Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CHUNYI WEN | + 1384 word(s) | 1384 | 2022-01-18 06:45:20 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 1384 | 2022-02-07 09:38:02 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Wen, C. COVID-19 and Musculoskeletal Dysfunction. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19133 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Wen C. COVID-19 and Musculoskeletal Dysfunction. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19133. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Wen, Chunyi. "COVID-19 and Musculoskeletal Dysfunction" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19133 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Wen, C. (2022, February 07). COVID-19 and Musculoskeletal Dysfunction. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19133

Wen, Chunyi. "COVID-19 and Musculoskeletal Dysfunction." Encyclopedia. Web. 07 February, 2022.

Copy Citation

Although coronaviral infections are mainly linked to respiratory symptoms, skeletal-related risks and complications are also identified.

long-COVID

osteoarthritis

1. Osteoarticular Changes in COVID-19 Patients

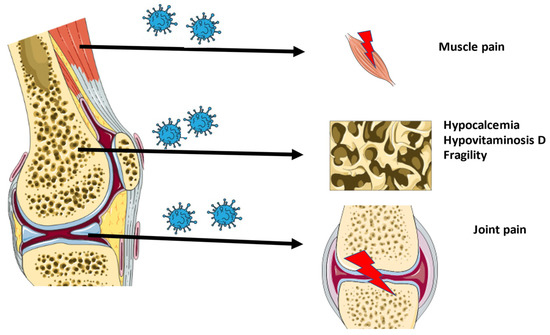

Although coronaviral infections are mainly linked to respiratory symptoms, skeletal-related risks and complications are also identified. In 2003, SARS-CoV-1 patients presented with osteonecrosis and reduced bone mass, although these symptoms were mainly attributed to the steroid-based therapy [1]. Today, an osteo-metabolic phenotype of COVID-19 has been characterized, including hypocalcemia, chronic hypovitaminosis D, and a high prevalence of bone fragility. This phenotype is associated with a more severe form of the disease and higher mortality [2][3][4]. It was originally categorized as an endocrine/metabolic phenotype, since a link between COVID-19 and endocrine organs and tissues was easily established after observing a higher mortality in patients suffering metabolic diseases, such as diabetes or obesity. The effect on bone and the mineral metabolism was later defined, and subsequently renamed to the osteo-metabolic phenotype. Hypocalcemia was first observed in a thyroidectomized patient [5]. Following this first report, hypocalcemia was reported in 62.6% to 87.2% of COVID-19 patients, depending on the definition criteria [3]. It corresponds with increased markers for inflammation and thrombosis, a higher need for hospitalization, and increased mortality. The low calcium levels are related to acute malnutrition, the actions of the virus, and hypovitaminosis D [3][4]. Additionally, it is hypothesized that a vitamin D deficiency not only influences hypocalcemia, but also poses a higher risk for more severe disease and increased susceptibility to a SARS-CoV-2 infection on its own. In a randomized observational trial, researchers observed that COVID-19 patients had a high prevalence of hypovitaminosis D, and that these patients have a significantly higher mortality risk [6]. The effects of vitamin D are mainly attributed to the immunomodulatory role of vitamin D on the immune system [7][8]. Immobilization due to the bedrest associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection or due to lockdown and quarantine, in combination with vitamin D deficiency and hypocalcemia, can lead to bone demineralization

2. Musculoskeletal Pain in COVID-19 Patients

Large joint arthralgia in the knee, ankles, shoulder, wrist, and hip was observed in 50% of patients 6 months after SARS-CoV-1 infection. Since no abnormalities could be observed on MRI, it was postulated that the pain was either of neurogenic origin or linked to low-grade synovitis, which could not be observed on MRI. The non-specific joint pain persisted in these patients 2 to 4 years after the initial SARS-CoV-1 infection [1]. Moreover, muscle weakness and myopathy, including myofiber necrosis or atrophy, were also detected in SARS-CoV-1 patients. It was postulated to be immune-mediated, attributed to critical illness, or steroid-induced myopathy [9][10].

