Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tancredi Pascucci | + 1861 word(s) | 1861 | 2022-01-11 03:58:30 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | -48 word(s) | 1813 | 2022-01-19 02:15:42 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Pascucci, T. Positive Factors for Entrepreneurial Resilience. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18434 (accessed on 12 March 2026).

Pascucci T. Positive Factors for Entrepreneurial Resilience. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18434. Accessed March 12, 2026.

Pascucci, Tancredi. "Positive Factors for Entrepreneurial Resilience" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18434 (accessed March 12, 2026).

Pascucci, T. (2022, January 18). Positive Factors for Entrepreneurial Resilience. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18434

Pascucci, Tancredi. "Positive Factors for Entrepreneurial Resilience." Encyclopedia. Web. 18 January, 2022.

Copy Citation

“Resilience” is a term borrowed from Civil Engineering, which defines a material that has good resistance under pressure, is also used in Individual Psychology to define good adaptation during difficulties and has similarly been adopted in Management Science to define a “resistant” organization that can survive without significant impairment during international crises.

sustainability

resilience

social impact

empowerment

1. Introduction

Crises in the last 20 years and throughout the 20th century have reached international proportions, often based on economic triggers. For example, two world wars occurred as a consequence of political and economic expansion, the Great Depression followed the Wall Street (NY, USA) crash of 1929, the 1973 petroleum crisis, the capitalist re-invention of former Soviet republics following the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Great Recession of 2007–2009 and, more recently, the COVID-19 recession as a consequence of the pre-existing vulnerability of socio-economic systems around the world, which led to the chaotic management of the flow of goods and people around the world [1][2]. These events stressed the need for Entrepreneurship Education (EE) to equip new and existing entrepreneurs with the managerial and entrepreneurial skills to manage similar difficulties and prevent similar crises in the future. A firm’s survival depends on its ability to withstand difficulties, and it can be defined as “resilient” if it can adapt positively without altering its mission. [3][4][5][6]. “Resilience” is a term borrowed from Civil Engineering, which defines a material that has good resistance under pressure, is also used in Individual Psychology to define good adaptation during difficulties and has similarly been adopted in Management Science to define a “resistant” organization that can survive without significant impairment during international crises [7][8][9]. Not every business organization is resilient, and those that are are not at risk of being eliminated by a sort of economic Darwinian selection. EE is a discipline that began in 1947 to train new entrepreneurs to rebuild world economies after the war and received increasing attention during the 1980s, when universities began offering courses to train future entrepreneurs [10][11] and create entrepreneurial research in the U.S. and Europe and then also in Asia [12].

International markets are prone to unpredictable events that can negatively influence a business, be they political, financial, environmental, technological, health-related or cultural. These can significantly affect consumer behavior, reducing the enterprise’s earnings [13][14][15][16][17][18][19], but we cannot adopt a fatalistic view of the economy, whereby we renounce the responsibility to prevent similar, unexpected events or, at least, to buffer their negative consequences on markets and economic activity. Following a liberal logic, especially after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the conflict between capitalist and communist countries, many entrepreneurs followed an aggressive business strategy based on saving resources and maximizing profits without considering workers’ rights, ecosystem balance or community needs [20][21][22][23]. This has impaired societies and the environment. For example, an entrepreneur who is entirely oriented toward profit maximization is not motivated to create a bond with the area where the enterprise operates; instead, they exploit the community’s workforce, raw materials or strategic position [24], and the capital generated is sent elsewhere, leaving the community that invested in this activity impoverished. Sometimes, the environment in which these communities live become polluted, and they suffer socio-economic distress [25][26][27]. In contrast, some projects offer an alternative entrepreneurial model based not only on economics, but also on innovative strategies and social aspects of the area in which they operate [28][29][30][31], also involving some integrated models of the stakeholder theory [32]. An entrepreneurial organization cannot consider itself to be an isolated institution, considering that it has a precise community context, even if it operates across different regions [33]. This aggressive and hypercompetitive strategy does not consider the importance of cooperation [34][35], which requires a coordinated approach, even in Entrepreneurship, where different institutions and organizations have a functional approach in order to reach a common goal. The approach of cooperativeness first emerged at the end of the 1980s [36], and there are some interesting studies concerning this approach [37][38][39]. We considered the importance of sensibility for environmental responsibility where an enterprise, even a small business, adopts an approach aiming to reduce the impact of its activity in terms of pollution or territorial alteration. In this case, we cite ecological intelligence [40] and community psychology [41][42], both of which must be considered so as to improve entrepreneurial performance. Future entrepreneurs must also be trained to consider these factors, as well as the social impact in terms of community wellness, including terms of employment, social cohesion, a sense of community and community empowerment [43][44][45]. It is not just an ethical question because an enterprise that acts responsibly will be appreciated by the community, which may lead to stronger partnerships [3][5][25][28][37].

