Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Zhongzhou Chen | + 2245 word(s) | 2245 | 2022-01-26 03:38:34 | | | |

| 2 | Amina Yu | Meta information modification | 2245 | 2022-01-27 01:40:55 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Chen, Z. Helicoverpa armigera Pheromone-Binding Protein PBP1. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18826 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Chen Z. Helicoverpa armigera Pheromone-Binding Protein PBP1. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18826. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Chen, Zhongzhou. "Helicoverpa armigera Pheromone-Binding Protein PBP1" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18826 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Chen, Z. (2022, January 26). Helicoverpa armigera Pheromone-Binding Protein PBP1. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18826

Chen, Zhongzhou. "Helicoverpa armigera Pheromone-Binding Protein PBP1." Encyclopedia. Web. 26 January, 2022.

Copy Citation

Cotton bollworm (Helicoverpa armigera) is a worldwide agricultural pest in which the transport of pheromones is indispensable and perceived by pheromone-binding proteins (PBPs).

Helicoverpa armigera

pheromone-binding protein

crystal structure

ligand binding and releasing mechanism

complex

acidic pH

(Z)-9-hexadecenal

pheromones

mechanistic insights

fluorescence binding assays

1. Introduction

Insects have evolved a sensitive olfactory system to detect information-rich odor molecules for their survival and reproduction [1]. The initial step of odorant recognition involves binding odorant molecules to the odorant binding proteins (OBPs) and carrying them to odorant receptors (ORs). These OBPs may serve as molecular targets for attracting moths or other insect species [1][2]. Lepidoptera OBPs have been divided into pheromone-binding proteins (PBPs) and general OBPs (GOBPs) [3].

Many insect PBPs structures have been solved both in the crystal forms and in solution since the first crystal structure of silkworm moth BmorPBP/bombykol complex was reported [4][5][6][7][8]. These structures exhibit many identical characteristics, including six or seven α-helices, three strictly conserved disulfide bridges, and a hydrophobic binding pocket. However, growing evidence suggested that these insect PBPs have significant differences in ligand binding and releasing mechanisms because of their different cavity shapes and openings. The NMR structure of silkworm moth BmorPBP proved that the C terminal dodecapeptide segment of the acidic BmorPBP structure (pH 4.5) formed an additional α-helix in the protein core, occupying the corresponding pheromone-binding site and extruding ligands [5][9] (Figure S1A). The study suggested that the C-terminal region plays a key role by forming a helical structure to replace the corresponding pheromone-binding pocket at low pH. Moreover, at neutral pH, the additional helix withdraws from the binding pocket and favors pheromone binding [2]. pH-triggered conformational switch involving histidine(s) protonation/deprotonation is a regulatory mechanism [10]. The potential importance of the histidine residues for PBP function was first suggested in B. mori on the basis of histidine positions in the crystal structure [5]. Interestingly, His69, His70, and His95 are identical in lepidopteran PBPs and GOBPs, suggesting that pH-triggered conformational switch may be conserved for the entire order.

The interactions between ligands and insect OBPs have also been proposed. The structure of BmorPBP/bombykol complex revealed that Ser56 specifically interacts with the ligand in the binding pocket [5]. Other research on A. polyphemus PBP indicates that Trp37 may play an important role in the initial interaction with the ligand, while Asn53 plays a critical role in the specific recognition of pheromones [10][11].

In H. armigera, three PBPs were identified, and their abilities to bind five pheromone components were measured by fluorescence-binding assay [12]. It was shown that HarmPBP1 binds the two principal pheromone components with strong affinities. However, there was no three-dimensional structural information reported on HarmPBPs.

2. Crystal Structures of Apo-HarmPBP1 and HarmPBP1/Z9-16:Ald Complex

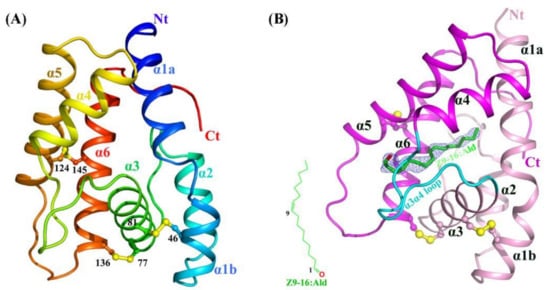

HarmPBP1 was successfully expressed in bacteria and then purified through Ni-affinity chromatography, ion exchange chromatography, and size-exclusion chromatography (see the Methods and Materials). The highly purified protein (Figure S2A) produced small but regular crystals in crystallization trials. After optimizing crystallization conditions, it succeeded in obtaining crystals. The apo-HarmPBP1 structure at pH 7.5 was determined by molecular replacement and refined to a resolution of 1.3 Å in the space group of P21, with an Rwork of 17.9% and an Rfree of 19.8%. The cloned protein was 144 residues long and possessed six cysteine residues. The structure was built in the electron density map, except for the C-terminal residues 159-170. The HarmPBP1 scaffold contains three conserved disulfide bonds linking α-helices α1 and α3 (Cys46-Cys81), α3 and α6 (Cys77-Cys136), and α5 and α6 (Cys124-Cys145) (Figure 1A), encapsulating the hydrophobic pocket for pheromones binding.

