Cystic kidney diseases, hereditary or acquired, are characterized by fluid-filled cysts. This pathology affecting millions of people worldwide leads to progressive loss of renal function. The present study demonstrates that abnormal activation in the renal epithelium of Notch3, a membrane receptor normally regulating vascular development and reactivity, participates in the formation of renal cysts, and thus adds a new factor in the mechanism(s) of progression of these incurable diseases.

1. Introduction

Cystic kidney diseases are characterized by fluid-filled cysts, which compress the surrounding renal parenchyma and derogate renal function [1]. They occur due to genetic mutations or can be acquired over time in patients with chronic kidney disease. Formation of renal cysts can begin as early as during fetal development and progress to end-stage renal diseases during the midlife years of a patient [2]. Cystic kidney disease is characterized by ciliary dysfunction, epithelial hyperplasia lesions, basement membrane abnormalities, such as mislocalization of NaK-ATPase, and tubulointerstitial inflammation and fibrosis [1][2][3].

Notch3 is expressed by vascular smooth muscle cells and regulates vascular development and reactivity [4]. We have previously demonstrated that in pathologic conditions, Notch3 is ectopically expressed by injured cells and promotes renal disease [5][6][7]. In chronic and acute kidney injury models, kidney tubular epithelial cells expressed Notch3 de novo, which mediated tubular proliferation and pro-inflammatory responses. Activation of Notch3 signaling in renal epithelial cells dramatically deteriorated the cell phenotype after injury, while Notch3 inhibition rescued renal function and structure [7]. Clinical and experimental data suggest a role of Notch signaling in renal cystogenesis. Mutations in JAG-1 and Notch-2 cause Alagille syndrome (AGS). Affected children have a deficiency in intrahepatic bile ducts, facial and skeletal anomalies and renal manifestations. While renal dysplasia accounts for most of the renal manifestations, bilateral renal cysts have also been identified in patients with AGS [8].

2. Notch3 Is De Novo Expressed in Epithelial Cells in Renal Carcinoma and Polycystic Kidney Disease

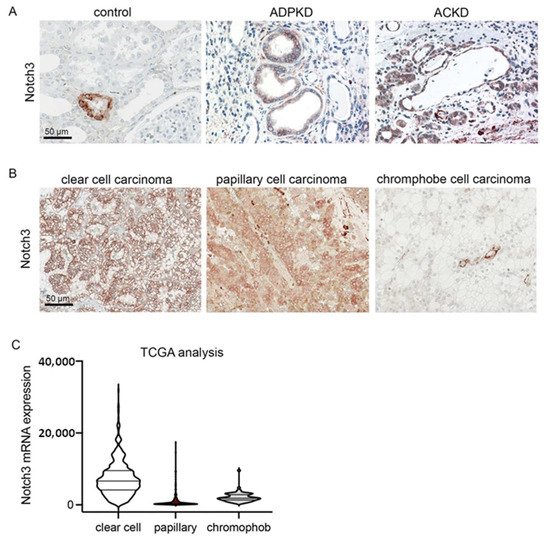

To examine whether Notch3 plays a role in polycystic disease in humans, we analyzed the expression of Notch3 in human biopsies from patients suffering from autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) and acquired cystic kidney disease (ACKD). Notch3 was highly upregulated in all patients with ADPKD (n = 5) and ACKD (n = 5). It was mainly expressed by tubular epithelial cells lining the cysts (Figure 1A). Tumor-distant nephrectomy tissue from tumor nephrectomies without another renal disease served as a control. Here, Notch3 was only expressed by α-smooth muscle cells in the vessels.

Figure 1. Notch3 expression is increased in polycystic kidney disease and renal cell carcinoma (RCC). Immunohistochemical staining for Notch3 in healthy control renal tissue and in tissue of patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) and acquired cystic kidney disease (ACKD) demonstrated a de novo expression of Notch3 in dilated tubules in ADPKD as well as ACKD (A). Immunohistochemical staining of biopsies from patients with different types of renal cell carcinoma also showed increased Notch3 expression (B). Reanalysis of publicly available TCGA confirmed increased Notch3 expression in renal cell carcinoma (C).

