Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Carmen Rubio Armendáriz | + 2261 word(s) | 2261 | 2022-01-26 04:21:36 | | | |

| 2 | Dean Liu | Meta information modification | 2261 | 2022-01-27 01:50:47 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Rubio Armendáriz, C. Microplastics as Emerging Food Contaminants. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18871 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Rubio Armendáriz C. Microplastics as Emerging Food Contaminants. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18871. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Rubio Armendáriz, Carmen. "Microplastics as Emerging Food Contaminants" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18871 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Rubio Armendáriz, C. (2022, January 27). Microplastics as Emerging Food Contaminants. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18871

Rubio Armendáriz, Carmen. "Microplastics as Emerging Food Contaminants." Encyclopedia. Web. 27 January, 2022.

Copy Citation

Microplastics (MPs) have been identified as emerging environmental pollutants classified as primary or secondary based on their source.

microplastics

dietary MPs

hazard identification

hazard characterization

1. Introduction

Microplastics (MPs) have been identified as emerging environmental pollutants specially affecting the marine ecosystem, but they should also be considered as a growing food contaminant. Between five and thirteen tons of plastic (1.5–4% of the total global production) reach the marine ecosystems every year [1]. Furthermore, MPs also pose a growing risk for terrestrial ecosystems, as MPs have also been detected in farming soils [2]. Recently, the prevention measures against the spread of the COVID-19 virus have been contributing to an increase of the plastic waste’s accumulation, as protective clothing, accessories, masks, and additional plastic containers and bags are single use [3][4][5].

2. Hazard Identification

Hazard identification is the first step in risk assessment and involves the identification of those biological, chemical, and physical agents capable of causing adverse health effects [6]. MPs are considered emerging food hazards that pose growing challenges and opportunities for researchers. Many studies have identified the presence of MPs in food and beverages, but the current available data could be considered not only insufficient but also of questionable quality. Even though Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) is the most widely used detection method, the absence of consensus about unified nomenclature and a standardized quantifying method, as other techniques, such as Raman Spectroscopy or Thermo-extraction and desorption (TED) GC/MS, are also used [7][8][9][10], affects the quality of the data. The need of a standardized pre-treatment method for each matrix and the development of new ones for the study of new matrices to be able to accomplish a global dietary exposure assessment is also a great challenge. [7][9]

Fish [11][12][13], crustaceans and molluscs [14][15][16], drinking water [17][18], and salt are the main food categories with MPs occurrence data reports (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4). According to Danapoulos et al., most studies identified MPs contamination in seafood and reported MPs content <1 MPs/g. These authors reported that molluscs collected off the coasts of Asia were the most heavily contaminated (0−10.5 MPs/g), followed by crustaceans (0.1–8.6 MPs/g) and fish (0–2.9 MPs/g) [19]. In 2021, Jin et al. [20] demonstrated that aquatic food products (fish and bivalves) have a wide range of MPs levels (0–10.5 items/g for bivalves and 0–20 items/individual for fish). These same authors reported that drinking water and salt are also a pathway of MPs exposure to humans, with concentrations ranging from 0–61 particles/L in tap water, from 0–3074 MPs/L in bottled water, and from 0–13,629 particles/kg for salt [20][21]. However, MPs have been also being identified in other foods, such as sugar (249 ± 130 particles/kg), fruits (5.2 particles/100 g), vegetables (6.4 particles/100 g), cereals (5.7 particles/100 g), honey (1992–9752 particles/kg), meats (9.6 particles/100 g), dairy products (8.1 particles/100 g), soft drinks (40 ± 24.53 particles/L), tea (11 ± 5.26 particles/L), energy drinks (14 ± 5.79 particles/L), and beers (152 ± 50.97 particles/L) [7][9][22][23][24][25][26][27].

3. Hazard Characterization

Hazard characterization is the second step of any risk assessment and involves defining the nature of the adverse health effects associated with those biological, chemical, and physical agents that may be present in food. The hazard characterization should, if possible, involve an understanding of the doses involved and related responses [28]. As mentioned above, there are large knowledge gaps concerning the toxicokinetic, toxicodynamic, and toxicity effects of MPs in humans [29][30]. Therefore, the potential risks of dietary MPs to human health have been little explored. In other words, these knowledge gaps impede the estimation of food safety standards based on risk [2][31]. Therefore, more research in animals is needed to identify biomarkers of MPs toxicity, such as the disruption in immunity indices (acid phosphatase and alkaline phosphatase activity) and oxidative stress indices (total antioxidant capacity and malondialdehyde content) previously observed, for example, in juvenile and adult sea cucumbers [32][33]. Polyethylene microparticles have been shown to have an effect on haematological and biochemical indices, the antioxidant defence system, and expression of selected genes associated with the immune profile [34].