Figure 1. Crystal structures of apo and Z9-16:Ald-bound HarmPBP1. (A) Ribbon representation of apo-HarmPBP1 with rainbow coloring mode. (B) The Z9-16:Ald-bound HarmPBP1 structure. The chemical structure of Z9-16:Ald (green) is shown in the bottom left. The differential electron density for the Z9-16:Ald in a Fo-Fc map is contoured at 2.5 σ (light blue). Disulfide bridges, yellow; α3α4 loop, cyan; Nt: N-terminus, Ct: C-terminus.

On the basis of the affinity data of HarmPBP1 to different pheromone components [12], Z9-16:Ald and Z11-16:Ald with the strongest affinity for complex crystallization trials were chose. Through a series of cocrystallization experiments, we eventually obtained cocrystals of HarmPBP1 with Z9-16:Ald, probably because Z9-16:Ald bound slightly stronger than Z11-16:Ald. HarmPBP1/Z9-16:Ald complex crystal had different morphologies from that of the apo-HarmPBP1, indicating the formation of the complex with ligand Z9-16:Ald. A dataset were collected at 2.09 Å resolution. The binding of Z9-16:Ald was confirmed by the differential electron density (Figure 1B), and the crystal packing between the apo at pH 7.5 and the complex was different. The overall structure of the complex was similar to the apo-HarmPBP1, and the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) between these two structures was as low as 0.4 Å. Structural variation was only observed in a few loop regions (Figure S2B), showing that they were almost identical. The most prominent structural changes were the loop between α3 and α4 (α3α4 loop), with a 0.7 Å shift and the loop between α5 and α6 (α5α6 loop) with a 1.9 Å shift. Moreover, an additional three residues were solved in the C-terminus.

3. Structural Comparison Revealed a Specific Conformation of Apo-HarmPBP1

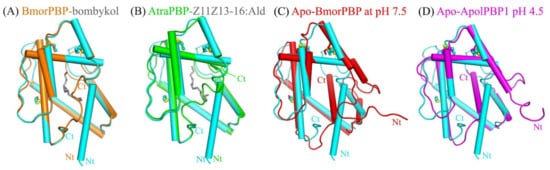

A Dali server search of the apo-HarmPBP1 structure identified BmorPBP-bombykol (PDB 1DQE, Z = 23.5, RMSD = 1.0 Å) and AtraPBP1-Z11Z13-16:Ald (PDB 4INW, Z = 22.4, RMSD = 1.2 Å) [5][13] as the closest structural homologs (Figure 2 ). Surprisingly, the structural similarity between apo-HarmPBP1 and all other apo-GOBPs or apo-PBPs was lower as the RMSD was larger than 1.5 Å, revealing a distinct conformation of apo-HarmPBP1 compared with other apo-PBPs.

Figure 2. Superimposition of apo-HarmPBP1 (cyan) on selected OBPs. (A) BmorPBP-bombykol (PDB: 1DQE, orange). (B) AtraPBP-Z11Z13-16:Ald (PDB: 4INW, green). (C) apo-BmorPBP at pH 7.5 (PDB: 2FJY, red). (D) Apo-ApolPBP1 at pH 4.5 (PDB: 2JPO, magenta). Conserved disulfide bonds (yellow) are shown in ball-stick modes. Ligands, gray.

