| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | David Waisman | + 2487 word(s) | 2487 | 2021-11-29 09:14:51 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | -3 word(s) | 2484 | 2022-01-20 02:47:42 | | |

Video Upload Options

The plasminogen activator/plasmin system is an enzymatic cascade involved in the control of multiple physiological processes, including fibrin degradation, matrix turnover, phagocytosis, inflammation, and wound healing. Plasmin also plays a critical role during the multiple steps of cancer invasion and metastasis by participating in the degradation of several extracellular matrix proteins and activating certain growth factors, resulting in aggressive cancers. Many tumors show robust fibrinolytic activity due to the enhanced release of plasminogen activators and the stimulated expression of plasminogen receptors such as the annexin A2/S100A10 hetotetramer (AIIt). It is now apparent that within the heterotetramer, annexin A2 functions as a tethering protein while S100A10 binds and activates plasminogen. The key event in the activation of plasminogen by plasminogen receptors involves the interaction of internal lysine and/or carboxyl-terminal lysine residues with the lysine binding domains (kringles) of plasminogen.

1. Introduction

Peyton Rous initially demonstrated that a cell-free agent isolated from chicken sarcoma was capable of infecting healthy tissues and forming sarcomas with “extreme malignancy and a tendency to wide-spread metastasis” [1]. The virus responsible for the formation of these sarcomas was later named Rous Sarcoma Virus (RSV), and the transforming ability of RSV was demonstrated to be entirely due to a single gene product of the virus, namely the viral src oncogene (vSrc). The antisera from rabbits bearing tumors induced by RSV was utilized to immunoprecipitate the 60 kDa src gene product from RSV-transformed cells [2]. Subsequently, in vitro translation reactions programmed with Src virion RNA successfully generated the 60 kDa gene product [3]. The immunoprecipitates of pp60v-src obtained with the antisera were subsequently shown to possess a protein kinase activity that, in the presence of ATP and Mg2+, phosphorylated the immunoglobulin heavy chain [4][5]. Analysis of the phosphorylation sites demonstrated that the v-Src gene product was a protein-tyrosine kinase, which was subsequently named pp60src [6][7]. The pp60src was shown to be responsible for several molecular events and phenotypic changes observed in transformed host cells [8]. Phosphorylation of cellular substrates on tyrosine residues by pp60vsrc kinase was suggested to be the event responsible for transforming RSV-infected cells into cancer cells [6].

Fisher [9] first observed that avian tissue explants transformed to malignancy by viruses, such as RSV, generate high levels of fibrinolytic activity under conditions in which cultures of normal tissues do not. Fisher demonstrated that when chicken sarcomas were placed on fibrin gels, robust digestion of the gel occurred. He called the enzyme responsible for the fibrin digestion fibrinolysin, which would later be renamed plasmin. Later, Reich reported that chick embryo fibroblast cultures transformed with RSV exhibited robust fibrinolytic activity. This fibrinolytic activity was not present in traditional cultures and did not appear after infection with either non-transforming strains of avian leukosis viruses or cytocidal RNA and DNA viruses [10]. Reich then demonstrated that fibrinolysin was produced by the interaction of two protein factors, one of which was a factor released by transformed cells and a second factor was a serum protein [11][12]. The serum factor was purified and identified as the zymogen plasminogen [10][11], and the cell factor was shown to be a specific serine protease that functioned as a plasminogen activator [12]. Other laboratories have confirmed that the robustly induced enzymatic activity in RSV-transformed chicken cells was the plasminogen activator, now called the urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA). The uPA is encoded by the uPA gene (PLAU). The transcriptional induction of the PLAU gene was shown to be the most highly upregulated transcript in RSV transformed fibroblasts [13]. Subsequently, Loskutoff demonstrated that cultures of normal endothelial cells released plasminogen activators, and therefore, endothelial cells activated fibrinolysis by the release of these plasminogen activators [14].

