Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Maria Grano | + 1900 word(s) | 1900 | 2022-01-11 04:05:42 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | Meta information modification | 1900 | 2022-01-19 02:14:35 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Grano, M. Irisin and Secondary Osteoporosis. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18432 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Grano M. Irisin and Secondary Osteoporosis. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18432. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Grano, Maria. "Irisin and Secondary Osteoporosis" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18432 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Grano, M. (2022, January 18). Irisin and Secondary Osteoporosis. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/18432

Grano, Maria. "Irisin and Secondary Osteoporosis." Encyclopedia. Web. 18 January, 2022.

Copy Citation

Osteoporosis is a progressive multifactorial skeletal disorder characterized by the deterioration of bone microarchitecture and increased susceptibility to fracture risk.

irisin

osteoporosis

hyperparathyroidism

Prader–Willi syndrome

1. Introduction

Osteoporosis and sarcopenia are the most common musculoskeletal disorders in the elderly; however, they can also affect young people with metabolic disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, cancer diseases, and astronauts during space missions due to weightlessness. Osteoporosis and sarcopenia represent a dangerous “duet” with a significant social relevance for the great socio-health impact of the consequent fractures. Pharmacologically, while some measures to treat sarcopenia are beneficial for bone health, the treatment of osteoporosis does not always reflect positively on muscles. Regular exercise is one of the proven non-pharmacological strategies to prevent bone fragility and sarcopenia. However, not all individuals are in a condition to perform regular physical activity; therefore, the identification of exercise-mimicking molecules represents a resource to prevent and/or treat both diseases.

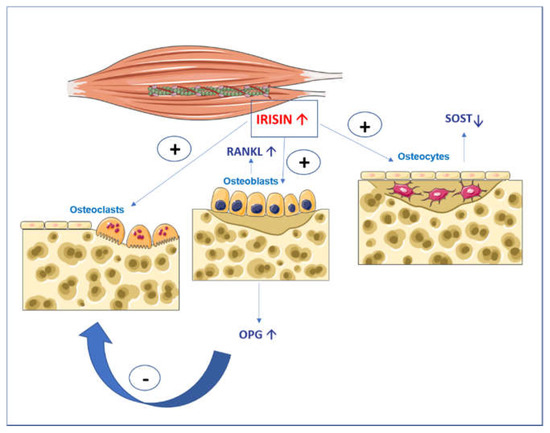

Myokine irisin is a protein secreted into the blood by cleavage of membrane protein 5 (FNDC5) after a skeletal muscle contraction under the control of coactivator 1-alpha (PGC1alpha) [1]. Early studies by Bostrom et al. showed the effect of irisin in activating the trans-differentiation of white adipose tissue into brown tissue. Irisin was found to play important roles in metabolic disorders, Alzheimer’s disease, brain function, and bone metabolism [2][3][4]. Several studies demonstrated that irisin influences bone cells [5][6][7][8][9][10][11]. Specifically, it was shown that irisin stimulates osteoblast differentiation and activity, through the upregulation of transcription factors and matrix proteins such as the Activating Transcription Factor 4 (Atf4) and Collagen I. In addition, irisin directly affects osteocytes by increasing their viability. In parallel, irisin has a dual action on osteoclasts: an indirect action through the increased expression of Osteoprotegerin (OPG) by osteoblasts [6][9] and a direct action in stimulating osteoclastogenesis of osteoclast precursors treated continuously with 10 ng/mL of recombinant irisin (rec-irisin) (Figure 1) [10].

Figure 1. Graphical illustration of the action of irisin on bone cells. Irisin increases osteoblast differentiation and activity and affects osteocytes by increasing their viability and inhibiting the expression of Sost, the gene coding for sclerostin. Irisin has a double action on osteoclasts: an indirect action through the increase in osteoprotegerin (OPG) expression in osteoblasts that block the receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-Β ligand (RANKL), and in parallel, a direct action by stimulating the differentiation of osteoclast precursors.

