You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ankit Dhamija | + 1911 word(s) | 1911 | 2021-11-29 07:50:49 | | | |

| 2 | Vivi Li | Meta information modification | 1911 | 2022-02-07 07:04:12 | | | | |

| 3 | Vivi Li | Meta information modification | 1911 | 2022-02-10 08:59:28 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Dhamija, A. Minimally Invasive Surgery of the Thymus. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19127 (accessed on 23 December 2025).

Dhamija A. Minimally Invasive Surgery of the Thymus. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19127. Accessed December 23, 2025.

Dhamija, Ankit. "Minimally Invasive Surgery of the Thymus" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19127 (accessed December 23, 2025).

Dhamija, A. (2022, February 07). Minimally Invasive Surgery of the Thymus. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19127

Dhamija, Ankit. "Minimally Invasive Surgery of the Thymus." Encyclopedia. Web. 07 February, 2022.

Copy Citation

The trend for thymoma surgery has been to increase utilization of minimally invasive options for resection; however, the primary objective should be to perform an oncological resection. One must consider the stage of tumor, presence of myasthenia gravis, presence of lymphadenopathy, and size of thymoma prior to deciding optimum surgical strategy.

thymus

myasthenia gravis

surgery

1. Definition of Minimally Invasive Surgery

The thymus has been of interest to surgeons for more than a hundred years. The extent of surgery has ranged from complete resection of thymic, mediastinal and neck fatty tissue, to resection of only tumor itself. The choice of approach to thymic surgery has been subject to constant controversy due to the improvements in visualization and advancement in technology in the last 20 years.

In the early era of surgery, transcervical and transsternal approaches provided satisfactory exposure. Since then, thymic surgery has been described with different incisions, exposures, and equipment. Incisions are named by anatomic location such as transcervical, extended transcervical, right or left thoracic, and subxiphoid. Technology-related approaches using these incisions have included video assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) and robotic options [1]. There are, nevertheless, various combinations of these techniques reported, such as joint VATS and transcervical, joint transcervical and subxiphoid, joint subxiphoid and VATS, and a combination of subxiphoid robotic surgery with bilateral chest incisions. Additionally, the technique of sternal lifting or soft tissue retraction has also been described. To help consolidate the terminology, the International Thymic Malignancy Interest Group (ITMIG) has defined minimally invasive thymectomy as any approach without a sternotomy (including partial sternotomy) or rib-spreading [2].

2. Extent of Resection

A simple thymectomy is defined as the complete removal of the thymus, en bloc, without violation of its capsule. When the thymus and thymoma are resected in their entirety, the operation is termed “thymothymectomy”. Where only the thymoma is removed, and thymus gland is left behind, the operation is referred to as a “thymomectomy”. An extended thymectomy includes a thymothymectomy along with resection of mediastinal fatty tissue, pericardial fatty tissue, and bilateral mediastinal pleura en bloc. Moreover, under certain circumstances, a radical or maximal thymectomy may be the procedure of choice. This requires an additional neck incision to access yet more fatty tissue surrounding the carotid artery and trachea. To date, no interinstitutional consensus for surgical management of thymic malignancies exists. In researchers' hands, a complete thymoma surgery refers to the removal of the thymus, thymoma, and fatty mediastinal tissue in its entirety, en bloc [2]. “Shelling out” thymic epithelial tumors (TETs) from the surrounding thymus and fatty tissue is not recommended, as microscopic transcapsular invasion is difficult to detect intraoperatively. Therefore, it is more preferable to obtain a large margin of resection from the perceived extent of the capsule [2]. That being said, there are numerous reports in the field of minimally invasive thymoma surgery claiming successful outcomes of thymoma resection only (thymomectomy). As such, there is ongoing debate regarding this topic [3][4].

In early thymomas, Masaoka Stage 1 and 2, the extent of resection should include mediastinal fat and bilateral pleura en bloc [5][6][7]. Thymic surgery is guided by the informal consensus drawn from expert recommendations and guidelines because case-control series and prospective randomized trials are lacking. In 2010, Masaoka himself provided interesting anecdotal reports [8]. By comparing his previous experiences at two different hospitals, he observed that overall survival rates in patients with Stage I and II thymomas undergoing extended thymothymectomy was superior to patients in the thymomectomy series (10-year survival rates of Stage I: 87.1% vs. 66.0%, those of Stage II: 80.6% vs. 60.0%). He attributed survival differences to the surgical oncological techniques used, as he performed different operations at each hospital.

There are many reasons to perform an extended thymoma resection:

-

Possibility of multicentric thymoma development.

-

Possibility of myasthenia gravis (MG) development in the subsequent years if only a thymectomy is performed. Post-thymectomy MG has been shown to correlate with higher levels of Acetylcholine Receptor antibodies (ARab), which tend to correlate with myasthenic symptoms [9][10]. Regardless of whether ARab levels are elevated or not, researchers' preference is to perform an extended thymothymectomy.

