Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Roshana Thambyrajah | + 3353 word(s) | 3353 | 2022-01-25 07:51:51 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | -12 word(s) | 3341 | 2022-01-30 06:52:03 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Thambyrajah, R. Notch Signaling in HSC Emergence. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19016 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Thambyrajah R. Notch Signaling in HSC Emergence. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19016. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Thambyrajah, Roshana. "Notch Signaling in HSC Emergence" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19016 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Thambyrajah, R. (2022, January 29). Notch Signaling in HSC Emergence. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/19016

Thambyrajah, Roshana. "Notch Signaling in HSC Emergence." Encyclopedia. Web. 29 January, 2022.

Copy Citation

The Notch signaling pathway controls cell fate decisions during embryonic development and is highly conserved in metazoan.

Notch signaling

HSC

developmental hematopoiesis

AGM

1. Introduction to HSC Development

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) sustain the adult blood system by generating mature blood cells of all lineages through multi-potent progenitors of intermediate stages [1]. During embryogenesis, the hematopoietic system is established through several waves starting from Embryonic day (E) 7.5. In mouse, the earliest blood cells are produced in the blood islands of the yolk sac (extra embryonic) which continue to distribute hematopoietic cells with erythro-myeloid lineage potential by E8.5 and multipotent hematopoietic cells also with lymphoid lineage potential at later stages [2][3][4]. Cells originating from the early waves of hematopoiesis also include tissue resident macrophages that infiltrate various organs and fulfil tissue-specific and niche-specific functions, including functions during HSC development [5][6]. However, the first HSCs with hematopoietic reconstitution capacity are detected from E10.5 onwards within the embryo (intra-embryonically). They are particularly enriched in the trunk of the embryo where the aorta, gonads and the mesonephros meet (AGM). The hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPC) accumulate as Intra-aortic hematopoietic clusters (IAHC) in the dorsal aorta (DA) [7][8][9][10][11]. Although nascent HSCs have been associated to other sites (umbilical cord, placenta, head [12][13][14][15]), blood emergence is closely associated with a specialized endothelial cell population, termed hemogenic endothelium (HE), that trans differentiate to blood by losing their endothelial identity and gaining hematopoietic potential. Over the years, several studies have conclusively demonstrated this endothelial-to-hematopoietic transition (EHT) by in vivo imaging of different animal models, as well as in vitro differentiation to blood from Embryonic Stem (ES) cells [16][17][18][19][20][21][22]. HE cells can be identified by the co-expression of endothelial marker gene expression such as CD31, CDH5, ACE and CD44 and key hematopoietic transcription factors, including Runx1, Gfi1 and Gata2 [23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30]. The earliest transcription factors detected in the HE, Runx1 and Gata2, are downstream of Notch signaling, [31][32] and later the expression of Gfi1 is detected in a discrete subset of Runx1 positive cells that are restricted to the HE and IAHC, while runx1 expression extends to the subaortic mesenchyme [30]. Several other surface markers and transcription factors have been described to enrich HSC activity, including Sca1, Gpr56, CD27 and CD201 (PROCR) [33] [34][35][36][37]. Once the EHT process is completed, the cells proliferate and recruit other cells [29][38] forming IAHC that appear associated to the ventral wall of the dorsal aorta starting between the embryonic days E10.25–E12 in the mouse (week 4–5 in human embryo). Although HE and IAHC can be observed on both the ventral and the dorsal side of the aorta within this time window, only the IAHC associated with the ventral side contain transplantable HSCs [27][39]. This has been mainly attributed to pathways, including BMP, hedgehog and Notch signaling that are polarized to the ventral domain [39]. The emerging HSPCs then migrate to the fetal liver for maturation and expansion [40]. The sites of HSC emergence and their migration between hematopoietic niches are very well conserved in vertebrates [41]. In addition, in the zebrafish, HSPCs emerge from the dorsal aorta of the trunk. However, unlike in the mouse model, the early erythroid-myeloid progenitors and the emergence of progenitors with HSC properties occur within a shared spatial and temporal manner [42]. At least in the mouse, transplantation assays performed at different time points of HSPC emergence, early (pre)-HSC can readily contribute to the blood system of neonates, but not directly to the adult system [43]. This potency is only evident in HSCs that are older than E11.5. Even then, only a very small fraction of these HSPCs are functional HSCs [25][26][27][44], with the majority being blood progenitors. Therefore, although there is consensus regarding the site of HSC emergence. It is unclear whether HPCs and HSC share the same HE precursors, or if in fact, the HE is a heterogeneous cell population with different capacities. Moreover, further clarity is required in understanding which molecular pathways are unique to HSC emergence or shared with HPCs. Adding further to the complexity, EHT and HSPC emergence occurs at a developmental stage when angiogenesis is in progress and vascular identity (arterial versus venous) is being established. Therefore, it is highly plausible that both these processes share common signaling pathways to some extent.