The discovery that the SRC gene product coded for a protein-tyrosine kinase was an exciting event because it suggested that the activity of a single enzyme and the phosphorylation of several key proteins on tyrosine residues could initiate and potentiate cancer (in chickens). Hunter and Sefton reported that chicken fibroblasts transformed by RSV contained as much as 8-fold more phosphotyrosine than uninfected cells [6]. Consequently, a search was initiated to identify the vital cellular proteins that were phosphorylated on their tyrosine residues by pp60src and, by inference, would be responsible for converting normal cells to cancer cells. Subsequently, a 36-kDa protein (annexin A2, ANXA2) that underwent phosphorylation on tyrosine residues after transformation by RSV was identified as one of the most prominent phosphoproteins [15][16][17]. Furthermore, this protein was shown to exist in a complex with an 8-10K binding partner [18][19][20] in a heterotetramer form. This heterotetrameric complex, later known as the ANXA2/S100A10 complex (AIIt), would subsequently be shown to be an important plasminogen binding protein that greatly stimulated the conversion of plasminogen to plasmin by the plasminogen activators uPA and tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) [21][22][23]. Therefore, AIIt provided a conceptual bridge between malignant cancer cells and fibrinolysis.

2. Plasminogen Activation

The circulating form of plasminogen, amino-terminal glutamic acid [Glu]-plasminogen, is a single-chain multidomain glycoprotein of 90 kDa composed of 791 amino acids, divided into 7 different structural domains. These domains consist of an N-terminus peptide domain, five tandem protein-protein interaction domains called kringles (K1–K5), and a C-terminus catalytic domain [24][25][26]. The kringle domains bind to target proteins such as fibrin and plasminogen receptors. Four out of these five domains (K1, K2, K4, and K5) contain lysine-binding sites that interact with the lysine residues of plasminogen receptors. The kringles of plasminogen that possess lysine-binding sites consist of three distinct binding regions, the anionic center, the hydrophobic groove, and the cationic center. The anionic center is composed of two acidic residues which interact with the amino group side-chain of lysine. The hydrophobic groove typically consists of several residues, typically tryptophan or tyrosine, which interact with the side-chain methylene backbone of lysine. Finally, the cationic center comprises one or two basic residues, namely a lysine or arginine, and this region interacts with the free carboxylate group of lysine. Significantly, only plasminogen receptor proteins with carboxyl-terminal lysines possess a free carboxylate group that can interact with all three binding regions of the kringle domain of plasminogen.

Plasminogen can adopt two distinct conformations, referred to as closed and open conformations [27][28][29][30][31]. Glu-plasminogen circulates in the blood in the closed conformation, which cannot be readily activated by tPA or uPA. The binding of Glu-plasminogen to fibrin or plasminogen receptors results in a conformational change in Glu-plasminogen to the open conformation. In the open conformation, the activation loop is exposed and readily cleaved by tPA or uPA. Removal of the N-terminal peptide region of Glu-plasminogen by plasmin produces an alternative zymogen form of plasminogen called Lys-plasminogen, which also adopts an open conformation. The open forms of plasminogen are converted to the active serine protease, plasmin, through cleavage in its activation loop domain, between Arg 561 and Val 562, by tPA or uPA.

The plasminogen activator/plasmin system is an enzymatic cascade involved in the control of multiple physiological processes, including fibrin degradation [32][33][34], matrix turnover [35], phagocytosis [36][37], inflammation [38], and wound healing [39]. Plasmin also plays a critical role during the multiple steps of cancer invasion and metastasis by participating in the degradation of several extracellular matrix proteins and activating certain growth factors, resulting in aggressive cancers [40][41][42].

3. Plasminogen Receptors

The rate of plasminogen activation by the plasminogen activators is very slow. The plasminogen receptors function to stimulate tPA- and uPA-dependent plasminogen activation. In addition, they localize plasmin proteolytic activity to the cell surface and also protect both the plasminogen activators and plasmin from rapid inactivation by the abundant inhibitors that surround cells (reviewed in [43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50]). Plasminogen receptors are broadly distributed on both eukaryotic and prokaryotic cell types, and the majority of cells have a high capacity for binding plasminogen. Typically, the affinity for plasminogen-binding by cells ranges between 0.5–2 μM, and purified plasminogen receptors typically bind plasminogen with micromolar affinity in cellulo and with variable numbers of binding sites varying from 10 7 to 10 5 sites/cell [50][51]. It was originally demonstrated that cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells bound plasminogen with a Kd = 2 μM and 1.8 × 107 binding sites/cell [52] and platelets with a Kd = 2 μM and 0.037 × 106 sites [53]. Most recently, Ranson showed that viable MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells bind plasminogen with moderate affinity and high capacity (Kd of 1.8 μM, and 5.0 × 107 receptor sites per cell) [54].

