| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Carlos A Niño | + 8621 word(s) | 8621 | 2022-01-10 09:22:43 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | -2872 word(s) | 5749 | 2022-01-17 10:14:51 | | |

Video Upload Options

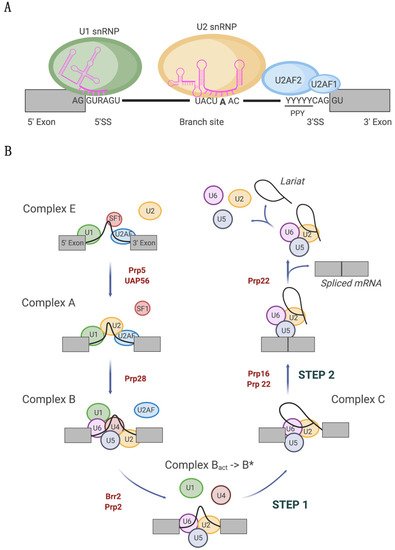

Splicing alterations have been widely documented in tumors where the proliferation and dissemination of cancer cells is supported by the expression of aberrant isoform variants. Splicing is catalyzed by the spliceosome, a ribonucleoprotein complex that orchestrates the complex process of intron removal and exon ligation. In recent years, recurrent hotspot mutations in the spliceosome components U1 snRNA, SF3B1, and U2AF1 have been identified across different tumor types. Such mutations in principle are highly detrimental for cells as all three spliceosome components are crucial for accurate splice site selection: the U1 snRNA is essential for 3′ splice site recognition, and SF3B1 and U2AF1 are important for 5′ splice site selection. Nonetheless, they appear to be selected to promote specific types of cancers.

1. Introduction

2. Tumor-Associated U1 snRNA Mutations Give Rise to Aberrant 5′ Splice Site Recognition

2.1. Molecular Basis of Altered Splicing Mediated by the U1 snRNA 3A > C/G Mutant

2.2. Oncogenic Roles of Mutant U1 snRNA 3A > C/G

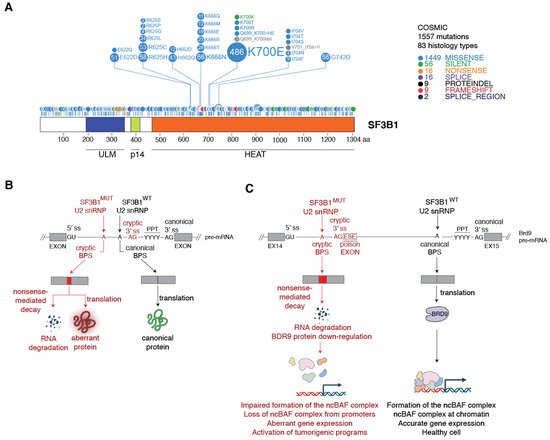

3. Spliceosomes Containing Mutant SF3B1 Promote Tumorigenesis through the Use of Cryptic 3′ Splice Sites

3.1. Molecular Basis of Cryptic 3′ Splice Site Usage by SF3B1MUT Spliceosomes

3.2. Mechanism of SF3B1MUT-Driven Tumorigenesis

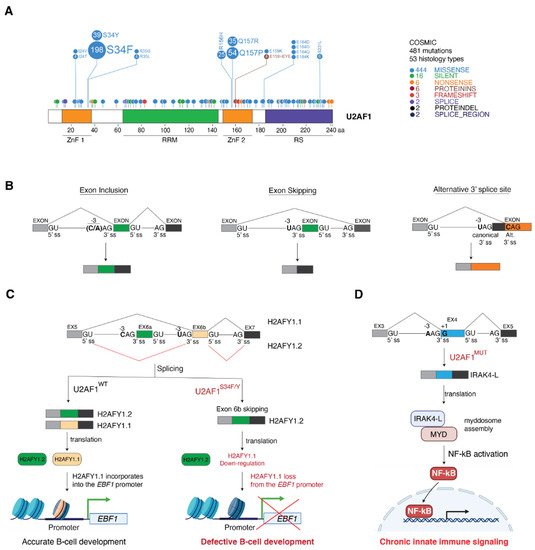

4. Cancer-Associated U2AF1 Mutations Influence U2AF1 3′ Splice Site Recognition and Splicing Outcome

4.1. Molecular Basis of Altered 3′ Splice Site Recognition by Mutant U2AF1

4.2. Consequences of U2AF1 Mutations on Tumorigenesis

5. Conclusions and Outlook

References

- Will, C.L.; Luhrmann, R. Spliceosome structure and function. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3, a003707.

