Central and peripheral nerve injuries can lead to permanent paralysis and organ dysfunction. In recent years, many cell and exosome implantation techniques have been developed in an attempt to restore function after nerve injury with promising but generally unsatisfactory clinical results. Clinical outcome may be enhanced by bio-scaffolds specifically fabricated to provide the appropriate three-dimensional (3D) conduit, growth-permissive substrate, and trophic factor support required for cell survival and regeneration. In rodents, these scaffolds have been shown to promote axonal regrowth and restore limb motor function following experimental spinal cord or sciatic nerve injury.

1. Introduction

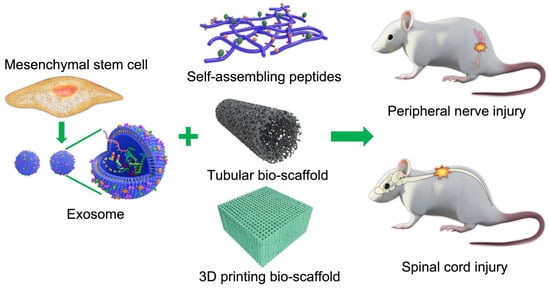

Scaffolds are well-known 3D porous functional biomaterials possessing constructive characteristics such as offering the proper position of cell location, cell adhesion, and deposition of the extracellular matrix (ECM) [1]. Moreover, scaffolds allow adequate gas transport, essential nutrients, and controlling factors to promote cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation. Based on their origin, scaffolds can be broadly classified/differentiated into natural/biological (such as collagen, chitosan, glycosaminoglycans, hyaluronic acid, demineralized, or native dentin matrix, etc.) and synthetic (such as bio-ceramics, calcium phosphate, and bioactive glasses, etc.) [1]. Biopolymer-based scaffolds are useful materials for 2D and 3D cell culture [2] and drug loading [3], and have demonstrated some value for tissue regeneration in various preclinical models [4][5]. Ideal scaffolds must possess the ability to replace damaged tissues with exogenous (transplanted) or endogenous cells of the correct tissue architecture for functional restoration [6]. For example, nerve damage is common following limb or head trauma and is frequently irreversible or difficult to treat [7]. One major reason for this irreversibility is the absence of a growth-permissive environment following injury, so biocompatible scaffold materials are needed to enhance repair [8][9]. In addition to high biocompatibility [10], scaffold materials should also have tunable mechanical strength [11], a large surface area, high porosity [12], and surface properties that mimic the physical and chemical properties of the ECM [13] and lack potential biotoxicity [14] in order to promote cell-adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation [15]. The appropriate chemical environment may be provided by biomaterials that can be loaded with cells or exosomes supplying nutritive and trophic factors to the injury site (illustrated in Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of cell/exosome and bio-scaffold combinations for the treatment of central and peripheral nerve injury.

2. Natural Polymeric Scaffolds

Natural polymeric bio-scaffolds are fabricated with structural components and chemical signaling molecules that stimulate cell survival, proliferation, differentiation, and tissue reconstruction, such as neurotrophic factors and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). The correct combination of factors and appropriate bioavailability is required for nerve regeneration after injury. Natural polymers used as structural components include various polysaccharides such as alginate, hyaluronic acid, chitin, and chitosan, and polymeric proteins such as gelatin, collagen, silk fibroin, fibrin, and keratin

[16][17]. All of the polymers have excellent biocompatibility and bioactive properties and so may allow for better scaffold–tissue interactions as well as cell adhesion, proliferation, and eventual tissue restoration

[18]. However, some lack the biophysical characteristics for functional recovery.

2.1. Polysaccharide-Based Biomaterials

2.1.1. Hyaluronic Acid

Hyaluronic acid (HA) is a glycosaminoglycan component of ECM that facilitates the interactions of cells with other extracellular molecules to promote various physiological processes

[19].

HA has been used successfully with different substrates to support neurite out-growth, differentiation, and proliferation. Further, HA hydrogel has been used to promote the survival and proliferation of neural precursors for PNS repair

[20] and has shown promise for CNS repair. It has mechanical properties suitable for supporting neural progenitor cell differentiation as potential neurodegenerative disease treatments

[21]. Long-chain HA is essential for supporting ECM components of different molecular weights in vivo

[22]. An HA scaffold containing ciliary neurotrophic factor stimulated endogenous neurogenesis and facilitated neural-network formation, synaptogenesis, and motor recovery following T8 spinal cord transection in rodents

[23].

2.1.2. Alginate

Alginate, an extract of brown seaweed, is used for a variety of biomedical applications. Its chemical composition of guluronic and mannuronic acid confers greater chemical flexibility compared to other biocompatible degradable materials and may more closely mimic the physical properties of mammalian ECM

[24]. Physical and mechanical properties are also easily adjustable using various chemical reactions

[25] and physical crosslinking using Ca

2+ with negligible immunogenicity

[26]. While alginate can promote nerve regeneration under certain conditions, mechanical strength is insufficient to allow physical loading, and degradation is relatively rapid, necessitating the addition of other polymers

[27][28][29].