The mechanism of interaction of plasminogen with plasminogen receptors has been evaluated in detail by Law [24]. They reported the crystal structure of plasminogen and suggested that K1 mediates the initial docking of plasminogen with fibrin or the cell surface. Law also reported that K5 is transiently exposed in plasminogen, such that it could interact with lysine residues of the plasminogen receptor, resulting in a conformational change. However, K5 preferentially binds internal lysine residues since it does not possess the cationic center essential for binding to the carboxyl moiety of a carboxyl-terminal lysine. Law suggested that two lysine residues are required to bind cooperatively to K5 and then K4 to trigger a conformational change in plasminogen. The involvement of more than one lysine of the plasminogen receptor in plasminogen binding suggests at the very least that a carboxyl-terminal lysine and two internal lysines may participate in plasminogen activation.

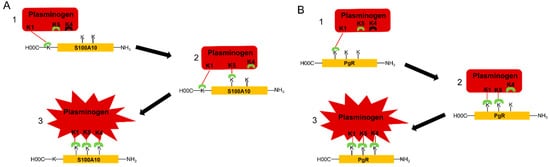

Two models for the binding of plasminogen to plasminogen receptors were mentioned in figure 1. The interaction of K1 of plasminogen with the carboxyl-terminal lysine of carboxyl-terminal lysine-type plasminogen receptors triggers a conformational change in plasminogen resulting in the surface exposure of K5, which binds to an internal lysine of the plasminogen receptor. This results in another conformational change in which K4 is surface exposed, allowing it to bind to a second internal lysine residue on the plasminogen receptor resulting in an additional conformational change in plasminogen to the activatable conformation. Therefore, we predict that the interaction of plasminogen with carboxyl-terminal lysine-type plasminogen receptors requires the participation of one carboxyl-terminal lysine and two internal lysines. We also predict that the interaction of plasminogen with plasminogen receptors that do not possess carboxyl-terminal lysines involves the interaction of K1 of plasminogen with an internal lysine, referred to as the initiating lysine, which then results in the exposure of K5 and then K4 and a conformational change to the activatable conformation. Accordingly, we expect that each of these kringle domains interacts with a distinct internal lysine residue. It is unclear if the initiating lysine is unique in terms of reactivity with K1 or if the three internal lysines have a unique spatial orientation that favors the three-point binding of plasminogen.

Several plasminogen receptors participate in the movement of macrophages to the tumor site. As extensively discussed by Plow [50], analysis of the relative contribution of the well-documented plasminogen receptors to macrophage recruitment was calculated to be: histone H2B (45%), S100A10 (53%), and Plg-RKT (58%). Thus the contribution of these receptors exceeds 100% and therefore suggests redundancy in the role of plasminogen receptors in physiological processes. Accordingly, Plow suggested that a threshold of bound plasminogen must be attained for plasminogen to facilitate cell migration and that no single plasminogen receptor might harness sufficient plasmin generation to reach this threshold, and, therefore, cooperation among several plasminogen receptors may be required to complete the physiological response.

4. Is ANXA2 a Plasminogen Receptor?

Extensive studies from our laboratory and others have shown that AIIt and specifically the S100A10 subunit is a plasminogen receptor. Previous reports have claimed that ANXA2 can bind both tPA and plasminogen [55] (reviewed in [56]). These studies were based on an analysis of ANXA2 purified from the placenta by calcium precipitation followed by isolation from polyacrylamide gels. Since carboxypeptidase B, a protease that removes the carboxyl-terminal lysines from proteins, blocked the ability of the polyacrylamide gel-purified ANXA2 to activate plasminogen, the authors concluded that the form of ANXA2 that bound plasminogen required post-translational processing at Lys-307. The authors also reported that the intact ANXA2 1–338 did not bind or activate plasminogen. In the almost 40 years that followed, the ANXA2 1–307 form has not been identified by laboratories that have purified ANXA2 or AIIt from tissues or have analyzed ANXA2 on the cell surface [57][58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66]. For example, the molecular weight of purified bovine lung ANXA2, determined by ESI-MS, is 38,519.82 ± 3.29 [67].