The secondary structures of HarmPBP1 are quite similar to those of BmorPBP in Bombyx mori [5][9][14], ApolPBP1 in Antheraea polyphemus [10], and AtraPBP1 in Amyelois transitella [13] (Figure S3). The most significant structural differences between apo-HarmPBP1 and other known insect PBPs were observed at the C terminus. The last 12 residues were missed in the structure of apo-HarmPBP1, which might have been a result of crystal packing. Both BmorPBP-bombykol (PDB ID:1DQE) and AtraPBP1-Z11Z13-16:Ald (PDB ID: 4INW) had a C-terminal loop [5][13], while a C-terminal helix was found in the apo-BmorPBP at pH 7.5 (PDB ID: 2FJY) and ApolPBP1 at pH 4.5 (PDB ID: 2JPO) [9][10] (Figure 2). Then, HarmPBP1 with these two types of PBPs mentioned above were compared. The high structural similarity between HarmPBP1/Z9-16:Ald complex and BmorPBP-bombykol or AtraPBP1-Z11Z13-16:Ald complex (Figure 2) suggests that they may share a similar ligand-binding mode. However, the conformations of both termini as well as some loops differed significantly between apo-HarmPBP1 and the apo-BmorPBP/apo-ApolPBP1 (Figure 2C,D). The first helix of HarmPBP1 occupied the C-terminal helix position of the above two structures. Moreover, the seventh helix of the latter was located in the protein core. Finally, for BmorPBP and AtraPBP1, the structural changes between the apo and its corresponding complex were evident (comparing Figure 2A with Figure 2C), but it was subtle for HarmPBP1 (Figure S2B).

4. The Binding of Ligand in the HarmPBP1 Binding Cavity

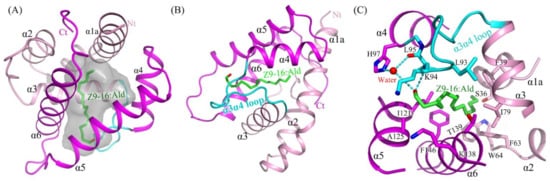

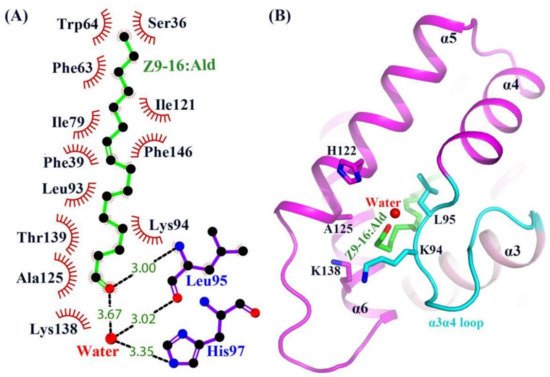

The structure of HarmPBP1 was found to contain a hydrophobic cavity formed by the five helices α1, α3, α4, α5, and α6. The cavity volume of the HarmPBP1 complex was 206 Å3. The cavity had a “C”-shape (Figure 3A), and the ligand Z9-16:Ald fitted perfectly inside the cavity (Figure 3B). The HarmPBP1/Z9-16:Ald complex contained a single molecule of Z9-16:Ald that was stabilized primarily by an array of hydrophobic interactions, which were mediated by the side-chains of Phe63, Ile79, Leu93, Leu95, Ile121, and Phe146 (Figure 3C). In addition, a stacked arrangement of phenylalanines at positions 39 and 146 interacted with the ligand near the desaturated carbons (Figure 3B,C). The five aromatic residues Phe39, Phe63, Trp64, Phe103, and Phe146 were strictly conserved in all known lepidopteran PBPs (Figure S3). These residues and the shape of the cavity were therefore likely responsible for the specific binding of the unsaturated aliphatic odorant molecules. Moreover, Ser36 and Thr139 also interacted with Z9-16:Ald through van der Waals contacts.

Figure 3. The binding pocket and its binding site details. (A) HarmPBP1 has a “C” shaped ligand-binding cavity. (B) The binding of Z9-16:Ald (green) in the HarmPBP1 binding pocket. (C) Detailed interaction of Z9-16:Ald. Hydrogen bonds, dashed lines. α3α4 loop, cyan.

Except for the main hydrophobic interaction, hydrogen bonds were also observed in the HarmPBP1/Z9-16:Ald complex. The oxygen atom of the ligand aldehyde group formed a hydrogen bond with the main chain of Leu95. The aldehyde group also bound Leu95 and His97 through weak water-mediated hydrogen bonds (Figure 3C and Figure 4A). Moreover, Leu95 and His97 were conserved in other homologous pheromone-binding proteins (Figure S3), and these conservations may play a key role in pheromone binding (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Structure of the Z9-16:Ald bound state of HarmPBP1. (A) LIGPLOT diagram [15] of Z9-16:Ald. Hydrogen bonds are represented by dashed lines and hydrophobic contacts by arcs with radiating spokes. Atoms involved in hydrophobic contacts are represented by black circles. (B) Ribbon diagram of HarmPBP1. A single Z9-16:Ald molecule (green) binds in the central cavity and enters through an opening formed by α5, α6, and the α3α4 loop.