2. The Basics of Notch Signaling

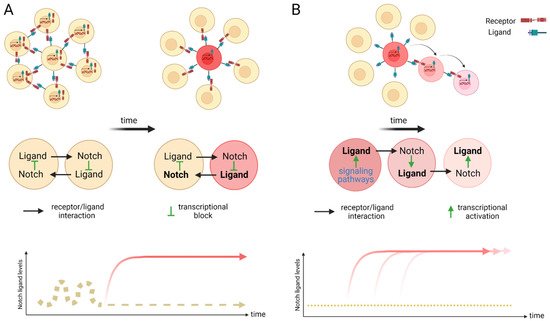

The Notch signaling pathway controls cell fate decisions during embryonic development and is highly conserved in metazoan [45]. In the classical model, Notch signaling is established through cell–cell contact. Adjacent cells express the Notch receptor and/or ligand on their cell surface. Upon interaction, the receptor is activated and results in the nuclear translocation of the active form of the Notch signaling molecule (Figure 1). In mammals, there are four Notch receptors (Notch1–4) and five ligands: there are three Delta ligands (Dll1, Dll3 and Dll4) and two Jagged ligands (Jag1 and Jag2), but in zebrafish some of these receptors and ligands have undergone duplications and therefore have two isoforms [42]. Typically, upon ligand binding (Delta or Jagged), the Notch receptor undergoes three protease cleavages thereby releasing the Notch Intracellular Domain (NICD), which then translocates into the nucleus. In the nucleus, the NICD forms a complex with its coregulator, RBPJ (Recombination signal-Binding Protein for Ig Kappa J region) and recruits co-activators such as MAML (Mastermind-Like) to its gene targets. The best characterized NICD–RBPJ complex targets are the transcriptional repressors genes of the Hes/Her family in vertebrates (Figure 1) [46]. These Hes/Her transcription factors can repress genes driving cell specification, cell differentiation and cell cycle arrest [46]. Hes/Her can also form a negative feedback loop and repress Notch ligand expression in a particular cell. This first receiver can now send out a signal and inhibit the neighboring cell through the remaining ligands on its cell surface (Figure 2). This lateral inhibition mechanism results in one cell that is unique in a homogenous cell population. This cell can be destined to acquire a distinctive fate, by inducing Notch activation and repressing this specific fate in the neighboring cells (Figure 2) [47][48][49]. However, the reverse mechanism can be used to specify a small group of cells with the identical fate. Here, an adjacent cell expresses the Notch ligand upon Notch activation which then further spreads this (positive) feedback loop (lateral induction) to the next neighboring cell [50][51]. Subsequently, both the interacting cells and a small group of cells within a population acquire the same fate (Figure 2). On the contrary, Notch receptors and ligands can also form cis interactions that inhibit or activate Notch signaling. In these instances, the receptor and the ligand are present on the surface of the same cell, form a complex and thereby mask this cell from further Notch activity [52][53][54]. In vertebrates, different combinations of Notch receptor and ligand can be expressed in a cell population and their spatiotemporal abundance contributes further to the complexity of Notch signaling. Interactions of different ligands with the same receptor can also trigger distinct responses. For example, during angiogenesis, JAG1 and DLL4 drive different outcomes in the control of cell fate decisions. Similarly, Dll1 and Dll4 induce different Notch activation dynamics resulting in opposing gene programs and cell fates [55]. Finally, Fringe glycotransferases (Radical, Lunatic and Manic) can modify the Notch receptor and alter the affinity between Notch receptors and their ligands and further fine tune the cellular Notch activity [56].

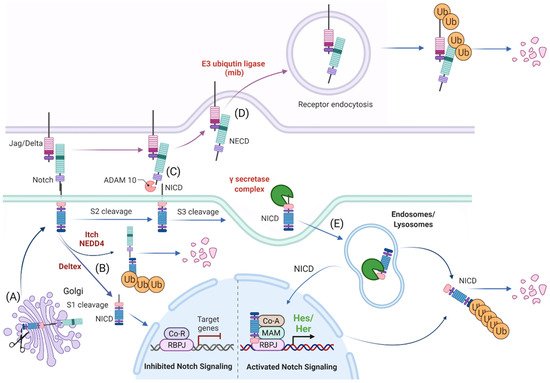

Figure 1. Schematic representation of Notch signaling molecule interaction, their localization within the cellular compartment and their life cycle. (A) Notch receptors undergo S1 cleavage in the Golgi vesicle. (B) Notch receptors can be directly degraded (without ligand interaction) via NEDD4/ITCH from the cellular surface or processed to Notch Intracellular Domain (NICD) in the absence of a Notch ligand by Deltex. (C) In the canonical Notch receptor processing, Notch receptor is cleaved upon contact with a ligand by ADAM family members at the c-terminal (intracellular) end that leads to exposure of the S3 cleavage site. (D) The ligand sending cell endocytoses the extracellular domain of the Notch receptor (NECD) that it “pulled off” when interacting with the receptor. (E) The NICD is then further processed by the γ-secretase complex to an activated NICD (cleavage at Val1744) within endosomes/lysosomes that can either be targeted for degradation or translocate to the nucleus for target gene modulation. Ub: ubiquitination, Co-R: undefined co-repressor, Co-A: undefined co-activator, MAM: MAML. Created with BioRender.com (accessed on 15 January 2022).

Figure 2. Scheme of lateral inhibition (A) and lateral induction (B). (A) Within an equipotent cell population with fluctuating Notch activity, a stochastic up-regulation of Notch activation can induce the expression of the Notch downstream transcriptional repressors that in turn silence the expression of ligand transcription. The remaining receptors on the surface of this cell can now act as signal senders for neighboring cells and induce a different fate to its own. Over time, a salt and pepper pattern emerges. A cell with high levels of ligand (sender) is positioned surrounded by receptor expressing cells (receivers). This mechanism of cell fate determination is termed lateral inhibition. (B) Lateral induction is the term used for sequential induction of Notch activity within adjacent cells. In this scenario, Notch activity induces further transcriptional activation of Notch receptors and ligands. The cell stays activated (through the newly synthesized receptor) but further activates the adjacent through the ligand. This cycle is repeated over time to establish a group of cells with the identical cell fate. Arrow depicts direction of activation. Created with BioRender.com (accessed on 15 January 2022).