2.1.3. Chitosan and Chitin

Chitin is the most abundant linear polysaccharide homo-polymer of the glycosaminoglycan N-acetyl-D-glucosamine in crustacean shells. Chitosan-silk hydrogel as a carrier for gingival MSC-derived exosomes was reported to accelerate neurogenesis, angiogenesis, re-epithelization, and collagen formation

[30]. In a mouse hind-limb repair model as well, animals receiving MSC exosomes encapsulated with chitosan exhibited better angiogenesis and tissue regeneration than controls

[31].

Chitosan is also commonly used to support axon regrowth

[32] and reduce scar tissue formation

[33] for peripheral nerve regeneration. Further, both reabsorbing chitosan and its degradation products (chito-oligosaccharides) have been shown to promote nerve regeneration

[34]. Using appropriate fabrication techniques, chitosan nerve guidance conduits can be produced for cell-based therapies

[35][36].

3. Protein-Based Biomaterials for Nerve Injuries

3.1. Collagen

Collagen scaffolds have numerous advantages for tissue engineering

[37]. Collagen is a good medium for cell and drug delivery

[38] and is sufficiently flexible for nerve conduits with physical features tailored for different sections of the nerve pathway

[39]. In addition, it can support topographical cues that allow axonal regrowth and facilitate cell-adhesion, survival, and migration along different nerve tract domains

[40]. Such collagen nerve conduits have been demonstrated to support nerve regeneration and re-innervation of muscle

[41]. In a clinical study, a conduit made by mixing type I and III collagen filled with collagen filaments was effective as an autologous implant for treating nerve injury, with 75% of patients reporting sensory recovery after 12 months

[42]. A collagen scaffold embedded with neural stem cells was also reported to promote nerve regeneration and motor function in a T8 SCI rat model

[43].

3.2. Laminin

Laminins are high molecular weight proteins that constitute the major component of the ECM basal lamina layer, a protein network that acts as a structural foundation for most organs and cells. Laminin proteins are also a major component of the brain ECM and function as cell adhesion molecules influencing cell survival, differentiation, and plasticity. For instance, laminins were shown to promote the survival and differentiation of transplanted dopaminergic neuron precursors by suppressing cell death-associated protein

[44]. Additionally, laminin present in the vascular basal lamina can act as a conduit for the growth of axons

[45] as it is expressed endogenously in the basal membrane surrounding peripheral nerves, capillaries, and skeletal muscle. Further, it can regulate the proliferation, differentiation, and myelin production of Schwann cells. Laminins are also secreted by Schwann cells at lesion sites

[46], strongly suggesting functions in nerve repair. For these reasons, laminins are considered promising scaffold components for nerve repair

[47][48]. Indeed, nerve guides filled with laminin yielded enhanced axonal regeneration

[49], likely by increasing the interactions with integrin receptors.

3.3. Gelatin

Gelatin-based hydrogels may have low viscosity at physiological temperature, limiting the maintenance of the 3D structure. To increase its strength, gelatin is combined with other polymers, such as collagen, fibrin, or various synthetic and photo-crosslinkable polymers

[50][51]. Though different kinds of gelatin-based hydrogels such as micro- and nano-sized particles, nanofibrous scaffolds, enzyme-mediated, and in situ-generated gelatin hydrogels were reported

[52]; the enzymatically prepared gelatin hydrogels have been widely used in nerve regeneration. For instance, the enzymatically prepared gelatin hydrogels combined with human umbilical cord MSCs have been effectively applied for nerve injury treatment

[53][54].

3.4. Silk Fibroin

Silk fibroin (SF) is a natural biopolymer with high biocompatibility

[55] and low immunogenicity

[56] as well as sufficient biodegradability

[57], physical strength, and flexibility for in vivo applications

[58]. SF has been shown to promote cell attachment and survival for tissue repair and restoration

[59]. Further, SF can promote proliferation of Schwann cells

[60] and so may be especially effective for peripheral nerve regeneration. In addition, an SF-based hydrogel was also demonstrated to support neuronal growth for central nerve tissue repair

[61]. Critically, the orientation of SF fibers can guide the direction of neuronal growth

[62]. These unique properties may explain the efficacy of SF fibers for promoting neural cell proliferation following auto- or allo-grafting

[63]. In addition, SF can deliver bioactive compounds to the injury site and reduce both tissue inflammation and oxidative stress. Moreover, SF fibers show slow biodegradation

[64]. In a traumatic brain injury model, SF reduced brain damage and promoted neurological function

[65].