-

To decrease the risk of local recurrences.

-

Control of conditions such as pure red cell aplasia and hypogammaglobulinemia.

3. Difficult Decisions and Common Errors

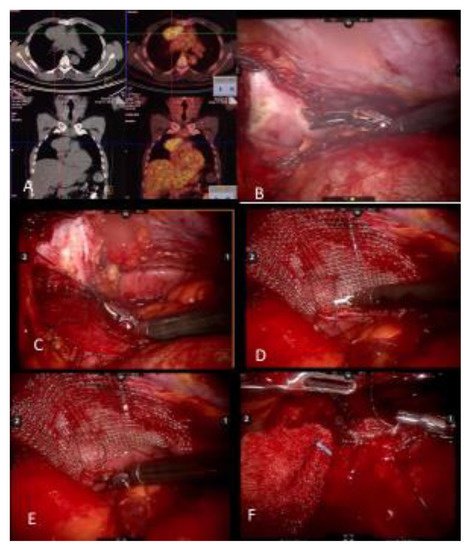

Prior reports claim that extensive pleural adhesions, pericardial adhesions, great vessel involvement, and pericardial involvement are contraindications to minimally invasive thymoma resections [2]. In researchers' experience, however, it is rare for thymic masses to involve the superior vena cava or right innominate vein. On the contrary, left innominate vein involvement is more common. Researchers have also found that complete resection of the left innominate vein is feasible without reconstruction if the patient does not have a history of a radical neck dissection for a neck tumor [11]. Pericardial resection has been previously considered a contraindication to minimally invasive surgery for thymoma, but researchers have demonstrated technical feasibility despite pericardial involvement, using both the robotic console and VATS approach (Figure 1).

Figure 1. (A) Noncontrast CT of a myasthenia gravis patient with a thymoma and PET CT demonstrating FDG uptake. (B) Pericardial resection using the robotic bipolar instrument. (C) Invasion of pericardium may be deep in the left chest and may require upward traction up the pericardium. It is important to identify and preserve the left phrenic nerve from medial and internal side of the pericardium. (D) When reconstructing the pericardium with a graft, the first suture placed allows upward traction of the hilar pericardium. (E) A continuous suture technique with barbed sutures is preferred when reconstructing the pericardium. (F) As the left hilar pericardium is pulled up, attention should be given to not place the graft too tight as to constrict the heart.

Not only is it important to keep the specimen en bloc upon resection, but for the same reasons it is important to extract the tumor from the patient without perforation or spillage. Therefore, the size of incision necessary to extract the tumor may determine the feasibility of a minimally invasive or open approach. In addition to size, the extent of invasiveness is a factor to consider while deciding surgical approach. Some tumors may be small but are still considered invasive. Researchers have demonstrated that Masaoka Stage I and II thymomas are ideal candidates for minimally invasive thymoma resection and that Masaoka Stage rather than the thymoma size is a more important prognostic factor [12].

4. Myasthenia Gravis

Patients with MG are considered separate entities when discussing the nuances of surgical technique. First, the duration of surgery is important for patients with MG whereas patients without MG do not have the same time limitations. Longer operative times potentially increase MG-related postoperative complications such as myasthenic crisis, atelectasis, and pneumonia. Surgeon expertise is one of the most important factors that influences duration of surgery. This becomes increasingly relevant when resection and reconstruction of vital structures may prolong surgical time. Secondly, in patients with Masaoka Stage III, and in some patients with Masaoka Stage II disease, phrenic nerve, lung, pericardial, or pleural resections may be needed. Even when there is no invasion into these structures in Masaoka Stage II, greater experience in minimally invasive techniques may be required to prevent unnecessary collateral damage [13].

The oncological and neurological outcomes of MG patients and thymoma have been studied after robotic surgery [14]. In a series by Romano et al., patients who had their thymus removed showed a complete stable remission (CSR) rate of 14.7% at three years and a clinical improvement in 77% of patients with MG. Conversely, 23.6% experienced either no substantial change or worsened symptoms. The average operation duration was 126 min, and the average hospital stay was 5.1 days [14]. This length of stay (LOS) with robotic surgery is a clear example of the outcome of prolonged surgical time.

In a prior report, researchers have demonstrated that the duration of surgery is the single, most important factor for determining next morning discharge in patients with MG who underwent thymectomy [15]. Of the patients discharged the following morning, the mean operative time was 42 min, and the patients with a longer LOS had a mean operative time of 55 min [15]. A recent study published a median LOS of 3 days for minimally invasive thymic surgery and four days for open surgery. When performing thymoma resection in MG patients with a robotic, minimally invasive approach, the LOS has been shown to be even shorter [16]. If enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols are applied, open surgery patients have been shown to be discharged within three days. Kumar et al., analyzed outcomes after robotic thymoma resections and found that resection of surrounding structures, conversion to open surgery and postoperative complications were significantly higher in MG patients [17]. In patients with MG and thymoma, the aim should be to decrease the operative time and achieve the highest oncologic quality. The operative approach is left to the discretion of the surgeon and is usually determined by level of expertise and severity of disease.