2. Discussion

A quick database search for entrepreneurial education “AND” resilience “OR” social impact “OR” sustainability produced many records, with a total of just under 1000 on SCOPUS. Considering these keywords together because they are often considered independently. For example, an enterprise that focuses on societal change alone may neglect the environmental aspects, as was observed during a Boolean search of entrepreneurial education “AND” resilience “OR” social change “AND NOT” sustainability and vice versa when social change OR resilience was excluded. This trend of neglecting certain aspects is often encouraged, especially for ideological reasons. This was verified in some districts that refused to shut down their industrial structures because they feared the loss of jobs [6][11][46][47][48]. Despite this, innovations in technology are now making possible an effective industrial conversion that saves jobs and worker identities and preserves a sense of community as well as the environment [26][49][50][51][52][53]. From this point of view, entrepreneurial resilience must be considered as the result of different components. Mutual interaction reinforces the organization, in contrast to the traditional entrepreneurial philosophy in which a firm must maximize earnings to avoid failure [4][5][15][19], act as an individual [21][22][54][55] and avoid cooperation [56][46][57][58][59][60][61][62].

Recently, COVID-19 has exposed the illusion of medical and institutional invulnerability in the most privileged countries as social disparity, individualism, mental problems, economic instability and social injustice have been exacerbated. Consequently, humankind has had to rediscover the values of honesty, generosity, courage and foresight. The rejection of neo-liberal management provides the possibility of understanding the interdependence between world and market events [63][64][65][66][67][68][69][70][71]; adopting this mode of entrepreneurship, we will live in a better place—one in which an organization gains trust from the community and the entrepreneurial ecosystem in which it operates and receives help in return [6][36].

In the future, Entrepreneurship Education will have to negotiate some fundamental strategic challenges, such as training new entrepreneurs to use innovative strategies based on the skilled use of technology [29][51]; promoting managerial competences [72][73][74] to consider social [25][27][28][29][30][31][33][40][75] and environmental aspects [3][76][75]; and using electronic communication to facilitate learning [51]. EE has to adapt to different economic areas, including developing countries such as China, which is a complex and populous country with a high level of economic activity, consumption and pollution [77][78][79], but also in countries currently managing their economic transition [75][80][81]. There is a need for entrepreneurs to use wisdom in management strategies despite their fear of failure [33][81] and the risk of losing profits. [4][5][25][30]. A sustainable entrepreneurial strategy can assist in sectors such as “slow food” or agriculture [61][78], but also in those that have slow growth, and can provide a level of stability that can help them to resist a crisis [4][5][18][26][33][56]. The stakeholder theory underlines how important an ethical approach is for management, not only for business interest, but also for an interdependent socio-economic network, especially during world crises such as pandemics [9][19][68]. With this work, we state the urgent need for a “wealthy” entrepreneurial ecosystem [6][69].

Perhaps it is too early to define a precise research line due to the significant dispersion among authors’ contributions in this area, but we are fairly certain that it is a promising and growing topic for future research, especially after the end of the pandemic, as there will be a clear need to rebuild and re-organize interactions among people, organizations and communities, starting with the resilient organizations that survive the crisis.

