Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Haichun Gao | + 3655 word(s) | 3655 | 2022-01-25 08:00:34 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 3655 | 2022-01-26 02:40:51 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Gao, H. Heme-Copper Oxidases with Nitrite and Nitric Oxide. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18768 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Gao H. Heme-Copper Oxidases with Nitrite and Nitric Oxide. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18768. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Gao, Haichun. "Heme-Copper Oxidases with Nitrite and Nitric Oxide" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18768 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Gao, H. (2022, January 25). Heme-Copper Oxidases with Nitrite and Nitric Oxide. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18768

Gao, Haichun. "Heme-Copper Oxidases with Nitrite and Nitric Oxide." Encyclopedia. Web. 25 January, 2022.

Copy Citation

Nitrite and nitric oxide (NO), two active and critical nitrogen oxides linking nitrate to dinitrogen gas in the broad nitrogen biogeochemical cycle, are capable of interacting with redox-sensitive proteins. The interactions of both with heme-copper oxidases (HCOs) serve as the foundation not only for the enzymatic interconversion of nitrogen oxides but also for the inhibitory activity.

nitrite

nitric oxide

heme-copper oxidase

1. Introduction

Proton motive force (pmf) is essential for bacteria to grow and survive under non-replicating conditions by providing energy for a wide range of crucial processes [1][2][3]. The pmf (electrochemical potential) consists of two gradients: the chemical proton or pH gradient (∆pH) and the membrane potential generated by the transport of electrical charge (∆ψ). Bacteria are capable of generating the pmf by a variety of mechanisms; among them, the most efficient one is through oxygen reduction [3]. The oxygen-reducing enzymes (terminal oxidases) that contribute to the pmf generation are classified into two main groups: heme-copper oxidase (HCO) (also called heme-copper oxygen reductase (HCOR)) superfamily and bd-type quinol oxidase (bd QO) family [4][5].

The HCO superfamily is composed of three subfamilies, A, B, and C, as well as the structurally-related nitric oxide (NO) reductases (NOR) [6][7]. A-family HCOs include cytochrome c oxidases (CcOs), such as aa3 from eukaryotic mitochondria, and some prokaryotes (often as caa3, where c represents a cytochrome c subunit), and QOs, such as bo3 of Escherichia coli [8][9][10]. HCOs of B and C families are present only in prokaryotes, with ba3 and cbb3 as respective representatives [9][11]. HCOs are highly efficient and specialized in pmf generation during the exothermic four-electron reduction of O2 because of the proton-pumping mechanism [12][13]. In contrast, bd QOs, found exclusively in prokaryotes to date, do not pump protons and are thus less efficient in energy conservation, but play an important role in mediating viability under various stress conditions [14][15].

Although HCOs of A, B, and C families are diverse in terms of subunit composition, electron donor, and heme type, they house a similar signature active site, the so-called binuclear center (BNC), where the reduction chemistry occurs [7]. Located in a subunit with 12 membrane-spanning helices, this BNC consists of two magnetically coupled redox-active metal centers, a high-spin heme (a3, o3, or b3), and a copper ion (CuB) [7][8][11][16]. In all HCOs, these two metal centers are in proximity, with the two metals (Fe and Cu) only ~5 Å apart [7][17]. During the oxygen reduction, the BNC experiences an oxidative-to-reductive phase transition involving several intermediate states [18].

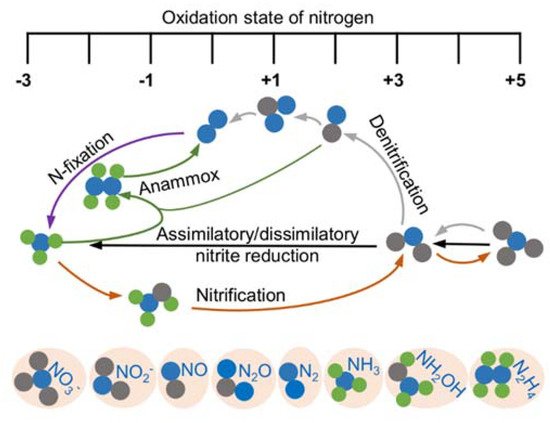

Nitrogen is essential to all life and is a constituent element of amino acids, proteins, and nucleic acids. After fixation, nitrogen as nitrogen gas (N2), the most abundant element in the atmosphere, can be converted to ammonium and a variety of nitrogen oxides, among which nitrite (NO2−) and nitric oxide (NO) are the most common and bioactive species [19][20] (Figure 1). Given that bacteria are able to catalyze all steps of the nitrogen cycle, they are crucial for the inter-conversion of different nitrogen oxides [21]. Both nitrite and NO are involved in diverse physiological processes in bacteria functioning as important cellular signaling molecules, substrates of metabolic enzymes, and inhibitory agents modulating protein activity [19][22]. Although a significant portion of phenotypic changes caused by nitrite are NO-independent, it is widely accepted that NO is the molecule largely underpinning the physiological influences; nitrite impacts the physiology of living organisms in part by serving as a biochemical circulating reservoir for NO [19]. Additionally, NO can be engaged in cellular physiological and pathological processes through a complex cross-talking with two other gasotransmitters, carbon monoxide (CO) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) [23][24][25][26][27]. Meanwhile, nitrite can be converted back to NO through the one-electron-oxidation of NO.

Figure 1. Redox cycle for nitrogen driven by prokaryotes. Shown are the major biological nitrogen transformation pathways, each of which are represented by lines in the same color, and the relative oxidation state at which they occur.