- Matera, A.G.; Wang, Z. A day in the life of the spliceosome. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 108–121.

- Kastner, B.; Will, C.L.; Stark, H.; Luhrmann, R. Structural Insights into Nuclear pre-mRNA Splicing in Higher Eukaryotes. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2019, 11, a032417.

- Berglund, J.A.; Chua, K.; Abovich, N.; Reed, R.; Rosbash, M. The splicing factor BBP interacts specifically with the pre-mRNA branchpoint sequence UACUAAC. Cell 1997, 89, 781–787.

- Ruskin, B.; Zamore, P.D.; Green, M.R. A factor, U2AF, is required for U2 snRNP binding and splicing complex assembly. Cell 1988, 52, 207–219.

- Zamore, P.D.; Green, M.R. Identification, purification, and biochemical characterization of U2 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein auxiliary factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 9243–9247.

- Gozani, O.; Potashkin, J.; Reed, R. A potential role for U2AF-SAP 155 interactions in recruiting U2 snRNP to the branch site. Mol. Cell Biol. 1998, 18, 4752–4760.

- Schellenberg, M.J.; Edwards, R.A.; Ritchie, D.B.; Kent, O.A.; Golas, M.M.; Stark, H.; Luhrmann, R.; Glover, J.N.; MacMillan, A.M. Crystal structure of a core spliceosomal protein interface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 1266–1271.

- Kahles, A.; Lehmann, K.V.; Toussaint, N.C.; Huser, M.; Stark, S.G.; Sachsenberg, T.; Stegle, O.; Kohlbacher, O.; Sander, C.; The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive Analysis of Alternative Splicing across Tumors from 8705 Patients. Cancer Cell 2018, 34, 211–224.e216.

- Jayasinghe, R.G.; Cao, S.; Gao, Q.; Wendl, M.C.; Vo, N.S.; Reynolds, S.M.; Zhao, Y.; Climente-Gonzalez, H.; Chai, S.; Wang, F.; et al. Systematic Analysis of Splice-Site-Creating Mutations in Cancer. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 270–281.e273.

- Group, P.T.C.; Calabrese, C.; Davidson, N.R.; Demircioglu, D.; Fonseca, N.A.; He, Y.; Kahles, A.; Lehmann, K.V.; Liu, F.; Shiraishi, Y.; et al. Genomic basis for RNA alterations in cancer. Nature 2020, 578, 129–136.

- Paronetto, M.P.; Passacantilli, I.; Sette, C. Alternative splicing and cell survival: From tissue homeostasis to disease. Cell Death Differ. 2016, 23, 1919–1929.

- Di Matteo, A.; Belloni, E.; Pradella, D.; Cappelletto, A.; Volf, N.; Zacchigna, S.; Ghigna, C. Alternative splicing in endothelial cells: Novel therapeutic opportunities in cancer angiogenesis. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 39, 275.

- Mitra, M.; Lee, H.N.; Coller, H.A. Splicing Busts a Move: Isoform Switching Regulates Migration. Trends Cell Biol. 2020, 30, 74–85.

- Obeng, E.A.; Chappell, R.J.; Seiler, M.; Chen, M.C.; Campagna, D.R.; Schmidt, P.J.; Schneider, R.K.; Lord, A.M.; Wang, L.; Gambe, R.G.; et al. Physiologic Expression of Sf3b1(K700E) Causes Impaired Erythropoiesis, Aberrant Splicing, and Sensitivity to Therapeutic Spliceosome Modulation. Cancer Cell 2016, 30, 404–417.