Joint pain and myalgia are also common characteristics of COVID-19. The pain develops during the acute phase of the disease and is observed in 25 to 50% of patients. It has been demonstrated that at the onset of SARS-CoV-2 infection, myalgia is associated with a higher chance of developing post-COVID syndrome and the presence of post-COVID musculoskeletal symptoms. In the latter case, the pain of the acute phase does not disappear and becomes an important characteristic of long-COVID [11][12][13][14][15]. Several longitudinal studies conducted in Turkey, France, and Italy followed COVID-19 patients 6 months after discharge. After 6 months, around 60% of patients were still suffering from at least one SARS-CoV-2 related symptom. The most common were fatigue, myalgia, and joint pain with average prevalence of 30%, 20%, and 15% respectively [16][17]. In the majority of patients (65%), joint pain and myalgia were widespread throughout the body. A minority of patients had local joint pain mainly found in the knee, foot-ankle, and shoulder, while local myalgia was observed in the lower leg, arm, and shoulder. Surveys suggest that around 4.6% to 12.1% of patients still suffer from joint pain during the first year after infection [18]. Long-COVID pain has been demonstrated to be associated with fatigue and is more prevalent to occur in women [19].

An overview of the musculoskeletal ageing characteristics of long-COVID is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Overview of the musculoskeletal characteristics of long-COVID.

3. Will COVID-19 Lead to Viral Arthritis?

Several cases of viral arthritis after a SARS-CoV-2 infection have been reported. However, the total number of reported cases compared to the total number of COVID-19 patients is limited, indicating that viral arthritis is a rare complication of the disease. Case studies revealed an early onset of the arthritis days after a severe acute infection, which is cured by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) treatment. This complication mostly occurs in males and targets the lower limbs [20][21][22]. It is hypothesized that in severe cases, SARS-CoV-2 induces an auto-immune response causing arthritis.

In most viral arthritis cases, the virus was not found in the synovial fluid. Recent studies also showed no presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the joint of COVID-19 cadavers after analyzing the synovial fluid, synovial membrane, and bone via real-time polymerase chain reaction [23]. In contrast, one study of a non-hospitalized medium ill patient found traces of nucleic acids of SARS-CoV-2 in the joint [24]. In general, this points to a non-immediate role of SARS-CoV-2 in the onset of musculoskeletal changes after a SARS-CoV-2 infection.

In conclusion, the osteoarticular symptoms and musculoskeletal pain of patients with long-COVID closely resemble early aging characteristics associated with osteoarthritis (OA). These symptoms are probably not connected to viral arthritis, as the prevalence is much higher. The absence of viral RNA in the joint suggests an indirect effect of SARS-CoV-2 on the joint.

4. New Approach in Treating Long-COVID: The Role of the Nicotinic Cholinergic Receptor

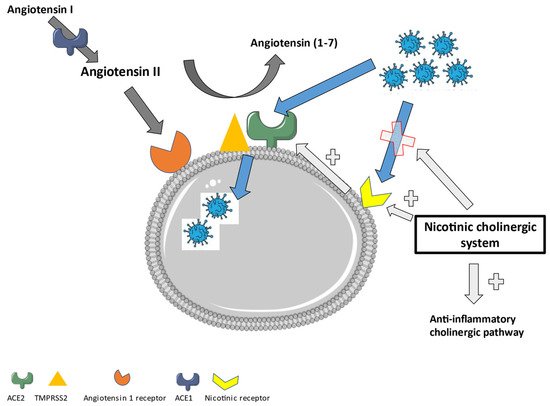

Most studies investigating the role of ACE2 show an increased expression in the lungs of smokers or patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [25][26][27][28]. This has been attributed to inflammation and the nicotinic cholinergic system. First, smoking and COPD induce inflammation, which can cause an upregulation of ACE2. Secondly, nicotine itself was shown to increase the ACE2 expression in human bronchial epithelial cells. This effect was reduced after the administration of alfa-bungarotoxin, a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) antagonist [29]. Additionally, the gene expression of ACE2 showed a positive correlation with the gene for the nicotinic Alpha 7 subunit of the cholinergic receptor (CHRNA7) (Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.54) [30]. This points further to a direct role of nicotine in the upregulation of ACE2. The higher enzymatic activity of ACE2 after nicotine administration reduces the amount of angiotensin II in favor of Angiotensin (1–7) [31], which will then promote the anti-inflammatory pathways. Moreover, the administration of nicotine could stimulate the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway through the alfa7-nAchR and the vagal nerve [32][33]. This points to a role for nicotine or nicotinic receptor agonists in the treatment of inflammatory diseases, including viral infections such as COVID-19.