Further analysis of human biopsies from patients with different subtypes of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) showed that in all cases of RCCs, Notch3 was expressed by tubular epithelial cells (Figure 1B). Reanalysis of publicly available data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) revealed that NOTCH3 mRNA is expressed most strongly in clear cell renal cell carcinomas (Figure 1C).

3. Ectopic Notch3 Signaling Activation Compromises Renal Function and Increases Kidney Size

To examine the effect of Notch3 activation on the tubular epithelial cell phenotype, we used transgenic mice overexpressing the Notch3 intracellular domain (N3ICD) in tubular epithelial cells

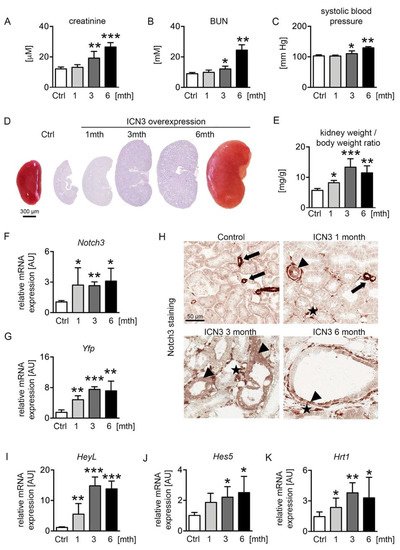

[7]. Two-month-old male mice were treated with doxycycline (dox) in the drinking water for ten days to activate N3ICD expression. Mice were sacrificed after one, three and six months of overexpression (abbreviated 1mth, 3mth and 6mth, respectively). We measured renal functional parameters, i.e., serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and systolic blood pressure. Serum creatinine and BUN levels were normal after the first month of doxycycline treatment but progressively increased at the later time points, demonstrating the significant deterioration of renal function after chronic N3ICD overexpression (

Figure 2A,B). Similarly, systolic blood pressure increased over time (

Figure 2C). Macroscopic and microscopic examination of N3ICD kidneys revealed a significant enlargement (

Figure 2D,E).

Figure 2. Notch3 overexpression alters renal function and structure. Two-month-old male N3ICD-overexpressing mice were treated for 10 days with doxycycline (dox) in the drinking water to activate N3ICD expression. Renal function was analyzed after one month (1mth, n = 5), three months (3mth, n = 6) and six months (6mth, n = 4) of overexpression and compared to control mice not treated with doxycycline (Ctrl, n = 5). Plasma creatinine (A), BUN (B) and systolic blood pressure (C) were significantly increased after chronic N3ICD overexpression in tubular epithelial cells. Afterwards, mice were sacrificed, and the kidney analyzed. Macro- and microscopic (PAS stain) analysis (D) and kidney per body weight ratio (E) showed a massive increase in kidney size after three months. N3ICD overexpression was confirmed by real-time PCR (F) and immunohistochemistry for Notch3 (H), and the gene expression of the Notch3 tag Yfp (yellow fluorescent protein) (G) and classical Notch target genes, i.e., HeyL (I), Hes5 (J) and Hrt1 (K). * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001, compared to control.

Notch3 expression was monitored with real-time PCR for Notch3 and Yfp (yellow fluorescent protein) expression, the latter tagging the N3ICD-overexpressing cassette (Figure 2F,G). Stable overexpression of N3ICD was found during the 6 months. Immunohistochemistry for N3ICD showed the expected vascular expression (Figure 2H arrows) in control mice. After doxycycline administration, N3ICD was expressed in tubules (Figure 2H arrowheads) and interstitial cells (Figure 2H stars). To verify that the transgene could activate the Notch signaling pathway, the expression of several downstream targets of Notch was evaluated. HeyL showed the most prominent increase from early on, and Hes5 and Hrt1 were also significantly upregulated (Figure 2I–K).