- Shirai, C.L.; Ley, J.N.; White, B.S.; Kim, S.; Tibbitts, J.; Shao, J.; Ndonwi, M.; Wadugu, B.; Duncavage, E.J.; Okeyo-Owuor, T.; et al. Mutant U2AF1 Expression Alters Hematopoiesis and Pre-mRNA Splicing in vivo. Cancer Cell 2015, 27, 631–643.

- Inoue, D.; Chew, G.L.; Liu, B.; Michel, B.C.; Pangallo, J.; D’Avino, A.R.; Hitchman, T.; North, K.; Lee, S.C.; Bitner, L.; et al. Spliceosomal disruption of the non-canonical BAF complex in cancer. Nature 2019, 574, 432–436.

- Shuai, S.; Suzuki, H.; Diaz-Navarro, A.; Nadeu, F.; Kumar, S.A.; Gutierrez-Fernandez, A.; Delgado, J.; Pinyol, M.; Lopez-Otin, C.; Puente, X.S.; et al. The U1 spliceosomal RNA is recurrently mutated in multiple cancers. Nature 2019, 574, 712–716.

- Suzuki, H.; Kumar, S.A.; Shuai, S.; Diaz-Navarro, A.; Gutierrez-Fernandez, A.; De Antonellis, P.; Cavalli, F.M.G.; Juraschka, K.; Farooq, H.; Shibahara, I.; et al. Recurrent noncoding U1 snRNA mutations drive cryptic splicing in SHH medulloblastoma. Nature 2019, 574, 707–711.

- Kim, S.P.; Srivatsan, S.N.; Chavez, M.; Shirai, C.L.; White, B.S.; Ahmed, T.; Alberti, M.O.; Shao, J.; Nunley, R.; White, L.S.; et al. Mutant U2AF1-induced alternative splicing of H2afy (macroH2A1) regulates B-lymphopoiesis in mice. Cell Rep. 2021, 36, 109626.

- Zhuang, Y.; Weiner, A.M. A compensatory base change in U1 snRNA suppresses a 5′ splice site mutation. Cell 1986, 46, 827–835.

- Kondo, Y.; Oubridge, C.; van Roon, A.M.; Nagai, K. Crystal structure of human U1 snRNP, a small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle, reveals the mechanism of 5′ splice site recognition. eLife 2015, 4, e04986.

- Northcott, P.A.; Jones, D.T.; Kool, M.; Robinson, G.W.; Gilbertson, R.J.; Cho, Y.J.; Pomeroy, S.L.; Korshunov, A.; Lichter, P.; Taylor, M.D.; et al. Medulloblastomics: The end of the beginning. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 818–834.

- Seiler, M.; Peng, S.; Agrawal, A.A.; Palacino, J.; Teng, T.; Zhu, P.; Smith, P.G.; The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Somatic Mutational Landscape of Splicing Factor Genes and Their Functional Consequences across 33 Cancer Types. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 282–296.e284.

- Yoshida, K.; Sanada, M.; Shiraishi, Y.; Nowak, D.; Nagata, Y.; Yamamoto, R.; Sato, Y.; Sato-Otsubo, A.; Kon, A.; Nagasaki, M.; et al. Frequent pathway mutations of splicing machinery in myelodysplasia. Nature 2011, 478, 64–69.

- Wang, L.; Lawrence, M.S.; Wan, Y.; Stojanov, P.; Sougnez, C.; Stevenson, K.; Werner, L.; Sivachenko, A.; DeLuca, D.S.; Zhang, L.; et al. SF3B1 and other novel cancer genes in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 2497–2506.

- Landau, D.A.; Carter, S.L.; Stojanov, P.; McKenna, A.; Stevenson, K.; Lawrence, M.S.; Sougnez, C.; Stewart, C.; Sivachenko, A.; Wang, L.; et al. Evolution and impact of subclonal mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cell 2013, 152, 714–726.

- Harbour, J.W.; Roberson, E.D.; Anbunathan, H.; Onken, M.D.; Worley, L.A.; Bowcock, A.M. Recurrent mutations at codon 625 of the splicing factor SF3B1 in uveal melanoma. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 133–135.