3. Processing of the Notch Receptors and Ligands

3.1. Release of the Transcriptionally Active NICD

The Notch receptor is cleaved at multiple sites and stages before its NICD is released into the nucleus. Initially, the Notch receptor is post-translationally cleaved at the S1 site whilst in the trans-Golgi network by a Furin-like protease, which results in a heterodimer that is held together by Ca2+-dependent ionic bonds and can be integrated into the cell membrane. Here, it is important to note, that this first cleavage exposes the negative regulatory region (NRR) at the base of the extracellular domain (ECD) and this is critical in preventing Notch activation in the absence of the correct signals. When a receptor–ligand interaction occurs, conformational changes in the NRR allow access to the ADAM proteins to the S2 cleavage site that is also based in the ECD of the Notch receptor [57][58][59]. Once the S2 cleavage occurs, further conformational changes expose the S3 cleavage site on the intracellular domain of the receptor to the γ-secretase complex that is comprised of multiple protein subunits including Nicastrin, Anterior pharynx defective-1, Presenilin enhancer-2 and the catalytically active subunit PRESENILIN. This complex is present at the plasma membrane and localizes to early/late endosomes and in lysosomes. Notch receptor and γ-secretase co-localization to the endocytic compartment is critical to Notch activation. During endocytosis, CATHRIN is recruited to the plasma membrane and adheres to lipid- or protein-binding domains at the membrane with the help of adaptor proteins. These adaptors help to form a curved vesicle called CLATHRIN-coated pits. These pits invaginate with the help of bending-proteins, such as EPSIN and form vesicles that eventually bud off from the membrane. The vesicle is then uncoated and can then fuse with other intracellular structures such as endosomes and lysosomes [60][61]. The S3 cleavage occurs within these intracellular vesicles and releases the NICD and allows Notch signaling to be initiated.

3.2. The Role of Notch Ligand in Activating Notch Signaling

Notch activation is not only dependent on receptor-ligand interactions, but also on the ECD dissociation from the receptor and its trans-endocytosis into the ligand-expressing cell [62][63]. It has been suggested that this pulling force is necessary for conformational changes in the NRR region and for S2 cleavage by ADAM family members, ADAM10 and ADAM17/TACE, after which the ECD is free to be trans-endocytosed [63].

3.3. Notch Ligand Independent NICD Activation

As an alternative, Notch endocytosis has been suggested not only as necessary for its activation, but also in order to decrease the level of Notch signal by reducing its expression on the cell surface. Notch can indeed be marked for degradation via ubiquitination by E3-ligases such as AIP4/ITCH [64] or Nedd4 [65][66]. It is then endocytosed via NUMB which recruits the AP2-clathrin adaptor-complex [67][68]. Finally, Notch activity can also occur independent of ligand interaction. DELTEX, a E3 ubiquitin ligase, can facilitate the processing of the Notch receptor in the endosomes and thereby release the NICD in the absence of a ligand [69][70].

In conclusion, complete processing of Notch requires multiple cleavages, classically through interaction with a ligand and internalization of the receptor, where it then becomes cleaved and fully activated in the endosome. Each of these steps requires the participation of several proteins and they all together fine tune the final NICD activity.

4. Notch Activity during Zebrafish Angiogenesis

Fate-mapping studies in zebrafish of mesodermal progenitors labeled at midblastula or gastrula stages indicate that at least some of the putative hemangioblast are bipotential and capable of giving rise to cells of both lineages, although the majority of labeled cells give rise to only one lineage [71][72][73]. Nevertheless, the early angioblasts assemble via migration to the midline of the trunk into two axial vessels: the dorsal aorta and the posterior cardinal vein (PCV), found just below the DA. Interestingly, fate-mapping studies in the zebrafish indicate that angioblasts become restricted to either an arterial or venous fate before they start to migrate to the trunk midline to form the DA and PCV [74]. Hedgehog (Hh) is a morphogen known to regulate epithelial/mesenchymal interactions during embryonic development and sits at the apex of the signaling cascade that leads to arterial and venous identity [74][75]. In zebrafish, its secreted from the endoderm during gastrulation and later from the notochord and forms a decreasing gradient to induce the expression of two families of angiogenic cytokines, vascular endothelial growth factor-1 (vegf) from the somites and angiopoietins-1 and -2 (Ang1/Ang2) [76]. Vegf-A is produced by multiple cell types, including somites and smooth muscle cells and regulates differentiation, proliferation and survival of ECs [77][78]. In angioblasts that have arterial identity, Vegf interacts with the Vegf receptor Flk1/Vegfr2 and Np1 complex to induce the activation of the Notch and Erk signaling pathways [79][80]. In contrast, in venous angioblasts, chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor II (Coup-TFII) acts to suppress the Notch and Erk pathways and thereby repress arterial fate induction [74][80]. The Notch pathway activation is required for imperative for arterial specification and arterial marker expression, including Ephrinb2, Notch1, Notch4, Dll4 and the Notch downstream target gene Hey2 (a hairy/enhancer-of-split-related basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor) [81]. The venous angioblast express COUP-TFII and the B4 ephrin receptor (EphB4) [80][82].

