Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Martina Mascaro | + 2379 word(s) | 2379 | 2022-01-19 03:10:40 | | | |

| 2 | Jason Zhu | Meta information modification | 2379 | 2022-02-08 02:53:47 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Mascaro, M. Microtubular TRIM36 E3 Ubiquitin Ligase. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19166 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Mascaro M. Microtubular TRIM36 E3 Ubiquitin Ligase. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19166. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Mascaro, Martina. "Microtubular TRIM36 E3 Ubiquitin Ligase" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19166 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Mascaro, M. (2022, February 07). Microtubular TRIM36 E3 Ubiquitin Ligase. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19166

Mascaro, Martina. "Microtubular TRIM36 E3 Ubiquitin Ligase." Encyclopedia. Web. 07 February, 2022.

Copy Citation

TRIM36 is a microtubule-associated E3 ubiquitin ligase that plays a role in cytoskeletal organization, and according to data gathered in different species, coordinates growth speed and stability, acting on the microtubules’ plus end, and impacting on cell cycle progression.

tripartite motif (TRIM) E3 ubiquitin ligases

TRIM36

microtubules

Embryonic development

Spermatogenesis

1. Introduction

The tripartite motif (TRIM) family represents the largest sub-family of RING domain-containing proteins. In addition to an N-terminal RING domain, these proteins share the presence of one or two additional Zn-binding B-box domains (B-box 1 and B-box 2) and a coiled-coil region, hence the term tripartite motif (TRIM) [1]. The RING domain confers E3 ubiquitin ligase activity within the ubiquitination cascade to the TRIM family members [2][3]. Additionally, E3 ligase-independent biological roles of TRIM proteins have been proposed, e.g., RNA-binding [4]. As ubiquitination regulates the stability and activity of many proteins, if not all, it is no surprise that this family is implicated in a variety of cellular processes, from transcription to apoptosis, from cell cycle regulation to signal transduction [5][6][7]. This involvement, often associated with spatial and temporal specific expression, implicates TRIM proteins in many physiological processes and pathological conditions. These pathologies are multiple and, frequently, each TRIM family member can have pleiotropic functions.

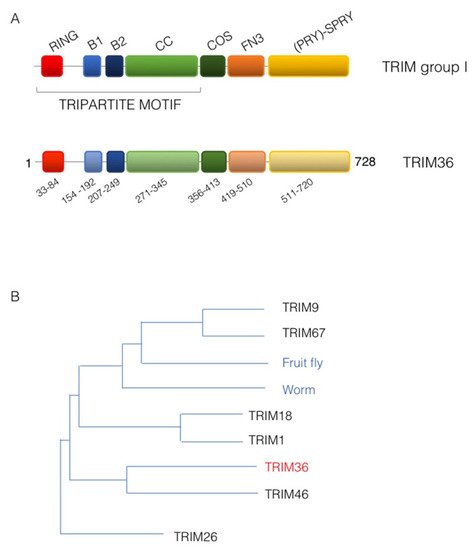

According to the domain(s) displayed C-terminal to the tripartite motif, an extra sub-classification of the TRIM family, counting more than 70 members in humans into at least nine groups, was proposed [8]. Subclass I TRIM family members are characterized by the presence in the tripartite motif of both B-box 1 and B-box 2. Subclass I feature is a composite C-terminal portion that includes: a COS (C-terminal subgroup one signature) domain, employed by these proteins to associate with the microtubules, followed by a fibronectin type III repeat (FN3) and a PRY-SPRY domain [8] (Figure 1A). The members of this subgroup are indeed all associated with the microtubular apparatus and are mainly expressed during embryonic development where they are often involved in the definition of several developing structures [8][9][10][11]. Accordingly, mutations in some of these genes are associated with paediatric pathologies caused by developmental malformations [11].

Figure 1. TRIM36 domain structure. (A) Schematic representation of the domain structure of TRIM sub-group I family members (upper scheme) and human TRIM36 with the same color code and the indication of the residue limits predicted for each domain as per UniProt Q9NQ86 (lower scheme). RING, RING domain; B1, B-box 1 domain; B2, B-box 2 domain; CC, Coiled-coil region; COS, C-terminal subgroup one signature; FN3, Fibronectin type 3 repeat; SPRY, based on a sequence repeat discovered in the splA kinase and ryanodine receptors. (B) Phylogenetic tree showing the evolutionary relationship of TRIM sub-group I family members. The human TRIM family members are shown together with the only member of this sub-group present in invertebrates, represented here by the fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster, Dmel, CG31721) and the worm (Caenorhabditis elegans, madd-2).