Given the particular importance of the inter-conversion of nitrite and NO, bacteria have evolved a variety of enzymes to catalyze the transformation of nitrite and NO, including NOR [19][28]. In addition, although the HCOs of all A, B, and C families differ from NOR in their metal ions within the BNCs, they are also profoundly implicated in the biology of nitrogen oxides. The direct reactions of HCOs with nitrite and NO, which have been known for a long time, provide a mechanistic understanding of the interplay between the enzymes and the two nitrogen oxides [29][30]. On one hand, it is well known that eukaryotic CcOs mediate the reduction of nitrite to NO under hypoxic conditions [31][32]. On the other hand, bacterial HCOs (ba3, caa3, bo3) of the A and B families are capable of catalyzing the reduction of NO to N2O, whereas C-family HCOs (cbb3) convert nitrite to N2O [19][33][34][35]. On the other hand, both nitrite and NO are bacteriostatic agents due to their ability to inhibit proteins, especially hemoproteins [36][37]. A great body of evidence has been accumulated showing that nitrite and NO react with purified HCOs and bd QOs in vitro and inhibit cell respiration in vivo [22][30][31][38][39][40][41][42]. While there are common reaction mechanisms involved in the inhibition by nitrite and NO, considerable discrepancies have been observed between their cellular targets identified to date [22]. Thus, the extent of the effective mechanisms elucidated by in vitro analyses is in living cells is still a matter of study.

2. Bacterial Terminal Oxidases for pmf Generation

Proton translocation across the membrane is of crucial importance for sustaining the cellular activity in all organisms. However, due to the polarity characteristics, protons are unable to pass through the phospholipid-bilayer membrane freely by diffusion like small non-polar molecules. Proton pumps are special and efficient hydrogen ion transporters that move protons across the membrane from the low-concentration side to the high-concentration side to form pmf, which is subsequently utilized to drive the production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the cell’s chemical energy currency, by ATP synthase [1][2][3].

In aerobic bacteria, transmembrane proton pumping is closely related to the oxidative phosphorylation process, especially with the terminal oxidases in the respiratory chain. The bacterial terminal oxidases, including HCOs of the A, B, and C families and bd QOs, catalyze the four-electron reduction of oxygen to water using quinol or cytochrome c as the electron donors. The main role of most HCOs in microbial metabolism is to conserve energy [43][44][45], and bd QOs are thought to contribute to nitrosative stress tolerance, hydrogen peroxide detoxification, or prevention of H2S toxicity, especially in pathogenic bacteria [42][46][47][48][49]. To date, a number of high-resolution structures of terminal oxidases from each group have been reported, which have greatly enhanced our understanding of the exact working mechanism of these enzymes.

2.1. HCOs

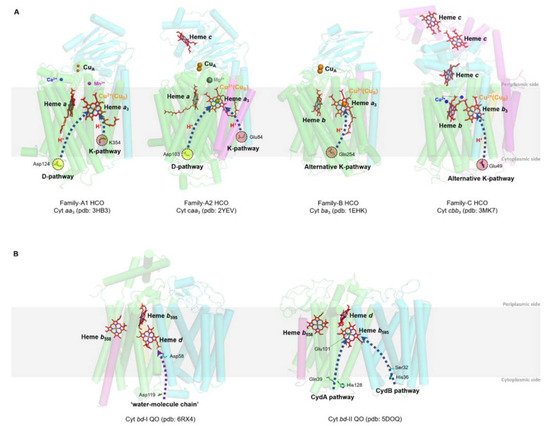

HCOs are the most extensively studied terminal oxidases. Despite the variety in the composition of the electron donor, polypeptide, and heme group type, all HCOs possess a conserved redox center composed of a low-spin heme and a heteronuclear heme-copper center (binuclear center, BNC) consisting of a high-spin heme and a copper (CuB) [44][50]. Based on the amino acid sequences and the proton-pumping pathways, members of the HCO superfamily are divided into three families as A, B, and C [51] (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Prosthetic group arrangements and proton pathways of typical bacterial HCOs (A) and bd QOs (B). (A) Representative structures of HCOs of A (divided into A1 and A2), B, and C subfamilies. Protein peptides, heme cofactors, and ions are shown as cartoons, sticks, and spheres, respectively. SUs I of families A and B, SU III of family A and CcoN of family C are colored in green; SUs II of families A and B, and CcoO of family C are colored in cyan; SU IV of family A, SU Iia of family B, and CcoO of family C are colored in magenta; the 30-mer peptide in family C HCO is colored in yellow. The blue dashed arrows indicate the proton pathways inside each HCO, with the amino acid residues at the entry point of each pathway marked with dashed cycles. (B) Structures of Cyt bd-I and bd-II QOs. Protein peptides and heme cofactors are shown as cartoons and sticks with subunits CydA and CydB colored in green and cyan, and CydX in bd-I QOs and CydS in bd-II QOs colored in magenta, respectively. The purple dashed arrow indicates the ‘water-molecule chain’ observed between residues Asp119 (subunit A) and Asp58 (subunit B) in bd-I QOs. The blue dashed arrows indicate two proposed proton pathways in bd-II QOs. Figures are prepared with PyMOL (Molecular Graphics System, LLC) https://www.pymol.org (accessed on 20 December 2021).

Bacterial A-family HCOs include aa3-type CcOs (aa3-HCO, in some cases caa3-HCO), which exhibit high structural relations to their mitochondrial counterparts, which contain only a-type hemes, and the bo3-type QOs (bo3-HCO) from E. coli (Figure 2A). Most often, A-family HCOs contain three subunits, named SU-I, II, and III. SU-I is highly conserved among all HCOs and typically composed of 12 transmembrane helices (TMHs), which hold the BNC [43]. SU-II contains a membrane-anchored cupredoxin domain functioning for harboring the mixed-valence di-nuclear copper (CuA) acting as the primary electron acceptor [43]. The divalent cations (Mg2+ or Mn2+) located at the interface between SU-I and SU-II and close to the high spin heme in HCOs of A and C families are not essential for proton pumping; however, their exact functions remain unclear [52][53]. SU-III is present in most bacterial A-family HCOs and possibly influences the oxygen reduction as well as the internal proton flow [43]. An additional subunit (SU-IV) is also identified in A-family HCOs, with its function a mystery yet [10][11][16].