Recently, Hajjar revisited the issue of the existence of the ANXA2 1–307 form. They analyzed patient samples and concluded that post-translationally processed or proteolyzed forms of ANXA2 were not present [68]. Therefore, in the absence of any evidence to the contrary, we must conclude that ANXA2 is not a plasminogen receptor.

Multiple reports have demonstrated that depletion of ANXA2 in cultured cells resulted in the loss of plasmin generation and reduction in plasmin generation, tumor burden, invasiveness, and metastasis (reviewed in [69]). Typically these reports fail to discuss the fact that S100A10 is protected from rapid degradation by ANXA2, and therefore, the loss of ANXA2 from cells results in the loss of S100A10 [70][71][72][73][74]. The loss of S100A10 does not affect the ANXA2 levels [75][76]. The experimental approach involving depletion of ANXA2 is not adequate or sufficient to establish a role of ANXA2 in any physiological process since these studies disregarded the individual contribution of ANXA2 and S100A10 to plasmin regulation. For example, S100A10 regulates 50–90% of the plasmin generation of most cells [69], and it is therefore expected that any ANXA2-mediated changes in S100A10 levels will have profound effects on plasmin generation and any other S100A10-related functions. Furthermore, we have shown that depletion of ANXA2 in telomerase immortalized microvascular endothelial cells leads to the loss of plasminogen binding and plasmin generation, similar to when S100A10 is depleted [76]. Therefore, we conclude that depletion of ANXA2 is not adequate or sufficient to establish the role of ANXA2 in any physiological process unless the role of S100A10 in that process is determined. If the depletion of S100A10 fails to inhibit a process that is inhibited by depletion of ANXA2, then it is reasonable to suspect the role of ANXA2 and not S100A10 in that process.

References

- Rous, P. A sarcoma of the fowl transmissible by an agent separable from the tumor cells. J. Exp. Med. 1911, 13, 397–411.

- Brugge, J.S.; Erikson, R.L. Identification of a Transformation-Specific Antigen Induced by an Avian Sarcoma Virus. Nature 1977, 269, 346–348.

- Purchio, A.F.; Erikson, E.; Brugge, J.S.; Erikson, R.L. Identification of a Polypeptide Encoded by the Avian Sarcoma Virus Src Gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1978, 75, 1567–1571.

- Collett, M.S.; Erikson, R.L. Protein Kinase Activity Associated with the Avian Sarcoma Virus Src Gene Product. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1978, 75, 2021–2024.

- Levinson, A.D.; Oppermann, H.; Levintow, L.; Varmus, H.E.; Bishop, J.M. Evidence That the Transforming Gene of Avian Sarcoma Virus Encodes a Protein Kinase Associated with a Phosphoprotein. Cell 1978, 15, 561–572.

- Hunter, T.; Sefton, B.M. Transforming Gene Product of Rous Sarcoma Virus Phosphorylates Tyrosine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1980, 77, 1311–1315.

- Collett, M.S.; Purchio, A.F.; Erikson, R.L. Avian Sarcoma Virus-Transforming Protein, pp60 src Shows Protein Kinase Activity Specific for Tyrosine. Nature 1980, 285, 167–169.

- Jove, R.; Hanafusa, H. Cell Transformation by the Viral Src Oncogene. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 1987, 3, 31–56.

- Fischer, A. Beitrag Zur Biologie Der Gewebezellen. Eine Vergleichendbiologische Studie Der Normalen Und Malignen Gewebezellen In Vitro. Arch. Entwickl. Org. Wilhelm Roux 1925, 104, 210–261.

- Unkeless, J.C.; Tobia, A.; Ossowski, L.; Quigley, J.P.; Rifkin, D.B.; Reich, E. An Enzymatic Function Associated with Transformation of Fibroblasts by Oncogenic Viruses. I. Chick Embryo Fibroblast Cultures Transformed by Avian RNA Tumor Viruses. J. Exp. Med. 1973, 137, 85–111.