5. Lymph Node Dissection

Thymoma has been reported as one of the most common anterior mediastinal masses with a present, but very low rate of mediastinal lymph node metastasis. Approximately 90% of the involved nodes are located in the anterior mediastinum and there has been a trend towards removing the anterior mediastinal nodes routinely, as recommended by ITMIG [18]. A more extensive nodal assessment may be indicated in higher stage thymomas [18]. A recently published study discussed the importance of a routine mediastinal and cervical lymph node dissection in particular tumors, such as thymic carcinoids and thymic carcinoma [19].

Kondo and Monden were the first to report the incidence of lymph node positivity and its effect on prognosis in patients with thymoma, thymic carcinoma, and thymic carcinoid [20][21]. The rate of lymphogenous metastasis in thymoma, thymic carcinoma, and thymic carcinoid was found to be 1.8%, 27%, and 28%, respectively [21]. A large database of patients from the United States demonstrated the incidence and prognostic significance of nodal metastases in patients specifically with thymoma as high as 13.3% [22]. In 2013, Park recommended routine resection of all mediastinal lymph nodes in patients undergoing thymic resection, and ITMIG along with the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, have proposed a new TNM staging classification emphasizing the importance of lymph node status [19][23]. However, the debate remains regarding benefit of lymphadenectomy [24]. Of note, the mediastinum is a complex part of the thorax. Many histologically different neoplasms may arise from the multiple anatomic structures, and lymph nodes may harbor the metastases secondary to lesions in other parts of the body.

Today, lymph node dissection during minimally invasive surgery may seem unsatisfactory in comparison to open techniques. With the minimally invasive techniques of robotic surgery or VATS, accessible lymph nodes may be limited to the local anterior mediastinum. Therefore, the approach may be guided by the lymph nodes that need to be assessed. A left sided approach will allow access to lymph nodes at the aortopulmonary window and paraaortic region. Similarly, a right-sided approach, will allow access to the right paratracheal region. When performing the subxiphoid approach, both lymph node basins may be accessed. By adding a cervical incision to the subxiphoid approach, a complete lymph node dissection may be possible.

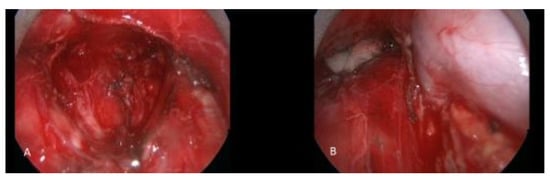

In researchers' experience, if the final pathologic diagnosis of a thymic tumor performed in a minimally invasive fashion is thymic carcinoma, researchers subsequently perform a cervical video-assisted mediastinal lymphadenectomy to stage and evaluate for micro-metastatic disease after performing a PET-CT (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A patient with thymic carcinoma with suspicious mediastinal lymph node metastasis underwent cervical video mediastinoscopy and excision of the mediastinal lymph nodes. (A) Subcarinal region after complete removal of lymph node packet. (B) Right paratracheal region. The azygos vein and superior vena cava are seen skeletonized after lymphadenectomy.

References

- Rückert, J.C.; Ismail, M.; Swierzy, M.; Sobel, H.; Rogalla, P.; Meisel, A.; Wernecke, K.D.; Rückert, R.I.; Müller, J.M. Thoraco-scopic thymectomy with the da Vinci robotic system for myasthenia gravis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1132, 329–335.

- Toker, A.; Sonett, J.; Zielinski, M.; Rea, F.; Tomulescu, V.; Detterbeck, F.C. Standard terms, definitions, and policies for minimally ınvasive resection of thymoma. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2011, 6 (Suppl. 3), S1739–S1742.

- Huang, J.; Ahmad, U.; Antonicelli, A.; Catlin, A.C.; Fang, W.; Gomez, D.; Loehrer, P.; Lucchi, M.; Marom, E.; Nicholson, A.; et al. Development of the ınternational thymic malignancy ınterest group ınternational database: An unprecedented resource for the study of a rare group of tumors. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2014, 9, 1573–1578.

- Ruffini, E.; Detterbeck, F.; Van Raemdonck, D.; Rocco, G.; Thomas, P.; Weder, W.; Brunelli, A.; Evangelista, A.; Venuta, F.; Khaled, A.; et al. Tumours of the thymus: A cohort study of prognostic factors from the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons database. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2014, 46, 361–368.