Collectively, renal epithelial activation of Notch3 signaling results in significant kidney enlargement and deterioration of renal function.

4. Notch3 Activation Generates Heterogeneous Cyst Formation

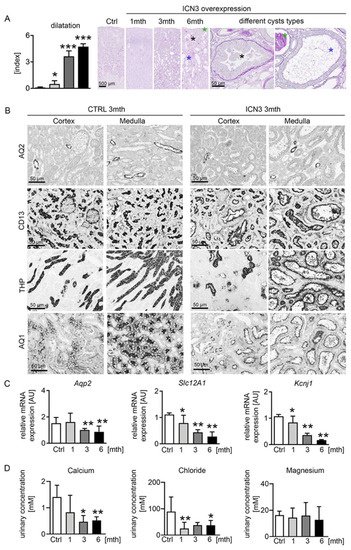

Histological examination demonstrated that morphologic changes started in the outer stripe of the outer medulla (OSOM). In control kidneys, the border between the cortex and medulla was clearly visible. Already one month after doxycycline treatment, tubules, especially in the OSOM, were bigger, hyperplastic and slightly dilated (Figure 3A). Over time, the tubular dilation increased towards cyst formation, and an increasing proportion of tubules in both the OSOM and renal cortex became affected (Figure 3A). The tubular cysts varied in size and appearance, identifying three main types of cyst phenotypes: (1) Cystic tubules with a monolayer of cuboid tubular epithelial cells that maintained their brush border. They occurred early, originally in the OSOM and only later in the cortex, and were hyperplastic, suggesting high proliferation (Figure 3A blue asterisk). (2) Cystic tubules filled with PAS-positive stained material and flattened tubular epithelial cells that had no brush border (Figure 3A green asterisk), occurring only at the latest time point. (3) Tubules showing hyperplastic lesions with multilayered, columnar epithelial cells with protrusions into the cystic lumen (Figure 3A black asterisk), also observed only at later stages. A common feature in all these cysts was a thickened basement membrane, especially in the hyperplastic cysts. The hyperplastic lesions showed no clear cells and no papillary growth. Additionally, no (micro)invasive growth was found, and no tumor formation was observed, at any time point. Additionally, macroscopically, no metastases were found in other organs. To identify the tubular segment involved in cyst formation, immunostaining experiments were performed with markers of the different tubular segments, i.e., aquaporin 2 (AQP2) for collecting ducts, CD13 and aquaporin 1 (AQP1) for proximal tubules and Tamm–Horsfall protein (THP) for the thick ascending limb (TAL). Proximal, distal and TAL cells appeared to equally contribute to the pool of dilated tubules and cysts, while collecting ducts retained their shape (Figure 3B). Next, we examined the expressions of several epithelial ion transports that are indicative of normal tubular function. Transcription levels of the medullary potassium channel ROMK (Kcnj1) and the multi-ion transporter NKCC2 (Slc12A1), localizing in the loop of Henle, decreased progressively starting from one month, leading to a decrease in the ion concentration in the urine (Figure 3C). The collecting duct water channel aquaporin 2 decreased after three months (Figure 3B,C).

Figure 3. Tubular phenotype after N3ICD overexpression. Scoring of tubular dilation in PAS staining revealed a significant increase and different cyst types (A). Highly dilated tubules with monolayer of cuboid tubular epithelial cells that maintained their brush border are marked with a blue asterisk; highly dilated tubules filled with PAS-positive stained material, consisting of flattened cells that had no brush border, are marked with a green asterisk; and tubules showing hyperplastic lesions with multilayered, columnar epithelial cells with protrusions into the cystic lumen are marked with a black asterisk. Immunohistochemistry for markers of different tubular segments, i.e., aquaporin 2 (AQP2) for collecting ducts, CD13 for proximal tubules, Tamm–Horsfall protein (THP) for the loop of Henle and distal tubules and aquaporin 1 (AQ1) for proximal tubules and descending loop of Henle, showed that proximal and distal tubules were largely affected three months after doxycyclin treatment (B). Real-time PCR for the collecting duct water channel aquaporin 2 showed a decrease after 3mth, whereas the potassium channel ROMK (Kcnj1) and the multi-ion transporter NKCC2 (Slc12A1), localizing in the loop of Henle, decreased progressively starting from 1mth (C). Urinary calcium and chloride concentrations were significantly decreased, whereas the magnesium concentration was not affected (D). * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001, compared to control.