- Ossowski, L.; Quigley, J.P.; Kellerman, G.M.; Reich, E. Fibrinolysis Associated with Oncogenic Transformation. Requirement of Plasminogen for Correlated Changes in Cellular Morphology, Colony Formation in Agar, and Cell Migration. J. Exp. Med. 1973, 138, 1056–1064.

- Ossowski, L.; Unkeless, J.C.; Tobia, A.; Quigley, J.P.; Rifkin, D.B.; Reich, E. An Enzymatic Function Associated with Transformation of Fibroblasts by Oncogenic Viruses. II. Mammalian Fibroblast Cultures Transformed by DNA and RNA Tumor Viruses. J. Exp. Med. 1973, 137, 112–126.

- Maślikowski, B.M.; Néel, B.D.; Wu, Y.; Wang, L.; Rodrigues, N.A.; Gillet, G.; Bédard, P.-A. Cellular Processes of V-Src Transformation Revealed by Gene Profiling of Primary Cells-Implications for Human Cancer. BMC Cancer 2010, 10, 41.

- Levin, E.G.; Loskutoff, D.J. Cultured Bovine Endothelial Cells Produce Both Urokinase and Tissue-Type Plasminogen Activators. J. Cell Biol. 1982, 94, 631–636.

- Erikson, E.; Erikson, R.L. Identification of a Cellular Protein Substrate Phosphorylated by the Avian Sarcoma Virus-Transforming Gene Product. Cell 1980, 21, 829–836.

- Radke, K.; Martin, G.S. Transformation by Rous Sarcoma Virus: Effects of Src Gene Expression on the Synthesis and Phosphorylation of Cellular Polypeptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1979, 76, 5212–5216.

- Gould, K.L.; Cooper, J.A.; Hunter, T. The 46,000-Dalton Tyrosine Protein Kinase Substrate Is Widespread, Whereas the 36,000-Dalton Substrate Is Only Expressed at High Levels in Certain Rodent Tissues. J. Cell Biol. 1984, 98, 487–497.

- Erikson, E.; Tomasiewicz, H.G.; Erikson, R.L. Biochemical Characterization of a 34-Kilodalton Normal Cellular Substrate of Pp60v-Src and an Associated 6-Kilodalton Protein. Mol. Cell Biol. 1984, 4, 77–85.

- Glenney, J.R.; Tack, B.F. Amino-Terminal Sequence of P36 and Associated P10: Identification of the Site of Tyrosine Phosphorylation and Homology with S-100. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1985, 82, 7884–7888.

- Gerke, V.; Weber, K. Identity of P36K Phosphorylated upon Rous Sarcoma Virus Transformation with a Protein Purified from Brush Borders; Calcium-Dependent Binding to Non-Erythroid Spectrin and F-Actin. EMBO J. 1984, 3, 227–233.

- Kassam, G.; Le, B.H.; Choi, K.S.; Kang, H.M.; Fitzpatrick, S.L.; Louie, P.; Waisman, D.M. The P11 Subunit of the Annexin II Tetramer Plays a Key Role in the Stimulation of T-PA-Dependent Plasminogen Activation. Biochemistry 1998, 37, 16958–16966.

- Kassam, G.; Choi, K.S.; Ghuman, J.; Kang, H.M.; Fitzpatrick, S.L.; Zackson, T.; Zackson, S.; Toba, M.; Shinomiya, A.; Waisman, D.M. The Role of Annexin II Tetramer in the Activation of Plasminogen. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 4790–4799.

- Choi, K.S.; Ghuman, J.; Kassam, G.; Kang, H.M.; Fitzpatrick, S.L.; Waisman, D.M. Annexin II Tetramer Inhibits Plasmin-Dependent Fibrinolysis. Biochemistry 1998, 37, 648–655.

- Law, R.H.P.; Abu-Ssaydeh, D.; Whisstock, J.C. New Insights into the Structure and Function of the Plasminogen/Plasmin System. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2013, 23, 836–841.

- Claeys, H.; Sottrup-Jensen, L.; Zajdel, M.; Petersen, T.E.; Magnusson, S. Multiple Gene Duplication in the Evolution of Plasminogen. Five Regions of Sequence Homology with the Two Internally Homologous Structures in Prothrombin. FEBS Lett. 1976, 61, 20–24.