- Girard, N.; Ruffini, E.; Marx, A.; Faivre-Finn, C.; Peters, S.; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Thymic epithelial tumours: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26 (Suppl. 5), v40–v55.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Thymomas and Thymic Carcinomas (Version 1.2021). Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/thymic.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Falkson, C.B.; Bezjak, A.; Darling, G.; Gregg, R.; Malthaner, R.; Maziak, D.E.; Yu, E.; Smith, C.A.; McNair, S.; Ung, Y.C.; et al. The management of thymoma: A systematic review and practice guideline. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2009, 4, 911–919.

- Masaoka, A. Staging System of Thymoma. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2010, 5, S304–S312.

- Nakajima, J.; Murakawa, T.; Fukami, T.; Sano, A.; Takamoto, S.; Ohtsu, H. Postthymectomy myasthenia gravis: Rela-tionship with thymoma and antiacetylcholine receptor antibody. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2008, 86, 941–945.

- Ruffini, E.; Filosso, P.L.; Guerrera, F.; Lausi, P.; Lyberis, P.; Oliaro, A. Optimal surgical approach to thymic malignancies: New trends challenging old dogmas. Lung Cancer 2018, 118, 161–170.

- Toker, A.; Hayanga, J.A.; Dhamija, A.; Abbas, G. Superior vena cava reconstruction in mediastinal tumors. Am. J. Surg. 2021, 222, 294–296.

- Toker, A.; Erus, S.; Ziyade, S.; Özkan, B.; Tanju, S. It is feasible to operate on pathological masaoka stage I and II thymoma patients with video-assisted thoracoscopy: Analysis of factors for a successful resection. Surg. Endosc. 2012, 27, 1555–1560.

- Toker, A.; Kakuturu, J. Why robotic surgery for thymoma in patients with myasthenia gravis is not ‘one size fits all’. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2021, 60, 896–897.

- Romano, G.; Zirafa, C.C.; Ceccarelli, I.; Guida, M.; Davini, F.; Maestri, M.; Morganti, R.; Ricciardi, R.; Hung Key, T.; Melfi, F. Robotic thymectomy for thymoma in patients with myasthenia gravis: Neurological and oncological out-comes. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2021, 60, 890–895.

- Toker, A.; Tanju, S.; Ziyade, S.; Ozkan, B.; Sungur, Z.; Parman, Y.; Serdaroglu, P.; Deymeer, F. Early outcomes of vid-eo-assisted thoracoscopic resection of thymus in 181 patients with myasthenia gravis: Who are the candidates for the next morning discharge? Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2009, 9, 995–998.

- Kumar, A.; Goyal, V.; Asaf, B.B.; Trikha, A.; Sood, J.; Vijay, C.L. Robotic thymectomy for myasthenia gravis with or without thymoma-surgical and neurological outcomes. Neurol. India 2017, 65, 58–63.

- Kumar, A.; Asaf, B.B.; Pulle, M.V.; Puri, H.V.; Sethi, N.; Bishnoi, S. Myasthenia is a poor prognostic factor for periopera-tive outcomes after robotic thymectomy for thymoma. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2021, 59, 807–813.

- Detterbeck, F.C.; Moran, C.; Huang, J.; Suster, S.; Walsh, G.; Kaiser, L.; Wick, M. Which way is up? Policies and proce-dures for surgeons and pathologists regarding resection specimens of thymic malignancy. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2011, 6 (Suppl. 3), S1730–S1738.

- Detterbeck, F.C.; Stratton, K.; Giroux, D.; Asamura, H.; Crowley, J.; Falkson, C.; Filosso, P.L.; Frazier, A.A.; Giaccone, G.; Huang, J.; et al. The IASLC/ITMIG thymic epithelial tumors staging project: Proposal for an evidence-based stage classification system for the forthcoming (8th) edition of the TNM classification of ma-lignant tumors. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2014, 9 (Suppl. 2), S65–S72.

- Kondo, K.; Monden, Y. Therapy for thymic epithelial tumors: A clinical study of 1,320 patients from Japan. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2003, 76, 878–884.

- Kondo, K.; Monden, Y. Lymphogenous and hematogenous metastasis of thymic epithelial tumors. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2003, 76, 1859–1864.

- Weksler, B.; Pennathur, A.; Sullivan, J.L.; Nason, K.S. Resection of thymoma should include nodal sampling. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015, 149, 737–742.

- Park, I.K.; Kim, Y.T.; Jeon, J.H.; Kim, H.S.; Hwang, Y.; Seong, Y.W.; Kang, C.H.; Kim, J.H. Importance of lymph node dissec-tion in thymic carcinoma. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2013, 96, 1025–1032.

- Hsin, M.K.; Keshavjee, S. Should lymph nodes be routinely sampled at the time of thymoma resection? J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2015, 149, 743–744.

More

Information

Subjects:

Surgery

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

732

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

10 Feb 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No