5. Notch Activity Contribution to Zebrafish HSPC Emergence from the Dorsal Aorta

Analysis of the mind bomb mutant in zebrafish embryos has demonstrated the requirement of Notch signaling in HSPC emergence from the dorsal aorta. Mind bomb is an E3 ubiquitin ligase, which is essential for endocytosis of Notch ligands upon Notch receptor and ligand interaction [83]. The mutants display a complete absence of transcripts for the HSC marker genes cmyb and runx1 in the ventral floor of the dorsal aorta at 36 h post fertilization (hpf), although the erythro-myeloid progenitor (EMP) generation is unaffected [32][84]. Accordingly, overexpression of the Notch intracellular domain resulted in an expansion of cmyb and runx1 at 36 hpf that reaches into the venous endothelium, but notably, without increasing efnB2a expression into the vein [32]. Studies have also addressed the requirement for Notch signaling in HSPC emergence by generating morphants for Notch receptors and ligands. The two zebrafish Notch ligands dlc and dld are expressed from the somitic tissue around 17.5 hpf, just after the axial vessels are beginning to segregate. Both ligands are dependent on Wnt16 expression from the somites and critical for proper blood emergence [85]. Enforced expression of Nicd at 14 hpf could rescue cmyb expression at 36 hpf in these morphants. However, later induction failed to induce cmyb expression along the dorsal aorta [85]. The authors reason that the critical phase WNT16 (WNT family member 16) mediated Notch signaling required for HSC specification occurs between 15–17 hpf and not thereafter. A later study from the same group identified the adhesion molecules Jam1a and Jam2a as the critical contributors to this dlc and dld ligand function. jam1a and jam2a are expressed on early vascular progenitors and are activated through Notch by the dlc and dld ligand presenting somites [86]. When this interaction is missing, arterial specification is unaffected, but HE is lost [86]. In order to identify if any of the Notch signaling molecules were affected by Jam1a loss, they sampled all the aortic Notch receptor and ligand genes (notch1a, notch1b, notch3, dlc and dll4), but detected no changes. In yet a different study, the same group discovered notch3 receptor expression in the somites and on the vascular progenitors at early time points. By using morpholino mediated knock down approaches, they show that Notch3 is molecularly situated downstream of dlc and dld [87] that is important for HE specification, but dispensable for arterial fate determination. Only a second wave of Notch activity which is driven by the aortic expression of Notch1a and Notch1b is crucial for both arterial identity and most importantly, HSPC formation [87]. Which Notch receptors the zebrafish Dlc and Dld interact with and which downstream targets they mediate is currently, not known. At least within the dorsal aorta, where the two Notch isoforms notch1a and notch1b are expressed, the ligand Jag1a seem to play a dominant role in HSPC emergence, as in the mouse. Morphants for Jag1a display an established arterial fate but have compromised HE and HSPC formation ([88]. Finally, time lapse imaging on a Notch responsive transgenic zebrafish line illustrates Notch activity in HE and cells undergoing EHT which decreases as they leave the DA [89].

Altogether, Notch activity is pivotal for HSPC emergence from the DA of the zebrafish model. Two waves of Notch activity seem required. At least in the zebrafish model, firstly, Notch3 from the somites interacts with the ligands Dlc and Dld in the vascular progenitors. Epistatic analyses demonstrate that Notch3 function lies downstream of Wnt16, which is required for HSC specification through its regulation of two Notch ligands, dlc and dld [87]. Once the vascular progenitors segregate according to their arterial/venous fate, Notch activation in aortic cells through Notch1a/Notch1b and Jag1a is essential. Together, they provide the indispensable Notch activity levels for HE specification and HSPC emergence.

Downstream Targets of Notch Activation in Zebrafish HSPC

Genome duplication within the teleost lineage has given rise two Gata2 paralogs in zebrafish, gata2a and gata2b. Gene expression analysis demonstrates a distinct pattern of gata2a and gata2b expression in zebrafish [90]. Gata2a is expressed throughout the endothelium, but Gata2b is restricted to the HE subpopulation of the DA. Expression of Gata2b begins in the vascular cord during posterior lateral mesoderm migration and is initiated in a subpopulation of fli1a+ (early vascular progenitors) cells [90]. This study on genetic morphants demonstrates that Notch1a and Notch1b are required for gata2b expression in the aorta, but not gata2a. Furthermore, gata2b morphants lose runx1/cmyb expression in the trunk, but not the expression of EfnB2a [90] with the study further highlighting how two isoforms can be employed to direct different cell fates. Finally, another direct Notch target, Hey2 is demonstrated to act upstream of Notch activation in the dorsal aorta in a zebrafish model [81]. Hey2 expression is first detected in the early angioblast when the formation of the axial vessels and independent of Notch signaling, as the hey2 expression persists in Rbpj morphants and mind bomb mutants [81]. Intriguingly, Hey2 morphants do not express the receptor notch1b or notch5 in the dorsal aorta that are important for Notch signaling in arterial cells, but the Notch ligand dll4 is readily detected, suggesting that initiation of dll4 expression is not dependent on Notch activation through notch1b (or notch5). Consequently, the arterial gene efnb2a is not expressed (due to lack of Notch1b), flt4 is not downregulated (venous gene that is usually silenced by Notch activity) and runx1+ hematopoietic cells do not emerge from the DA angioblast cord. However, the lack of hematopoietic progenitors can be rescued by enforced expression of NICD in Hey2 morphants, suggesting that Hey2 indeed acts upstream of Notch activity induced by Notch1b in the aorta [81]. In summary, in zebrafish, the Notch target hey2 seems to mark the arterial and HE primed endothelial cells from an early precursor stage already. During the dorsal aorta segregation from the venous endothelium, Notch activity is resumed for arterial identity and hematopoietic commitment. Here, Notch signaling mainly fine tunes the expression and cross regulation of the transcription factors gata2.

References

- Challen, G.A.; Boles, N.; Lin, K.K.; Goodell, M.A. Mouse hematopoietic stem cell identification and analysis. Cytom. A 2009, 75, 14–24.