The size of MPs seems to have a relevant role in their toxicokinetic, as their gastrointestinal absorption has been observed to reach only 0.3% of ingested MPs and is limited to those MPs smaller than 1.5 µm [35][36]. Some evidence suggest that MPs are able to pass through the human placental barrier [37][38].

Regarding the toxicodynamic of these food pollutants, it is suspected that their action mechanism in humans is like that observed in animals [32]. Therefore, it is to be expected that the MPs could affect many molecular pathways [36][39], disrupt the genetic expression of oxidative stress control, and activate the E2 (Nrf) nuclear factor expression, among others. Alterations and changes in the oxidative stress, immune response, genomic instability, endocrine system alteration, neurotoxicity, reproductive abnormalities, embryotoxicity, and transgenerational toxicity, among others, may be a consequence of these action mechanisms [36].

Tissue abrasion, intestinal obstruction, chronic inflammation, body mass and metabolism reduction, neurotoxicity, behavior changes, cancer, fertility affectation, and mortality and morbidity increase, among many others, have been described as potential health effects associated with MP exposure [40][30][36][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49]. These results were obtained after the administration of different doses of MPs (0.001 mg/L and 10 mg/L for 10 days, 0.1% of food weight for 90 days, 396 MPs per 100 mg of food for 28 and 56 days, 0.1 g/L for 4 days, 110 particles/mL for 14 days, 5 particles per 1.5 g of feed for 8 months, among other doses) in fishes, bivalves, mice, and nematodes [36][41][42][43][44][47][48][49]. The oral intake of PS MPs has been specifically associated with the decrease of intestinal mucosa, the malfunction of the intestinal barrier, and changes in the biodiversity of the intestinal microbiota and metabolism [50].

4. Exposure assessment

Exposure assessment is third step in any risk assessment study. This step relates to a thorough evaluation of who or what has been exposed to a hazard and a quantification of the amounts involved [51]. The need to know the total dietary exposure and the contribution of the different dietary sources have aroused researchers’ interest in analysing and evaluating the MPs levels in the different food categories and assessing the dietary exposure in different scenarios.

The presence of MPs in drinking water has been confirmed by many studies in different locations and different types of waters (tap water, bottled, and groundwater). Oßmann et al. reported 2649 ± 2857 and 3074 ± 2531 particles of MPs/L in single-use plastic bottled water and glass bottled water, respectively [21]. The most common polymers found in drinking waters are PE ≈ PP > PS > PVC > PET [18], and the most frequent morphologies are fragments, fibres, films, foams, and pellets [18].

Some authors affirm that the dietary exposure to MPs from bottled water tends to be greater than from tap water [52][21].

In Saudi Arabia, given a mean average recommended water intake of 3.7 and 2.7 L per day for men and women, respectively, the corresponding daily exposure to MPs would be 0.1–0.2 particles/Kg bw. This estimated dietary exposure for high consumers of water increases to a daily exposure of 1.7–1.9 particles/Kg bw based on the WHO recommended intake for drinking water in hot climates [53].

Seafood has been identified as the main dietary source of these food contaminants. Therefore, and due to the nutritional importance of seafood consumption, addressing any knowledge gap related to seafood hazards is a critical priority [54]. The studies reviewed evinced the presence of theses pollutants in crustaceans, molluscs, and fish. There are studies reporting noteworthy levels: 287,527 particles/fish, 103–183 particles/fish, and 2.19 particles/individual [55][56][57].

In Europe, seafood consumption has been estimated at 25.8 kg per capita/year, which means 494.76 g/week or 70.68 g/day [58]. Considering the MPs levels in the molluscs and crustaceans and a 70.68 g/day portion, an estimated daily intake has been calculated for each type of seafood. A wide range of MPs intakes (0–212.04 particles/day) is observed. The EDI was only estimated for those types of seafood where the levels of MPs were reported in particles/g but not for those products where the units used were particles/individual. The highest intake levels of intakes are observed after the ingestion of Scotland coast mussels due to the high levels of MPs reported.