Collectively, Notch3 overexpression induces distinct pathological cystic tubular alterations leading to a deterioration of tubular function with decreased ion channel expression, consistent with the development of cystic kidney disease.

5. Epithelial N3ICD Induces Severe Tubular Damage and Cell Dedifferentiation

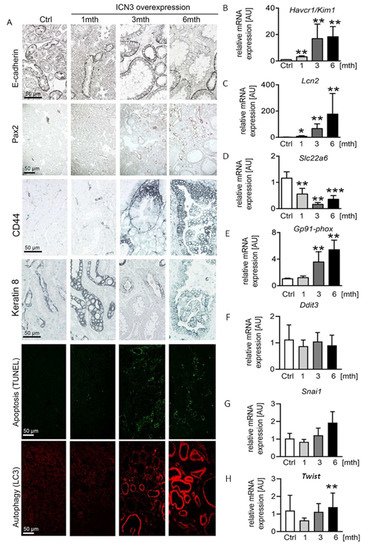

The water channels aquaporin 1 and 2 showed normal apical localization in the doxycycline-treated mice, suggesting that Notch3 activation did not influence cell polarity (Figure 3B). Additionally, E-cadherin expression showed a similar localization, but its expression was reduced over time in N3ICD mice (Figure 4A). Since decreased E-cadherin expression is a marker of tubular epithelial cell dedifferentiation [9][10], we examined the expression of Pax2, a transcription factor critical during renal development. It is mainly expressed in medullary tubular epithelial cells in the adult kidney [11] and in several renal cell carcinomas and is considered a marker of dedifferentiation [12]. The renal cortex of control mice was negative for Pax2. After one month of Notch3 activation, Pax2 was observed in a few tubular epithelial cells (Figure 4A). At three and six months, a significant number of cortical tubular epithelial cells expressed Pax2 (Figure 4A). Interestingly, strongly enlarged tubules were Pax2 negative, while less strongly dilated tubules were positive, indicating re-activation of Pax2 expression during the process of tubular enlargement.

Figure 4. Notch3 induces severe tubular epithelial cell stress and apoptosis. E-cadherin immunostaining decreased with time in response to Notch3 signaling activation (A). In addition, developmental transcription factor Pax2 was re-expressed in adult cortical tubular cells after N3ICD overexpression and increased with time (A), suggesting a dedifferentiation of the tubules. Apoptosis evaluation with TUNEL and autophagy evaluation with LC3 immunostaining revealed increased tubular cell death (A). Immunohistochemistry of tubular injury markers CD44 and keratin 8 (A), as well as real-time PCR for Havcr1/Kim1 (B) and Lcn2/Ngal (C) and for oxidative stress markers Slc22a6 (D) and GP91phox (E), revealed tubular injury already after one month. Ddit3 (CHOP) (F) and Snai1 (Snail) (G) were not changed due to N3ICD overexpression, whereas Twist significantly increased at 6 months (H). * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001, compared to control.

Next, we studied the phenotype of tubular epithelial cells using CD44 and Havcr1/Kim1, markers for tubular injury and regeneration. In healthy mice and mice one month after doxycycline treatment, CD44 was expressed only by some immune cells. At the later stages, CD44 was de novo expressed by tubular epithelial cells, increased over time and found in each cyst type independently of the cell shape (flattened, cuboid or columnar) (Figure 4A). In line with the increased CD44 expression, Havcr1/Kim1 mRNA expression increased significantly over time (Figure 4B).