B-family HCOs comprise similar subunit compositions but with low sequence homology to their A-family counterparts (Figure 2A). In contrast to the canonical composition of 12 TMHs in SU-I of A-family HCOs, SU-Is of B-family HCOs, as seen in CcOs from Thermus thermophilus and Aquifex aeolicus, possess 13 and 14 TMHs, respectively [54][55]. The SU-II of B-family HCOs resembles its A-family counterpart in that both contain a membrane-anchored cupredoxin domain; however, an additional subunit (SU-IIa) consisting of a single helix is identified in the former [55]. The His-Tyr cross-link in A-family HCOs, which functions to fix CuB in a certain configuration and distance from heme a3 at the BNC [56], is also conserved in B-family HCOs.

C-family HCOs are highly divergent from HCOs of the former two families in protein sequence (Figure 2A). To date, only cbb3-type CcOs are reported in this group [11]. The SU-I of C-family HCOs contains a His-Tyr cross-link as well, but with the two residues residing at two separate helices different from the situations in HCOs of A and B families. In addition, C-family HCOs lack the di-nuclear copper site (CuA) but utilize two auxiliary heme-binding subunits (CcoO and CcoP) to receive electrons from reduced cytochromes [11]. C-family HCO contains an extra subunit CcoQ, a small non-heme protein that is not required for catalytic activity but has a role in the assembly of the HCO complex [57].

The proton pumping in A-family HCOs is performed via two pathways, D-pathway and K-pathway, named accordingly by the conserved and functionally critical residues (Aspartate and Lysine, respectively) near the entry site of each pathway (Figure 2A). In order to pump protons, A-family HCOs utilize the internal ‘proton wires’ to transfer the electronic charges in a way similar to the Grotthuss mechanism [3][58]. Within the longer D-pathway, a series of acid residues and water molecules jointly form a consecutive chain through hydrogen bonds and connect the entrance aspartate to the gating residue close to the BNC [59]. Due to the crucial role of the water molecules, a water gating proton pumping mechanism was thereby proposed in D-pathway [60]. A-family HCOs could be further divided into two types as A1 and A2, based on the residue composition at the hydrophobic end of the D-pathway. Type A1 is featured with a conserved glutamate within the motif XGHPEV on helix VI. However, in type A2, this residue is replaced by consecutive tyrosine and serine in a YSHPXV motif. HCOs of both types A1 and A2 have a covalent bond between one of the CuB-coordinated histidines and a tyrosine on the same helix [61]. The D-pathway is responsible for transporting six protons, four of which are pumped to the positive side (P-side) of the membrane; the remaining two are donated to the active site for use in oxygen reduction [43]. By contrast, the shorter K-pathway typically consists of a few highly conserved polar residues and only qualifies to supply two protons to the catalytic site during the initial reduction of the BNC [59]. A conserved binding domain (carboxyl group) for amphipathic compounds adjacent to the entrance of the K-pathway tends to play a role in organizing the water chain, which supports proton uptake [9][62][63].

The canonical K- and D- pathways are absent in either B-family or C-family HCOs; instead, an alternative K-pathway analogous to that in A-family HCOs is exploited [11][54] (Figure 2A). This K-pathway in B-family HCOs consist of a series of conserved polar residues that form a proton channel. Most of these residues reside within SU-I, with an additional glutamate at the entry site on SU-II. C-family HCOs possess an alternative K-pathway structurally similar to that in B-family HCOs. Within the cbb3-HCOs from Pseudomonas stutzeri and Rhodobacter sphaeroides, the proton pathway propagates through a few polar residues with the terminal residue tyrosine cross-linked to one of the histidine ligated to CuB [11][64].

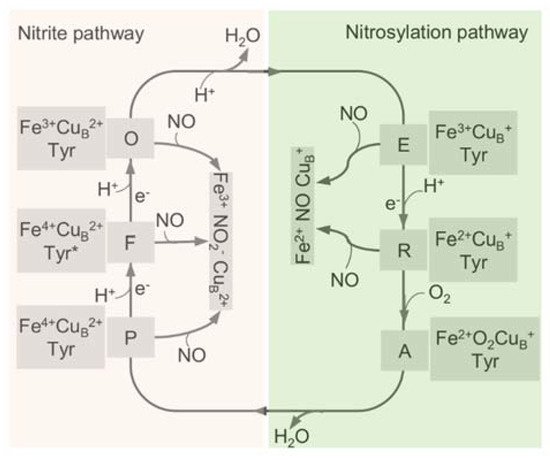

All HCOs are electrogenic proton pumps, and the internal and intramolecular electron transfer pathways for each HCO family have been extensively studied [43][65][66][67][68]. The catalytic cycle of A-family HCOs includes two phases, an oxidative phase and a reductive phase, involving several intermediate states of the active site, fully oxidized (O, Fe3+ CuB2+), single-electron reduced (E, Fe3+ CuB+ or Fe2+ CuB2+), and two-electron reduced (R, Fe2+ CuB+) (Figure 3) [18]. Upon O2 binding to R, a short-lived new complex A is formed, which delivers electrons rapidly to bound O2 for the cleavage of the dioxygen bond, forming intermediates P and F in sequence [69]. Both P and F are a ferryl derivative of (Fe4+ = O CuB2+), but the former carries Y244 in the radical form, whereas the latter has Y244 reduced and protonated [31][70][71][72]. Eventually, the fully oxidized state O is regenerated from F after receiving an additional electron from CuA/heme a. During the oxygen reduction, the first proton pumping event occurs during the P to F transition, and the reaction cycle completes when R is regenerated from E with two product water molecules released, and two protons pumped [73]. The source of the electron may be a tyrosine or tryptophan radical close to the active site; however, the exact identity of the amino acid, which provides this electron, is still under debate [43].