In the apo-HarmPBP1, there was a channel through the ligand binding pocket (Figure S4A). However, one opening was covered in the HarmPBP1/Z9-16:Ald complex (Figure 1B and Figure S4B), because three C-terminal additional residues were solved and Leu161 occupied the opening. These three residues adopted a loop conformation that was greatly different from those in the complex of BmorPBP-bombykol and AtraPBP-Z11Z13-16:Ald [5][13]. Although the C-terminal residue Leu161 was somewhat away (5.6 Å) from the ligand, it had hydrophobic interactions with side-chains of Phe63, Phe60, and Ser36 and thus stabilized the hydrophobic binding pocket. The only one opening in the HarmPBP1/Z9-16:Ald complex was surrounded by helices α5, α6, and the α3α4 loop (Figure S4B). The Z9-16:Ald was in an elongated conformation, with one end entering the cavity through the opening formed by His122, Ala125 in α5, Lys138 in α6, and Lys94 and Leu95 in α3α4 loop (Figure 4B). In the apo-HarmPBP1 structure, part of the Lys138 side chain was flexible (Figure S4A). The binding of Z9-16:Ald induced conformational changes of Lys94 and Lys138 side chains and significantly hindered the access of the ligand to the solvent (Figure S4B). Thus, it was hypothesized that the entry of ligand into the pocket is followed by a shift of Lys94 and Lys138, which act as a lid. The conformational rearrangements might trigger the lid to cover the opening of the pocket.

5. A New Releasing Mechanism at Low pH Conditions

Various studies [5][10][13] suggested significant pH-dependent conformational changes in lepidopteran PBPs. The C-terminus would form an additional helix α7 under low pH conditions, occupying the corresponding pheromone binding pocket. To know whether HarmPBP1 has a similar mechanism, it solved the structure of the apo-HarmPBP1 at acid conditions. Surprisingly, the conformations of the apo-HarmPBP1 at pH 5.5 were very similar to those at pH 7.5 with an overall RMSD of 0.5 Å. Therefore, the above-mentioned significant structural changes influenced by pH may not exist in HarmPBP1. Moreover, no C-terminal additional α-helix was observed, and no residues were found in the cavity at pH 5.5. The cavity volume of the HarmPBP1 decreased from 266 Å3 to 211 Å3 when the pH changed from 7.5 to 5.5. The smaller cavity in HarmPBP1 would be not enough to accommodate an additional helix α7, which is found in other PBPs under low pH conditions [5][10][13].

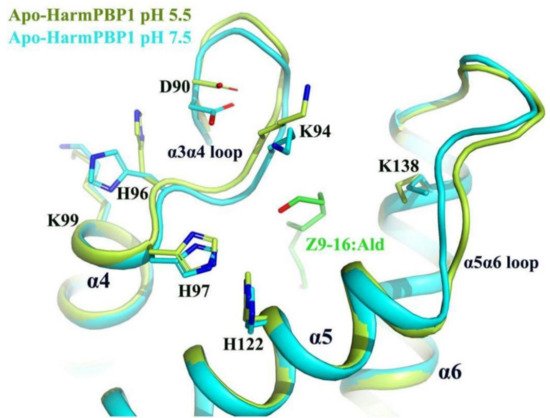

Nevertheless, our structures uncovered a new releasing mechanism at low pH conditions. There were three residues (His96, His97, His122) that were strictly conserved across all known lepidopteran PBPs, suggesting that their role in the PBP function may be similar (Figure S3). A decrease of pH from 7.5 to 5.5 would result in the protonation of the imidazole rings of His96, His97, and His122 (Figure 5), which were in close contact, and therefore mutual repulsion probably would occur. Moreover, protonation changed the position of His96, which in turn increased its interaction with Asp90 located at the α3α4 loop and simultaneously increased its repulsive ability with Lys99. These changes triggered the movement of the α3α4 loop about 1.0 Å, enabling a larger opening of the pocket at pH 5.5 (Figure 5). In addition, the α5α6 loop around the opening also moved out about 1.5 Å. These movements might increase the interacting distance between the protein and the ligand. Therefore, the binding ability of HarmPBP1 to its ligand was weaker at low pH, and the fluorescence-binding experiment also proved this. The affinity of HarmPBP1 to Z9-16:Ald and Z11-16:Ald was measured under neutral (pH 7.5) and acidic (pH 5.5) conditions, respectively. HarmPBP1 showed a higher binding affinity to a nonspecific ligand 1-NPN at pH 7.5 (1.79 ± 0.14 μM) than at pH 5.5 (4.49 ± 0.41 μM) (Figure S5A). Further competitive binding assays showed that HarmPBP1 exhibited reduced binding activity for two principal pheromones Z11-16:Ald and Z9-16:Ald at low pH. In summary, it is believed that the α3α4 loop, providing an entrance for the ligand, becomes destabilized upon protonation of one or all of three histidine residues at low pH.