- Frame, J.M.; Fegan, K.H.; Conway, S.J.; McGrath, K.E.; Palis, J. Definitive Hematopoiesis in the Yolk Sac Emerges from Wnt-Responsive Hemogenic Endothelium Independently of Circulation and Arterial Identity. Stem Cells 2016, 34, 431–444.

- Frame, J.M.; McGrath, K.E.; Palis, J. Erythro-myeloid progenitors: “definitive” hematopoiesis in the conceptus prior to the emergence of hematopoietic stem cells. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 2013, 51, 220–225.

- Yamane, T. Mouse Yolk Sac Hematopoiesis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 6, 80.

- Gomez Perdiguero, E.; Klapproth, K.; Schulz, C.; Busch, K.; Azzoni, E.; Crozet, L.; Garner, H.; Trouillet, C.; de Bruijn, M.F.; Geissmann, F.; et al. Tissue-resident macrophages originate from yolk-sac-derived erythro-myeloid progenitors. Nature 2015, 518, 547–551.

- Hoeffel, G.; Ginhoux, F. Ontogeny of Tissue-Resident Macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 486.

- Cumano, A.; Ferraz, J.C.; Klaine, M.; Di Santo, J.P.; Godin, I. Intraembryonic, but not yolk sac hematopoietic precursors, isolated before circulation, provide long-term multilineage reconstitution. Immunity 2001, 15, 477–485.

- de Bruijn, M.F.; Speck, N.A.; Peeters, M.C.; Dzierzak, E. Definitive hematopoietic stem cells first develop within the major arterial regions of the mouse embryo. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 2465–2474.

- Jaffredo, T.; Gautier, R.; Eichmann, A.; Dieterlen-Lievre, F. Intraaortic hemopoietic cells are derived from endothelial cells during ontogeny. Development 1998, 125, 4575–4583.

- Medvinsky, A.; Dzierzak, E. Definitive hematopoiesis is autonomously initiated by the AGM region. Cell 1996, 86, 897–906.

- North, T.E.; de Bruijn, M.F.; Stacy, T.; Talebian, L.; Lind, E.; Robin, C.; Binder, M.; Dzierzak, E.; Speck, N.A. Runx1 expression marks long-term repopulating hematopoietic stem cells in the midgestation mouse embryo. Immunity 2002, 16, 661–672.

- Gekas, C.; Dieterlen-Lievre, F.; Orkin, S.H.; Mikkola, H.K. The placenta is a niche for hematopoietic stem cells. Dev. Cell 2005, 8, 365–375.

- Hordyjewska, A.; Popiolek, L.; Horecka, A. Characteristics of hematopoietic stem cells of umbilical cord blood. Cytotechnology 2015, 67, 387–396.

- Li, Z.; Lan, Y.; He, W.; Chen, D.; Wang, J.; Zhou, F.; Wang, Y.; Sun, H.; Chen, X.; Xu, C.; et al. Mouse embryonic head as a site for hematopoietic stem cell development. Cell Stem Cell 2012, 11, 663–675.

- Mikkola, H.K.; Gekas, C.; Orkin, S.H.; Dieterlen-Lievre, F. Placenta as a site for hematopoietic stem cell development. Exp. Hematol. 2005, 33, 1048–1054.

- Kissa, K.; Herbomel, P. Blood stem cells emerge from aortic endothelium by a novel type of cell transition. Nature 2010, 464, 112–115.

- Bertrand, J.Y.; Chi, N.C.; Santoso, B.; Teng, S.; Stainier, D.Y.; Traver, D. Haematopoietic stem cells derive directly from aortic endothelium during development. Nature 2010, 464, 108–111.

- Boisset, J.C.; van Cappellen, W.; Andrieu-Soler, C.; Galjart, N.; Dzierzak, E.; Robin, C. In vivo imaging of haematopoietic cells emerging from the mouse aortic endothelium. Nature 2010, 464, 116–120.

- Zovein, A.C.; Hofmann, J.J.; Lynch, M.; French, W.J.; Turlo, K.A.; Yang, Y.; Becker, M.S.; Zanetta, L.; Dejana, E.; Gasson, J.C.; et al. Fate tracing reveals the endothelial origin of hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2008, 3, 625–636.

- Lam, E.Y.; Hall, C.J.; Crosier, P.S.; Crosier, K.E.; Flores, M.V. Live imaging of Runx1 expression in the dorsal aorta tracks the emergence of blood progenitors from endothelial cells. Blood 2010, 116, 909–914.

- Dzierzak, E.; Bigas, A. Blood Development: Hematopoietic Stem Cell Dependence and Independence. Cell Stem Cell 2018, 22, 639–651.

- Lancrin, C.; Sroczynska, P.; Serrano, A.G.; Gandillet, A.; Ferreras, C.; Kouskoff, V.; Lacaud, G. Blood cell generation from the hemangioblast. J. Mol. Med. 2010, 88, 167–172.

- Tsai, F.Y.; Keller, G.; Kuo, F.C.; Weiss, M.; Chen, J.; Rosenblatt, M.; Alt, F.W.; Orkin, S.H. An early haematopoietic defect in mice lacking the transcription factor GATA-2. Nature 1994, 371, 221–226.

- Minegishi, N.; Ohta, J.; Yamagiwa, H.; Suzuki, N.; Kawauchi, S.; Zhou, Y.; Takahashi, S.; Hayashi, N.; Engel, J.D.; Yamamoto, M. The mouse GATA-2 gene is expressed in the para-aortic splanchnopleura and aorta-gonads and mesonephros region. Blood 1999, 93, 4196–4207.

