3. 3D Tissue Spheroids Comprised of ECs and Perivascular Cells

Tissue spheroids are cell aggregates that are formed in non-adhesive conditions, preventing the attachment of cells to the bottom of a culture flask or other substrates that are used to maintain the 2D cultures. They can be generated by various methods, including spontaneous spheroid formation in the ultra-low binding plates, spontaneous in the ultra-low binding plates containing hydrogels, “hanging drop” technique, spheroid formation in suspension cultures in bioreactors, or using magnetic levitation

[33]. Here, we shall concentrate on the first two, since they are up-to-date, informative, and cost-effective.

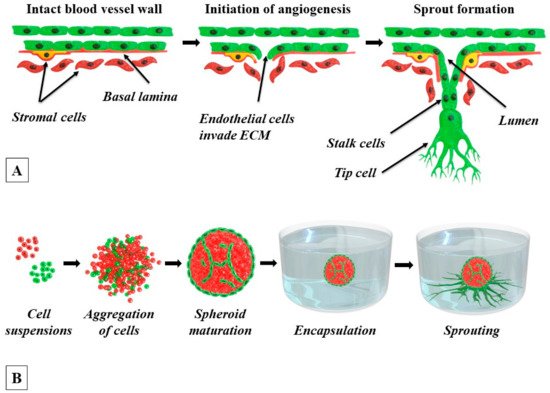

The self-assembly of spheroids in a cell suspension is presented in

Figure 1B. In the absence of an adhesive substrate, the cells begin to aggregate with neighboring cells by cadherins, a subclass of cell adhesion molecules (CAMs)

[33]. The presence in the microenvironment of fibrillar proteins that are rich in the RGD, PHSRN, GFOGER, RGDWXE, and other motifs in their primary structure, such as the ECM proteins fibronectin, laminin, vitronectin, fibrin, and collagen, facilitates spheroid initiation and further outbound migration of cells from the formed spheroids

[33][34][35]. Some of these proteins provide better results after partial denaturation. The integrin-fibrillary protein interactions contribute to the physical convergence of the cells to form compact aggregates and induce the upregulation of the expression of cadherins and their assembling to form clusters on the surface of cells. Next, the cadherin-cadherin interactions between neighboring cells tighten the cell-cell connections further and promote additional spheroid compaction. The tissue spheroids sharing many common biological features with a number of normal or diseased tissues, such as vascularized tumors, blood-brain barrier, and cardiac tissue, were produced

[36][37][38]. The ability to co-culture two or more cell types makes 3D tissue spheroids a promising tool to model heterotypic cell-cell interactions and brings this 3D system to the cutting edge of tissue engineering and drug screening

[33][34][39][40].

Since Korff and Augustin introduced the EC-spheroid model in 1998

[41] and later a collagen-gel-based 3D angiogenesis model that was based on EC-spheroids that are embedded in a collagen gel

[15], much attention has been directed to the application of tissue spheroids in angiogenesis modeling. In vivo, the growth of new vessels is regulated by the perivascular niche and involves the activation and recruitment of perivascular cells and ECM modulation. Accordingly, realistic angiogenesis models should include perivascular cells and ECM elements. In monoculture, the ECs do not tend to form 3D structures, probably because in their natural environment in blood vessels they are organized into one-cell-thick tubes. Therefore, the protocols of EC monoculture spheroids formation include the addition of methylcellulose as a suspending agent that does not allow spheroids to sediment

[42][43]. In contrast to ECs, stromal cells easily self-organize into 3D multicellular aggregates, and, accordingly, the presence of perivascular stromal cells improves the spheroid formation process

[44].

Importantly, it was shown that ECs that are co-cultured with adhesive perivascular cells such as VSMCs, pericytes, fibroblasts, MSCs, and osteoblasts in heterotypic tissue spheroids, demonstrate a very specific localization pattern where they form a monolayer at the spheroid surface and a primitive 3D capillary bed-like network within the spheroid core

[45][46][47] (

Figure 1B and

Figure 2 show our own unpublished data

[48]). The mechanism of such ECs spatial distribution is not fully understood and needs further investigation. According to Steinberg’s differential adhesion hypothesis, the aggregation of two and more different cell types in tissue spheroids promotes specific spatial cell localization patterns (a phenomenon called “cell sorting”) that affects the spheroid properties

[49][50]. Different adhesive cell types demonstrate different cell sorting behaviors, and the mechanisms of cell sorting patterns look controversial

[50][51]. With regard to the endothelial-perivascular spheroids, it is known that the formation of a vascular network within the tissue spheroids depends primarily on the diameter of the spheroid determining the presence of a necrotic zone. Tissue spheroids have diffusion limitations of 150–200 µm that are applicable to many molecules, including O

2 [33]. Thus, tissue spheroids with a diameter above 500 µm always have a necrotic core in the center that is surrounded by a quiescent viable cell zone and a peripheral layer of proliferating cells

[33]. Eckermann et al.