To differentiate between tubular epithelial cell injury and regeneration, we measured stress and injury markers, and the expression of the cytoskeleton filament keratin 8, whose overabundance is a feature in ADPKD. Keratin 8 was only expressed by the collecting duct epithelium in healthy mice. After N3ICD activation, keratin 8 expression in collecting duct cells increased and was de novo expressed in dilated tubules (Figure 4A). Lcn2/NGAL, a widely used marker of tubular stress and injury, showed a similar expression pattern to Havcr1/Kim1, with a small increase at one month being followed by an important upregulation after three months (Figure 4C).

To assess whether the increased tubular injury is associated with autophagy and cell death, we evaluated apoptosis with the TUNEL assay and autophagy with LC3 staining. TUNEL revealed a very limited number of apoptotic epithelial cells one month after N3ICD induction that highly increased after three and six months (

Figure 4A). Apoptotic cells were usually absent from strongly enlarged tubules, possibly indicating an escape from cell regulatory mechanisms. LC3 staining revealed a strong increase after three months (

Figure 4A). By six months, all highly dilated tubules were positive for LC3 (

Figure 4A). To examine whether additional mechanisms contributed to epithelial stress and death, we measured the expression of markers of oxidative and endoplasmic reticulum stress (

Figure 4D–H). A decrease in OAT1 is considered as a marker of oxidative stress

[13]. Transcripts of organ anion transporter 1 (OAT1/

Slcc26) of the proximal tubules significantly decreased from one month (

Figure 4D). To verify that N3ICD overexpression induced oxidative stress, the expression of the NADPH subunit GP91 phox was quantified. Starting from three months of N3ICD, the expression of

Gp91-phox significantly increased, supporting the involvement of oxidative stress in this model (

Figure 4E). In contrast, gene expression of transcription factors involved in endoplasmic reticulum stress (

Chop/Ddit3) or epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and tumor progression (

Twist and

Snail) were not significantly altered (

Figure 4F–H).

Overall, Notch3 activation in adult tubular cells induces severe phenotypic alterations characterized by epithelial injury, dedifferentiation and cell death.

6. Notch3 Activation Leads to Hyperplasia and Disturbed Alignment of Cell Division

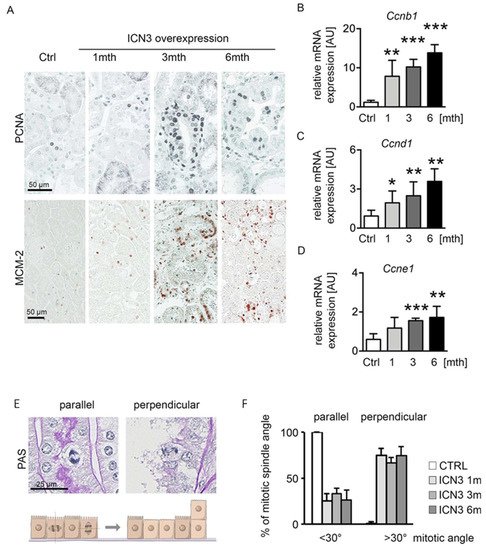

PKD is characterized by increased epithelial proliferation. To evaluate Notch3’s effect on proliferation and cyst formation, we measured proliferation using PCNA and MCM-2 (Figure 5A). A slight increase in proliferating cells one month after Notch3 activation was found, which peaked after three and slightly decreased after six months. To quantify proliferation at the different time points, cyclin expression was assessed with real-time PCR. Ccnb1, Ccnd1 and Ccnde1 showed identical expression patterns, with a time-dependent progressive increase (Figure 5B–D).

Figure 5. N3ICD overexpression induces proliferation. Immunohistochemistry for proliferation markers PCNA and MCM-2 (A) revealed increased tubular proliferation in response to N3ICD signaling. Quantification of cyclin b (Ccnb1; (B)), cyclin d (Ccnd1; (C)) and cyclin E (Ccne; (D)) mRNA expressions confirmed that proliferation increased in a time-dependent manner. In addition, Notch3 overexpression altered mitotic spindle orientation from planar to perpendicular (E,F). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001, compared to control.