However, the same authors observed that a higher dose (20 ng/mL) increased the number of osteoclasts significantly less than the 10 ng/mL dose, and doses of irisin equal to or greater than 100 ng/mL decreased osteoclastogenesis [10]. Furthermore, Zhang and colleagues [12] treated pre-osteoclastic RAW264.7 cells with rec-irisin for 3 days and observed a significant reduction in the mRNA levels of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFATc1), and cathepsin K (CatK) [12]. In addition, the difference observed in vivo between the study by Estell et al. [10] and the study by Zhang et al. [12], may be due to the duration of irisin treatment, i.e., short duration (7 days) promoting osteoclastogenesis [10], and chronic treatment (2 months) [12] inhibiting osteoclastogenesis through the increased activity of the Mck promoter of Fndc5.

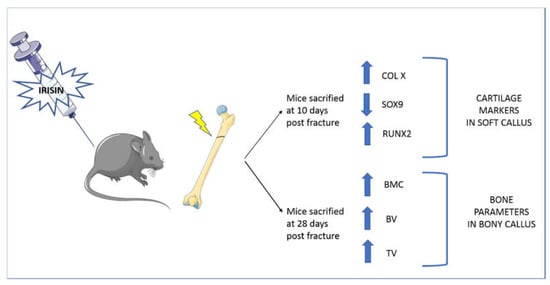

Therefore, it was hypothesized that irisin concentrations, as well as frequency and duration of treatment, are responsible for the discrepancies observed in the different studies. Experiments conducted in vivo on young healthy mice show a positive effect of rec-irisin on cortical bone and its mechanical properties, improving some parameters such as cortical bone surface, tissue mineral density, cortical perimeter and polar moment of inertia, an index of resistance of long bone to torsional forces [8]. Follow-up studies on osteoporotic mouse models showed that treatment with rec-irisin prevented both cortical and trabecular bone mineral density (BMD) reduction in mice subjected to four weeks of unloading [9]. Furthermore, if irisin was administered after four weeks of unloading, when bone loss already occurred, cortical and trabecular BMD loss were reverted, indicating the potential of irisin to also treat osteoporosis [9]. In contrast with these results, Kim and colleagues showed that mice with a global deletion of the irisin precursor, FNDC5, were resistant to ovariectomy-induced bone loss through the inhibition of osteoclastic bone resorption and osteocytic osteolysis [11]. The authors also observed an increased expression of sclerostin, an inhibitor of bone formation, after 6 daily injections of 1 mg/kg of irisin [11]. In contrast, a reduction in sclerostin was observed by injecting unloaded mice with a 10 times lower dose, given weekly for 4 weeks [9]. Similar to the parathyroid hormone (PTH), which exerts both catabolic and anabolic effects on the skeleton depending on the administration regimen [13], it was hypothesized that a high dose of irisin could lead to bone catabolism [11], whereas a lower dose, given with intermittent pulses of irisin, as occurs during exercise, could have anabolic effects on bone [9]. To further explore this hypothesis, studies were conducted to evaluate the effects of irisin on osteocyte viability when it was administered at low doses and intermittently, as occurs during exercise. The results showed that the treatment of unloaded mice with 100 μg/kg weekly of rec-irisin for four weeks inhibited disuse-induced osteocytes apoptosis and reduced the number of empty lacunae compared to unloaded mice treated with a vehicle [14]. In vitro studies were conducted on osteocyte-like cell lines (Mlo-y4), demonstrating that irisin treatment increases osteocyte survival by upregulating Blc2/Bax ratio and preventing dexamethasone and hydrogen peroxide-induced caspase activation. Moreover, in vivo studies also showed an inhibition of caspase activation in the cortical bone of unloaded mice treated with rec-irisin [14]. Additionally, rec-irisin activated the MAP kinases, Erk1 and Erk2, and increased the expression of the transcription factor Atf4 through an Erk-dependent pathway in osteocytes [14]. These results revealed the basic mechanisms of irisin’s action on osteocytes; to increase their functions and exert antiapoptotic effects, confirming that mechanosensory cells in bone are sensitive to the exercise-mimetic myokine irisin [14]. Very recently, it was shown that the systemic administration of an intermittent, low dosage of irisin accelerates bone fracture healing in mice [15]. By examining the impact of irisin treatment after 10 and 28 days post fracture, we observed an accelerated shift of cartilage callus to bony callus, along with a modification of chondrocytes towards the hypertrophic phenotype, and an increase in callus volume and bone mineral content, indicating a more rapid mineralization without affecting trabecular architecture and bone remodeling (Figure 2) [15].