It is tempting and easier to employ a reductive approach and focus on just one or two objectives when starting a business. This focus could just be to make money while neglecting civil rights and exploiting the environment, creating social distress and pollution as a result. Furthermore, it is important to underline, in this case, the relevance of the stakeholder theory, in which a responsible act performed by a restricted group of people encourages collective action to improve the world within and outside of an institutional framework [7][82][83]. We can also set a double objective, combining economic and social goals, economic and green goals, or social and green goals, while neglecting the third aspect. Even if the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is sometimes considered to be an incomplete criterion to evaluate a country’s economic performance [15], the World Bank (N.H., U.S.A.) shows that the annual growth of GDP for all countries in the world and—with the exception of China, a large country experiencing continuous growth—of most economic superpowers is decreasing, and we hypothesize that the current economic strategy, based primarily on an individualistic short-term planning strategy, should be reconsidered [55]. These approaches are often encouraged by ideology, but this can be a superficial approach that does not appreciate the entrepreneurial ecosystem complexity. In this case, the enterprise will fail, lose its resilience and collapse because it will not have a functional, long-term strategy. There is a need for entrepreneurial education to avoid the superficial, short-sighted approach. In this case, it is important to consider recent contributions from Nobel Prize researchers, which encourage the consideration of emotional triggers in economic behaviors [84][85], restructuring a dysfunctional belief about economic–rational infallibility.

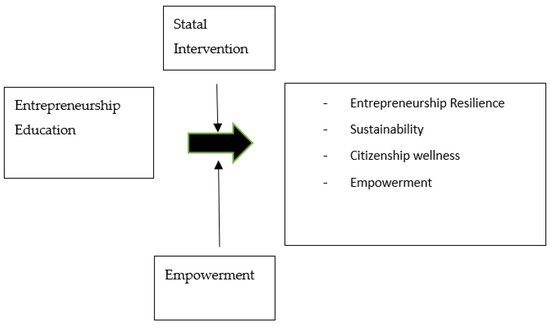

In line with the Community Psychology Paradigm [43][44][45], Entrepreneurship Education could reinforce concern for Sustainability and Social Impacts with regard to the territory, developing a sense of empowerment among citizens and Entrepreneurial Organizations, which could foster a functional attitude with a spontaneous initiative and/or through Institutional Intervention provided by the Government, which could encourage people, services and communities to adopt social functions, as represented in Figure 1. It suggests that organizational change for entrepreneurs comes from the top, via direct Statal–Institutional intervention, combined with change at the bottom. This requires the modification of the personal attitudes of entrepreneurs so that they are not just led by Institutions, but so that they also have a genuine, intrinsic motivation for creating a business organization that has a social function. Entrepreneurs should also be well informed about the interdependence of these worlds and their events and actions. [7][25][28][31]

Figure 1. Representation of positive factors for Sustainability and Organizational Resilience.

The empowerment of a community could be considered in this case both as a result of and a positive contributor to providing resilience, wellness and sustainability within communities [21][86][87]. In the future, we hope to use similar instruments for cluster mapping, such as SciMAT, CitNetExplorer and Sci2Tool [88][89][90] and databases such as SSCI [91] or EBSCO, following the example of other papers [92], with a different approach regarding co-occurrence and co-citations.

References

- Diaz, C.M.G.; Sanchez, G.A.C. Analysis of the Financial Intermadiation on the stage of the XX and XXI Centuries Crisis. Sophia-Educ. 2011, 7, 106–128.

- Mehediyev, A. The oil factor in the history of Azerbaijan. Vopr. Istor. 2018, 10, 138–144.

- Krehebiel, T.C.; Gorman, R.F.; Erkson, O.H.; Louks, O.L.; Johnson, P.C. Advancing ecology and economics through a business-science synthesis. Ecol. Econ. 1999, 14, 183–186.

- Liebenau, J.; Alleman, J. Network resilience and its regulatory inhibitors. Glob. Econ. Digit. Soc. 2004, 379–392.

- Rose, A.; Liao, S.Y. Modeling regional economic resilience to disasters: A computable general equilibrium analysis of water service disruptions. J. Reg. Financ. 2004, 45, 75–112.

- Geng, Y.; Cote, R. Diversity in industrial ecosystems. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2007, 14, 329–335.

- Santoro, G.; Bertoldi, G.; Giachino, C.; Candelo, E. Exploring the relationship between entrepreneurial resilience and success: The moderating role of stakeholders’ engagement. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 119, 142–150.