Additionally, nicotine itself can act as a competitive antagonist for the direct interaction of SARS-CoV-2 with the nAchR. It has been proven that an amino acid sequence in the receptor-binding domain of the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 is similar to alfa-bungarotoxin and therefore is a good match for the alfa 7 and alfa 9 receptor [34]. The SARS-CoV-2 interaction with the nicotinic receptor will inhibit the nicotinic cholinergic system and dysregulate the Angiotensin II/Angiotensin (1–7) balance in favor of the pro-inflammatory status. The administration of nicotine could counteract this interaction and lower the angiotensin II expression. This further confirms that nicotine could form an interesting therapy to treat COVID-19.

It needs to be noticed that the dominant negative duplicate CHRFAM7A, the human partial duplication of the CHRNA7 gene which encodes for the α7nAchR, is decreased in patients with a more severe form of COVID-19. A reduced CHRFAM7A expression increases the ion channel function and stimulates the anti-inflammatory effect [35]. This needs to be taken into account when considering treatment strategies, as it has proven to interfere with nicotine-based therapy in the past [36]. In contrast, some studies also estimated a potential influence of nicotine on the development of COVID-19 [37]. More studies are required to further clarify its exact role.

The nicotinic cholinergic system also plays an important role in joint pain and dysfunction, as observed in the OA pathology [38]. The classical cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway was recently evaluated to reduce OA-related inflammation [39]. Additionally, the cholinergic system influences the different substructures of the joint attenuating the OA-related dysfunction. The cholinergic system stimulates chondrocyte proliferation, early mineralization, and delays differentiation. It restores the subchondral bone structure through osteoblast proliferation and osteoclast apoptosis [38]. Therefore, attenuating COVID-19 through the nicotinic cholinergic system could also improve its associated OA-like phenotype.

In Figure 2, an overview of the role of the nicotinic cholinergic system in a SARS-CoV-2 infection is displayed.

Figure 2. The role of the nicotinic cholinergic system in a SARS-CoV-2 infection.

References

- Griffith, J.F. Musculoskeletal complications of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Semin. Musculoskelet. Radiol. 2011, 15, 554–560.

- di Filippo, L.; Frara, S.; Giustina, A. The emerging osteo-metabolic phenotype of COVID-19: Clinical and pathophysiological aspects. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2021, 17, 445–446.

- di Filippo, L.; Doga, M.; Frara, S.; Giustina, A. Hypocalcemia in COVID-19: Prevalence, clinical significance and therapeutic implications. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2021, 1–10.

- Puig-Domingo, M.; Marazuela, M.; Yildiz, B.O.; Giustina, A. COVID-19 and endocrine and metabolic diseases. An updated statement from the European Society of Endocrinology. Endocrine 2021, 72, 301–316.

- Bossoni, S.; Chiesa, L.; Giustina, A. Severe hypocalcemia in a thyroidectomized woman with COVID-19 infection. Endocrine 2020, 68, 253–254.

- Carpagnano, G.E.; Di Lecce, V.; Quaranta, V.N.; Zito, A.; Buonamico, E.; Capozza, E.; Palumbo, A.; Di Gioia, G.; Valerio, V.N.; Resta, O. Vitamin D deficiency as a predictor of poor prognosis in patients with acute respiratory failure due to COVID-19. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2021, 44, 765–771.

- Kumar, R.; Rahthi, H.; Haq, A.; Wimalawansa, S.J.; Sharma, A. Putative roles of vitamin D in modulating immune response and immunopathology associated with COVID-19. Virus Res. 2020, 292, 198235.

- Hadizadeh, F. Supplementation with vitamin D in the COVID-19 pandemic? Nutr. Rev. 2021, 79, 200–208.