SF scaffolds can be synthesized in various conformations such as fibers, mats, films, and hydrogels. This adaptability may permit its application for the treatment of several neurogenerative diseases in addition to traumatic nerve injury. Due to its unique physico-chemical and biological properties, SF is a promising material for tissue engineering. Recently, SF 3D-scaffolds enriched in MSC-derived exosomes were also reported to enhance bone regeneration in rats

[66].

3.5. Fibrin

Fibrin is a fibrillary protein formed during blood clotting. It is mainly involved in hemostasis, but also contributes to wound healing by forming a temporary matrix surrounding the lesion

[67]. Changes in the fibrinogen-to-thrombin ratio can modulate the mechanical properties of fibrin hydrogels for effective treatment of human spinal cord injury

[68]. Due to its high biocompatibility, fibrin has been used as a vehicle and injectable biomaterial for transplantation of cells to facilitate neural regeneration

[69]. The mechanical properties of fibrin hydrogels are also highly tunable by altering the fibrin concentration and preparation temperature

[70].

3.6. Keratin

Keratin can be extracted from human hair and further processed to obtain a keratin sponge structure. Compared to many synthetic polymers, keratin appears to possess the surface hydrophilicity, biodegradability, biocompatibility, and bioactivity of an effective scaffold material. However, keratin-based biomaterials have low mechanical strength and degrade rapidly, and so are usually modified using various crosslinking agents for scaffold construction

[71], while keratin alone is used primarily as a conduit filler. Keratin/alginate scaffolds have been applied successfully for tissue regeneration in vitro

[72]. Furthermore, keratin has been shown to promote Schwann cell proliferation in vitro and improve nerve regeneration in vivo

[73][74].

4. Self-Assembling Peptides

Self-assembling peptides (SAPs) can spontaneously form well-organized nanostructures, a property highly advantageous for a wide range of biomedical applications. For nerve injuries, SAPs have been used as biocompatible carriers to provide the appropriate 3D structure for embedded nerve cells and the release of growth factors and drugs

[75]. Moreover, SAPs have been shown to provide a microenvironment conducive to cell proliferation and differentiation as well as neural-network reconstruction and functional restoration of injured nerves

[76][77][78].

SAPs may be ideal building blocks for scaffolds and can also be used as soft fillers to surround harder synthetic biocompatible biopolymers. In general, the scaffold must imitate the natural biomechanical properties of the regenerating tissue and permit the cell–substrate and cell–cell interactions necessary for regrowth. Further, bio-absorption must be appropriately matched to tissue regeneration kinetics and result in little inflammation

[79].

5. Three-Dimensional Printed Scaffolds

Three-dimensional (3D) bio-printing is used extensively in regenerative medicine, cancer research, and the pharmaceutical industry to fabricate structures combining cells, growth factors, and cell substrates. Three-dimensional printed scaffolds have been demonstrated to stimulate cell attachment, growth, and organization resembling nervous tissue. In addition, 3D bio-printing has been used to create scaffolds with defined porosity and inter-pore channel structure. Currently, two modes of 3D printing are used to create 3D cell-embedded scaffolds and scaffolds with supportive bio-ink. Both types can help to reconstruct the cellular structure of the original tissue. Bio-ink printing can quickly form porous 3D scaffolds encapsulating human neural stem cells able to differentiate and replace lost function and/or support the growth of other neurons and glia

[80]. For example, Bociaga et al. demonstrated that bio-printing can produce scaffolds with excellent microstructural features for cell growth

[81]. Moreover, these fabrication techniques have shown promise for printing tissue components such as grafts and organs. One recent study reported the development of a microsphere-loaded bio-ink to print scaffolds with neural progenitor cells (NPCs) for neural tissue repair

[82], and another reported promising results using printed scaffolds for regeneration following sciatic nerve injury

[83]. Some of these 3D bio-printed biomaterials are illustrated in

Figure 6. In addition, recent examples of bio-scaffold applications for in vitro and in vivo nerve injury repair are summarized in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

Table 1. Recent in vitro studies using bio-scaffolds for nerve injury repair.

| Bio-Scaffold |

Cell Type |

Disease |

Results |

Reference |

| PDGF-MS-containing tubular scaffold |

Neural progenitor |

Spinal cord injury |

Promoted both growth and migration of MUSE-NPCs |

[84] |

| 3D collagen scaffold |

Glioma |

Glioma |

Good biocompatibility with glioma cells and able to influence gene expression and biological functions |

[85] |

| Scaffold incorporating salmon fibrin, HA, and laminin |

Human neural stem cells |

Neurovascular niche |

Enhanced vasculogenesis from human endothelial colony-forming cell-derived endothelial cells for cellular therapeutics |

[86] |

| Chitosan-based scaffold |

Radial glia |

Traumatic brain injury |

Effective cellular and growth factor delivery vehicle for cell transplantation |

[87] |

| Collagen scaffold |

Neural stem cells |

Spinal cord injury |

Promoted nerve regeneration and locomotor function |

[43] |

Abbreviations: PDGF-MS: platelet-derived growth factor-microsphere; MUSE-NPCs: neural progenitor cells differentiated in vitro from multilineage-differentiating stress-enduring cells.