As mentioned above, the exposure assessment faces the challenge of a non-existing normalized unit system for MPs. Only the study from Charleston Harbour (USA) [59] reports the MPs levels in particles/g. Therefore, this is the only study reviewed here that provided the MPs levels necessary for the calculation of the estimated daily intake (EDI) (409.94 ± 113.09 particles/day) derived from the consumption of a daily fish portion of 70.68 g [58].

Comparing the MPs levels detected in bivalves and crustaceans (range: 0.15–3.2 particles/g) and the only study of MPs in fish expressed in particles/g (range: 5.8 ± 1.6 particles/g), the fish food category presents higher levels of MPs than crustaceans. That is the reason why the dietary exposure to MPs after ingesting the same portion size would expose the consumer to a higher intake of MPs when eating fish. However, the exposure to MPs derived from fish intake could be lowered in those scenarios where the fish is consumed after removing the gastrointestinal tract, liver, and gills, which are known to be the main locations of MPs in fish. The dietary exposure is expected to be lower, as these parts are usually discarded. In the case of ingestion of small fish consumed without discarding any of its content, all the MPs present in the individual are ingested, and the consumer is expected to be exposed to the total count of the MPs detected in the fish. Therefore, it is recommended that future MPs studies in fish report its MPs contents in the edible parts, so the dietary exposure estimation would be more accurate.

Salt is another food product where MPs levels have been analysed and detected worldwide. The occurrence of MPs in sea salt, rock salt, and lake salt demonstrate, as mentioned above, the ubiquity, diversity, and variability of MPs. Among all the data, the levels of MPs observed in salts from Croatia (27.13–31.68 particles/g) stand out [60].

Salt consumption in Europe has been estimated at 9.4 g/day [61]. Considering the reported MPs levels and this daily 9.4-g salt ingestion, an estimated daily intake (EDI) has been calculated for each type of salt. A wide range of MPs intakes derived from salt consumption has been observed (0.015–6.40 particles/day). Sea salt from China presented the highest total count of MPs (550–681 particles/kg) and therefore generated the greatest dietary exposure (5.17–6.40 particles/day). In the case of this food product, it was possible to calculate the EDI because all the studies reported the MPs levels using a normalized unit system of number of particles/g.

Some recent studies refer to the occurrence of MPs in other food groups, such as sugar (249 ± 130 particles/kg), fruits (5.2 particles/100 g), vegetables (6.4 particles/100 g), cereals (5.7 particles/100 g), honey (1992–9752 particles/kg), meats (9.6 particles/100 g), dairy products (8.1 particles/100 g), soft drinks (40 ± 24.53 particles/L), tea (11 ± 5.26 particles/L), energy drinks (14 ± 5.79 particles/L), and beers (152 ± 50.97 particles/L) [7][9][22][23][24][25][26][27], which had not yet been pointed as a dietary sources of MPs. MPs in agricultural soils create a potential impact on plants, including edible species, with relative concerns on food security [27]. Therefore, we suggest all food categories should be considered in the MPs dietary exposure assessment studies as any food group, if contaminated with quantifiable levels of MPs, may contribute to the total intake of MPs.

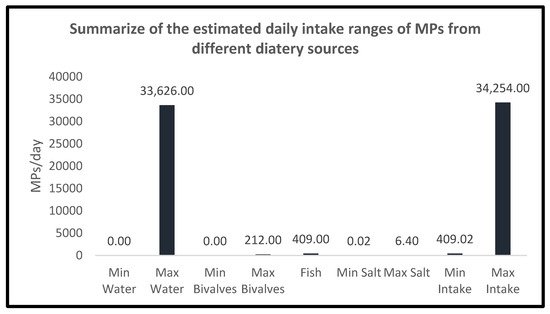

Even though, as stated above, the number of studies of MPs total dietary intake is low, Danopoulus et al. recently reported that the maximum annual human MPs uptake was estimated to be close to 55,000 MPs particles [19], which means an intake of 151 particles/day. In the present study, considering a consumption scenario where only the above-listed food categories (water, crustaceans and molluscs, fish, and salt) are included, and the upper intake of each one is considered, the MPs estimated dietary intake would be 34,254 particles/day (33,626 particles/day from 2 L/day of water, 212 particles/day from 70.68 g/day of crustaceans/molluscs, 409.94 particles/day from 70.68 g/day of fish, and 6.40 particles/day from 9.4 g/day of salt) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Summary of the MPs dietary intake ranges from each studied group.