Figure 3. The catalytic cycle of HCO and the interplay with NO through the two pathways. The catalytic cycle of HCO is schematically reported with the indication of the redox and the oxygen ligation state of the BNC (heme a3-CuB active site). In the reductive phase, the oxidized species O is fully reduced to R by two single-electron donations via formation of the half-reduced intermediate E. In the oxidative phase, upon reaction with O2, R converts to P and F, and O is regenerated eventually through further electron transfer. The nitrite-bound derivative (Fe3+ CuB2+ NO2−) and the nitrosylated adduct (Fe2+ CuB+ NO) are generated by the reactions of these intermediates with NO. Tyr, CuB-interacting residue Y244, with an asterisk representing the radical form.

The proton-pumping loading sites in all HCOs are still controversial [74]. The histidines ligating the heme iron and CuB, as well as the A- and D- propionates of heme a3 at the catalytic center have been proposed as candidate proton loading sites [75]. A hydrophilic cavity above the hemes, housing divalent cations or water molecules at the interspace of SU-I and SU-II, is possibly the beginning of the water exit pathway [10][11][16].

2.2. bd QO

bd QO is a quinone-type terminal respiratory enzyme that distributes widely in bacteria and archaea. Unlike HCOs that have two hemes and a copper in the active sites, bd QOs accept electrons from quinones (ubiquinol or menaquinol) to reduce oxygen to water using three hemes (Figure 2B) [14][76]. A few isoforms of the bd QO family contain only b-type hemes, which are less sensitive to inhibition by cyanide [77]. Initially, bd QO was considered to consist of two subunits only, named CydA and CydB, encoded by a single operon [78]. However, a small single-transmembrane subunit (CydX or CydS) encoded by the third gene in the cyd operon is found to be not only functionally essential but also involved in the assembly of the enzyme complex in some bacteria in recent years [79][80][81]. Based on the structural differences of the quinol binding sites (Q-loop), bd QOs are subdivided into L-subfamily (long Q-loop) and S-subfamily (short Q-loop) [14][82].

bd QO lacks a counterpart proton-pumping mechanism as in HCOs; instead, they generate a pmf through the transmembrane charge separation and the coupled Q-cycle [83]. There are two potential proton pathways, CydA and CydB pathways, through which protons could pass from the cytoplasm to the high-spin heme site (b595) in bd QO from Geobacillus thermodenitrificans [15]. The proton transfer from heme b595 to the oxygen reduction site via heme d is possibly facilitated by water molecules or the heme propionates of heme b595 [15]. To date, no oxygen channels have been found in bd QOs, implying that oxygen molecules likely approach heme d laterally from the alkyl chain interface with the membrane [15].

3. Roles of HCOs in the Transformation of Nitrogen Oxides

In addition to carrying out O2 reduction, HCOs have been shown to be deeply implicated in the biotransformation of multiple nitrogen oxides. It is well recognized that mitochondrial aa3-HCO is capable of reducing NO2− to NO under hypoxic conditions [20][35]. This reduction, which involves only one electron, differs from the four-electron reduction of O2 to H2O and is not involved with proton pumping [35]. Unlike their eukaryotic counterparts, bacterial HCOs, including the caa3-HCO and ba3-HCO from T. thermophilus, cbb3-HCO from P. stutzeri, and bo3-HCO from E. coli, are able to catalyze the reduction of NO to N2O [36][84][85]. In addition, cbb3-HCO of P. stutzeri is also able to reduce NO2− to N2O directly [33].

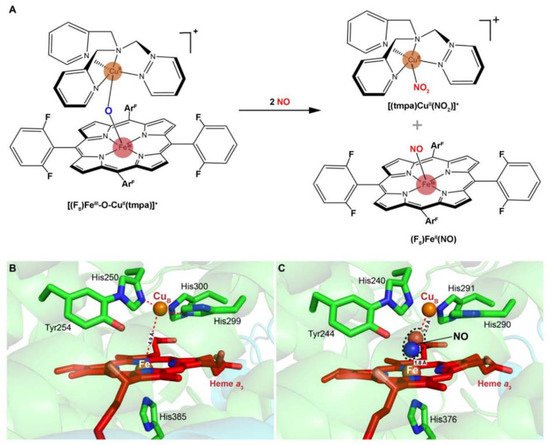

Despite having been known for a long time, the interactions of nitrite with mitochondrial aa3-HCO have not yet been addressed. Instead, the current understanding of the subject derives mainly from the reactions of nitrite with synthetic heme/copper assemblies [32][86][87] (Figure 4A). During catalytic turnover, the ferrous heme of the a3-CuB BNC functions as the electron donor, while the CuB center serves as a Lewis acid for the cleavage of the N-O bond of nitrite [32]. The overall reaction is a one-electron reduction of nitrite, during which an oxygen atom derived from the nitrite is transferred to the BNC, resulting in an oxo-bridge Fe3+-O-Cu2+ intermediate. Interestingly, this oxo-bridge Fe3+-O-Cu2+ could also oxidize NO back to nitrite. It is speculated that the inter-conversion of nitrite and NO has important implications in the modulation of cellular O2 balance [32][86][87]. When O2 is limited, nitrite interacts with the BNC for reduction, generating NO. This NO molecule can reversibly inhibit the oxygen reduction at the same site, leading to O2 accumulation. The reverse reaction is composed of the same steps traversed backward, and as a result, NO is converted back to nitrite for future use, and the enzyme is freed to catalyze the four-electron reduction of O2 to water. The overall reaction is regarded as an adaptive mechanism alleviating NO-mediated respiratory inhibition [88].