Figure 2. Systemic administration of recombinant irisin accelerates fracture healing in mice. Treatment with irisin administered at a low dose (100 μg/kg) and intermittently (once a week) increased X-type collagen expression in the cartilaginous callus at 10 days after fracture, indicating a more advanced stage of endochondral ossification of the callus during the early phase of fracture repair. Further evidence that irisin induced the transition of cartilaginous callus into osseous callus was provided by a reduction in SRY (sex-determining region Y)-box 9 (SOX9) and an increase in runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2). At 28 days after fracture, microCT analyses showed that total callus volume (TV), bone volume (BV), and bone mineral content (BMC) were increased in irisin-treated mice compared with controls.

In support of the importance of irisin in the human musculoskeletal system, observational studies have shown that circulating irisin levels correlate positively with parameters of healthy bone and muscle tissues [16][17]. Recently, we described a positive correlation between serum irisin and both femoral and vertebral bone mineral density in a population of elderly subjects [18]. Levels of the irisin precursor, FNDC5, in skeletal muscle of these subjects correlated positively with serum irisin levels and osteocalcin expression in bone biopsies, indicating a strong correlation between muscle and bone [18]. In the same study, we provided in vitro evidence demonstrating that treatment with rec-irisin in osteoblasts reduces the expression of p21, one of the effectors of the senescence process [18]. Therefore, these results suggest that this molecule could represent a viable therapeutic option to delay osteoporosis caused by senescence [19].

All these in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated the importance of irisin action on bone metabolism. Although some aspects remain to be elucidated, particularly the dose- and frequency-dependent effects of irisin in cell cultures and in mouse models, extensive clinical evidence is emerging in support of its physiological relevance for bone and its role in secondary osteoporosis. In parallel, new studies identify irisin as a possible serum prognostic marker of bone pathologies [20][21].

2. Irisin in Primary Hyperparathyroidism

Primary hyperparathyroidism (PHPT) is an endocrine disease characterized by elevated calcium and PTH levels [22]. Affected patients develop a decreased BMD, particularly at the cortical site of the distal radius [23]. Joint pain is a common symptom in patients with PHPT [24][25], who, over time, develop osteoarthritis and osteoporosis [26]. Less frequent manifestations include Achilles tendon rupture, and sacral insufficiency fractures [24]. Biomolecular studies revealed that chronic high levels of PTH stimulate osteoclastogenesis indirectly by acting on osteoblasts. Indeed, PTH-stimulated osteoblasts secrete nuclear factor receptor-κB ligand (RANKL) and release low levels of OPG [23]. Emerging preclinical data regarding the possible interaction between PHT and irisin showed that, although in opposite ways, both affect bone, muscle, and adipose tissue. Therefore, recent studies focused on the cellular interaction between these two hormones by evaluating the expression of the irisin precursor, FNDC5, in skeletal muscle cells treated with 1-34 PTH (Teriparatide). Palermo et al. demonstrated that both short-term (3 h) and long-term (6 days) treatment with PTH negatively regulates the FNDC5 gene and protein expression in myotubes by acting through the PTH receptor, which in turn activates the phosphorylation of Erk1/2, most likely increasing intracellular cAMP [17]. The study also showed that irisin treatment decreases PTH receptor expression in osteoblasts, suggesting that this myokine may exert its anabolic effect on bone not only by stimulating osteoblast formation and function, but also by reducing the action of PTH on these cells [17]. Furthermore, serum irisin levels were lower in postmenopausal women with PHPT compared with control subjects [17]. This finding supported the results of other previous clinical investigations showing that irisin was inversely related to PTH in postmenopausal women with low bone mass [27] and in hemodialysis patients [28]. It is known that physical activity can help reduce PTH secretion, particularly if the exercise is chronic rather than resistance exercise [29]. This is relevant to the disease, as a slight reduction in circulating PTH levels may be desirable in patients with PHPT.