- Sottrup-Jensen, L.; Claeys, H.; Zajdel, M.; Petersen, T.E.; Magnusson, S. The Primary Structure of Human Plasminogen; Isolation of Two Lysine-Binding Fragments and One Mini-Plasminogen by Elastase-Catalysed-Specific Limited Proteolysis. In Progress in Chemical Fibrinolysis and Thrombosis; Raven Press: New York, NY, USA, 1978; pp. 191–209.

- Mangel, W.F.; Lin, B.H.; Ramakrishnan, V. Characterization of an Extremely Large, Ligand-Induced Conformational Change in Plasminogen. Science 1990, 248, 69–73.

- Kornblatt, J.A.; Rajotte, I.; Heitz, F. Reaction of Canine Plasminogen with 6-Aminohexanoate: A Thermodynamic Study Combining Fluorescence, Circular Dichroism, and Isothermal Titration Calorimetry. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 3639–3647.

- Han, J.; Baik, N.; Kim, K.-H.; Yang, J.-M.; Han, G.W.; Gong, Y.; Jardí, M.; Castellino, F.J.; Felez, J.; Parmer, R.J.; et al. Monoclonal Antibodies Detect Receptor-Induced Binding Sites in Glu-Plasminogen. Blood 2011, 118, 1653–1662.

- Xue, Y.; Bodin, C.; Olsson, K. Crystal Structure of the Native Plasminogen Reveals an Activation-Resistant Compact Conformation. J. Thromb. Haemost. JTH 2012, 10, 1385–1396.

- Horrevoets, A.J.; Smilde, A.E.; Fredenburgh, J.C.; Pannekoek, H.; Nesheim, M.E. The Activation-Resistant Conformation of Recombinant Human Plasminogen Is Stabilized by Basic Residues in the Amino-Terminal Hinge Region. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 15770–15776.

- Medcalf, R.L. Fibrinolysis: From Blood to the Brain. J. Thromb. Haemost. JTH 2017, 15, 2089–2098.

- Medcalf, R.L.; Keragala, C.B. The Fibrinolytic System: Mysteries and Opportunities. HemaSphere 2021, 5, e570.

- Longstaff, C.; Kolev, K. Basic Mechanisms and Regulation of Fibrinolysis. J. Thromb. Haemost. JTH 2015, 13 (Suppl. S1), S98–S105.

- Stoppelli, M.P. The Plasminogen Activation System in Cell Invasion; Landes Bioscience: Austin, TX, USA, 2013.

- Das, R.; Ganapathy, S.; Settle, M.; Plow, E.F. Plasminogen Promotes Macrophage Phagocytosis in Mice. Blood 2014, 124, 679–688.

- Rosenwald, M.; Koppe, U.; Keppeler, H.; Sauer, G.; Hennel, R.; Ernst, A.; Blume, K.E.; Peter, C.; Herrmann, M.; Belka, C.; et al. Serum-Derived Plasminogen Is Activated by Apoptotic Cells and Promotes Their Phagocytic Clearance. J. Immunol. Baltim. J. Immunol. 2012, 189, 5722–5728.

- Baker, S.K.; Strickland, S. A Critical Role for Plasminogen in Inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217.

- Lijnen, H.R.; Van Hoef, B.; Lupu, F.; Moons, L.; Carmeliet, P.; Collen, D. Function of the Plasminogen/Plasmin and Matrix Metalloproteinase Systems After Vascular Injury in Mice With Targeted Inactivation of Fibrinolytic System Genes. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1998, 18, 1035–1045.

- Wyganowska-Świątkowska, M.; Tarnowski, M.; Murtagh, D.; Skrzypczak-Jankun, E.; Jankun, J. Proteolysis Is the Most Fundamental Property of Malignancy and Its Inhibition May Be Used Therapeutically (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019, 43, 15–25.

- McMahon, B.J.; Kwaan, H.C. Components of the Plasminogen-Plasmin System as Biologic Markers for Cancer. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2015, 867, 145–156.

- Didiasova, M.; Wujak, L.; Wygrecka, M.; Zakrzewicz, D. From Plasminogen to Plasmin: Role of Plasminogen Receptors in Human Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 21229–21252.