Figure 4. Scheme of a heme-copper assembly mediated oxidation of NO to nitrite and structures of ligand-absent and NO-binding BNCs of CcOs. (A) A μ-oxo heme-FeIII-O-CuII complex facilitates NO oxidation to nitrite, forming reduced heme and CuII-nitrito complexes. This scheme is modified from the figure in reference [26] with ChemDraw. (B) Spatial structure of the BNC of Cyt caa3 oxidase from T. thermophilus HB8. The copper atom (CuB) is coordinated by three histidine residues. The distance between CuB and heme-iron is less than 5 Å. (C) X-ray structure of the NO-bound CcO from bovine CcO. The distances between CuB and oxygen atom from NO, heme-Fe, and nitrogen atom from NO are 2.5 Å and 1.8 Å, respectively. Figures of B and C are prepared with PyMOL (Molecular Graphics System, LLC) https://www.pymol.org (accessed on 20 December 2021).

Multiple lines of evidence suggest that eukaryotic and bacterial HCOs have different reactivities to nitrogen species [89]. In contrast to eukaryotic mitochondrial HCOs, the bacterial counterparts react with nitrite and NO, producing N2O as the end product [33][34][89] (Figure 4B,C). Upon the addition of NO to oxidized ba3-HCO (O) of T. thermophilus, a six-coordinate heme Fe2+-NO species has been detected, suggesting that a hyponitrite (HONNO−) ion bound to the BNC in the E state (Fe3+ CuB+) is transiently formed [90]. Further investigations have demonstrated that the binding of two NO molecules to the BNC is accompanied by protonation of the heme a3-NO species and the electron transfer from CuB+, leading to the concomitant formation of the N-N bond. Eventually, N2O and H2O are released after additional H+ is added and the N-O bond is cleaved. This mechanism has been observed in reactions of NO with caa3-HCO, bcc-aa3 supercomplex (formed by cytochrome bcc and aa3-HCO in Mycobacterium tuberculosis), and bacterial NORs, suggesting a possibility that it is conserved in all enzymes of the HCO superfamily [91][92][93][94]. Despite this, the NO reductase activities of all HCOs tested so far are substantially lower than those observed with bacterial NORs, implying that their contribution to NO reduction is likely to be limited unless NORs are absent [85][95]. In addition, the ba3-HCO of T. thermophilus also interacts with nitrite to form a ferrous heme a3-nitro complex in the BNC, but NO or N2O is not produced above the detection limit, suggesting that this enzyme is likely to be susceptible to nitrite inhibition, as discussed below [89].

On the contrary, under reducing conditions, nitrite reacts with cbb3-HCO to form a six-coordinate ferrous heme b3-nitrosyl complex [33]. The binding of NO2− to heme b3 triggers electron transfer from the heme to the substrate, leading to its double protonation reduction to NO and release of a H2O molecule.

References

- Verstraeten, N.; Knapen, W.J.; Kint, C.I.; Liebens, V.; Van den Bergh, B.; Dewachter, L.; Michiels, J.E.; Fu, Q.; David, C.C.; Fierro, A.C.; et al. Obg and membrane depolarization are part of a microbial bet-hedging strategy that leads to antibiotic tolerance. Mol. Cell. 2015, 59, 9–21.

- Wang, M.; Chan, E.W.C.; Wan, Y.; Wong, M.H.; Chen, S. Active maintenance of proton motive force mediates starvation-induced bacterial antibiotic tolerance in Escherichia coli. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 1068.

- Kaila, V.R.I.; Wikström, M. Architecture of bacterial respiratory chains. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 319–330.

- Sousa, F.L.; Alves, R.J.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Pereira-Leal, J.B.; Teixeira, M.; Pereira, M.M. The superfamily of heme-copper oxygen reductases: Types and evolutionary considerations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2012, 1817, 629–637.

- Siletsky, S.A.; Borisov, V.B. Proton pumping and non-pumping terminal respiratory oxidases: Active sites intermediates of these molecular machines and their derivatives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10852.

- Hemp, J.; Gennis, R.B. Diversity of the heme–copper superfamily in archaea: Insights from genomics and structural modeling. In Bioenergetics: Energy Conservation and Conversion; Schäfer, G., Penefsky, H.S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 45, pp. 1–31.

- Wikström, M.; Krab, K.; Sharma, V. Oxygen activation and energy conservation by cytochrome c oxidase. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 2469–2490.

- Abramson, J.; Riistama, S.; Larsson, G.; Jasaitis, A.; Svensson-Ek, M.; Laakkonen, L.; Puustinen, A.; Iwata, S.; Wikström, M. The structure of the ubiquinol oxidase from Escherichia coli and its ubiquinone binding site. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2000, 7, 910–917.

- Liu, J.; Hiser, C.; Ferguson-Miller, S. Role of conformational change and K-path ligands in controlling cytochrome c oxidase activity. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2017, 45, 1087–1095.

- Lyons, J.A.; Aragão, D.; Slattery, O.; Pisliakov, A.V.; Soulimane, T.; Caffrey, M. Structural insights into electron transfer in caa3-type cytochrome oxidase. Nature 2012, 487, 514–518.

- Buschmann, S.; Warkentin, E.; Xie, H.; Langer, J.D.; Ermler, U.; Michel, H. The structure of cbb3 cytochrome oxidase provides insights into proton pumping. Science 2010, 329, 327–330.

- Faxén, K.; Gilderson, G.; Ädelroth, P.; Brzezinski, P. A mechanistic principle for proton pumping by cytochrome c oxidase. Nature 2005, 437, 286–289.

- Belevich, I.; Bloch, D.A.; Belevich, N.; Wikstrom, M.; Verkhovsky, M.I. Exploring the proton pump mechanism of cytochrome c oxidase in real time. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 2685–2690.

- Borisov, V.B.; Gennis, R.B.; Hemp, J.; Verkhovsky, M.I. The cytochrome bd respiratory oxygen reductases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2011, 1807, 1398–1413.

- Safarian, S.; Rajendran, C.; Müller, H.; Preu, J.; Langer, J.D.; Ovchinnikov, S.; Hirose, T.; Kusumoto, T.; Sakamoto, J.; Michel, H. Structure of a bd oxidase indicates similar mechanisms for membrane-integrated oxygen reductases. Science 2016, 352, 583–586.