- Renko, M.; Bullough, A.; Saeed, S. How do Resilience and Self-Efficacy relate to entrepreneurial intentions in countries with varying degrees of fragility? A six-country study. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2021, 39, 130–156.

- Zighan, S.; Abualqumboz, M.; Dwaikat, N.; Alkalha, Z. The role of Entrepreneurial orientation in developing SMEs resilience capabilities throught COVID-19. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2021.

- Pittaway, L.; Cope, J. Entrepreneurship education: A systematic review of the evidence. Int. Small Bus. J. 2007, 25, 479–510.

- Mascarenhas, C.; Marques, C.; Galvão, A.R.; Santos, G. Entrepreneurial university: Towards a better understanding of past trends and future directions. J. Enterprising Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2017, 11, 316–338.

- Wu, Y.C.J.; Wu, T. A decade of entrepreneurship education in the Asia Pacific for future directions in theory and practice. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 1333–1350.

- Girard, S.; Agundez, J.A.P. The effects of the oyster mortality crisis on the economics of the shellfish farming sector: Preliminary review and prospects from a case study in Marennes-Oleron Bay (France). Mar. Policy 2014, 48, 142–151.

- Park-Barjort, R.R. Samsung: An original case of knowledge transfer in economic organizations. Enterp. Hist. 2014, 75, 91–101.

- Cerrato, D.; Alessandri, T.; Depperu, D. Economic crisis, acquisition and Firm Performance. Long Range Plan. 2016, 42, 171–185.

- Ulgen, F. Samsung: Financial development, economic crises and emerging market economies Financial Development. In Economic Crises and Emerging Market Economies; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 1–244.

- Angel, K.; Menendez-Plans, C.; Orgaz Guerrero, N. Risk management: Comparative analysis of systematic risk and effect of the financial crisis on US tourism industry: Panel data research. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 1920–1938.

- Hyz, A. SME Finance and the Economic Crisis: The Case of Greece; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 1–119.

- Golubeva, O. Firms’ performance during the COVID-19 outbreak: International evidence from 13 countries. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2021, 21, 1011–1027.

- Michalski, T. Radical innovation through corporate entrepreneurship from a Competence-Based Strategic Management perspective. Int. J. Manag. Pract. 2006, 2, 22–41.

- Mahato, R.V.; Ahluwalia, S.; Walsh, S.T. The diminishing effect of VC reputation: Is it hypercompetition? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 133, 229–237.

- Vaisman, E.D.; Podshivalova, M.V. Assessment of small industry resistance to the hypercompetition threats in regions. Econ. Reg. 2018, 14, 1232–1245.

- Cooke, P. Economic globalisation and its future challenges for regional development. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2003, 26, 401–420.

- Bellandi, M.; Carloffi, A. District internationalisation and trans-local development. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2008, 20, 517–532.

- Smith, D.C.; James, C.D.; Griffiths, M.A. Co-brand partnerships making space for the next black girl: Backlash in social justice branding. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 2314–2326.

- Surya, B.; Suriani, F.; Menne, F.; Abubakar, H.; Idris, M.; Rasyidi, E.S.; Remmang, H. Community empowerment and utilization of renewable energy: Entrepreneurial perspective for community resilience based on sustainable management of slum settlements in Makassar city, Indonesia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3178.

- Uduji, J.I.; Okolo-Obasi, E.N.; Asongu, S.A. Oil extraction in Nigeria’s Ogoniland: The role of corporate social responsibility in averting a resurgence of violence. Resour. Policy 2021, 70, 101927.

- Pless, N.M.; Maak, T.; Stahl, G.K. Promoting corporate social responsibility and sustainable development through management development: What can be learned from international service learning programs? Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 51, 873–903.

- Urbano, D.; Guerrero, M.; Ferreira, J.J.; Fernandes, C.I. New technology entrepreneurship initiatives: Which strategic orientations and environmental conditions matter in the new socio-economic landscape? J. Technol. Transf. 2019, 44, 1577–1602.

- Eggers, F. Masters of disasters? Challenges and opportunities for SMEs in times of crisis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 199–208.