2. Tripartite Motif 36 (TRIM36)

In mammals, TRIM subgroup I is composed of six evolutionarily close members that present orthologous genes in vertebrate species but that are represented only by a single ancestral homologue in invertebrate (Figure 1B) [8][12]. The TRIM36 protein shares the classic TRIM subgroup I domain composition and is 728 amino acids long in humans (UniProt Q9NQ86) (Figure 1A). It was first identified in 2003 in mouse and named Haprin (from the haploid germ cell-specific RBCC protein) in a haploid germ cell specific cDNA library of mouse testis [13]. The human ortholog, RBCC728/TRIM36, of the Haprin gene was then identified and mapped on chromosome 5q22.3 [14].

As for its initial identification, in adult mice, the Trim36 transcript was confirmed to be abundantly expressed in testis with barely undetectable expression in other organs. Upon testis fractionation the transcript was detected in the germ cell fraction and was not present in somatic cells, e.g., Sertoli and Leydig cells. Furthermore, the transcript was not found in testis until the fourth postnatal week, when elongated spermatids appeared, to then increase with age [13]. A corresponding trend was observed for its protein product [13]. Expression in testis was confirmed in humans where three transcript isoforms sharing the same expression pattern were reported. Two of these are predicted to produce full TRIM36 proteins displaying few amino acid differences at the very N-terminus before the RING domain, whereas the third isoform is predicted to produce non-functional peptides, if any [15] (UniProt Q9NQ86). During mouse development, Trim36 was detected by RNA in situ hybridization in the neural tube and developing brain in E14.5 embryos [16].

3. TRIM36 Associates with the Microtubules

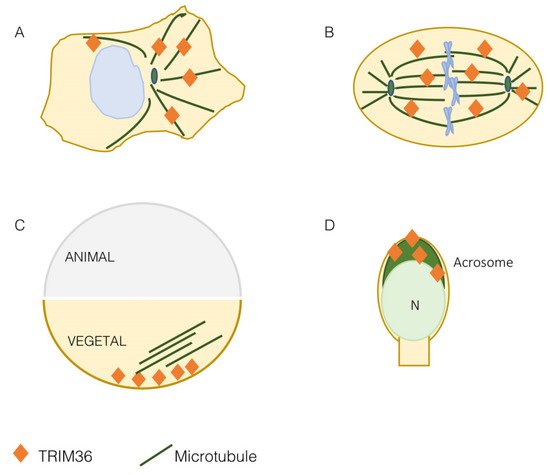

At first, TRIM36 was found to decorate filaments in the cytoplasm of transfected COS-7 cells and the same was observed for the endogenous protein in the 22RV1 and LNCaP cell lines [14]. This subcellular localization was then confirmed and assessed as microtubular during the identification and characterization of the TRIM group I specific microtubule-interacting domain, the COS (C-terminal subgroup one signature) box in COS-1 cells [8]. This result was confirmed in other cell lines where the presence of TRIM36 was also observed on mitotic spindle and cytokinetic midbody microtubules [16][17] (Figure 2A,B). Microtubules are essential protein polymers that serve as structural elements in eukaryotic cells and whose dynamics is tightly controlled for proper cytoskeletal organization [18].

Figure 2. TRIM36 is a microtubule-associated protein. TRIM36 is associated with the microtubular apparatus in mammalian cells both at interphase (A) and on the mitotic spindle (B). In the Xenopus laevis egg, both before and after fertilization, TRIM36 is present in the vegetal pole to organize the microtubule array needed to guide dorsal determinants during cortical rotation (C). In elongated spermatids and spermatozoa, TRIM36 is detected in the acrosome (dark green); N, nucleus (D).

Silencing TRIM36 in HeLa and LN229 cell lines leads to disrupted microtubules and disorganized mitotic spindles [16]. The effect on the spindle can correlate with the observed reduced cell proliferation and increased apoptosis and with the opposite observation when exogenous TRIM36 was expressed [16]. However, this aspect should be further investigated as another report found a markedly decreased cell growth rate following TRIM36 overexpression in NIH3T3 [17]. Moreover, a role in mitosis is supported by the interaction of TRIM36 with CENP-H, which is one of the kinetochore proteins that plays an important role in chromosome segregation [17]. Although the functional role of TRIM36-CENP-H interaction is still unknown, it is interesting that alterations in CENP-H protein levels are associated with the disappearance of the centromere from mitotic chromosomes and, as a consequence, to missing chromosomes during segregation and cell cycle delay [19].