[45] clearly demonstrated that the formation of a necrotic zone in the ECs-fibroblasts mixed spheroids exceeding 650 µm in diameter leads to massive cell death due to apoptosis and prevents the formation of ECs vascular network. In the majority of studies, the ECs/perivascular cells ratio of 1:1 is considered as an optimal ratio

[52][53][54], however in a rather early study it was shown that tissue spheroids that contained up to 10 % of ECs developed dense endothelial networks, while the use of higher percentages of ECs led to less elongated structures that were similar to cell clumps

[45]. Most probably, the optimum ratio should be determined in each particular case. Indeed, good quality spheroids could be framed using ECs/MSCs ratios between 1/3 and 5/1

[55][56][57]. As part of our own work, we have successfully generated heterotypic spheroids, each containing about 1000 cells and consisting of HUVECs and umbilical cord MSCs at a 1:1 ratio (unpublished data)

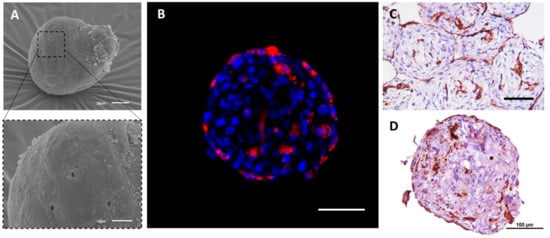

[48]. The spheroids were characterized by means of scanning electron microscopy (

Figure 2A) and confocal microscopy (

Figure 2B). The distinctive distribution of both cell types within the spheroids has been observed (

Figure 2B,D). Amongst the broad functional testing of the obtained spheroids, their capacity to fuse has been demonstrated indicating good viability and general condition of the cells comprising them (

Figure 2C).

Figure 2. The structure and internal organization of heterotypic tissue spheroids that are assembled of HUVECs and human umbilical cord MSCs (UCMSCs). The formation of the spheroids: the suspension of cells (100 µL per well, 1000 cells per spheroid, 1:1 ratio) was added to the non-adhesive U-bottom 96-well plate (Corning, Corning, NY, USA). After 72 h, the spheroids were collected and studied using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), immunofluorescence (IF), and immunohistochemistry (IHC). (A) SEM of the heterotypic HUVEC-UCMSC spheroids at day three in culture. The scale bars correspond to 20 μm (top) and 10 μm (bottom). (B) IF study of the formation of the 3D inner endothelial structures inside HUVEC-UCMSC spheroids. HUVECs were labeled with PKH26 (red, Sigma, USA) prior to tissue spheroids formation. The mixed tissue spheroids were incubated with DAPI (1:1000, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) to counterstain cell nuclei (blue). The scale bar corresponds to 100 µm. (C,D) IHC staining of spheroids for CD31, a marker of HUVECs. Prior to histological slides preparation, 20 spheroids were collected and placed into one well of the non-adhesive U-bottom plate for two hours to ensure their fusion. The entrapped in molten agarose tissue spheroids were fixed in 10% buffered formalin (pH 7.4) for 24 h and embedded in paraffin (Biovitrum, St Petersburg, Russia). 5 µm thick sections were cut with Microtome HMS 740 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and mounted on poly-L-lysine coated glass slides. Primary polyclonal rabbit antibodies to human CD31 (PECAM) were used in 1:100 dilutions. The nuclei were counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin. Finally, the sections were dehydrated and enclosed in Bio-Mount (Bio Optica, Milano SPA, Italy). The scale bar corresponds to 100 µm.

Marshall et al.

[52] identified regulatory pathways that were involved in the spatial organization and functioning of heterotypic spheroids incorporating ECs and MSCs. In this study, the cells were pre-treated with the inhibitors and antagonists of key signaling pathways that were associated with EC migration and behavior, including the inhibitors of integrin-linked kinase, Notch pathway, and antagonists of PDGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), and fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR). Blocking of the integrin-linked kinase and PDGFR resulted in the formation of a more prominent EC network. The inhibition of the Notch signaling promoted shifting of the EC capillary-like structures to the periphery of spheroids, while the blocking of FGFR led to a disruption of the EC network formation and induced ECs aggregation within the center of the spheroid. The blocking of EGFR appeared to have no effect on EC network formation. These data demonstrate that ECs behavior in heterotypic spheroids in the presence of MSCs is influenced by a number of endogenous signaling systems, especially by the PDGF signaling pathway.

