There are several key scientific issues, these seven issues are hot research topics worthy of in-depth exploration in the future: the harmonizing of the definition of the concept of forest ecological assets; what should be the main focus of future research on forest ecological assets; the construction of an evaluation indicators system according to local conditions; the data assimilation methods of integrating ground-based positioning observations and space-based remote-sensing observations that complement each other; the study of the spatial and temporal heterogeneity of forest ecological assets; the study the net value of forest ecological assets; how to retain and increase the value of forest ecological assets; and how enhance the ecological carrying capacity of forests. These issues require further research.

1. Introduction

The research results of the United Nations “Millennium Ecosystem Assessment” project concluded that 15 of the 24 ecosystem service functions in the four major categories are continuously degrading, and 60% of the ecosystems on which humans depend are in a state of continuous degradation. Moreover, the increasing external pressures such as strong human interference and climate change will lead to the occurrence and development of desertification on a global scale

[1]. The first IPBES Global Assessment, released in 2019, reveals widespread accelerating declines in our planet’s biodiversity and life-support systems; this will threaten species viability, human security, physical and mental health, food, and livelihood security

[2]. This suggests that we need to pay more attention to natural ecosystems. As the main terrestrial ecosystem, forest is the largest and most widely distributed ecosystem on land, with the most complex composition and the most abundant material resources, and not only does it provide raw materials for human agricultural and industrial production, but more importantly, it supports and sustains the life- support system of the earth. Maintaining and conserving the forest ecosystem is the basis for achieving the sustainable development of the whole of society

[3][4].

Forests are complex and dynamic ecosystems that provide a wide range of ecological, economic, and sociocultural values to society. These values include many commodities and amenities such as water production, soil conservation, carbon sequestration, wildlife habitat, provision of forage, and a variety of wood products

[5]. Forests also provide a variety of cultural ecosystem services (ES), such as recreation, landscape aesthetics, or cultural heritage

[6]. In addition, they act as natural barriers to buffer the effects of climate change and natural disasters, such as windbreak and sand fixation, landslide and debris flow prevention, and flood mitigation

[7]. In recent years, special emphasis has been placed on the non-material values of forests. But regardless of the type of classification used, the tangible and intangible benefits that society derives from it. The services discussed here are not unique to forests and can be derived from other land covers/uses as well (though in smaller quantities).

As forest ecological assets (FEA) are not fully “captured” in commercial markets or quantified in the same way as economic services and manufacturing capital, they are often given too little weight in decision-making and the public is almost completely unaware of society’s dependence on forest ecosystems

[8]; such neglect may ultimately undermine the sustainability of humans in the biosphere

[9]. Revealing the value of FEA is a prerequisite for economic decision-making to maintain life-support functions

[10]. Valuation is necessary for an informed allocation of limited resources in order to maximize the benefits to society

[11]; if these factors are internalized in the decision-making process, it can strengthen the country’s economic justification for forest protection

[12]. Therefore, the valuation of FEA is the foundation for ensuring the coordinated development of ecosystems and socio-economic systems

[13].

In 1921, Parker and Burgess introduced the concept of ecological carrying capacity in the

Journal of Human Ecology, which means “the maximum limit of the existence of a certain number of individuals under certain environmental conditions (mainly the combination of ecological factors such as living space, nutrients and sunlight)”

[14]. The individuals here are not just people, but should also include other creatures, such as ducks

[15] and deer

[16]. The connotation of forest carrying capacity (FCC) includes two basic meanings. Firstly, it refers to the capacity of forest ecosystem, which is its self-sustaining and self-regulating capacity, and is the supporting part of forest carrying capacity. Secondly, it refers to the development capacity of the socio-economic subsystem in the forest ecosystem, which is the pressure part of FCC

[17]. The study of FCC is a requirement for sustainable forest development. Only by developing and utilizing forest resources within the scope of FCC can the sustainability of forests be ensured. Regional FCC is crucial to regional social and economic development

[18].