More data on the role of TRIM36 on the microtubular apparatus were gathered when this TRIM was found to be implicated in the organization of the Xenopus egg vegetal microtubular array [20] (Figure 2C). As detailed in the next section, in eggs depleted of maternal trim36, no vegetal microtubule assembly and cortical rotation are observed. Indeed, trim36-depleted eggs either lacked microtubule organization completely or exhibited fragmented microtubules in a loose organization [20]. Depletion of trim36 was not affecting microtubule growth and polymerization during the initial phases of cortical rotation, but subsequent cortical displacement did not initiate in trim36-depleted embryos and this effect was accompanied by the lack of formation of robust parallel arrays [21]. The precise organization of microtubules makes them polar structures displaying a directionality throughout their length with two different ends. Polarity underlies differences in the kinetics of subunit addition and loss at the two microtubule ends. The faster-growing end is called the ‘plus end’ and the slower growing end is referred to as the ‘minus end’ [18]. Plus ends’ detection in Xenopus eggs confirmed that, upon trim36-depletion, their number was reduced and their behavior chaotic. In addition, tracking of microtubule plus ends growth was non-directional in trim36-depleted eggs, which correlates with lack of cortical rotation. This led to conclude that trim36 might act to coordinate plus end growth thus differentially modulating growth speed and stability of local vegetal arrays necessary for cortical rotation [21].

4. TRIM36 Function in Embryonic Development

Most of the data available on the role of TRIM36 during development are obtained from the Xenopus model where the frog ortholog was found implicated in the definition of the very early developmental stages. The Xenopus trim36 maternal transcript was found to be enriched at the vegetal cortex of oocytes where it was kept anchored by the RNA-binding protein dead-end 1 [20][22]. The vegetal pole localization was also maintained after egg fertilization and up to 4- to 8-cell-stage embryos. Then, during early neurulation, trim36 mRNA was detected outside the germ plasm in the developing neural tube, enriched at the midbrain-hindbrain boundary [20].

Xenopus embryos derived from fertilization of oocytes injected with antisense oligos against trim36 develop normally until gastrulation but show delay in blastopore lip formation [20]. At the completion of gastrulation, the majority of them failed to form neural plates. By the early tailbud stages, trim36-depleted embryos were either radially ventralized, in the extreme cases, or formed partial axes lacking anterior structures in the less severe cases. Trim36-depleted embryos were shown to lack well-formed neural tubes, somites and notochords, in some cases forming unorganized lumps of somite tissue in the midline occupying the notochord left space. This defective dorsal tissue formation is possibly exerted along with β-catenin likely by acting upstream or in parallel to Wnt/β-catenin activation [20]. As reported in the previous section, trim36 is implicated in maintaining proper organization of the egg vegetal microtubular array that is necessary for cortical rotation to occur. In amphibian fertilized eggs, indeed, axial determination requires a dorsally directed rotational movement of the egg cortex, cortical rotation, at the first cell cycle, and which is driven by a parallel array of microtubules beneath the cortex, transporting dorsalizing factors to the dorsal side of the gastrula [23]. Cortical rotation mediated by trim36-organized microtubule array is thus required to specify the dorso–ventral axis and induce dorsal structures and this action necessitates integral E3 ubiquitin ligase activity, although the molecular targets are still unknown [20].

A Trim36 knock-out mouse line was generated and, unexpectedly, adult homozygous null mice were undistinguishable from heterozygous and wild-type mice. Further, no abnormal development and breeding of Trim36 null mice were observed suggesting the presence of redundant genes in rodents [24]. However, when it comes to humans, TRIM36 is another member of the TRIM subgroup I implicated in a birth defect. A homozygous Pro508Thr missense mutation within the TRIM36 SPRY domain was detected in a 20-week-old fetus conceived of Indian consanguineous parents [16]. This fetus was affected by anencephaly (APH, OMIM 206500), an extreme form of neural tube defect that is quite common in India with 2.1:1000 births reported [25]. Anencephaly is characterized by the absence of cranial vault and brain tissues in the fetus and is incompatible with life. Early in embryogenesis, lack of closure of the cranium neuropore leads to neural tube defects leading to exencephaly at first and consequent degeneration of brain tissues in later stages [26]. The mutation, detected in the first place by whole-exome sequencing, segregates with the disorder in the family [16]. To date, this remains the only TRIM36 pathogenic variant so far reported in APH cases. Proline 508 is conserved in 26 species and the mutant protein is unstable if compared to the wild-type protein in HeLa cells and it is consistently less abundant in the APH fetus [16]. As observed for TRIM36 silencing, exogenous expression of the APH-associated mutation Pro508Thr leads to disorganized microtubules and apoptosis further supporting a pathogenetic role of this mutant [16]. Of note, TRIM36 is needed in both frog and human to determine the correct specification and closure during neurulation.