Figure 5. Superimposition of apo-HarmPBP1 at pH 5.5 (limon) on apo-HarmPBP1 at pH 7.5 (cyan). The side chain of His96 in the α3α4 loop changed greatly due to the protonation. The α3α4 loop and the α5α6 loop of the HarmPBP1 at pH 5.5 moved outward so that the pocket formed a larger opening. Z9-16:Ald (green) was docked from the HarmPBP1/Z9-16:Ald complex after superimposition.

References

- Leal, W.S.; Ishida, Y.; Pelletier, J.; Xu, W.; Rayo, J.; Xu, X.; Ames, J.B. Olfactory proteins mediating chemical communication in the navel orangeworm moth, Amyelois transitella. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e7235.

- Leal, W.S.; Barbosa, R.M.; Xu, W.; Ishida, Y.; Syed, Z.; Latte, N.; Chen, A.M.; Morgan, T.I.; Cornel, A.J.; Furtado, A. Reverse and conventional chemical ecology approaches for the development of oviposition attractants for Culex mosquitoes. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3045.

- Vogt, R.G.; Prestwich, G.D.; Lerner, M.R. Odorant-binding-protein subfamilies associate with distinct classes of olfactory receptor neurons in insects. J. Neurobiol. 1991, 22, 74–84.

- Tegoni, M.; Campanacci, V.; Cambillau, C. Structural aspects of sexual attraction and chemical communication in insects. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2004, 29, 257–264.

- Sandler, B.H.; Nikonova, L.; Leal, W.S.; Clardy, J. Sexual attraction in the silkworm moth: Structure of the pheromone-binding-protein-bombykol complex. Chem. Biol. 2000, 7, 143–151.

- Xu, X.; Xu, W.; Rayo, J.; Ishida, Y.; Leal, W.S.; Ames, J.B. NMR structure of navel orangeworm moth pheromone-binding protein (AtraPBP1): Implications for pH-sensitive pheromone detection. Biochemistry 2010, 49, 1469–1476.

- Zhou, J.J.; Robertson, G.; He, X.; Dufour, S.; Hooper, A.M.; Pickett, J.A.; Keep, N.H.; Field, L.M. Characterisation of Bombyx mori odorant-binding proteins reveals that a general odorant-binding protein discriminates between sex pheromone components. J. Mol. Biol. 2009, 389, 529–545.

- Zubkov, S.; Gronenborn, A.M.; Byeon, I.J.; Mohanty, S. Structural consequences of the pH-induced conformational switch in A.polyphemus pheromone-binding protein: Mechanisms of ligand release. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 354, 1081–1090.

- Lautenschlager, C.; Leal, W.S.; Clardy, J. Coil-to-helix transition and ligand release of Bombyx mori pheromone-binding protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 335, 1044–1050.

- Damberger, F.F.; Ishida, Y.; Leal, W.S.; Wuthrich, K. Structural basis of ligand binding and release in insect pheromone-binding proteins: NMR structure of Antheraea polyphemus PBP1 at pH 4.5. J. Mol. Biol. 2007, 373, 811–819.

- Mohanty, S.; Zubkov, S.; Gronenborn, A.M. The solution NMR structure of Antheraea polyphemus PBP provides new insight into pheromone recognition by pheromone-binding proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2004, 337, 443–451.

- Zhang, T.T.; Mei, X.D.; Feng, J.N.; Berg, B.G.; Zhang, Y.J.; Guo, Y.Y. Characterization of three pheromone-binding proteins (PBPs) of Helicoverpa armigera (Hubner) and their binding properties. J. Insect Physiol. 2012, 58, 941–948.

- Di Luccio, E.; Ishida, Y.; Leal, W.S.; Wilson, D.K. Crystallographic observation of pH-induced conformational changes in the Amyelois transitella pheromone-binding protein AtraPBP1. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53840.

- Lautenschlager, C.; Leal, W.S.; Clardy, J. Bombyx mori pheromone-binding protein binding nonpheromone ligands: Implications for pheromone recognition. Structure 2007, 15, 1148–1154.

- Wallace, A.C.; Laskowski, R.A.; Thornton, J.M. LIGPLOT: A program to generate schematic diagrams of protein-ligand interactions. Protein Eng. 1995, 8, 127–134.

More

Information

Subjects:

Agriculture, Dairy & Animal Science

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

585

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

27 Jan 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No