There is no doubt that drinking-water data distorts the MPs dietary exposure estimation and suggests the need of developing, harmonizing, and standardizing not only a detection method for MPs but also the nomenclature to be used. The use of different nomenclatures in reporting the data not only makes the discussion and comparison of the results more difficult but also complicates the risk analysis derived from the dietary exposure to these growing pollutants.

5. Risk Characterization

Risk characterization is the final step of the risk assessment, in which the likelihood that a particular substance (MPs in this case) will cause harm is calculated in the light of the nature of the hazard and the extent to which people are exposed to it [62]. Some authors affirm that even though fish have been observed to be able to cope with the PE toxic effects, their consumption could pose serious health risks to humans [34]. However, as there are insufficient reference values to evaluate the MPs dietary intake, the MPs risk characterization for dietary MPs is not possible at present. In 2019, however, Stock et al. affirmed that their results suggested that the oral exposure to PS microplastic particles did not pose acute health risks to mammals, as the data from in-vivo studies did not provide any evidence of histologically detectable adverse effects [63]. In the same way, more recently, Almaiman et al. reported that the exposure to MPs from drinking water did not pose any concern to consumers in Saudi Arabia due to the low level of dietary intake of MPs from drinking water [53].

References

- Jambeck Jenna, R.; Roland, G.; Chris, W.; Siegler Theodore, R.; Miriam, P.; Anthony, A.; Ramani, N.; Law, K.L. Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science 2015, 347, 768–771.

- Alexy, P.; Anklam, E.; Emans, T.; Furfari, A.; Galgani, F.; Hanke, G.; Koelmans, A.; Pant, R.; Saveyn, H.; Sokull Kluettgen, B. Managing the analytical challenges related to micro- and nanoplastics in the environment and food: Filling the knowledge gaps. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2020, 37, 1–10.

- Patrício Silva, A.L.; Prata, J.C.; Walker, T.R.; Duarte, A.C.; Ouyang, W.; Barcelò, D.; Rocha-Santos, T. Increased plastic pollution due to COVID-19 pandemic: Challenges and recommendations. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 405, 126683.

- Jennifer, S.; Adyel Tanveer, M. Accumulation of plastic waste during COVID-19. Science 2020, 369, 1314–1315.

- Akhbarizadeh, R.; Dobaradaran, S.; Nabipour, I.; Tangestani, M.; Abedi, D.; Javanfekr, F.; Jeddi, F.; Zendehboodi, A. Abandoned COVID-19 personal protective equipment along the Bushehr shores, the Persian Gulf: An emerging source of secondary microplastics in coastlines. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 168, 112386.

- EFSA. Glossary. Hazar Identification. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/glossary/hazard-identification (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Kwon, J.; Kim, J.; Pham, T.D.; Tarafdar, A.; Hong, S.; Chun, S.; Lee, S.; Kang, D.; Kim, J.; Kim, S.; et al. Microplastics in Food: A Review on Analytical Methods and Challenges. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6710.

- Ivleva, N.P. Chemical Analysis of Microplastics and Nanoplastics: Challenges, Advanced Methods, and Perspectives. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 11886–11936.

- Bai, C.; Liu, L.; Hu, Y.; Zeng, E.Y.; Guo, Y. Microplastics: A review of analytical methods, occurrence and characteristics in food, and potential toxicities to biota. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 150263.

- Vivekanand, A.C.; Mohapatra, S.; Tyagi, V.K. Microplastics in aquatic environment: Challenges and perspectives. Chemosphere 2021, 282, 131151.

- Pellini, G.; Gomiero, A.; Fortibuoni, T.; Ferrà, C.; Grati, F.; Tassetti, A.N.; Polidori, P.; Fabi, G.; Scarcella, G. Characterization of microplastic litter in the gastrointestinal tract of Solea solea from the Adriatic Sea. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 234, 943–952.

