1. Accountability in Social Economy

Several studies reveal that stakeholders are increasingly demanding higher levels of information, which is also valid for all other sectors of the economy, a fact that cannot be underestimated by non-profit organizations, namely IPSS, and as such, the accountability practices pursued must be adapted to those entities

[1][2][3].

In fact, IPSS, which are the focus of this study, should verify whether the accountability practice adopted meets the requirements of their stakeholders, as it may affect the effectiveness and fulfilment of their mission

[4]. These authors highlight the primacy given to the economic-financial dimension, to the detriment of other dimensions, which seems contradictory when these organizations have as their main purpose the pursuit of the general interest. The difficulty seems to be, on the one hand, in the lack of an objective definition of quantifiable variables suitable for assessing the impact of the activities developed by the social economy entities, and on the other hand, in the pressure brought to bear by funders and regulatory and supervisory bodies, namely the state.

We cannot fail to highlight the demands placed on IPSS, especially with the entry into force of the revised IPSS statute

[5]. This statute establishes a new model for the financial supervision of IPSS, based on denser and demanding mandatory rules in order to increase transparency in the management and accountability of these entities

[6].

The concept of accountability, initially linked to accounting, has evolved into a quite different reality. Accountability does not refer only to accounting information, but to the actor’s responsibility for all decisions important/relevant to stakeholders, who may demand explanations and justifications

[7]. Additionally, according to this author, the term accountability is increasingly used because it conveys an image of transparency and trust, applicable to any sector, be it the public, private or social economy sector.

According to Bovens

[7], accountability is used as a way of positively qualifying a state of affairs or the performance of an actor. It reflects responsiveness and sense of responsibility, and the will to act in a transparent, fair, and equitable way, but it also refers to concrete accountability practices.

In the case of IPSS, Connolly, and Kelly

[8] emphasized the importance that the reporting of these organizations becomes more reliable and transparent so that with this accounting information of higher quality, one can give visibility to the resources mostly granted by the state, as well as the activities and objectives of the institutions, increasing their notoriety and legitimacy, generating greater confidence among stakeholders. However, the accountability of these institutions goes beyond accounting information, since the decision-making process includes aspects that go beyond this information, simultaneously making the disclosure process more complex, with factors that are more difficult to quantify, such as the social impacts of their activities

[8]. The measurement of this kind of impact generated by an IPSS in the community, normally based on non-accounting information, requires the transformation of qualitative information into useful indicators for all stakeholders (Aimers and Walker, 2008a). For Choudhoury and Ahmed

[9], accountability was focused, until a few decades ago, on internal controls and auditing, monitoring, evaluation, and compliance with rules and regulations. We are now witnessing a paradigm shift: from simple financial accounting to performance auditing and public accountability, i.e., towards all stakeholders.

Becker

[10] pointed out the trend of non-profit organizations to adopt new modalities of accountability, which go beyond the minimum legally imposed requirements. In this way, they will have managed to increase their transparency and implement good governance, simultaneously resulting in increased credibility, reputation, and capacity to attract funders.

From a conceptual point of view, accountability is often used as a synonym for evaluation, and confused with concepts such as responsiveness, responsibility, and effectiveness. In an attempt to analyze a restricted definition of accountability, Bovens

[7] emphasizes the existence of a series of dimensions that are associated with it, both from the relational point of view and in terms of the objectives underlying the various areas of governance. Furthermore, accountability is very often associated with good governance or socially responsible behavior, a very relevant factor as far as the IPSS are concerned.

Tomé, Bandeira, Azevedo and Costa

[11] drew particular attention to the case of IPSS, to whom more and greater challenges are posed by their stakeholders in general, namely: (i) by the state, given the preferential partnership it maintains with these institutions, in addition to its role as regulator; (ii) by private for-profit companies, whose corporate social responsibility programs bring them into regular contact with these organizations; and (iii) by the need for these non-profit entities to become more efficient and effective, open to internal and external reality, facilitating access and perception of their socially responsible behavior, credibility and transparency at all levels, (economic, social and environmental). Fulfilment of all these requirements implies the effective planning and development of activities, the promotion of the evaluation of results and their disclosure, in compliance with legal obligations or other parameters voluntarily expressed but that may help increase their accountability.

All these interpretations suggest the diversity of dimensions in which accountability is established and which characterize institutions and the way in which they interact with their internal and external environments. According to Bergsteiner and Avery

[12], the Integrative Responsibility and Accountability Model considers that two domains exist, the external (accountor) and internal (accountee), which are interconnected—that is, the decisions and perceptions of each influence the other, resulting in responsibilities.

Internally and from their genesis, IPSS should pay special attention to their organizational structure, incorporating new accountability practice mechanisms as a means of increasing knowledge and appropriate forms of governance, promoting their sustainable development

[13]. Other studies analyzed the impact of organizational characteristics on the accountability practices of non-profit organizations, establishing relationships between the organizational profile and the level of accountability

[14][15][16].