- Rybtsov, S.; Sobiesiak, M.; Taoudi, S.; Souilhol, C.; Senserrich, J.; Liakhovitskaia, A.; Ivanovs, A.; Frampton, J.; Zhao, S.; Medvinsky, A. Hierarchical organization and early hematopoietic specification of the developing HSC lineage in the AGM region. J. Exp. Med. 2011, 208, 1305–1315.

- Taoudi, S.; Gonneau, C.; Moore, K.; Sheridan, J.M.; Blackburn, C.C.; Taylor, E.; Medvinsky, A. Extensive hematopoietic stem cell generation in the AGM region via maturation of VE-cadherin+CD45+ pre-definitive HSCs. Cell Stem Cell 2008, 3, 99–108.

- Taoudi, S.; Medvinsky, A. Functional identification of the hematopoietic stem cell niche in the ventral domain of the embryonic dorsal aorta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 9399–9403.

- Gao, X.; Johnson, K.D.; Chang, Y.I.; Boyer, M.E.; Dewey, C.N.; Zhang, J.; Bresnick, E.H. Gata2 cis-element is required for hematopoietic stem cell generation in the mammalian embryo. J. Exp. Med. 2013, 210, 2833–2842.

- Fadlullah, M.Z.; Neo, W.H.; Lie, A.L.M.; Thambyrajah, R.; Patel, R.; Mevel, R.; Aksoy, I.; Do Khoa, N.; Savatier, P.; Fontenille, L.; et al. Murine AGM single-cell profiling identifies a continuum of hemogenic endothelium differentiation marked by ACE. Blood 2021, 139, 343–356.

- Thambyrajah, R.; Mazan, M.; Patel, R.; Moignard, V.; Stefanska, M.; Marinopoulou, E.; Li, Y.; Lancrin, C.; Clapes, T.; Moroy, T.; et al. GFI1 proteins orchestrate the emergence of haematopoietic stem cells through recruitment of LSD1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016, 18, 21–32.

- Robert-Moreno, A.; Espinosa, L.; de la Pompa, J.L.; Bigas, A. RBPjkappa-dependent Notch function regulates Gata2 and is essential for the formation of intra-embryonic hematopoietic cells. Development 2005, 132, 1117–1126.

- Burns, C.E.; Traver, D.; Mayhall, E.; Shepard, J.L.; Zon, L.I. Hematopoietic stem cell fate is established by the Notch-Runx pathway. Genes Dev. 2005, 19, 2331–2342.

- Zhou, F.; Li, X.; Wang, W.; Zhu, P.; Zhou, J.; He, W.; Ding, M.; Xiong, F.; Zheng, X.; Li, Z.; et al. Tracing haematopoietic stem cell formation at single-cell resolution. Nature 2016, 533, 487–492.

- Maglitto, A.; Mariani, S.A.; de Pater, E.; Rodriguez-Seoane, C.; Vink, C.S.; Piao, X.; Lukke, M.L.; Dzierzak, E. Unexpected redundancy of Gpr56 and Gpr97 during hematopoietic cell development and differentiation. Blood Adv. 2021, 5, 829–842.

- Solaimani Kartalaei, P.; Yamada-Inagawa, T.; Vink, C.S.; de Pater, E.; van der Linden, R.; Marks-Bluth, J.; van der Sloot, A.; van den Hout, M.; Yokomizo, T.; van Schaick-Solerno, M.L.; et al. Whole-transcriptome analysis of endothelial to hematopoietic stem cell transition reveals a requirement for Gpr56 in HSC generation. J. Exp. Med. 2015, 212, 93–106.

- de Bruijn, M.F.; Ma, X.; Robin, C.; Ottersbach, K.; Sanchez, M.J.; Dzierzak, E. Hematopoietic stem cells localize to the endothelial cell layer in the midgestation mouse aorta. Immunity 2002, 16, 673–683.

- Vink, C.S.; Calero-Nieto, F.J.; Wang, X.; Maglitto, A.; Mariani, S.A.; Jawaid, W.; Gottgens, B.; Dzierzak, E. Iterative Single-Cell Analyses Define the Transcriptome of the First Functional Hematopoietic Stem Cells. Cell Rep. 2020, 31, 107627.

- Porcheri, C.; Golan, O.; Calero-Nieto, F.J.; Thambyrajah, R.; Ruiz-Herguido, C.; Wang, X.; Catto, F.; Guillen, Y.; Sinha, R.; Gonzalez, J.; et al. Notch ligand Dll4 impairs cell recruitment to aortic clusters and limits blood stem cell generation. EMBO J. 2020, 39, e104270.

- McGarvey, A.C.; Rybtsov, S.; Souilhol, C.; Tamagno, S.; Rice, R.; Hills, D.; Godwin, D.; Rice, D.; Tomlinson, S.R.; Medvinsky, A. A molecular roadmap of the AGM region reveals BMPER as a novel regulator of HSC maturation. J. Exp. Med. 2017, 214, 3731–3751.

- Mahony, C.B.; Bertrand, J.Y. How HSCs Colonize and Expand in the Fetal Niche of the Vertebrate Embryo: An Evolutionary Perspective. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 34.

- Ciau-Uitz, A.; Monteiro, R.; Kirmizitas, A.; Patient, R. Developmental hematopoiesis: Ontogeny, genetic programming and conservation. Exp. Hematol. 2014, 42, 669–683.

- Gering, M.; Patient, R. Notch signalling and haematopoietic stem cell formation during embryogenesis. J. Cell Physiol. 2010, 222, 11–16.

- Boisset, J.C.; Clapes, T.; Klaus, A.; Papazian, N.; Onderwater, J.; Mommaas-Kienhuis, M.; Cupedo, T.; Robin, C. Progressive maturation toward hematopoietic stem cells in the mouse embryo aorta. Blood 2015, 125, 465–469.