- Godier, A.; Hunt, B.J. Plasminogen Receptors and Their Role in the Pathogenesis of Inflammatory, Autoimmune and Malignant Disease. J. Thromb. Haemost. JTH 2013, 11, 26–34.

- Miles, L.A.; Hawley, S.B.; Baik, N.; Andronicos, N.M.; Castellino, F.J.; Parmer, R.J. Plasminogen Receptors: The Sine qua Non of Cell Surface Plasminogen Activation. Front. Biosci. 2005, 10, 1754–1762.

- Miles, L.A.; Parmer, R.J. Plasminogen Receptors: The First Quarter Century. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2013, 39, 329–337.

- Miles, L.A.; Plow, E.F.; Waisman, D.M.; Parmer, R.J. Plasminogen Receptors. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012, 2012, 130735.

- Miles, L.A.; Ny, L.; Wilczynska, M.; Shen, Y.; Ny, T.; Parmer, R.J. Plasminogen Receptors and Fibrinolysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1712.

- Bharadwaj, A.G.; Holloway, R.W.; Miller, V.A.; Waisman, D.M. Plasmin and Plasminogen System in the Tumor Microenvironment: Implications for Cancer Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Therapy. Cancers 2021, 13, 1838.

- Herren, T.; Swaisgood, C.; Plow, E.F. Regulation of Plasminogen Receptors. Front. Biosci. 2003, 8, D1–D8.

- Plow, E.F.; Doeuvre, L.; Das, R. So Many Plasminogen Receptors: Why? J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012, 2012, 141806.

- Felez, J. Plasminogen Binding to Cell Surfaces. Fibrinolysis Proteolysis 1998, 12, 183–189.

- Miles, L.A.; Levin, E.G.; Plescia, J.; Collen, D.; Plow, E.F. Plasminogen Receptors, Urokinase Receptors, and Their Modulation on Human Endothelial Cells. Blood 1988, 72, 628–635.

- Miles, L.A.; Plow, E.F. Binding and Activation of Plasminogen on the Platelet Surface. J. Biol. Chem. 1985, 260, 4303–4311.

- Ranson, M.; Andronicos, N.M.; O’Mullane, M.J.; Baker, M.S. Increased Plasminogen Binding Is Associated with Metastatic Breast Cancer Cells: Differential Expression of Plasminogen Binding Proteins. Br. J. Cancer 1998, 77, 1586–1597.

- Hajjar, K.A.; Jacovina, A.T.; Chacko, J. An Endothelial Cell Receptor for Plasminogen/Tissue Plasminogen Activator. I. Identity with Annexin II. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 21191–21197.

- Bydoun, M.; Waisman, D.M. On the Contribution of S100A10 and Annexin A2 to Plasminogen Activation and Oncogenesis: An Enduring Ambiguity. Future Oncol. Lond. Engl. 2014, 10, 2469–2479.

- Kwon, M.; Yoon, C.S.; Jeong, W.; Rhee, S.G.; Waisman, D.M. Annexin A2-S100A10 Heterotetramer, a Novel Substrate of Thioredoxin. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 23584–23592.

- Chung, C.Y.; Erickson, H.P. Cell Surface Annexin II Is a High Affinity Receptor for the Alternatively Spliced Segment of Tenascin-C. J. Cell Biol. 1994, 126, 539–548.

- Römisch, J.; Heimburger, N. Purification and Characterization of Six Annexins from Human Placenta. Biol. Chem. Hoppe. Seyler 1990, 371, 383–388.

- Khanna, N.C.; Helwig, E.D.; Ikebuchi, N.W.; Fitzpatrick, S.; Bajwa, R.; Waisman, D.M. Purification and Characterization of Annexin Proteins from Bovine Lung. Biochemistry 1990, 29, 4852–4862.

- Regnouf, F.; Rendon, A.; Pradel, L.A. Biochemical Characterization of Annexins I and II Isolated from Pig Nervous Tissue. J. Neurochem. 1991, 56, 1985–1996.

- Buhl, W.J.; García, M.T.; Zipfel, M.; Schiebler, W.; Gehring, U. A Series of Annexins from Human Placenta and Their Characterization by Use of an Endogenous Phospholipase A2. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 1991, 56, 381–390.