FEA indicate FCC

[19]. The subject of evaluation of FEA is people, and the evaluation of FEA is the evaluation of the driving force of sustainable development of human society supported by the natural environment. The development of FEA and its related research will reveal the principle of mutual influence and change between human economic and social development and the ecological environment, for example, the trade-off relationship between flood control and timber production, and prompt human beings to explore the sustainable development path of being resource-efficient, ecologically sound, economically sustainable, and socially harmonious in their practical activities

[20][21]. FEA are the basis for the formation of forest eco-benefits and gross ecosystem value

[22], and FEA accounting provides the basis for the proposal of strategies for improving FCC. Forest resources are important ecological assets that support human social development. Exploring the value accounting of FEA is of great significance to the rational use and effective protection of forest resources.

2. Annual Distribution of the Literature

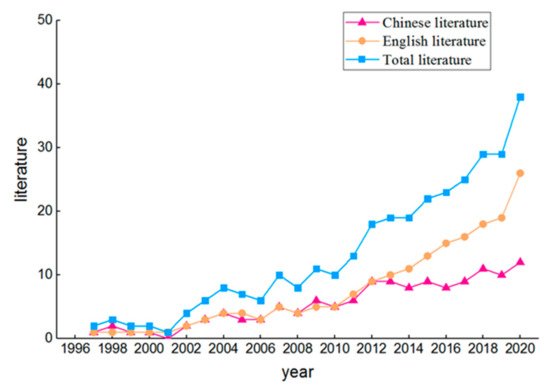

As shown in Figure 1, the annual distribution of the research literature on forest ecological assets can be roughly divided into three stages (Table 1). The first stage is from 1997 to 2001, the literature available is relatively small and the research is still at an embryonic stage with insufficient depth. Related research increased from 2002 to 2011, and many domestic scholars made their own insights on ecological assets—this phase was the growth phase. Between 2012 and 2020 is a period of rapid growth, with rapid development of ecological assets, ecosystem services, and ecological carrying capacity, and a gradual increase in integrated multidisciplinary research. Moreover, the trends of the English literature and the overall literature were basically the same.

Figure 1. Annual distribution of the literature.

Table 1. Division of research stages.

| Research Stage |

Research Content |

Development Background |

Main Characteristics |

| Embryonic Stage (1997–2001) |

Concept of ecological assets and selection of asset accounting indicators. |

The relevant theoretical research is still in the embryonic stage, and the research depth is insufficient. |

Less literature was found and was mostly for large-scale ecological asset accounting. |

| Growth Stage (2002–2011) |

The concept of ecological assets was first used more frequently, and the research has gradually deepened. |

Ecosystem quality is being emphasized globally across disciplines, and research on ecosystem services and ecological assets continues to diversify. |

Relevant articles are published every year, and the depth of research has deepened, with research on both the total value of regional ecological assets and the value of single ecosystem service functions. |

| Rapid-Growth Stage (2012–Today) |

Ecological asset accounting method and case study and ecological compensation. |

Ecological assets, ecosystem services, and ecological compensation are developing rapidly, and multidisciplinary integrated research is gradually increasing. |

There are many articles published every year and the research on ecological assets and carrying capacity is relatively mature, but there is no empirical research on small- and medium-scale study areas. |