Additionally, according to Arshad, Bakar, Thani, and Omar

[17], the composition of management bodies influences accountability practices, whose instruments and associated activities may become, in turn, a useful contribution to the current governance systems, but with effects not yet fully known

[10]. Additionally, of particular interest is a study led by Atan, Alam, and Said

[18], in which the authors assessed the organizational integrity of non-profit organizations and concluded that this contributes significantly to the accountability practices adopted by them.

Equally important is the adequacy of the products and services provided to the community. IPSS cover a broad range of services, particularly in the area of social services, not neglecting education, health, sports, and culture, among others, meeting the specific needs of their community, a fact that also increases the imperativeness of accountability

[19].

With regard to the external environment, of particular importance is the fact that the sustainable development of IPSS is directly linked to the importance of including stakeholders at all levels of decision-making, improving the practice of accountability, from the rendering of accounts to its justification and influence on the level of positive perception

[13]. In the opinion of Aimers and Walker

[20], the partnerships between social economy organizations and the state could lead to difficulties in their relationships with the community, and as a result, they proposed several models for strengthening the integration of these institutions in their communities, through accountability mechanisms, leading to an increase in their accountability.

Awio, Northcott, and Lawrence

[21] added that networks and cooperative actions within groups contribute to improving accountability, in the same way, that voluntarism and reciprocity work to enhance efficiency and accountability, through donations of time, money and material contributions from the community. Participatory monitoring and evaluation by society was the subject of the study by Sangole, Kaaria, Njuki, Lewa, and Mapila

[22], who concluded that these actions strengthen social capital while affecting the community’s perception of the organization’s performance, impacting its accountability.

As mentioned by Ebrhaim

[23], accountability is a complex and dynamic concept that encompasses different types of responsibilities, namely for their actions, for shaping their organizational mission and values, for opening themselves to public or external scrutiny, and for assessing performance in relation to goals. In order to fulfil these different responsibilities, accountability is necessarily associated with several sustainability dimensions (financial, social, environmental, technological, and strategic).

In order to improve the sustainable development of social economy organizations on the one hand, and to increase stakeholder confidence on the other, the need to combine modernization and accountability was documented by Santos, Ferreira, Marques, Azevedo, and Inácio

[24]. They also highlighted the importance of designing quality internal control mechanisms, as a guarantee of good accountability practices, alignment, and integration of all stakeholders, raising performance and trust levels, thus resulting not only in individual growth but also in community development. The impact in terms of contribution to the pursuit of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) should also be highlighted, with a visible result in community terms, but this is often difficult to measure and adequately perceive.

As noted by Ebrahim

[23], still missing with regard to accountability is an integrated look at how organizations deal with multiple and sometimes competing accountability demands, while there continues to be a strong difficulty to include dimensions whose calculations are difficult to determine because they include mostly qualitative data. In Portugal, for example, according to INE

[25], around 46% of the SE entities did not use indicators for monitoring/assessing the performance of their activity and 93% did not use methods for measuring social impact.

2. Accountability Frameworks for Social Economy

Given that many social economy organizations are evaluated by civil society, by the state, or by their patrons and donors, there is a need for the institution to communicate its social effectiveness, herein understood as the ability to attain goals and implement strategies utilizing resources in a socially responsible way

[26]. Thus, according to the triple bottom line (TBL) concept

[27][28], some authors developed frameworks with views to providing a tool to evaluate the accountability of non-profit organizations, observing not only the economic outcome of their activities but also their social and environmental results. However, studies conducted in the social economy field add other concerns beyond the three pillars proposed by the TBL, such as institutional legitimacy

[26], community, and governance

[29]. We are thus led to argue that the TBL is insufficient to communicate, enable understanding and raise awareness among the different stakeholders of social economy entities.

Bagnoli and Megali

[26], based on the production process, proposed a framework based on three dimensions. The first dimension is economic and financial performance, which aims, through the annual accounts, to assess economic efficiency and financial balance. The second is social effectiveness, which aims to assess the capacity to achieve goals and implement strategies using resources in a socially responsible way. This dimension should include indicators related to inputs (resources that contribute to the activities developed), outputs (activities carried out to achieve the mission and direct and accountable goods/services obtained through the activities carried out), results (benefits or impact for the intended beneficiaries), and impact (consequences of the activity for the community at large). The third dimension is that of institutional legitimacy, which involves verifying that the organization has respected its “rules” (statute, mission, action program) and the legal norms applicable to its legal form.