- Herrera, A.; Ŝtindlová, A.; Martínez, I.; Rapp, J.; Romero-Kutzner, V.; Samper, M.D.; Montoto, T.; Aguiar-González, B.; Packard, T.; Gómez, M. Microplastic ingestion by Atlantic chub mackerel (Scomber colias) in the Canary Islands coast. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 139, 127–135.

- Neves, D.; Sobral, P.; Ferreira, J.L.; Pereira, T. Ingestion of microplastics by commercial fish off the Portuguese coast. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 101, 119–126.

- Renzi, M.; Guerranti, C.; Blašković, A. Microplastic contents from maricultured and natural mussels. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 131, 248–251.

- Cho, Y.; Shim, W.J.; Jang, M.; Han, G.M.; Hong, S.H. Abundance and characteristics of microplastics in market bivalves from South Korea. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 245, 1107–1116.

- Catarino, A.I.; Macchia, V.; Sanderson, W.G.; Thompson, R.C.; Henry, T.B. Low levels of microplastics (MP) in wild mussels indicate that MP ingestion by humans is minimal compared to exposure via household fibres fallout during a meal. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 237, 675–684.

- Welle, F.; Franz, R. Microplastic in bottled natural mineral water—literature review and considerations on exposure and risk assessment. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2018, 35, 2482–2492.

- Koelmans, A.A.; Mohamed Nor, N.H.; Hermsen, E.; Kooi, M.; Mintenig, S.M.; De France, J. Microplastics in freshwaters and drinking water: Critical review and assessment of data quality. Water Res. 2019, 155, 410–422.

- Danopoulos, E.; Jenner, L.C.; Twiddy, M.; Rotchell, J.M. Microplastic Contamination of Seafood Intended for Human Consumption: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environ. Health Perspect. 2020, 128, 126002.

- Jin, M.; Wang, X.; Ren, T.; Wang, J.; Shan, J. Microplastics contamination in food and beverages: Direct exposure to humans. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 2816–2837.

- Oßmann, B.E.; Sarau, G.; Holtmannspötter, H.; Pischetsrieder, M.; Christiansen, S.H.; Dicke, W. Small-sized microplastics and pigmented particles in bottled mineral water. Water Res. 2018, 141, 307–316.

- Dekimpe, M.; De Witte, B.; Deloof, D.; Hostens, K.; Van Loco, J.; Andjelkovic, M.; Van Hoeck, E.; Robbens, J. Dietary Exposure of the Belgian Population to Microplastics Through a Diverse Food Basket. In Proceedings of the Scientific Colloquium N°25: A Coordinated Approach to Assess Human Health Risks of Micro-and Nanoplastics in Food, Parma, Italy, 6–7 May 2021.

- Kutralam-Muniasamy, G.; Pérez-Guevara, F.; Elizalde-Martínez, I.; Shruti, V.C. Branded milks—Are they immune from microplastics contamination? Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 714, 6823.

- Huang, Y.; Chapman, J.; Deng, Y.; Cozzolino, D. Rapid measurement of microplastic contamination in chicken meat by mid infrared spectroscopy and chemometrics: A feasibility study. Food Control. 2020, 113, 107187.

- Oliveri Conti, G.; Ferrante, M.; Banni, M.; Favara, C.; Nicolosi, I.; Cristaldi, A.; Fiore, M.; Zuccarello, P. Micro- and nano-plastics in edible fruit and vegetables. The first diet risks assessment for the general population. Environ. Res. 2020, 187, 109677.

- Shruti, V.C.; Pérez-Guevara, F.; Elizalde-Martínez, I.; Kutralam-Muniasamy, G. First study of its kind on the microplastic contamination of soft drinks, cold tea and energy drinks—Future research and environmental considerations. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 726, 138580.

- Campanale, C.; Galafassi, S.; Savino, I.; Massarelli, C.; Ancona, V.; Volta, P.; Uricchio, V.F. Microplastics pollution in the terrestrial environments: Poorly known diffuse sources and implications for plants. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 805, 150431.

- EFSA. Glossary. Hazard Characterization. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/glossary/hazard-characterisation (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Rubio Armendáriz, C.; Daschner, Á.; González Fandos, E.; González Muñoz, M.J.; Moreno-Arribas, M.V.; Talens Oliag, P.; de Castro, G.; Bustos, J. Informe del comité científico de la agencia española de seguridad alimentaria y nutrición (AESAN) sobre la presencia y la seguridad de los plásticos como contaminantes en los alimentos. Agencia Española Segur. Aliment. Nutr. (AESAN) 2019, 30, 49–84.