Table 2. Recent studies using bio-scaffolds for nerve injury repair in animal models.

| Bio-Scaffold |

Species |

Disease |

Results |

Reference |

| Poly (propylene fumarate) polymer with collagen biomaterial |

Rat |

Spinal cord injury |

Promoted neurotrophy, neuroprotection, myelination, and synapse formation, and reduced CSPG deposits and fibrotic scarring |

[88] |

| 3D collagen-based scaffold |

Mouse |

Neuroblastoma |

Promoted microenvironment within scaffold and helps in cell transplantation and drug delivery |

[89] |

| Collagen nerve conduit |

Rat |

Sciatic defect |

Promoted motor nerve regeneration |

[41] |

| Chitosan hydrogel scaffold |

Mouse |

Ischemic brain injury |

Improved tissue regeneration following hind-limb ischemia |

[31] |

| 3D fibrin hydrogel scaffold |

Rat |

Spinal cord injury |

Promoted aligned axonal regrowth and locomotor function |

[90] |

| Collagen/heparin/VEGF scaffold |

Rat |

Traumatic brain injury |

Provided an excellent microenvironment for nerve regeneration |

[91] |

| Collagen scaffold |

Rat |

Spinal cord injury |

Improved locomotor function and nerve regeneration |

[43] |

| Silk fibroin scaffold |

Rat |

Traumatic brain injury |

Neuroprotection |

[65] |

RADA16-BDNF

self-assembling peptide hydrogel scaffold |

Rat |

Traumatic brain injury |

Enhanced the growth, survival, and differentiation of MSCs by providing a favorable microenvironment |

[92] |

| Chitin scaffold |

Rat |

Sciatic nerve injury |

Improved sciatic nerve regeneration, myelin sheath formation, and functional recovery |

[93] |

| Keratin sponge |

Rat |

Sciatic nerve injury |

Regulated inflammatory cytokine release from macrophages, axon extension, and nerve regeneration |

[73] |

| Fibrin hydrogel |

Rat |

Sciatic nerve defect |

Promoted regeneration as well as the secretion and signaling of multiple neurotrophic factors |

[94] |

| Keratin sponge |

Rat |

Spinal cord injury |

Improved functional recovery and inhibition of inflammatory response through macrophage polarization |

[74] |

Abbreviations: CSPG: chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor; MSCs: mesenchymal stem cells.

6. Bio-Scaffolds for Exosomes

Many studies were performed to assemble ionic cross-linking bio-scaffolds for exosome maintenance and release. In this regard, alginate hydrogel is considered one of the best bio-scaffold for encapsulating exosomes. For instance, an exosome-loaded alginate scaffold has been reported to improve collagen production, skin regeneration, and angiogenesis in the wound area

[95]. In our previous study, an alginate scaffold loaded with MSC exosomes was also developed to treat nerve injury-induced pain

[96].

In a sciatic nerve defect model, a chitin conduit embedded with human gingiva MSC-derived exosomes were found to promote Schwann cell proliferation and axon growth from the dorsal root ganglion

[97]. In addition, this scaffold increased the number and diameter of nerve fibers and enhanced myelin formation, nerve transmission, and motor function. In another SCI model, exosomes embedded within peptide-modified hydrogel stimulated nerve regeneration and preserved urinary function

[98]. Recent studies on exosome scaffolds for nerve injury repair are summarized in

Table 3.

Table 3. Recent examples of exosome scaffold use in nerve injury models.

| Bio-Scaffold |

Exosome Source |

Disease |

Results |

Reference |

| Peptide-modified adhesive hydrogel |

Human MSC-derived |

Spinal cord injury |

Promoted nerve regeneration and protected urinary tissue by easing oxidative stress and inflammation |

[98] |

| Alginate scaffold |

Human umbilical cord MSC-derived |

Nerve injury-induced pain |

Anti-nociceptive, anti-inflammatory, and neurotrophic effects |

[96] |

| Chitin conduit |

Human gingiva MSC-derived |

Rat sciatic nerve defect |

Increased the number and diameter of nerve fibers and promoted myelin formation |

[97] |

| Chitosan hydrogel |

Human placental MSC-derived |

Hind-limb ischemia |

Enhanced angiogenesis and tissue regeneration |

[31] |

| Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide 38 |

Retinal ganglion cell (RGC)-derived |

Traumatic optic neuropathy |

Promoted retinal ganglion cell survival and axon regeneration |

[99] |