- Leung, T.W.; Wong, K.S.; Hui, A.C.; To, K.F.; Lai, S.T.; Ng, W.F.; Ng, H.K. Myopathic changes associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome: A postmortem case series. Arch. Neurol. 2005, 62, 1113–1117.

- Tsai, L.-K.; Hsieh, S.-T.; Chang, Y.-C. Neurological manifestations in severe acute respiratory symptom. Acta Neurol. Taiwan. 2005, 14, 113–119.

- Vehar, S.; Boushra, M.; Ntiamoah, P.; Biehl, M. Post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection: Caring for the ‘long-haulers’. Cleve. Clin. J. Med. 2021, 88, 267–272.

- Aiyegbusi, O.L.; Hughes, S.E.; Turner, G.; Rivera, S.C.; McMullan, C.; Chandan, J.S.; Haroon, S.; Price, G.; Davies, E.H. Symptoms, complications and management of long COVID: A review. J. R. Soc. Med. 2021, 114, 428–442.

- Tosato, M.; Carfì, A.; Martis, I.; Pais, C.; Ciciarello, F.; Rota, E.; Tritto, M.; Salerno, A.; Zazzara, M.B.; Martone, A.M.; et al. Prevalence and Predictors of Persistence of COVID-19 Symptoms in Older Adults: A Single-Center Study. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 1840–1844.

- Tuzun, S.; Keles, A.; Okutan, D.; Yildiran, T.; Palamar, D. Assessment of musculoskeletal pain, fatigue and grip strength in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2021, 57, 653–662.

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Rodríguez-Jiménez, J.; Fuensalida-Novo, S.; Palacios-Ceña, M.; Gómez-Mayordomo, V.; Florencio, L.L.; Hernández-Barrera, V.; Arendt-Nielsen, L. Myalgia as a symptom at hospital admission by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection is associated with persistent musculoskeletal pain as long-term post-COVID sequelae: A case-control study. Pain 2021, 162, 2832–2840.

- Ghosn, J.; Piroth, L.; Epaulard, O.; Le Turnier, P.; Mentr, F.; Covid, F. Persistent COVID-19 symptoms are highly prevalent 6 months after hospitalization: Results from a large prospective cohort. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, 1041.

- Karaarslan, F.; Güneri, F.D.; Kardeş, S. Long COVID: Rheumatologic/musculoskeletal symptoms in hospitalized COVID-19 survivors at 3 and 6 months. Clin. Rheumatol. 2022, 41, 289–296.

- Fernández-de-las-Peñas, C.; Navarro-Santana, M.; Plaza-Manzano, G.; Palacios-Ceña, D.; Arendt-Nielsen, L. Time Course Prevalence of Post-COVID Pain Symptoms of Musculoskeletal Origin in Patients Who Had Survived to SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Pain 2021.

- Sykes, D.L.; Holdsworth, L.; Jawad, N.; Gunasekera, P.; Morice, A.H.; Crooks, M.G. Post-COVID-19 Symptom Burden: What is Long-COVID and How Should We Manage It? Lung 2021, 199, 113–119.

- Gasparotto, M.; Framba, V.; Piovella, C.; Doria, A.; Iaccarino, L. Post-COVID-19 arthritis: A case report and literature review. Clin. Rheumatol. 2021, 40, 3357–3362.

- Kocyigit, B.F.; Akyol, A. Reactive arthritis after COVID-19: A case-based review. Rheumatol. Int. 2021, 41, 2031–2039.

- Ono, K.; Kishimoto, M.; Shimasaki, T.; Uchida, H.; Kurai, D.; Deshpande, G.A.; Komagata, Y.; Kaname, S. Reactive arthritis after COVID-19 infection. RMD Open 2020, 6, 2–5.

- Grassi, M.; Giorgi, V.; Nebuloni, M.; Gismondo, M.R.; Salaffi, F.; Sarzi-Puttini, P.; Rimoldi, S.G.; Manzotti, A. SARS-CoV-2 in the knee joint: A cadaver study. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2021. online ahead of print.

- Kuschner, Z.; Ortega, A.; Mukherji, P. A case of SARS-CoV-2-associated arthritis with detection of viral RNA in synovial fluid. J. Am. Coll. Emerg. Physicians Open 2021, 2, 22–24.