- Sirine, H.; Andadari, R.K.; Suharti, L. Social Engagement Network and Corporate Social Entrepreneurship in Sido Muncul Company, Indonesia. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 885–892.

- Argandoña, A. El bien Común; IESE Business School, Universidad de Navarra: Barcelona, Spain, 2011.

- Naradda Gamage, S.K.; Ekanayake, E.M.S.; Abeyrathne, G.A.K.N.J.; Prasanna, R.P.I.R.; Jayasundara, J.S.M.B.; Rayapakshe, P.S.K. A review of global challenges and survival strategies of small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Economies 2020, 8, 79.

- Chuah, S.H.; Hoffmann, R.; Ramasamy, B.; Tan, J.H.W. Is there a spirit of Overseas Chinese Capitalism? Small Bus. Econ. 2016, 47, 1095–1118.

- Crick, J.M. Incorporating coopetition into the entrepreneurial marketing literature: Directions for future research. J. Res. Mark. Entrep. 2019, 21, 19–36.

- Carsrud, A.L.; Olm, K.W.; Thomas, J.B. Predicting entrepreneurial success: Effects of multi-dimensional achievement motivation, levels of ownership, and cooperative relationships. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 1989, 1, 237–244.

- Levine, S.S.; Preitula, M.J. Open collaboration for innovation: Principles and performance. Organ. Sci. 2014, 25, 1414–1433.

- Kimuli, S.N.L.; Orobia, L.; Sabi, H.M. Sustainability intention: Mediator of sustainability behavioral control and sustainable entrepreneurship. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 2, 81–95.

- Srikaliman, S.; Wardana, L.W.; Ambarwati, D.; Sholhin, U.; Shobrin, L.A.; Fajarah, N.; Wibowo, A. DO Creativity and Intellectual Capital matter for SME sustainability? The role of competitive advantage. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 397–408.

- Goleman, D. Ecological Intelligence: The Hidden Impacts of What We Buy; Broadway Books: New York, NY, USA, 2010.

- Rappaport, J. In Praise of Paradox. A Social Policy of Empowerment over Prevention. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1981, 1, 1–25.

- Francescato, D.; Tomai, M.; Solimeno, A. Lavorare e Decidere Meglio in Organizzazioni Empowering ed Empowered; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2008.

- Mulyono, S.E.; Sutarto, J.; Malik, A.; Loretha, A.F. Community Empowerment in Entrepreneurship development based on local potential. Int. J. Innov. Creat. Chang. 2020, 11, 271–283.

- Rocha, H.; Kunc, M.; Audretsch, D.B. Clustersm Economic Performance and social cohesion: A system dynamics approach. Reg. Stud. 2020, 54, 1098–1111.

- Rojikinnor, R.; Gani, A.J.A.; Saleh, H.; Amin, F. Empowerment throught good Governance and Public Service Quality. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 491–497.

- Arshad, R.; Noor, A.H.R.; Yahya, A. Human Capital and Islamic-Based Social Impact Model: Small Enterprise Perspective. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 31, 510–519.

- Zdonek, I.; Mularczyk, A.; Polock, G. The idea of corporate social responsibility in the opinion of future managers—Comparative research between Poland and Georgia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7045.

- Castro, M.P.; Scheede, C.R.; Zermeno, M.G.G. The Impact of Higher Education on Entrepreneurship and the Innovation Ecosystem: A Case Study in Mexico. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5597.

- Sandoval, F.; Garcia, F. Por La Senda De Un Futuro Sustentable. Propuestas Y Acciones Con Responsabilidad Social. In Sustainability in University Education: A Challenge for a Comprehensive Education in the Faculty of Economy and Business of the University of Chile; Universidad de Santiago de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2016; pp. 557–568.

- Ares, J. Estimating pesticide environmental risk scores with land use data and fugacity equilibrium models in Misiones, Argentina. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2004, 103, 45–58.

- Calvo, S.; Lyon, F.; Morales, A.; Wade, J. Educating at Scale for Sustainable Development and Social Enterprise Growth: The Impact of Online Learning and a Massive Open Online Course (MOOC). Sustainability 2020, 12, 3247.