3. Country Distribution of the Literature

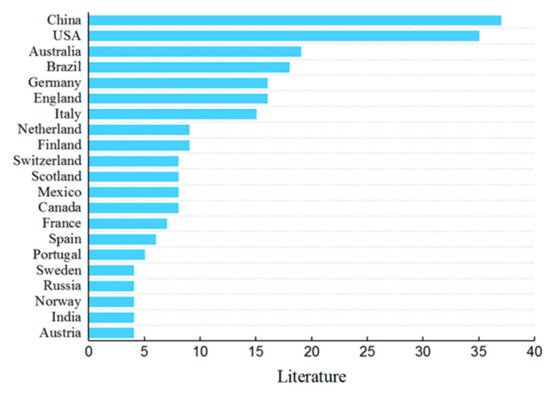

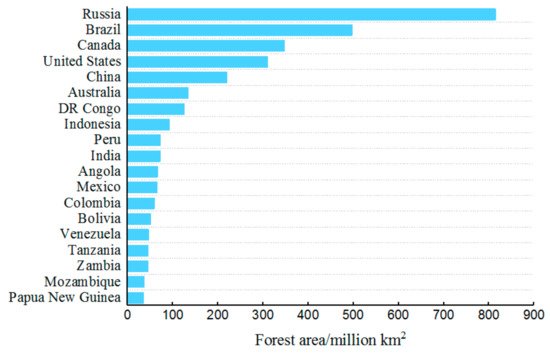

The country distribution of the literature is illustrated in Figure 2. Due to space limitations, only areas with four or more research articles are listed. China and the United States have the most research on forest ecological assets, accounting for 30% of the total, followed by Australia and Brazil, with 8% and 7%, respectively, and there are also more studies on Canada, Mexico, Scotland, Switzerland, Finland, Netherland, Italy, England, and Germany. Comparing the forest areas of the countries in the world (Figure 3), we find that countries with large forest areas such as DR Congo and Indonesia do not appear in Figure 2; instead, many European countries with small forest areas such as England and Italy are represented. This may indicate that interest is not linearly related to presence, but to perceived scarcity. On the other hand, there are more studies in developed countries than in developing countries.

Figure 2. Literature by country and territory.

Figure 3. World forest area in 2020: top 20 countries (data from FAO official database).

4. Literature Keywords Mapping

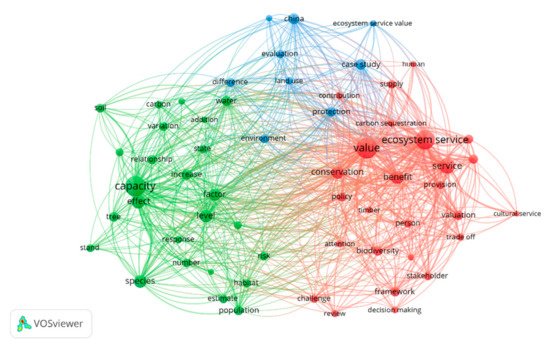

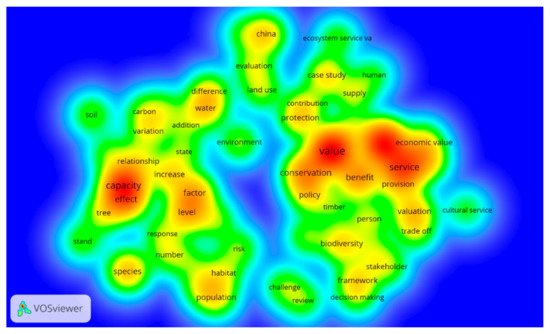

Keywords carry the most important and core information, and the analysis of keywords helps to understand the research hotspots in the field. The literature keywords were analyzed by the VOSviewer software, and the co-occurrence frequency was set greater than 10 times to obtain Figure 4 and Figure 5. Figure 4 shows the keywords clustering map. Cluster 1 (green) is centered on carrying capacity, effect, species, population, relationship et al. as secondary studies. Cluster 2 (red) is centered on ecosystem service and value, with conservation, benefit, policy, biodiversity, and supply et al., as secondary research. Cluster 3 (blue) is focused on China, evaluation, case study, and protection et al.; Figure 5 shows the keyword density mapping. The colors range from cool (blue) to warm (red) indicating that the higher the frequency of keyword co-occurrence, the higher the research intensity of its literature. Service and value are the most commonly used keywords, followed by capacity. Additionally, the more common words are conservation, ecological value, benefit, effect, and factor et al., which indicates that research on the conservation of ecosystems based on the results of ecological asset accounting and the factors affecting ecological carrying capacity have attracted much attention.

Figure 4. Keywords clustering mapping: Different colors in the map represent three clusters. The larger nodes in the map represent more occurrences, indicating a greater degree of contribution in the related field. Closely connected nodes are connected by lines, and the greater the link strength, the stronger the relationship that exists.

Figure 5. The density visualization of keywords: The figure shows a density map according to the frequency of keywords. Some keywords with high frequency are shown in the figure. The higher the frequency of a keyword, the larger its label, and its density will be more apparent (the color turns brighter).