The hyperplastic multilayered epithelium in several tubules suggests disorganized mitoses. Therefore, we quantified the mitotic spindle orientation and the occurrence of perpendicular proliferation (Figure 5E,F). Mitotic spindle angles <30° were defined as a mitotic spindle parallel to the basement membrane, while angles >30° were defined as a perpendicular orientation that can lead to cell division on top of each other (Figure 5E). Control mice showed a parallel mitotic spindle orientation, whereas N3ICD-overexpressing mice exhibited a reduced parallel and highly increased perpendicular orientation (Figure 5F).

These data suggest that overexpression of N3ICD produces proliferation with a disoriented mitotic spindle.

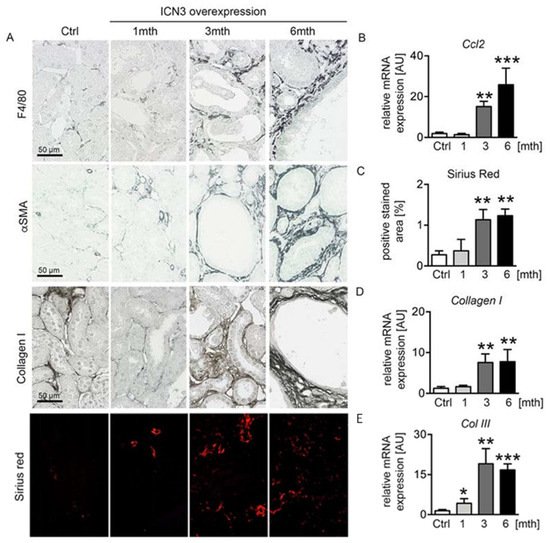

7. Epithelial N3ICD Resulted in Tubulointerstitial Inflammation and Fibrosis

Polycystic kidney disease is characterized by renal fibrosis, and the extent of fibrosis might be an important sign of PKD progression

[14]. We have previously reported that epithelial cells expressing Notch3 promote an inflammatory response and activate infiltrating macrophages

[5]. Chronic epithelial overexpression of N3ICD resulted in severe tubulointerstitial inflammation and fibrosis that progressed with time. Immunohistochemistry for the macrophage marker F4/80 showed a small number of infiltrating macrophages at one month that significantly increased at three months and six months, exhibiting peritubular localization (

Figure 6A). Real-time PCR for

Ccl2 confirmed the time-dependent evolution of inflammation (

Figure 6B). Accordingly, interstitial fibrosis assessed with immunohistochemistry for α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA) and collagen I, and Sirius red staining (

Figure 6A,C) progressed in parallel with inflammation. Real-time PCR for collagens I and III (

Figure 6D,E) confirmed the fibrotic response.

Figure 6. Notch3 overexpression results in severe tubulointerstitial inflammation and fibrosis. F4/80 immunostaining was used for evaluation of infiltrating macrophages, α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA) for fibroblast activation and collagen I and Sirius red for abnormal matrix deposition (A). Measurements of mRNA expressions of Ccl2 (B), Col I (D) and Col III (E) and quantification of Sirius red staining (C) confirmed increased inflammation and fibrosis in mice overexpressing N3ICD in a time-dependent manner. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001, compared to control mice.

8. Conclusion

We studied Notch3 expression in genetic autosomal dominant PKD (ADPKD) or acquired cystic kidney disease (ACKD) and in various types of renal tumors. Our first main finding was a significant up-regulation of Notch3 in epithelial cells of all PKD cases and renal cell carcinomas. To establish a relation between Notch3 signaling and disease progression, we overexpressed N3ICD in renal epithelial cells in vivo and monitored epithelial phenotype. Our second main finding was that the over-expression of the active intracellular domain of Notch3 (N3ICD) in tubular epithelial cells resulted in cystic kidney disease and pre-neoplastic lesions. We found that Notch3 signaling is part of the molecular program that regulates cell proliferation and restricts the orientation of epithelial cell division relative to the tubular basement membrane. Our study proposes Notch3 as a new and important player in progression of human tubular epithelium-originated diseases.