Several studies demonstrated the presence of lumens within some of the endothelial cords constituting the internal endothelial network within the heterotypic spheroids

[44][47]. It was shown that lumen formation in 3D spheroids is regulated by the mechanisms similar to those active in vivo. Sonic Hedgehog morphogen, being expressed in the process of endothelial tube formation during neovascularization after trauma

[58] and during wound healing

[59], also promotes lumen formation in tissue spheroids. It regulates the expression of angiogenic genes, in particular encoding for cytoskeleton proteins and proteins that are related to pseudopodia-associated cell migration that is crucial for adequate lumen formation and guidance of the tip cells

[47].

Perivascular and other stromal cells not only assist 3D endothelial network formation, but influence ECs viability and are engaged in ECM deposition. The presence of perivascular cells in heterotypic spheroids prevents ECs apoptosis and prolongs their lifespan during long-term culture in comparison to EC monoculture spheroids

[44]. Spheroids comprising of VSMCs or fibroblasts improve ECs viability under low serum conditions (2% fetal calf serum, FCS)

[16][60]. The transmission electronic microscopy showed that ECs in co-culture spheroids established more junctional complexes than in EC monoculture spheroids, and also some microvesicular bodies and extracellular vesicles were detected, suggesting functional cell-cell interactions

[16][60][61]. In 10 day-old spheroids, some ECs formed intracellular vacuoles and EC cords that contained lumens and basement membrane, indicating the self-assembly of real microvessels

[44]. It was also shown that the endothelial expression of PDGF was completely down-regulated in mixed EC-VSMC spheroids over time

[16], while the OEC-MSC spheroids accumulated vast amounts of fibronectin and collagen type IV-proteins that are specific for the basal membrane of capillaries

[61]. In EC-osteoblast co-culture, spheroids osteocalcin and alkaline phosphatase as well as VEGF were detected suggesting the tissue-specific origin of the perivascular cells, in this particular case probably originating from osteoblasts

[62]. It was also shown that ECs that were cocultured with VSMCs in mixed spheroids expressed N-cadherin that is known to be a marker of EC-pericyte communication during angiogenesis

[63][64].

4. 3D Spheroid Sprouting Model

The 3D spheroid sprouting assay was first acknowledged in 1998 as an in vitro angiogenesis model that was based on 3D ECs monoculture spheroid that was embedded in collagen or fibrin to induce sprouting, i.e., the formation of tubular capillary structures

[41]. Later, this assay was modified and switched to the use of heterotypic EC–perivascular cell spheroids to better mimic the microenvironment of the vascular niche

[65][54]. This latter version allowed modeling of both endothelial-perivascular cell interactions during the formation of sprouts and the role of ECM in this process. The process of tissue spheroids preparation was described in

Section 4 in this paper. The procedure of the application of the tissue spheroid technology to angiogenesis modeling and studies of the influence of various factors on this process are presented below. The combination of both is schematically represented in

Figure 1B.

Angiogenesis modeling starts with the entrapment of tissue spheroids in hydrogels containing ECM proteins (mostly, collagen type I

[66][67][68][69] or fibrin

[70][61], or, less often, Matrigel

[44]). After one to two days of culture, several parameters of sprouts are analyzed. To describe the sprouting process quantitatively, the cumulative sprout length parameter (CSL), defined as total distance from the center of the spheroid to the tip of each sprout of the spheroid (sometimes of the three or five longest sprouts), is commonly used

[64]. In addition to CSL, characteristics such as average sprout length per spheroid, average number of sprouts per spheroid, sprouting area, number of branching points, and mean sprout diameter are also applied to analyze the sprouting process and compare the experimental groups. Usually a combination of parameters is used. To evaluate the endothelial-stromal cell interactions during sprouting, the EC and mural cell sprout coverage is analyzed as a percentage of total sprout length. With regard to the software, the most popular as of 18 November, 2021 was the free ImageJ image processing program (

https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ (accessed on 18 November 2021)). In addition to basic software functions, plugin Angiogenesis Analyzer designed for the fibrin bead assay

[71] can be installed.

Despite the fact that a 3D spheroid sprouting model has been applied for more than 20 years, it is still unclear what should be defined as “sprouts” in case of in vitro modeling of angiogenesis. In the literature, authors describe sprouting very differently, from “radial outgrowth of cells”

[62], i.e., migration, to “columns of migrating cells”

[54], “multiple contiguous cords”

[54], and ‘linear alignment of cells”

[60] indicating the formation of specific patterns of cell migration and organization. It raises an important question—should any migration of ECs be considered as sprouting? It is worth mentioning that stromal cells also migrate out from the stromal spheroids and form structures with sprout-like morphology

[43][53][62][72]. This phenomenon can be attributed to the pro-migratory properties of collagen and fibrin which maintain cellular adhesion and migration without additional stimulation

[73]. This fact indicates that the outbound growth of the cells itself cannot be a measure of proangiogenic effect. However, it likely affects the outgrowth of EC sprouts. The migration of cells is an important step of sprouting, but per se, it cannot ensure the formation of mature organized tubular structures. 3D spheroids-based sprouting angiogenesis is a complex dynamic process which can be described as a type of collective endothelial and perivascular cells migration, following or accompanying the formation of ordered lumenalized structures with smooth and compact cell morphology inside the spheroids. This is schematically presented in

Figure 1B.