- Prata, J.C.; da Costa, J.P.; Lopes, I.; Duarte, A.C.; Rocha-Santos, T. Environmental exposure to microplastics: An overview on possible human health effects. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 702, 134455.

- Hantoro, I.; Löhr, A.J.; Van Belleghem, F.G.A.J.; Widianarko, B.; Ragas, A.M.J. Microplastics in coastal areas and seafood: Implications for food safety. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2019, 36, 674–711.

- Usman, S.; Abdull Razis, A.F.; Shaari, K.; Amal, M.N.; Saad, M.Z.; Mat Isa, N.; Nazarudin, M.F.; Zulkifli, S.Z.; Sutra, J.; Ibrahim, M.A. Microplastics Pollution as an Invisible Potential Threat to Food Safety and Security, Policy Challenges and the Way Forward. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9591.

- Mohsen, M.; Zhang, L.; Sun, L.; Lin, C.; Wang, Q.; Liu, S.; Sun, J.; Yang, H. Effect of chronic exposure to microplastic fibre ingestion in the sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 209, 111794.

- Hodkovicova, N.; Hollerova, A.; Caloudova, H.; Blahova, J.; Franc, A.; Garajova, M.; Lenz, J.; Tichy, F.; Faldyna, M.; Kulich, P.; et al. Do foodborne polyethylene microparticles affect the health of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss)? Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 793, 148490.

- EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain, (CONTAM) Presence of microplastics and nanoplastics in food, with particular focus on seafood. EFSA J. 2016, 14, e04501.

- Alimba, C.G.; Faggio, C. Microplastics in the marine environment: Current trends in environmental pollution and mechanisms of toxicological profile. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2019, 68, 61–74.

- Ragusa, A.; Svelato, A.; Santacroce, C.; Catalano, P.; Notarstefano, V.; Carnevali, O.; Papa, F.; Rongioletti, M.C.A.; Baiocco, F.; Draghi, S.; et al. Plasticenta: First evidence of microplastics in human placenta. Environ. Int. 2021, 146, 106274.

- Fournier, S.B.; D’Errico, J.N.; Adler, D.S.; Kollontzi, S.; Goedken, M.J.; Fabris, L.; Yurkow, E.J.; Stapleton, P.A. Nanopolystyrene translocation and fetal deposition after acute lung exposure during late-stage pregnancy. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2020, 17, 1–11.

- Avio, C.G.; Gorbi, S.; Regoli, F. Plastics and microplastics in the oceans: From emerging pollutants to emerged threat. Mar. Environ. Res. 2017, 128, 2–11.

- Barboza, L.G.A.; Dick Vethaak, A.; Lavorante, B.R.B.O.; Lundebye, A.; Guilhermino, L. Marine microplastic debris: An emerging issue for food security, food safety and human health. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 133, 336–348.

- Pedà, C.; Caccamo, L.; Fossi, M.C.; Gai, F.; Andaloro, F.; Genovese, L.; Perdichizzi, A.; Romeo, T.; Maricchiolo, G. Intestinal alterations in European sea bass Dicentrarchus labrax (Linnaeus, 1758) exposed to microplastics: Preliminary results. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 212, 251–256.

- Rodriguez-Seijo, A.; Lourenço, J.; Rocha-Santos, T.A.P.; da Costa, J.; Duarte, A.C.; Vala, H.; Pereira, R. Histopathological and molecular effects of microplastics in Eisenia andrei Bouché. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 220, 495–503.

- Guzzetti, E.; Sureda, A.; Tejada, S.; Faggio, C. Microplastic in marine organism: Environmental and toxicological effects. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2018, 64, 164–171.

- Wang, W.; Gao, H.; Jin, S.; Li, R.; Na, G. The ecotoxicological effects of microplastics on aquatic food web, from primary producer to human: A review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 173, 110–117.

- Xie, X.; Deng, T.; Duan, J.; Xie, J.; Yuan, J.; Chen, M. Exposure to polystyrene microplastics causes reproductive toxicity through oxidative stress and activation of the p38 MAPK signaling pathway. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 190, 110133.