3. Irisin in Prader-Willi Syndrome (PWS)

Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) is a rare genetic disorder that affects appetite, growth, the hormonal system, metabolism, cognitive function, and behavior. Most cases of PWS are attributed to a spontaneous genetic error that occurs due to a lack of gene expression in a specific part of the long arm of the paternal chromosome 15 [30]. The main mechanisms leading to the lack of gene expression responsible for Prader–Willi syndrome are interstitial deletion of the proximal long arm of chromosome 15 (del15q11-q13) (DEL15), maternal uniparental disomy of chromosome 15 (UPD15), and imprinting defects [31]. Patients with PWS show reduced muscle tone, short stature, incomplete sexual development, intellectual disability, peculiar behavior, poor nutrition, and initial failure to thrive, followed by hyperphagia and obesity in early childhood if eating is not controlled, multiple endocrine abnormalities, including growth hormone deficiency (GHD) and hypogonadism [32][33].

Notably, PWS patients also show bone defects. Children with PWS during puberty have normal bone mineral density (BMD) adjusted for reduced height [34][35][36], but in adolescence and adulthood, they show a decrease in total BMD and, in some cases, bone mineral content (BMC), because they have not reached bone mineral maturation; this is also due to pubertal delay/hypogonadism [37][38][39][40]. Consequently, osteoporosis is predominant in PWS individuals, who also have other orthopedic complications, worsened by weight gain, including scoliosis, kyphosis, hip dysplasia, flat feet, genu valgum, and fractures [39][41].

References

- Boström, P.; Wu, J.; Jedrychowski, M.P.; Korde, A.; Ye, L.; Lo, J.C.; Rasbach, K.A.; Boström, E.A.; Choi, J.H.; Long, J.Z.; et al. A PGC1-α-dependent myokine that drives brown-fat-like development of white fat and thermogenesis. Nature 2012, 481, 463–468.

- Eckardt, K.; Görgens, S.W.; Raschke, S.; Eckel, J. Myokines in insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2014, 57, 1087–1099.

- Kim, O.Y.; Song, J. The Role of Irisin in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 407.

- Peng, H.; Wang, Q.; Lou, T.; Qin, J.; Jung, S.; Shetty, V.; Li, F.; Wang, Y.; Feng, X.H.; Mitch, W.E.; et al. Myokine mediated muscle-kidney crosstalk suppresses metabolic reprogramming and fibrosis in damaged kidneys. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1493.

- Buccoliero, C.; Oranger, A.; Colaianni, G.; Pignataro, P.; Zerlotin, R.; Lovero, R.; Errede, M.; Grano, M. The effect of Irisin on bone cells in vivo and in vitro. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2021, 49, 477–484.

- Colucci, S.; Colaianni, G.; Brunetti, G.; Ferranti, F.; Mascetti, G.; Mori, G.; Grano, M. Irisin prevents microgravity-induced impairment of osteoblast differentiation in vitro during the space flight CRS-14 mission. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 10096–10106.

- Colaianni, G.; Cuscito, C.; Mongelli, T.; Oranger, A.; Mori, G.; Brunetti, G.; Colucci, S.; Cinti, S.; Grano, M. Irisin enhances osteoblast differentiation in vitro. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2014, 2014, 902186.

- Colaianni, G.; Cuscito, C.; Mongelli, T.; Pignataro, P.; Buccoliero, C.; Liu, P.; Lu, P.; Sartini, L.; Di Comite, M.; Mori, G.; et al. The myokine irisin increases cortical bone mass. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 12157–12162.

- Colaianni, G.; Mongelli, T.; Cuscito, C.; Pignataro, P.; Lippo, L.; Spiro, G.; Notarnicola, A.; Severi, I.; Passeri, G.; Mori, G.; et al. Irisin prevents and restores bone loss and muscle atrophy in hind-limb suspended mice. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2811.

- Estell, E.G.; Le, P.T.; Vegting, Y.; Kim, H.; Wrann, C.; Bouxsein, M.L.; Nagano, K.; Baron, R.; Spiegelman, B.M.; Rosen, C.J. Irisin directly stimulates osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption in vitro and in vivo. Elife 2020, 9, e58172.

- Kim, H.; Wrann, C.D.; Jedrychowski, M.; Vidoni, S.; Kitase, Y.; Nagano, K.; Zhou, C.; Chou, J.; Parkman, V.A.; Novick, S.J.; et al. Irisin Mediates Effects on Bone and Fat via αV Integrin Receptors. Cell 2018, 175, 1756–1768.e1717.