Figure 2 gives a real-life example of the formation of microvessel-like structures within spheroids, while

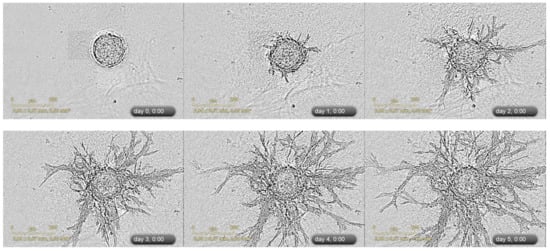

Figure 3 illustrates the outbound angiogenic sprouting.

Figure 3. An example of 3D spheroid sprouting assay. Representative images of sprouting of heterotypic HUVEC-UCMSC 3D spheroids were acquired with IncuCyte Zoom imaging system (Sartorius, Bohemia, NY, USA). Corresponding video file S1 is available in the

Supplementary Materials. The suspension of cells containing HUVECs and umbilical cord MSCs (cell ratio 1:1) was added (100 µL per well) to the non-adhesive U-bottom 96-well plate (Corning, Waltham, MA, USA). After 72 h, the spheroids were collected and embedded in fibrin gel (4 mg/mL) that was supplemented with 20% platelet lysate (PL) and maintained at +37 °C in CO

2-incubator for 5 days. Phase-contrast microscopy (the scale bar corresponds to 200 µm).

Despite data interpretation challenges, 3D heterogeneous spheroid sprouting assay is being actively applied to evaluate the effect of mural cells on ECs behavior. To analyze the distribution of cells and sprouts in hydrogels, ECs only, or both ECs and mural cells can be labeled with cell tracker dyes (for instance, PKH26 and PKH67) or transfected with genetic constructs expressing fluorescent proteins (GFP or RFP) to perform live imaging. Though it has been proven that the presence of pericytes is crucial for the formation of mature, stabilized capillaries, data concerning the participation of perivascular cells in sprouting angiogenesis and the mechanisms thereof are controversial. Thus, the ECs coculture with VSMCs or fibroblasts decrease ECs’ sprouting

[16][60] and this effect is mediated by direct cell-cell interactions, while paracrine regulation itself is not sufficient to drive this process

[60]. Comparing the effect of MSCs, fibroblasts, and placental pericytes, it was reported that pericytes promote the formation of sprouts with smooth and compact morphology and follow these structures while MSCs and fibroblasts migrate from ECs and stay segregated from sprouts

[69].

Interestingly, it was recently shown that the regulation of ECs sprouting activity by pericytes has temporal and spatial constituents

[54]. Pericytes from human placenta initially induce paracrine stimulation of sprouting via the production of HGF. HUVECs over the first eight hours sprout independently of pericytes, and after that the pericytes are recruited to the newly formed sprouts. PDGFR-β signaling promotes the recruitment of pericytes as the knock-down of PDGFR-β in pericytes by small interfering RNA (siRNA) leads to a decrease in EC-pericyte association and an increase in ECs sprouting. By 24 h, essentially all ECs sprouts are followed by pericytes and a further increase of the CSL terminates. In contrast, ECs monoculture spheroids continue to increase both the CSL and the number of sprouts. The direct EC-pericyte contact leads to the inhibition of the stimulatory effect on the ECs sprouting. In the light of the above, the influence of perivascular cells should be analyzed over time.

In addition to ECs sprouting and migration regulation, perivascular cells (such as fibroblasts and VSMCs) improve ECs viability

[16][60]. It was shown that EC monoculture spheroids demonstrated migration of cells into collagen up to 24–48 h

[43], but later their viability dramatically decreased and they, therefore, could not form vessel-like structures in a sustained way

[54][68]. The results of several studies demonstrated an increased viability of ECs that were cocultured with perivascular cells within spheroids in collagen for up to four to seven days

[66][64][67][68]. The perivascular cells can also modulate ECs sensitiveness to proangiogenic growth factors such as VEGF and basic FGF. ECs migrate out of the monoculture spheroids in response to VEGF in a dose-dependent manner

[16][43]. However, prolonged co-culture of some ECs with perivascular cells (VSMCs, pericytes, bone marrow-derived MSCs, or osteoblasts) leads to non-responsiveness to VEGF and bFGF stimulation

[16][42][54][62]. At the same time, it was shown that sprouting of liver sinusoidal ECs in co-culture spheroids increases in response to VEGF and bFGF

[64]. Thus, ECs might have different sensitiveness to bFGF and VEGF depending on their tissue origin.