The idea that at the basis of social entrepreneurship lies the concept of social benefit was defended by Arena, Azzone, and Bengo

[30], for whom the ultimate goal for non-profit organizations is the actual “business idea” that needs to be explored, managed and realized. In this sense, and based on an extensive literature review, the authors proposed a framework, called the Performance Model System (PMS), which is structured into four dimensions: (1) financial sustainability (fundamental to ensure service delivery); (2) efficiency (associated with the relationship between material and human resources used and services provided); (3) effectiveness (associated with the characteristics of the output) and the (4) impact (associated with the outcome—a result measure related to the effects of “production” in the long term).

The effectiveness dimension, closely following Bagnoli and Megali

[26], was divided into management effectiveness, related to management strategy and the achievement of objectives, and social effectiveness which concerns the relationship between the non-profit organization and its stakeholders, and which measures the organization’s capacity to meet the needs of its target community by means of the production of goods and services. Due to the importance of this dimension in the social economy sector, the authors divided the social effectiveness dimension into four sub-dimensions: equity (the ability to ensure access to products and services for vulnerable people); involvement (the ability to ensure the participation of relevant stakeholders in the decision-making process) and communication and transparency (the ability to inform stakeholders about the organization’s activities).

In the impact dimension, considering the particularities of non-profit organizations, the authors advocated that one must measure the coherence between the social mission and results. In this sense, the coherence should be evaluated via the connection between the resources employed/used/consumed (inputs), the products/services produced (outputs) and the results achieved (outcomes) that must be consistent with the organization’s mission. In this way, they considered three further sub-dimensions: resource value (the resources used to produce goods or services must be consistent with the organization’s mission); product/service value (the product/service must be consistent with the expected social value of the organization); and outcome value (the final impact of the product or service produced must meet the needs for which the organization works).

Based on the framework presented by Sanford

[31], Gibbons and Jacob

[32] proposed an adaptation that is structured into five dimensions: (1) beneficiaries; (2) cocreators; (3) land/humanity; (4) community and (5) investors/financiers. The beneficiaries are those for whom programs and services are provided (delivered), i.e., stakeholders; the cocreators are those with whom nonprofit organizations have partnerships and may include volunteers, staff, partner organizations, and other stakeholders; land/humanity is the crucial point of the framework, as the relationship with the Earth is applicable to sustainability in any organization, including nonprofit organizations; community refers to how an organization’s actions affect the community, the local perspective and the social context in which they operate; the investors/financiers are funders, contributors, donors, foundations and board members, without whom non-profit organizations could not achieve their mission.

Taking into consideration the particularities of non-profit organizations, Crucke and Decramer

[29] proposed a performance measurement instrument sustained in the reliable, valid, and standardized assessment of organizational performance, building a framework based on five dimensions: (1) economic—related to the economic conditions that underpin a strong financial position, which is important for the viability of the organizations. As such, the focus is not on the financial indicators reported in the annual financial reporting, but on the economic indicators that influence these financial indicators; (2) environmental—focused on the efforts that organizations make to protect nature; (3) human—refers to the relationship the organization has with its workforce; (4) community—refers to the manner in which organizations handle their responsibilities in society, including relationships with dominant stakeholders: beneficiaries of the social mission and customers, paying for the products and services delivered; and (5) governance—refers to “systems and processes concerned with ensuring the overall direction, control, and accountability of an organization”. The governance performance is a specific performance domain, as good governance practices are expected to have a positive impact on organizational decision making, positively influencing the other performance domains of the organization. When developing this tool, the authors considered that performance is multidimensional and that when assessing performance, the inputs, activities, and outputs should be considered, but not their impact (outcomes). In this decision, they took into consideration Ebrahim and Rangan’s

[33] arguments that the conviction to consider outcomes and impacts would be an impediment to developing an adequate tool for social enterprises with diverse activities. For the Portuguese case, considering that social economy entities must behave in a socially responsible manner, Tomé, Meira, and Bandeira

[6] proposed a framework organized into the following five categories: (1) human resources; (2) products and services; (3) sustainability; (4) relationship with the community and (5) environmental.

Table 1 presents the summary of accountability frameworks developed specifically for the social economy sector.

Table 1. Summary of accountability frameworks for social economy.

| Author |

Framework Dimensions |

Based on |

| Bagnoli and Megali [26] |

Economic and financial performance; social effectiveness; institutional legitimacy |

Production process |

| Arena, Azzone and Bengo [30] |

Financial sustainability, efficiency; effectiveness; impact |

Social benefit |

| Gibbons and Jacob [32] |

Beneficiaries; cocreators; land/humanity; community; investors/financiers |

Responsible and sustainable behavior |

| Crucker and Decramer [29] |

Economic; environmental; human; community; governance |

Internal and external assessment of non-financial performance |

| Tomé, Meira and Bandeira [6] |

Human resources; products and services; sustainability; relationship with community; environment |

Responsible social behavior |

According to Marques, Santos, and Duarte

[34], the assessment of accountability is still limited due to the absence of a framework that adequately implements accountability practices in all its dimensions. These authors advocated that the use of new information and communication technologies (ICTs) can contribute to the modernization of the sector, through the creation of institutional websites, where institutions can disclose financial and non-financial information, allowing their stakeholders to assess their mode of operation and performance. The motivation of stakeholders may be improved as the websites become better and more proactive, and both circumstances will contribute to increasing the legitimacy and notoriety of these institutions, with consequent advantages at all levels.