- Bernard-Hernandez, P.; Ramirez, M.; Mosquera-Montoya, M. Formal rules and its role in centralised-diffusion systems: A study of small-scale producers of oil palm in Colombia. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 83, 215–225.

- Ajayi, C.O. The effect of Microcredit on rural household livelihood: Evidence from women micro entrepreneurs in Oyo State, Nigeria. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural. Dev. 2016, 16, 29–36.

- McKenna, B. Wisdom, Ethics and the Postmodern Organisation. In Handbook on the Knowledge Economy; Rooney, D., Hearn, G., Ninan, A., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Gloucestershire, UK, 2005; pp. 37–53.

- Burrows, S. Precarious work, neo-liberalism and young people’s experiences of employment in the Illawarra region. Econ. Labour Relat. Rev. 2013, 24, 380–396.

- Grant, J.H. Advances and Challenges in Strategic Management. Int. J. Bus. 2007, 12, 11–31.

- Iyer, V.G. Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) Process for Green Materials and Environmental Engineering Systems towards Sustainable Development-Business Excellence Achievements. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Green Materials and Environmental Engineering (GMEE), Beijing, China, 28–29 October 2018.

- Sedita, S.R.; Ozeki, T. Path renewal dynamics in the Kyoto kimono cluster: How to revitalize cultural heritage through digitalization. Eur. Panning Stud. 2021.

- Salameh, M.T.B.; Alraggad, M.; Harasheh, S.T. The water crisis and the conflict in the Middle East. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2021, 7, 69.

- Stroud, D.; Fairbrother, P.; Evans, C.; Blake, J. Skill development in the transition to a ‘green economy’: A ‘varieties of capitalism’ analysis. Econ. Labour Relat. Rev. 2014, 25, 10–27.

- DeLind, L.B. Where have all the houses (among other things) gone? Some critical reflections on urban agriculture. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2015, 30, 3–7.

- Freeman, R.E. Business ethics at the Millenium. Glob. Ethics Bus. 2000, 10, 169–180.

- Billet, A.; Dufays, S.; Friedel, S.; Staessens, M. The resilience of the cooperative model: How do cooperatives deal with the COVID-19 crisis? Strateg. Chang. 2021, 30, 99–108.

- Hayter, C.S. Toward a strategic view of higher education social responsibilities: A dynamic capabilities approach. Strateg. Organ. 2018, 16, 12–34.

- Parris, D.L.; McInnis-Bowers, C. Business Not as Usual: Developing Socially Conscious Entrepreneurs and Intrapreneurs. J. Manag. Educ. 2017, 41, 687–726.

- Yildrim, K.; Onder, M. Collaborative Role of Metropolitan Municipalities in Local Climate Protection Governance Strategies: The Case of Turkish Metropolitan Cities. J. Environ. Assestment Policy Manag. 2019, 21, 1950006.

- Yin, R.; Yin, G.; Li, L. Assessing China’s ecological restoration programs: What’s been done and what remains to be done? Integr. Assess. China’s Ecol. Restor. Programs 2009, 45, 442–453.

- Chocholab, P.; Tapachai, N. Organizational resilience of SMEs in the Czech Republic: An exploratory analysis. In Proceedings of the ICABR 2015: X. International Conference On Applied Business Research, Madrid, Spain, 14–18 September 2015; pp. 395–417.

- Larsson, M.; Milestad, R.; Hahn, T.; Von Oelreich, J. The resilience of a sustainability entrepreneur in the Swedish food system. Sustainability 2016, 8, 550.

- Notman, O. The value of short-term training for Russian managers in the context of economic crisis. In Proceedings of the 10th International Days of Statistics and Economics, Prague, Czech Republic, 8–10 September 2016; pp. 1344–1352.

- Ahmad, M. Does underconfidence matter in short-term and long-term investment decisions? Evidence from an emerging market. Manag. Decis. 2021, 59, 692–709.

- Sanchez-Hernandez, M.I.; Gallardo-Vazquez, D.; Pajuelo-Moreno, M.L. University Social Responsibility: A Modelling Framework for Student Base Analysis. In Proceedings of the 9th International Technology, Education and Development Conference, Madrid, Spain, 2–4 March 2015; pp. 2523–2530.