- Wang, Y.; Huang, J.; Zhu, F.; Zhou, S. Airborne Microplastics: A Review on the Occurrence, Migration and Risks to Humans. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2021, 657–664.

- Karbalaei, S.; Hanachi, P.; Rafiee, G.; Seifori, P.; Walker, T.R. Toxicity of polystyrene microplastics on juvenile Oncorhynchus mykiss (rainbow trout) after individual and combined exposure with chlorpyrifos. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 403, 123980.

- Yu, S.; Chan, B.K.K. Intergenerational microplastics impact the intertidal barnacle Amphibalanus amphitrite during the planktonic larval and benthic adult stages. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 267, 115560.

- Umamaheswari, S.; Priyadarshinee, S.; Bhattacharjee, M.; Kadirvelu, K.; Ramesh, M. Exposure to polystyrene microplastics induced gene modulated biological responses in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Chemosphere 2021, 281, 128592.

- Jin, Y.; Lu, L.; Tu, W.; Luo, T.; Fu, Z. Impacts of polystyrene microplastic on the gut barrier, microbiota and metabolism of mice. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 649, 308–317.

- EFSA. Glossary. Exposure Assessment. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/glossary/exposure-assessment (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Cox, K.D.; Covernton, G.A.; Davies, H.L.; Dower, J.F.; Juanes, F.; Dudas, S.E. Human Consumption of Microplastics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 7068–7074.

- Almaiman, L.; Aljomah, A.; Bineid, M.; Aljeldah, F.M.; Aldawsari, F.; Liebmann, B.; Lomako, I.; Sexlinger, K.; Alarfaj, R. The occurrence and dietary intake related to the presence of microplastics in drinking water in Saudi Arabia. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2021, 193, 390–399.

- Smith, M.; Love, D.C.; Rochman, C.M.; Neff, R.A. Microplastics in Seafood and the Implications for Human Health. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2018, 5, 375–386.

- Cho, Y.; Shim, W.J.; Jang, M.; Han, G.M.; Hong, S.H. Nationwide monitoring of microplastics in bivalves from the coastal environment of Korea. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 270, 116175.

- Shabaka, S.H.; Marey, R.S.; Ghobashy, M.; Abushady, A.M.; Ismail, G.A.; Khairy, H.M. Thermal analysis and enhanced visual technique for assessment of microplastics in fish from an Urban Harbor, Mediterranean Coast of Egypt. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 159, 111465.

- O’Connor, J.D.; Murphy, S.; Lally, H.T.; O’Connor, I.; Nash, R.; O’Sullivan, J.; Bruen, M.; Heerey, L.; Koelmans, A.A.; Cullagh, A.; et al. Microplastics in brown trout (Salmo trutta Linnaeus, 1758) from an Irish riverine system. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 267, 115572.

- Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries (European Commision). EUMOFA EU Consumer Habits Regarding Fishery and Aquaulture Products-Final Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021.

- Parker, B.W.; Beckingham, B.A.; Ingram, B.C.; Ballenger, J.C.; Weinstein, J.E.; Sancho, G. Microplastic and tire wear particle occurrence in fishes from an urban estuary: Influence of feeding characteristics on exposure risk. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 160, 111539.

- Renzi, M.; Blašković, A. Litter & microplastics features in table salts from marine origin: Italian versus Croatian brands. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 135, 62–68.

- Directorate-General Health and Consumers (European Commision). Implementation of the EU Salt Reduction Framework Results of Member States survey Health and Consumers; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2012.

- EFSA. Glossary. Risk Characterisation. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/glossary/risk-characterisation (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Stock, V.; Böhmert, L.; Lisicki, E.; Block, R.; Cara-Carmona, J.; Pack, L.K.; Selb, R.; Lichtenstein, D.; Voss, L.; Henderson, C.J.; et al. Uptake and effects of orally ingested polystyrene microplastic particles in vitro and in vivo. Arch. Toxicol. 2019, 93, 1817–1833.

- Sana, S.S.; Dogiparthi, L.K.; Gangadhar, L.; Chakravorty, A.; Abhishek, N. Effects of microplastics and nanoplastics on marine environment and human health. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 44743–44756.

More

Information

Subjects:

Food Science & Technology

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

825

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

27 Jan 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No