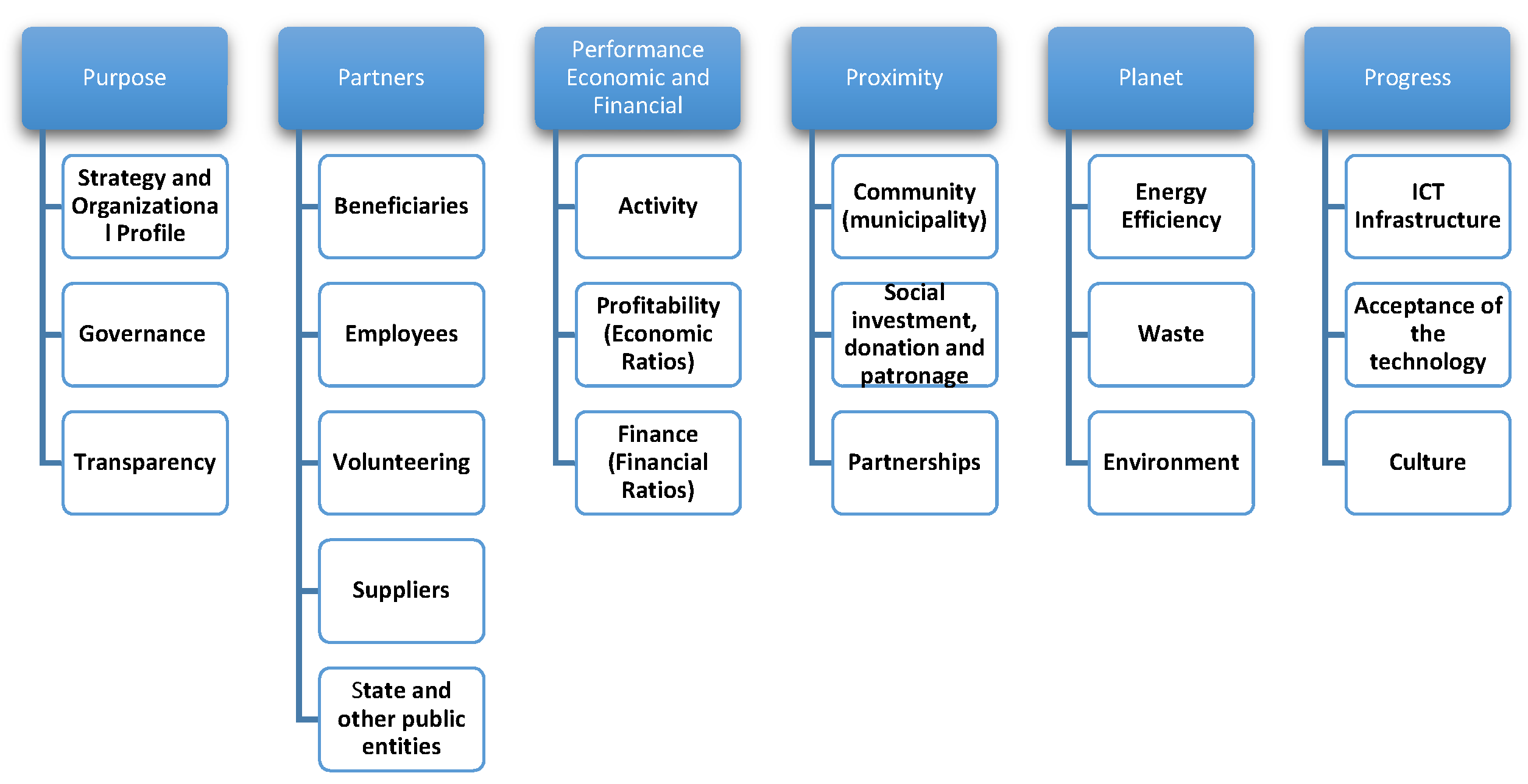

Based on the literature review, we propose a framework organized according to the sextuplet bottom line (SBL) concept with the following dimensions: purpose; partners (extended people concept); profit; proximity; planet; and progress. Each dimension has sub-dimensions as in the figure below.

For each dimension/sub-dimension, the indicators considered capable of expressing the relevant information were defined, improving the accountability of the IPSS.