- Starnawska, M. Determining Critical Issues In Social Entrepreneurship Education. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference Innovation Management, Entrepreneurship And Sustainability (IMES 2018), Prague, Czech Republic, 31 May–1 June 2018; pp. 1014–1024.

- Sassenrath, G.F.; Halloram, J.M.; Archer, D.; Raper, R.L.; Hendrickson, J.; Vadas, P.; Hanson, J. Drivers Impacting the Adoption of Sustainable Agricultural Management Practices and Production Systems of the Northeast and Southeast United States. J. Sustain. Agric. 2010, 34, 680–702.

- Bednar, P.; Danko, L.; Smekalova, L. Coworking spaces and creative communities: Making resilient coworking spaces through knowledge sharing and collective learning. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2021.

- Badulescu, D.; Badulescu, A.; Bac, D.P.; Saveanu, T.; Florea, A.; Perticas, D. Education and Sustainable Development: From theoretical interest to specific behaviours. J. Environ. Prot. Ecol. 2017, 18, 1698–1705.

- Markopoulos, E.; Staggl, A.; Gann, E.L.; Vanharanta, H. Beyond Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): Democratizing CSR Towards Environmental, Social and Governance Compliance. In International Conference on Applied Human Factors and Ergonomics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 276, pp. 94–103.

- Hosseinina, G.; Ramezani, A. Factors Influencing Sustainable Entrepreneurship in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Iran: A Case Study of Food Industry. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1010.

- Deszy, S.; Miclaus, C.; Rizescu, N.; Nicu, M. Industrial sites and past pollution problems. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2004, 3, 861–869.

- Žebrytė, I.; Fonseca-Vasquez, M.; Hartley, R. Emerging economy entrepreneurs and open data: Decision-making for natural disaster resilience. J. Small Bus. Strategy 2019, 29, 36–46.

- Chlopecky, J.; Rolcikova, L.; Kratochvil, M. Decision making influence of some macroeconomic factors concerning prospective sales of silicon carbide. In Proceedings of the 15th International Multidisciplinary Scientific Geoconference SGEM 2015, Albena, Bulgaria, 18–24 June 2015; pp. 171–178.

- Al Mamun, A.; Ibrahim, M.D.; Bin Yusoff, M.N.H.; Fazal, S.A. Entrepreneurial Leadership, Performance, and Sustainability of Micro-Enterprises in Malaysia. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1591.

- Rousseau, J.F. Does carbon finance make a sustainable difference? Hydropower expansion and livelihood trade-offs in the Red River valley, Yunnan Province, China. Singap. J. Trop. Geogr. 2017, 38, 90–107.

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Heuristics and Biases: The Psychology of Intuitive Judgement; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002.

- Tahler, R.H. Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics.; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2015.

- Matzembacher, D.E.; Raudsaar, M.; De Barcellos, M.D.; Mets, T. Business models’ innovations to overcome hybridity-related tensions in sustainable entrepreneurship. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4503.

- Anderson, O. Education provides a foundation for Community Empowerment IEEE Smart Village Programs Teach Residents Job, Technical and Business, Skills. IEE Syst. Man Cybern. Mag. 2019, 5, 42–46.

- Sci2 Team. Science of Science (Sci2) Tool; Indiana University (USA) and SciTech Strategies: Albuquerque, NM, USA, 2009.

- Cobo, M.J.; Lòpez-Herrera, A.G.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Herrera, F. SciMat: A new Science mapping analysis software tool. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2012, 63, 1609–1630.

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. CitNetExplorer: A new software tool for analyzing and visualizing citation networks. J. Informetr. 2014, 8, 802–823.

- Torres-Pruñonosa, J.; Plaza-Navas, M.A.; Dìez-Martinf, F.; Beltran-Cangròs, A. The Intellectual Structure of Social and Sustainable Public Procurement Research: A Co-Citation Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 774.

- Torres-Prunonosa, J.; Plaza-Navas, M.A.; Diez-Martin, C. The source of Knowledge of the Economic and Social Value in Sport Industry Research: A co-citation Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 629951.

More

Information

Subjects:

Anthropology

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

916

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

19 Jan 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No