.

- Irie, T.; Shum, R.; Deni, I.; Hunkele, A.; Le Rouzic, V.; Xu, J.; Wilson, R.; Fischer, G.W.; Pasternak, G.W.; Pan, Y.-X. Identification of Abundant and Evolutionarily Conserved Opioid Receptor Circular RNAs in the Nervous System Modulated by Morphine. Mol. Pharmacol. 2019, 96, 247–258.

- Yu, H.; Xie, B.; Zhang, J.; Luo, Y.; Galaj, E.; Zhang, X.; Shen, Q.; Liu, Y.; Cong, B.; Wen, D.; et al. The role of circTmeff-1 in incubation of context-induced morphine craving. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 170, 105722.

- Xu, S.-J.; Lombroso, S.I.; Fischer, D.K.; Carpenter, M.D.; Marchione, D.M.; Hamilton, P.J.; Lim, C.J.; Neve, R.L.; Garcia, B.A.; Wimmer, M.E.; et al. Chromatin-mediated alternative splicing regulates cocaine-reward behavior. Neuron 2021, 109, 2943–2966.e8.

- Bryant, C.D.; Yazdani, N. RNA-binding proteins, neural development and the addictions. Genes Brain Behav. 2016, 15, 169–186.

- Zanda, M.T.; Floris, G.; Sillivan, S.E. Drug-associated cues and drug dosage contribute to increased opioid seeking after abstinence. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14825.

- Gu, W.-J.; Zhang, C.; Zhong, Y.; Luo, J.; Zhang, C.-Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, C. Altered serum microRNA expression profile in subjects with heroin and methamphetamine use disorder. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 125, 109918.

- Liu, H.; Xu, W.; Feng, J.; Ma, H.; Zhang, J.; Xie, X.; Zhuang, D.; Shen, W.; Liu, H.; Zhou, W. Increased Expression of Plasma miRNA-320a and let-7b-5p in Heroin-Dependent Patients and Its Clinical Sig-nificance. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 679206.

- Kuntz, K.L.; Patel, K.M.; Grigson, P.; Freeman, W.; Vrana, K.E. Heroin self-administration: II. CNS gene expression following withdrawal and cue-induced drug-seeking behavior. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2008, 90, 349–356.

- Ortiz, J.; Harris, H.; Guitart, X.; Terwilliger, R.; Haycock, J.; Nestler, E. Extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases (ERKs) and ERK kinase (MEK) in brain: Regional distribution and regulation by chronic morphine. J. Neurosci. 1995, 15, 1285–1297.

- Ferrer-Alcón, M.; García-Fuster, M.J.; La Harpe, R.; García-Sevilla, J.A. Long-term regulation of signalling components of adenylyl cyclase and mitogen-activated protein kinase in the pre-frontal cortex of human opiate addicts. J. Neurochem. 2004, 90, 220–230.

- Li, J.; Shi, Q.; Wang, Q.; Tan, X.; Pang, K.; Liu, X.; Zhu, S.; Xi, K.; Zhang, J.; Gao, Q.; et al. Profiling circular RNA in methamphetamine-treated primary cortical neurons identified novel circRNAs related to methamphetamine addiction. Neurosci. Lett. 2019, 701, 146–153.

- Bu, Q.; Long, H.; Shao, X.; Gu, H.; Kong, J.; Luo, L.; Liu, B.; Guo, W.; Wang, H.; Tian, J.; et al. Cocaine induces differential circular RNA expression in striatum. Transl. Psychiatry 2019, 9, 199.

- Boroujeni, M.E.; Nasrollahi, A.; Boroujeni, P.B.; Fadaeifathabadi, F.; Farhadieh, M.; Nakhaei, H.; Sajedian, A.M.; Peirouvi, T.; Aliaghaei, A. Exposure to methamphetamine exacerbates motor activities and alters circular RNA profile of cere-bellum. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 144, 1–8.

- Vornholt, E.; Drake, J.; Mamdani, M.; McMichael, G.; Taylor, Z.N.; Bacanu, S.; Miles, M.F.; Vladimirov, V.I. Identifying a novel biological mechanism for alcohol addiction associated with circRNA networks acting as potential miRNA sponges. Addict. Biol. 2021, 26, e13071.

- Weng, Y.; Wu, J.; Li, L.; Shao, J.; Li, Z.; Deng, M.; Zou, W. Circular RNA expression profile in the spinal cord of morphine tolerated rats and screen of putative key circRNAs. Mol. Brain 2019, 12, 7.

More

Information

Subjects:

Biochemistry & Molecular Biology

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

654

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

11 Feb 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No