5. 5-TRIM36 role in Spermatogenesis

Spermatogenesis consists of three major events: the proliferation and differentiation of spermatogonia, the meiotic events of spermatocytes at prophase and morphological changes during differentiation from the haploid round spermatids to mature sperm. During haploid germ cell differentiation, referred to as spermiogenesis, molecules related to chromatin condensation, flagellum development and acrosome biogenesis are specifically expressed [15][27]. As mentioned above, Trim36 is expressed in haploid germ cells of mice testis, in particular, the protein is detected in elongated spermatids, at the late steps of germ cell development, and its presence is restricted to the acrosomal region (Figure 2D) [13]. The acrosome is a large Golgi-derived vesicle located in the anterior head of the sperm, which develops during spermiogenesis and contains enzymes needed for the digestion of the zona pellucida of the egg[15][27]. Trim36 is not simply detected in the acrosome, but also participates in the acrosome reaction[13]. Beside the indication of Trim36 function during the acrosome reaction, this also suggests the need of Trim36 E3 ligase activity to exert this role. After the acrosome reaction, Trim36 is likely released as it is observed only in the acrosome of intact cells but not in the acrosome reacted cells [13]. Although the function of Trim36 in acrosome reaction is still unknown, it was speculated that SNARE-related components, e.g., Rab3a, SNAREs and actin, might interact with it [13][15]. Moreover, whether Trim36 present in the crescent-shaped acrosome is somewhat associated with microtubules is still unknown.Furthermore, Trim36 null mouse-derived spermatozoa showed lower total and progressive motility and less complex motility patterns[24]. However, time-series analysis of the occurrence of the acrosome reaction in Trim36-deficient spermatozoa showed no significant difference with respect to that of spermatozoa from wild-type mice[24]. As for other parameters, macroscopic and histological observation of testes and seminal vesicles of the Trim36-null mice did not show any significant differences in morphogenesis and spermatogenesis function. These mice had a normal number of epididymis-recovered spermatozoa and, most importantly, all males were fertile and produced normal litters. However, when fertilization was carried on in vitro, Trim36-deficient spermatozoa were incapable of fertilizing oocytes [24]. The reason why Trim36-deficient sperms can fertilize in vivo but not in vitro is unknown. It is likely that in vivo additional factors, potentially components within the female tract, may compensate for the absence of active Trim36.

TRIM36 is expressed in the acrosomal region of different species and it has been reported to participate in the acrosome reaction and in spermatogenesis development, at least in vitro. However, the exact function in vivo and the molecular mechanisms involved still remain important open questions to address to fully understand TRIM36 physiological and pathological role in spermatogenesis.

Finally, TRIM36 E3 ubiquitin ligase activity has been demonstrated in vitro but no natural substrates have been identified to date. Researchers believe this is a crucial gap to fill to better understand the physiological and pathological pathways regulated by TRIM36 during development and spermatogenesisReferences

- Reymond, A.; Meroni, G.; Fantozzi, A.; Merla, G.; Cairo, S.; Luzi, L.; Riganelli, D.; Zanaria, E.; Messali, S.; Cainarca, S.; et al. The tripartite motif family identifies cell compartments. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 2140–2151.

- Meroni, G.; Diez-Roux, G. TRIM/RBCC, a novel class of ’single protein RING finger’ E3 ubiquitin ligases. Bioessays 2005, 27, 1147–1157.

- Komander, D.; Rape, M. The ubiquitin code. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2012, 81, 203–229.

- Williams, F.P.; Haubrich, K.; Perez-Borrajero, C.; Hennig, J. Emerging RNA-binding roles in the TRIM family of ubiquitin ligases. Biol. Chem. 2019, 400, 1443–1464.

- Hatakeyama, S. TRIM proteins and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011, 11, 792–804.

- Hatakeyama, S. TRIM Family Proteins: Roles in Autophagy, Immunity, and Carcinogenesis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2017, 42, 297–311.

- Di Rienzo, M.; Romagnoli, A.; Antonioli, M.; Piacentini, M.; Fimia, G.M. TRIM proteins in autophagy: Selective sensors in cell damage and innate immune responses. Cell Death Differ. 2020, 27, 887–902.