- Leung, J.M.; Yang, C.X.; Tam, A.; Shaipanich, T.; Hackett, T.L.; Singhera, G.K.; Dorscheid, D.R.; Sin, D.D. ACE-2 expression in the small airway epithelia of smokers and COPD patients: Implications for COVID-19. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 55, 2000688.

- Cai, G.; Bossé, Y.; Xiao, F.; Kheradmand, F.; Amos, C.I. Tobacco smoking increases the lung gene expression of ACE2, the Receptor of SARS-CoV-2. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 201, 1557–1559.

- Zhang, H.; Rostami, M.R.; Leopold, P.L.; Mezey, J.G.; O’Beirne, S.L.; Strulovici-Barel, Y.; Crystal, R.G. Expression of the SARS-CoV-2 ACE2 receptor in the human airway epithelium. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 202, 219–229.

- Jacobs, M.; van Eeckhoutte, H.P.; Wijnant, S.R.A.; Janssens, W.; Joos, G.F.; Brusselle, G.G.; Bracke, K.R. Increased expression of ACE2, the SARS-CoV-2 entry receptor, in alveolar and bronchial epithelium of smokers and COPD subjects. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 56, 2002378.

- Russo, P.; Bonassi, S.; Giacconi, R.; Malavolta, M.; Tomino, C.; Maggi, F. COVID-19 and smoking: Is nicotine the hidden link? Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 55, 2001116.

- Leung, J.; Yang, C.; Sin, D. COVID-19 and nicotine as a mediator of ACE-2. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 55, 2001261.

- Di Maro, M.; Cataldi, M.; Santillo, M.; Chiurazzi, M.; Damiano, S.; De Conno, B.; Colantuoni, A.; Guida, B. The Cholinergic and ACE-2-Dependent Anti-Inflammatory Systems in the Lung: New Scenarios Emerging From COVID-19. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 653985.

- Gauthier, A.G.; Lin, M.; Wu, J.; Kennedy, T.P.; Daley, L.A.; Ashby, C.R., Jr.; Mantell, L.L. From nicotine to the cholinergic anti-inflammatory reflex–Can nicotine alleviate the dysregulated inflammation in COVID-19? J. Immunotoxicol. 2021, 18, 23–29.

- Qin, Z.; Xiang, K.; Su, D.F.; Sun, Y.; Liu, X. Activation of the Cholinergic Anti-Inflammatory Pathway as a Novel Therapeutic Strategy for COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11, 595342.

- Farsalinos, K.; Eliopoulos, E.; Leonidas, D.D.; Papadopoulos, G.E.; Tzartos, S.; Poulas, K. Nicotinic cholinergic system and COVID-19: In silico identification of an interaction between SARS-CoV-2 and nicotinic receptors with potential therapeutic targeting implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5807.

- Sinkus, M.L.; Graw, S.; Freedman, R.; Ross, R.G.; Lester, H.A.; Leonard, S. The human CHRNA7 and CHRFAM7A genes: A review of the genetics, regulation, and function. Neuropharmacology 2015, 96, 274–288.

- Courties, A.; Boussier, J.; Hadjadj, J.; Yatim, N.; Barnabei, L.; Péré, H.; Veyer, D.; Kernéis, S.; Carlier, N.; Pène, F.; et al. Regulation of the acetylcholine/α7nAChR anti-inflammatory pathway in COVID-19 patients. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11886.

- Lupacchini, L.; Maggi, F.; Tomino, C.; De Dominicis, C.; Mollinari, C.; Fini, M.; Bonassi, S.; Merlo, D.; Russo, P. Nicotine Changes Airway Epithelial Phenotype and May Increase the SARS-CoV-2 Infection Severity. Molecules 2020, 26, 101.

- Lauwers, M.; Courties, A.; Sellam, J.; Wen, C. The cholinergic system in joint health and osteoarthritis: A narrative-review. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2021, 29, 643–653.

- Courties, A.; Sellam, J.; Berenbaum, F. Role of the autonomic nervous system in osteoarthritis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Rheumatol. 2017, 31, 661–675.

More

Information

Subjects:

Infectious Diseases

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

652

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

07 Feb 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No