- Iwata, S.; Ostermeier, C.; Ludwig, B.; Michel, H. Structure at 2.8 A resolution of cytochrome c oxidase from Paracoccus denitrificans. Nature 1995, 376, 660–669.

- Yoshikawa, S.; Shimada, A. Reaction Mechanism of cytochrome c oxidase. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 1936–1989.

- Sharma, V.; Karlin, K.D.; Wikström, M. Computational study of the activated O(H) state in the catalytic mechanism of cytochrome c oxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 16844–16849.

- Maia, L.B.; Moura, J.J. How biology handles nitrite. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 5273–5357.

- Canfield, D.E.; Glazer, A.N.; Falkowski, P.G. The evolution and future of earth’s nitrogen cycle. Science 2010, 330, 192–196.

- Kuypers, M.M.M.; Marchant, H.K.; Kartal, B. The microbial nitrogen-cycling network. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 263–276.

- Guo, K.L.; Gao, H.C. Physiological roles of nitrite and nitric oxide in bacteria: Similar consequences from distinct cell targets, protection, and sensing systems. Adv. Biol. 2021, 5, e2100773.

- Jeney, V.; Ramos, S.; Bergman, M.-L.; Bechmann, I.; Tischer, J.; Ferreira, A.; Oliveira-Marques, V.; Janse, C.J.; Rebelo, S.; Cardoso, S.; et al. Control of disease tolerance to malaria by nitric oxide and carbon monoxide. Cell Rep. 2014, 8, 126–136.

- Mancuso, C.; Navarra, P.; Preziosi, P. Roles of nitric oxide, carbon monoxide, and hydrogen sulfide in the regulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis. J. Neurochem. 2010, 113, 563–575.

- Mendes, S.S.; Miranda, V.; Saraiva, L.M. Hydrogen sulfide and carbon monoxide tolerance in bacteria. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 729.

- Moustafa, A. Changes in nitric oxide, carbon monoxide, hydrogen sulfide and male reproductive hormones in response to chronic restraint stress in rats. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 162, 353–366.

- Nowaczyk, A.; Kowalska, M.; Nowaczyk, J.; Grześk, G. Carbon monoxide and nitric oxide as examples of the youngest class of transmitters. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6029.

- Stern, A.M.; Zhu, J. An introduction to nitric oxide sensing and response in bacteria. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 87, 187–220.

- Brudvig, G.W.; Stevens, T.H.; Chan, S.I. Reactions of nitric-oxide with cytochrome-c oxidase. Biochemistry 1980, 19, 5275–5285.

- Sarti, P.; Forte, E.; Mastronicola, D.; Giuffrè, A.; Arese, M. Cytochrome c oxidase and nitric oxide in action: Molecular mechanisms and pathophysiological implications. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2012, 1817, 610–619.

- Sarti, P.; Giuffrè, A.; Barone, M.C.; Forte, E.; Mastronicola, D.; Brunori, M. Nitric oxide and cytochrome oxidase: Reaction mechanisms from the enzyme to the cell. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2003, 34, 509–520.

- Hematian, S.; Siegler, M.A.; Karlin, K.D. Heme/Copper assembly mediated nitrite and nitric oxide interconversion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 18912–18915.

- Loullis, A.; Pinakoulaki, E. Probing the nitrite and nitric oxide reductase activity of cbb3 oxidase: Resonance Raman detection of a six-coordinate ferrous heme–nitrosyl species in the binuclear b3/CuB center. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 17398–17401.

- Giuffre, A.; Stubauer, G.; Sarti, P.; Brunori, M.; Zumft, W.G.; Buse, G.; Soulimane, T. The heme-copper oxidases of Thermus thermophilus catalyze the reduction of nitric oxide: Evolutionary implications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 14718–14723.

- Castello, P.R.; David, P.S.; McClure, T.; Crook, Z.; Poyton, R.O. Mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase produces nitric oxide under hypoxic conditions: Implications for oxygen sensing and hypoxic signaling in eukaryotes. Cell Metab. 2006, 3, 277–287.

- Ford, P.C. Reactions of NO and nitrite with heme models and proteins. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 6226–6239.

- Ford, P.C.; Miranda, K.M. The solution chemistry of nitric oxide and other reactive nitrogen species. Nitric Oxide 2020, 103, 31–46.

- Yoshikawa, S.; Orii, Y. Inhibition mechanism of cytochrome-oxidase reaction 2 classifications of inhibitors based on their modes of action. J. Biochem. 1972, 71, 859–872.

- Rowe, J.J.; Yarbrough, J.M.; Rake, J.B.; Eagon, R.G. Nitrite inhibition of aerobic-bacteria. Curr. Microbiol. 1979, 2, 51–54.

- Stevens, T.H.; Brudvig, G.W.; Bocian, D.F.; Chan, S.I. Structure of cytochrome a3-CuA3 couple in cytochrome c oxidase as revealed by nitric oxide binding studies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1979, 76, 3320–3324.

- Hori, H.; Tsubaki, M.; Mogi, T.; Anraku, Y. EPR study of NO complexes of bd-type ubiquinol oxidase from Escherichia coli: The proximal axial ligand of heme D is a nitrogenous amino acid residue. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 9254–9258.

- Mason, M.G.; Shepherd, M.; Nicholls, P.; Dobbin, P.S.; Dodsworth, K.S.; Poole, R.K.; Cooper, C.E. Cytochrome bd confers nitric oxide resistance to Escherichia coli. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009, 5, 94–96.

- Lyons, J.A.; Hilbers, F.; Caffrey, M. Structure and function of bacterial cytochrome c oxidases. In Cytochrome Complexes: Evolution, Structures, Energy Transduction, and Signaling; Cramer, W.A., Kallas, T., Eds.; Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 41, pp. 307–329.