- Short, K.M.; Cox, T.C. Sub-classification of the rbcc/trim superfamily reveals a novel motif necessary for microtubule binding. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 8970–8980.

- Cainarca, S.; Messali, S.; Ballabio, A.; Meroni, G. Functional characterization of the Opitz syndrome gene product (midin): Evidence for homodimerization and association with microtubules throughout the cell cycle. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1999, 8, 1387–1396.

- Schweiger, S.; Foerster, J.; Lehmann, T.; Suckow, V.; Muller, Y.A.; Walter, G.; Davies, T.; Porter, H.; van Bokhoven, H.; Lunt, P.W.; et al. The Opitz syndrome gene product, MID1, associates with microtubules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 2794–2799.

- Meroni, G. TRIM E3 Ubiquitin Ligases in Rare Genetic Disorders. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 1233, 311–325.

- Sardiello, M.; Cairo, S.; Fontanella, B.; Ballabio, A.; Meroni, G. Genomic analysis of the TRIM family reveals two groups of genes with distinct evolutionary properties. BMC Evol. Biol. 2008, 8, 225.

- Kitamura, K.; Tanaka, H.; Nishimune, Y. Haprin, a novel haploid germ cell-specific RING finger protein involved in the acrosome reaction. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 44417–44423.

- Balint, I.; Muller, A.; Nagy, A.; Kovacs, G. Cloning and characterisation of the RBCC728/TRIM36 zinc-binding protein from the tumor suppressor gene region at chromosome 5q22.3. Gene 2004, 332, 45–50.

- Kitamura, K.; Nishimura, H.; Nishimune, Y.; Tanaka, H. Identification of human HAPRIN potentially involved in the acrosome reaction. J. Androl. 2005, 26, 511–518.

- Singh, N.; Bhat, V.K.; Tiwari, A.; Kodaganur, S.G.; Tontanahal, S.J.; Sarda, A.; Malini, K.V.; Kumar, A. A homozygous mutation in TRIM36 causes autosomal recessive anencephaly in an Indian family. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017, 26, 1104–1114.

- Miyajima, N.; Maruyama, S.; Nonomura, K.; Hatakeyama, S. TRIM36 interacts with the kinetochore protein CENP-H and delays cell cycle progression. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 381, 383–387.

- Gudimchuk, N.B.; McIntosh, J.R. Regulation of microtubule dynamics, mechanics and function through the growing tip. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 777–795.

- Tomonaga, T.; Matsushita, K.; Ishibashi, M.; Nezu, M.; Shimada, H.; Ochiai, T.; Yoda, K.; Nomura, F. Centromere protein H is up-regulated in primary human colorectal cancer and its overexpression induces aneuploidy. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 4683–4689.

- Cuykendall, T.N.; Houston, D.W. Vegetally localized Xenopus trim36 regulates cortical rotation and dorsal axis formation. Development 2009, 136, 3057–3065.

- Olson, D.J.; Oh, D.; Houston, D.W. The dynamics of plus end polarization and microtubule assembly during Xenopus cortical rotation. Dev. Biol. 2015, 401, 249–263.

- Mei, W.; Jin, Z.; Lai, F.; Schwend, T.; Houston, D.W.; King, M.L.; Yang, J. Maternal Dead-End1 is required for vegetal cortical microtubule assembly during Xenopus axis specification. Development 2013, 140, 2334–2344.

- Houston, D.W. Cortical rotation and messenger RNA localization in Xenopus axis formation. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Dev. Biol. 2012, 1, 371–388.

- Aoki, Y.; Tsujimura, A.; Kaseda, K.; Okabe, M.; Tokuhiro, K.; Ohta, T.; O’Bryan, M.K.; Okuda, H.; Kitamura, K.; Ogawa, Y.; et al. Haprin-deficient spermatozoa are incapable of in vitro fertilization. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2020, 87, 534–541.

- Bhide, P.; Sagoo, G.S.; Moorthie, S.; Burton, H.; Kar, A. Systematic review of birth prevalence of neural tube defects in India. Birth Defects Res. A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 2013, 97, 437–443.

- Copp, A.J.; Stanier, P.; Greene, N.D. Neural tube defects: Recent advances, unsolved questions, and controversies. Lancet Neurol. 2013, 12, 799–810.

- Michael D. Griswold; Spermatogenesis: The Commitment to Meiosis. Physiological Reviews 2016, 96, 1-17, 10.1152/physrev.00013.2015.

More

Information

Subjects:

Agriculture, Dairy & Animal Science

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

616

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

08 Feb 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No