- Zhang, J.; Valverde, P.; Zhu, X.; Murray, D.; Wu, Y.; Yu, L.; Jiang, H.; Dard, M.M.; Huang, J.; Xu, Z.; et al. Exercise-induced irisin in bone and systemic irisin administration reveal new regulatory mechanisms of bone metabolism. Bone Res. 2017, 5, 16056.

- Silva, B.C.; Bilezikian, J.P. Parathyroid hormone: Anabolic and catabolic actions on the skeleton. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2015, 22, 41–50.

- Storlino, G.; Colaianni, G.; Sanesi, L.; Lippo, L.; Brunetti, G.; Errede, M.; Colucci, S.; Passeri, G.; Grano, M. Irisin Prevents Disuse-Induced Osteocyte Apoptosis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2020, 35, 766–775.

- Colucci, S.C.; Buccoliero, C.; Sanesi, L.; Errede, M.; Colaianni, G.; Annese, T.; Khan, M.P.; Zerlotin, R.; Dicarlo, M.; Schipani, E.; et al. Systemic Administration of Recombinant Irisin Accelerates Fracture Healing in Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10863.

- Faienza, M.F.; Brunetti, G.; Sanesi, L.; Colaianni, G.; Celi, M.; Piacente, L.; D’Amato, G.; Schipani, E.; Colucci, S.; Grano, M. High irisin levels are associated with better glycemic control and bone health in children with Type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2018, 141, 10–17.

- Palermo, A.; Sanesi, L.; Colaianni, G.; Tabacco, G.; Naciu, A.M.; Cesareo, R.; Pedone, C.; Lelli, D.; Brunetti, G.; Mori, G.; et al. A Novel Interplay Between Irisin and PTH: From Basic Studies to Clinical Evidence in Hyperparathyroidism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 104, 3088–3096.

- Colaianni, G.; Errede, M.; Sanesi, L.; Notarnicola, A.; Celi, M.; Zerlotin, R.; Storlino, G.; Pignataro, P.; Oranger, A.; Pesce, V.; et al. Irisin Correlates Positively With BMD in a Cohort of Older Adult Patients and Downregulates the Senescent Marker p21 in Osteoblasts. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2021, 36, 305–314.

- Farr, J.N.; Khosla, S. Cellular senescence in bone. Bone 2019, 121, 121–133.

- Yan, J.; Liu, H.J.; Guo, W.C.; Yang, J. Low serum concentrations of Irisin are associated with increased risk of hip fracture in Chinese older women. Joint. Bone Spine 2018, 85, 353–358.

- Mao, Y.; Xu, W.; Xie, Z.; Dong, Q. Association of Irisin and CRP Levels with the Radiographic Severity of Knee Osteoarthritis. Genet. Test. Mol. Biomark. 2016, 20, 86–89.

- Silva, B.C.; Cusano, N.E.; Bilezikian, J.P. Primary hyperparathyroidism. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 32, 593–607.

- Silva, B.C.; Costa, A.G.; Cusano, N.E.; Kousteni, S.; Bilezikian, J.P. Catabolic and anabolic actions of parathyroid hormone on the skeleton. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2011, 34, 801–810.

- Pappu, R.; Jabbour, S.A.; Reginato, A.M.; Reginato, A.J. Musculoskeletal manifestations of primary hyperparathyroidism. Clin. Rheumatol. 2016, 35, 3081–3087.

- Murray, S.E.; Pathak, P.R.; Pontes, D.S.; Schneider, D.F.; Schaefer, S.C.; Chen, H.; Sippel, R.S. Timing of symptom improvement after parathyroidectomy for primary hyperparathyroidism. Surgery 2013, 154, 1463–1469.

- Chiodini, I.; Cairoli, E.; Palmieri, S.; Pepe, J.; Walker, M.D. Non classical complications of primary hyperparathyroidism. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 32, 805–820.

- Anastasilakis, A.D.; Polyzos, S.A.; Makras, P.; Gkiomisi, A.; Bisbinas, I.; Katsarou, A.; Filippaios, A.; Mantzoros, C.S. Circulating irisin is associated with osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women with low bone mass but is not affected by either teriparatide or denosumab treatment for 3 months. Osteoporos. Int. 2014, 25, 1633–1642.