- Kaetzel, M.A.; Hazarika, P.; Dedman, J.R. Differential Tissue Expression of Three 35-KDa Annexin Calcium-Dependent Phospholipid-Binding Proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 14463–14470.

- Shadle, P.J.; Gerke, V.; Weber, K. Three Ca2+-Binding Proteins from Porcine Liver and Intestine Differ Immunologically and Physicochemically and Are Distinct in Ca2+ Affinities. J. Biol. Chem. 1985, 260, 16354–16360.

- Martin, F.; Derancourt, J.; Capony, J.P.; Watrin, A.; Cavadore, J.C. A 36 KDa Monomeric Protein and Its Complex with a 10 KDa Protein Both Isolated from Bovine Aorta Are Calpactin-like Proteins That Differ in Their Ca2+-Dependent Calmodulin-Binding and Actin-Severing Properties. Biochem. J. 1988, 251, 777–785.

- Huang, K.-S.; Wallner, B.P.; Mattaliano, R.J.; Tizard, R.; Burne, C.; Frey, A.; Hession, C.; McGray, P.; Sinclair, L.K.; Chow, E.P.; et al. Two Human 35 Kd Inhibitors of Phospholipase A2 Are Related to Substrates of Pp60v-Src and of the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor/Kinase. Cell 1986, 46, 191–199.

- Kang, H.M.; Kassam, G.; Jarvis, S.E.; Fitzpatrick, S.L.; Waisman, D.M. Characterization of Human Recombinant Annexin II Tetramer Purified from Bacteria: Role of N-Terminal Acetylation. Biochemistry 1997, 36, 2041–2050.

- Fassel, H.; Chen, H.; Ruisi, M.; Kumar, N.; DeSancho, M.; Hajjar, K.A. Reduced Expression of Annexin A2 Is Associated with Impaired Cell Surface Fibrinolysis and Venous Thromboembolism. Blood 2021, 137, 2221–2230.

- Bharadwaj, A.; Bydoun, M.; Holloway, R.; Waisman, D. Annexin A2 Heterotetramer: Structure and Function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 6259–6305.

- Puisieux, A.; Ji, J.; Ozturk, M. Annexin II Up-Regulates Cellular Levels of P11 Protein by a Post-Translational Mechanisms. Biochem. J. 1996, 313 Pt 1, 51–55.

- Zhang, J.; Guo, B.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, J.; Chen, T. Silencing of the Annexin II Gene Down-Regulates the Levels of S100A10, c-Myc, and Plasmin and Inhibits Breast Cancer Cell Proliferation and Invasion. Saudi Med. J. 2010, 31, 374–381.

- Hou, Y.; Yang, L.; Mou, M.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, A.; Pan, N.; Qiang, R.; Wei, L.; Zhang, N. Annexin A2 Regulates the Levels of Plasmin, S100A10 and Fascin in L5178Y Cells. Cancer Investig. 2008, 26, 809–815.

- Gladwin, M.T.; Yao, X.L.; Cowan, M.; Huang, X.L.; Schneider, R.; Grant, L.R.; Logun, C.; Shelhamer, J.H. Retinoic Acid Reduces P11 Protein Levels in Bronchial Epithelial Cells by a Posttranslational Mechanism. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2000, 279, L1103-9.

- Yang, X.; Popescu, N.C.; Zimonjic, D.B. DLC1 Interaction with S100A10 Mediates Inhibition of in Vitro Cell Invasion and Tumorigenicity of Lung Cancer Cells through a RhoGAP-Independent Mechanism. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 2916–2925.

- Lu, H.; Xie, Y.; Tran, L.; Lan, J.; Yang, Y.; Murugan, N.L.; Wang, R.; Wang, Y.J.; Semenza, G.L. Chemotherapy-Induced S100A10 Recruits KDM6A to Facilitate OCT4-Mediated Breast Cancer Stemness. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 4607–4623.

- Surette, A.P.; Madureira, P.A.; Phipps, K.D.; Miller, V.A.; Svenningsson, P.; Waisman, D.M. Regulation of Fibrinolysis by S100A10 in Vivo. Blood 2011, 118, 3172–3181.