- Malcovati, L.; Karimi, M.; Papaemmanuil, E.; Ambaglio, I.; Jadersten, M.; Jansson, M.; Elena, C.; Galli, A.; Walldin, G.; Della Porta, M.G.; et al. SF3B1 mutation identifies a distinct subset of myelodysplastic syndrome with ring sideroblasts. Blood 2015, 126, 233–241.

- Oscier, D.G.; Rose-Zerilli, M.J.; Winkelmann, N.; Gonzalez de Castro, D.; Gomez, B.; Forster, J.; Parker, H.; Parker, A.; Gardiner, A.; Collins, A.; et al. The clinical significance of NOTCH1 and SF3B1 mutations in the UK LRF CLL4 trial. Blood 2013, 121, 468–475.

- Landau, D.A.; Tausch, E.; Taylor-Weiner, A.N.; Stewart, C.; Reiter, J.G.; Bahlo, J.; Kluth, S.; Bozic, I.; Lawrence, M.; Bottcher, S.; et al. Mutations driving CLL and their evolution in progression and relapse. Nature 2015, 526, 525–530.

- Fu, X.; Tian, M.; Gu, J.; Cheng, T.; Ma, D.; Feng, L.; Xin, X. SF3B1 mutation is a poor prognostic indicator in luminal B and progesterone receptor-negative breast cancer patients. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 115018–115027.

- Spadaccini, R.; Reidt, U.; Dybkov, O.; Will, C.; Frank, R.; Stier, G.; Corsini, L.; Wahl, M.C.; Luhrmann, R.; Sattler, M. Biochemical and NMR analyses of an SF3b155-p14-U2AF-RNA interaction network involved in branch point definition during pre-mRNA splicing. RNA 2006, 12, 410–425.

- DeBoever, C.; Ghia, E.M.; Shepard, P.J.; Rassenti, L.; Barrett, C.L.; Jepsen, K.; Jamieson, C.H.; Carson, D.; Kipps, T.J.; Frazer, K.A. Transcriptome sequencing reveals potential mechanism of cryptic 3′ splice site selection in SF3B1-mutated cancers. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2015, 11, e1004105.

- Darman, R.B.; Seiler, M.; Agrawal, A.A.; Lim, K.H.; Peng, S.; Aird, D.; Bailey, S.L.; Bhavsar, E.B.; Chan, B.; Colla, S.; et al. Cancer-Associated SF3B1 Hotspot Mutations Induce Cryptic 3′ Splice Site Selection through Use of a Different Branch Point. Cell Rep. 2015, 13, 1033–1045.

- Alsafadi, S.; Houy, A.; Battistella, A.; Popova, T.; Wassef, M.; Henry, E.; Tirode, F.; Constantinou, A.; Piperno-Neumann, S.; Roman-Roman, S.; et al. Cancer-associated SF3B1 mutations affect alternative splicing by promoting alternative branchpoint usage. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10615.

- Cretu, C.; Schmitzova, J.; Ponce-Salvatierra, A.; Dybkov, O.; De Laurentiis, E.I.; Sharma, K.; Will, C.L.; Urlaub, H.; Luhrmann, R.; Pena, V. Molecular Architecture of SF3b and Structural Consequences of Its Cancer-Related Mutations. Mol. Cell 2016, 64, 307–319.

- Zhang, J.; Ali, A.M.; Lieu, Y.K.; Liu, Z.; Gao, J.; Rabadan, R.; Raza, A.; Mukherjee, S.; Manley, J.L. Disease-Causing Mutations in SF3B1 Alter Splicing by Disrupting Interaction with SUGP1. Mol. Cell 2019, 76, 82–95.e87.

- Bohnsack, K.E.; Ficner, R.; Bohnsack, M.T.; Jonas, S. Regulation of DEAH-box RNA helicases by G-patch proteins. Biol. Chem. 2021, 402, 561–579.

- Stilgenbauer, S.; Schnaiter, A.; Paschka, P.; Zenz, T.; Rossi, M.; Dohner, K.; Buhler, A.; Bottcher, S.; Ritgen, M.; Kneba, M.; et al. Gene mutations and treatment outcome in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Results from the CLL8 trial. Blood 2014, 123, 3247–3254.