- He, L.; He, W.Y.; A, L.T.; Yang, W.L.; Zhang, A.H. Lower Serum Irisin Levels Are Associated with Increased Vascular Calcification in Hemodialysis Patients. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2018, 43, 287–295.

- Lombardi, G.; Ziemann, E.; Banfi, G.; Corbetta, S. Physical Activity-Dependent Regulation of Parathyroid Hormone and Calcium-Phosphorous Metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5388.

- Tauber, M.; Diene, G. Prader-Willi syndrome: Hormone therapies. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2021, 181, 351–367.

- Butler, M.G.; Hartin, S.N.; Hossain, W.A.; Manzardo, A.M.; Kimonis, V.; Dykens, E.; Gold, J.A.; Kim, S.J.; Weisensel, N.; Tamura, R.; et al. Molecular genetic classification in Prader-Willi syndrome: A multisite cohort study. J. Med. Genet. 2019, 56, 149–153.

- Angulo, M.A.; Butler, M.G.; Cataletto, M.E. Prader-Willi syndrome: A review of clinical, genetic, and endocrine findings. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2015, 38, 1249–1263.

- Driscoll, D.J.; Miller, J.L.; Schwartz, S.; Cassidy, S.B. Prader-Willi Syndrome. In GeneReviews(®); Adam, M.P., Ardinger, H.H., Pagon, R.A., Wallace, S.E., Bean, L.J.H., Mirzaa, G., Amemiya, A., Eds.; University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 2012.

- De Lind van Wijngaarden, R.F.; Festen, D.A.; Otten, B.J.; van Mil, E.G.; Rotteveel, J.; Odink, R.J.; van Leeuwen, M.; Haring, D.A.; Bocca, G.; Mieke Houdijk, E.C.; et al. Bone mineral density and effects of growth hormone treatment in prepubertal children with Prader-Willi syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94, 3763–3771.

- Edouard, T.; Deal, C.; Van Vliet, G.; Gaulin, N.; Moreau, A.; Rauch, F.; Alos, N. Muscle-bone characteristics in children with Prader-Willi syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 97, E275–E281.

- Van Mil, E.G.; Westerterp, K.R.; Gerver, W.J.; Van Marken Lichtenbelt, W.D.; Kester, A.D.; Saris, W.H. Body composition in Prader-Willi syndrome compared with nonsyndromal obesity: Relationship to physical activity and growth hormone function. J. Pediatr. 2001, 139, 708–714.

- Vestergaard, P.; Kristensen, K.; Bruun, J.M.; Østergaard, J.R.; Heickendorff, L.; Mosekilde, L.; Richelsen, B. Reduced bone mineral density and increased bone turnover in Prader-Willi syndrome compared with controls matched for sex and body mass index—A cross-sectional study. J. Pediatr. 2004, 144, 614–619.

- Butler, M.G.; Haber, L.; Mernaugh, R.; Carlson, M.G.; Price, R.; Feurer, I.D. Decreased bone mineral density in Prader-Willi syndrome: Comparison with obese subjects. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2001, 103, 216–222.

- Höybye, C.; Hilding, A.; Jacobsson, H.; Thorén, M. Metabolic profile and body composition in adults with Prader-Willi syndrome and severe obesity. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002, 87, 3590–3597.

- Brunetti, G.; Grugni, G.; Piacente, L.; Delvecchio, M.; Ventura, A.; Giordano, P.; Grano, M.; D’Amato, G.; Laforgia, D.; Crinò, A.; et al. Analysis of Circulating Mediators of Bone Remodeling in Prader-Willi Syndrome. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2018, 102, 635–643.

- Van Nieuwpoort, I.C.; Twisk, J.W.R.; Curfs, L.M.G.; Lips, P.; Drent, M.L. Body composition, adipokines, bone mineral density and bone remodeling markers in relation to IGF-1 levels in adults with Prader-Willi syndrome. Int. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2018, 2018, 1–10.

More

Information

Subjects:

Pathology

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

669

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

19 Jan 2022

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No