- Medvinsky, A.; Rybtsov, S.; Taoudi, S. Embryonic origin of the adult hematopoietic system: Advances and questions. Development 2011, 138, 1017–1031.

- Artavanis-Tsakonas, S.; Rand, M.D.; Lake, R.J. Notch signaling: Cell fate control and signal integration in development. Science 1999, 284, 770–776.

- Kageyama, R.; Ohtsuka, T.; Kobayashi, T. The Hes gene family: Repressors and oscillators that orchestrate embryogenesis. Development 2007, 134, 1243–1251.

- Henrique, D.; Schweisguth, F. Mechanisms of Notch signaling: A simple logic deployed in time and space. Development 2019, 146, dev172148.

- Benedito, R.; Roca, C.; Sorensen, I.; Adams, S.; Gossler, A.; Fruttiger, M.; Adams, R.H. The notch ligands Dll4 and Jagged1 have opposing effects on angiogenesis. Cell 2009, 137, 1124–1135.

- Petrovic, J.; Formosa-Jordan, P.; Luna-Escalante, J.C.; Abello, G.; Ibanes, M.; Neves, J.; Giraldez, F. Ligand-dependent Notch signaling strength orchestrates lateral induction and lateral inhibition in the developing inner ear. Development 2014, 141, 2313–2324.

- de Celis, J.F.; Bray, S. Feed-back mechanisms affecting Notch activation at the dorsoventral boundary in the Drosophila wing. Development 1997, 124, 3241–3251.

- Hartman, B.H.; Reh, T.A.; Bermingham-McDonogh, O. Notch signaling specifies prosensory domains via lateral induction in the developing mammalian inner ear. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 15792–15797.

- del Alamo, D.; Rouault, H.; Schweisguth, F. Mechanism and significance of cis-inhibition in Notch signalling. Curr. Biol. 2011, 21, R40–R47.

- Sprinzak, D.; Lakhanpal, A.; LeBon, L.; Garcia-Ojalvo, J.; Elowitz, M.B. Mutual inactivation of Notch receptors and ligands facilitates developmental patterning. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2011, 7, e1002069.

- Sprinzak, D.; Lakhanpal, A.; Lebon, L.; Santat, L.A.; Fontes, M.E.; Anderson, G.A.; Garcia-Ojalvo, J.; Elowitz, M.B. Cis-interactions between Notch and Delta generate mutually exclusive signalling states. Nature 2010, 465, 86–90.

- Nandagopal, N.; Santat, L.A.; LeBon, L.; Sprinzak, D.; Bronner, M.E.; Elowitz, M.B. Dynamic Ligand Discrimination in the Notch Signaling Pathway. Cell 2018, 172, 869–880 e819.

- Urata, Y.; Takeuchi, H. Effects of Notch glycosylation on health and diseases. Dev. Growth Differ. 2020, 62, 35–48.

- Gordon, W.R.; Vardar-Ulu, D.; Histen, G.; Sanchez-Irizarry, C.; Aster, J.C.; Blacklow, S.C. Structural basis for autoinhibition of Notch. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007, 14, 295–300.

- Tiyanont, K.; Wales, T.E.; Aste-Amezaga, M.; Aster, J.C.; Engen, J.R.; Blacklow, S.C. Evidence for increased exposure of the Notch1 metalloprotease cleavage site upon conversion to an activated conformation. Structure 2011, 19, 546–554.

- Weng, A.P.; Ferrando, A.A.; Lee, W.; Morris, J.P.t.; Silverman, L.B.; Sanchez-Irizarry, C.; Blacklow, S.C.; Look, A.T.; Aster, J.C. Activating mutations of NOTCH1 in human T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science 2004, 306, 269–271.

- Mumm, J.S.; Schroeter, E.H.; Saxena, M.T.; Griesemer, A.; Tian, X.; Pan, D.J.; Ray, W.J.; Kopan, R. A ligand-induced extracellular cleavage regulates gamma-secretase-like proteolytic activation of Notch1. Mol. Cell 2000, 5, 197–206.

- Struhl, G.; Adachi, A. Requirements for presenilin-dependent cleavage of notch and other transmembrane proteins. Mol. Cell 2000, 6, 625–636.

- Parks, A.L.; Klueg, K.M.; Stout, J.R.; Muskavitch, M.A. Ligand endocytosis drives receptor dissociation and activation in the Notch pathway. Development 2000, 127, 1373–1385.

- Hansson, E.M.; Lanner, F.; Das, D.; Mutvei, A.; Marklund, U.; Ericson, J.; Farnebo, F.; Stumm, G.; Stenmark, H.; Andersson, E.R.; et al. Control of Notch-ligand endocytosis by ligand-receptor interaction. J. Cell Sci. 2010, 123, 2931–2942.

- Chastagner, P.; Israel, A.; Brou, C. AIP4/Itch re.egulates Notch receptor degradation in the absence of ligand. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2735.

- Sakata, T.; Sakaguchi, H.; Tsuda, L.; Higashitani, A.; Aigaki, T.; Matsuno, K.; Hayashi, S. Drosophila Nedd4 regulates endocytosis of notch and suppresses its ligand-independent activation. Curr. Biol. 2004, 14, 2228–2236.

- Wilkin, M.B.; Carbery, A.M.; Fostier, M.; Aslam, H.; Mazaleyrat, S.L.; Higgs, J.; Myat, A.; Evans, D.A.; Cornell, M.; Baron, M. Regulation of notch endosomal sorting and signaling by Drosophila Nedd4 family proteins. Curr. Biol. 2004, 14, 2237–2244.