- Wang, L.; Brooks, A.N.; Fan, J.; Wan, Y.; Gambe, R.; Li, S.; Hergert, S.; Yin, S.; Freeman, S.S.; Levin, J.Z.; et al. Transcriptomic Characterization of SF3B1 Mutation Reveals Its Pleiotropic Effects in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Cancer Cell 2016, 30, 750–763.

- Puente, X.S.; Pinyol, M.; Quesada, V.; Conde, L.; Ordonez, G.R.; Villamor, N.; Escaramis, G.; Jares, P.; Bea, S.; Gonzalez-Diaz, M.; et al. Whole-genome sequencing identifies recurrent mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nature 2011, 475, 101–105.

- Te Raa, G.D.; Derks, I.A.; Navrkalova, V.; Skowronska, A.; Moerland, P.D.; van Laar, J.; Oldreive, C.; Monsuur, H.; Trbusek, M.; Malcikova, J.; et al. The impact of SF3B1 mutations in CLL on the DNA-damage response. Leukemia 2015, 29, 1133–1142.

- Graubert, T.A.; Shen, D.; Ding, L.; Okeyo-Owuor, T.; Lunn, C.L.; Shao, J.; Krysiak, K.; Harris, C.C.; Koboldt, D.C.; Larson, D.E.; et al. Recurrent mutations in the U2AF1 splicing factor in myelodysplastic syndromes. Nat. Genet. 2011, 44, 53–57.

- Makishima, H.; Visconte, V.; Sakaguchi, H.; Jankowska, A.M.; Abu Kar, S.; Jerez, A.; Przychodzen, B.; Bupathi, M.; Guinta, K.; Afable, M.G.; et al. Mutations in the spliceosome machinery, a novel and ubiquitous pathway in leukemogenesis. Blood 2012, 119, 3203–3210.

- Saygin, C.; Hirsch, C.; Przychodzen, B.; Sekeres, M.A.; Hamilton, B.K.; Kalaycio, M.; Carraway, H.E.; Gerds, A.T.; Mukherjee, S.; Nazha, A.; et al. Mutations in DNMT3A, U2AF1, and EZH2 identify intermediate-risk acute myeloid leukemia patients with poor outcome after CR1. Blood Cancer J. 2018, 8, 4.

- Imielinski, M.; Berger, A.H.; Hammerman, P.S.; Hernandez, B.; Pugh, T.J.; Hodis, E.; Cho, J.; Suh, J.; Capelletti, M.; Sivachenko, A.; et al. Mapping the hallmarks of lung adenocarcinoma with massively parallel sequencing. Cell 2012, 150, 1107–1120.

- Wu, S.; Romfo, C.M.; Nilsen, T.W.; Green, M.R. Functional recognition of the 3′ splice site AG by the splicing factor U2AF35. Nature 1999, 402, 832–835.

- Merendino, L.; Guth, S.; Bilbao, D.; Martinez, C.; Valcarcel, J. Inhibition of msl-2 splicing by Sex-lethal reveals interaction between U2AF35 and the 3′ splice site AG. Nature 1999, 402, 838–841.

- Zorio, D.A.; Blumenthal, T. Both subunits of U2AF recognize the 3′ splice site in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 1999, 402, 835–838.

- Przychodzen, B.; Jerez, A.; Guinta, K.; Sekeres, M.A.; Padgett, R.; Maciejewski, J.P.; Makishima, H. Patterns of missplicing due to somatic U2AF1 mutations in myeloid neoplasms. Blood 2013, 122, 999–1006.

- Brooks, A.N.; Choi, P.S.; de Waal, L.; Sharifnia, T.; Imielinski, M.; Saksena, G.; Pedamallu, C.S.; Sivachenko, A.; Rosenberg, M.; Chmielecki, J.; et al. A pan-cancer analysis of transcriptome changes associated with somatic mutations in U2AF1 reveals commonly altered splicing events. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87361.