- Wikström, M.; Verkhovsky, M.I. Mechanism and energetics of proton translocation by the respiratory heme-copper oxidases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2007, 1767, 1200–1214.

- Lu, Y.; Sigman, J.A.; Kim, H.K.; Zhao, X.; Carey, J.R. The role of copper and protons in heme-copper oxidases: Kinetic study of an engineered heme-copper center in myoglobin. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2003, 96, 183.

- Giuffrè, A.; Borisov, V.B.; Arese, M.; Sarti, P.; Forte, E. Cytochrome bd oxidase and bacterial tolerance to oxidative and nitrosative stress. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2014, 1837, 1178–1187.

- Borisov, V.B.; Forte, E. Terminal oxidase cytochrome bd protects bacteria against hydrogen sulfide toxicity. Biochemistry 2021, 86, 22–32.

- Borisov, V.B.; Siletsky, S.A.; Nastasi, M.R.; Forte, E. ROS defense systems and terminal oxidases in bacteria. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 839.

- Korshunov, S.; Imlay, K.R.; Imlay, J.A. The cytochrome bd oxidase of Escherichia coli prevents respiratory inhibition by endogenous and exogenous hydrogen sulfide. Mol. Microbiol. 2016, 101, 62–77.

- Yoshikawa, S.; Muramoto, K.; Shinzawa-Itoh, K. Proton-pumping mechanism of cytochrome c oxidase. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2011, 40, 205–223.

- Pereira, M.M.; Santana, M.; Teixeira, M. A novel scenario for the evolution of haem-copper oxygen reductases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2001, 1505, 185–208.

- Florens, L.; Schmidt, B.; McCracken, J.; Ferguson-Miller, S. Fast deuterium access to the buried magnesium/manganese site in cytochrome c oxidase. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 7491–7497.

- Mills, D.A.; Florens, L.; Hiser, C.; Qian, J.; Ferguson-Miller, S. Where is ′outside′ in cytochrome c oxidase and how and when do protons get there? Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2000, 1458, 180–187.

- Soulimane, T.; Buse, G.; Bourenkov, G.P.; Bartunik, H.D.; Huber, R.; Than, M.E. Structure and mechanism of the aberrant ba(3)-cytochrome c oxidase from thermus thermophilus. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 1766–1776.

- Zhu, G.; Zeng, H.; Zhang, S.; Juli, J.; Tai, L.; Zhang, D.; Pang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lam, S.M.; Zhu, Y.; et al. The unusual homodimer of a heme-copper terminal oxidase allows itself to utilize two electron donors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 13323–13330.

- Pinakoulaki, E.; Stavrakis, S.; Urbani, A.; Varotsis, C. Resonance Raman Detection of a Ferrous Five-Coordinate Nitrosylheme b3 Complex in Cytochrome cbb3 Oxidase from Pseudomonas stutzeri. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 9378–9379.

- Kohlstaedt, M.; Buschmann, S.; Langer, J.D.; Xie, H.; Michel, H. Subunit CcoQ is involved in the assembly of the cbb(3)-type cytochrome c oxidases from Pseudomonas stutzeri ZoBell but not required for their activity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2017, 1858, 231–238.

- Agmon, N. The grotthuss mechanism. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1995, 244, 456–462.

- Harrenga, A.; Michel, H. The cytochrome c oxidase from Paracoccus denitrificans does not change the metal center ligation upon reduction. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 33296–33299.

- Kim, Y.C.; Wikström, M.; Hummer, G. Kinetic gating of the proton pump in cytochrome c oxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 13707–13712.

- Pereira, M.M.; Santana, M.; Soares, C.M.; Mendes, J.; Carita, J.N.; Fernandes, A.S.; Saraste, M.; Carrondo, M.A.; Teixeira, M. The caa3 terminal oxidase of the thermohalophilic bacterium Rhodothermus marinus: A HiPIP:oxygen oxidoreductase lacking the key glutamate of the D-channel. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 1999, 1413, 1–13.

- Qin, L.; Mills, D.A.; Buhrow, L.; Hiser, C.; Ferguson-Miller, S. A conserved steroid binding site in cytochrome c oxidase. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 9931–9933.

- Hiser, C.; Buhrow, L.; Liu, J.; Kuhn, L.; Ferguson-Miller, S. A conserved amphipathic ligand binding region influences k-path-dependent activity of cytochrome c oxidase. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 1385–1396.

- Rauhamäki, V.; Baumann, M.; Soliymani, R.; Puustinen, A.; Wikström, M. Identification of a histidine-tyrosine cross-link in the active site of the cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 16135–16140.

- Drosou, V.; Malatesta, F.; Ludwig, B. Mutations in the docking site for cytochrome c on the Paracoccus heme aa3 oxidase. Electron entry and kinetic phases of the reaction. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002, 269, 2980–2988.

- Muresanu, L.; Pristovsek, P.; Löhr, F.; Maneg, O.; Mukrasch, M.D.; Rüterjans, H.; Ludwig, B.; Lücke, C. The electron transfer complex between cytochrome c552 and the CuA domain of the Thermus thermophilus ba3 oxidase. A combined NMR and computational approach. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 14503–14513.

- Gray, H.B. Electron flow through metalloproteins. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2001, 86, 1.

- Maneg, O.; Malatesta, F.; Ludwig, B.; Drosou, V. Interaction of cytochrome c with cytochrome oxidase: Two different docking scenarios. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2004, 1655, 274–281.

- Chance, B.; Saronio, C.; Leigh, J.S., Jr. Functional intermediates in the reaction of membrane-bound cytochrome oxidase with oxygen. J. Biol. Chem. 1975, 250, 9226–9237.

- Fabian, M.; Wong, W.W.; Gennis, R.B.; Palmer, G. Mass spectrometric determination of dioxygen bond splitting in the "peroxy" intermediate of cytochrome c oxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 13114–13117.