- McGill, M.A.; McGlade, C.J. Mammalian numb proteins promote Notch1 receptor ubiquitination and degradation of the Notch1 intracellular domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 23196–23203.

- McGill, M.A.; Dho, S.E.; Weinmaster, G.; McGlade, C.J. Numb regulates post-endocytic trafficking and degradation of Notch1. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 26427–26438.

- Luo, Z.; Mu, L.; Zheng, Y.; Shen, W.; Li, J.; Xu, L.; Zhong, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y. NUMB enhances Notch signaling by repressing ubiquitination of NOTCH1 intracellular domain. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 12, 345–358.

- Jafar-Nejad, H.; Norga, K.; Bellen, H. Numb: “Adapting” notch for endocytosis. Dev. Cell 2002, 3, 155–156.

- Vogeli, K.M.; Jin, S.W.; Martin, G.R.; Stainier, D.Y. A common progenitor for haematopoietic and endothelial lineages in the zebrafish gastrula. Nature 2006, 443, 337–339.

- Lacaud, G.; Kouskoff, V. Hemangioblast, hemogenic endothelium, and primitive versus definitive hematopoiesis. Exp. Hematol. 2017, 49, 19–24.

- Nishikawa, S. Hemangioblast: An in vitro phantom. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Dev. Biol. 2012, 1, 603–608.

- Zhong, T.P.; Childs, S.; Leu, J.P.; Fishman, M.C. Gridlock signalling pathway fashions the first embryonic artery. Nature 2001, 414, 216–220.

- Lawson, N.D.; Vogel, A.M.; Weinstein, B.M. Sonic hedgehog and vascular endothelial growth factor act upstream of the Notch pathway during arterial endothelial differentiation. Dev. Cell 2002, 3, 127–136.

- Gering, M.; Patient, R. Hedgehog signaling is required for adult blood stem cell formation in zebrafish embryos. Dev. Cell 2005, 8, 389–400.

- Fish, J.E.; Wythe, J.D. The molecular regulation of arteriovenous specification and maintenance. Dev. Dyn. 2015, 244, 391–409.

- Bautch, V.L. VEGF-directed blood vessel patterning: From cells to organism. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a006452.

- Hong, C.C.; Peterson, Q.P.; Hong, J.Y.; Peterson, R.T. Artery/vein specification is governed by opposing phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase and MAP kinase/ERK signaling. Curr. Biol. 2006, 16, 1366–1372.

- Lin, F.J.; Tsai, M.J.; Tsai, S.Y. Artery and vein formation: A tug of war between different forces. EMBO Rep. 2007, 8, 920–924.

- Rowlinson, J.M.; Gering, M. Hey2 acts upstream of Notch in hematopoietic stem cell specification in zebrafish embryos. Blood 2010, 116, 2046–2056.

- Swift, M.R. Weinstein, B.M. Arterial-venous specification during development. Circ. Res. 2009, 104, 576–588.

- Yoon, K.J.; Koo, B.K.; Im, S.K.; Jeong, H.W.; Ghim, J.; Kwon, M.C.; Moon, J.S.; Miyata, T.; Kong, Y.Y. Mind bomb 1-expressing intermediate progenitors generate notch signaling to maintain radial glial cells. Neuron 2008, 58, 519–531.

- Bertrand, J.Y.; Cisson, J.L.; Stachura, D.L.; Traver, D. Notch signaling distinguishes 2 waves of definitive hematopoiesis in the zebrafish embryo. Blood 2010, 115, 2777–2783.

- Clements, W.K.; Kim, A.D.; Ong, K.G.; Moore, J.C.; Lawson, N.D.; Traver, D. A somitic Wnt16/Notch pathway specifies haematopoietic stem cells. Nature 2011, 474, 220–224.

- Kobayashi, I.; Kobayashi-Sun, J.; Kim, A.D.; Pouget, C.; Fujita, N.; Suda, T.; Traver, D. Jam1a-Jam2a interactions regulate haematopoietic stem cell fate through Notch signalling. Nature 2014, 512, 319–323.

- Kim, A.D.; Melick, C.H.; Clements, W.K.; Stachura, D.L.; Distel, M.; Panakova, D.; MacRae, C.; Mork, L.A.; Crump, J.G.; Traver, D. Discrete Notch signaling requirements in the specification of hematopoietic stem cells. EMBO J. 2014, 33, 2363–2373.

- Monteiro, R.; Pinheiro, P.; Joseph, N.; Peterkin, T.; Koth, J.; Repapi, E.; Bonkhofer, F.; Kirmizitas, A.; Patient, R. Transforming Growth Factor beta Drives Hemogenic Endothelium Programming and the Transition to Hematopoietic Stem Cells. Dev. Cell 2016, 38, 358–370.

- Thambyrajah, R.; Ucanok, D.; Jalali, M.; Hough, Y.; Wilkinson, R.N.; McMahon, K.; Moore, C.; Gering, M. A gene trap transposon eliminates haematopoietic expression of zebrafish Gfi1aa, but does not interfere with haematopoiesis. Dev. Biol. 2016, 417, 25–39.

- Butko, E.; Distel, M.; Pouget, C.; Weijts, B.; Kobayashi, I.; Ng, K.; Mosimann, C.; Poulain, F.E.; McPherson, A.; Ni, C.W.; et al. Gata2b is a restricted early regulator of hemogenic endothelium in the zebrafish embryo. Development 2015, 142, 1050–1061.

More

Information

Subjects:

Developmental Biology

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

826

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

30 Jan 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No