- Yoshida, H.; Park, S.Y.; Sakashita, G.; Nariai, Y.; Kuwasako, K.; Muto, Y.; Urano, T.; Obayashi, E. Elucidation of the aberrant 3′ splice site selection by cancer-associated mutations on the U2AF1. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4744.

- Ilagan, J.O.; Ramakrishnan, A.; Hayes, B.; Murphy, M.E.; Zebari, A.S.; Bradley, P.; Bradley, R.K. U2AF1 mutations alter splice site recognition in hematological malignancies. Genome Res. 2015, 25, 14–26.

- Okeyo-Owuor, T.; White, B.S.; Chatrikhi, R.; Mohan, D.R.; Kim, S.; Griffith, M.; Ding, L.; Ketkar-Kulkarni, S.; Hundal, J.; Laird, K.M.; et al. U2AF1 mutations alter sequence specificity of pre-mRNA binding and splicing. Leukemia 2015, 29, 909–917.

- Esfahani, M.S.; Lee, L.J.; Jeon, Y.J.; Flynn, R.A.; Stehr, H.; Hui, A.B.; Ishisoko, N.; Kildebeck, E.; Newman, A.M.; Bratman, S.V.; et al. Functional significance of U2AF1 S34F mutations in lung adenocarcinomas. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 5712.

- Park, S.M.; Ou, J.; Chamberlain, L.; Simone, T.M.; Yang, H.; Virbasius, C.M.; Ali, A.M.; Zhu, L.J.; Mukherjee, S.; Raza, A.; et al. U2AF35(S34F) Promotes Transformation by Directing Aberrant ATG7 Pre-mRNA 3′ End Formation. Mol. Cell 2016, 62, 479–490.

- Palangat, M.; Anastasakis, D.G.; Fei, D.L.; Lindblad, K.E.; Bradley, R.; Hourigan, C.S.; Hafner, M.; Larson, D.R. The splicing factor U2AF1 contributes to cancer progression through a noncanonical role in translation regulation. Genes Dev. 2019, 33, 482–497.

- Smith, M.A.; Choudhary, G.S.; Pellagatti, A.; Choi, K.; Bolanos, L.C.; Bhagat, T.D.; Gordon-Mitchell, S.; Von Ahrens, D.; Pradhan, K.; Steeples, V.; et al. U2AF1 mutations induce oncogenic IRAK4 isoforms and activate innate immune pathways in myeloid malignancies. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 640–650.

- Gamble, M.J.; Frizzell, K.M.; Yang, C.; Krishnakumar, R.; Kraus, W.L. The histone variant macroH2A1 marks repressed autosomal chromatin, but protects a subset of its target genes from silencing. Genes Dev. 2010, 24, 21–32.

- Zarrin, A.A.; Bao, K.; Lupardus, P.; Vucic, D. Kinase inhibition in autoimmunity and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 39–63.

- Zhou, Q.; Derti, A.; Ruddy, D.; Rakiec, D.; Kao, I.; Lira, M.; Gibaja, V.; Chan, H.; Yang, Y.; Min, J.; et al. A chemical genetics approach for the functional assessment of novel cancer genes. Cancer Res. 2015, 75, 1949–1958.

- Wadugu, B.A.; Nonavinkere Srivatsan, S.; Heard, A.; Alberti, M.O.; Ndonwi, M.; Liu, J.; Grieb, S.; Bradley, J.; Shao, J.; Ahmed, T.; et al. U2af1 is a haplo-essential gene required for hematopoietic cancer cell survival in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e141401.

- Eskens, F.A.; Ramos, F.J.; Burger, H.; O’Brien, J.P.; Piera, A.; de Jonge, M.J.; Mizui, Y.; Wiemer, E.A.; Carreras, M.J.; Baselga, J.; et al. Phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of the first-in-class spliceosome inhibitor E7107 in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 6296–6304.

- Bennett, C.F. Therapeutic Antisense Oligonucleotides Are Coming of Age. Annu. Rev. Med. 2019, 70, 307–321.

- Meylemans, A.; De Bleecker, J. Current evidence for treatment with nusinersen for spinal muscular atrophy: A systematic review. Acta Neurol. Belg. 2019, 119, 523–533.