- Giuffrè, A.; Barone, M.C.; Mastronicola, D.; D′Itri, E.; Sarti, P.; Brunori, M. Reaction of nitric oxide with the turnover intermediates of cytochrome c oxidase: Reaction pathway and functional effects. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 15446–15453.

- Blomberg, M.R.A. Activation of O(2) and NO in heme-copper oxidases—Mechanistic insights from computational modelling. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 7301–7330.

- Michel, H. Cytochrome c oxidase: Catalytic cycle and mechanisms of proton pumping—A discussion. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 15129–15140.

- Kaila, V.R.; Sharma, V.; Wikström, M. The identity of the transient proton loading site of the proton-pumping mechanism of cytochrome c oxidase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2011, 1807, 80–84.

- Kaila, V.R.; Johansson, M.P.; Sundholm, D.; Laakkonen, L.; Wiström, M. The chemistry of the CuB site in cytochrome c oxidase and the importance of its unique His-Tyr bond. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2009, 1787, 221–233.

- Murali, R.; Gennis, R.B.; Hemp, J. Evolution of the cytochrome bd oxygen reductase superfamily and the function of CydAA′ in Archaea. ISME J. 2021, 15, 3534–3548.

- Azarkina, N.; Siletsky, S.; Borisov, V.; von Wachenfeldt, C.; Hederstedt, L.; Konstantinov, A.A. A cytochrome bb′-type quinol oxidase in Bacillus subtilis strain 168. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 32810–32817.

- Williams, C.; McColl, K.E. Review article: Proton pump inhibitors and bacterial overgrowth. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2006, 23, 3–10.

- Hoeser, J.; Hong, S.; Gehmann, G.; Gennis, R.B.; Friedrich, T. Subunit CydX of Escherichia coli cytochrome bd ubiquinol oxidase is essential for assembly and stability of the di-heme active site. FEBS Lett. 2014, 588, 1537–1541.

- Chen, H.; Luo, Q.; Yin, J.; Gao, T.; Gao, H. Evidence for the requirement of CydX in function but not assembly of the cytochrome bd oxidase in Shewanella oneidensis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2015, 1850, 318–328.

- Thesseling, A.; Rasmussen, T.; Burschel, S.; Wohlwend, D.; Kaegi, J.; Mueller, R.; Boettcher, B.; Friedrich, T. Homologous bd oxidases share the same architecture but differ in mechanism. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5138.

- Osborne, J.P.; Gennis, R.B. Sequence analysis of cytochrome bd oxidase suggests a revised topology for subunit I. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 1999, 1410, 32–50.

- Bertsova, Y.V.; Bogachev, A.V.; Skulachev, V.P. Generation of protonic potential by the bd-type quinol oxidase of Azotobacter vinelandii. FEBS Lett. 1997, 414, 369–372.

- Forte, E.; Urbani, A.; Saraste, M.; Sarti, P.; Brunori, M.; Giuffrè, A. The cytochrome cbb3 from Pseudomonas stutzeri displays nitric oxide reductase activity. Eur. J. Biochem. 2001, 268, 6486–6491.

- Butler, C.S.; Forte, E.; Maria Scandurra, F.; Arese, M.; Giuffré, A.; Greenwood, C.; Sarti, P. Cytochrome bo3 from Escherichia coli: The binding and turnover of nitric oxide. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002, 296, 1272–1278.

- Hematian, S.; Garcia-Bosch, I.; Karlin, K.D. Synthetic heme/copper assemblies: Toward an understanding of cytochrome c oxidase interactions with dioxygen and nitrogen oxides. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 2462–2474.

- Hematian, S.; Kenkel, I.; Shubina, T.E.; Dürr, M.; Liu, J.J.; Siegler, M.A.; Ivanovic-Burmazovic, I.; Karlin, K.D. Nitrogen oxide atom-transfer redox chemistry; mechanism of NO(g) to nitrite conversion utilizing μ-oxo Heme-FeIII–O–CuII(L) constructs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 6602–6615.

- Torres, J.; Cooper, C.E.; Wilson, M.T. A common mechanism for the interaction of nitric oxide with the oxidized binuclear centre and oxygen intermediates of cytochromec oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 8756–8766.

- Loullis, A.; Noor, M.R.; Soulimane, T.; Pinakoulaki, E. The structure of a ferrous heme-nitro species in the binuclear heme a3/CuB center of ba3-cytochrome c oxidase as determined by resonance Raman spectroscopy. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 286–289.

- Pinakoulaki, E.; Ohta, T.; Soulimane, T.; Kitagawa, T.; Varotsis, C. Detection of the His-Heme Fe2+−NO species in the reduction of NO to N2O by ba3-oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 15161–15167.

- Daskalakis, V.; Ohta, T.; Kitagawa, T.; Varotsis, C. Structure and properties of the catalytic site of nitric oxide reductase at ambient temperature. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 2015, 1847, 1240–1244.

- Ohta, T.; Soulimane, T.; Kitagawa, T.; Varotsis, C. Nitric oxide activation by caa3 oxidoreductase from Thermus thermophilus. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 10894–10898.

- Varotsis, C.; Ohta, T.; Kitagawa, T.; Soulimane, T.; Pinakoulaki, E. The structure of the hyponitrite species in a heme Fe-Cu binuclear center. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 2210–2214.

- Forte, E.; Giuffrè, A.; Huang, L.-s.; Berry, E.A.; Borisov, V.B. Nitric oxide does not inhibit but is metabolized by the cytochrome bcc-aa3 supercomplex. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8521.

- Girsch, P.; de Vries, S. Purification and initial kinetic and spectroscopic characterization of NO reductase from Paracoccus denitrificans. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 1997, 1318, 202–216.

More

Information

Subjects:

Biochemistry & Molecular Biology; Microbiology

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.2K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

26 Jan 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No